Introduction

Glycyrrhiza Radix has been used as a treatment for

thousands of years in China and its major components have been

reported to exhibit various pharmacological activities, including

anti-inflammatory (1), -obesity

(2), -viral (3), -oxidative (4) and neuroprotective (5) effects. Liquiritin (LQ), one of the

major compounds extracted from Glycyrrhiza Radix, possesses

anti-depressant-like effects, as has been indicated by

tail-suspension and forced swimming tests in mice (6). LQ also exerts neurotrophic effects,

whereby it promotes nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced neurite

outgrowth (7). The chemical

structure of LQ is shown in Fig.

1. A previous study has reported that LQ may exert

neuroprotective effects in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced

brain damage through antioxidant and anti-apoptotic mechanisms

(8). However, the neuroprotective

effect of LQ against glutamate-induced cell damage has not yet been

elucidated.

Glutamate, an important neurotransmitter in the

vertebrate nervous system, has a key role in learning and memory

(9). Glutamate-mediated

excitotoxicity occurs as part of the ischemic cascade (10) and is associated with numerous

diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, autism,

Alzheimer’s disease and certain forms of mental retardation

(9). Several signaling pathways

are involved in the regulation of glutamate-induced neurotoxicity

(11,12). Extracellular signal-regulated

kinases (ERKs) and AKT signaling pathways have been proposed to

contribute to cell differentiation, proliferation, survival and

apoptosis (13–15). Furthermore, previous studies have

demonstrated that glutamate significantly downregulates AKT and ERK

phosphorylation (16,17). A previous study has also shown that

sodium ferulate protects cortical neurons against glutamate-induced

apoptosis through phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT and ERK

signaling pathways (17).

In the present study, LQ was found to protect

differentiated PC12 (DPC12) cells against glutamate-induced reduced

cell viability, high apoptosis rates, excessive lactate

dehydrogenase (LDH) release, intracellular Ca2+ overload

and mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, LQ pretreatment was

observed to normalize the glutamate-induced alterations in pro- and

anti-apoptotic protein expression. The LQ-mediated neuroprotective

effect against glutamate-induced DPC12 cell damage was found to be

associated with ERK and AKT activation.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

PC12 cells (CRL-1721; American Type Culture

Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) were used at passages <10 and

were maintained as monolayer cultures in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle

Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% horse serum (HS; Invitrogen

Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Invitrogen Life Technologies), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml

streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2 and 95% air at 37°C. Cells were differentiated using

the addition of 20 ng/ml NGF (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in

DMEM supplemented with 1% HS, 1% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin for 48 h.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using a quantitative

colorimetric assay with MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously

(18). Briefly, PC12 cells were

seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 2×104/well

and differentiated using NGF. Cells were pretreated with 25 and 50

μM LQ (purity >98.0%; Shanghai Source Leaves Biological

Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for 3 h and co-treated with

20 mM glutamate for 24 h. In separate experiments, DPC12 cells

underwent 30 min pretreatment with 10 μM PD98059, an ERK inhibitor,

or 10 μM LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor. Cells were then treated with

25 or 50 μM LQ for 3 h, prior to exposure to 20 mM glutamate for 24

h. Treated cells were subsequently incubated with MTT solution (0.5

mg/ml) for 4 h at 37°C in the dark. The absorbance was measured

using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules,

CA, USA) at 540 nm. The viability of the treated cells was

expressed as a percentage of that of the corresponding control

cells.

Released LDH analysis

The In Vitro Toxicology Assay kit

(Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect LDH release in the culture

medium. PC12 cells were seeded onto six-well plates at a density of

1×105/well and were differentiated using NGF. DPC12

cells were pretreated with 25 and 50 μM LQ for 3 h and then

co-treated with 20 mM glutamate for 24 h. The medium in each

treatment group was collected individually. A total of 60 μl mixed

assay solution was added to 30 μl culture medium. Following

incubation at room temperature in the dark for 30 min, 10 μl 1 N

HCl was added to terminate the reaction. Absorbance was

spectrophotometrically measured at a wavelength of 490 nm. LDH

release in the treatment groups was expressed as a percentage of

the LDH released in the control group.

Flow cytometric analysis of

apoptosis

Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) double staining

was used to determine alterations in cell apoptosis. PC12 cells

were seeded onto six-well plates at a density of

1×105/well and differentiated. DPC12 cells were then

pretreated with 25 and 50 μM LQ for 3 h, prior to co-treatment with

20 mM glutamate for 24 h. Subsequent to collection, cells were

suspended in binding buffer containing 20 μg/ml Annexin

V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and 50 μg/ml PI, and incubated for 20

min at room temperature. Cell apoptosis rate was analyzed using a

flow cytometer (FC500; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA).

Intracellular Ca2+

concentration analysis

Cells were stained with Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen Life

Technologies) at a final concentration of 5 μM in order to

determine the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. PC12

cells were seeded onto confocal dishes at a density of

1×105 cells/well and differentiated. Subsequent to

pretreatment with 25 μM LQ for 3 h and co-treatment with 20 mM

glutamate for 12 h, cells were incubated with Fluo-4 AM for 30 min

at 37°C in the dark. Following three washes with phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS), the fluorescence intensity was determined using laser

scanning confocal microscopy (Axio Observer Z1; Carl Zeiss,

Oberkochen, Germany) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an

emission wavelength of 520 nm at a magnification of ×20.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

analysis

5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′

tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1; Sigma-Aldrich)

staining was used to examine alterations in Δψm. PC12 cells were

seeded onto confocal dishes at a density of 1×105

cells/well and differentiated. Subsequent to pretreatment with 25

μM LQ for 3 h and co-treatment with 20 mM glutamate for 12 h, cells

were incubated with 2 μM JC-1 at 37°C for 10 min in the dark.

Following three washes with PBS, changes in mitochondrial

fluorescence were examined using a fluorescent microscope (Axio

Observer Z1; Carl Zeiss) at a magnification of ×20. Red

fluorescence was observed in healthy cells with a high Δψm and

green fluorescence was apparent in apoptotic or unhealthy cells

with a low Δψm (19).

Western blot analysis

Treated cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation

assay buffer containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail and 2%

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich). In order to detect

cytochrome c (cyto c) release, cytoplasmic extracts

were prepared as described previously by Yang et al

(20). A total of 30 μg protein

was separated using 10–12% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically

transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (pore size, 0.45 μm; Bio

Basic, Inc., Markham, ON, Canada). The transferred membranes were

then blotted with antibodies against phosphorylated (P)-ERKs, total

(T)-ERKs, P-AKT, T-AKT, P-glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β),

T-GSK3β, B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), Bcl2-associated X protein

(Bax), cyto c and GAPDH at dilutions of 1:1,000 (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight.

Membranes were then incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 3 h at 4°C.

Chemiluminescence was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence

detection kits (GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK). The intensity of the

bands was quantified by scanning densitometry using Quantity One

4.5.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance was used to detect

statistical significance, followed by post hoc multiple comparison

tests. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. A value

of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

LQ protects DPC12 cells from

glutamate-induced apoptotic cell damage

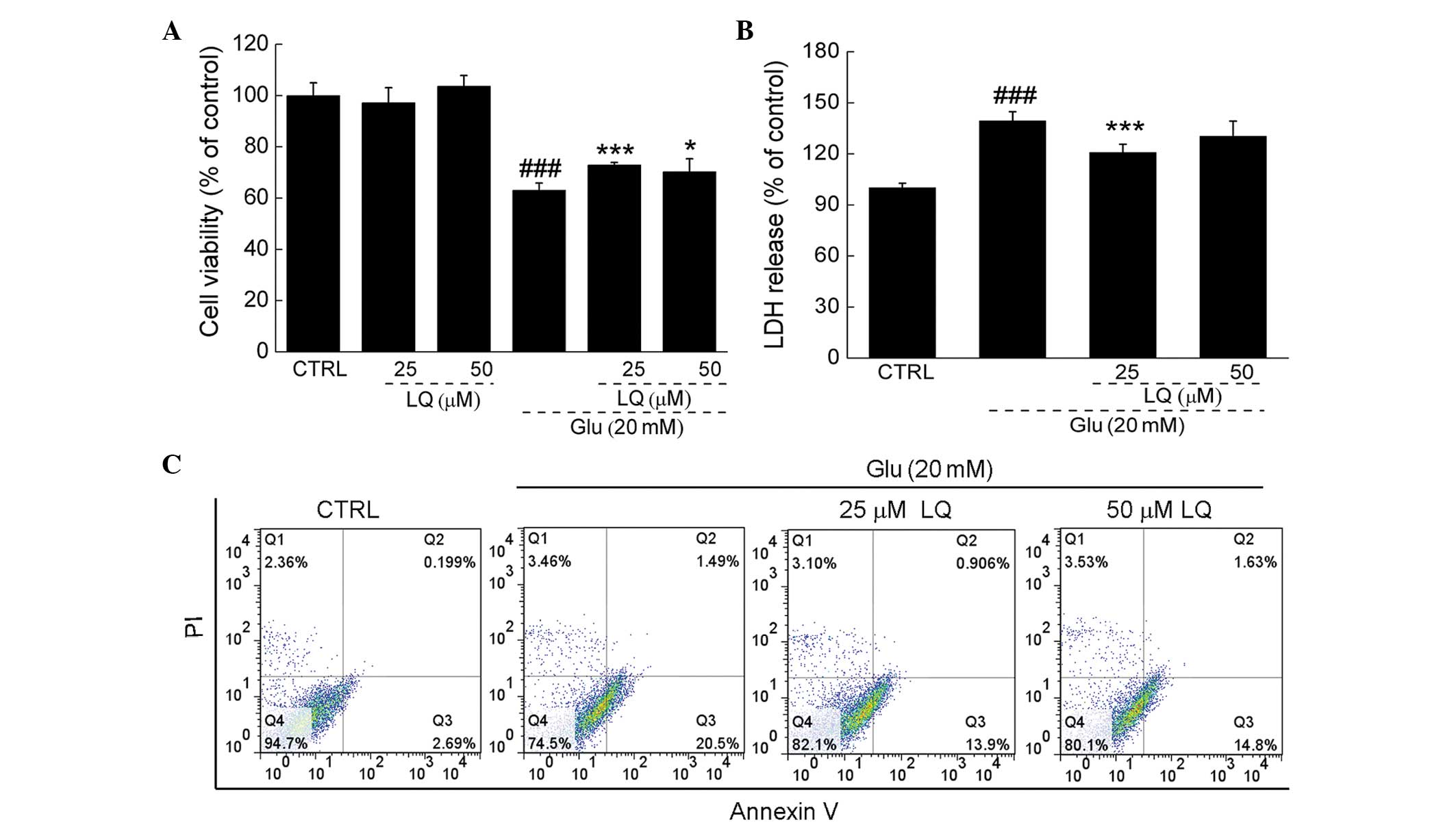

Exposure of DPC12 cells to 20 mM glutamate for 24 h

resulted in ~38% cell death; however, upon pretreatment with 25 or

50 μM LQ for 3 h, cell death was significantly reduced (71 and 74%

viability vs. 62% viability, P<0.05). Pretreatment with 25 and

50 μM LQ alone showed no effect on cell proliferation (Fig. 2A).

In DPC12 cells exposed to 20 mM glutamate, LDH

release was observed to be 39% greater than that in the control

cells (P<0.001). However, pretreatment with 25 μM LQ was found

to significantly suppress LDH release to levels 20% higher than

those in the control cells (139 vs. 120%, P<0.001) (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, flow cytometry

revealed that LQ reduced the proportion of apoptotic cells compared

with the cells solely exposed to glutamate (Fig. 2C).

LQ attenuates intracellular

Ca2+ overload and restores the dissipation of Δψm

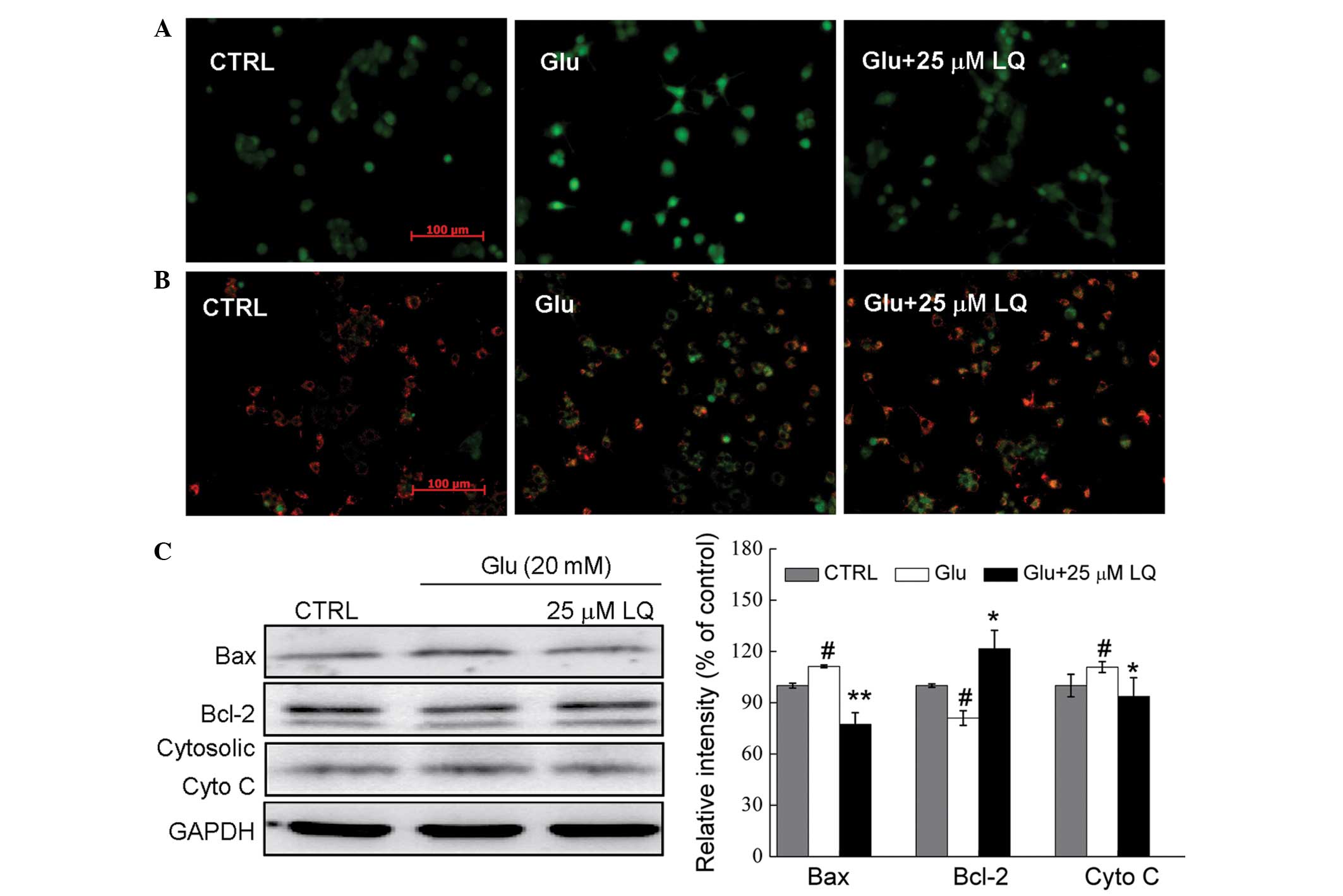

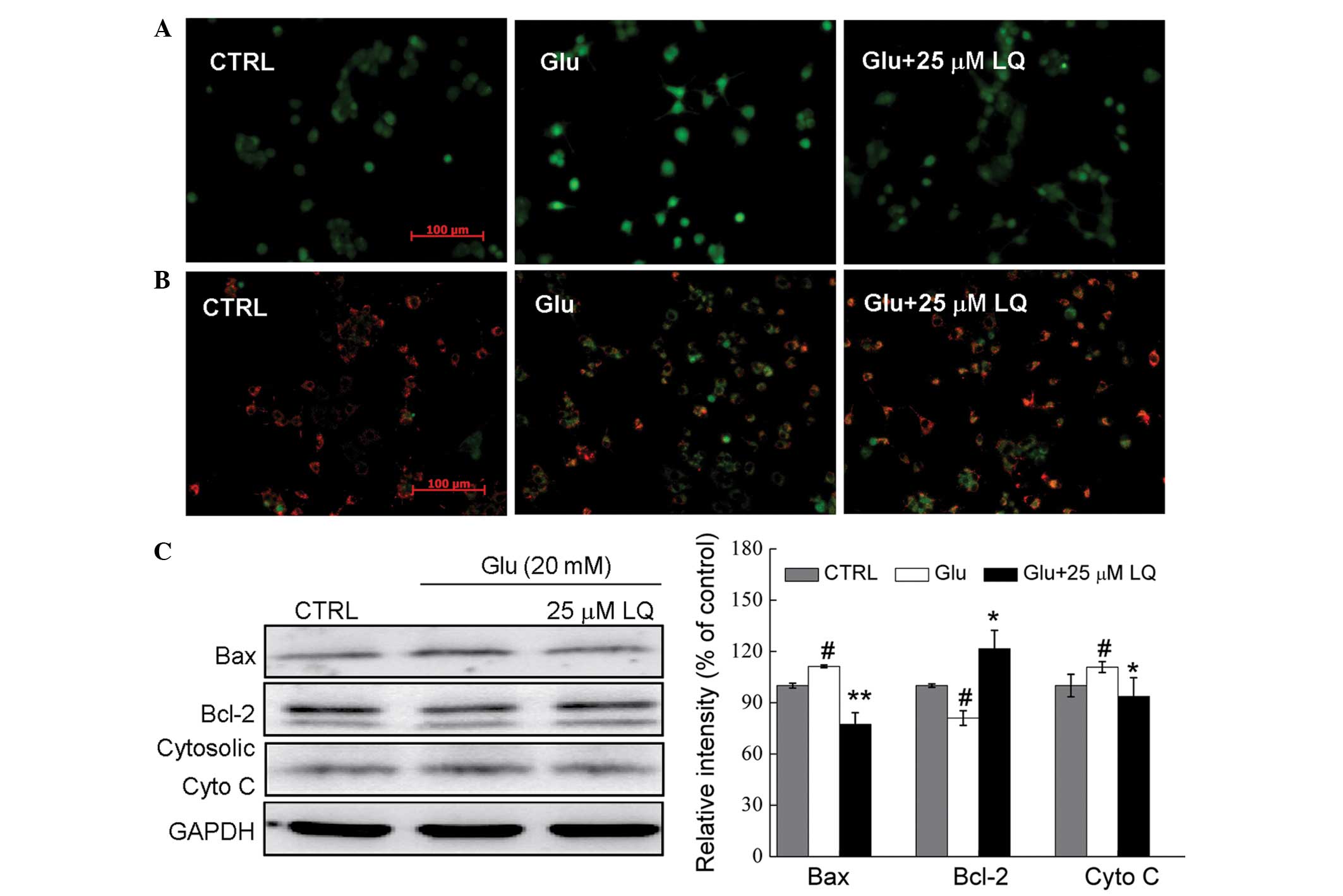

Fluo-4 AM staining was used to assess the changes in

Ca2+ concentration in DPC12 cells. In cells exposed to

20 mM glutamate for 12 h, high Ca2+ influx was observed,

as indicated by the increase in fluorescence intensity.

Pretreatment with 25 μM LQ was found to reduce this Ca2+

overload (Fig. 3A).

| Figure 3In Glu-exposed DPC12 cells, LQ

restores (A) intracellular Ca2+ overload (magnification,

×20), (B) mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation

(magnification, ×20) and (C) alterations in the expression of

apoptosis-related proteins. Cells were pretreated with 25 μM LQ for

3 h and exposed to 20 mM Glu for (A and B) 12 h or (C) 24 h. Bcl-2,

Bax and cytosolic cyto c expression was normalized using

GAPDH. Data are expressed as a percentage of the value in the

corresponding control group and are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation of three replicate experiments.

#P<0.05 vs. control group; *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01 vs. Glu-treated cells. LQ, liquiritin; Glu,

glutamate; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; Bax, Bcl2-associated X

protein; cyto c; cytochrome c; CTRL, control. |

Mitochondrial function is one of the factors

responsible for cell apoptosis. JC-1 staining revealed that

pretreatment with 25 μM LQ (21)

significantly restored the glutamate-induced dissipation of Δψm, as

indicated by an increase in red fluorescence in the LQ-pretreated

cells compared with those treated solely with glutamate (Fig. 3B).

Glutamate exposure was found to enhance Bax

expression by 11%, reduce Bcl-2 expression by 20% and increase

cytosolic cyto c expression by 10% compared with the

non-treated control cells (all P<0.05). However, LQ markedly

reduced the glutamate-induced increase in Bax and cytosolic cyto

c expression to normal levels, and enhanced the expression

of Bcl-2 (P<0.05) (Fig.

3C).

ERK and AKT/GSK3β activation contributes

to LQ-mediated neuroprotection in DPC12 cells

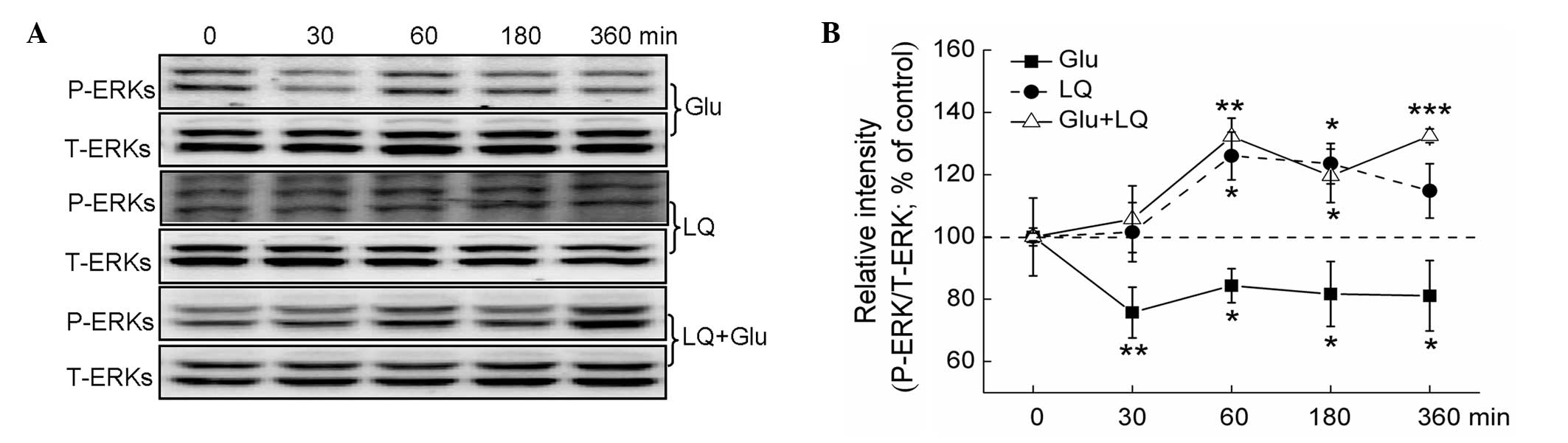

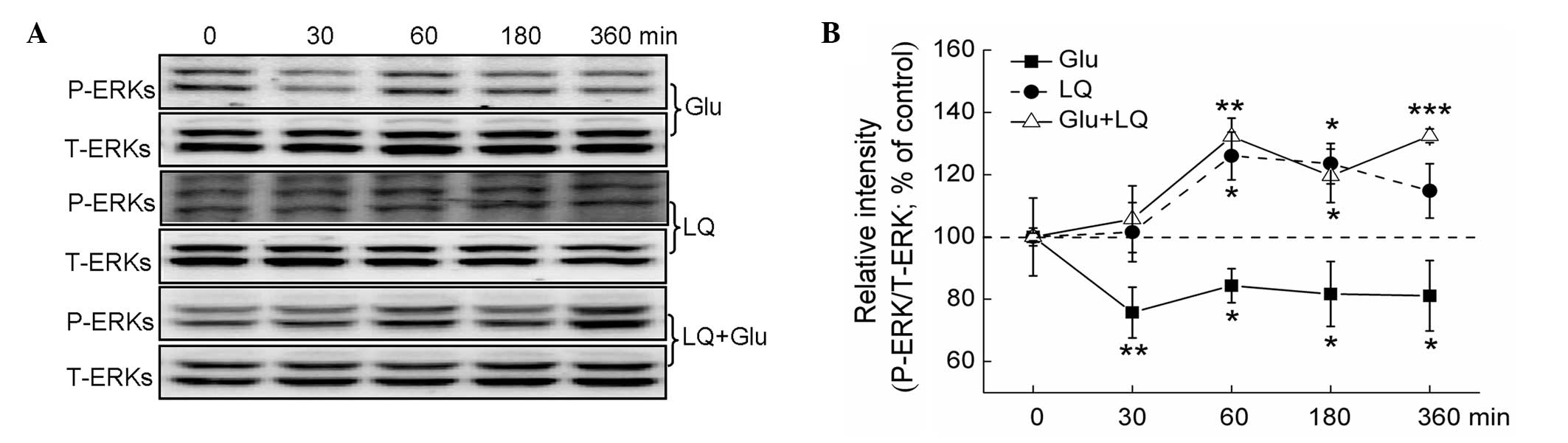

ERK and AKT/GSK3β activation was detected in DPC12

cells. While glutamate exposure for between 30 and 360 min was

found to significantly inhibit ERK phosphorylation, exposure to 25

μM LQ alone for 60 and 180 min was found to significantly enhance

the expression of P-ERKs (P<0.05). Furthermore, pretreatment

with LQ for between 60 and 360 min was observed to significantly

reverse the glutamate-induced suppression of P-ERK expression

(P<0.05) (Fig. 4A and B).

| Figure 4ERK pathways are involved in

LQ-mediated neuroprotection against Glu-induced cell damage. DPC12

cells were treated with LQ or Glu alone and collected at 0, 30, 60,

180 and 360 min. For LQ and Glu co-treatment, DPC12 cells were

pretreated with 25 μM LQ for 3 h, followed by Glu. Cells were then

collected at 0, 30, 60, 180 and 360 min subsequent to Glu exposure

(A) Expression of P-ERKs and T-ERKs detected using western blot

analysis. (B) Quantification of the expression of P-ERKs and

T-ERKs. The expression of P-ERKs was normalized using that of

T-ERKs. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of

three replicate experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. cells

collected at 0 min. ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase;

Glu, glutamate; LQ, liquiritin; P-, phosphorylated; T-, total. |

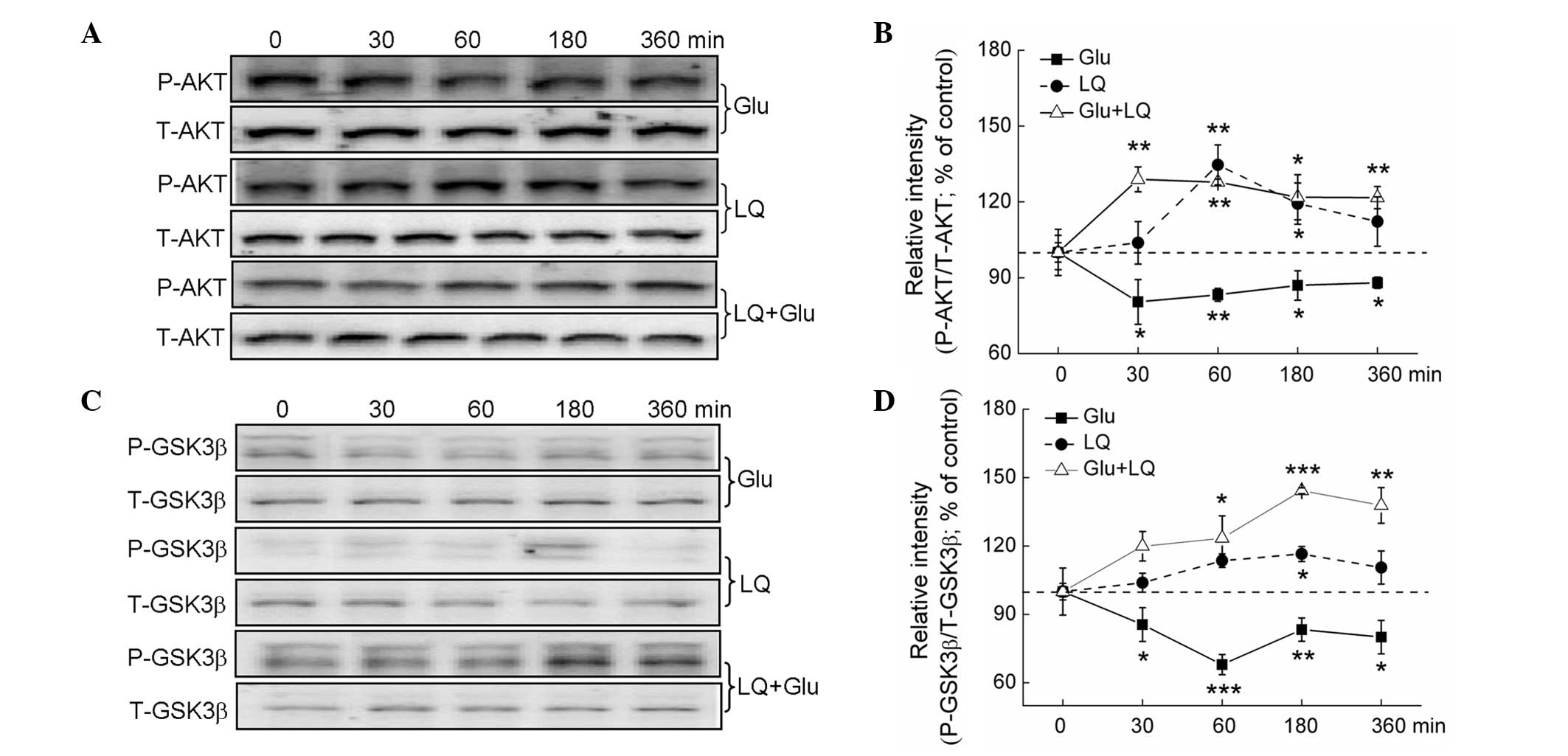

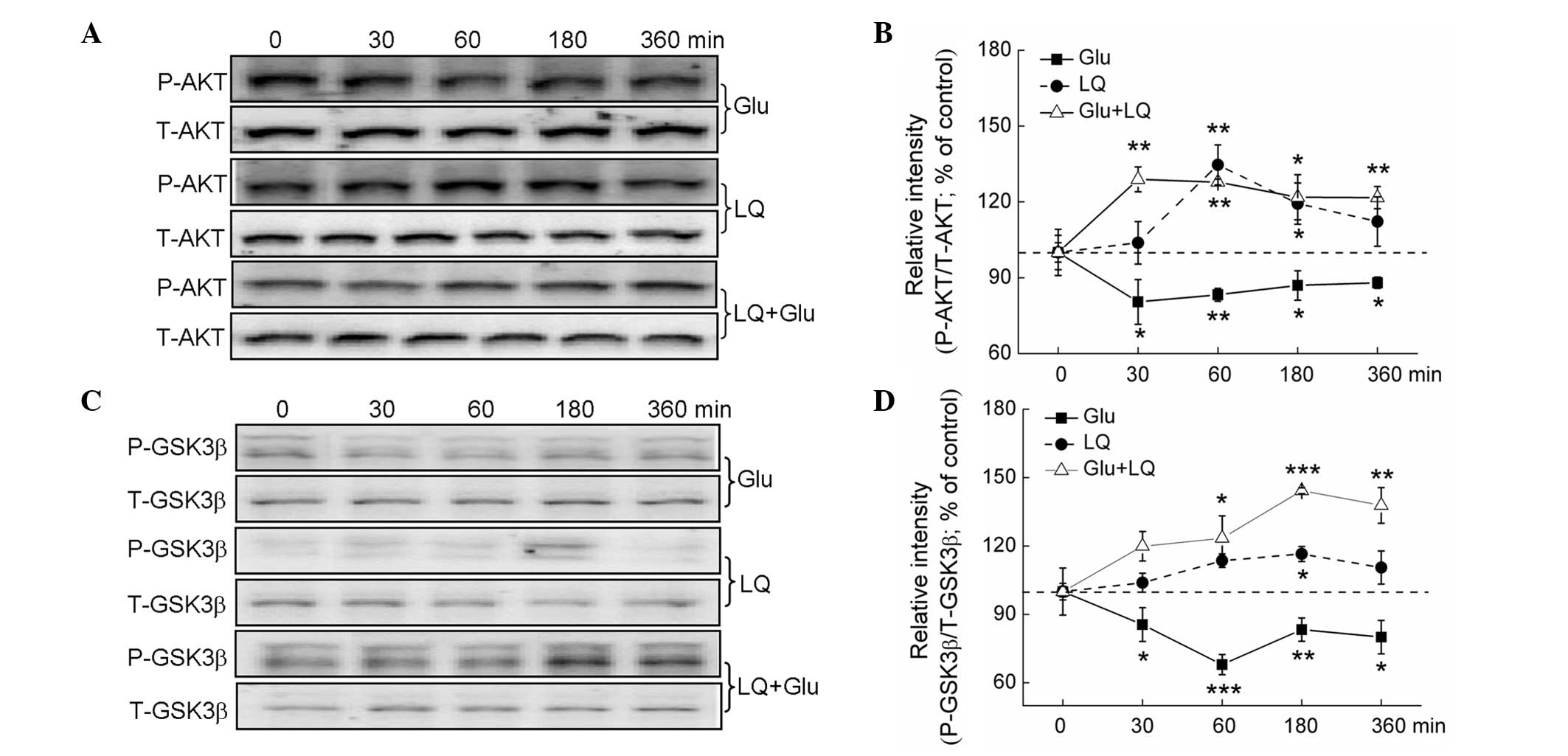

PI3K/AKT are crucial regulators of

glutamate-mediated cell damage (17). Glutamate treatment for between 30

and 360 min was found to significantly suppress P-AKT and P-GSK3β

expression. Exposure to LQ alone and in combination with glutamate

resulted in a time-dependent increase in P-AKT and P-GSK3β

expression (P<0.05), but did not affect expression of T-AKT and

T-GSK3β (Fig. 5A–D).

| Figure 5The AKT/GSK3β pathway contributes to

LQ-mediated neuroprotection against Glu-induced cell damage. DPC12

cells were treated with LQ or Glu alone and collected at 0, 30, 60,

180 and 360 min. For LQ and Glu co-treatment, DPC12 cells were

pretreated with 25 μM LQ for 3 h, followed by Glu. Cells were then

collected at 0, 30, 60, 180 and 360 min subsequent to Glu exposure.

(A and C) Expression of P-AKT, T-AKT, P-GSK3β and T-GSK3β detected

using western blot analysis. (B and D) Quantification of P-AKT and

P-GSK3β expression, normalized using T-AKT and T-GSK-3β expression,

respectively. Data are expressed as a percentage of the value in

the corresponding control group and presented as the mean ±

standard deviation of three replicate experiments.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. cells collected at 0 min. GSK3β,

glycogen synthase kinase-3β; P-, phosphorylated; T-, total; LQ,

liquiritin; Glu, glutamate. |

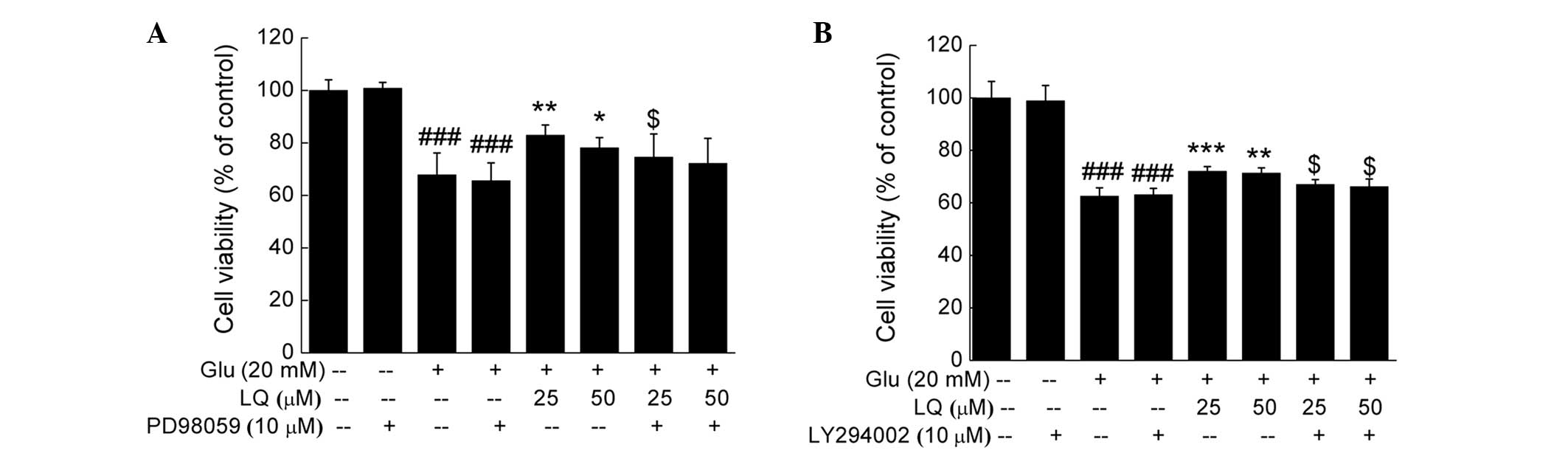

DPC12 cells underwent 30 min pretreatment with 10 μM

ERK or PI3K inhibitor, PD98059 or LY294002 respectively, followed

by 3 h treatment with LQ and 24 h exposure to glutamate. Treatment

with PD98059 or LY294002 did not affect cell viability compared

with the untreated or glutamate-treated cells; however, it was

found to significantly reduce the potency of LQ in enhancing cell

viability (P<0.05) (Fig.

6).

Discussion

The present study investigated the neuroprotective

effect of LQ against glutamate-induced cell damage and its

underlying mechanism. LQ was found to significantly attenuate the

glutamate-induced decrease in DPC12 cell viability and apoptotic

alterations, including mitochondrial function, the expression of

apoptosis-related proteins, intracellular Ca2+

concentration and LDH release. Furthermore, the activation of ERKs

and AKT/GSK-3β was found to contribute to LQ-mediated

neuroprotection.

Dissipation of Δψm and elevated mitochondrial cyto

c release were observed in glutamate-exposed DPC12 cells.

Experimental evidence has indicated that mitochondria have a key

role in executing important intracellular events associated with

neuronal survival and apoptosis (21). Certain apoptosis-related proteins,

including Bcl-2 and Bax, target the mitochondria and induce

mitochondrial swelling or increase the permeability of the

mitochondrial membrane. This leads to the efflux of apoptotic

effectors from the mitochondria (22,23).

Cyto c, released from mitochondria, serves as a regulatory

factor in morphological apoptosis-related changes (24). In the present study, after 3 h

pretreatment with LQ, the glutamate-induced dissipation of Δψm was

markedly restored and the expression of Bcl-2, Bax and cytosolic

cyto c was normalized. These findings indicate that the

neuroprotective effect of LQ may, at least partly, be attributed to

its restoration of Δψm through upregulation of the activity of

mitochondria-dependent apoptotic molecules.

AKT activation is associated with cell survival and

proliferation (25). GSK-3β, a

constitutively active enzyme substrate of AKT, is inactivated by

P-AKT (26). It has been reported

that GSK-3β inactivation is involved in the guanosine-mediated

protective effects against glutamate-induced cell death in SH-SY5Y

cells (26). Furthermore, GSK-3β

inhibition has been found to protect against ischemia/reperfusion

organ injury (27). In the present

study, exposure to LQ alone or in combination with glutamate was

observed to markedly enhance P-AKT and P-GSK3β levels in a

time-dependent manner in DPC12 cells compared with untreated cells.

In addition, pretreatment with the PI3K/AKT inhibitor LY294002 was

found to partially antagonize the LQ-induced increase in cell

viability. Furthermore, the increase in AKT activation observed

upon pretreatment with LQ resulted in an increase in GSK3β

phosphorylation, which has an important role in LQ-mediated

neuroprotection. Previous studies have suggested that the

activation of AKT regulates the expression of Bcl-2 (28). The AKT/Bcl-2 pathway contributes to

the protective effect of sodium ferulate in cultured cortical

neurons (17). Bcl-2 acts as an

upstream checkpoint of mitochondrial function (29); therefore, the findings of the

present study may indicate that mitochondrial function is

associated with AKT activation in LQ-exposed DPC12 cells.

ERKs were also analyzed in the present study.

Treatment with LQ alone or in combination with glutamate was found

to induce rapid phosphorylation of ERKs, whereas glutamate

treatment alone was observed to reduce P-ERK expression. PD98059

diminished the protective effect of LQ against the

glutamate-induced neurotoxicity and reduction in cell viability. It

has previously been reported that the inhibition of ERKs using a

specific inhibitor results in downregulation of Bcl-2 (30). These findings suggest that the

protective effect mediated by LQ may be achieved through ERK

pathways, which may be associated with mitochondrial function.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, the

present study provides the first experimental evidence that LQ has

a neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced cell damage, and

that this effect is associated with ERK and AKT/GSK3β pathways in

DPC12 cells. These findings suggest that LQ may have potential as a

therapeutic agent for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases

and neural injury.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the

National Science and Technology support program of P.R. China

(grant no. 2012BAL29B05).

References

|

1

|

Wang CY, Kao TC, Lo WH and Yen GC:

Glycyrrhizic acid and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid modulate

lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response by suppression of

NF-κB through PI3K p110δ and p110γ inhibitions. J Agric Food Chem.

59:7726–7733. 2011.

|

|

2

|

Birari RB, Gupta S, Mohan CG and Bhutani

KK: Antiobesity and lipid lowering effects of Glycyrrhiza

chalcones: experimental and computational studies. Phytomedicine.

18:795–801. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kwon HJ, Kim HH, Ryu YB, et al: In vitro

anti-rotavirus activity of polyphenol compounds isolated from the

roots of Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Bioorg Med Chem.

18:7668–7674. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wu TY, Khor TO, Saw CL, et al:

Anti-inflammatory/anti-oxidative stress activities and differential

regulation of Nrf2-mediated genes by non-polar fractions of tea

Chrysanthemum zawadskii and licorice Glycyrrhiza

uralensis. AAPS J. 13:1–13. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kao TC, Shyu MH and Yen GC:

Neuroprotective effects of glycyrrhizic acid and

18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid in PC12 cells via modulation of the

PI3K/Akt pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 57:754–761. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang W, Hu X, Zhao Z, et al:

Antidepressant-like effects of liquiritin and isoliquiritin from

Glycyrrhiza uralensis in the forced swimming test and tail

suspension test in mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.

32:1179–1184. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chen ZA, Wang JL, Liu RT, et al:

Liquiritin potentiate neurite outgrowth induced by nerve growth

factor in PC12 cells. Cytotechnology. 60:125–132. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sun YX, Tang Y, Wu AL, et al:

Neuroprotective effect of liquiritin against focal cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion in mice via its antioxidant and antiapoptosis

properties. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 12:1051–1060. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, et

al: Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and

function. Pharmacol Rev. 62:405–496. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nicholls DG: Mitochondrial dysfunction and

glutamate excitotoxicity studied in primary neuronal cultures. Curr

Mol Med. 4:149–177. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jang JY, Kim HN, Kim YR, et al: Hexane

extract from Polygonum multiflorum attenuates

glutamate-induced apoptosis in primary cultured cortical neurons. J

Ethnopharmacol. 145:261–268. 2013.

|

|

12

|

Zhang M, Li J, Geng R, et al: The

inhibition of ERK activation mediates the protection of

necrostatin-1 on glutamate toxicity in HT-22 cells. Neurotox Res.

24:64–70. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ

and Greenberg ME: Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases

on apoptosis. Science. 270:1326–1331. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lin YL, Wang GJ, Huang CL, et al:

Ligusticum chuanxiong as a potential neuroprotectant for

preventing serum deprivation-induced apoptosis in rat

pheochromocytoma cells: functional roles of mitogen-activated

protein kinases. J Ethnopharmacol. 122:417–423. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lou H, Fan P, Perez RG and Lou H:

Neuroprotective effects of linarin through activation of the

PI3K/Akt pathway in amyloid-β-induced neuronal cell death. Bioorg

Med Chem. 19:4021–4027. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lu S, Lu C, Han Q, et al: Adipose-derived

mesenchymal stem cells protect PC12 cells from glutamate

excitotoxicity-induced apoptosis by upregulation of XIAP through

PI3-K/Akt activation. Toxicology. 279:189–195. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jin Y, Yan EZ, Fan Y, et al:

Neuroprotection by sodium ferulate against glutamate-induced

apoptosis is mediated by ERK and PI3 kinase pathways. Acta

Pharmacol Sin. 28:1881–1890. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mosmann T: Rapid colorimetric assay for

cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and

cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 65:55–63. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cossarizza A, Baccarani-Contri M,

Kalashnikova G and Franceschi C: A new method for the

cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using

the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine

iodide (JC-1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 197:40–45.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang CL, Chik SC, Li JC, Cheung BK and Lau

AS: Identification of the bioactive constituent and its mechanisms

of action in mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of black

cohosh and related Cimicifuga species on human primary blood

macrophages. J Med Chem. 52:6707–6715. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lee CS, Kim YJ, Lee MS, Han ES and Lee SJ:

18beta-Glycyrrhetinic acid induces apoptotic cell death in SiHa

cells and exhibits a synergistic effect against antibiotic

anti-cancer drug toxicity. Life Sci. 83:481–489. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A and Levi-Schaffer F:

Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction.

Apoptosis. 5:415–418. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ricci JE, Gottlieb RA and Green DR:

Caspase-mediated loss of mitochondrial function and generation of

reactive oxygen species during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 160:65–75.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dejean LM, Martinez-Caballero S and

Kinnally KW: Is MAC the knife that cuts cytochrome c from

mitochondria during apoptosis? Cell Death Differ. 13:1387–1395.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, et al:

Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein

kinase Akt. Science. 275:661–665. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Dal-Cim T, Molz S, Egea J, et al:

Guanosine protects human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells against

mitochondrial oxidative stress by inducing heme oxigenase-1 via

PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway. Neurochem Int. 61:397–404. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ha T, Hua F, Liu X, et al:

Lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial protection against

ischaemia/reperfusion injury is mediated through a

PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism. Cardiovasc Res. 78:546–553. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ahmed NN, Grimes HL, Bellacosa A, Chan TO

and Tsichlis PN: Transduction of interleukin-2 antiapoptotic and

proliferative signals via Akt protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 94:3627–3632. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chao DT and Korsmeyer SJ: BCL-2 family:

regulators of cell death. Annu Rev Immunol. 16:395–419. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Boucher MJ, Morisset J, Vachon PH, Reed

JC, Lainé J and Rivard N: MEK/ERK signaling pathway regulates the

expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), and Mcl-1 and promotes survival of

human pancreatic cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 79:355–369. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|