Introduction

Tamoxifen (TAM) is the most commonly prescribed drug

for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer (1,2). TAM

is a non-steroidal anti-estrogen which acts, at least in part, by

compete blockage of the estrogen receptor (ER) (3,4).

However, the existence of an alternative mechanism of action for

this drug is supported by the following clinical observations: i)

30% of patients with ER-negative cancer cells respond to TAM and

ii) 30% of patients with ER-positive cancer cells are not sensitive

to this anti-estrogen (5). The ER

activates transcription from classical hormone response elements,

to which the ER binds directly and from various alternative

response elements, to which the ER does not bind. ER action upon

the ovalbumin proximal promoter and the collagenase and IGF-1 genes

traces to activator of protein 1 (AP-1) sites that bind members of

the Jun/Fos family of transcription factors (6,7). ER

action upon the quinine reductase gene traces to an electrophile

response element and these have been reported to bind ATF

transcription factors, which are potential dimerization partners

with Jun (8). ER action upon the

cyclin D gene is linked to a CRE-like element that also binds

Jun/ATF (9–11). ER also enhances the activity of

promoters that are regulated by other factors.

Protein kinase C (PKC) was originally identified as

a phospholipid- and calcium-dependent protein kinase (12). PKC affects diverse cell functions

through phosphorylation of target proteins. These cell functions

involve a wide variety of fundamental physiological processes,

including signal transduction, modulation of gene expression,

proliferation and apoptosis (13–15).

Individual PKC isozymes exhibit various tissue distributions,

subcellular localizations and biochemical properties, an indication

that each member of the family plays specialized roles (14), which ultimately translates into

unique correlations with disease.

The pAP-1(PMA)-TA-luc plasmid contains the AP-1

elements, which are designed to monitor the induction of the PKC

signal transduction pathway. PKC is involved in various biochemical

processes relevant to signal transduction pathways and linked to

lipid signaling pathways (15). By

contrast, isoenzymes of PKC affect a number of biochemical

processes, including cell growth, differentiation and

transformation and plays a key role in signal transduction from

multiple extracellular receptors (16,17).

PKC activity is regulated by multiple activators and cofactors

which associate via conserved domains within the enzyme structure

(18).

In the present study, TAM was observed to inhibit

the growth of the human ER-positive breast cancer cell line, MCF-7

and ER-negative breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-435, in a

concentration-dependent manner. A previous study reported that the

observed effects of TAM and its active metabolite on the

proliferation of MDA-MB-435 cells were due to an ER-independent

mechanism (5). To verify the role

of c-Jun in TAM suppression of proliferation of the two breast

cancer cell lines, the expression of c-Jun mRNA and protein levels

were examined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

(RT-PCR) and western blot analysis. TAM treatment of MCF-7 cells

activated the transcriptional activities of AP-1(PMA), which

responds specifically to phorbol ester. Results indicate that TAM

functions as an AP-1 activator to mediate cell functions. The

inhibition rates of MCF-7 cells were found to correlate with c-Jun

expression and stimulation of TAM, whereby TAM-stimulated MCF-7

cells were positively regulated by c-Jun overexpression and

negatively regulated by c-Jun underexpression. To the best of our

knowledge, this is the first study on the correlation between c-Jun

and antiproliferation of TAM-stimulated MCF-7 cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-435, were obtained from Shanghai Cell Bank (Shanghai,

China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

(Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cell proliferation assays

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells were plated at

1×104 cells/well in 96-well plates with six replicate

wells, for 24 h in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 at

37°C). Cells were treated with various concentrations of TAM (The

First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China) for

48 h. Following this, 10 μl CCK-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto,

Japan) solution was added to each well of the plate to measure cell

proliferation. The plate was incubated for 4 h in the incubator.

Optical density (OD) was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a

microplate reader. Data were presented as the mean ± SD, which was

derived from triplicate samples of at least three independent

experiments. To examine the effect of c-Jun on inhibition rates of

TAM-stimulated MCF-7 cells, cells were transfected with

pIRES2-EGFP-c-Jun or pGPU6/GFP/Neo-c-Jun-shRNA using Lipofectamine

2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were stimulated with

TAM 48 h post-transfection.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from TAM-treated or untreated MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-435 cells was extracted by TRIzol (Gibco-BRL) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was generated from total RNA,

using M-MLV RT (MBI; Fermentas, Waltham, MA, USA). Amplification

was performed over 28 cycles consisting of 94°C for 35 sec, 53°C

for 45 sec and 72°C for 1 min. PCR products were separated by

electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium

bromide to visualize the bands. To compare differences among

samples, the relative intensity of each band was normalized against

the intensity of the GAPDH band amplified from the same sample. The

primer sequences for the genes and expected product sizes were as

follows: 5′-TGAACGGGAAGCTCACTGG-3′ (sense) and

5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3 (antisense) for GAPDH (307 bp);

5′-GCCTCAGACAGTGCCCGAGAT-3′ (sense) and

5′-GTTTAAGCTGTGCCACCTGTTCC-3′ (antisense) for c-Jun (245 bp).

Western blot analysis

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells were harvested 48 h after

TAM treatment and lysed with SDS sample buffer (80 mM Tris-HCl, 2%

SDS, 300 mM NaCl and 1.6 mM EDTA). Cell extracts were separated

using 10% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, transferred onto

nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% skimmed milk. Following

blocking, membranes were incubated with antibodies against GAPDH or

c-Jun and then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or -rabbit

IgG antibodies. Protein bands were visualized with ECL

solution.

Transient expression reporter gene

assay

MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells grown in 24-well plates

were transfected with 1 μg reporter plasmids, pAP-1(PMA)-Luc

(Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) or pAP-1-Luc, to investigate the

role of TAM in this signaling pathway. Relative luciferase activity

was normalized by co-transfection with 50 ng pRL-SV40. The cells

were then stimulated with TAM for 36 h. Cell lysates were prepared

using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison,

WI, USA) and luciferase activity was measured with GloMax 20/20.

Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

Results

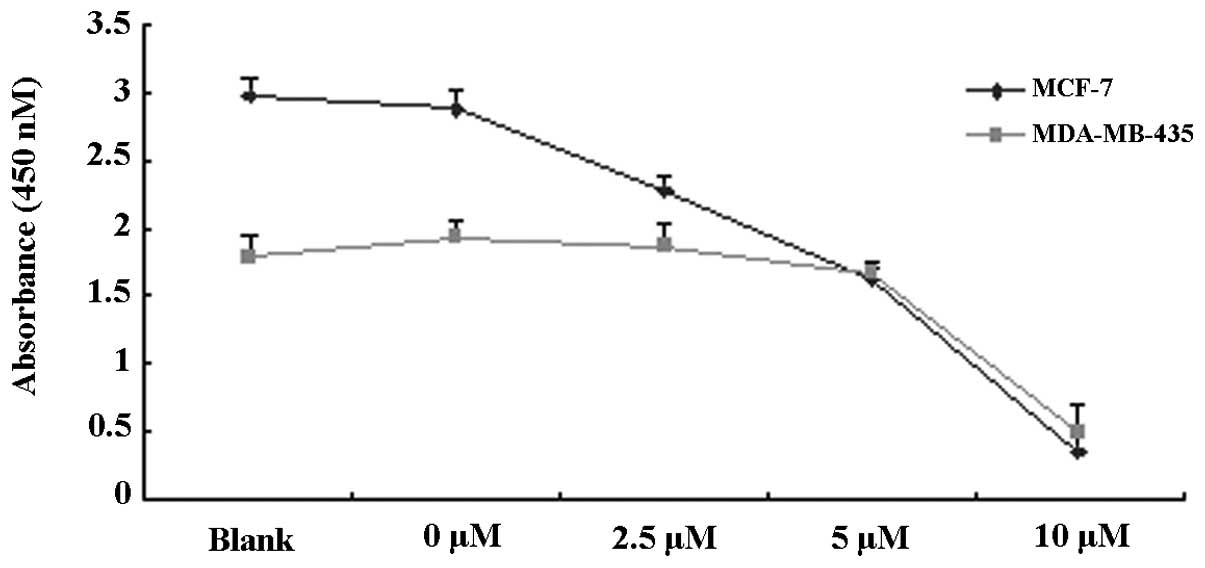

Effect of TAM on the growth of MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-435 cells in vitro

To observe the proliferation inhibitory effects of

TAM, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells were treated with various

concentrations of TAM (0, 2.5, 5 and 10 μM) for 48 h and the rate

of proliferation inhibition was detected by CCK-8 assay. As is

evident in Fig. 1A and B, TAM was

found to significantly inhibit the proliferation of MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-435 cells. The effect of inhibition was enhanced with

increased concentrations of TAM.

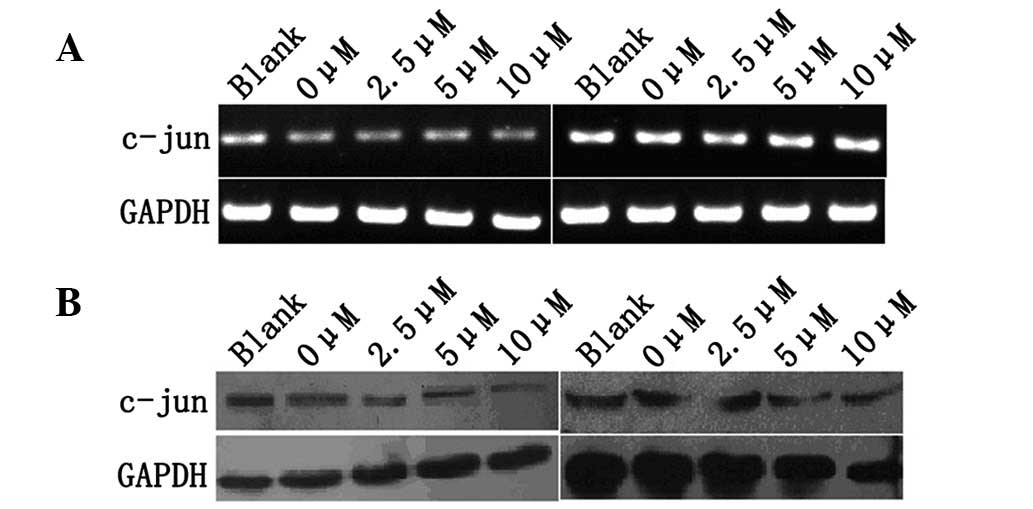

Expression of c-Jun in MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-435 cells stimulated by TAM

The effect of TAM on expression of c-Jun of MCF-7

and MDA-MB-435 cells was investigated using RT-PCR and western blot

analysis. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells were treated with various

concentrations of TAM (0, 2.5, 5 and 10 μM) for 48 h and c-Jun mRNA

and protein levels were examined by RT-PCR and western blot

analysis. No significant changes in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells were

observed (Fig. 2A and B).

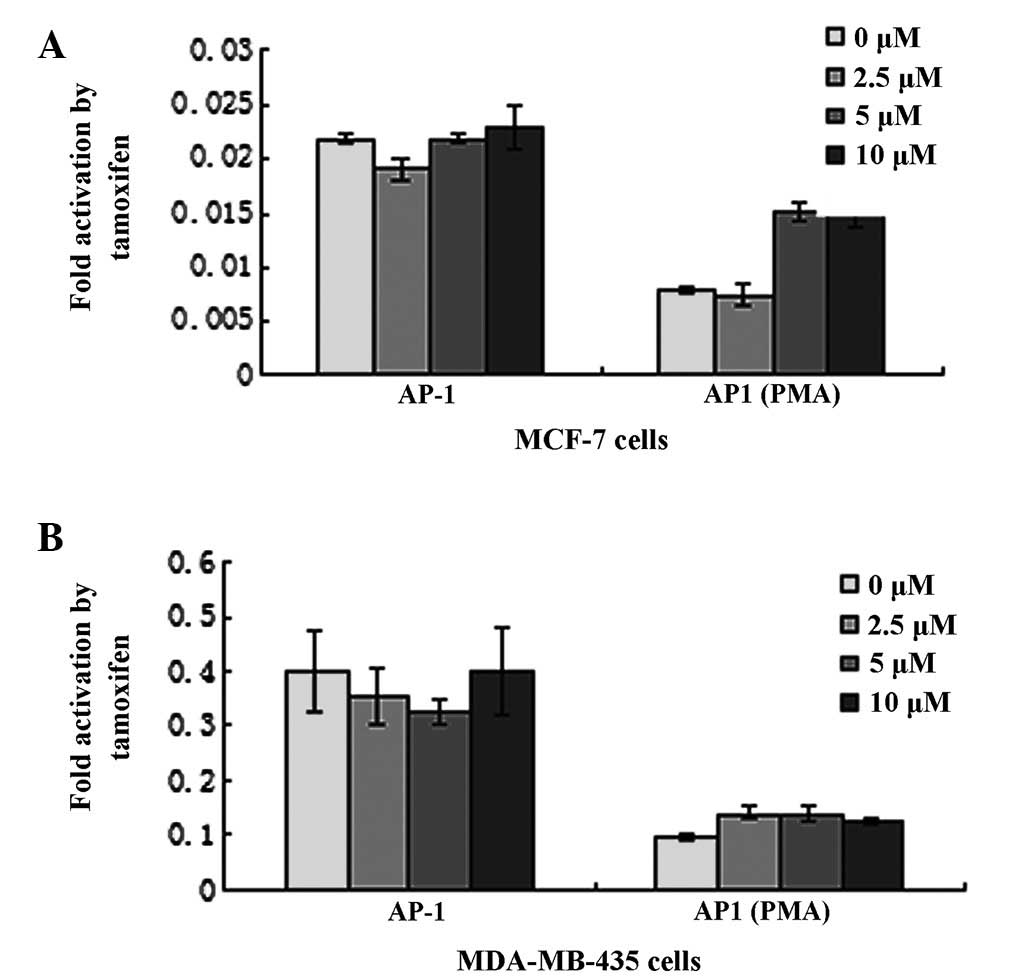

TAM activates AP-1(PMA)-mediated

transcriptional activation in MCF-7 cells

TAM is thought to function primarily by competitive

blockage of the ER. In this study, the Dual-Luciferase reporter

assay system was utilized to investigate the role of TAM on

signaling pathways, including AP-1(PMA) and AP-1. The plasmid

pAP-1(PMA)-Luc and pAP-1-Luc were transfected into MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-435 cells, which encode luciferase controlled by AP-1(PMA)

and AP-1 elements, respectively. Relative luciferase activity was

normalized by co-transfection with pRL-SV40. Cells were stimulated

with various concentrations of TAM 36 h post-transfection. In MCF-7

cells, TAM enhanced AP-1(PMA)-luciferase activity by ~200%

(Fig. 3A). In addition, TAM was

identified to induce dose-dependent activation of the AP-1(PMA)

reporter gene. However, TAM had a limited effect on AP-1. In

MDA-MB-435 cells, TAM had almost no effect on AP-1(PMA) and AP-1

(Fig. 3B).

Inhibition of proliferation of MCF-7

cells by TAM through c-Jun

To investigate a role for c-Jun in inhibition of

TAM-stimulated MCF-7 cell growth, c-Jun vectors with upregulated or

downregulated expression of c-Jun in cells were utilized. MCF-7

cells were transfected with pIRES2-EGFP-c-Jun or

pGPU6/GFP/Neo-c-Jun-shRNA and stimulated with TAM 48 h

post-transfection. CCK-8 was used to measure cell proliferation.

Inhibition rates of TAM-stimulated MCF-7 cells were found to be

positively and negatively regulated by overexpression and

underexpression of c-Jun, respectively (Fig. 4A and B). These results indicate

that c-Jun mediates antiproliferation signals in TAM-stimulated

MCF-7 cells and TAM-effected c-Jun may also induce a protein with

antiproliferative effects.

Discussion

Antiestrogenic drugs, including TAM, provide an

effective therapeutic agent for females with hormone-dependent

cancer in neoadjuvant, adjuvant and advanced disease settings

(19). However, the existence of

an alternative mechanism of action for this drug is supported by a

number of clinical observations. For example, 30% of patients with

ER-negative cancer cells respond to TAM and 30% of patients with

ER-positive cancer cells are not sensitive to this anti-estrogen

(5). Therefore, the uses of TAM

are limited. Long-term exposure to TAM is associated with

resistance and, in specific cases, with tumor growth stimulation

(20,21). The signaling pathways by which

breast tumors acquire the ability to grow in the presence of

antiestrogens, including TAM, remain poorly understood. One of the

mechanisms by which cell lines develop resistance to antiestrogens

is through the utilization of alternative signaling pathways that

support cell growth in the presence of antiestrogens. Several

signalling molecules, including PKC-δ, are known to play a major

role in E2-mediated signaling (22,23).

The PKC family of serine/threonine kinases has been

intensively studied in cancer since their identification as major

receptors for the tumor-promoting phorbol esters. The contribution

of each individual PKC isozyme to malignant transformation is only

partially understood, but it is clear that each PKC plays a

different role in cancer progression. PKC deregulation is a common

phenomenon observed in breast cancer and PKC expression and

localization are usually dynamically regulated during mammary gland

differentiation and involution. Overexpression of several PKCs has

been reported in malignant breast tissue and breast cancer cell

lines (24). Since PKC

deregulation is observed in breast cancer (25), this kinase family is a promising

target for blocking or reverting breast cancer malignancy. PKC is

known to have at least 10 phospholipid-dependent serine-threonine

kinase isoforms, one of which is PKCδ. The role of PKCδ in breast

cancer remains ambiguous and limited information is available with

regard to expression levels of PKCδ in primary tumors. Although

altered PKCδ expression does not appear to be a prerequisite for

breast cancer progression, specific previous studies, including our

own, have identified a protumorigenic role for PKCδ overexpression

in murine mammary cells via the induction of survival and

anchorage-independent growth (26). PKCδ has been reported to promote

proliferation (27) and metastasis

development (28), whereas its

depletion is sufficient to drive murine mammary cancer cells into

apoptosis (29). By contrast,

several studies have revealed that PKCδ mediates antiproliferative

responses. For example, the antimitogenic effect of inositol

hexaphosphate in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, which involves

inhibition of ERK and Akt as well as pRb hypophosphorylation, is

mediated by PKCδ (30). Crosstalk

between PKCδ and ER has also been hypothesized. Of note,

ER-positive breast cancer cell lines express high levels of PKCδ

and are associated with an improved endocrine response, whereas

ER-negative breast cancer cell lines express low PKCδ levels

(31). Moreover, PKCδ is likely to

play a crucial role in antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer

cells and has been associated with acquired resistance to TAM in

patients with breast cancer (32).

Based on these studies, we hypothesize that the PKC pathway is one

of the most important pathways associated with inhibition of MCF-7

cell proliferation by TAM. To investigate this hypothesis, the

signal transduction reporter vector was analyzed in MCF-7 cells

stimulated by TAM.

pAP-1(PMA)-TA-luc is a signal transduction reporter

vector. The vector contains multiple copies of the AP-1 enhancer,

located upstream of luciferase, that responds specifically to

phorbol ester treatment. Activating the PKC pathway by adding

phorbol esters, including PMA, results in transcription factors

binding AP-1 elements on the vector. It is designed for monitoring

the induction of the PKC signal transduction pathway. AP-1 is a

heterodimeric transcription factor that is composed of various

members of the Jun and Fos families and binds to DNA at specific

AP-1 binding sites. AP-1 transcriptional activity is increased by

phosphorylation at serine residues in the c-Jun component of AP-1.

In this study, no significant difference in c-Jun transcript and

protein levels was identified in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells

stimulated by TAM for 48 h. In addition, transcriptional reporter

gene assays indicated that TAM is an AP-1(PMA)-associated activator

(Fig. 3A). These data indicate

that TAM may function in a similar manner to PMA to modulate c-Jun

activity through the PKC pathway in MCF-7 cells. To determine the

role of c-Jun in antiproliferation of MCF-7 cells stimulated by

TAM, the correlation between inhibition rates of MCF-7 cells and

c-Jun expression and stimulation of TAM was analyzed. Inhibition

rates of TAM-stimulated MCF-7 cells were revealed to be positively

regulated by c-Jun overexpression and negatively regulated by c-Jun

underexpression.

Overall, these results indicate that TAM inhibits

proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-435 cells and has no

statistically significant effect on c-Jun transcript and protein

levels. However, TAM-stimulated antiproliferation of MCF-7 cells is

positively regulated by c-Jun through activation of the PKC

pathway.

References

|

1

|

Clarke M: Meta-analyses of adjuvant

therapies for women with early breast cancer: the Early Breast

Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group overview. Ann Oncol. 17(Suppl

10): x59–x62. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL,

Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N,

Atkins J, Daly M, Wieand S, Tan-Chiu E, Ford L and Wolmark N:

Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National

Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer

Inst. 90:1371–1388. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Katzenellenbogen BS, Fang H, Ince BA,

Pakdel F, Reese JC, Wooge CH and Wrenn CK: William L. McGuire

Memorial Symposium. Estrogen receptors: ligand discrimination and

antiestrogen action. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 27:17–26. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Katzenellenbogen BS, Montano MM, Le Goff

P, Schodin DJ, Kraus WL, Bhardwaj B and Fujimoto N: Antiestrogens:

mechanisms and actions in target cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

53:387–393. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Charlier C, Chariot A, Antoine N, Merville

MP, Gielen J and Castronovo V: Tamoxifen and its active metabolite

inhibit growth of estrogen receptor-negative MDA-MB-435 cells.

Biochem Pharmacol. 49:351–358. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Amin S, Kumar A, Nilchi L, Wright K and

Kozlowski M: Breast cancer cells proliferation is regulated by

tyrosine phosphatase SHP1 through c-jun N-terminal kinase and

cooperative induction of RFX-1 and AP-4 transcription factors. Mol

Cancer Res. 9:1112–1125. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mamay CL, Mingo-Sion AM, Wolf DM, Molina

MD and Van Den Berg CL: An inhibitory function for JNK in the

regulation of IGF-I signaling in breast cancer. Oncogene.

22:602–614. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Montano MM and Katzenellenbogen BS: The

quinone reductase gene: a unique estrogen receptor-regulated gene

that is activated by antiestrogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

94:2581–2586. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Sagara Y and Yoshida H:

Overexpression of cyclinD1 predicts for poor prognosis in estrogen

receptor-negative breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 98:415–418.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Altucci L, Addeo R, Cicatiello L, Dauvois

S, Parker MG, Truss M, Beato M, Sica V, Bresciani F and Weisz A:

17beta-Estradiol induces cyclin D1 gene transcription,

p36D1-p34cdk4 complex activation and p105Rb phosphorylation during

mitogenic stimulation of G(1)-arrested human breast cancer cells.

Oncogene. 12:2315–2324. 1996.

|

|

11

|

Fu XD, Cui YH, Lin GP and Wang TH:

Non-genomic effects of 17beta-estradiol in activation of the

ERK1/ERK2 pathway induces cell proliferation through upregulation

of cyclin D1 expression in bovine artery endothelial cells. Gynecol

Endocrinol. 23:131–137. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Urtreger AJ, Kazanietz MG and Bal de Kier

Joffe ED: Contribution of individual PKC isoforms to breast cancer

progression. IUBMB Life. 64:18–26. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Orchel A, Dzierzewicz Z, Parfiniewicz B,

Weglarz L and Wilczok T: Butyrate-induced differentiation of colon

cancer cells is PKC and JNK dependent. Dig Dis Sci. 50:490–498.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu DS, Krebs CE and Liu SJ: Proliferation

of human breast cancer cells and anti-cancer action of doxorubicin

and vinblastine are independent of PKC-alpha. J Cell Biochem.

101:517–528. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li Z, Wang N, Fang J, Huang J, Tian F, Li

C and Xie F: Role of PKC-ERK signaling in tamoxifen-induced

apoptosis and tamoxifen resistance in human breast cancer cells.

Oncol Rep. 27:1879–1886. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Stabel S and Parker PJ: Protein kinase C.

Pharmacol Ther. 51:71–95. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Newton AC: Protein kinase C: structure,

function and regulation. J Biol Chem. 270:28495–28498. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Newton AC: Regulation of protein kinase C.

Curr Opin Cell Biol. 9:161–167. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fisher B, Dignam J, Bryant J, DeCillis A,

Wickerham DL, Wolmark N, Costantino J, Redmond C, Fisher ER, Bowman

DM, Deschênes L, Dimitrov NV, Margolese RG, Robidoux A, Shibata H,

et al: Five versus more than five years of tamoxifen therapy for

breast cancer patients with negative lymph nodes and estrogen

receptor-positive tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 88:1529–1542.

1996.

|

|

20

|

Berstein LM, Zheng H, Yue W, Wang JP,

Lykkesfeldt AE, Naftolin F, Harada H, Shanabrough M and Santen RJ:

New approaches to the understanding of tamoxifen action and

resistance. Endocr Relat Cancer. 10:267–277. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Santen RJ: Long-term tamoxifen therapy:

can an antagonist become an agonist? J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

81:2027–2029. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shanmugam M, Krett NL, Maizels ET, Cutler

RE Jr, Peters CA, Smith LM, O'Brien ML, Park-Sarge OK, Rosen ST and

Hunzicker-Dunn M: Regulation of protein kinase C delta by estrogen

in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

148:109–118. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Keshamouni VG, Mattingly RR and Reddy KB:

Mechanism of 17-beta-estradiol-induced Erk1/2 activation in breast

cancer cells. A role for HER2 AND PKC-delta. J Biol Chem.

277:22558–22565. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tanaka Y, Gavrielides MV, Mitsuuchi Y,

Fujii T and Kazanietz MG: Protein kinase C promotes apoptosis in

LNCaP prostate cancer cells through activation of p38 MAPK and

inhibition of the Akt survival pathway. J Biol Chem.

278:33753–33762. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jarzabek K, Laudanski P, Dzieciol J,

Dabrowska M and Wolczynski S: Protein kinase C involvement in

proliferation and survival of breast cancer cells. Folia Histochem

Cytobiol. 40:193–194. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu JF, Crepin M, Liu JM, Barritault D and

Ledoux D: FGF-2 and TPA induce matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion

in MCF-7 cells through PKC activation of the Ras/ERK pathway.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 293:1174–1182. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Grossoni VC, Falbo KB, Kazanietz MG, de

Kier Joffe ED and Urtreger AJ: Protein kinase C delta enhances

proliferation and survival of murine mammary cells. Mol Carcinog.

46:381–390. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kiley SC, Clark KJ, Duddy SK, Welch DR and

Jaken S: Increased protein kinase C delta in mammary tumor cells:

relationship to transformation and metastatic progression.

Oncogene. 18:6748–6757. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lonne GK, Masoumi KC, Lennartsson J and

Larsson C: Protein kinase Cdelta supports survival of MDA-MB-231

breast cancer cells by suppressing the ERK1/2 pathway. J Biol Chem.

284:33456–33465. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Vucenik I, Ramakrishna G, Tantivejkul K,

Anderson LM and Ramljak D: Inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) blocks

proliferation of human breast cancer cells through a

PKCdelta-dependent increase in p27Kip1 and decrease in

retinoblastoma protein (pRb) phosphorylation. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 91:35–45. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Assender JW, Gee JM, Lewis I, Ellis IO,

Robertson JF and Nicholson RI: Protein kinase C isoform expression

as a predictor of disease outcome on endocrine therapy in breast

cancer. J Clin Pathol. 60:1216–1221. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Nabha SM, Glaros S, Hong M, Lykkesfeldt

AE, Schiff R, Osborne K and Reddy KB: Upregulation of PKC-delta

contributes to antiestrogen resistance in mammary tumor cells.

Oncogene. 24:3166–3176. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|