Introduction

Although blood donation is generally a safe

procedure, undesirable reactions can occur during or after the

collection of whole blood or blood components. The most common

adverse event is a vasovagal reaction (VVR; or vasovagal syncope).

VVRs are considered to be triggered by various physical (e.g.,

standing up after losing 500 ml blood) and psychological stimuli

(e.g., pain, stress and fear) (1).

During a VVR, there is a decrease in the arterial blood pressure

and cerebral perfusion of the donor, which reduces the blood flow

to the brain (2). The highest

frequency of VVRs in whole blood donors occurs during needle

removal and when leaving the donation chair (3). A small proportion (9-12%) of reported

VVRs occurs after the donor leaves the center. However, the number

of off-site reactions is often underestimated due to underreporting

by donors (4). The symptoms of VVRs

include general weakness, dizziness, pallor, sweating, anxiety and

nausea; additionally, some donors may experience more severe

symptoms, such as a transient loss of consciousness (syncope),

convulsions, or incontinence (5).

Fainting and falling can result in accidental injuries. VVRs also

prevent individuals from donating again, decreasing the likelihood

of repeat donations by >50% (6,7).

VVRs affect donor safety and future donation

behavior. They also negatively affect donor waiting times,

appointment management and the number of completed blood

collections (7). Therefore, risk

factors for VVR need to be identified, and preventive policies need

to be developed. The present study aimed to investigate the

frequency and causes of VVR in whole blood donors at the

Transfusion Center, Faculty of Medicine, Necmettin Erbakan

University.

Subjects and methods

Donor information

A total of 742 donors who applied for whole blood

donation at the Necmettin Erbakan University Transfusion Center

(Konya, Turkey) were included in the study. The present study was

conducted between September and October, 2024. Donor eligibility

was evaluated according to the National Blood and Blood Component

Preparation, Use, and Quality Assurance Guide (8). All donors were provided with

information about the donation process prior to the donation.

Potential complications were explained. At this stage, those who

decided to withdraw from blood donation were not pressured to

continue. Following the donation, donors were taken to the rest

area where they were served fruit juice and encouraged to sit and

rest for 15 min. In cases of VVR, necessary interventions were

performed by the doctor. To assess the health status of the donors

and determine their eligibility for blood donation, blood pressure,

body temperature, and pulse rate were measured prior to the

donation.

An average of 450±45 cc of whole blood was collected

from the donors. Donor age, sex, comorbidities, fasting status,

time since last meal, blood donation history, leukocyte count,

hemoglobin level and platelet count were recorded. The frequency

and timing of VVRs were determined, and the association between

VVRs and the donor characteristics was analyzed. The present study

was approved by the Necmettin Erbakan University, Ethics Committee

for Non-Pharmaceutical and Non-Medical Device Research (2024-5381).

Written consent was obtained from the participants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

IBM program, version 23.0 (IBM Corp.). The distribution

characteristics of continuous variables were evaluated using the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics for normally

distributed data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation,

while non-normally distributed data are presented as the median

(range). Group comparisons for continuous variables were conducted

using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are expressed

as percentages (%) and compared using the Fisher's test. Values of

P<0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

A total of 742 blood donors were evaluated. The

median age of the donors was 36 years (range, 18-67 years), with 69

(9.8%) female and 673 (90.2%) male donors. The median age of the

donors was similar between the male and female donors (35 years vs.

36 years).

VVR was detected in 37 (4.9%) donors. A total of 7

out of 62 females (10.1%) and 30 out of 643 males (4.45%) developed

VVR, with no significant difference. The median age of the donors

who experienced VVR was significantly lower than that of those who

did not (P=0.04). Of note, 16% of the donors (119 individuals) were

first-time donors. VVRs developed in 10% (12 individuals) of the

first-time donors. First-time blood donors had a higher incidence

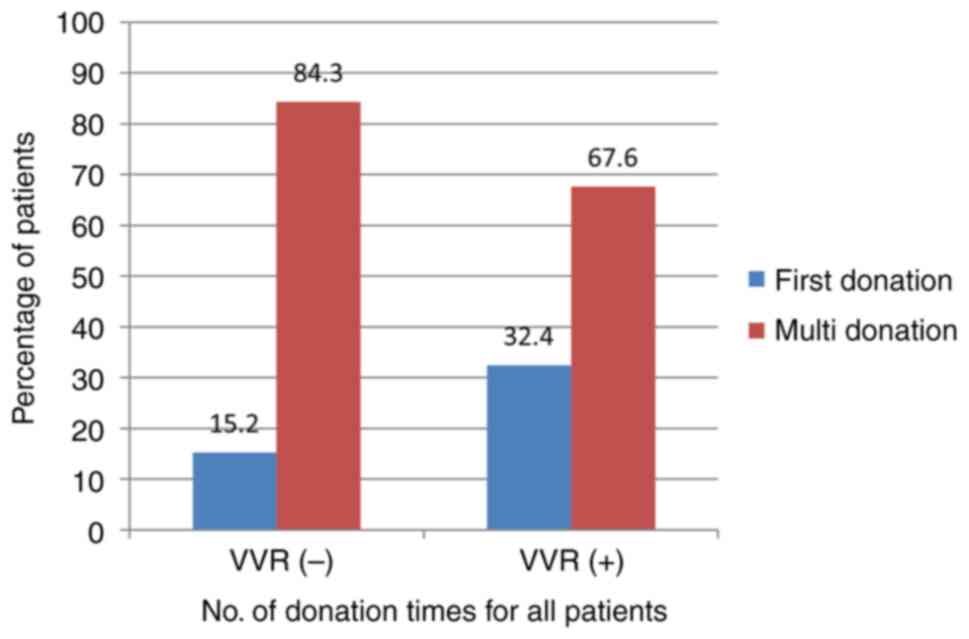

of VVR (32.4% vs. 15.2%, P=0.010) (Fig.

1). The median blood donation rate for donors who experienced

VVRs was 2, compared to 4 for those who did not, and this

difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table I). No significant effects of fasting

status, sex, comorbidities, leukocyte count, hemoglobin,

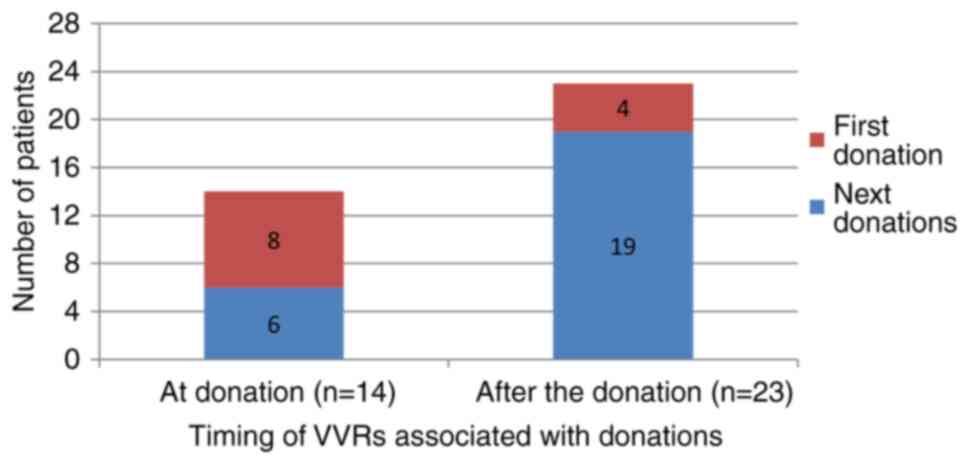

hematocrit, or platelet count on VVRs were found (Table I). As regards the timing of VVRs,

among the 37 donors who experienced VVRs, 14 (37.8%) had it during

the donation, and 23 (62.2%) after the donation. First-time donors

had a higher rate of VVR during the donation (57.1% vs. 17.4%,

P=0.027) (Table I and Fig. 2).

| Table IEpidemiological and laboratory

comparison of the donors with and without VVRs. |

Table I

Epidemiological and laboratory

comparison of the donors with and without VVRs.

| Parameter | VVR (-) (n:705) | VVR (+) (n:37) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) | | | 0.072a |

|

Female | 62 (8.8) | 7 (18.9) | |

|

Male | 643 (91.2) | 30 (81.1) | |

| Additional disease,

n (%) | | | NSa |

|

Yes | 18 (2.6) | 0 | |

|

No | 687 (97.4) | 37(100) | |

| Fasting status, n

(%) | | | NSa |

|

Yes | 11 (1,6) | 0 | |

|

No | 694 (98.4) | 37 | |

| Donation

history | | |

0.010a |

|

First-time | 107 (15.2) | 12 (32.4) | |

|

Repeat | 598 (84.8) | 25 (67.6) | |

| Age (median,

range) | 36 (18-67) | 30 (18-56) |

0.04b |

| Time since last

meal (h) | 2 (0.5-12) | 1 (0.5-4) | 1.29b |

| No. of blood

donations | 4 (0-80) | 2 (0-20) |

<0.001b |

| Leukocyte count

(mm3) | 7,745

(4,100-11,800) | 7,550

(5,400-12,500) | 0.611b |

| Hemoglobin

(g/dl) | 15.3 (12,4-18) | 15 (12.5-17.5) | 0.072b |

| Hematocrit (%) | 44.6

(36.1-52.1) | 43.6

(28.2-50.9) | 0.064b |

| Platelet count

(x103/µl) | 277.5

(112-475) | 294 (122-393) | 0.79b |

| No. of donation

times, n (%) | | | 0.010a |

|

First

donation | 107 (15.2) | 12 (32.4) | |

|

Multiple

donations | 598 (84.3) | 25 (67.6) | |

| The timing of

VVRsc, n (%) | | | 0.027a |

|

During the

donation (n=14) | | | |

|

First

donation | | | |

|

Multiple

donations | | 8 (57.1) | |

|

After the

donation (n=23) | | 6 (42.9) | |

|

First

donation | | | |

|

Multiple

donations | | 4 (17.4) | |

| | | 19 (82.6) | |

Discussion

In blood donation, moderate VVRs occur in 1.4 to 7%

of individuals, and severe VVRs occur in 0.1 to 0.5% of cases

(4,9-18).

The present study found a VVR rate of 4.9%, which is similar to

that observed in the literature. The hospitalization rate due to

blood donation complications has been reported as 1/198,000, with

two-thirds of these events associated with VVRs. Falls leading to

injuries have been found to be the most significant cause in female

donors (4). None of the donors in

the present study required hospitalization.

The following risk factors have been shown to be

associated with an increased risk of VVRs: The female sex (7,19,20), a

low body weight (21,22), a low estimated blood volume (9,20,23), a

younger age (7,9,19,23),

first-time donation (7,19,22,23), a

low resting blood pressure (21),

insufficient sleep prior to donation (24,25),

donation site (23) and a history of

symptoms during previous donations (26,27). The

frequency of VVRs has been found to be higher in first-time, young

and female donors (21,28,29).

Additionally, donors who experienced VVRs had a significantly lower

total blood donation count. This may be due to regular donations

from those who did not experience VVRs in previous donations, while

those who experienced VVRs tend to avoid further donations. Unlike

other studies, the female sex was not found to be a risk factor for

VVRs in the present study, possibly due to the smaller number of

female donors. The primary reason for the low number of female

donors is iron deficiency anemia, which develops in menstruating

women. Iron deficiency affects 29 to 58% of healthy females of

reproductive age, while the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia

ranges from 27 to 47% (30-32).

Another reason is the reluctance to select women who have had

pregnancies as donors in Turkey. The female donor rate and the

frequency of VVR occurrence among female donors in different

countries is presented in Table II.

The frequency of female donors varies greatly across countries.

Upon reviewing these studies, it appears that factors, such as the

level of development of the countries and religious beliefs play a

prominent role in influencing the rate of female donors. Similar to

these countries, in the authors' country, Turkey, the

socio-cultural situation may be another main reason for women

donating less in certain segments of society.

| Table IIIncidence of vasovagal reactions in

blood donation in different countries worldwide. |

Table II

Incidence of vasovagal reactions in

blood donation in different countries worldwide.

| Country (year of

publication) | Sample size | % of bood donation

in females | % of females

developing VVR | % of blood donation

in first donors | % of VVR improving

in first-time donors | Incidence of VVR

(%) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| USA (2008) | 422,231 | 57.9 | 1.86 | 24.6 | 2.75 | 1.43 | (9) |

| USA (2010) | 793,293 | 48 | 0.65 | 21 | 0.89 | 0.41 | (4) |

| Saudi Arabia

(2017) | 18,936 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 47 | 1.6 | 1.1 | (12) |

| Italy (2009) | 183,855 | 8.6 | | 19.5 | | 0.19 | (13) |

| India (2014) | 88,201 | 3.9 | | 35.8 | | 1.23 | (14) |

| Pakistan

(2016) | 41,579 | 0.2 | 0 | | | 1.03 | (15) |

| Germany (2015) | 928,411 | 47.8 | | 8.2 | 2.78 | 0.76 | (16) |

| Iran (2011) | 5,285 | 4.4 | 8.6 | 18 | 5.6 | 2 | (17) |

| Brazil (2012) | 724,861 | 30 | 3.39 | 31.5 | 4.28 | 2.2 | (18) |

| Turkey (2025) | 742 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 16 | 10 | 4.9 | Present study |

Setting weight limits for blood donation is critical

for protecting donors from adverse effects, particularly vasovagal

episodes and anemia. It has been shown that a low body weight and

low blood volume are independent predictors of VVRs (10,21).

Trouern-Trend et al (21)

demonstrated that a low body weight increases the risk of

developing VVRs. They demonstrated that VVRs developed in 4.6% of

individuals with a body weight <120 lb and in 0.4% of those with

a body weight >210 lb (21).

Another study found that body weight was a significant determinant

of the rate of vasovagal reactions in first-time blood donors

(22). In general, it is accepted

that the total volume of donated blood should not exceed 13% of the

blood volume of the donor. For example, a donor must weigh at least

45 kg to donate 350 ml (±10%) of blood, and at least 50 kg to

donate 450 ml (±10%) of blood (38).

There is no specific upper weight limit for blood donation. In

Turkey, the donor selection criteria require that the donor weighs

>50 kg (8).

Psychological stresses, such as pre-donation sleep

duration, a history of fainting epidodes, anxiety traits, a fear of

blood and injury, and a fear of needles have been associated with

VVRs (24,34-37).

In their study, Takanashi et al (24) compared the records of 4,924 Japanese

donors who experienced VVR with a control group of 43,948 donors

who did not experience any such complications which were related to

donation. As observed in their study, for both male and female

donors, factors such as being a first-time donor, having a

pre-donation pulse rate of ≥90 beats per minute, a diastolic blood

pressure ≤70 mmHg, <6 h of sleep (compared to >8 h of sleep),

not eating within the previous 4 h, and factors such as age, sex,

body mass index, pulse rate and systolic blood pressure were all

significantly associated with an increased risk of having VVRs

(24).

The underlying mechanisms of VVRs include the

orthostatic effects of hypovolemic static status (i.e., a decrease

in blood pressure when standing up following the donation) and

psychological stress related to the procedure (e.g., pain

associated with needle insertion or phlebotomy) (38). Due to the complexity of the

mechanisms involved, current prevention strategies target both the

physiological and psychological aspects of the reaction (39).

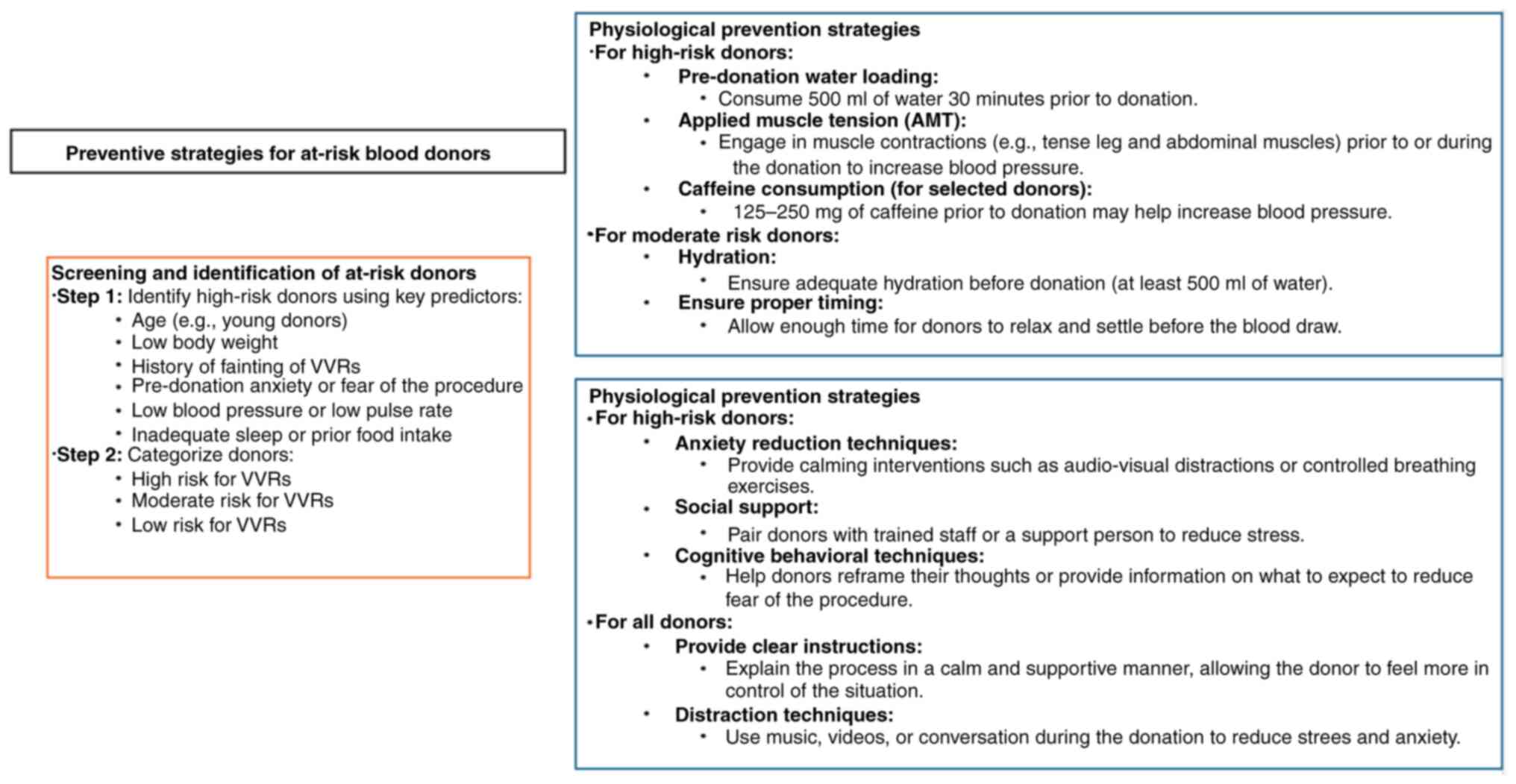

Various strategies have been proposed to prevent

VVRs. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends

pre-donation hydration and the application of active muscle tension

(AMT) to increase blood flow and blood pressure. The EU Domaine

Project supports pre-donation hydration and AMT, as well as

caffeine loading, distraction techniques, supportive care, and

educational materials (40-42).

Blood services worldwide have adopted various strategies to prevent

VVRs, with water loading and AMT being the most common (43,44).

Compared to the empirical literature focusing on

pre-donation hydration and AMT, only a limited number of studies

have addressed the psychological aspects of the donation and their

association with vasovagal symptoms. Studies evaluating

psychological methods primarily focus on reducing stress or anxiety

by providing distraction or social support during the procedure

(39). In a previous study, the

effectiveness of audiovisual distraction for first-time donors was

investigated by classifying individuals based on their coping

styles as monitoring (attending to the situation) or blunting

(distracting, denying, or reinterpreting the situation) (45). Donors with blunting coping styles who

were provided with a distracting environment reported significantly

lower self-reported vasovagal symptoms compared to participants in

the untreated control condition (45). Hanson and France (46) demonstrated that donors who were

accompanied by a trained research assistant for support had lower

VVR levels and were more willing to donate again compared to donors

who did not receive support.

VVRs can be minimized with simple precautions. First

and foremost, donor education is essential. Donors should be

advised to avoid coming on an empty stomach, refrain from smoking

before and after donation, avoid standing up immediately after

donation (and instead sit up first), and ensure adequate fluid

intake before and/or after donation. These measures will prevent

the majority of cases of VVRs. However, despite these precautions,

VVRs may still occur, particularly in first-time blood donors, due

to psychological stress. Donors who exhibit signs of psychological

stress should receive psychological support before proceeding with

blood donation. Therefore, blood donation centers should have

trained personnel capable of providing psychological support.

Another potential factor in reducing VVR is ensuring that the blood

donation environment is spacious, clean, well-ventilated, and

comfortable. Additionally, a friendly attitude from the staff,

effective communication, reassuring the donor, and good technical

skills are important factors in reducing VVR (Fig. 3).

A limitation of the present study is the lack of the

evaluation of body weight, blood pressure, body temperature, oxygen

saturation and psychological stress levels prior to donation. These

factors could provide valuable insight into the overall health and

well-being of donors, potentially affecting the donation process

and outcomes. In future studies on this topic, the inclusion of

these parameters would enhance the value of the research and offer

a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing

donation. Another limitation of the present study is the

significantly lower number of females compared to males. However,

this is not a choice of the authors, but rather a result of the

general tendency of females in Turkey to donate blood.

As a result, in the present study, the frequency of

VVRs was found to be 4.9%, and it was observed that VVRs developed

more frequently in younger individuals and first-time donors.

Although numerous intervention studies have evaluated the

effectiveness of physiological and psychological methods in

preventing VVRs and/or vasovagal symptoms, questions regarding the

efficacy of these techniques remain. A reasonable approach may be

to apply both physiological and psychological preventive methods to

young first-time donors to prevent them from experiencing VVRs.

This is due to the fact that those who experience VVRs during their

first blood donation tend to avoid donating again, which leads to a

decrease in the number of blood donors.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SD was a main contributor to the conception of the

study, as well as to the literature search for related studies. SD,

HD and ATe were involved in the literature review, in the writing

of the manuscript, and in the analysis and interpretation of the

patient data. ATü and ATo collected data. HD and Ate confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Necmettin

Erbakan University, Ethics Committee for Non-Pharmaceutical and

Non-Medical Device Research (2024-5381). Written consent was

obtained from the participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gilchrist PT and Ditto B: Sense of

impending doom: Inhibitory activity in waiting blood donors who

subsequently experience vasovagal symptoms. Biol Psychol.

104:28–34. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wieling W, Thijs RD, van Dijk N, Wilde

AAM, Benditt DG and van Dijk JG: Symptoms and signs of syncope: A

review of the link between physiology and clinical clues. Brain.

132:2630–2642. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tomasulo P, Bravo M and Kamel H: Time

course of vasovagal syncope with whole blood donation. ISBT Sci

Ser. 5:52–58. 2010.

|

|

4

|

Kamel H, Tomasulo P, Bravo M, Wiltbank T,

Cusick R, James RC and Custer B: Delayed adverse reactions to blood

donation. Transfusion (Paris). 50:556–565. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wiersum-Osselton JC, Marijt-van der Kreek

T, Brand A, Veldhuizen I, van der Bom JG and de Kort W: Risk

factors for complications in donors at first and repeat whole blood

donation: A cohort study with assessment of the impact on donor

return. Blood Transfus. 12 (Suppl 1):S28–S36. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Rader AW, France CR and Carlson B: Donor

retention as a function of donor reactions to whole-blood and

automated double red cell collections. Transfusion (Paris).

47:995–1001. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

France CR, Rader A and Carlson B: Donors

who react may not come back: Analysis of repeat donation as a

function of phlebotomist ratings of vasovagal reactions. Transfus

Apher Sci. 33:99–106. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

National Guide for Blood and Blood

Components Preparation, Usage and Quality Assurance. Republic of

Turkey, Ministry of Health, 2016. Available from: https://shgmkanhizmetleridb.saglik.gov.tr/TR,71523/ulusal-kan-ve-kan-bilesenleri-hazirlama-kullanim-ve-kalite-guvencesi-rehberi-2016.html.

|

|

9

|

Wiltbank TB, Giordano GF, Kamel H,

Tomasulo P and Custer B: Faint and prefaint reactions in

whole-blood donors: An analysis of predonation measurements and

their predictive value. Transfusion. 48:1799–1808. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lin JT, Ziegler DK, Lai C and Bayer W:

Convulsive syncope in blood donors. Ann Neurol. 11:525–528.

1982.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Newman BH: Blood donor complications after

whole-blood donation. Curr Opin Hematol. 11:339–345.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Almutairi H, Salam M, Alajlan A, Wani F,

Al-Shammari B and Al-Surimi K: Incidence, predictors and severity

of adverse events among whole blood donors. PLoS One.

12(e0179831)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Crocco I, Franchini M, Garozzo G, Gandini

AR, Gandini G, Bonomo P and Aprili G: Adverse reactions in blood

and apheresis donors: Experience from two Italian transfusion

centres. Blood Transfus. 7:35–38. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Philip J, Sarkar R and Jain N: A

single-centre study of vasovagal reaction in blood donors:

Influence of age, sex, donation status, weight, total blood volume

and volume of blood collected. Asian J Transfus Sci. 8:43–46.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sultan S, Baig MA, Irfan SM, Ahmed SI and

Hasan S: Adverse reactions in allogeneic blood donors: A tertiary

care experience from a developing country. Oman Med J. 31:124–128.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Burkhardt T, Dimanski B, Karl R, Sievert

U, Karl A, Hübler C, Tonn T, Sopvinik I, Ertl H and Moog R: Donor

vigilance data of a blood transfusion service: A multicenter

analysis. Transfus Apher Sci. 53:180–184. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Assarian Z, Haghighi BA, Javadi I, Fotouhi

A, Seighali F and Akbari N: Risk factors for vasovagal reactions

during blood donation. Sci J Iran Blood Transfus Organ. 7:221–226.

2011.

|

|

18

|

Gonçalez TT, Sabino EC, Schlumpf KS,

Wright DJ, Leao S, Sampaio D, Takecian PL, Proietti AB, Murphy E,

Busch M, et al: Vasovagal reactions in whole blood donors at three

REDS-II blood centers in Brazil. Transfusion. 52:1070–1078.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Eder AF, Hillyer CD, Dy BA, Notari EP IV

and Benjamin RJ: Adverse reactions to allogeneic whole blood

donation by 16- and 17-year-olds. JAMA. 299:2279–2286.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Goldman M, Osmond L, Yi QL, Cameron-Choi K

and O'Brien SF: Frequency and risk factors for donor reactions in

an anonymous blood donor survey. Transfusion. 53:1979–1984.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Trouern-Trend JJ, Cable RG, Badon SJ,

Newman BH and Popovsky MA: A case-controlled multicenter study of

vasovagal reactions in blood donors: Influence of sex, age,

donation status, weight, blood pressure, and pulse. Transfusion.

39:316–320. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Newman BH: Vasovagal reaction rates and

body weight: Findings in high- and low-risk populations.

Transfusion. 43:1084–1088. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bravo M, Kamel H, Custer B and Tomasulo P:

Factors associated with fainting-before, during and after whole

blood donation. Vox Sang. 101:303–312. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Takanashi M, Odajima T, Aota S, Sudoh M,

Yamaga Y, Ono Y, Yoshinaga K, Motoji T, Matsuzaki K, Satake M, et

al: Risk factor analysis of vasovagal reaction from blood donation.

Transfus Aphere Sci. 47:319–325. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ke S, Xu P, Xiong J, Xu L, Ma M, Du X and

Yang R: Long-term poor sleep quality is associated with adverse

donor reactions in college students in Central China: A

population-based cross-sectional study. Vox Sang. 118:455–462.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Eder AF, Notari EP IV and Dodd RY: Do

reactions after whole blood donation predict syncope on return

donation? Transfusion. 52:2570–2576. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Rudokaite J, Ong LLS, Ertugrul IO, Janssen

MP and Veld EMJ: Predicting vasovagal reactions to needles with

anticipatory facial temperature profiles. Sci Rep.

13(9667)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Newman BH, Pichette S, Pichette D and

Dzaka E: Adverse effects in blood donors after whole-blood

donation: A study of 1000 blood donors interviewed 3 weeks after

whole-blood donation. Transfusion. 43:598–603. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Newman BH, Satz SL, Janowicz NM and

Siegfried BA: Donor reactions in high-school donors: The effects of

sex, weight, and collection volume. Transfusion. 46:284–288.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Young I, Parker HM, Rangan A, Prvan T,

Cook RL, Donges CE, Steinbeck KS, O'Dwyer NJ, Cheng HL, Franklin JL

and O'Connor HT: Association between haem and non-haem iron intake

and serum ferritin in healthy young women. Nutrients.

10(81)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hwalla N, Al Dhaheri AS, Radwan H, Alfawaz

HA, Fouda MA, Al-Daghri NM, Zaghloul S and Blumberg JB: The

prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies and inadequacies in the

Middle East and approaches to interventions. Nutrients.

9(229)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Di Santolo M, Stel G, Banfi G, Gonano F

and Cauci S: Anemia and iron status in young fertile

non-professional female athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 102:703–709.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Blood Donor Selection: Guidelines on

assessing donor suitability for blood donation. World Health

Organization, p118, 2013.

|

|

34

|

Meade MA, France CR and Peterson LM:

Predicting vasovagal reactions in volunteer blood donors. J

Psychosom Res. 40:495–501. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ditto B and France CR: Vasovagal symptoms

mediate the relationship between predonation anxiety and subsequent

blood donation in female volunteers. Transfusion. 46:1006–1010.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ditto B, Gilchrist PT and Holly CD:

Fear-related predictors of vasovagal symptoms during blood

donation: It's in the blood. J Behav Med. 35:393–399.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

France CR, France JL, Himawan LK, Stephens

KY, Frame-Brown TA, Venable GA and Menitove JE: How afraid are you

of having blood drawn from your arm? A simple fear question

predicts vasovagal reactions without causing them among high school

donors. Transfusion. 53:315–321. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wieling W, France CR, van Dijk N, Kamel H,

Thijs RD and Tomasulo P: Physiologic strategies to prevent fainting

responses during or after whole blood donation. Transfusion.

51:2727–2738. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Thijsen A and Masser B: Vasovagal

reactions in blood donors: Risks, prevention and management.

Transfus Med. 29 (Suppl 1):S13–S22. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

World Health Organization. (2012). Blood

Donor Selection: Guidelines on Assessing Donor Suitability for

Blood Donation. World Health Organization. Available from:

https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/76724.

|

|

41

|

De Kort WVI: Donor management manual.

DOMAINE project c/o Sanquin Blood Supply Foundation. 2010.

Available from: https://www.sanquin.org/binaries/content/assets/en/research/donor-studies/en-donor-mange

ment-manual-part-1.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2023.

|

|

42

|

Joint United Kingdom (UK) Blood

Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional

Advisory Committee. Guidelines for the Blood Transfusion Services.

2013. Available from: https://www.transfusionguid elines.org/dsg. Accessed

February 6, 2023.

|

|

43

|

Tips For A Successful Blood Donation | Red

Cross Blood Services. Available from: https://www.redcrossblood.org/donate-blood/blood-donat

ion-process/before-during-after.html. Accessed February 6,

2023.

|

|

44

|

Blood donation process at Canadian Blood

Services. Available from: https://www.blood.ca/en/blood/donating-blood/donation-process.

Accessed February 6, 2023.

|

|

45

|

Bonk VA, France CR and Taylor BK:

Distraction reduces self-reported physiological reactions to blood

donation in novice donors with a blunting coping style. Psychosom

Med. 63:447–452. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Hanson SA and France CR: Social support

attenuates presyncopal reactions to blood donation. Transfusion.

49:843–850. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|