Introduction

Growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a (ghrelin

receptor, GHS-R1a) is a specific G protein-coupled receptor

(1). Ghrelin is an endogenous

ligand for GHS-R1a (1) that has

been identified in tissues of the central nervous system, including

the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland (2,3), as

well as in multiple peripheral organs and tissues (4,5),

including the stomach and intestine (6), pancreas (7) and kidney (8).

Ghrelin was initially identified due to its

stimulatory effect on the release of growth hormone (9). Following this discovery, a wide

variety of biological functions of ghrelin were found. Ghrelin is

known to stimulate appetite and acid secretion (10,11)

and a positive energy balance (12), has cardiovascular actions (13) and controls digestive motility

(14,15).

The effect of ghrelin on gastrointestinal tract

motility has been of increasing interest. The central and

peripheral administration of ghrelin increases the gastric emptying

rate (16,17). However, the majority of studies on

the effect of ghrelin on gastrointestinal tract motility have been

performed in normal animals. Although some studies have been

carried out on GHS-R gene-knockout mice (18,19),

the changes in gastrointestinal tract motility in

Ghsr−/− mice have not yet been reported. The aim of this

study was to investigate the effects and possible mechanisms of

GHS-R deficiency on gastric motility in Ghsr−/−

mice.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Ghrelin and carbachol were obtained from Tocris

Cookson (Bristol, UK). GHS-R1a (F-16; goat anti-mouse) and

neurofilament heavy polypeptide (NF-H; H-5; mouse anti-mouse)

antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa

Cruz, CA, USA). Phenol red solution (0.5%) and methylcellulose (400

cp, 2%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse) and

TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody (rabbit anti-goat) were

obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc. (Baltimore Pike, PA,

USA).

Animals

Male and female Ghsr+/− mice (mixed

129S3/SvImJ and C57BL/6J background) were obtained from the

Shanghai Research Center for Model Organisms (Shanghai, China). The

offspring of heterozygous parents underwent genotype identification

for subsequent experiments. GHS-R-knockout mice (Ghsr−/−

mice) and their normal littermates (Ghsr+/+ mice) were

used (20). Animals (10 weeks old,

20–24 g) were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions with a

normal 12/12 h light/dark cycle (21) for at least 7 days prior to the

start of experimentation. Animal procedures were conducted

according to the ethical guidelines of Shanghai Jiao Tong

University. Measurements were performed in conscious animals

following an 18-h fasting period.

Generation and identification of

Ghsr−/− mice

A previously reported approach (19) was used to generate the

Ghsr−/− mice. This procedure was performed in the

Shanghai Research Center for Model Organisms.

The genotypes of the Ghsr+/+ and

Ghsr−/− mice were identified by PCR. Genomic DNA was

extracted from mice tails. The primers were: P1

(5′-GTGCGCACTGTCTCCTCTGAT TTG-3′); P2

(5′-GTGCTTTGGGGTGCGTGTGATGGA-3′) and P3

(5′-CACGCCCACCAGCACGAAGA-3′). The PCR process consisted of 35

amplification cycles (95°C for 5 min, 94°C for 50 sec, 61°C for 50

sec and 72°C for 3 min), with a final elongation period of 10 min

at 72°C. The expected PCR product sizes were 1.9 kbp for the

Ghsr−/− mice and 1.2 kbp for the Ghsr+/+

mice, while two PCR products were expected for Ghsr+/−

mice. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.4%

agarose gel, after which images were captured.

Gastric emptying

All the Ghsr+/+ and Ghsr−/−

mice received gavage feeding of 0.4 ml prewarmed (35°C) phenol red

meal (50 mg/100 ml in distilled H2O with 1.5%

methylcellulose; viscosity 400 centipoise). The mice were

sacrificed by cervical dislocation 20 min after gavage feeding.

Four animals were sacrificed immediately after the gavage feeding

to serve as internal controls. The entire stomach was carefully

isolated, ligated just above the cardia and below the pylorus, and

removed. Gastric emptying measurements were performed as described

previously (22,23). The stomach and its contents (phenol

red meal plus possible gastric secretions) were homogenized with 10

ml NaOH (0.1 N). The mixture was kept at room temperature for 1 h.

The supernatant (5 ml) was added to 0.5 ml trichloroacetic acid

solution (20%, w/v) to precipitate any proteins. After centrifuging

(2500 × g, 20 min), 5 ml supernatant was added to 4 ml NaOH (0.5 N)

to develop the maximum intensity of color. The solutions were read

at a wavelength of 560 nm with a spectrophotometer (Shanghai Yixian

Co., Shanghai, China). The percentage of gastric emptying (GE%) was

determined as: GE% = (1-X/Y) × 100, where X and Y are the

absorbances of phenol red collected from the stomachs of animals

sacrificed 20 min after gavage and immediately after gavage

feeding, respectively.

The gastric emptying rates were studied following

the intraperitoneal administration of 0, 20, 40 or 80 μg/kg

ghrelin. Ghrelin was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl. The intraperitoneal

administration volume (ghrelin plus saline solution) was 0.2

ml.

Organ bath

Contractility measurements of smooth muscle

strips

Ghsr+/+ and Ghsr−/− mice were

fasted for 18 h and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Circular

muscle strips, freed from mucosa (length 10 mm, width 1 mm) were

cut from the gastric antrum and suspended vertically in an organ

bath filled with Krebs solution (121.5 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM

CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM

KH2PO4, 25.0 mM NaHCO3 and 11.0 mM

glucose). The organ bath chamber was gassed with 95%

O2/5% CO2 and warmed to 37°C. Figures

obtained from the isometric force transducer (Harvard Apparatus,

South Natick, MA, USA) were continuously recorded and stored on a

computer and analyzed using the SMUP-E biological signal processing

system (Chengdu Equipment Factory, Chengdu, China). The initial

load was set at 0.5 g for each strip. The Krebs solution was

changed every 15 min and the organ bath was allowed to equilibrate

for 1 h. Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was applied to the

preparation through a pair of platinum ring electrodes fixed on the

top and bottom of the bath. A frequency spectrum (4 Hz) was

obtained using pulse trains (duration 1 msec, train 10 sec, 2-min

intervals) (24,25).

The contractile responses of the smooth muscle

strips to EFS (4 Hz) and ghrelin (0.01, 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 μM) plus

EFS (4 Hz) were observed in the control and model mice. The

amplitude of contraction or relaxation of the strips was normalized

using the responses evoked by EFS in the absence of ghrelin to

evaluate the ghrelin-induced action. The EFS-induced action was

normalized using the amplitude of spontaneous contraction or

relaxation.

Contractility measurements of isolated

stomach

Intragastric pressure levels were used to evaluate

the reactive ability of all the gastric muscle layers to

experimental substances as described in previous studies (26). The entire stomach was carefully

isolated, removed and placed in Krebs solution. The stomach content

(possible meal and gastric secretions) was flushed with Krebs

solution. A soft polyethylene catheter (inner diameter, 1.7 mm;

outer diameter, 2.2 mm) was implanted through the pylorus into the

gastric cavity and connected to an external pressure transducer

(Harvard Apparatus). Figures were recorded and stored on a computer

for analysis using the SMUP-E biological signal processing system.

The intragastric pressure was initially kept at 5 cm H2O

and allowed to equilibrate for 1 h. The buffer was changed every 15

min. Measurements were taken when spontaneous pressure fluctuations

were relatively stable.

The intragastric pressure responses to carbachol

(50, 100, 200, 400 and 600 nM) were observed in the organ bath. The

effect of carbachol on intragastric pressure was normalized by the

mean of three maximal spontaneous pressure wave peak values.

Immunofluorescence staining

GHS-R staining in gastric muscle layers

Fluorescent staining of GHS-Rs in the gastric antrum

muscle layers was studied in Ghsr+/+ and

Ghsr−/− mice. Gastric muscle layers, freed from mucous

layers, were fixed on a platform and stretched to ~150%. The

samples were subsequently fixed with 4°C acetone for 15 min, after

which the acetone was washed off with PBS. The samples were then

incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min and flushed, after

which they were incubated with 10% fetal bovine serum for 60 min.

The primary antibody to GHS-R1a (F-16; goat anti-mouse) was diluted

in PBS and added to the muscle tissues at a ratio of 1:100. The

samples were incubated at 4°C for 2 days. The secondary antibody

(rabbit anti-goat) coupled with rhodamine (TRITC, red fluorescence)

was diluted in PBS and added to the fixed samples at a ratio of

1:200. The tissues were then incubated for half a day in a dark

room. DAPI was used as a counterstain for the cell nuclei. The

samples were then coverslipped with 50% glycerol. Negative controls

were prepared in the same manner as the samples, but without

application of the primary antibody.

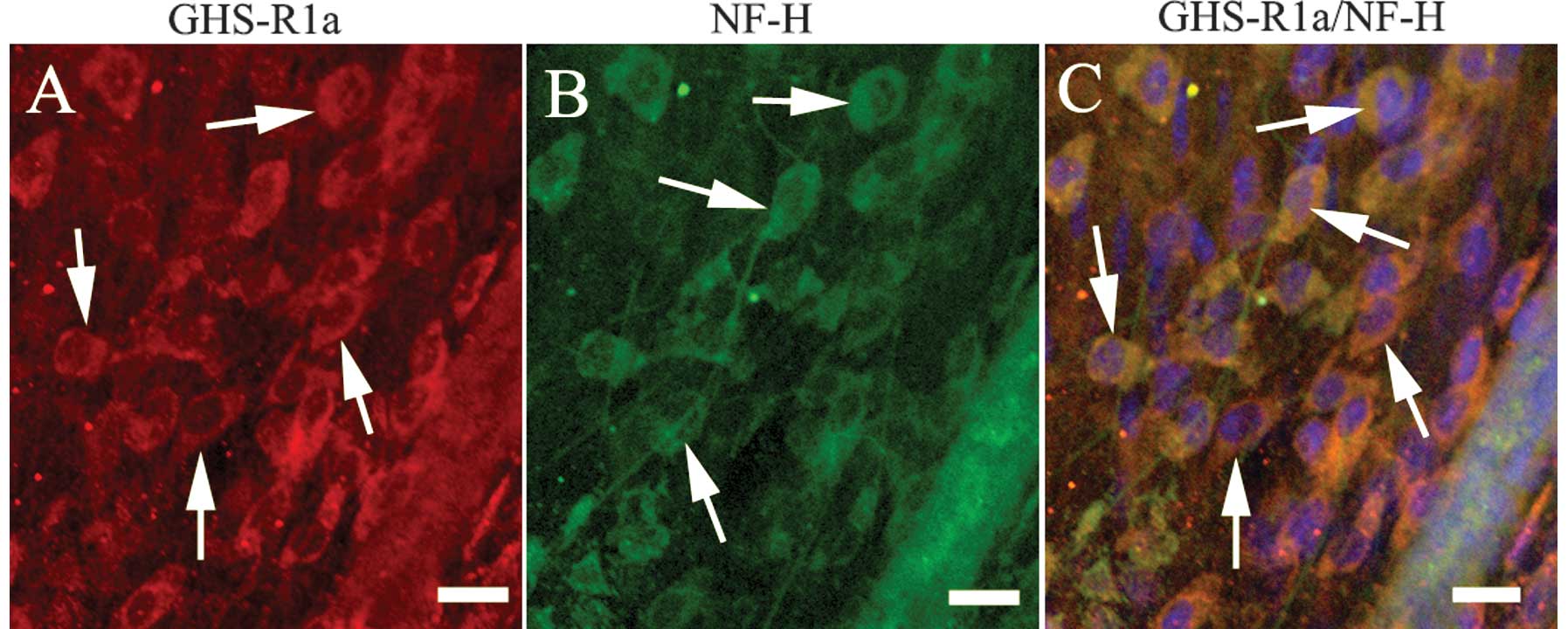

Double fluorescent staining of the nerve cells in

the gastric antrum muscle layers was studied in the

Ghsr+/+ and Ghsr−/− mice. The GHS-R1a

antibody (F-16) was used to label the GHS-Rs and the NF-H antibody

(H-5), a neuron-specific marker, was used to label the nerve cells.

The procedures of staining were as described above. The dilution

rates of the primary antibodies GHS-R1a (F-16; goat anti-mouse) and

NF-H (H-5; mouse anti-mouse) were 1:100. The dilution rates of the

secondary antibodies, coupled with rhodamine (TRITC, rabbit

anti-goat) or fluorescein (FITC, goat anti-mouse), were 1:200. The

samples were examined and scanned under a laser confocal microscope

(Olympus, FV-1000, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data were

analyzed with Origin 8.0 software. Photoshop 8.0.1 and CorelDRAW X4

software were used to produce the figures. Data recordings were

evaluated by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by

Dunnett’s test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant result.

Results

Gastric emptying in Ghsr+/+

and Ghsr−/− mice

The GE% values were significantly reduced in the

Ghsr−/− mice when no drug was injected (Fig. 1A). Ghrelin increased the GE% in a

dose-dependent manner in the Ghsr+/+ mice when

intraperitoneally administered, but had no effect on the GE% in the

Ghsr−/− mice (Fig.

1B).

| Figure 1Gastric emptying rates (GE%) in

Ghsr+/+ and Ghsr−/− mice. (A) GE% for 20 min

when no drugs were injected, *P<0.05; (B) GE% for 20

min following the intraperitoneal administration of ghrelin.

P-values indicate differences of gastric emptying rates between

control and model mice when the same dose or different doses of

drugs were administered. aP<0.01,

a,bP<0.01, b,cP<0.01;

a′P>0.05, a′,b′P>0.05,

b′,c′P>0.05, a′,c′P>0.05;

a,a′P<0.01, b,b′P<0.01,

c,c′P<0.01, n=4 per condition. Mean ± SEM. |

Organ bath

Smooth muscle strips

When EFS (4 Hz) was applied in vitro, the

contractile response of the smooth muscle strips was lower in the

strips from the Ghsr−/− mice than in those from the

Ghsr+/+ mice (Fig.

2A).

In the strips from the Ghsr+/+ mice,

ghrelin (0.01, 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 μM) increased the amplitude of

contraction or relaxation of the strips in a dose-dependent manner

in the presence of EFS, while in the strips from the

Ghsr−/− mice, this effect was not observed (Fig. 2A). There were statistically

significant differences in the contractile amplitudes of the strips

from the two types of mice when EFS and EFS plus ghrelin were

applied (Fig. 2B and C).

Isolated stomach

The changes of the intragastric pressure levels were

lower in the Ghsr−/− mice than in the Ghsr+/+

mice when carbachol (50, 100, 200, 400 and 600 nM) was applied to

the isolated stomach (Fig. 3A).

There were statistically significant differences in the

intragastric pressure levels when different concentrations of

carbachol were administered (Fig.

3B).

Immunofluorescent staining of gastric muscle

layer nerve cells

Immunofluorescent staining indicated that GHS-R1as

(red fluorescence) were present in the Ghsr+/+ mice

(Fig. 4A) but not in the

Ghsr−/− mice (data not shown). In the Ghsr+/+

mice, GHS-R1as were mainly located on the membrane and the

cytoplasms of the nerve cells in the gastric antrum muscle plexus

(Fig. 4C).

Immunofluorescent staining of the nerve cells in the

gastric antrum muscle layer in the Ghsr+/+ and

Ghsr−/− mice is shown in Fig. 5A. The number of nerve cells in the

gastric antrum muscle layer was decreased in the Ghsr−/−

mice (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

In previous studies, the administration of ghrelin

via the central nervous system has been demonstrated to have a

pronounced effect on appetite and the motility of the

gastrointestinal tract (27–29).

Centrally, ghrelin acts through activation of GHS-Rs in the

hypothalamus. These effects are mediated by the vagal nerve

(30). When the vagal nerve is

severed, central effects are eliminated (31). The peripheral administration of

ghrelin also enhances the motility of the gastrointestinal tract

(32–34). The peripheral effects of ghrelin

may be caused by the activation of GHS-Rs on the vagal nerve

(14) and gastrointestinal enteric

plexus (35). Ghrelin exerts its

effects by activating GHS-Rs in central or peripheral tissues

(2–5).

In Ghsr−/− mice, GHS-Rs are defective due

to the knockout of GHS-R genomic DNA. This is likely to influence a

number of the effects mediated by ghrelin, including the promotion

of gastrointestinal tract motility. Sun et al reported that

the body weights of Ghsr−/− mice, regardless of high fat

or regular diet, were slightly lower than those of their wild-type

littermates (P<0.05) (18), and

food intake following fasting was identical in Ghsr+/+

and Ghsr−/− mice, indicating that the absence of the

Ghsr in obese mice does not prevent weight gain following weight

loss. Some of these results were obtained from obese rather than

non-obese mice. Thus, there may be differences in food intake and

gastric motility in non-obese mice, and further studies should be

conducted.

Our experimental results in vivo demonstrated

that gastric emptying rates were reduced in Ghsr−/−

mice. Ghrelin promoted gastric emptying rates in a dose-dependent

manner in Ghsr+/+ mice. In Ghsr−/− mice, no

effect of ghrelin on gastric emptying rates was observed. In

Ghsr+/+ mice, GHS-Rs are expressed normally, allowing

ghrelin to exert its biological functions by activating GHS-Rs in a

dose-dependent manner, while in Ghsr−/− mice, the

gastric emptying induced by ghrelin was eliminated, which may

involve changes to the central and peripheral channels. The absence

of the GHS-Rs in the central system may attenuate the effect of the

hypothalamus on gastric motility, while the absence of GHS-Rs in

the stomach may eliminate the peripheral effect of ghrelin on

gastric motility. Ghrelin was administered at physiological

stimulus doses of 20, 40 and 80 μg/kg. Under physiological

conditions, the plasma levels of ghrelin in rats are 500–2000

pmol/l (36). Fujino et al

reported that the injection of 1.5 nmol ghrelin in rats resulted in

an ~600 pmol/l increase in plasma ghrelin concentrations (14). This result is supported by our

finding that the plasma concentrations of ghrelin were ~2400 pmol/l

following the administration of 80 μg/kg ghrelin, which approached

physiological concentrations.

In vitro, EFS induced a contractile response

in smooth muscle strips, and the amplitudes of contraction or

relaxation of the strips differed between the Ghsr+/+

and Ghsr−/− mice. The different contractile responses of

the smooth muscle strips, we hypothesize, may relate to the

functions and states of the smooth muscle cells or nerve cells in

the muscle layers. The effects of ghrelin on the isolated strips

were the same as those observed in vivo. These results

indicate that ghrelin is able to induce a contractile response in

smooth muscle strips from Ghsr+/+ mice only when the

strips are stimulated through excitatory nerves. In vivo,

ghrelin is not able to induce a contractile response directly, but

enhances the amplitudes of contraction or relaxation of the strips

induced by EFS. In Ghsr−/− mice, the absence of the Ghsr

in the strips may negate the effect of ghrelin on the contractile

response of the smooth muscle strips.

In vitro, ghrelin played a

gastroprokinetic-like role when smooth muscle strips were

stimulated by an electrical field (24). This finding suggests that ghrelin

exerts its effect only in response to excitatory nerve impulses or

changes in membrane potential, i.e., it is able to enhance but not

directly induce smooth muscle cell contraction. In the current

study, we found that a single administration of ghrelin did not

affect intragastric pressure levels. No effects were observed even

though the increased dose of ghrelin exceeded physiological

concentrations 50-fold (data not shown), which is in accordance

with results previously obtained from gastric smooth muscle strips

(24). This may be as a result of

the effect of ghrelin on gastric motility being mediated by the

activation of GHS-Rs located on nerve cells in the gastric plexus,

i.e., when the stomach was isolated, the motor nerves were cut off

and the functions of the gastric plexus downstream from the motor

nerves were suppressed. Intragastric pressure levels were lower in

the Ghsr−/− mice than in the Ghsr+/+ mice

when the same dose of carbachol was administered, suggesting that

the reactive ability of gastric muscle layers to carbachol was

altered in the Ghsr−/− mice. This may be related to the

deficiency of GHS-Rs and the functions and states of the smooth

muscle cells or nerve cells in the gastric plexus. In

Ghsr+/+ mice, the effect of carbachol was likely to be

enhanced by ghrelin (37,38), which is secreted by mucous X/A-like

cells (9).

Fluorescent staining results supported the results

obtained from the in vivo and in vitro studies. The

fluorescent staining of gastric muscle tissues indicated that

GHS-Rs were mainly located on nerve cells in the gastric plexus.

This result morphologically supports the previous theory that

ghrelin acts through the nerve cells in the gastrointestinal plexus

(24,39). GHS-Rs were not detected in muscle

layers in the Ghsr−/− mice, which demonstrated the

reliability of the knockout of GHS-R genomic DNA. Thus, loss of

GHS-Rs eliminated the gastroprokinetic-like role mediated by

ghrelin in the Ghsr−/− mice, and the central and

peripheral effects of ghrelin were also eliminated. The number of

nerve cells in the gastric antrum muscle layers was decreased in

the Ghsr−/− mice, which may affect the release of

excitatory neurotransmitters, i.e., the quantity of

neurotransmitters released from nerve cells in the gastric plexus

may be decreased in Ghsr−/− mice when the same intensity

of EFS and concentration of carbachol are applied. The decrease in

the number of nerve cells in the gastric plexus and the loss of

GHS-Rs in muscle layers may together lead to the decrease in the

contractility of gastric smooth muscle to EFS and carbachol in

vitro. Since the functions and states of the smooth muscle

cells themselves are unknown, further studies should be

performed.

In summary, GHS-R-deficient mice were a platform to

study the effects of the ghrelin receptors. In the present study,

the ghrelin receptor deficiency weakened gastric motility. The

knockout of ghrelin receptor genomic DNA may affect the development

of nerve cells in the gastric plexus and lead to a reduction in the

number of nerve cells. The loss of ghrelin receptors in muscle

layers and of nerve cells in the gastric plexus may together

attenuate gastric motility. However, more studies should be carried

out to clarify the mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Shanghai Research

Center for Model Organisms for participation in the study. This

study was supported in part by the Physiology Laboratory, Shanghai

Jiaotong University and was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (No. 30400429).

References

|

1

|

van der Lely AJ, Tschöp M, Heiman ML and

Ghigo E: Biological, physiological, pathophysiological, and

pharmacological aspects of ghrelin. Endocr Rev. 25:426–457.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Guan XM, Yu H, Palyha OC, et al:

Distribution of mRNA encoding the growth hormone secretagogue

receptor in brain and peripheral tissues. Brain Res Mol Brain Res.

48:23–29. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shuto Y, Shibasaki T, Wada K, et al:

Generation of polyclonal antiserum against the growth hormone

secretagogue receptor (GHS-R): evidence that the GHS-R exists in

the hypothalamus, pituitary and stomach of rats. Life Sci.

68:991–996. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kojima M, Hosoda H and Kangawa K:

Purification and distribution of ghrelin: the natural endogenous

ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Horm Res.

56(Suppl 1): S93–S97. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yokote R, Sato M, Matsubara S, et al:

Molecular cloning and gene expression of growth hormone-releasing

peptide receptor in rat tissues. Peptides. 19:15–20. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Date Y, Kojima M, Hosoda H, et al:

Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is

synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the

gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology.

141:4255–4261. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kamegai J, Tamura H, Shimizu T, et al:

Central effect of ghrelin, an endogenous growth hormone

secretagogue, on hypothalamic peptide gene expression.

Endocrinology. 141:4797–4800. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mori K, Yoshimoto A, Takaya K, et al:

Kidney produces a novel acylated peptide, ghrelin. FEBS Lett.

486:213–216. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, et al: Ghrelin

is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach.

Nature. 402:656–660. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dimaraki EV and Jaffe CA: Role of

endogenous ghrelin in growth hormone secretion, appetite regulation

and metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 7:237–249. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Arakawa M, Suzuki H, Minegishi Y, et al:

Enhanced ghrelin expression and subsequent acid secretion in mice

with genetic H(2)-receptor knockout. J Gastroenterol. 42:711–718.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Asakawa A, Inui A, Fujimiya M, et al:

Stomach regulates energy balance via acylated ghrelin and desacyl

ghrelin. Gut. 54:18–24. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Nagaya N and Kangawa K: Ghrelin, a novel

growth hormone-releasing peptide, in the treatment of chronic heart

failure. Regul Pept. 114:71–77. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fujino K, Inui A, Asakawa A, et al:

Ghrelin induces fasted motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract

in conscious fed rats. J Physiol. 550:227–240. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tack J, Depoortere I, Bisschops R, et al:

Influence of ghrelin on interdigestive gastrointestinal motility in

humans. Gut. 55:327–333. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Taniguchi H, Ariga H, Zheng J, et al:

Effects of ghrelin on interdigestive contractions of the rat

gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol. 14:6299–6302. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Trudel L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC, et al:

Ghrelin/motilin-related peptide is a potent prokinetic to reverse

gastric postoperative ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

Physiol. 282:G948–G952. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sun Y, Butte NF, Garcia JM and Smith RG:

Characterization of adult ghrelin and ghrelin receptor knockout

mice under positive and negative energy balance. Endocrinology.

149:843–850. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sun Y, Wang P, Zheng H and Smith RG:

Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is

mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:4679–4684. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen D, Zhao CM, Håkanson R, et al:

Altered control of gastric acid secretion in

gastrin-cholecystokinin double mutant mice. Gastroenterology.

126:476–487. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nicklas W, Baneux P, Boot R, et al:

Recommendations for the health monitoring of rodent and rabbit

colonies in breeding and experimental units. Lab Anim. 36:20–42.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Scarpignato C, Capovilla T and Bertaccini

G: Action of caerulein on gastric emptying of the conscious rat.

Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 246:286–294. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Amira S, Soufane S and Gharzouli K: Effect

of sodium fluoride on gastric emptying and intestinal transit in

mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 57:59–64. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kitazawa T, De Smet B, Verbeke K, et al:

Gastric motor effects of peptide and non-peptide ghrelin agonists

in mice in vivo and in vitro. Gut. 54:1078–1084. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Nakamura T, Onaga T and Kitazawa T:

Ghrelin stimulates gastric motility of the guinea pig through

activation of a capsaicin-sensitive neural pathway: in vivo and in

vitro functional studies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 22:446–452.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Mulè F, Amato A, Baldassano S and Serio R:

Involvement of CB1 and CB2 receptors in the modulation of

cholinergic neurotransmission in mouse gastric preparations.

Pharmacol Res. 56:185–192. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kamiji MM, Troncon LE, Suen VM and de

Oliveira RB: Gastrointestinal transit, appetite, and energy balance

in gastrectomized patients. Am J Clin Nutri. 89:231–239. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kobashi M, Yanagihara M, Fujita M, et al:

Fourth ventricular administration of ghrelin induces relaxation of

the proximal stomach in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp

Physiol. 296:R217–R223. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tups A, Helwig M, Khorooshi RM, et al:

Circulating ghrelin levels and central ghrelin receptor expression

are elevated in response to food deprivation in a seasonal mammal

(Phodopus sungorus). J Neuroendocrinol. 16:922–928. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ammori JB, Zhang WZ, Li JY, et al: Effects

of ghrelin on neuronal survival in cells derived from dorsal motor

nucleus of the vagus. Surgery. 144:159–167. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kamiji MM, Troncon LE, Antunes-Rodrigues

J, et al: Ghrelin and PYY(3–36) in gastrectomized and vagotomized

patients: relations with appetite, energy intake and resting energy

expenditure. Eur J Clin Nutr. 64:845–852. 2010.

|

|

32

|

Edholm T, Levin F, Hellström PM and

Schmidt PT: Ghrelin stimulates motility in the small intestine of

rats through intrinsic cholinergic neurons. Regul Pept. 121:25–30.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kobelt P, Tebbe JJ, Tjandra I, et al: CCK

inhibits the orexigenic effect of peripheral ghrelin. Am J Physiol

Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 288:R751–R758. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kleinz MJ, Maguire JJ, Skepper JN and

Davenport AP: Functional and immunocytochemical evidence for a role

of ghrelin and des-octanoyl ghrelin in the regulation of vascular

tone in man. Cardiovasc Res. 69:227–235. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Murakami N, Hayashida T, Kuroiwa T, et al:

Role for central ghrelin in food intake and secretion profile of

stomach ghrelin in rats. J Endocrinol. 174:283–288. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bassil AK, Dass NB and Sanger GJ: The

prokinetic-like activity of ghrelin in rat isolated stomach is

mediated via cholinergic and tachykininergic motor neurones. Eur J

Pharmacol. 544:146–152. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Qiu WC, Wang ZG, Wang WG, et al:

Therapeutic effects of ghrelin and growth hormone releasing peptide

6 on gastroparesis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic guinea pigs

in vivo and in vitro. Chinese Med J (Engl). 121:1183–1188.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dass NB, Munonyara M, Bassil AK, et al:

Growth hormone secretagogue receptors in rat and human

gastrointestinal tract and the effects of ghrelin. Neuroscience.

120:443–453. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Depoortere I, De Winter B, Thijs T, et al:

Comparison of the gastroprokinetic effects of ghrelin, GHRP-6 and

motilin in rats in vivo and in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 515:160–168.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|