Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a type of adult

stem cell that have attracted significant attention due to their

unique properties. The first source of human MSCs was identified

and isolated from bone marrow (BM) (1). The BMMSCs showed capacity for

self-renewal and multipotent differentiation. The potential uses of

MSCs have been studied extensively in vitro and in animal

models (2–4). MSCs are hypothesized to have a high

potential for use in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

(5,6). However, the availability of BMMSCs is

limited due to the location of the cells. BM aspiration, or biopsy,

is an invasive surgery, and the the differentiation capacity varies

relative to the age of the donor (7). Optional MSC sources have been

identified, including adipose tissue (8), umbilical cord blood (9) and peripheral blood (10) and Wharton’s jelly (WJ) (11). The most noteworthy source of MSCs

is the perinatally-derived stem cells i.e., stem cells from the

placenta (PL), amniotic fluid and umbilical cord (UC). These stem

cells have a number of advantages, including their ability to be

easily obtained, a low immunogenicity and lack of ethical concerns

(12). MSCs may be isolated and

cultured from the UC, PL and WJ (13).

Coronary heart disease is the third leading cause of

mortality worldwide. A number of risk factors have been revealed to

play a role in the pathogenesis of this disease, including smoking,

obesity, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. The main mechanism

is the blockage of blood flow through the heart leading to

myocardial infarction (the death of cardiac muscle cells). Cell

therapy is one of a number of therapeutic methods developed to

improve the quality of life of patients suffering from heart

problems. Various cell types have been studied extensively to

determine the most effective outcome. Adult stem cells are one of

the candidates for cell therapy. MSCs are the best option due to

three important properties; multilineage differentiation, possible

autologous sources and their immunoregulatory role. The

transdifferentiation of MSCs has been studied extensively and it is

widely accepted that MSCs are multipotent. The role of MSC

differentiation into cardiomyocyte-like cells has been demonstrated

in animal models and in vitro studies (14–16).

The present study analyzed the cardiomyocyte differentiation

ability of MSCs from perinatal sources in comparison with

BMMSCs.

Materials and methods

Perinatal cell culture

The present study was approved by the Siriraj

Institution Review Board (SIRB). Human UCs and PLs were collected

from full-term deliveries and immersed in sterile

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin under sterile conditions. The

WJ, PLs and UCs were stored and processed separately. The samples

were washed twice using PBS prior to their preparation into

2–3-cm2 sections. Perinatal tissues were collected in 15

ml centrifugal tubes containing PBS and then washed twice under

centrifugation at 984 × g for 5 min. The pellets from the washing

procedure were digested using 0.5% trypsin-EDTA at 37°C for 30 min

and placed in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks in Dulbecco’s

modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin

and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The tissues were incubated under 5%

CO2 until MSC outgrowth occurred from the explant. The

complete medium was changed twice a week. Subpassaging was

performed using 0.5% trypsin-EDTA to expand the quantity of cells

used in the experiment.

BMMSCs

BM aspirations were obtained from healthy donors

following written informed consent. The BM aspiration was collected

in 5,000 IU sodium heparin and diluted by PBS at a 1:1 ratio prior

to the isolation of mononuclear cells. Following the method of

Boyum (17), the cell suspension

was layered on Ficoll-Hypaque at a 1:1 ratio followed by

centrifugation at 984 × g for 30 min. Mononuclear cells were

harvested from the interphase layer into new centrifugal tubes for

2 cycles of washing. The cells were seeded in T25 flasks using DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml

streptomycin. The culture supernatant was removed 5–7 days later

and the adherent cells were maintained at 37°C with 5%

CO2. The BMMSCs from passages 2–5 were used in this

study.

MSC characterization

Criteria

The cells from the BM and perinatal sources were

characterized as MSCs based on the following criteria: plastic

adherence, positive and negative specific cell surface markers and

multi-potential differentiation (13).

MSC surface markers

The cell surface markers for the MSCs were examined

using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur™, Becton-Dickinson,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The immunophenotype of the MSCs was

characterized using the following mouse monoclonal antibodies:

cluster of differentiation CD34-PE, CD45-FITC, CD73-PE (all

purchased from BD Pharmingen, San Diago, CA, USA), CD90-FITC,

CD105-FITC and CD106-PE (all purchased from AbD SeroTec, Raleigh,

NC, USA). The MSCs between passages 2 and 5 were harvested using

0.5% trypsin-EDTA. A 5×105 cell suspension (50 μl) was

incubated at 4°C for 30 min in the dark with mouse anti-human

antibodies. Following incubation, the cells were washed twice with

cold PBS and centrifuged at 984 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cells

were then fixed with 300 μl 1% paraformaldehyde prior to analysis

by a flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson).

Osteogenic and adipogenic

differentiation of MSCs

The MSCs from passages 2–5 were cultured in Advance

STEM Osteogenic Differentiation medium (OsteoDiff) for osteoblast

differentiation (Hyclone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT, USA) and

Advance STEM Adipogenic Differentiation medium (AdipoDiff; Hyclone

Laboratories) for adipocyte differentiation. The MSC cells were

seeded at a density of 1×105 cells/ml and maintained in

each differentiation medium. The media were changed twice a week.

The differentiated conditioned MSCs were maintained for 3 weeks, at

which time their osteogenic and adipogenic properties were

evaluated using immunocytochemical staining with alkaline

phosphatase and Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

In vitro treatment with

5-azacytidine

The MSCs obtained from the BM, UC, PL and WJ during

passages 2–5 were used in this experiment. The MSCs were seeded at

densities of 1×105 cells in DMEM supplemented with 10%

FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin for 24 h. The

treatment group was treated with 10 μM 5-azacytidine

(Sigma-Aldrich) in complete medium for 24 h subsequent to which it

was changed into complete medium for 3 weeks. The morphology,

growth rate and viability were then observed.

RNA preparation and real-time

RT-PCR

RNA was collected from the control and

5-azacytidine-treated groups at weeks 1 and 3. The total RNA was

isolated from the cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life

Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and quantified by

spectrophotometry at 260 nm. The total RNA (2 μg) was used for

reverse transcription with the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit

(Invitrogen Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed for 40

cycles using the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems,

Bedford, MA, USA) and analyses for cardiac- and myogenic-specific

genes were performed using the following primers: α-cardiac actin

(260 bp), sense 5′-TCTATGAGGGCTACGCTTTG-3′ and antisense

5′-GCCAATAGTGATGACTTGGC-3′; Troponin T (TnT; 225 bp), sense

5′-AGAGCGGAAAAGTGGGAAGA-3′ and antisense

5′-CTGGTTATCGTTGATCCTGT-3′; Nk×2.5 (136 bp), sense

5′-CTGCCGCCGCCAACAAC -3′ and antisense 5′-CGCGGGTCCCTTCCCTACCA-3′;

and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 139 bp) sense

5′-GTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTATTG-3′ and antisense

5′-CATGGGTGGAATCATATTGGAA-3′. Each cycle consisted of denaturation

at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at 60°C for 10 sec and extension at

72°C for 40 sec. The products were quantified by the comparative

Ct method. Samples were compared with the control group,

normalized against GAPDH and presented as fold change

increases.

Immunofluorescence staining

The MSCs from passages 2–5 were cultured on chamber

slides (Lab-Tek, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA) at

1×105 cells/well with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS,

100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The 10 μM

5-azacytidine treatment and control groups from days 3 and 7 were

used for immunofluorescence analysis. The cells were washed twice

with PBS prior to fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C

for 30 min. Non-specific binding was blocked using 4% bovine serum

albumin (BSA), followed by incubation with purified goat polyclonal

TnT and mouse monoclonal GATA4 primary antibodies (both Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The samples were then

washed twice with PBS and overlaid with rabbit anti-mouse FITC-

(Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and donkey anti-goat PE-conjugated

secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 30 min at

4°C in the dark. The samples were washed twice, followed by DAPI

counterstaining and mounting using ProLong Gold Antifade

(Invitrogen Life Technologies).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 11.5

(SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

The significance was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Morphology and characterization of

perinatal MSCs

The UCMSCs, PLMSCs and WJMSCs were observed to

exhibit different morphologies following tissue culture for 1 week.

There were limited morphological differences between the tissue

sources (Fig. 1A-C). The cells

continued to grow and reached confluence within week 2 of the

primary culture. Subpassages of MSCs grown in complete medium

revealed a spindle-shaped cell morphology (Fig. 1D-F). The MSCs from passages 3 and 4

were characterized for osteogenic-adipogenic differentiation

capacity and cell surface markers. Following culture of the MSCs in

adipogenic and osteogenic media for 3 weeks, cell-specific

cytochemical staining was performed. The UCMSCs, PLMSCs and WJMSCs

were positive for Oil Red O (Fig.

1G-I) and alkaline phosphatase staining (Fig. 1J-L). The MSCs were shown to be

positive for MSC surface markers CD73, CD90 and CD105 and negative

for hematopoietic cell surface markers CD34 and CD45 (Fig. 2).

| Figure 1Morphology and characterization of

perinatal MSCs. Perinatal MSCs from the tissues were observed to be

spindle-shaped; (A) UCMSCs, (B) WJMSCs and (C) PLMSCs. Following

subpassaging of all MSC sources, the morphology was

fibroblast-like; (D) UCMSCs, (E) WJMSCs and (F) PLMSCs. Following

culturing of perinatal MSCs in adipogenic medium for 3 weeks, the

cells were stained with Oil Red O and small fat droplets were

revealed in the cytoplasm; (G) UCMSCs, (H) WJMSCs and (I) PLMSCs.

Alkaline phosphatase staining was used to characterize osteogenic

differentiation and all MSC sources showed positive staining; (J)

UCMSCs, (K) WJMSCs and (L) PLMSCs (magnification, ×100). MSCs,

mesenchymal stem cells; UC, umbilical cord; PL, placenta; WJ,

Wharton’s jelly. |

Effect of 5-azacytidine on the MSCs

The UCMSCs, WJMSCs and PLMSCs from passage 3 were

used at this stage of the study. The MSCs were treated with 10 μM

5-azacytidine for 24 h and maintained in complete medium for 3

weeks. The morphology, cell number and percent viability from week

1 were observed and compared against the control group. The

viability of all the MSC sources following treatment with

5-azacytidine was 94–100% in the UCMSCs; 84–100% in the WJMSCs and

93–100% in the PLMSCs. The morphology of the treated cells revealed

similarities with the control group in all MSC sources subsequent

to being cultured for 6 days (data not shown). The cell numbers in

the 5-azacytidine-treated group were lower than those of the

control group during the initial days in all the MSC sources.

Immunofluorescence study of cardiomyocyte

markers during MSC differentiation

The UCMSCs, WJMSCs, PLMSCs and BMMSCs from passages

3–5 were used at this stage of the study. The MSCs were treated

with 10 μM 5-azacytidine for 24 h and then changed into complete

medium for 7 days. The cardiac-specific markers, GATA4 and cardiac

TnT, were examined by immunofluorescence staining. The treated and

control MSCs revealed GATA4 expression in the nucleus, green in

Fig. 3E-H. The cardiac TnT in the

cytoplasm is presented in red in Fig.

3M-P. The expression of the two markers was higher in the

treated cells compared with the control.

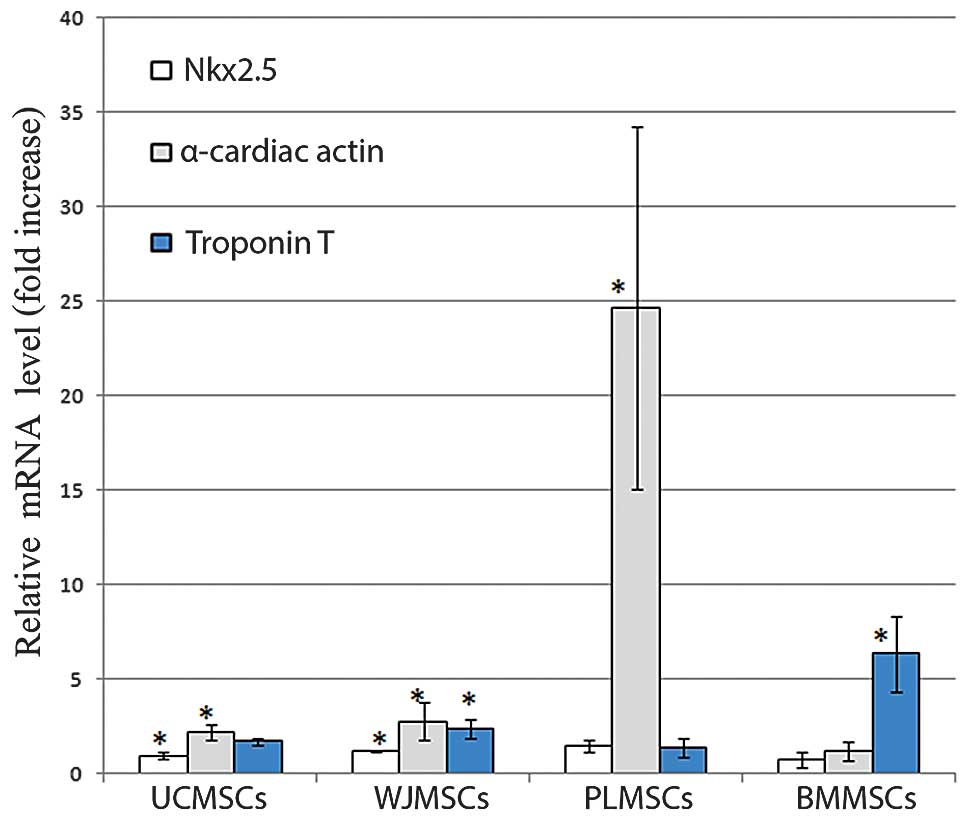

Expression of cardiomyocyte-specific

genes following treatment with 5-azacytidine

The mRNA expression of the cardiomyocyte specific

markers Nk×2.5, α-cardiac actin and cardiac TnT, was examined in

the BMMSCs, UCMSCs, PLMSCs and WJMSCs following treatment with 10

μM 5-azacytidine for 24 h and maintenance in culture for 1–3 weeks.

The quantitative analysis of the expression of the cardiac-specific

markers was performed by real-time RT-PCR and reported as a fold

increase of the control. The cardiac-specific markers showed a

higher expression level than that of the controls in the samples

treated with 5-azacytidine for 24 h and cultured for 1 week

(Fig. 4). The expression decreased

in samples maintained for 2 and 3 weeks (data not shown).

Discussion

BMMSCs have been studied extensively and a number of

promising medicinal applications have been reported. However, at

present, the clinical utilization of BMMSCs is limited due to the

invasiveness of the harvesting procedure (18). A new source of MSCs has been

identified that demonstrates a similar potential to BMMSCs

(8,9,11).

MSCs from perinatal tissue (amniotic membrane, UC and PL) were

identified as potential sources of MSCs due to their immunogenic

property, non-invasive sourcing and absence of ethical issues

(11). Moreover, the unlimited

differentiation potential of perinatal MSCs has been identified and

extensively studied (19,20).

The present study aimed to develop

cardiomyocyte-like cells from perinatal MSCs and compare them with

BMMSCs. The UC, WJ and PL were isolated and explants of each were

cultured for their residing MSCs. The MSCs were treated with the

hypomethylating agent, 5-azacytidine, and the cardiomyocyte

characteristics were evaluated. Expression of the cardiomyocyte

markers was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR and an increased

expression of Nk×2.5, TnT and α-cardiac actin was observed in the

5-azacytidine-treated MSCs compared with the controls. However, the

cardiomyocyte gene expression patterns varied depending on the

source of the MSCs. These observations may be due to variations in

the capacity and fate of each MSC source (21), which is determined by the

epigenetic state of the cells (22,23).

The effect of 5-azacytidine in the present study was

consistent with previous studies (18,24,25).

However, the mechanism of this hypomethylating agent yielded a

non-specific pattern and remains undefined. In addition, a

reduction in cardiac-specific marker expression was identified

following 5-azacytidine treatment for 2–3 weeks. The transient

expression of these markers may be a limitation of using

5-azacytidine as a differentiation initiation factor. The

combination of 5-azacytidine with other factors may be more

successful for improving the properties of

cardiomyocyte-differentiated MSCs.

The role of MSCs in the regeneration of damaged

tissue remains controversial. The mechanisms include the role of

MSCs in neoangiogenesis (26,27),

transdifferentiation (28),

anti-inflammatory responses (29)

and as a protective factor (30).

The success of transplantation may be due to various aspects that

play a concerted role in tissue regeneration. A clinical trial of

MSCs in the treatment of cardiac ischemia revealed a reduced

efficacy in the engraftment rate and functional capacity (31). The majority of studies concerning

BMMSCs have revealed that these cells are autologous and

allogeneic. The allogeneic origin of MSCs from other sources may be

optional and is particularly true of perinatal MSCs due to their

potential role in growth and neonatal development and their

availability. However, further studies are required to ensure the

proper use of these MSCs for stem cell transplantation.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the

Thailand Research Fund (no. RTA 488-0007) and the Commission on

Higher Education (no. CHERES-RG-49).

Abbreviations:

|

BM

|

bone marrow

|

|

BSA

|

bovine serum albumin

|

|

DMEM

|

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

|

|

GAPDH

|

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase

|

|

MSC

|

mesenchymal stem cell

|

|

PL

|

placenta

|

|

TnT

|

troponin T

|

|

UC

|

umbilical cord

|

|

WJ

|

Wharton’s jelly

|

References

|

1

|

Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Latsinik

NV, Panasyuk AF and Keiliss-Borok IV: Stromal cells responsible for

transferring the microenvironment of the hemopoietic tissues.

Cloning in vitro and retransplantation in vivo. Transplantation.

17:331–340. 1974. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al:

Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells.

Science. 284:143–147. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wu Y, Chen L, Scott PG and Tredget EE:

Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through

differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 25:2648–2659. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Morigi M, Introna M, Imberti B, et al:

Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells accelerate recovery of

acute renal injury and prolong survival in mice. Stem Cells.

26:2075–2082. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fu X and Li H: Mesenchymal stem cells and

skin wound repair and regeneration: possibilities and questions.

Cell Tissue Res. 335:317–321. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Richardson SM, Hoyland JA, Mobasheri R,

Csaki C, Shakibaei M and Mobasheri A: Mesenchymal stem cells in

regenerative medicine: opportunities and challenges for articular

cartilage and intervertebral disc tissue engineering. J Cell

Physiol. 222:23–32. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mueller SM and Glowacki J: Age-related

decline in the osteogenic potential of human bone marrow cells

cultured in three-dimensional collagen sponges. J Cell Biochem.

82:583–590. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bunnell BA, Flaat M, Gagliardi C, Patel B

and Ripoll C: Adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, expansion and

differentiation. Methods. 45:115–120. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lee OK, Kuo TK, Chen WM, Lee KD, Hsieh SL

and Chen TH: Isolation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from

umbilical cord blood. Blood. 103:1669–1675. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Villaron EM, Almeida J, López-Holgado N,

et al: Mesenchymal stem cells are present in peripheral blood and

can engraft after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation. Haematologica. 89:1421–1427. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang HS, Hung SC, Peng ST, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cells in the Wharton’s jelly of the human

umbilical cord. Stem Cells. 22:1330–1337. 2004.

|

|

12

|

Surbek D, Wagner A and Schoeberlein A:

Perinatal stem cell therapy. Perinatal Stem Cells. Cetrulo CL,

Cetrulo KJ and Cetrulo CL Jr: John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ:

pp. 51–60. 2009

|

|

13

|

Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al:

Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal

cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position

statement. Cytotherapy. 8:315–317. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Shim WS, Jiang S, Wong P, et al: Ex vivo

differentiation of human adult bone marrow stem cells into

cardiomyocyte-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 324:481–488.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hattan N, Kawaguchi H, ando K, et al:

Purified cardiomyocytes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

produce stable intracardiac grafts in mice. Cardiovasc Res.

65:334–344. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kruglyakov PV, Sokolova IB, Zin’kova NN,

et al: In vitro and in vivo differentiation of mesenchymal stem

cells in the cardiomyocyte direction. Bull Exp Biol Med.

142:503–506. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Boyum A: Isolation of leucocytes from

human blood. A two-phase system for removal of red cells with

methylcellulose as erythrocyte-aggregating agent. Scand J Clin Lab

Invest Suppl. 97:9–29. 1968.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xu W, Zhang X, Qian H, et al: Mesenchymal

stem cells from adult human bone marrow differentiate into a

cardiomyocyte phenotype in vitro. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

229:623–631. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsai MS, Hwang SM, Tsai YL, Cheng FC, Lee

JL and Chang YJ: Clonal amniotic fluid-derived stem cells express

characteristics of both mesenchymal and neural stem cells. Biol

Reprod. 74:545–551. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wu KH, Zhou B, Lu SH, et al: In vitro and

in vivo differentiation of human umbilical cord derived stem cells

into endothelial cells. J Cell Biochem. 100:608–616. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kadivar M, Khatami S, Mortazavi Y,

Shokrgozar MA, Taghikhani M and Soleimani M: In vitro

cardiomyogenic potential of human umbilical vein-derived

mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 340:639–647.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Benayahu D, Shefer G and Shur I: Insights

into the transcriptional and chromatin regulation of mesenchymal

stem cells in musculo-skeletal tissues. Ann Anat. 191:2–12. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Collas P: Epigenetic states in stem cells.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1790:900–905. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Martin-Rendon E, Sweeney D, Lu F,

Girdlestone J, Navarrete C and Watt SM: 5-Azacytidine-treated human

mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells derived from umbilical cord, cord

blood and bone marrow do not generate cardiomyocytes in vitro at

high frequencies. Vox Sang. 95:137–148. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang Y, Chu Y, Shen W and Dou Z: Effect

of 5-azacytidine induction duration on differentiation of human

first-trimester fetal mesenchymal stem cells towards

cardiomyocyte-like cells. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg.

9:943–946. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Nagaya N, Kangawa K, Itoh T, et al:

Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells improves cardiac function

in a rat model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation.

112:1128–1135. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Silva GV, Litovsky S, Assad JA, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into an endothelial phenotype,

enhance vascular density, and improve heart function in a canine

chronic ischemia model. Circulation. 111:150–156. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Shake JG, Gruber PJ, Baumgartner WA, et

al: Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in a swine myocardial

infarct model: engraftment and functional effects. Ann Thorac Surg.

73:1919–1926. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guo J, Lin GS, Bao CY, Hu ZM and Hu MY:

Anti-inflammation role for mesenchymal stem cells transplantation

in myocardial infarction. Inflammation. 30:97–104. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Markel TA, Wang Y, Herrmann JL, et al:

VEGF is critical for stem cell-mediated cardioprotection and a

crucial paracrine factor for defining the age threshold in adult

and neonatal stem cell function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

295:H2308–H2314. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Copland IB and Galipeau J: Death and

inflammation following somatic cell transplantation. Semin

Immunopathol. 33:535–550. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|