Introduction

Microglial cells, resident brain macrophages of the

central nervous system (CNS), are pivotal in the pathogenesis of

several neurodegenerative diseases (1). Microglia are activated in response to

stress, and are involved in innate and adaptive immune responses by

inducing the production of various pro-inflammatory mediators,

including nitric oxide (NO), inducible NO synthase (iNOS), tumor

necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, nuclear

factor-κB (NFκB), caspase-3 and heat shock protein (HSP) 60

(2–6), all of which contribute to

neurodegeneration (7,8). A number of microglia-targeted

pharmacotherapies, such as protein kinase C inhibitors and

microglia-inhibiting factors, have been proposed to suppress

microglial activation and promote neuronal survival in vivo

(9–11). However, the inability of these

drugs to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and the complexity of

current pharmacological agents, as well as the possible side

effects, has halted long-term clinical use in the treatment and

prevention of diseases of the CNS (12).

Dextromethorphan (DM), a derivative of morphinan, is

one of the most widely used non-opioid cough suppressants, acting

as the active ingredient in numerous antitussive formulations

(13). As an antitussive, DM is

superior to opioids used at antitussive doses in that DM lacks any

gastrointestinal side effects, such as constipation, and produces a

lower degree of depression of the CNS. DM is rapidly absorbed from

the gastrointestinal tract, where it enters the bloodstream and

crosses the blood-brain barrier (14). The anticonvulsant and

neuroprotective properties of DM have been demonstrated, and

treatment with DM has been shown to improve the cerebrovascular and

functional consequences of global cerebral ischemia (14). However, the mechanisms underlying

the neuroprotective effects of DM remain poorly understood.

Previous studies have demonstrated that naloxone,

another analogue of morphinan, protects against lipopolysaccharide

(LPS)-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo

through the inhibition of the release of proinflammatory factors

and free radicals (15–18). DM is structurally similar to

naloxone and has been shown to protect against LPS-induced dopamine

neurodegeneration in mixed neuron-glia coculture through the

inhibition of microglial overactivation, and the subsequent

reduction in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, free radicals

and reactive oxygen species (19).

In the present study, the DeltaVision Elite microscopy imaging

system was used to analyze the effects of DM on the production of

proinflammatory mediators.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following reagents were used in this study: DM

and LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); rabbit monoclonal

antibodies against β-actin and NF-κB p65 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA,

USA); mouse monoclonal anti-HSP60 and anti-heat shock factor 1

(HSF1) antibodies (Stressgen®, San Diego, CA, USA; Enzo

Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA); rabbit polyclonal

anti-caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly,

MA, USA); proteinase inhibitor cocktails (Merck Chemicals,

Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA); IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α ELISA kits

(eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA); bicinchoninic acid (BCA) and

enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kits (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.,

Rockford, IL, USA); Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and

fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA); Griess

reagent and iNOS kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute,

Nanjing, China); Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Beyotime Biotech,

Jiangsu, China); and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated

Affinipure goat anti-rabbit and tetramethylrhodamine

(TRITC)-conjugated Affinipure goat anti-mouse antibodies (Abcam).

All additional materials were purchased from ZSGB-BIO (Beijing,

China), unless otherwise stated.

Microglial cell culture

BV2 mouse microglial cells (Shanghai Cell Bank,

Shanghai, China) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS,

penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 g/ml). The cultures

were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 95%

O2 and 5% CO2. The cells were treated with 1

μg/ml LPS for 30 min, followed by administration of 10, 25, 50, 80

or 100 μM DM (dissolved in PBS) for 24 h.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using a CCK-8 assay. BV2

cells (5×104 cells in 100 μl/well) were seeded in

96-well plates. CCK-8 solution (10 μl) was added to each well and

the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 90 min. The absorbance at

450 nm was measured using a SmartSpec Plus Spectrophotometer

(Bio-Rad, Beijing, China). The results are plotted as the means ±

standard deviation (SD) of three separate experiments with four

determinations per experiment for each experimental condition. The

cell survival ratio was calculated, normalizing the results to the

control group (without LPS+DM).

ELISA

The levels of IL-6, IL-1β, HSP60 and TNF-α present

in the culture medium, were quantified according to the

manufacturer’s instructions for the respective ELISA kits. The

absorbance was determined at 450 nm using a Model 680 microplate

reader (Bio-Rad, Beijing, China).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed according to a

standard method. Briefly, BV2 cells were washed with PBS three

times and lyzed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. The

protein concentration was determined using the BCA kit according to

the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal quantities of each protein

sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked with

5% milk powder and incubated with the respective primary antibodies

(anti-P65 1;1,000; anti-caspase, 1:1,000; anti-HSP60, 1:1,000;

anti-HSF-1, 1:200; and anti-β-actin, 1:5,000) in Tris-buffered

saline with Tween-20 (TBST) overnight at 4°C. Subsequent to rinsing

in milk-TBST, the blots were incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000). The target

proteins were detected by using the ECL detection system and X-ray

films.

Immunofluorescence

BV2 cells (5×104 cells in 100 μl/well)

were seeded on coverslips in 24-well plates. Following 24 h

incubation, the cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 1 h and

then incubated with the indicated concentrations of DM for 24 h.

Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, washed three times with PBS and

then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min. The

cells were again washed three times with PBS and blocked with 5%

bovine serum albumin for 1 h at 37°C. Following blocking, the cells

were incubated with primary antibodies (anti-P65 1;100;

anti-caspase, 1:100; anti-HSP60, 1:200; anti-HSF-1, 1:50; and

anti-iNOS, 1:100) in PBS overnight at 4°C, then rinsed with PBS,

and incubated with the FITC- and TRITC-conjugated secondary

antibodies (1:1,000) for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were then washed

with PBS, stained with DAPI and then mounted. Images were captured

at magnification, ×400 using a DeltaVision Elite microscopy imaging

system (Applied Precision; GE Healthcare, Issaquah, WA, USA).

Statistics

Statistical differences were determined using a

one-way analysis of variance test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significance difference. The data

represent the means ± standard error of the mean.

Results

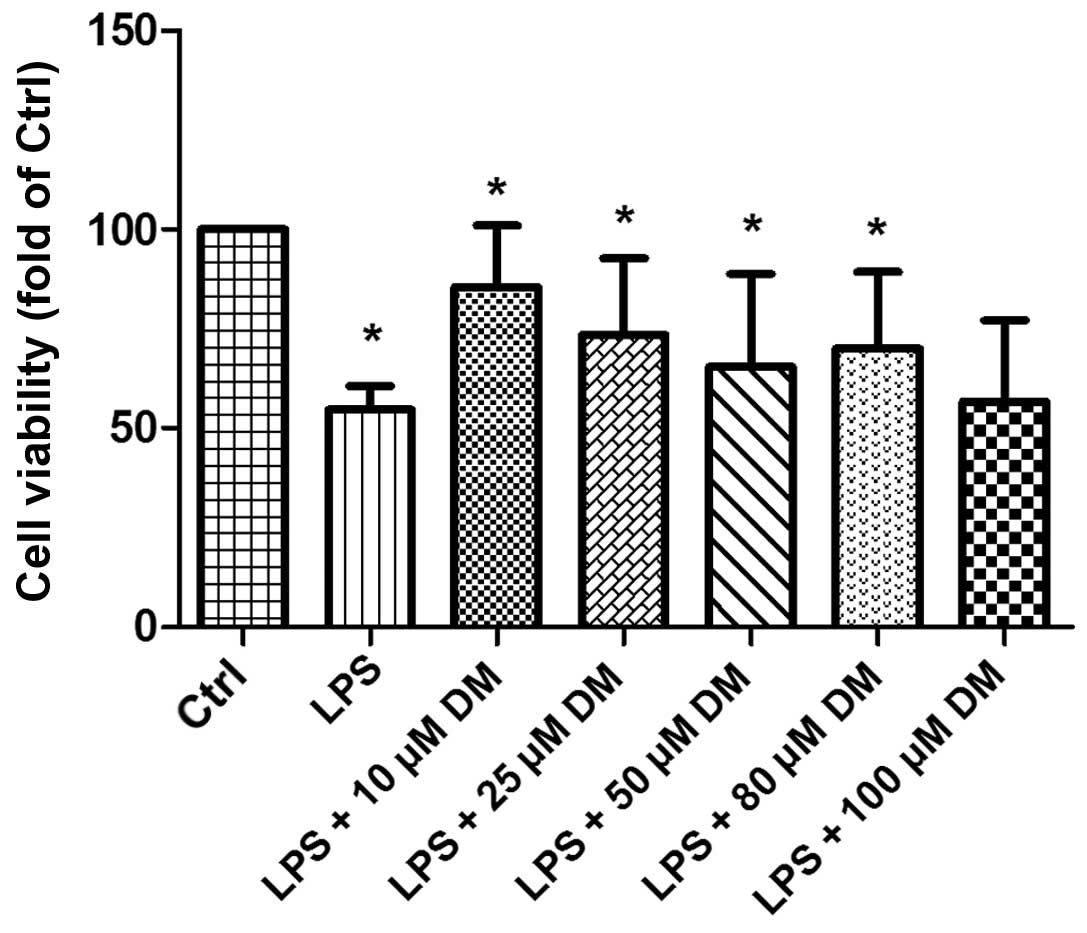

DM promotes the viability of BV2

microglia

To determine whether DM exerts an effect on the

viability of LPS-stimulated BV2 cells, a CCK-8 assay was performed.

The results demonstrated that the microglia group treated with

10–100 μM DM for 24 h exhibited significantly increased cell

viability following LPS stimulation, as compared with the group

treated with LPS alone (Fig. 1).

The cells treated with 10 μM DM exhibited the maximal viability, as

compared with the other concentrations, thus 10 μM was selected for

subsequent experiments. The results indicated that DM may exert a

positive effect on the viability of LPS-stimulated BV2

microglia.

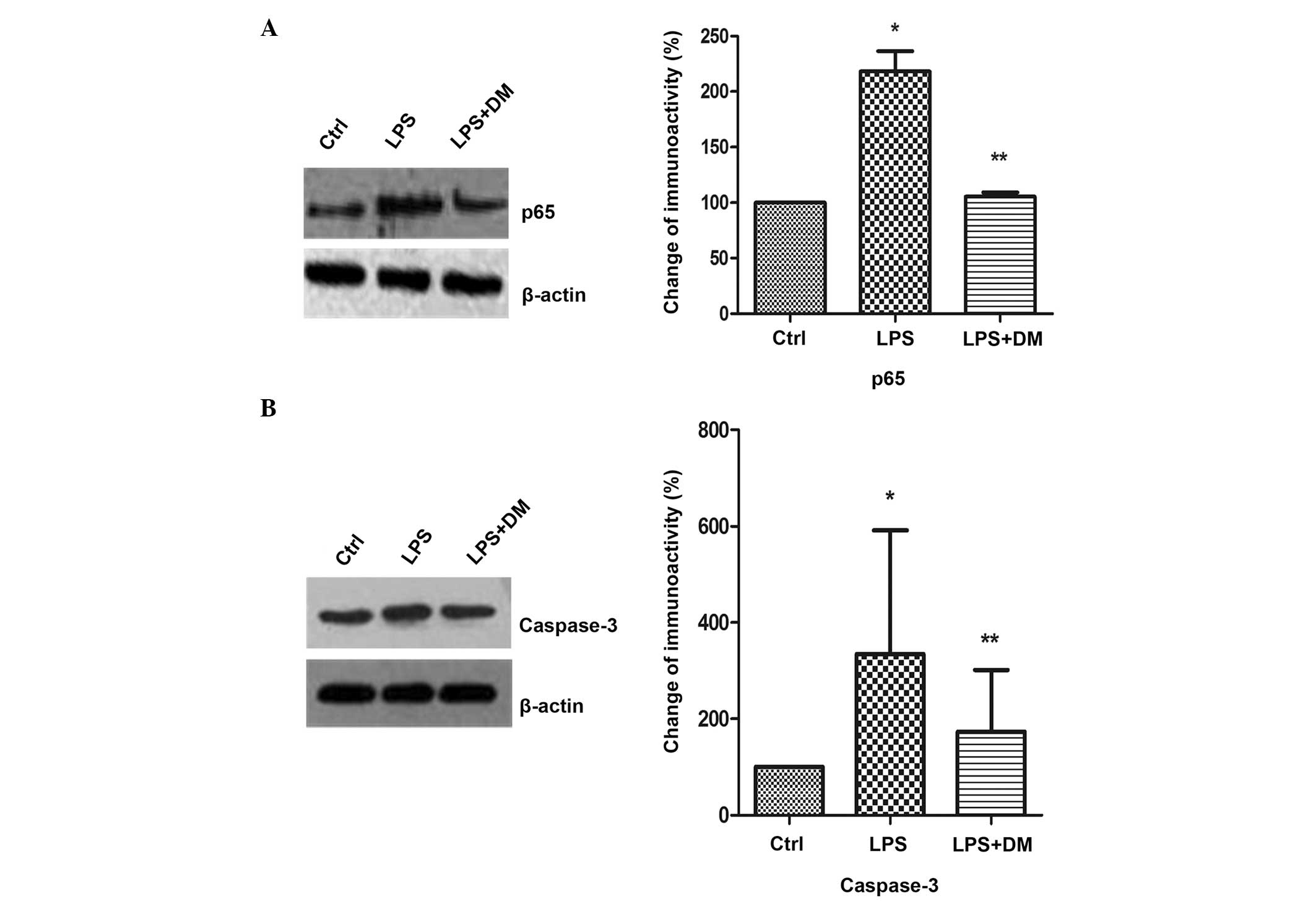

DM inhibits NFκB and caspase-3

expression

NFκB regulates the expression of numerous

proinflammatory factors and caspase-3 is an important protein in

the NFκB signaling pathway. Inhibition of caspase-3 prevents the

neuronal loss induced by activated microglia in brain diseases.

Therefore, the effects of DM on NFκB and caspase-3 expression

levels in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia were investigated using

western blotting. The levels of the p65 subunit of NFκB were

significantly increased following LPS treatment, as compared with

the control (P<0.05), but were markedly inhibited by DM, as

compared with LPS treatment alone (P<0.05; Fig. 2A). Subsequent to LPS stimulation,

caspase-3 expression was found to be significantly suppressed

following DM treatment, as compared with LPS treatment only

(P<0.05; Fig. 2B).

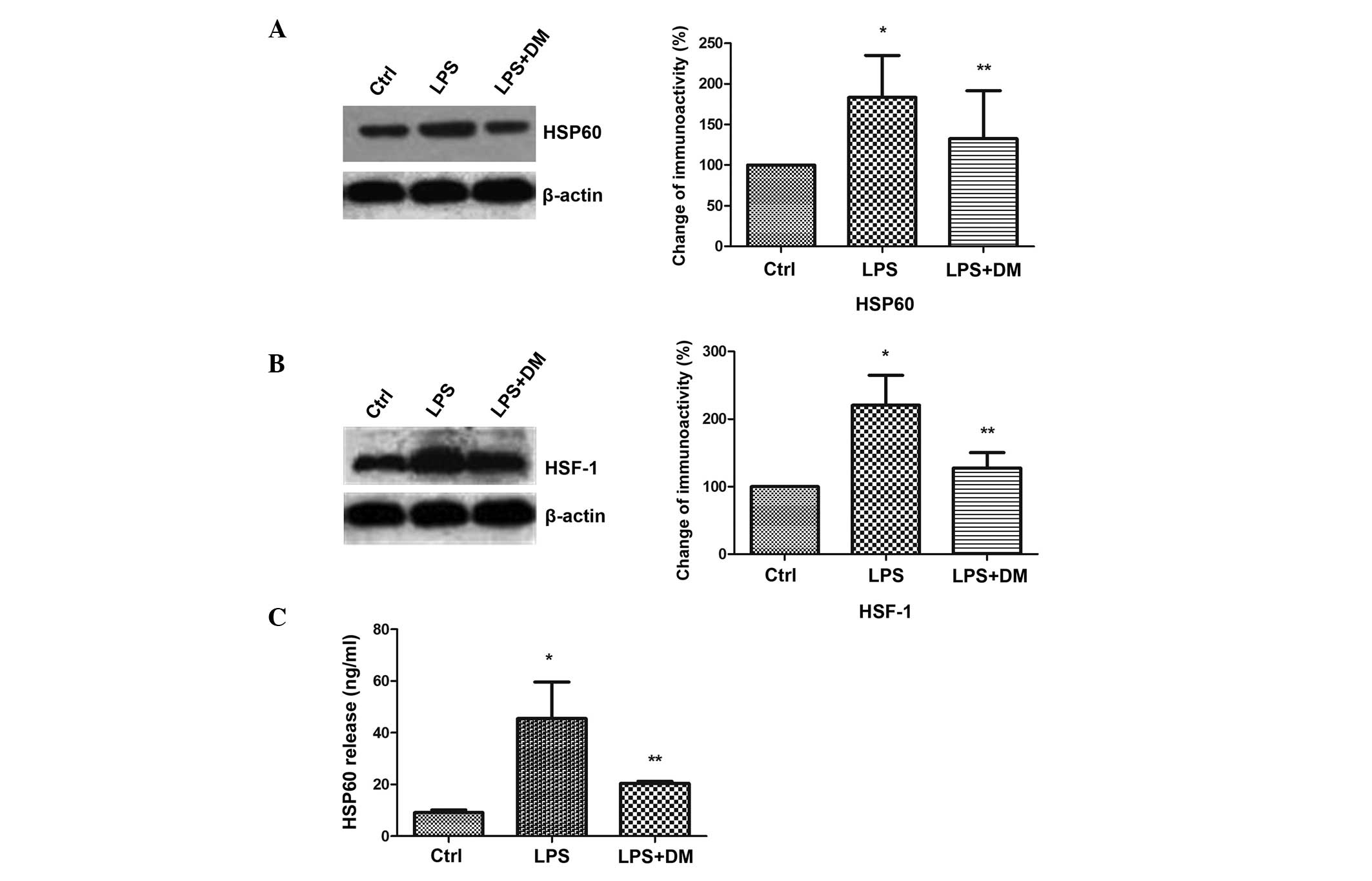

DM inhibits HSP60 protein expression and

release in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia

The levels of HSP60 expression and release were

detected in activated BV2 cells. The western blotting results

demonstrated that LPS significantly enhanced HSP60 expression

levels, as compared with those of the control group (P<0.05),

but DM significantly inhibited this increase, as compared with LPS

treatment alone (P<0.05; Fig.

3A). HSF-1 has been shown to bind with the heat shock element

on the HSP60 promoter to regulate HSP60 gene expression (20). Therefore, the HSF-1 expression

levels were analyzed and were found to be significantly upregulated

by LPS (P<0.05), but significantly downregulated by additional

DM treatment (P<0.05). This indicated that HSP60 expression was

induced by HSF-1 (Fig. 3B). HSP60

has been reported to translocate extracellularly upon stress to

exert injury effects (21). The

ELISA results demonstrated that HSP60 was released into the culture

medium upon LPS-mediated activation of BV2, but the increased

expression levels of extracellular HSP60 was significantly

suppressed by the addition of DM (P<0.05; Fig. 3C).

DM inhibits proinflammatory factor

production

ELISA assay was used to determine whether DM

suppresses the release of proinflammatory factors, including NO,

iNOS, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells. As shown

in Fig. 4, 24 h LPS treatment of

BV2 cells resulted in significant increases in the levels of the

investigated proinflammatory factors in the culture media, as

compared with the control (all P<0.05). However, additional DM

treatment significantly reduced the release of all proinflammatory

factors, as compared with LPS treatment alone (P<0.05). These

results indicated that DM effectively suppressed the production of

neurotoxic factors in overactivated microglia.

Immunofluorescence

To confirm the results from traditional molecular

techniques (western blotting and ELISA), immunofluorescence

experiments were conducted. The staining patterns of protein

localization using anti-HSP60, HSF-1, NFκB, caspase-3 and iNOS

antibodies in LPS- and LPS+DM-treated cells were markedly

different. The fluorescence intensities with those antibodies were

markedly higher in the LPS group as compared with those in the DM

group (Fig. 5A). The statistical

analysis is shown in Fig. 5B and

is consistent with the findings from the western blotting and

ELISA. From these data, DM may be considered to effectively inhibit

HSP60, HSF-1, NF-κB, caspase-3 and iNOS expression in

LPS-stimulated microglia.

| Figure 5Dextromethorphan (DM) inhibits heat

shock protein 60 (HSP60), heat shock factor 1 (HSF-1), nuclear

factor-κB (NFκB), caspase-3 and inducible nitric oxide synthase

(iNOS) expression in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells, as

detected by immunofluorescence. The cells were pretreated with

lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 0.5 h, followed by incubation with 10

μM DM for 24 h. (A) The expression fluorescence intensity of HSP60,

HSF-1, iNOS, NFκB and caspase-3 varied between the control, LPS and

LPS + DM groups. The arrows indicate the various subcellular

localization of the respective proteins in the cells. All the

images were produced by merging the cytoplasmic and nuclear images

(digital image capture, magnification, ×400). (B) Statistical

analysis of the signal intensities of HSP60, HSF-1, NFκB, caspase-3

and iNOS. The data represent the means ± standard error of the mean

of each separate experiment performed. *P<0.05, as

compared with the Ctrl group. **P<0.05, as compared

with the LPS group. Ctrl, control. |

Discussion

In the present study, treatment with 10 μM DM was

demonstrated to effectively inhibit LPS-induced activation of

microglia. DM reduced the expression levels of NFκB, caspase-3,

HSP60, HSF-1 and iNOS in microglia, and effectively suppressed the

release into the culture medium of HSP60, NO and several

proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, in

microglia stimulated by LPS. Therefore, the data suggest that DM

may be a useful therapeutic agent in the treatment of inflammatory

diseases.

The activation of microglia is important in neural

parenchymal defence against infectious diseases, as well as

inflammation, trauma, ischaemia, brain tumors and neurodegeneration

(22). The activated microglia

secrete various proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors that are

hypothesized to induce neurodegeneration (23). Therefore, the identification of

novel strategies to reduce microglial overactivation is of

therapeutic importance, and the inhibition of proinflammatory

enzymes and cytokines may be an effective therapeutic approach

against these neurodegenerative disorders. Previous studies have

investigated the neuroprotective effects of several substances,

including polysaccharides from Lycium barbarum (11), curcumin (24), fucoidan (25) and naloxone (unpublished data). The

present study suggests that DM is also a potential therapeutic

tool.

Numerous studies have reported that DM exerts

neuroprotective effects (26–28).

DM is considered to be an antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate

(NMDA) receptor complex. Therefore the mechanism responsible for

the neuroprotective activity of DM has been hypothesized to occur

through antagonistic effects on the NMDA receptor (29). However, explaining the numerous

observed beneficial effects becomes difficult due to the

identification of high (nanomolar) and low (micromolar) affinity

binding sites for DM in the CNS (30,31).

In the present study, the neuroprotective effects of DM in the

inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative disorders were found to

have been most likely mediated by the inhibition of LPS-induced

microglial activation and the suppression of neurotoxic factor

production, but not by glutamate-mediated excitatory

neurotoxicity.

The activation of NFκB is considered to be pivotal

in the inflammatory response resulting from microglial activation.

NFκB is a multifunctional transcription factor and is an important

target in controlling inflammation, as the transcription of

numerous proinflammatory molecules depends on the activation of

NFκB (32,33). Therefore, several anti-inflammatory

therapies have aimed to inhibit NFκB activity in LPS models or

inflammatory diseases (34).

Caspase-3 is crucial in cell death and CNS inflammation (35). LPS-stimulated microglia have been

demonstrated to be non-toxic to neighboring neurons when

caspase-3/7 is inhibited (36).

The activation of NFκB by caspase-3 is also critical in

inflammation. Thus, in the present study, the effects of DM on NFκB

and caspase-3 expression levels were detected. The results

demonstrated that DM treatment following LPS stimulation markedly

inhibited caspase-3 and the NFκB downstream mediator p65,

suggesting that the anti-inflammatory effects of DM may be a result

of inhibition of the NFκB signaling pathway.

HSP60 is primarily considered to be a mitochondrial

protein, but may translocate to the plasma membrane, even being

released extracellularly upon stress, which is a process that has

been demonstrated to be induced by the NFκB-p65 cascade (21). Extracellular HSP60 may become toxic

by targeting self-reactive T cells in inflammatory diseases

(37). HSP60 gene expression is

regulated by the corresponding transcription factor, HSF-1, which

binds to the HSP60 gene promoter. NFκB has also been shown to

initiate transcription of the HSP60 stress gene, which elicits a

potent proinflammatory response in innate immune cells (38). TNF-α is a mediator of NFκB

signaling and induces an increase in the expression levels of

HSP60, which has been shown to be reversed by p65 inhibition

(38). Therefore, in the present

study, HSP60 expression in BV2 cells and extracellular release, as

well as TNF-α levels in the culture medium were measured, following

NFκB activation by LPS. The results reveal that DM suppressed HSP60

expression and release, and also reduced extracellular TNF-α

levels.

Microglial activation is widely known to produce

proinflammatory cytokines, NO and iNOS. This was confirmed in the

present study by measuring the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, NO and iNOS

in the culture medium of BV2 cells stimulated by LPS. The iNOS gene

is under the transcriptional control of various inflammatory

mediators, including cytokines and LPS. NO, a product of iNOS, has

been found to be important as a signaling molecule in a number of

areas of the body, as well as acting as a cytotoxic or regulatory

effector molecule of the innate immune response (39). However, in the present study,

following DM treatment, IL-1β, IL-6, NO and iNOS expression levels

were markedly inhibited.

Combined with results from previous studies, the

findings from the present study indicate that DM may exert

neuroprotective action through the inhibition of the NFκB signaling

pathway to prevent the overactivation of microglia.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31060140 and 31260243), the

Project-sponsored by SRF for ROCS and State Education Ministry.

Additional funding was provided to Dr Yin Wang by the Program for

New Century Excellent Talents in University.

References

|

1

|

Block ML, Zecca L and Hong JS:

Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular

mechanisms. Nature Rev Neurosci. 8:57–69. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hanisch UK and Kettenmann H: Microglia:

active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and

pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 10:1387–1394. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y and Kreutzberg GW:

Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res

Rev. 20:269–287. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Innamorato NG, Lastres-Becker I and

Cuadrado A: Role of microglial redox balance in modulation of

neuroinflammation. Curr Opin Neurol. 22:308–314. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lynch MA: The multifaceted profile of

activated microglia. Mol Neurobiol. 40:139–156. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li YH, Teng P, Wang Y, et al: Expression

and regulation of HSP60 in activated microglia cells. J Ningxia Med

Coll. 8:712–714. 2011.

|

|

7

|

Zhang D, Sun L, Zhu H, et al: Microglial

LOX-1 reacts with extracellular HSP60 to bridge neuroinflammation

and neurotoxicity. Neurochem Int. 61:1021–1035. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lehnardt S, Schott E, Trimbuch T, et al: A

vicious cycle involving release of heat shock protein 60 from

injured cells and activation of toll-like receptor 4 mediates

neurodegeneration in the CNS. J Neurosci. 28:2320–2331. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Thanos S, Mey J and Wild M: Treatment of

the adult retina with microglia-suppressing factors retards

axotomy-induced neuronal degradation and enhances axonal

regeneration in vivo and in vitro. J Neurosci. 13:455–466.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Thanos S: The relationship of microglial

cells to dying neurons during natural neuronal cell death and

axotomy-induced degeneration of the rat retina. Eur J Neurosci.

3:1189–1207. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Teng P, Li YH, Cheng WJ, et al:

Neuroprotective effects of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides in

lipopolysaccharide-induced BV2 microglia cells. Mol Med Rep.

7:1977–1981. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rangarajan P, Eng-Ang L and Dheen ST:

Potential drugs targeting microglia: current knowledge and future

prospects. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 12:799–806. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shin EJ, Bach JH, Lee SY, Kim JM, Lee JJ,

Hong JS, et al: Neuropsychotoxic and neuroprotective potentials of

dextromethorphan and its analogs. J Pharmacol Sci. 116:137–148.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mousavi SA, Saadatnia M, Khorvash F,

Hoseini T and Sariaslani P: Evaluation of the neuroprotective

effect of dextromethorphan in the acute phase of ischaemic stroke.

Arch Med Sci. 7:465–469. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Liu B, Du L and Hong JS: Naloxone protects

rat dopaminergic neurons against inflammatory damage through

inhibition of microglia activation and superoxide generation. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 293:607–617. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu Y, Qin L, Wilson BC, et al: Inhibition

by naloxone stereoisomers of beta-amyloid peptide (1–42)-induced

superoxide production in microglia and degeneration of cortical and

mesencephalic neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 302:1212–1219. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chang RC, Rota C, Glover RE, Mason RP and

Hong JS: A novel effect of an opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone,

on the production of reactive oxygen species by microglia: a study

by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Brain Res.

854:224–229. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Liu B, Du L, Kong LY, et al: Reduction by

naloxone of lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity in mouse

cortical neuron-glia co-cultures. Neuroscience. 97:749–756. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu Y, Qin L, Li G, et al:

Dextromethorphan protects dopaminergic neurons against

inflammation-mediated degeneration through inhibition of microglial

activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 305:212–218. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li G, Liu Y, Tzeng NS, et al: Protective

effect of dextromethorphan against endotoxic shock in mice. Biochem

Pharmacol. 69:233–240. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hansen JJ, Bross P, Westergaard M, et al:

Genomic structure of the human mitochondrial chaperonin genes:

HSP60 and HSP10 are localised head to head on chromosome 2

separated by a bidirectional promoter. Hum Genet. 112:71–77. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lin L, Kim SC, Wang Y, Gupta S, et al:

HSP60 in heart failure: abnormal distribution and role in cardiac

myocyte apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

293:H2238–H2247. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kreutzberg GW: Microglia: a sensor for

pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 19:312–318. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Park E, Kim DY and Chun HS: Resveratrol

inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced phagocytotic activity in BV2

cells. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 55:803–807. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Karlstetter M, Lippe E, Walczak Y, et al:

Curcumin is a potent modulator of microglial gene expression and

migration. J Neuroinflammation. 8:1252011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Park HY, Han MH, Park C, et al:

Anti-inflammatory effects of fucoidan through inhibition of NF-κB,

MAPK and Akt activation in lipopolysaccharide-induced BV2 microglia

cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 49:1745–1752. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Britton P, Lu XC, Laskosky MS and Tortella

FC: Dextromethorphan protects against cerebral injury following

transient, but not permanent, focal ischemia in rats. Life Sci.

60:1729–1740. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lesage AS, De Loore KL, Peeters L and

Leysen JE: Neuroprotective sigma ligands interfere with the

glutamate-activated NOS pathway in hippocampal cell culture.

Synapse. 20:156–164. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Prince DA and Feeser HR: Dextromethorphan

protects against cerebral infarction in a rat model of

hypoxia-ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 85:291–296. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Berman FW and Murray TF: Characterization

of [3H]MK-801 binding to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors

in cultured rat cerebellar granule neurons and involvement in

glutamate-mediated toxicity. J Biochem Toxicol. 11:217–226. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Craviso GL and Musacchio JM: High-affinity

dextromethorphan binding sites in guinea pig brain. I Initial

characterization. Mol Pharmacol. 23:619–628. 1983a.

|

|

32

|

Craviso GL and Musacchio JM: High-affinity

dextromethorphan binding sites in guinea pig brain. II Competition

experiments. Mol Pharmacol. 23:629–640. 1983b.

|

|

33

|

Khasnavis S, Jana A, Roy A, et al:

Suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation and inflammation in

microglia by physically modified saline. J Biol Chem.

287:29529–29542. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gu JH, Ge JB, Li M, et al: Inhibition of

NF-κB activation is associated with anti-inflammatory and

anti-apoptotic effects of Ginkgolide B in a mouse model of cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharm Sci. 47:652–660. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Woods DC, White YA, Dau C and Johnson AL:

TLR4 activates NF-κB in human ovarian granulosa tumor cells.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 409:675–680. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Soria JA, Arroyo DS, Gaviglio EA, et al:

Interleukin 4 induces the apoptosis of mouse microglial cells by a

caspase-dependent mechanism. Neurobiol Dis. 43:616–624. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Burguillos MA, Deierborg T, Kavanagh E, et

al: Caspase signalling controls microglia activation and

neurotoxicity. Nature. 472:319–324. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kim SC, Stice JP, Chen L, et al:

Extracellular heat shock protein 60, cardiac myocytes and

apoptosis. Circ Res. 105:1186–1195. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wang Y, Chen L, Hagiwara N and Knowlton

AA: Regulation of heat shock protein 60 and 72 expression in the

failing heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 48:360–366. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

40

|

Kröncke KD, Fehsel K and Kolb-Bachofen V:

Inducible nitric oxide synthase and its product nitric oxide, a

small molecule with complex biological activities. Biol Chem Hoppe

Seyler. 376:327–343. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|