Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common type of

extracranial solid tumor of neuroectodermal cell origin in

children, occurring most frequently in the adrenal medulla and

sympathetic nervous system. Neuroblastoma accounts for 10% of

malignant solid tumors in children (1), with ~75% of cases occurring prior to

5 years of age. The biological characteristics of NB are diverse

and unique compared with other types of cancer of the nervous

system. In a number of infants, NB may spontaneously disappear. In

other infants, NB may differentiate into benign ganglioneuroma

following chemotherapy. However, in the majority of patients with

NB, metastases are observed at the time of diagnosis, with rapid

progression and mortality being a frequent outcome (2). There is a marked correlation between

amplification of the MYC family gene MYCN, rapid progression

of NB and poor prognosis (3). A

haploid genome, consisting of >10 copies of the MYCN

gene, is predictive of poor outcome independent of anatomic

staging, age and other clinical variables. By contrast, there is a

positive association between MYCN amplification and

malignant behavior in NB (4).

microRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous non-coding RNAs of 22 nucleotides

that regulate the expression of proteins by binding to

complementary sequences in the 3′UTR of target genes. It is well

documented that miRNAs regulate a variety of biological processes,

including cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and aging

(5,6). Accumulating evidence also indicates

that miRNAs are involved in a number of pathological conditions,

including cancer, cardiac infarction, arrhythmias, viral infection

and Alzheimer’s disease (7,8),

suggesting that miRNAs are a novel target for therapeutic

intervention. miRNA-202 (miR-202) functions as a promoter and

suppressor of tumor formation and a regulator of immune function

(9–12). The expression of miR-202 is high in

human endometrium and adipose tissue-derived stem cells, suggesting

that expression levels may be linked to cell cycle control.

Furthermore, alterations in miR-202 expression may be associated

with the formation of testicular tumors. In addition, miR-202 may

regulate the expression of the MYCN gene and thereby inhibit

the proliferation of neuroblastoma MNA Kelly cells, which generally

exhibit a high MCYN gene copy number (13). This study was designed to examine

whether MYCN is a target gene of miR-202 in the

neuroblastoma cell line LAN-5, whether miR-202 has a binding site

for the transcription factor E2F1 and to define a putative

regulatory pathway involving miR-202, MYCN and E2F1. A

dysfunctional E2F1/miR-202/MYCN signaling pathway may

contribute to malignant transformation or enhance the aggression of

neuroblastoma.

Materials and methods

Materials

LAN-5 cells were purchased from Tianjin Ke Ruijie

Biological Ltd.. (Tianjin, China), and HEK293T cells were purchased

from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology

(Shanghai, China). RPMI-1640 medium and Lipofectamine 2000 were

purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Reagents for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were

purchased from Takara Bio Inc. (Shiga, Japan). Antibodies against

E2F1 and MYCN were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO,

USA). Genome sequencing was performed by the Beijing Huada Genomics

(Shenzhen, China). Primer premier 5.0 software was used for primer

design. The synthesis of primers and the PAGE purification process

was performed by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

The mature sequence of hsa-miR-202 (5′-AGAGGUAUAGGGCAUGGGAA-3′,

MIMAT0002811) and an miRNA inhibitor sequence were obtained

obtained from miRBase (http://www.mirbase.org/cgi-bin/get_seq.pl?acc=MIMAT0002811).

The negative control sequence and negative control inhibitor

sequence were purchased from Ruibo Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.

(Shanghai, China).

Cell transfection

The experimental culture groups included: i)

untransfected LAN-5 cells (control), ii) cells transfected with

miR-202 mimics (50 nmol/l), iii) cells transfected with the miR-202

scramble nucleotide sequence (negative control or NC, 50 nmol/l)

and iv) cells transfected with an miRNA inhibitor (NI; 100 nmol/l),

a negative control for NI (NCI; 50 nmol/l). Cells in log phase

growth were seeded on 6-well culture plates (2×105

cells/well) and transfected when the cell fusion rate reached 70%.

The RNA-Lipofectamine 2000 compound was added according to the

experimental group (1 μl/well to yield 20 nmol/l miRNA). After 36

h, the transfection medium was discarded, the cells were washed

with serum-free RPMI-1640 and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented

with 10% FBS. Fluorescence microscopy was used to determine

transfection efficiency.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed using an

Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Foster City, CA,

USA). The expression level of 18S RNA was used as an internal

control for mRNAs and the U6 expression level was used as an

internal control for miRNAs. The primers used for quantitative PCR

analysis were as follows: U6 (forward, 5′-GCTTCGGCAGCACAT

ATACTAAAAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGCTTCACGAATTTGC GTGTCAT-3′), 18S

(forward, 5′-CCTGGATACCGCAGCT AGGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCGGCGCAATACGAATG CCCC-3′); miR-202 (RT primer,

5′-CTCAACTGGTGTCGTG GAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAGTTCCCAT-3′; forward,

5′-ACACTCCAGCTGGGAGAGGTATAGGGCATGG-3′ and reverse,

5′-CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA-3′) and MYCN (forward,

5′-CCTGAGCGATTCAGATGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CATAGTTGTGCTGCTGGT-3′).

The expression level was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt

method.

Western blot analysis

LAN-5 cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing a

proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Biocolor BioScience &

Technology, Shanghai, China). The protein concentration was

determined using bicinchoninic acid (Bioss, Beijing, China).

Protein was separated on 10% SDS-PAGE at 30 μg/gel lane and

electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were

incubated with a primary antibody against MYCN (rabbit polyclonal;

Cell Biotech, Tianjin, China) at 4°C overnight, washed extensively

with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS and incubated with a secondary antibody

conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000; Pharmingen, Becton

Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA) at room temperature for 3 h.

Immunolabeling was visualized using the ECL system (Amersham, UK).

Expression levels were normalized to the gel loading control and

expressed as fold changes compared with baseline (pretransfection)

values.

Luciferase reporter assay

The 3′UTR fragments of the MYCN gene were

obtained by PCR amplification and cloned separately into multiple

cloning sites of the psi-CHECK™-2 luciferase miRNA expression

reporter vector. HEK293T cells were transfected with miR-202 mimic,

miR-202 inhibitor, a control miRNA, a miRNA inhibitor or empty

plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleotide

substitution mutation analysis was performed using direct oligomer

synthesis of MYCN 3′UTR sequences. The constructs were

verified by sequencing. Luciferase activity was measured using the

dual luciferase reporter assay system kit (Promega, Madison, WI,

USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions on a Tecan M200

luminescence reader.

Rapid amplification of 5′cDNA ends

(5′RACE)

The 5′RACE measurements were conducted according to

the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Life Technologies).

Briefly, total RNA was extracted from LAN-5 cells with TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies). PCR reactions were

performed using the universal sense primer provided in the 5′RACE

kit and antisense primers (miR-202 outer, 5′-TTAGGCCAG

ATCCTCAAAGAAG-3′, miR-202 inter, ATAGGAAAAAG GAACGGCGG) specific

for the miR-202 coding sequence. The PCR product was cloned and

sequenced.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

Neuroblastoma cells were cultured in 10-cm dishes at

5×106/dish. Ice-cold PBS (10 ml) was added to each dish,

followed by panning and washing on a horizontal shaker (3×1 min).

Formaldehyde (1% in PBS) was used for crosslinking covalently

stabilized protein-DNA complexes. The ultrasonic slicing method was

used to cut DNA fragments bound to protein into 200–1,000 bp

fragments. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was collected,

added to Protein A Agarose and mixed for 1 h. A 10 μl aliquot was

reserved as the input for later use. Antibodies against E2F1 were

added to the remaining supernatant for co-immunoprecipitation and

incubated with Protein A Agarose. Following precipitation with low

salt solution and centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded and

the protein-DNA pellet separated by elution to obtain the DNA

template. The gene-specific primers were designed according to the

sequence of miR-202 (5′-GTTCTGCTGCTGCCGAGCGAG-3′ and

5′-CCTGGCTCAGCACTCTTCTCACA-3′). Quantitative PCR was performed to

measure target DNA levels in the purified DNA products.

Data analysis

The results are the averages of at least three

independent experiments from separately treated and transfected

cultures. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical

comparisons were made by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Expression of miR-202 in LAN-5

transfection groups

After the cells were transfected with the miR-202

mimic, miR-202 inhibitor or appropriated controls for 36 h, qPCR

was performed to assess miR-202 expression (Fig. 1). Expression was significantly

higher in cultures transfected with miR-202 mimic compared with

untransfected controls, while expression was significantly

inhibited (P<0.05) in the group transfected with the inhibitor

(NI group) compared with untransfected cultures or cultures

transfected with the inhibitor control transcript (NIC group).

| Figure 1The expression of miR-202 after

transfection with miR-202 mimics and miR-202 inhibitor in LAN-5

cells. *P<0.05 vs. control and NI, NC, NCI groups.

Bars: 1, control group; 2, miR-202 mimics group; 3, NI group; 4, NC

group; 5, NCI group. NC, negative control; NI, mRNA inhibitor; NCI,

negative control for NI; miR-202, microRNA-202. |

Effect of miR-202 on expression of

MYCN

After neuroblastoma cells in each group were

transfected with miR-202 mimic, miR-202 inhibitor or left

untransfected for 48 h, qPCR was performed to detect the relative

expression levels of MYCN mRNA. There was no significant difference

in MTCN mRNA expression among the miR-202 mimic group, blank

control group (untransfected) and the miRNA negative control group

(P>0.05; Fig. 2A). However,

western blot analysis of the MYCN protein revealed significant

differences among the miR-202 mimic group and the negative control

group (P<0.05) (Fig. 2B and C),

suggesting that miR-202 inhibits translation of MYCN.

| Figure 2The effects of miR-202 mimics on the

expression of MYCN. (A) The MYCN mRNA expression

levels were determined by quantitative PCR, *P>0.05

vs. control and NC group. (B) The MYCN protein expression

levels were determined by western blotting, *P<0.05

vs. control and NC group. (C) Western blot electrophoresis diagram.

Lanes: 1, control group; 2, negative group; and 3, miR-202 mimics

group. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; NC, negative control; NI,

mRNA inhibitor; NCI, negative control for NI; miR-202,

microRNA-202. |

miR-202 binds to the MYCN 3′UTR

TargetScan (human 6.2 version), a miRNA target gene

prediction software application, predicted two miR-202 binding

sites at 505 and 869 bp in the MYCN 3′UTR sequence. The

full-length sequence of the MYCN 3′UTR (910 bp) was cloned

downstream of the luciferase gene in the psiCHECK carrier to

construct the psiCHECK-2-MYCN 3′UTR carrier. LAN-5 cells

were cotransfected with the miR-202 mimic vector and vectors

carrying mutations in the MYCN 3′UTR-binding site 1 (505

bp), binding site 2 (869 bp) or both, to confirm direct binding of

miR-202 and MYCN 3′UTR. Cotransfection of LAN-5 cells with

miR-202 mimic and psiCHECK-2 MYCN 3′UTR significantly

inhibited luciferase activity (P<0.05), while transfection with

vectors carrying a mutation at binding sites 1 and 2 or both

vectors had little effect on luciferase activity, indicating that

miR-202 may directly regulate the expression of MYCN by

binding to target sites within the MYCN 3′UTR sequence

(Fig. 3).

| Figure 3The interaction between miR-202 and

MYCN was detected by the sensor reporter. (A) Comparison of

luciferase activity of plasmid-transfected cloned MYCN-3′UTR

*P>0.05 vs. control and NC. (B) The luciferase

activity comparison of plasmid-transfected cloned

mut-MYCN-3′UTR, ΔP>0.05 vs. control and NC.

(C) The target sequence for miR-202 at MYCN 3′-UTR. Bars: 1,

control; 2, miR-202 mimic; 3, NC; 4, NI and 5, NCI groups. NC,

negative control; NI, mRNA inhibitor; NCI, negative control for NI;

miR-202, microRNA-202. |

Transcription initiation site for miR-202

determined by 5′RACE assay

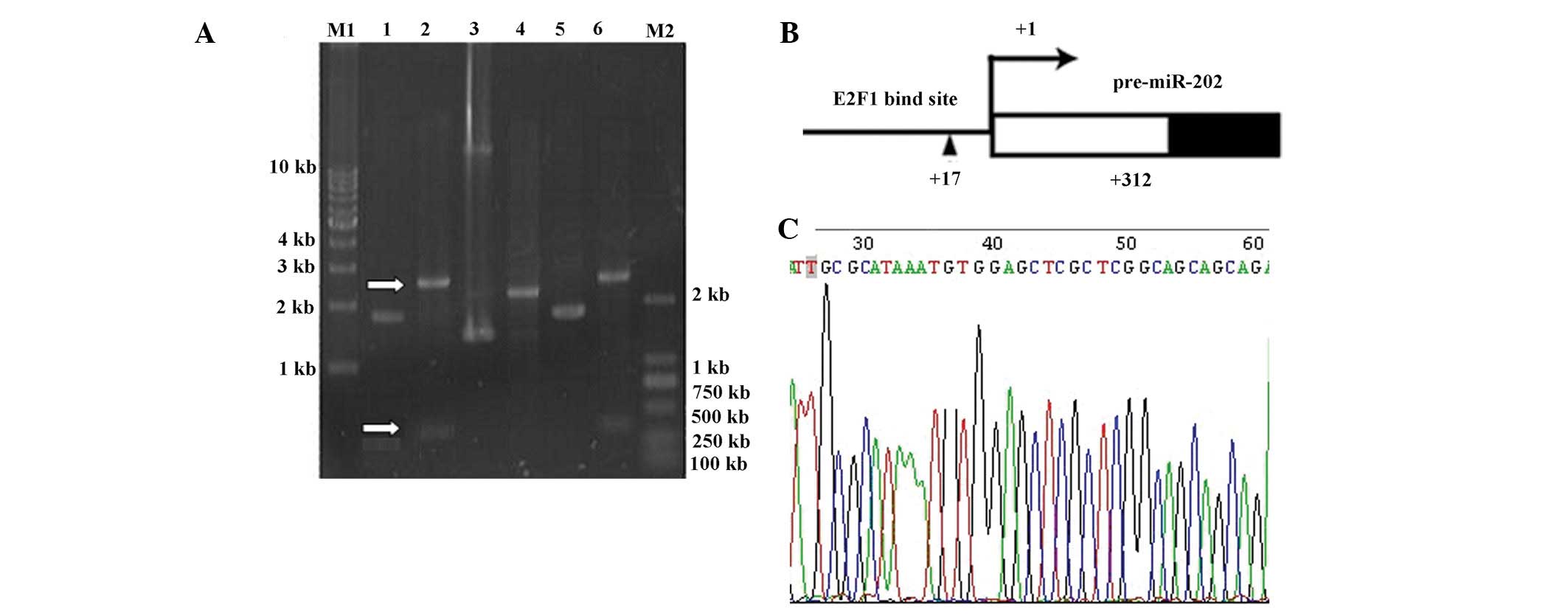

Downstream-specific primers were designed to amplify

the miR-202 gene by PCR (Fig. 4).

Specific bands were observed corresponding to miR-202-1, -2 and -3.

The miR-202-1 band was the largest at >300 bp. The primary

transcriptional copy of miR-202 was ~300 bp. The DNA fragments were

separated from the protein, recovered from the gel and cloned on

the T-vector for sequencing. Sequences of the acquired DNA

fragments were compared and the start site for transcription was

determined to be a T-vector 312 bp upstream of the miR-202

stem-loop sequence. ConSite, a transcription factor prediction

software (obtained at http://asp.ii.uib.no:8090/cgi-bin/CONSITE/consite)

predicted an E2F1 binding site +17 bp upstream of the initiation

site of miR-202.

Binding of E2F1 to the miR-202 promoter

as revealed by ChIP assay

ChIP assay was used to verify the predicted binding

sites of E2F1 +17 bp upstream of the miR-202 initiation site.

First, western blot analysis was used to detect the expression of

E2F1 in LAN-5 cells. Electrophoresis of ChIP assay produced

positive bands for the E2F1 antibody group but none for the

negative control IgG group or blank group (water). Results from

quantitative PCR showed that in lysates, including the E2F1

antibody, the relative expression of E2F1 amplified by the

E2F1ChIPF/R primer was ~18-fold higher than that in the negative

group, suggesting that the DNA was isolated using the E2F1 antibody

containing the predicted miR-202 promoter sequence. These results

indicate that E2F1 may directly bind to the promoter sequence of

miR-202 (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Amplification and overexpression of the MYCN

oncogene is frequently observed in NB. Tumors with the MYCN

amplification exhibit an invasive growth pattern, malignant

proliferation of cancer cells, a rapid increase in tumor volume,

rupture through the tumor capsule and invasion of surrounding

tissues, early systemic metastasis, poor prognosis and high

mortality (14). This study of the

molecular mechanisms of MYCN regulation by miR-202 defines a

potential regulatory pathway for control of cell proliferation and

a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of NB (15).

miRNAs regulate a variety of critical biological

processes by controlling the expression of target genes, including

genes involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis and malignant

transformation (16). miRNAs may

inhibit translation or activate mRNA degradation through

complementary pairing with a 3′UTR sequence (17). Bioinformatics prediction provides a

convenient and powerful method for identifying potential miRNA

target genes (18). TargetScan,

the standard software for prediction of miRNA target genes,

predicted two possible binding sites on the MYCN 3′UTR for

miR-202 and it was confirmed that they are indeed regulatory sites

for MYCN expression. miR-202 overexpression significantly reduced

the luciferase activity of a vector containing MYCN 3′UTR

and mutation of these potential miR-202 binding sites significantly

reduced the inhibitory effect of miR-202 on luciferase activity

(Fig. 3). Through these direct

binding sites for miR-202 on MYCN, miR-202 overexpression

may significantly reduce the expression of MYCN protein (Fig. 2B and C). However, miR-202 had no

effect on the expression of MYCN mRNA (Fig. 2A), indicating that miR-202 binding

to the 3′UTR suppresses MYCN expression at the post-transcriptional

level.

The E2F1 transcription factor is the most

significant activator governing the transition from G1 to S phase

and thus, is a key regulator of cell proliferation. The Rb/E2F

complex is a critical intermediary step in this process (19). In normal cells, Rb in the low

phosphorylation state and E2F, form a complex that inhibits the

transcription of the proto-oncogenes c-myc, c-fos and others to

inhibit cell growth. By contrast, highly phosphorylated Rb and E2F

initiates downstream gene expression and promotes cell cycle

progression (20,21). Thus, E2F plays a dual role

depending on the phosphorylation status of Rb. Previous studies

have shown that E2F activity is required for MYCN

overexpression in neuroblastoma cells (13,14).

In IMR-32 cells, overexpression of cP16INK4A may shift Rb to the

low phosphorylation state, decreasing E2F1 activity and

downregulating MYCN expression (22–24).

In the current study, E2F1 was observed to bind to the miR-202

promoter and miR-202 was observed to directly target MYCN

(Figs. 4 and 5). Previous studies demonstrated that

miR-202 directly binds to MYCN in SMS-KMN cells, thereby

downregulating MYCN expression. A potential negative

feed-forward loop may exist among E2F1, miR-202 and MYCN.

Under normal circumstances, E2F1 indirectly inhibits MYCN

activity by upregulating miR-202, thus preventing excessive

activation of MYCN by E2F1. A dynamic balance among these

three molecules may maintain normal cell growth. However, this

balance is disturbed in nascent neuroblastoma cells, with eventual

loss of MYCN regulation and malignant transformation.

Therefore, elucidation of the molecular mechanisms

regulating E2F1, miR-202 and MYCN may identify novel

molecular targets for the treatment of NB and aid in the

development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the

Guangdong Science and Technology Department Social Development

Projects (no. 2011B080702011) and the Technical New Star of

Zhujiang, Pan Yu districts, Guangzhou.

References

|

1

|

Brodeur GM: Neuroblastoma: biological

insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:203–216. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Attiyeh EF, London WB, Mossé YP, Wang Q,

Winter C, et al: Chromosome 1p and 11q deletions and outcome in

neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 353:2243–2253. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, Varmus HE

and Bishop JM: Amplification of N-myc in untreated human

neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science.

224:1121–1124. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Esquela-Kerscher A and Slack FJ: Oncomirs

- microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 6:259–269. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Lim LP, Lau NC, Weinstein EG, et al: The

microRNAs of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 17:991–1008.

2003.

|

|

6

|

Berezikov E, Guryev V, van de Belt J, et

al: Phylogenetic shadowing and computational identification of

human microRNA genes. Cell. 120:21–24. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cai B, Pan Z and Lu Y: The roles of

microRNAs in heart diseases: a novel important regulator. Curr Med

Chem. 17:407–411. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang Y, Liang Y and Lu Q: MicroRNA

epigenetic alterations: predicting biomarkers and therapeutic

targets in human diseases. Clin Genet. 74:307–315. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Couzin J: MicroRNAs make big impression in

disease after disease. Science. 319:1782–1784. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hawkins SM, Creighton CJ, Han DY, et al:

Functional microRNA involved in endometriosis. Mol Endocrinol.

25:821–832. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Novotny GW, Nielsen JE, Sonne SB, et al:

Analysis of gene expression in normal and neoplastic human testis:

new roles of RNA. Int J Androl. 30:316–326. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cho JA, Park H, Lim EH and Lee KW:

MicroRNA expression profiling in neurogenesis of adipose

tissue-derived stem cells. J Genet. 90:81–93. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Buechner J, Tømte E, Haug BH, et al:

Tumour-suppressor microRNAs let-7 and mir-101 target the

proto-oncogene MYCN and inhibit cell proliferation in

MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer. 105:296–303. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wei JS, Song YK, Durinck S, Chen QR, Cheuk

AT, et al: The MYCN oncogene is a direct target of miR-34a.

Oncogene. 27:5204–5213. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Schulte JH, Horn S, Otto T, Samans B,

Heukamp LC, et al: MYCN regulates oncogenic MicroRNAs in

neuroblastoma. Int J Cancer. 122:699–704. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: target recognition

and regulatory functions. Cell. 136:215–333. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hornstein E and Shomron N: Canalization of

development by microRNAs. Nat Genet. 38(Suppl): S20–S24. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Peterson KJ, Dietrich MR and McPeek MA:

MicroRNAs and metazoan macroevolution: insights into canalization,

complexity, and the Cambrian explosion. Bioessays. 31:736–747.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Harbour JW and Dean DC: The Rb/E2F

pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev.

14:2393–2409. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Trimarchi JM and Lees JA: Sibling rivalry

in the E2F family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 3:11–20. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rabinovich A, Jin VX, Rabinovich R, Xu X

and Farnham PJ: E2F in vivo binding specificity: comparison of

consensus versus nonconsensus binding sites. Genome Res.

18:1763–1777. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen CR, Kang Y, Siegel P and Massagué J:

E2F4/5 and p107 as Smad cofactors linking the TGFbeta receptor to

c-myc repression. Cell. 110:19–32. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lacerte A, Korah J, Roy M, Yang XJ, Lemay

S and Lebrun JJ: Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits

telomerase through SMAD3 and E2F transcription factors. Cell

Signal. 20:50–59. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Emmrich S and Pützer BM: Checks and

balances: E2F-microRNA crosstalk in cancer control. Cell Cycle.

9:2555–2567. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|