Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium

tuberculosis (MTB) has the highest mortality rate worldwide of

any infectious disease and has been declared a global health

emergency by the World Health Organization (1,2). The

attenuated M. bovis Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) is the

only available vaccine against TB. However, BCG exhibits varying

efficacy (0-80%) against adult pulmonary TB (3). Emergence of drug-resistant isolates

of MTB highlight the continued necessity for the discovery and

development of drugs active against the bacterium (4–8).

Aptamers have high affinity and specificity for

their targets and have been developed for use as oligonucleotide

analogs of antibodies. These molecules exhibit several advantages

over antibodies and antibiotics. Aptamers are smaller than

antibodies and therefore exhibit improved cell penetration, blood

clearance and chemical modification. They are also nonimmunogenic

and readily synthesized and therefore do not induce an immune host

response, which may cause harmful side-effects (9,10).

Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) aptamers exhibit more variable

structures, longer relative temperature stability and shelf-life

than antibodies and therefore demonstrate significant potential for

in vivo use as therapeutics (11,12).

In previous years the Systematic Evolution of

Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) technique has become

increasingly important for the study of protein function, as well

as in drug discovery and identification of antagonists against a

number of functional proteins (13,14).

However, little is known regarding the in vitro SELEX

selection strategy utilized for the generation of inhibitors

against whole bacteria. Our previous study extracted special

aptamers (NK2) and aptamer pools (10th pool) from a whole bacterial

SELEX strategy (15) and

demonstrated that aptamers inhibit MBT H37Rv invasion of

macrophages in vitro(16).

In the present study, we further evaluated the function of the 10th

pool and NK2 against MBT H37Rv in a mouse model. This investigation

may aid the development of a new antitubercular agent based on an

aptamer species.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and animals

MTB H37Rv (strain ATCC 93009) was purchased from the

Beijing Biological Product Institute (Beijing, China). Bacteria

were maintained on Lowenstein-Jensen (L-J) medium and harvested in

log phase growth. Prior to use, bacilli were washed in 0.05%

Tween-80 saline and triturated to uniformity. C57BL/6 mice (from

the Experimental Building of the Animal Laboratory Center, Wuhan

University, Wuhan, China) of either sex were used at 5–6 weeks of

age. Bacterial cultures and animal tests were performed in the

Animal Biosafety Level 3 Laboratory (ABSL-III) of Wuhan University

School of Medicine. The research procedures and the animal

protocols in this study were approved by the HPKLTM Ethics &

Animal Use Committee (approval ID: HPKLTME201005).

Fluorescence microscopy and phagocytic

index

C57BL/6 mouse peritoneal macrophages were collected

and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS and penicillin and

streptomycin. Following 48 h, cell number was estimated using

trypan blue staining. To analyze the effect of aptamers on H37Rv

invasion of macrophages, 108 cfu H37Rv bacteria was

incubated with aptamers (pretreated at 85°C for 15 min and then

incubated on ice for 3 min) at 37°C for 15 min (control group was

untreated with aptamer). Following this, centrifugation at 12,000

rpm for 5 min was performed and the supernatant was discarded.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages (106) were mixed with

108 cfu H37Rv in 2 ml medium. Phagocytosis was allowed

to occur for 1 h during mixing at 37°C in 6-well costar plates. A

pretreated (polylysine, 0.1 mg/ml) coverslip was applied to each

analytic well. The coverslip was dislodged and fixed by frigorific

acetone and then stained with auramine O. The coverslip was then

observed under a fluorescence microscope (CW4000, Leica, Wetzlar,

Germany). Counts of 200 cells from each coverslip were performed

and the phagocytic index was calculated using the formula:

phagocytic index = (total MTB phagocytosed by

macrophage)/(macrophage number of phagocytosed MTB).

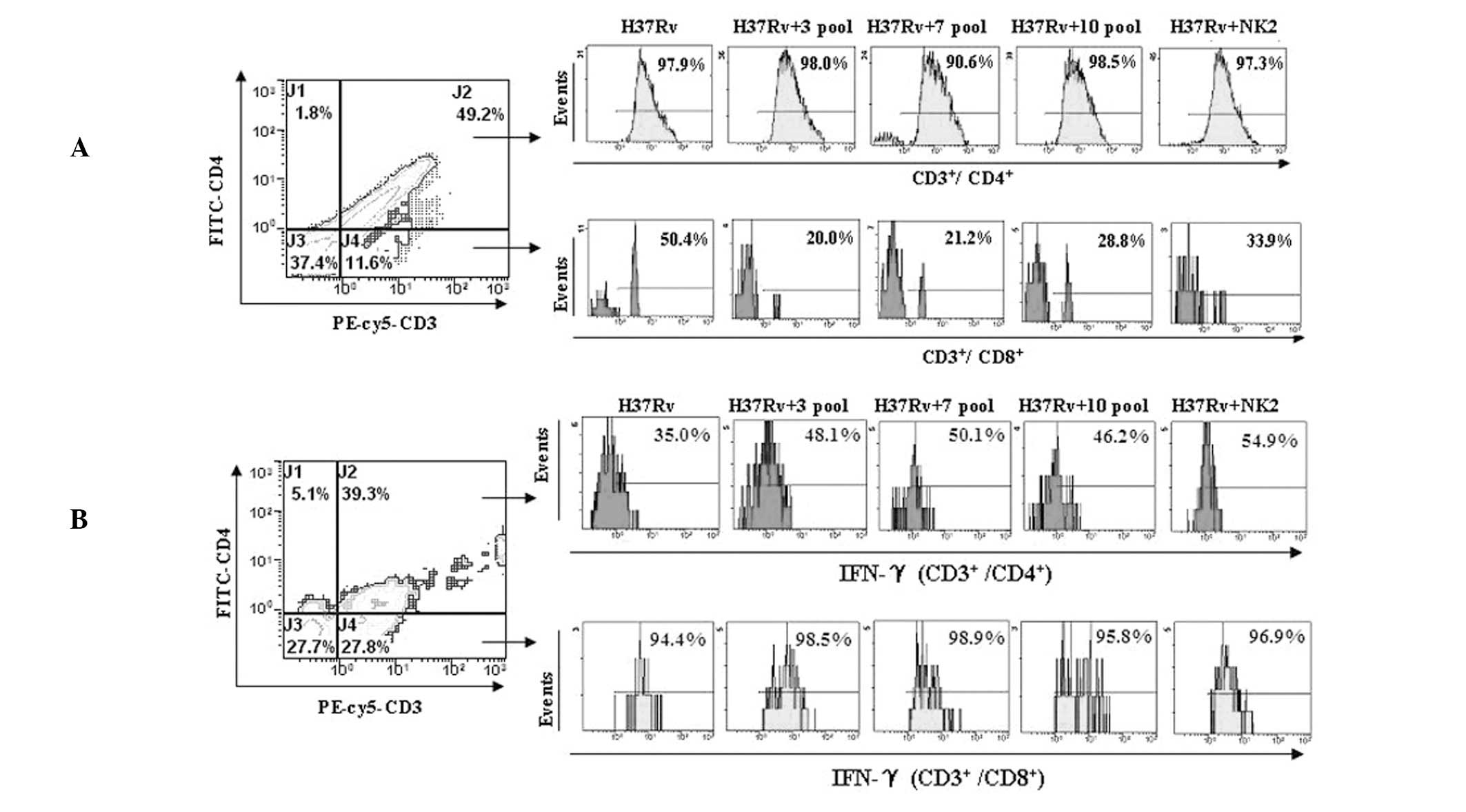

Flow cytometry analysis of the effect of

aptamers on the invasion of H37Rv to CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells

H37Rv (108 cfu; prestained with Rhodamine

B) was incubated for 1 h with 106 peripheral blood

mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from the tail vein of C57BL/6

mice. Experimental groups were pretreated with the 10th pool or NK2

as previously described (15).

Following this, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated

with 5 μl mouse anti-CD3-PE-Cy5, anti-CD4-FITC (Caltag

Laboratories, Buckingham, UK) or isotype control antibodies, at the

concentration recommended by the manufacturer’s instructions, for

30 min at 4°C. The cells were then fixed with 70% ethanol and

analyzed using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; Epics

Altra II, Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA).

Effect of aptamers on the intracellular

expression of IFN-γ of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

in H37Rv-infected splenocytes

Murine splenocytes (2×106)were incubated

with 108 cfu H37Rv or pretreated with the 10th pool and

NK2 for 1 h. Following this, 1 μg/ml monensin (eBioscience, San

Diego, CA, USA) was added and incubated at 37°C for 2 h in a 5%

(v/v) CO2 atmosphere. Cells were washed twice with PBS,

resuspended in 100 μl cold PBS and incubated with 5 μl mouse

anti-CD3-PE-Cy5 and anti-CD4-FITC antibodies (Caltag Laboratories)

at 4°C for 30 min. The cells were fixed using 70% ethanol and

incubated with 5 μl PE-conjugated mouse anti-IFN-γ (Caltag

Laboratories) at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Stained cells were

washed with PBS and intracellular cytokine expression of IFN-γ in

CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+

T cells was analyzed by FACS.

Challenge infection and analysis of

survival rate

C57BL/6 female mice (18–22 g) were used in the

study. H37Rv bacteria used for in vivo experiments underwent

several passages in C57BL/6 mice to enhance virulence (17). Mice were injected intravenously

with 107 cfu H37Rv/mouse in 0.4 ml saline. Equal MTB was

pretreated with 8 μg of the 10th pool or NK2 aptamers, the

supernatant was then discarded, and pellets were centrifuged prior

to injection with 0.4 ml saline. Mice were fed with standard

pelleted food and water for 20 days and each group was composed of

8 mice. Mortality was monitored daily. Survival analysis was

analyzed by Kaplan-Meier (SPSS 13.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Histopathology and acid-fast stain

Lungs or spleens from mice sacrificed 20 days

post-infection were homogenized in saline and plated on L-J medium.

Following 4–6 weeks incubation at 37°C, the number of viable

organisms in the lungs or spleens was determined. Sections of the

lungs and spleens were soaked in 10% paraformaldehyde for a minimum

of 12 h and examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain and acid-fast

stain, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the mean ± SEM and were

analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the

Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Inhibition of MTB invasion of mouse

peritoneal macrophages

Compared with untreated, groups pretreated with

aptamers (NK2 or 10th pool) inhibited MTB invasion of mouse

peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 1A).

Similar results were obtained by comparing the phagocytic index

with fluorescence microscope observations (Fig. 1B). MTB invasion of mouse peritoneal

macrophages was higher in NK2 than the 10th pool.

Inhibition of H37Rv invasion to

CD3+ CD8+ T cells

H37Rv invasion to CD3+ CD8+ T

cells was inhibited by the aptamers. Invasion to CD3+

CD4+ T cells was not inhibited. H37Rv invasion to

CD3+ CD8+ T cells was found to be

significantly decreased from 50.4% (without aptamers) to 33.9, 28,

21 and 20% with NK2 aptamer, 10th, 7th and 3rd aptamer pool,

respectively (Fig. 2A). These data

indicate that aptamer pools protect CD8+ T cells against

H37Rv infection.

Aptamers increase intracellular IFN-γ

secretion of CD3+ CD4+ T cells

Intracellular IFN-γ levels in CD3+

CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ T cells were

detected by flow cytometry. When PBMCs from mice were infected by

H37Rv in vitro, increased levels of intracellular IFN-γ were

observed in the presence of aptamers in CD3+

CD4+ T cells, but not in CD3+/CD8+

T cells. Intracellular IFN-γ levels in CD3+

CD4+ T cells were increased from 35% (without aptamers)

to 48.1, 50.1, 46.2, 53.6 and 54.9% with 3rd, 7th, 10th and 12th

aptamer pools and NK2 aptamer, respectivly. The NK2 aptamer had the

strongest stimulatory effect on intracellular IFN-γ levels in

CD3+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that

aptamers, particularly the NK2 aptamer, stimulate IFN-γ production

and decrease the infection efficiency of MTB.

Treatment of H37Rv in vivo

Effect of 10th round aptamer pool or NK2 aptamer on

acute tuberculosis in mice was examined. In the control group,

H37Rv injection for 13 days, resulted in 50% mortality. Survival

rate of the mice was prolonged for 2 days with a single injection

of aptamer NK2 and 3 days with a single injection of aptamer pool

(10th round selection; P<0.05; Fig.

3). Histopathological examination of lungs from mice injected

with H37Rv revealed a marked acute inflammatory reaction compared

with normal mice. NK2- or aptamer pool treated-mice demonstrated

decreased pulmonary alveoli fusion and swelling and more prominent

air spaces, similar to lungs of normal mice (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, compared with

normal mice the density of acid fast bacillus in the lung was

higher in control mice than mice that had received a single

injection of aptamer NK2 or 10th pool aptamers (Fig. 4B). Number of H37Rv colonies was

higher in control mice than in the 10th aptamer pool or NK2 groups

(Fig. 4C). The present study

revealed that, in vivo, the 10th pool of aptamers and NK2

had an active therapeutic effect on H37Rv infection and the 10th

pool of aptamers was more effective than NK2.

Discussion

The use of aptamers as therapeutic drugs has been

reported in numerous research fields, including HIV (18) and cancer (19). Aptamers may inhibit MTB infection

through blockage of virulence components or epitopes of H37Rv.

In vitro, inhibition of H37Rv macrophage infection by NK2

aptamers was higher when compared with the 10th aptamer pool

(Fig. 1), however, the 10th

aptamer pool prolonged the survival rate of mice, enhancing

clearance of the bacterium in vivo to a more significant

degree (Figs. 3 and 4). This may be due to the complex surface

of MTB and the degradation of DNA aptamers by nuclease enzymes

(20). The 10th aptamer pool

contained various non-special aptamers that may aid resistance to

nucleases and function in synergy with the NK2 aptamer. Thus, the

10th aptamer pool was more effective than the NK2 aptamer in

vivo. Previously, modified aptamers with longer half-lives were

developed to resist nuclease digestion. However, disadvantages have

been identified, including an increased rate of integration into

the chromosomal DNA of host T cells. There are multiple binding

sites and antigen epitopes on the surface of H37Rv and synergism of

several aptamers is required to inhibit H37Rv infection. In the

present study, we noted that inhibition of H37Rv invasion to

CD8+ T cells decreased as the screening process

progressed (Fig. 2A). This

observation may be due to inhibitory aptamers being missed through

SELEX. This may be explained by important components in the reverse

target (BCG) which stimulate the cytotoxic T-cell effect.

Currently, BCG is the only vaccine against tuberculosis, however,

its immune protective effects are not always effective. A possible

explanation for reduced efficacy may be due to the effect of

aptamers on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2).

The present study demonstrates that the aptamer pool

and NK2 aptamer exhibit protection against tuberculosis, however,

their mechanisms of action are different. NK2 revealed improved

inhibition of H37Rv invasion to mice peritoneal macrophages and

stimulation of CD4+ T-cell INF-γ secretion compared with

the 10th pool. However, survival rate and histological analysis

revealed that the 10th pool has a better therapeutic effect

compared with NK2. The results demonstrated we should not only pay

attention to those aptamers in the majority (including NK2), but

also investigate the role of early deserted aptamers. The present

study demonstrates the limitations of ssDNA aptamers, highlighting

a number of factors which must be considered to avoid available

aptamer loss.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Wuhan Health Bureau

Funded Projects (WH12A03) and the Hainan Natural Science Fund (nos.

808162 and 812199).

References

|

1

|

Raviglione MC, Dye C, Schmidt S and Kochi

A: Assessment of worldwide tuberculosis control. WHO global

surveillance and monitoring project. Lancet. 350:624–649. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V and

Raviglione MC: Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis:

estimated incidence, prevalence and mortality by country WHO Global

Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA. 282:677–686. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fine PE: Variation in protection by BCG:

implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet.

346:1339–1345. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pablos-Mendez A, Raviglione MC, Laszlo A,

Binkin N, Rieder HL, Bustreo F, Cohn DL, Lambregts-van Weezenbeek

CS, Kim SJ, Chaulet P and Nunn P: Global surveillance for

antituberculosis-drug resistance 1994–1997. World Health

Organization-International Union against tuberculosis and lung

disease working group on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance

surveillance. N Engl J Med. 338:1641–1649. 1998.

|

|

5

|

Ahmed N and Hasnain SE: Genomics of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis: old threats and new trends.

Indian J Med Res. 120:207–212. 2004.

|

|

6

|

Baptista IMFD, Oelemann MC, Opromolla DVA

and Suffys PA: Drug resistance and genotypes of strains of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from human

immunodeficiency virus-infected and non-infected tuberculosis

patients in Bauru, São Paulo, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz.

97:1147–1152. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pereira M, Tripathy S, Inamdar V, Ramesh

K, Bhavsar M, Date A, Iyyer R, Acchammachary A, Mehendale S and

Risbud A: Drug resistance pattern of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis in seropositive and seronegative HIV-TB patients

in Pune, India. Indian J Med Res. 121:235–239. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yew WW and Leung CC: Update in

tuberculosis 2007. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 177:479–485. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jayasena SD: Aptamers: An emerging class

of molecules that rival antibodies in diagnostics. Clin Chem.

45:1628–1650. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guthrie JW, Hamula CLA, Zhang H and Le XC:

Assays for cytokines using aptamers. Methods. 38:324–330. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ulrich H, Alves MJM and Colli W: RNA and

DNA aptamers as potential tools to prevent cell adhesion in

disease. Braz J Med Bio. 34:295–300. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Marimuthu C, Tang TH, Tominaga J, Tan SC

and Gopinath SC: Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) production in DNA

aptamer generation. Analyst. 137:1307–1315. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shimada T, Fujita N, Maeda M and Ishihama

A: Systematic search for the Cra-binding promoters using genomic

SELEX system. Genes Cells. 10:907–918. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jensen KB, Atkinson BL, Willis MC, Koch TD

and Gold L: Using in vitro selection to direct the covalent

attachment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev protein to

high-affinity RNA ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 92:12220–12224.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen F, Zhou J, Luo F, Mohammed AB and

Zhang ZL: Aptamer from whole-bacterium SELEX as new therapeutic

reagent against virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 357:743–748. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen F, Zhang XL, Zhou J, Liu S and Liu J:

Aptamer inhibits Mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37Rv) invasion

of macrophage. Mol Biol Rep. 39:2157–2162. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jagannath C, Emanuele MH and Hunter RL:

Activity of poloxamer CRL-1072 against drug-sensitive and resistant

strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and in

mice. Intern J Anti Agent. 15:55–63. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jing N and Hogan ME: Structure-activity of

tetrad-forming oligonucleotides as a potent anti-HIV therapeutic

drug. J Biol Chem. 273:34992–34999. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Blank M, Weinschenk T, Priemer M and

Schluesener H: Systematic evolution of a DNA aptamer binding to the

rat brain tumor microvessels: selective targeting of endothelial

regulatory protein pigpen. J Biol Chem. 276:16464–16468. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Cerchia L, Ducongé F, Pestourie C, Boulay

J, Aissouni Y, Gombert K, Tavitian B, de Franciscis V and Libri D:

Neutralizing aptamers from whole-cell SELEX inhibit the RET

receptor tyrosine kinase. PLoS Biol. 3:e1232005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|