Introduction

Neoplasms of the salivary glands constitute 3–10% of

all tumors of the head and neck (1), and are located in the parotid gland

in 34–86% of cases (2,3). Among parotid tumors, benign tumors

are more common than malignant ones (4,5).

Parotidectomy is commonly used in the treatment of gland tumors; it

is the first choice to treat gland tumors (5–7).

However, complications, such as Frey syndrome (8), transient or permanent facial nerve

paresis (9), cosmetic

disfigurement (10), pain and

discomfort, and subsequent xerostomia, can reduce the quality of

life of patients after parotidectomy (11). Among these complications, Frey

syndrome has the highest incidence, from 11 to 95% (12–14).

Frey syndrome was first described by Łucja (Lucie)

Frey in 1923 (15,16). Andre Thomas in 1927 and later Ford

and Woodhall in 1938 postulated the theory of aberrant regeneration

of the sectioned parasympathetic fibers that regrow to innervate

the vessels and sweat glands of the skin overlying the parotid to

explain the symptoms (15,17). Although Frey syndrome is not

life-threatening, the surveys show that Frey syndrome and concave

facial deformity are identified as the most serious self-perceived

sequelae with significant potential negative social and

psychological implications, which result in discomfort worsening

with time (7,11,12,18,19).

Thus, the goals of parotidectomy are to remove the primary tumor,

prevent severe functional loss, avoid cosmetic defects, and

particularly to prevent Frey syndrome.

The therapeutic and preventive methods for Frey

syndrome can be subdivided into surgical and non-surgical

modalities. Non-surgical techniques used to prevent Frey syndrome

include drugs; the most common is a local injection of botulinum

toxin. Yet, this has many side effects, including mild and

temporary muscle weakness and pain at the injection site, easy

recrudescence, and the procedure also frequently affects the

quantity and quality of salivary flow (20,21).

The major surgical techniques include implantation

of a ‘barrier’, including autogenous vascularized tissue [such as

the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap (22), temporoparietal fascia rotational

flap (23) and the superficial

muscular aponeurotic system (24)], non-vascularized tissue [such as

fascia lata (25) and dermis fat

grafts (26)], and synthetic

biomaterials [such as expanded polytef (27)]. However, these surgical management

options are limited by at least one of the following factors: i)

the need for a second operation (with its associated potential

morbidity), ii) the need for an additional donor site, iii)

prolonged period of time under general anesthesia, iv) insufficient

amount of tissue to cover the wound surface completely, v)

inability to reduce the incidence of Frey syndrome (28), and vi) the higher incidence of

wound infection, rejection reaction or other postoperative

complications (29).

A ‘barrier’ that is able to demonstrate efficacy

with regard to preventing Frey syndrome, while at the same time

eliminating the disadvantages mentioned above would be prefered and

is now being considered. AlloDerm®, in addition to

serving as a nerve barrier, may serve as an effective soft tissue

augmentation device in the head and neck region (30,31).

Since it undergoes fibrous tissue ingrowth, has extensive sources,

convenient manufacturing, efficient industrialization and virtually

no side effects, it is considered as an ideal barrier in the field

of oral health to date (32).

The first published study on the utilization of

AlloDerm in humans was conducted by MacKinnon in 1997 (33), and it has been widely used in this

field and reported in many research articles (34–41).

It is a new type of biological material, yet its long-term side

effects are unknown. Therefore, we performed this systematic review

and meta-analysis in order to evaluate the effectiveness and safety

of AlloDerm to prevent Frey syndrome after parotidectomy.

Materials and methods

Selection of studies

A comprehensive systematic search was conducted by

two independent reviewers (X.T.Z. and M.Z.L.) in PubMed (1966 to

May 2011), Embase (1974 to May 2011), the Cochrane Library (issue

4, 2011) and the ISI Web of Knowledge databases (1994 to May 2011)

for relevant citations. In addition, we searched the reference

lists of all known primary and review articles. All identified

articles were screened for cross-references; no language

restrictions were imposed.

The search terms were combined with (‘Frey syndrome’

OR ‘Frey’s syndrome’ OR ‘gustatory sweating’ OR ‘auriculotemporal

syndrome’) AND (‘AlloDerm’ OR ‘acellular tissue patch’ OR

‘acellular dermal matrix’ OR ‘acellular dermal’ OR ‘acellular

dermis’ OR ‘Permacol’ OR ‘porcine dermal matrix’ OR ‘allograft

dermis’ OR ‘allograft dermal matrix’), then duplicated results were

removed. The remaining citations were displayed and examined.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility was determined by two independent

reviewers (X.J.T. and W.H.), with consensus from the third reviewer

(W.D.L.), on the basis of information found in the article’s title,

abstract or full text. Studies were included in the review if they

met the following criteria: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and

quasi-RCTs of all the articles, the study patients included adults

(≥18 years) who were diagnosed with parotid tumors and had received

a partial or total parotidectomy with facial nerve preservation,

AlloDerm was applied as the experimental group and a placebo

(blank) as the control group. Studies that included patients with

previous surgical procedures in the parotid area or with previous

radiotherapy were excluded. Review ariticles, commentaries,

guidelines and letters were also excluded.

Data extraction

The data were extracted by two reviewers (X.J.W and

Y.M.N.) independently. In case of discrepancies, a third reviewer

(W.D.L.) was consulted and, after agreement, a consensus was

reached. Data were extracted on publication data (the first

author’s last name, year of publication and country of population

studied), sample size, patient characteristics (mean age and sex

ratio), study design, follow-up period, outcome measures and method

of measurement. Authors were contacted by e-mail for additional

information if data was unavailable.

The primary outcome measure was the incidence of

Frey syndrome (objective or subjective). Secondary outcomes

included facial contour, adverse events (wound infection and

rejection), other postoperative complications (seroma or sialocele,

salivary fistula and facial nerve paralysis) that were noted when

they were reported in the studies.

Quality assessment

We assessed the study quality using the Cochrane

Handbook’s evalution tool for assessing the risk of bias (42) and the Jadad scoring system

(43). It was also conducted by

two independent reviewers (X.T.Z. and M.Z.L.) and an agreement was

reached after consulting a third reviewer (Y.G.).

The Cochrane Handbook’s evalution tool included:

Sequence generation – Was the allocation sequence adequately

generated? Allocation concealment – Was allocation adequately

concealed? Blinding – Was knowledge of the allocated intervention

adequately blinded during the study? Blinding of participants and

personnel? Blinding of outcome assessors? Incomplete outcome data –

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? Selective

outcome reporting – Were reports of the study free of suggestion of

selective outcome reporting? Other sources of bias – Was the study

apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk

of bias?

The Jadad scoring system included: Was the study

described as randomized? Was the method used to generate the

sequence of randomization described and appropriate? Was the study

described as double-blind? Was the method of double-blinding

described and appropriate? Was there a description of withdrawals

and dropouts?

This is a five-point scale, with low-quality studies

having a score of ≤2 and high-quality studies a score of at least

3.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed in accordance with the Cochrane

Handbook (42). Intervention

effects were expressed with relative risks (RRs) and associated 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data and mean

differences (MDs) and 95% CIs for continuous data, respectively.

Heterogeneity among studies was informally assessed by visual

inspection of forest plots, and formally estimated using the

Chi-square test and I2 test (both P>0.05 and

I2<50% indicated there was no evidence of

heterogeneity between the pooled studies) (44). The fixed-effects model was first

used for meta-analyses; if there was heterogeneity, the

random-effects model was used. Publication bias was tested from

separate funnel plots (when the number of included studies was ≥9).

Symmetry of and outlying results on, the funnel plots implied lack

of bias, whereas asymmetry would imply that the results were

subject to reporting or publication bias (45). All statistical analyses were

performed using Review Manager (version 5.0.2; The Cochrane

Collaboration). Description analysis was performed when the

quantitative data could not be pooled. The data were entered into

Review Manager by X.T.Z., and M.N.Y. checked data entry.

Results

Characteristics and quality of the

included studies

A database search yielded 25 publications, of which

both of the reviewers considered 14 to be potentially eligible. We

excluded 9 of the articles during the second phase of the inclusion

process, 2 were not controlled (39,41),

3 were case reports (33,40,46)

and 1 was a meta-analysis (47).

One was not done up to Frey syndrome (48) and 2 were commentaries (49,50).

The remaining 5 articles were included in the meta-analysis

(34–38). A summary of the study selection

process is presented in Fig. 1.

There were 3 studies published in English (34,36,37)

and 2 in Chinese (35,38). A total of 409 participants were

included. The sample size ranged from 20 to 168, and the follow-up

period ranged from 5 to 39 months. All of the studies had similar

eligibility criteria (Table

I).

| Table ICharacteristics and Jadad scores of

the included studies. |

Table I

Characteristics and Jadad scores of

the included studies.

| Author/(Ref.) | Year and

country | Group | No. | Mean age

(years) | Gender (M:F) | Interventions | Study period

(years) | Follow-up

(months) | Measurement | Outcomes | Jadad scores |

|---|

| Govindaraj et

al (34) | 2001 USA | E | 32 | 51.7 | 12:20 | AlloDerm | 1997–1999 | ≥6 | Subjective | Frey syndrome | 1 |

| C | 32 | 49.8 | 14:18 | Blank | Objective | Facial contour

Complications |

| Sinha et al

(36) | 2003 USA | E | 10 | ≥18 | Not reported | AlloDerm | Not reported | ≥12 | Subjective | Frey syndrome | 1 |

| C | 10 | | | Blank | Objective | Complications |

| Yu et al

(38) | 2007 China | E | 30 | 45 | Not reported | AlloDerm | 2005–2006 | 5–14 | Objective | Frey syndrome | 1 |

| C | 27 | 43 | | Blank | | |

| Ye et al

(37) | 2008 China | E | 64 | 42 | Not reported | AlloDerm | 2004–2005 | 11–27 | Subjective | Frey syndrome | 1 |

| C | 104 | | | Blank | Objective | Facial contour

Complications |

| Li et al

(35) | 2006 China | E | 50 | 40 | 20:30 | AlloDerm | 2001–2004 | 10–39 | Subjective | Frey syndrome | 3 |

| C | 50 | | 21:29 | Blank | | Complications |

There was good agreement between the reviewers in

regards to the validity assessments. All studies were clinical

controlled trials, and the methodological quality of the included

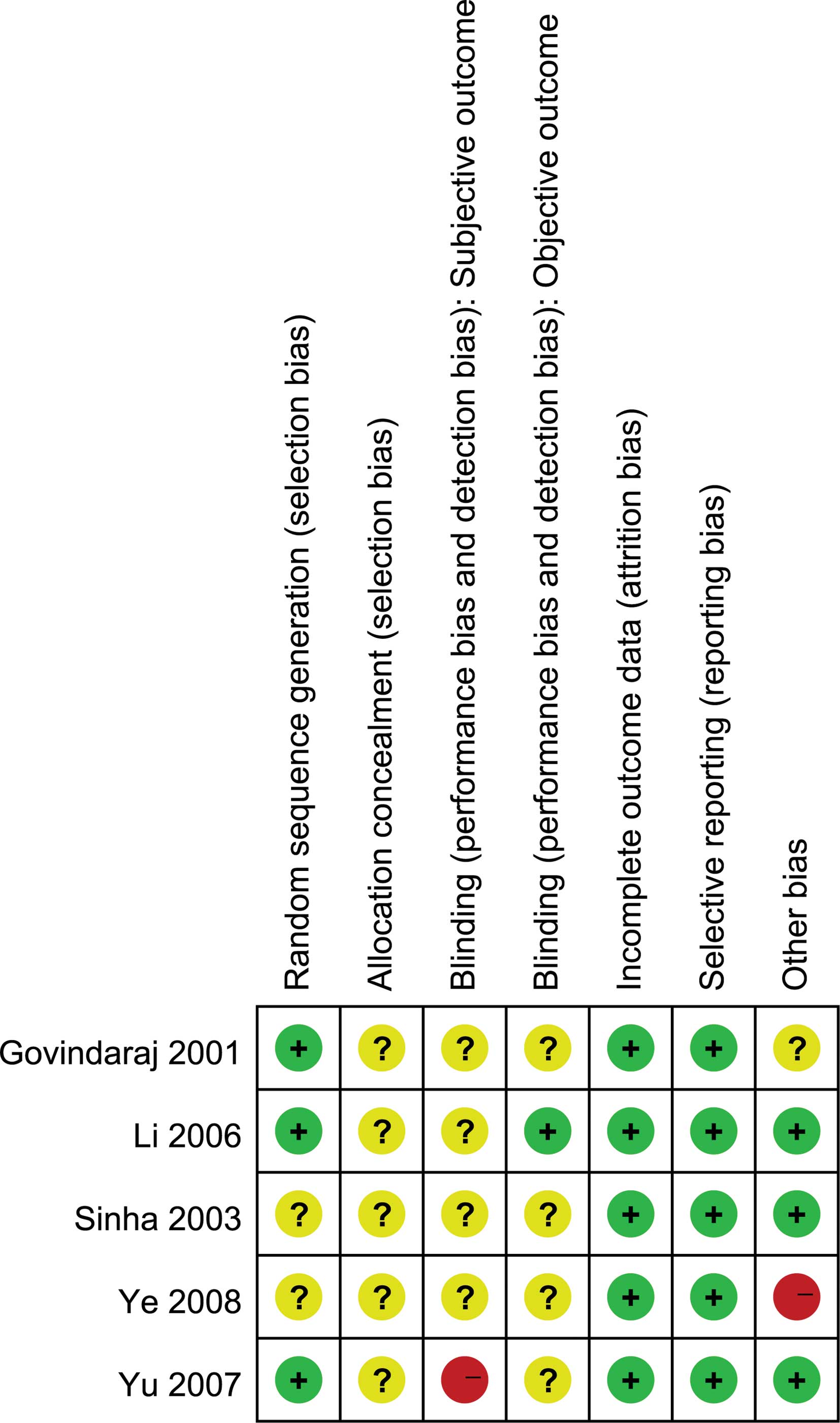

trials ranged from poor to excellent (Table I). Fig. 2 shows the risk of bias summary; the

majority had adequate patient follow-up, and the main study biases

may be caused by sample size, randomization, the procedure for

concealing the treatment allocation and blinding (as it is not

feasible to blind staff in these studies, blinding of investigators

is feasible). For example, only 1 study (35) mentioned randomization and blinding,

but did not describe how the random allocation sequence was

generated.

Frey syndrome

We extracted data for the incidence of Frey syndrome

from the included 5 studies. Four studies reported data of the

objective incidence (34,36–38),

for which outcomes were consistent across studies (heterogeneity

P=0.49, I2=0%), so the fixed effects model was used. The

result showed that there was a significant trend toward lower

incidence in the AlloDerm group (Fig.

3; RR=0.15, 95% CI 0.08–0.30; P<0.00001).

Four studies reported data involving subjective

incidence (34–37); there was significant heterogeneity

(P=0.01, I2=71%), therefore, the random effects model

was used. The result also showed that there was a significant trend

toward lower incidence in the AlloDerm group (RR=0.16, 95% CI

0.09–0.28; P<0.00001). We explored possible causes of

heterogeneity, taking into account the imbalance of patients

between the two groups in one trial (37). When we excluded this trial from the

analysis, the heterogeneity disappeared (Fig. 4; P=0.83, I2=0%), and the

trend toward the AlloDerm group weakened (Fig. 4; RR=0.32, 95% CI 0.19–0.57;

P<0.00001).

Facial contour

Two trials reported the perception of cosmetic

appearance and facial symmetry (36,37).

They found that using AlloDerm to fill in the parotid bed resulted

in better cosmesis and restoration of good soft tissue contour at

the surgical site (symmetrical, with fine scars), while the scars

of the control patients were noticeable, locally depressed and with

wrinkled skin.

Adverse events

Adverse events in the original studies consisted of

wound infection and rejection. Four studies reported data on wound

infection (34–37); there was no significant trend

toward increased incidence in the AlloDerm group (Fig. 5; RR=3.00, 95% CI 0.14–65.90;

P=0.49). The reason for the adverse event was streptococcus

species, not the AlloDerm (36).

Four studies reported data for rejection (34–37),

but all of them reported that there were no cases of implant

extrusion that occurred in the AlloDerm group.

Other postoperative complications

Other postoperative complications in the original

studies consisted of seroma/sialocele, saliva fistula and facial

nerve paralysis. Fig. 6 summarizes

the results.

Three studies reported data regarding

seroma/sialocele (34–36), for which outcomes were consistent

across studies (P=0.46, I2=0%). There was no significant

trend toward an increase in incidence in the AlloDerm group

(RR=1.36, 95% CI 0.66–2.80; P=0.40).

Two studies reported data regarding salivary fistula

(36,37), the result revealed that the

incidence was lower in the AlloDerm group and the difference had

statistical significance (RR=0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.66; P=0.02).

Three studies reported data concerning facial nerve

paralysis (34–36); there was no significant trend

toward a lower incidence in the AlloDerm group (RR=0.96, 95% CI

0.84–1.09; P=0.51).

Discussion

Principal findings

Our systematic review identified 5 studies that

addressed the relative impact of AlloDerm and a blank control. We

found that the use of AlloDerm was associated with significant

reductions in Frey syndrome (both subjective and objective

symptoms) after parotidectomy.

The period of onset of Frey syndrome is more than

3–6 months after surgery: 3 years (51), 8 and a half years (52) and, at present, the longest is 14

years (53) as reported in

research articles. The follow-up period ranged from 5 to 39 months

in the included studies, so we believe that the preliminary results

are reliable.

The present meta-analysis confirms that, despite

various confounding factors, AlloDerm does decrease the occurrence

of Frey syndrome after parotidectomy by 85% (objective) and 68%

(subjective). We also found a possible trend that AlloDerm may

decrease the incidences of salivary fistula and facial nerve

paralysis, and improve facial contour. Although AlloDerm has

several potential adverse effects, they are minimal compared to

Frey syndrome and other complications, and these effects are able

to be prevented or solved easily.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is more precise than previous ones

(47). Previously published

meta-analyses have focused on the preventive effect of surgical

techniques, and carried out a search only in PubMed for

English-language studies. They included many surgical techniques

(AlloDerm was one of them), yet no subgroup analysis was performed,

although heterogeneity was high. Therefore, the authors suggested

that further studies were necessary to stratify differences among

the various available techniques. Also, they did not take into

account adverse events or other complications.

Our study also has limitations. Firstly, the number

of studies contributing substantial data to the meta-analysis was

small; therefore, we could not fully assess the effects of

important clinical factors that may have influenced outcomes.

Possible problems with concealment, lack of blinding and loss of

follow-up could have introduced bias. The sample sizes were quite

few, thus we could not adequately assess effects. Finally,

potential limitations of any meta-analysis is the ‘file-drawer’

effect, in which studies with negative results may remain

unpublished, thus biasing the literature toward positive

findings.

Clinical and policy implications

Our results may have potential implications for

clinical practice and health policy. Frey syndrome is a widely

recognized sequela of parotidectomy; there exist many strategies

for both its prevention and treatment. Before the development of

AlloDerm, previous strategies were able to effectively prevent Frey

syndrome (47), but had various

disadvantages (20,21,28,29).

Our results, although based on only 5 randomized controlled trials,

indicate that it is plausible that AlloDerm delivers a clinically

significant reduction in preventing Frey syndrome, without adverse

effects. It may also reduce salivary fistula and facial nerve

paralysis, and improve facial contour.

Shuman and Bradford (54) supported the fact that surgeons are

obligated to inform patients regarding the significance of Frey

syndrome prior to surgery. Yet, to date the process of informed

consent and pre-operative decision-making has posed a potential

ethical quandary. Many studies have also come to the conclusion

that Frey syndrome interferes with the quality of life of patients

(7,11,12,18,19).

Therefore, surgeons and policy makers need to address the clinical

importance and value of the heighted focus in relation to the goals

of treatment, so that AlloDerm may meet their and their patients’

expectations.

Implications for research

The methods in trials were limited by the inability

to blind clinical staff to the method of operation, yet the

blinding of investigators to evaluate and collect outcome data is

feasible. Unfortunately, only 1 study performed blinding of

investigators (35). Therefore it

is possible that the decisions and actions of the clinicians could

have been influenced, resulting in biased estimates of treatment

effect.

We also found that AlloDerm may reduce salivary

fistula and facial nerve paralysis, and improve facial contour. As

a result, future studies should follow the CONSORT 2010 statement

(55) to design and report, in

order to provide high-quality evidence.

In conclusion, evidence from the included studies

suggests that use of AlloDerm results in decreased total incidence

of Frey syndrome. Evidence also suggests that AlloDerm improves

facial contour, may reduce salivary fistula and facial nerve

paralysis, without adverse events. Yet limited data from the

included studies is currently available to confirm this. Our study

also shows that it is unclear whether the use of AlloDerm permits

any conclusions about the incidence of other perioperative

complications. Further studies are required to establish the

optimal design and optimal outcome indicators.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the

Foundation of Taihe Hospital of Shiyan City (2011QD01 and

2011QD05), without commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

|

1

|

MH AnsariSalivary gland tumors in an

Iranian population: a retrospective study of 130 casesJ Oral

Maxillofac Surg6521872194200710.1016/j.joms.2006.11.02517954313

|

|

2

|

EA VuhahulaSalivary gland tumors in

Uganda: clinical pathological studyAfr Health

Sci41523200415126188

|

|

3

|

JA PinkstonP ColeIncidence rates of

salivary gland tumors: results from a population-based

studyOtolaryngol Head Neck

Surg120834840199910.1016/S0194-5998(99)70323-210352436

|

|

4

|

LJ LiY LiYM WenH LiuHW ZhaoClinical

analysis of salivary gland tumor cases in West China in the past 50

yearsOral Oncol44187192200817418612

|

|

5

|

FG SmiddyTreatment of mixed parotid

tumoursBr Med J1322325195610.1136/bmj.1.4962.322

|

|

6

|

YC LimSY LeeK KimConservative

parotidectomy for the treatment of parotid cancersOral

Oncol4110211027200510.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.06.00416129655

|

|

7

|

MA ClaymanSM ClaymanMB SeagleA review of

the surgical and medical treatment of Frey syndromeAnn Plast

Surg57581584200610.1097/01.sap.0000237085.59782.6517060744

|

|

8

|

A HerxheimerGustatory sweating and

pilomotionBr Med J1688689195810.1136/bmj.1.5072.68813510771

|

|

9

|

DH PateyRisk of facial paralysis after

parotidectomyBr Med

J211001102196310.1136/bmj.2.5365.110014057712

|

|

10

|

N MohyuddinSR HoffM YaoThe use of

allograft dermis implants and the facelift incision in parotid

surgeryOperative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck

Surgery20114119200910.1016/j.otot.2009.01.010

|

|

11

|

D NitzanJ KronenbergZ HorowitzQuality of

life following parotidectomy for malignant and benign diseasePlast

Reconstr

Surg11410601067200410.1097/01.PRS.0000135326.50939.C115457013

|

|

12

|

M KochJ ZenkH IroLong-term results of

morbidity after parotid gland surgery in benign

diseaseLaryngoscope120724730201010.1002/lary.2082220205175

|

|

13

|

K HarrisonI DonaldsonFrey’s syndromeJ R

Soc Med725035081979

|

|

14

|

R De BreeI van der WaalCR

LeemansManagement of Frey syndromeHead Neck297737782007

|

|

15

|

P DulguerovF MarchalC GysinFrey syndrome

before Frey: the correct

historyLaryngoscope10914711473199910.1097/00005537-199909000-0002110499057

|

|

16

|

P DulguerovF MarchalC GysinThe bullet that

hit a nerve: the history of Lucja Frey and her syndromeJ Laryngol

Otol12010872006

|

|

17

|

DH GlaisterJR HearnshawPF HeffronAW PeckDH

PateyThe mechanism of post-parotidectomy gustatory sweating (the

auriculo-temporal syndrome)Br Med

J2942946195810.1136/bmj.2.5102.94213584806

|

|

18

|

CH BaekMK ChungHS JeongQuestionnaire

evaluation of sequelae over 5 years after parotidectomy for benign

diseasesJ Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg62633638200918314403

|

|

19

|

D BeutnerC WittekindtS DinhKB HuttenbrinkO

Guntinas-LichiusImpact of lateral parotidectomy for benign tumors

on quality of lifeActa

Otolaryngol12610911095200610.1080/0001648060060673116923716

|

|

20

|

SR BomeliSC DesaiJT JohnsonRR

WalvekarManagement of salivary flow in head and neck cancer

patients – a systematic reviewOral Oncol44100010082008

|

|

21

|

CC WangCP WangPreliminary experience with

botulinum toxin type A intracutaneous injection for Frey’s

syndromeJ Chin Med Assoc68463467200516265860

|

|

22

|

K AsalA KoybasiogluE

InalSternocleidomastoid muscle flap reconstruction during

parotidectomy to prevent Frey’s syndrome and facial contour

deformityEar Nose Throat J841731762005

|

|

23

|

RY RubinsteinA RosenD LeemanFrey syndrome:

treatment with temporoparietal fascia flap interpositionArch

Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg125808811199910.1001/archotol.125.7.80810406323

|

|

24

|

R Moulton-BarrettG AllisonI

RappaportVariation’s in the use of SMAS (superficial

musculoaponeurotic system) to prevent Frey’s syndrome after

parotidectomyInt Surg811741761996

|

|

25

|

KA WallisT GibsonGustatory sweating

following parotidectomy: correction by a fascia lata graftBr J

Plast Surg316871197810.1016/0007-1226(78)90020-6623929

|

|

26

|

S ChandaranaK FungJH FranklinT KotylakDB

MaticJ YooEffect of autologous platelet adhesives on dermal fat

graft resorption following reconstruction of a superficial

parotidectomy defect: a double-blinded prospective trialHead

Neck31521530200910.1002/hed.20999

|

|

27

|

LJ ShemenExpanded polytef for

reconstructing postparotidectomy defects and preventing Frey’s

syndromeArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg1211307130919957576480

|

|

28

|

O Guntinas-LichiusB GabrielJP

KlussmannRisk of facial palsy and severe Frey’s syndrome after

conservative parotidectomy for benign disease: analysis of 610

operationsActa Otolaryngol126110411092006

|

|

29

|

P DulguerovD QuinodozG CosendaiP PilettaF

MarchalW LehmannPrevention of Frey syndrome during

parotidectomyArch Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg125833839199910.1001/archotol.125.8.83310448728

|

|

30

|

BM AchauerVM Van der KamB CelikozDG

JacobsonAugmentation of facial soft-tissue defects with Alloderm

dermal graftAnn Plast

Surg41503507199810.1097/00000637-199811000-000099827953

|

|

31

|

J ShulmanClinical evaluation of an

acellular dermal allograft for increasing the zone of attached

gingivaPract Periodontics Aesthet Dent820120819969028293

|

|

32

|

DS ThomaGI BenicM ZwahlenCH HammerleRE

JungA systematic review assessing soft tissue augmentation

techniquesClin Oral Implants Res20Suppl

4146165200910.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01784.x19663961

|

|

33

|

K WebsterEarly results using a porcine

dermal collagen implant as an interpositional barrier to prevent

recurrent Frey’s syndromeBr J Oral Maxillofac

Surg3510410619979146867

|

|

34

|

S GovindarajM CohenEM GendenPD

CostantinoML UrkenThe use of acellular dermis in the prevention of

Frey’s syndromeLaryngoscope111199319982001

|

|

35

|

DZ LiYH WuXL WangSY LiuZJ LiProspective

cohort study on prevention of Frey syndrome in parotid

surgeryZhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi4410331035200617074239

|

|

36

|

UK SinhaD SaadatCM DohertyDH RiceUse of

AlloDerm implant to prevent Frey syndrome after parotidectomyArch

Facial Plast Surg5109112200310.1001/archfaci.5.1.10912533152

|

|

37

|

WM YeHG ZhuJW ZhengUse of allogenic

acellular dermal matrix in prevention of Frey’s syndrome after

parotidectomyBr J Oral Maxillofac Surg46649652200818547692

|

|

38

|

K YuJ YangMJ LiHB MaClinical application

of acellular dermal matrix to prevent gustatory sweating

syndromeZhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi42570571200718070440

|

|

39

|

W ChenJ LiZ YangW YongjieW ZhiquanY

WangSMAS fold flap and ADM repair of the parotid bed following

removal of parotid haemangiomas via pre- and retroauricular

incisions to improve cosmetic outcome and prevent Frey’s syndromeJ

Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg61894900200818504166

|

|

40

|

MA ClaymanLZ ClaymanUse of AlloDerm as a

barrier to treat chronic Frey’s syndromeOtolaryngol Head Neck

Surg1246872001

|

|

41

|

N PapadogeorgakisV PetsinisP

ChristopoulosN MavrovouniotisC AlexandridisUse of a porcine dermal

collagen graft (Permacol) in parotid surgeryBr J Oral Maxillofac

Surg47378381200910.1016/j.bjoms.2008.09.00418963286

|

|

42

|

JPT HigginsS GreenCochrane Handbook for

Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 510 (updated March

2011)The Cochrane Collaboration2011Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org

|

|

43

|

AR JadadRA MooreD CarrollAssessing the

quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding

necessary?Control Clin

Trials17112199610.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

|

|

44

|

JP HigginsSG ThompsonQuantifying

heterogeneity in a meta-analysisStat

Med2115391558200210.1002/sim.118612111919

|

|

45

|

M EggerGD SmithBias in location and

selection of

studiesBMJ3166166199810.1136/bmj.316.7124.619451274

|

|

46

|

C MacKinnonM LovieAn alternative treatment

for Frey syndromePlast Reconstr

Surg103745746199910.1097/00006534-199902000-000769950578

|

|

47

|

JM CurryN KingD ReiterK FisherRN

HeffelfingerEA PribitkinMeta-analysis of surgical techniques for

preventing parotidectomy sequelaeArch Facial Plast

Surg11327331200910.1001/archfacial.2009.6219797095

|

|

48

|

SM SachsmanDH RiceUse of AlloDerm implant

to improve cosmesis after parotidectomyEar Nose Throat

J86512513200717915677

|

|

49

|

JC Lopez GutierrezThe SMAS fold flap and

ADM repair of the parotid bed following removal of parotid

haemangiomas via pre- and retroauricular incisions to improve

cosmetic outcome and prevent Frey’s syndromeJ Plast Reconstr

Aesthet Surg61900200818504166

|

|

50

|

JK WuThe SMAS fold flap and ADM repair of

the parotid bed following removal of parotid haemangiomas via pre-

and retroauricular incisions to improve cosmetic outcome and

prevent Frey’s syndromeJ Plast Reconstr Aesthet

Surg21889900200818504166

|

|

51

|

J RustemeyerH EufingerA BremerichThe

incidence of Frey’s syndromeJ Craniomaxillofac Surg3634372008

|

|

52

|

S MalatskeyI RabinovichM FradisM PeledFrey

syndrome – delayed clinical onset: a case reportOral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod943383402002

|

|

53

|

GI WenzelW DrafUnusually long latency

before the appearance of Frey’s syndrome after

parotidectomyHNO525545562004(In German).

|

|

54

|

AG ShumanCR BradfordEthics of Frey

syndrome: ensuring that consent is truly informedHead

Neck3211251128201010.1002/hed.2144320641103

|

|

55

|

KF SchulzDG AltmanD MoherC GroupCONSORT

2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group

randomised trialsBMJ340c332201010.1136/bmj.c33220332509

|