Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) leads to cardiomyocyte

loss and scar formation. Damaged myocytes in infarcted tissues

undergo progressive replacement by cardiac fibroblasts (CFBs) to

form scar tissue that causes a remodeling of the left ventricle

(LV). Consequently, cell-based therapeutic strategies for

myocardial repair have recently attracted considerable interest,

emerging as a promising cellular therapy for ischemic heart disease

(IHD). Recently, a growing body of evidence has shown that

mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation decreases fibrosis in

the post-infarcted heart (1).

As a major cellular component of the heart, CFBs are

directly involved in collagen synthesis of the infarct zone. One

novel strategy to reduce scar formation after MI is pivotal to

inhibit CFB proliferation and collagen synthesis. It has been shown

that mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium (MSC-CM)

significantly attenuates CFB proliferation and collagen synthesis

(2).

Bone marrow-derived MSCs are multipotent progenitor

cells. They are easy to obtain and expand readily. They are also

self-renewing and capable of repairing infarcted myocardium.

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a critical component of the cardiac

mechanical stretch sensor. It not only plays an important role in

maintaining myocardial contractility and function, it is also

important in anti-apoptosis and angiogenesis. Recent studies have

shown that in rat models, ILK-MSC delivery decreased the fibrotic

heart area after MI (3). However,

the potential mechanism of ILK-MSCs after MI is not yet fully

elucidated.

Therefore, we hypothesized that ILK-MSCs attenuate

CFB proliferation and collagen synthesis through paracrine effects.

To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of ILK-MSC-CM

on CFB proliferation and gene expression of cytokines. We implanted

ILK-MSC-CM into infarcted hearts and analyzed the cardiac

morphological and functional changes in the implanted and injured

hearts.

Materials and methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing, China (DTH ERBA

66.01/026D/2010).

Preparation and adenoviral transduction

of MSCs

MSCs were isolated from the bone marrow of

Sprague-Dawley rats and were expanded according to previously

reported protocols (4). The cells

were suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium-low glucose

(DMEM-LG; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Fourth-passage cells were transduced with a recombinant adenoviral

vector harboring human wild-type ILKcDNA and humanized recombinant

green fluorescent protein (hrGFP). Transduction efficiency was

assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

(Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), western blotting,

real-time PCR and immunofluorescence.

Preparation of CFBs

CFBs were prepared and cultured as previously

described with minimum modification (5,6).

Treatment of CFBs with conditioned

medium

Conditioned medium was collected from a 72-h culture

of fourth-passage MSCs and ILK-modified MSCs (ILK-MSCs) and

normalized by cultured cell numbers. After removing the cell

debris, the supernatant was transferred into dedicated

ultrafiltration tubes (Amicon Ultra-PL 5; Millipore, Billerica, MA,

USA), concentrated and desalted according to the manufacturer’s

protocol.

CFBs were incubated in MSC-CM or ILK-MSC-CM for 72

h. The control group was incubated in DMEM-high glucose (DMEM-HG)

containing 5% FBS for the same period of time.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using

RNAprep pure cell kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). RNA quality was

assessed by the ratio of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. One

microgram of total RNA was used for first strand cDNA synthesis by

Reverse Transcriptase from Invitrogen. Quantitative real-time PCR

was carried out using the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system

(Applied Biosystems) with SYBR green (Applied Biosystems). All

samples were plated in 48-well plates with each well containing 1

μl cDNA for a total reaction volume of 10 μl. Reactions were

carried out at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5

sec and 60°C for 34 sec. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

(GAPDH) mRNA amplified from the same samples served as an internal

control. Primers were designed by using Primer 3 software. Primer

sequences were: ILK, forward: 5′-GATTGTGCCTATCCTTGAGAAGAT-3′ and

reverse: 5′-TAAACTTTATTGTGACAGGCGG-3′; CTGF, forward:

5′-GGCTGGAGAAGCAGAGTCGT-3′ and reverse:

5′-GATGCACTTTTTGCCCTTCTTAA-3′; α-SMA, forward:

5′-TTCGTTACTACTGCTGAGCGTGAGA-3′ and reverse:

5′-AAGGATGGCTGGAACAGGGTC-3′; Col1a1, forward:

5′-ATCAGCCCAAACCCCAAGGAGA-3′ and reverse:

5′-CGCAGGAAGGTCAGCTGGATAG-3′; Col3a1, forward:

5′-TGATGGGATCCAATGAGGGAGA-3′ and reverse:

5′-GAGTCTCATGGCCTTGCGTGTTT-3′; MMP-2, forward:

5′-GATCTGCAAGCAAGACATTGTCTT-3′ and reverse:

5′-GCCAAATAAACCGATCCTTGAA-3′; MMP-9, forward:

5′-CGCAAGCCTCTAGAGACCAC-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGGGGGATCCGTGTTTATTA-3′;

TIMP-1, forward: 5′-CTGCAACTCGGACCTGGTTATAAGG-3′ and reverse:

5′-AACGGCCCGCGATGAGAAACTCC-3′; TIMP-2, forward:

5′-ATTCCGGGAATGACATCTATGGCAAC-3′ and reverse:

5′-CTGGTACCTGTGGTTTAGGCTCTTC-3′; GAPDH, forward:

5′-GGGGTGAGGCCGGTGCTGAGTA-3′ and reverse:

5′-CATTGGGGGTAGGAACACGGAAGG-3′. Each experiment was repeated three

times.

Western blotting

To identify ILK protein expression, western blotting

was performed with rabbit antibodies against ILK. MSCs infected

with Ad-ILK-hrGFP were cultured with complete medium for 72 h.

After a brief wash with PBS, cells were lysed in 0.1% Triton-X 100,

10 mM TRIS pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, and supplemented with a protease and

phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Proteins were separated by 10%

TRIS-HCL gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad), resolved onto 0.2 μm

nitrocellulose membranes, and blocked in nonfat milk in

TRIS-buffered saline supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20.

Immunoreactivity against ILK or GAPDH was visualized with

appropriate horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated antibodies and ECL

plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents. Densitometric analysis

was performed with Abode Photoshop. The ILK signals were normalized

to signals of GAPDH. Experiments were performed in triplicate and

repeated three times.

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU)

staining

EdU staining was performed using

Click-iT® EdU Imaging kit (cat no. Cc103338; Invitrogen,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Acute myocardial infarction

Ligation of the LAD artery was performed as

previously described (7). Briefly,

animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with a

combination of xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (80 mg/kg),

endotracheally intubated, and mechanically ventilated. After a left

thoracotomy through the fifth intercostal space, the heart was

exposed, the pericardial sac was cut, and the heart exteriorized

through the space. The LAD was ligated with a 6–0 silk suture

approximately midway between the left atrium and the apex of the

heart. Successful MI was identified by blanching of the left

ventricular muscle and the presence of ST elevation on

electrocardiograms.

Prior to surgery, animals were randomized into four

groups. Accordingly, a total volume of 600 μl of MSC-CM, ILK-MSC-CM

or complete medium was injected in five different sites at the

infarct border zone (BZ) 30 min after LAD ligation. Control animals

were operated at the same way, with the exception that no injection

was performed. The chest was closed, and animals were weaned from

the ventilator and allowed to recover.

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic investigation was performed three

days and 4 weeks after MI.

Histological analysis

Animals were sacrificed, and cardiovascular tissues

were collected at the end of the experiment. Paraffin-embedded

sections (from basal, mid-region and apical blocks: 3 slices/block)

were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for morphological

examination or Masson’s trichrome staining was performed for the

assessment of interstitial fibrosis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for

Windows (version 16.0). All the data were expressed as the means ±

standard error (SE). Siginificant differences among experimental

conditions were determined by two-tailed Student’s t-tests for

two-group comparisons or ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test for

multiple-group comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Transduction of MSCs with adenoviral

vector expressing ILK

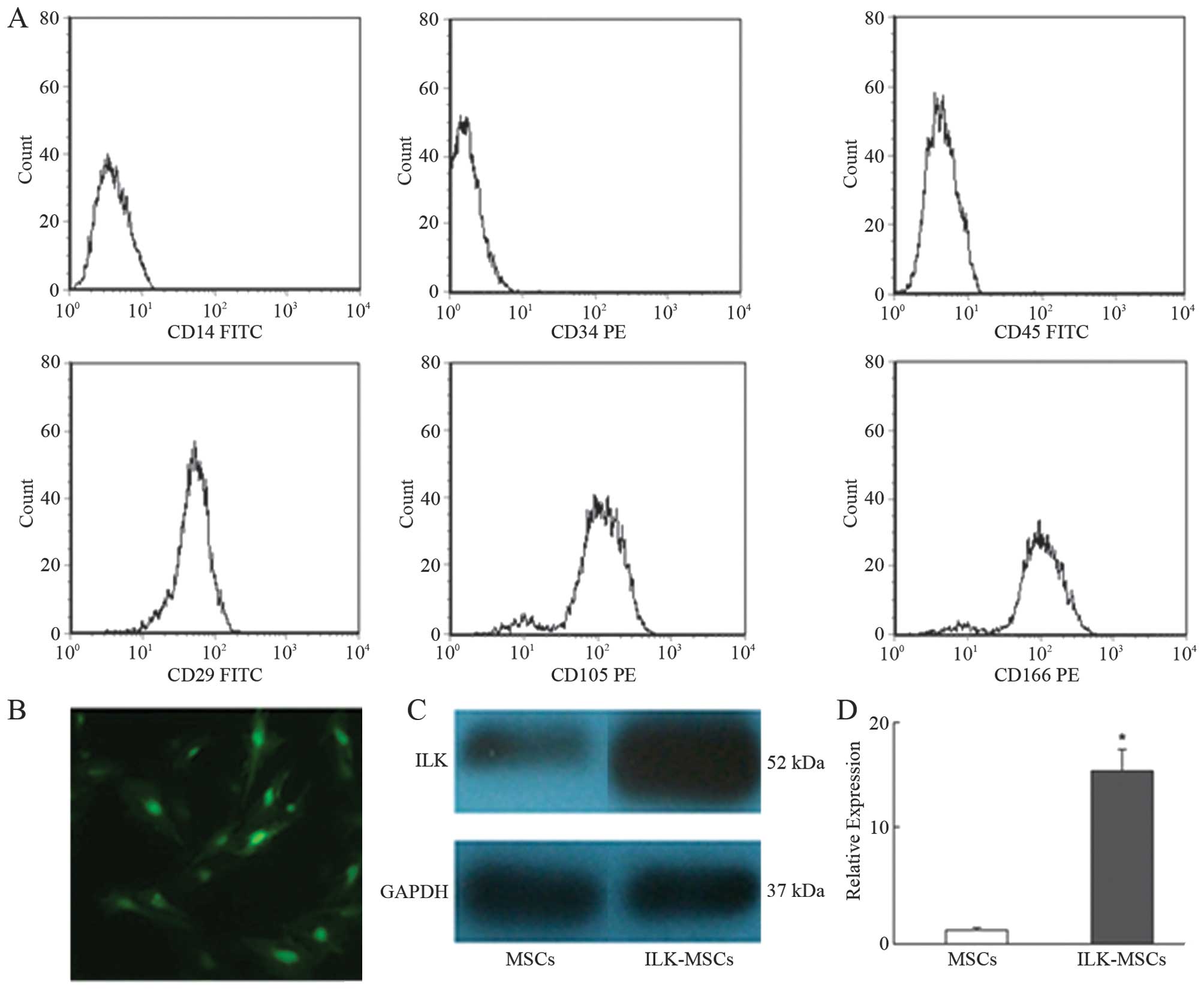

FACS analysis demonstrated that MSCs in culture

expressed low levels of CD14, CD34 and CD45, while high levels of

CD29, CD105 and CD166, in agreement with previously published data

regarding MSC cell surface markers (Fig. 1A).

The viral transduction efficacy was 85–95% in MSCs

infected with Ad-ILK-hrGFP at 200 MOI and cultured for 72 h. The

expression of hrGFP in ILK-MSCs was confirmed by photomicrograph,

qRT-PCR and western blotting (Fig.

1B-D).

Decrease of the quantity of EdU-positive

CFBs

Our results showed that the percentage of CFBs

positively stained for EdU was significantly decreased in both

MSC-CM and ILK-MSC-CM groups. The relative number of EdU-positive

cells was 41±2, 29±4 and 22±3% for the control, MSC-CM and

ILK-MSC-CM groups, respectively. The relative number of

EdU-positive cells showed a ~30 and 46% decrease in the MSC-CM and

ILK-MSC-CM group compared to the control group. In addition, the

ILK-MSC-CM group showed a ~25% decrease in the percentage of

EdU-positive cells compared to the MSC-CM group (Fig. 2A and B).

| Figure 2Effects of ILK-MSC-CM on CFB

proliferation and gene expression of cytokines. (A) Representative

imaging showing that the ILK-MSC-CM group contained fewer

EdU-positive cells than the MSC-CM and control groups. EdU (red),

Hoechst 33342 (blue). Original magnification, ×200. (B)

Quantification of EdU-positive CFBs from 10 fields of view. Data

are represented as the number of EdU-positive cells relative to the

total number of cells. Real-time PCR for (C) Col1a1, (D) Col3a1,

(E) MMP-2, (F) MMP-9, (G) TIMP-1, (H) TIMP-2, (I) α-SMA, (J) CTGF

gene expression of CFBs after 72 h of culture in the indicated

medium. Values are the means ± SE. *P<0.05 vs. SM;

#P<0.05 vs. MSC-CM. Each group n=3. ILK,

integrin-linked kinase; MSC-CM, mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned

medium; SM, standard medium; CFB, cardiac fibroblasts. |

Effect of conditioned medium on cytokine

gene expression

The results demonstrated that gene expression of

Col1a1, Col3a1, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, α-SMA and CTGF was significantly

downregulated when CFBs were cultured in conditioned medium

compared to standard medium. However, MMP-2 and MMP-9 gene

expression in CFBs incubated with conditioned medium was

significantly upregulated. The TIMP-1, TIMP-2, α-SMA and CTGF gene

expression levels of CFBs were significantly lower in the

ILK-MSC-CM-treated compared to the MSC-CM-treated cells. ILK-MSC-CM

reduced Col3a1 to a level lower compared to MSC-CM. ILK-MSC-CM

significantly upregulated MMP-2 expression, while it downregulated

MMP-9 expression compared to MSC-CM (Fig. 2C-F and H-J).

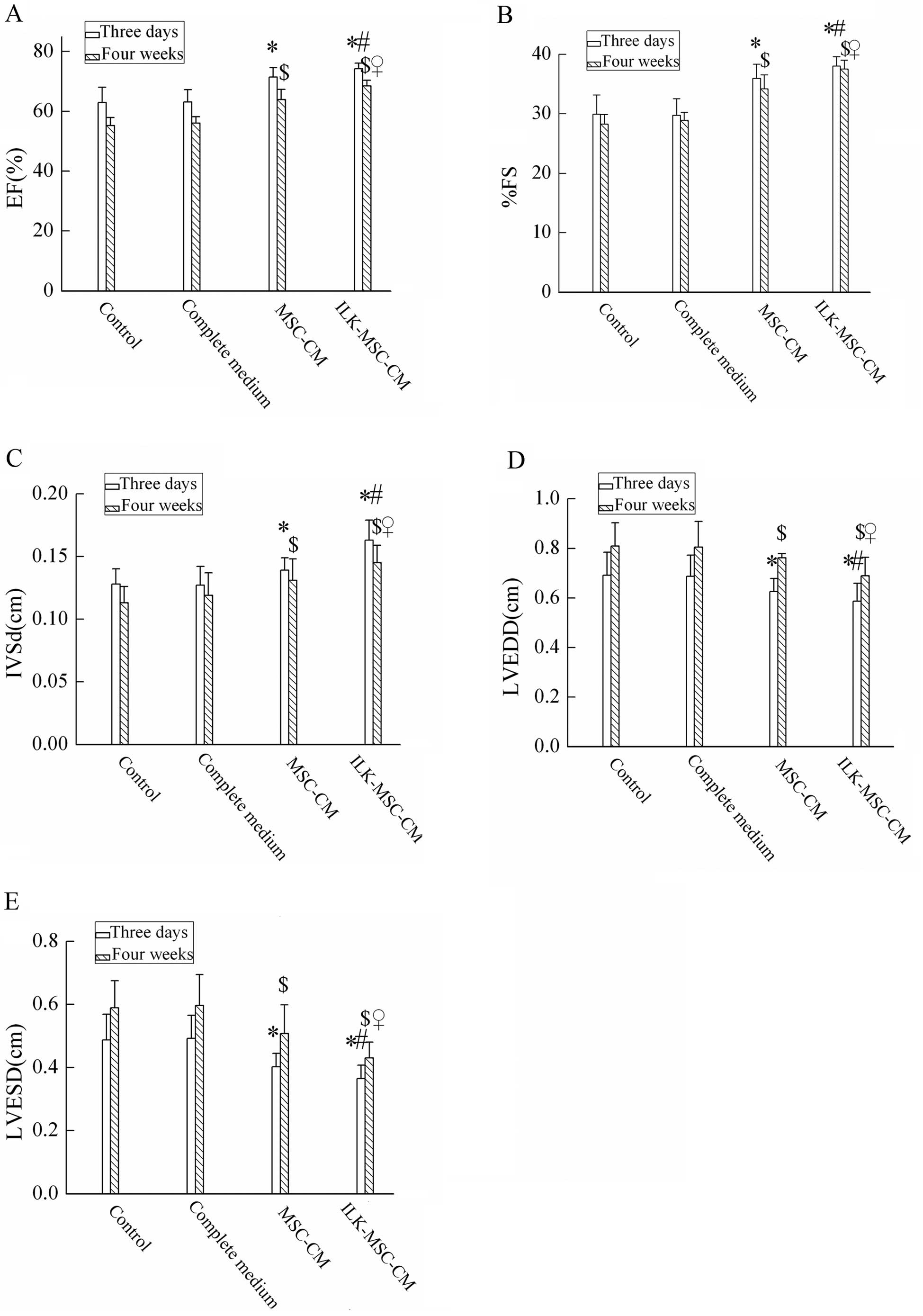

Cardiac function as detected by

echocardiography

After the ligation of the LAD artery, the MI model

detected by echocardiography was successfully established. Three

days and 4 weeks after MI, LV ejection fraction (EF), percent LV

fractional shortening (%FS), and interventricular septal thickness

in diastole (IVSd) demonstrated significant improvement in the

ILK-MSC-CM group compared to the control, complete medium and

MSC-CM groups (Fig. 3A-C). In

parallel with this, LV end-systolic dimension (LVESD) and LV

end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD) were lower in the ILK-MSC-CM group

(Fig. 3D and E). No significant

difference in LV posterior wall thickness (LVPW) was detected.

Histological analysis

The effect of ILK-MSC-CM on myocardial injury 4

weeks after infarction was evaluated by H&E staining. The mean

infarct size in the control animals was 35±3% of the LV. Injection

of complete medium had a similar injury effect, limiting the size

of the infarct to 36±4% of the LV. However, injection of MSC-CM had

a modest protective effect, limiting the size of the infarct to

30±4% of the LV. By contrast, injection of ILK-MSC-CM significantly

limited the infarct size to 22±3% of the LV. Compared to the other

three groups, this translated into a relative reduction in the

infarct size of the ILK-MSC-CM group (Fig. 4A-D).

Reduction of interstitial fibrosis in

infarct boder zone

Masson’s trichrome staining for interstitial

fibrosis in the infarct BZ in the four experimental groups is shown

in Fig. 4E. Collagen volume

fractions (CVF) were significantly lower in the ILK-MSC-CM group

compared to the other three groups. Consequently, ILK-MSC-CM

treatment significantly inhibits collagen synthesis and suppresses

collagen deposition, resulting in a reduction in ventricular

remodeling (Fig. 4F).

Discussion

In this present study, we studied the paracrine

effects of ILK-MSCs on CFBs in vitro and in vivo. The

following were demonstrated: i) MSC-CM and ILK-MSC-CM significantly

inhibited CFB proliferation, while ILK-MSC-CM further suppressed

CFB proliferation compared to MSC-CM. ii) MSC-CM and ILK-MSC-CM

distinctly inhibited type I and III collagen gene expression in

CFBs. ILK-MSC-CM further restrained type III collagen gene

expression. iii) MSC-CM and ILK-MSC-CM significantly increased

MMP-2 and MMP-9 gene expression in CFBs. iv) MSC-CM and ILK-MSC-CM

significantly decreased TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 gene expression in CFBs.

v) MSC-CM and ILK-MSC-CM decreased α-SMA and CTGF gene expression

in CFBs. ILK-MSC-CM further suppressed α-SMA and CTGF gene

expression compared to MSC-CM. (6)

More significant improvement occurred regarding the infarct area,

cardiac geometry (LVEDD, LVESD and IVSd), contractility (EF, %FS)

and pathological changes of the infarcted heart with ILK-MSC-CM

transplantation.

In the mammalian heart, normal cardiac function is

regulated by concordant and dynamic interactions of two major cell

types, cardiomyocytes and CFBs, which account for ~90% of all the

cells in the myocardium. The extracellular matrix (ECM) regulates

the structure of the heart and interactions between cellular and

non-cellular components. In the normal heart, CFBs are mainly

recognized as regulators of ECM metabolism, thereby maintaining

myocardial structure. These cells control ECM homeostasis and

produce MMPs and TIMPs to maintain a balance between the synthesis

and degradation of ECM components. CFBs also play a pivotal role in

the remodeling that occurs in the heart in response to pathological

changes, such as MI, heart failure and hypertension.

CFBs have the ability to synthesize and secrete

collagen type I and III and form a three-dimensional network around

bundles or laminae of myocytes (8). Inhibition of the collagen network

formation results in abnormally shaped hearts or rupture of the

ventricular wall. Under circumstances that accompany myocardial

remodeling, normally quiescent CFBs undergo phenotypic modulation

to myofibroblasts. In the remodeled heart, myofibroblasts become

highly proliferative and invasive, actively remodeling the cardiac

interstitium by increasing MMP secretion and collagen turnover

(9–11). CFBs, by themselves, secrete

increased amounts of growth factors and cytokines, which are able

to activate MMPs and regulate TIMPs, thereby contributing to

remodeling. In long-term heart remodeling, cumulative changes lead

to a net accumulation of collagen, cardiac fibrosis and loss of

cardiac function. Therefore, previous studies have shown that

myocardial scar tissue formation eventually leads to congestive

heart failure and malignant arrhythmias (2). In this respect, reduction of fibrosis

improves the ventricular compliance to a certain extent and delays

the process of heart failure.

Bone marrow-derived MSCs are self-renewing,

multipotent, and can differentiate into several distinct cell

types, including new cardiomyocytes. MSC transplantation has been

shown to improve cardiac function and decrease fibrosis in the

heart and other organs such as the lung, liver and kidney. Previous

studies have demonstrated that paracrine effects may contribute to

the improvement of cardiac function and scar loss following

transplantation of MSCs (12–14).

For instance, MSC-CM has been shown to significantly attenuate the

proliferation of CFBs compared to CFB-conditioned medium (2). However, the underlying mechanisms of

MSC therapy remain controversial.

ILK is a 59-kDa ankyrin-repeat containing

serine/threonine protein kinase that interacts with the cytoplasmic

domain of α1 and α3 integrins and regulates integrin-dependent

functions (15–17). ILK functions as a scaffold in

forming multiprotein complexes connecting integrins to the actin

cytoskeleton and signaling pathways. ILK activity is stimulated by

adhesion to the ECM and by growth factors in a PI3K-dependent

manner. ILK regulates multiple signaling pathways and has been

implicated in the regulation of numerous cellular processes

including proliferation, migration, cell spreading, invasion,

differentiation, transformation and survival in various cell types.

Recent evidence have shown that ILK-MSC transplantation further

improves cardiac function and decreases fibrosis in the infarcted

myocardium when compared with myocardium that has been transplanted

with MSCs alone (18). However,

there is still a lack of related experiments on whether ILK-MSCs

play an important role through paracrine mechanisms to improve

ventricular remodeling.

Many of the functional effects of CFBs are mediated

through differentiation of CFBs to myofibroblasts, cells that

express contractile proteins, including α-SMA, a myofibroblast

marker. Differentiating fibroblasts express α-SMA, indicating

acquisition of a secretory, myofibroblast phenotype, a transition

that correlates with increased secretion of profibrotic molecules

such as collagen and fibronectin (19,20).

The present study demonstrated that ILK-MSC-CM downregulates α-SMA

expression and suppresses the differentiation of CFBs to

myofibroblasts.

CTGF is a 38-kDa protein that contains 38 conserved

cysteine residues and a heparine binding domain (21). Recently, it has been reported that

CTGF promotes proliferation and ECM production in connective tissue

(22,23). This study demonstrated that

ILK-MSC-CM inhibits CTGF expression, which is beneficial to ECM

degradation.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 are two members of the MMP family, a

group of zinc-dependent endopeptidases known to hydrolyze many

components of the ECM (24). MMP-2

and MMP-9 play a fundamental role in ECM remodeling due to their

ability to initiate and continue degradation of fibrillar

collagen.

Belonging to a group of four endogenous proteins,

TIMPs firmly regulate MMP activity (25,26).

TIMPs bind to the active site of MMPs at a stoichiometric 1:1 molar

ratio with differential affinities, thereby blocking access to

their extracellular substrates. Several studies have shown that

TIMP-2 has a maximum affinity for MMP-2, whereas TIMP-1 forms a

specific complex with pro-MMP-9 (27–29).

In normal cardiac tissue, MMPs and TIMPs are co-expressed and

tightly regulated to maintain integrity of the cardiac interstitium

(30). Consequently, the MMP/TIMP

system is a crucial contributor to ECM turnover and heart failure

progression.

In the present study, it was found that the

MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio was not differentiated in MSC and ILK-MSC

groups, whereas the MMP-2/TIMP-2 ratio significantly increased in

ILK-MSC compared to the MSC group. Elevation of the MMP-2/TIMP-2

ratio was conducive to the degradation of collagen. Furthermore, it

was favorable to angiogenesis and heart function improvement

accompanied by escalation of MMP-2 and MMP-9.

In conclusion, the data presented here demonstrate

that ILK-MSCs exert paracrine anti-fibrotic effects at least in

part through inhibition of CFB proliferation and downregulation of

collagen synthesis. The overexpression of ILK is able to regulate

the partial paracrine effects of MSCs. These features of ILK-MSCs

could be beneficial for the treatment of heart failure in which

fibrotic changes are involved.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Zheng Xing

from the University of Minnesota for expert technical assistance,

and Congzhu Shi from the University of Pennsylvania for helpful

comments and suggestions.

References

|

1

|

Jaquet K, Krause KT, Denschel J, et al:

Reduction of myocardial scar size after implantation of mesenchymal

stem cells in rats: what is the mechanism? Stem Cells Dev.

14:299–309. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ohnishi S, Sumiyoshi H, Kitamura S and

Nagaya N: Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate cardiac fibroblast

proliferation and collagen synthesis through paracrine actions.

FEBS Lett. 581:3961–3966. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Song SW, Chang W, Song BW, et al:

Integrin-linked kinase is required in hypoxic mesenchymal stem

cells for strengthening cell adhesion to ischemic myocardium. Stem

Cells. 27:1358–1365. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Iwase T, Nagaya N, Fujii T, et al:

Comparison of angiogenic potency between mesenchymal stem cells and

mononuclear cells in a rat model of hindlimb ischemia. Cardiovasc

Res. 66:543–551. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen K, Chen J, Li D, Zhang X and Mehta

JL: Angiotensin II regulation of collagen type I expression in

cardiac fibroblasts: modulation by PPAR-gamma ligand pioglitazone.

Hypertension. 44:655–661. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Frangogiannis NG, Dewald O, Xia Y, et al:

Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/cc chemokine

ligand 2 in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Circulation. 115:584–592. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li W, Ma N, Ong LL, et al: Bcl-2

engineered MSCs inhibited apoptosis and improved heart function.

Stem Cells. 25:2118–2127. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Goldsmith EC, Hoffman A, Morales MO, et

al: Organization of fibroblasts in the heart. Dev Dyn. 230:787–794.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Weber KT: Fibrosis in hypertensive heart

disease: focus on cardiac fibroblasts. J Hypertens. 22:47–50. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD and Long

CS: The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial

remodeling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 45:657–687.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Camelliti P, Borg TK and Kohl P:

Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts.

Cardiovasc Res. 65:40–51. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dai W, Hale SL and Kloner RA: Role of a

paracrine action of mesenchymal stem cells in the improvement of

left ventricular function after coronary artery occlusion in rats.

Regen Med. 2:63–68. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li L, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Yu B, Xu Y and

Guan Z: Paracrine action mediate the antifibrotic effect of

transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of global heart

failure. Mol Biol Rep. 36:725–731. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xu RX, Chen X, Chen JH, Han Y and Han BM:

Mesenchymal stem cells promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro

through hypoxia-induced paracrine mechanisms. Clin Exp Pharmacol

Physiol. 36:176–180. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Attwell S, Mills J, Troussard A, Wu C and

Dedhar S: Integration of cell attachment, cytoskeletal

localization, and signaling by integrin-linked kinase (ILK),

CH-ILKBP, and the tumor suppressor PTEN. Mol Biol Cell.

14:4813–4825. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tan C, Mui A and Dedhar S: Integrin-linked

kinase regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase and

cyclooxygenase-2 expression in an NF-kappa B-dependent manner. J

Biol Chem. 277:3109–3116. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Troussard AA, McDonald PC, Wederell ED, et

al: Preferential dependence of breast cancer cells versus normal

cells on integrin-linked kinase for protein kinase B/Akt activation

and cell survival. Cancer Res. 66:393–403. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ding L, Dong L, Chen X, et al: Increased

expression of integrin-linked kinase attenuates left ventricular

remodeling and improves cardiac function after myocardial

infarction. Circulation. 120:764–773. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Gabbiani G: Evolution and clinical

implications of the myofibroblast concept. Cardiovasc Res.

38:545–548. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Petrov VV, Fagard RH and Lijnen PJ:

Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth

factor-beta 1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to

myofibroblasts. Hypertension. 39:258–263. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen MM, Lam A, Abraham JA, Schreiner GF

and Joly AH: CTGF expression is induced by TGF-beta in cardiac

fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes: A potential role in heart

fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 32:1805–1819. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Frazier K, Williams S, Kothapalli D,

Klapper H and Grotendorst GR: Stimulation of fibroblast cell

growth, matrix production, and granulation tissue formation by

connective tissue growth factor. J Invest Dermatol. 107:404–411.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Igarashi A, Okochi H, Bradham DM and

Grotendorst GR: Regulation of connective tissue growth factor gene

expression in human skin fibroblasts and during wound repair. Mol

Biol Cell. 4:637–645. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Olson MW, Gervasi DC, Mobashery S and

Fridman R: Kinetic analysis of the binding of human matrix

metalloproteinase-2 and -9 to tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

(TIMP)-1 and TIMP-2. J Biol Chem. 272:29975–29983. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Vanhoutte D, Schellings M, Pinto Y and

Heymans S: Relevance of matrix metalloproteinases and their

inhibitors after myocardial infarction: A temporal and spatial

window. Cardiovasc Res. 69:604–613. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Brew K, Dinakarpandian D and Nagase H:

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: evolution, structure and

function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1477:267–283. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Menon B, Singh M and Singh K: Matrix

metalloproteinases mediate beta-adrenergic receptor-stimulated

apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 289:C168–C176. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Goldberg GI, Marmer BL, Grant GA, Eisen

AZ, Wilhelm S and He CS: Human 72-kilodalton type IV collagenase

forms a complex with a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases

designated TIMP-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 86:8207–8211. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Goldberg GI, Strongin A, Collier IE,

Genrich LT and Marmer BL: Interaction of 92-kDa type IV collagenase

with the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases prevents

dimerization, complex formation with interstitial collagenase, and

activation of the proenzyme with stromelysin. J Biol Chem.

267:4583–4591. 1992.

|

|

30

|

Brown RD, Jones GM, Laird RE, Hudson P and

Long CS: Cytokines regulate matrix metalloproteinases and migration

in cardiac fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 362:200–205.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|