Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently

diagnosed types of cancer in females (1). The risk factors for breast cancer are

age, alcohol consumption, body mass index, hormone replacement

therapy and reproductive factors (2). The majority of females with breast

cancer develop metastasis in common sites, including the bone,

liver and lung (3). Several

reports have revealed that males are also susceptible to breast

cancer in the United States (4).

The progression of breast cancer between an estrogen-dependent,

non-metastatic phenotype and an estrogen-independent, invasive,

metastatic phenotype are accompanied by chemoresistance (5). Treatment for breast cancer includes

several approaches, including surgical and/or pharmacological

approaches by estrogenic signaling in estrogen receptor-positive

breast cancers (6). However, there

is no targeted therapy for estrogen-independent breast cancer

(7). Several studies have

investigated combination therapies to improve the response to

chemotherapy (8,9).

Continuous exposure of cancer cells to drugs leads

to the development of a multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype. The

resistance of multiple chemotherapeutic drugs has been recognized

as a major contributor to the failure of cancer therapy and

obstacle in the successful treatment of numerous types of

malignancy (10). MDR occurs

through several mechanisms, including increased adenosine

triphosphate (ATP)-dependent efflux (11). The classical cellular mechanism of

MDR involves efflux of the drug by various membrane transport

proteins. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are a family of

proteins, which mediate MDR via ATP-dependent drug efflux pumps

(12). Several transport proteins

of the ABC superfamily have been characterized and include

P-glycoprotein (P-gp, MDR-1; ABCB-1), multidrug

resistance-associated protein-1 (MRP-1; ABCC-1) and breast cancer

resistance protein (BCRP; ABCG-2) which are overexpressed in

chemoresistant cells (13).

Ionophore is a lipid-soluble molecule, which is

usually produced by a variety of microbes to transport ions across

biological membranes and increase the feeding efficiency of

ruminant animals (14,15). Salinomycin is one of the

monocarboxylic ionophores isolated from Streptomyces albus

(16). Salinomycin has been

demonstrated to cause the death of breast cancer stem cells (CSCs)

more efficiently compared with the anticancer drug, paclitaxel

(17). Several reports have

suggested that salinomycin induces apoptosis via cell cycle arrest

and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated mitochondrial pathways

in a diversity of cancer cells (18,19).

Salinomycin also triggers apoptosis by overcoming ABC

transporter-mediated multidrug and apoptosis resistance in MDR

cancer cells (20). Other reports

have indicated that salinomycin induces apoptosis through the

overexpression of B-cell lymphoma 2 and enhanced proteolytic

activity, independent of the p53 tumor suppressor protein in MDR

cancer cells (18).

Salinomycin-induced activation of autophagy, with concomitant

generation of ROS and activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress

has also been observed in human cancer cells (21,22).

The effect of salinomycin on the death of CSCs and MDR types of

cancer may demonstrate a novel class of anticancer agents. In the

present study, it was hypothesized that salinomycin may act as a

reverser of MDR and benefit patients receiving chemotherapy. The

reversal effect of salinomycin was investigated and the underlying

mechanism of action was evaluated in human breast cancer

doxorubicin-sensitive MCF-7 and doxorubicin-resistant MCF-7/MDR

cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Salinomycin, doxorubicin and

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-etrazolium bromide (MTT)

were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The

salinomycin and doxorubicin were dissolved in methanol (Samchun

Pure Chemical, Pyeongtaek, Korea) and distilled water as 20 mM

stock solutions, respectively. Antibodies for MDR-1, MRP-1 and

β-actin were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY,

USA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA),

respectively. Gat-anti-mouseimmunoglobulin (Ig)G was purchased from

Enzo Life Sciences. The ECL Western kit was purchased from GE

Healthcare Bio-Sciences (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Cell lines and cell culture

The MCF-7 human breast cancer cells lines were

obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

The MCF-7/MDR cell lines were generated through sequential exposure

to increasing concentrations of doxorubicin (0.1–1 µM). The

cells were maintained and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s

medium (DMEM; WelGENE Inc., Daegu, Republic of Korea), supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; WelGENE Inc.), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (WelGENE Inc.) at a

temperature of 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%

CO2. Doxorubicin (1 µM) was added to the culture

medium to maintain the MDR characteristics of the MCF-7/MDR

cells.

Cell viability analysis

The doxorubicin-sensitive MCF-7 and

doxorubicin-resistant MCF-7/MDR cells were seeded at a density of

1×104 cells/well into a 6-well plate. The cells were

treated with doxorubicin (0.1–20 µM) and salinomycin (0.5–20

µM), either alone or in combination for 72 h. Subsequently,

MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the culture medium for a

further 4 h incubation in a 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere.

The cells were then dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Junsei

Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Colorimetric analysis was performed at

570 nm using an ELISA reader (VERSAmax microplate reader; Molecular

Devices, Toronto, ON, Canada).

Intracellular accumulation of

doxorubicin

Doxorubicin is a well-known P-gp substrate and is

frequently used to treat breast cancer. In the present study, the

MCF-7/MDR cells were seeded at a density of 5×104 cells

in a glass-bottom dish. The cells were treated with 10 µM

doxorubicin, alone or in combination with salinomycin (10–20

µM). Following 3 h incubation at 37°C, the cells were washed

three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To determine

changes in the efflux of intracellular doxorubicin, a separate set

of samples was incubated for 2 h at 37°C in fresh medium without

doxorubicin or salinomycin, as a control. The cells were visualized

using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview

FV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). To quantify the intracellular

accumulation of doxorubicin, the cells were exposed to doxorubicin,

alone or in combination with salinomycin for 3 h at 37°C. The

control samples were incubated without doxorubicin or salinomycin,

or with salinomycin (10–20 µM) alone for 2 h at 37°C. The

cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (FACScalibur; Becton

Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and the accumulation of

doxorubicin was calculated using Cell Quest Pro software on

Mac®OS 9 (Becton Dickinson).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The MCF-7/MDR cells were seeded into 60

cm2 cell culture dishes (1×106 cells).

Following 24 h incubation at 37°C, the cells were treated with

salinomycin (10 or 20 µM) for 3 and 6 h. Subsequently, the

cells were harvested, and total RNA isolation was performed using a

RiboEX_column Total RNA Purification kit (GeneAll, Seoul, Korea).

RT-qPCR amplification was performed using primers for MDR1, MRP1

and GAPDH. The PCR primers were designed using the Primer3 programs

(http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) and the sequences were

as follows: MDR1, forward 5′-ATATCAGCAGCCCACATCAT-3′ and reverse

5′-GAAGCACTGGGATGTCCGGT-3′; MRP1, forward

5′-TGTGAGCTGGTCTCTGCCATA-3′ and reverse 5′-CTGGCTCATGCCTGGACTCT-3′

and GAPDH, forward 5′-GCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3′ and reverse

5′-GTAGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′. The PCR cycles were as follows: 94°C

for 5 min; 33 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min and 72°C for

1 min; followed by 72°C for 10 min. For The RT-qPCR was performed

using low cycle numbers to avoid saturation, in triplicate

samples.

Western blot analysis

The cell extracts were prepared by incubating the

cells in lysis buffer, containing 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4),

5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mg/ml aprotinin,

50 µg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM benzidine and 1 mg/ml pepstatin.

Equal quantities of proteins (40 µg) were

electrophoretically separated using sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on an 8% gel,

and were then transferred onto a polyvinylidenefluoride (PVDF)

membrane (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). Following blocking with

Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 20 mM Tris

(pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20, with5% skim milk, the

membranes were incubated with primary (MDR-1, MRP-1 and β-actin;

1:1,000; 4°C overnight) and secondary (goat-anti-mouse; 1:5,000, 2

h at room temperature) antibodies. The membranes were then washed

with TBS-T buffer and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence

western blotting detection reagents. The density of each band was

determined using a fluorescence scanner (LAS 3000; FujiFilm, Tokyo,

Japan) and analyzed using Multi Gauge V3.0 software (FujiFilm).

Statistical analysis

The experiments were repeated at least three times

with consistent results. Unless otherwise stated, the data are

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Analysis of variance

was used to compare the experimental groups with the control group,

whereas comparisons among multiple groups were performed by Tukey’s

multiple comparison test using Graphpad InStat V3.05. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Salinomycin sensitizes MCF-7/MDR cells

against doxorubicin

The effect of salinomycin on cytotoxicity was

investigated using an MTT assay on the doxorubicin-sensitivite

MCF-7 or doxorubicin-resistant MCF-7/MDR cells. Following treatment

with various concentrations of doxorubicin for 72 h, the viability

of cells against MCF-7 was reduced in a dose-dependent manner. The

half maximal inhibitory concentration of doxorubicin was <1

µM. By contrast, the MCF-7/MDR cells were highly resistant

to doxorubicin (Fig. 1A). In

addition, salinomycin significantly inhibited cell viability in the

MCF-7 cells, however MCF-7/MDR cells exhibited only mild

cytotoxicity compared with the MCF-7 cells when the cells were

exposed to salinomycin alone, at the levels up to 20 µM

(Fig. 1B). Salinomycin

significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin on the

MCF-7/MDR cells in the dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). In the presence of 10 µM

salinomycin, the viabilities of these cells following 72 h

treatment with 10 or 20 µM doxorubicin were 19.4 and 18.2%,

respectively, However, in the presence of 20 µM salinomycin,

the viabilities at the same concentrations of doxorubicin were 12.4

and 8.1%, respectively. No significant effects of salinomycin on

doxorubicin cytotoxicity were observed on the MCF-7 cells (data not

shown).

Salinomycin increases doxorubicin

accumulation and decreases efflux in MCF-7/MDR cells

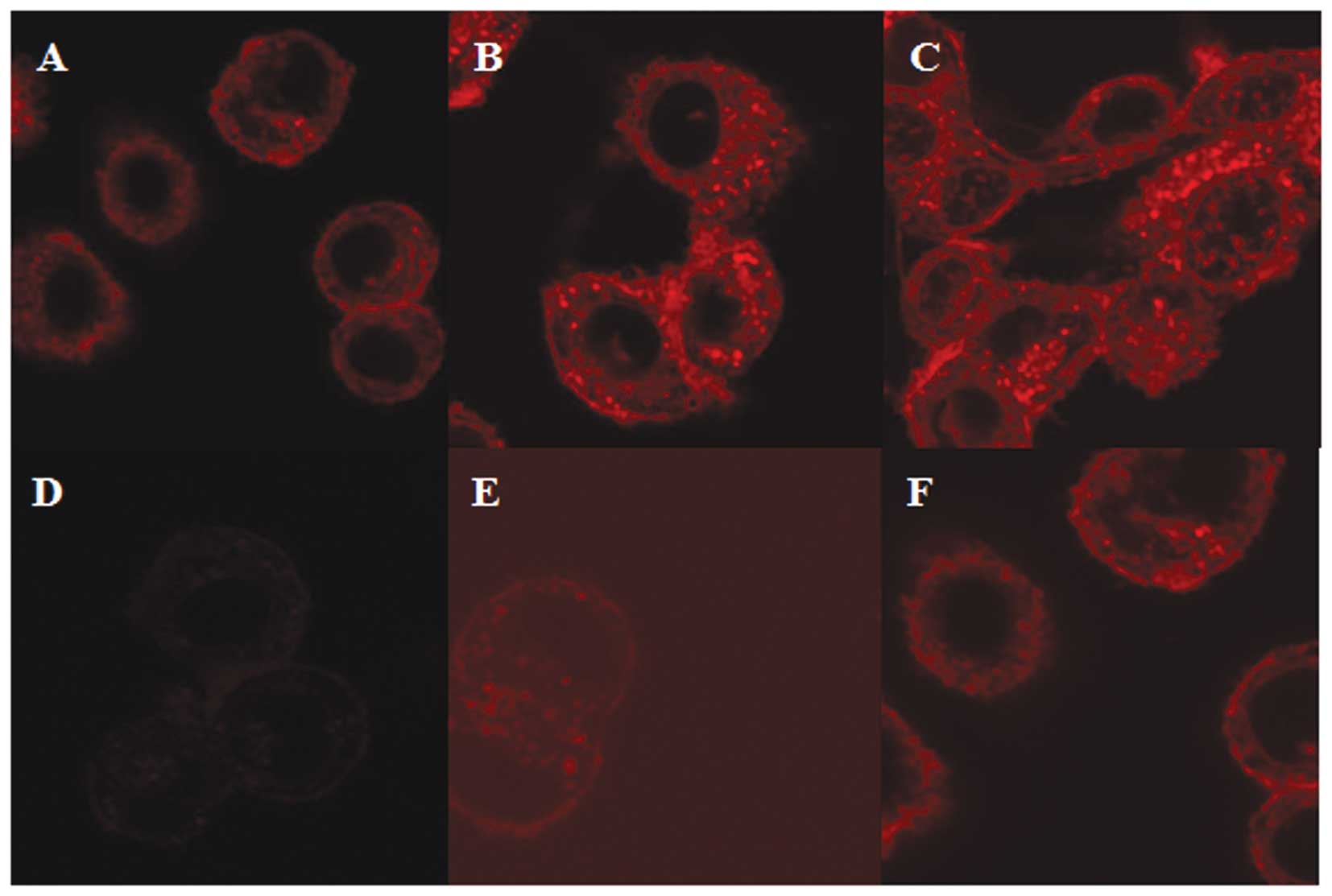

The intracellular localization and accumulation of

doxorubicin in the MCF-7/MDR cells were observed using laser

scanning confocal microscopy. Red fluorescence was observed in the

cells (Fig. 2A) following

treatment with 10 µM doxorubicin alone for 3 h. The

fluorescence observed following treatment with the combination of

either 10 or 20 µM doxorubicin with salinomycin led to a

marginal increase in the accumulation of doxorubicin, and was

dependent on the salinomycin concentration (Fig. 2B and C). At 2 h post-removal of

doxorubicin and salinomycin, the fluorescence of the cytoplasmic

signal in the control cells treated with doxorubicin alone was

almost absent following its removal (Fig. 2D), however, the fluorescence

remained evident in the cells pretreated with salinomycin (Fig. 2E and F). These results were

consistent with the cell viability data, indicating that

salinomycin induced the efflux of doxorubicin from the cells.

Salinomycin regulates the cellular uptake

and efflux of doxorubicin in MCF-7/MDR cells

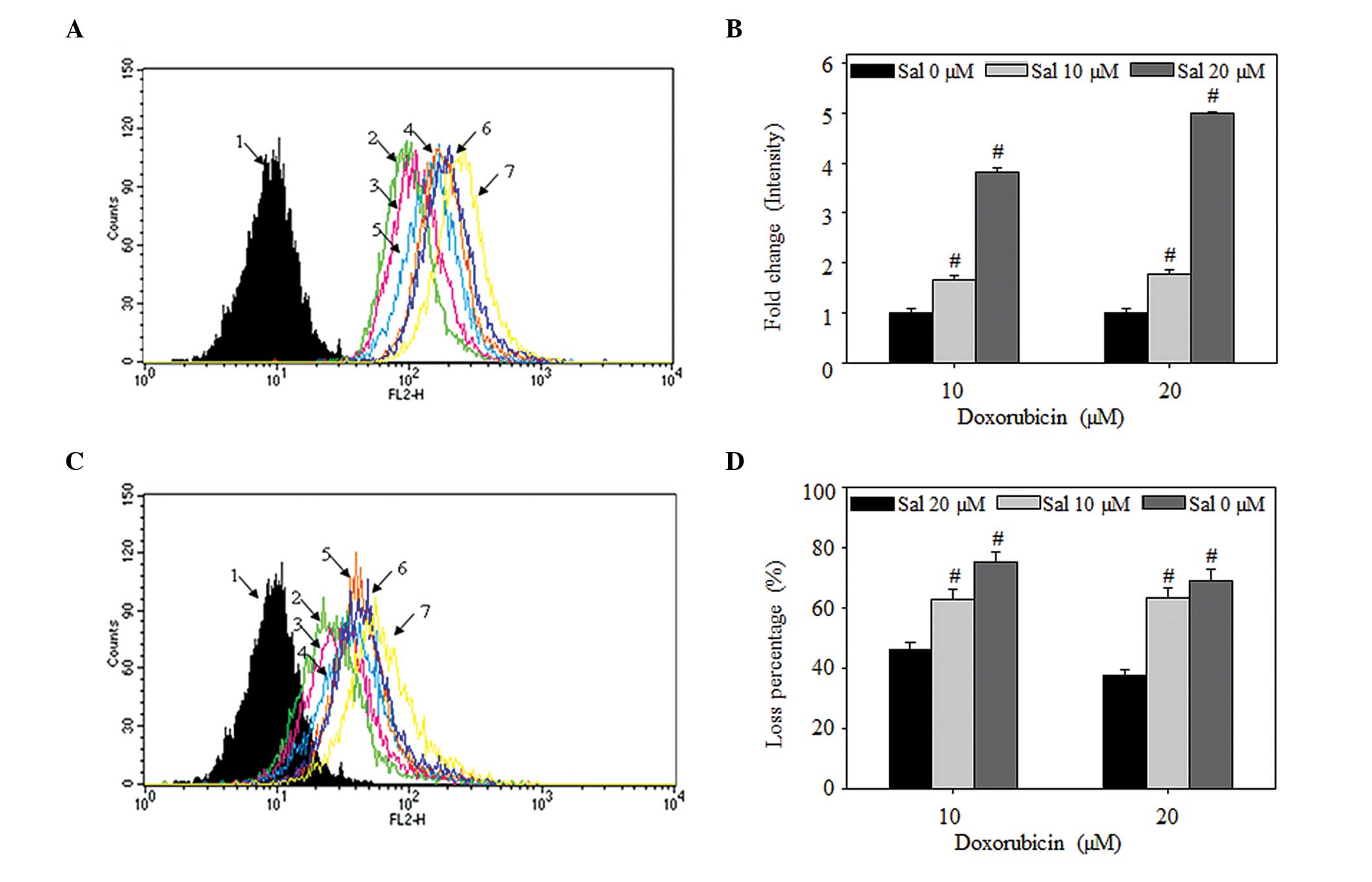

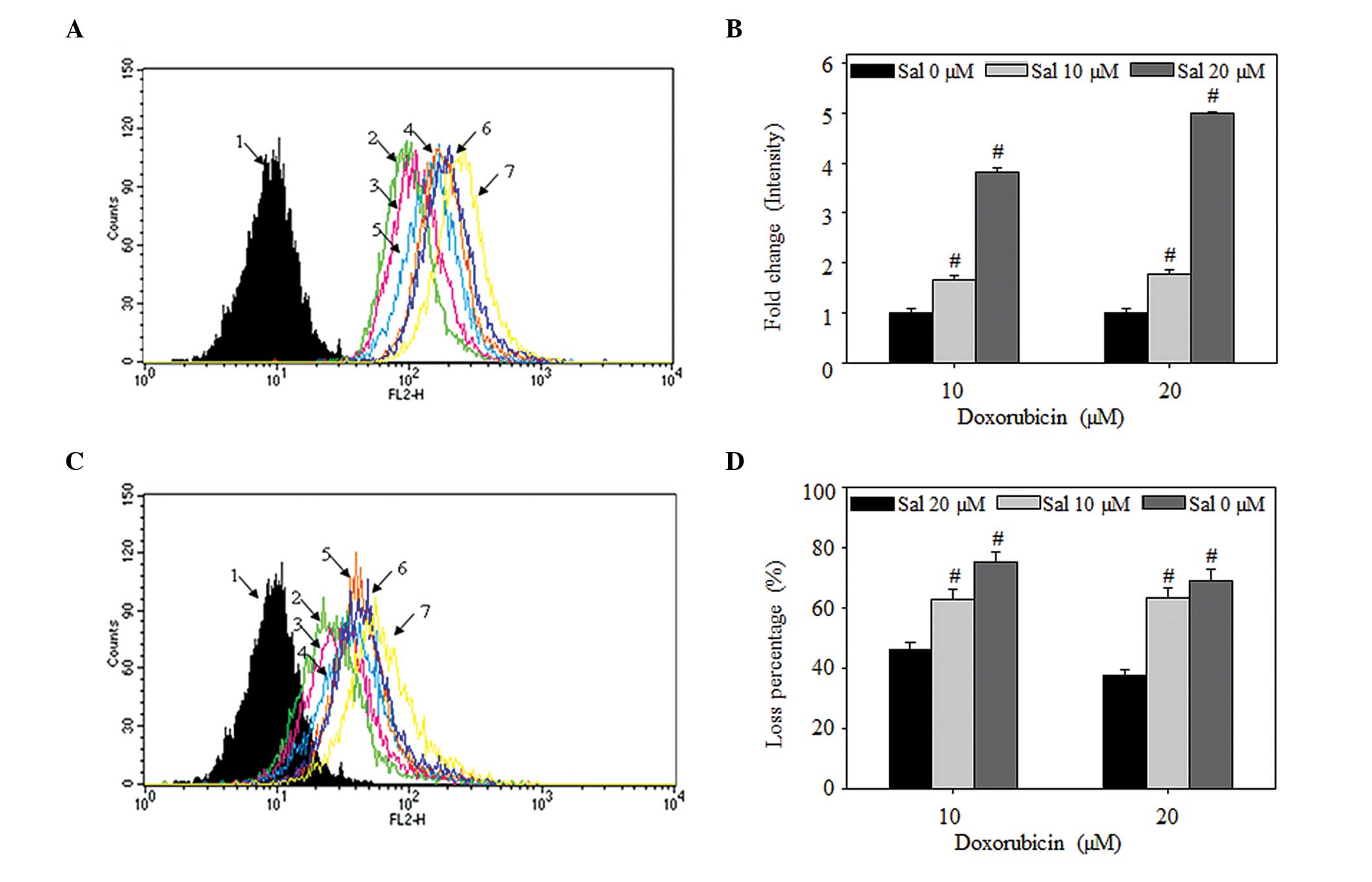

To determine whether salinomycin mediated the net

uptake and efflux of doxorubicin in the MCF-7/MDR cells, the flow

cytometric intensities were analyzed. These results demonstrated

significant increases, similar to those observed using confocal

microscopy, in the net uptake of doxorubicin, and decreased efflux

of doxorubicin by salinomycin (Fig. 3A

and B). In the case of net uptake, at 3 h post-treatment of the

MCF-7/MDR cells with 10 µM doxorubicin with either 10 or 20

µM salinomycin, the fluorescence signal intensities were

1.6- or 3.8-fold higher, respectively, compared with treatment with

10 µM doxorubicin alone. Following treatment with 20

µM doxorubicin with either 10 or 20 µM salinomycin,

the intensities were 1.7- and 4.9-fold higher, respectively,

compared with treatment with 20 µM doxorubicin alone.

| Figure 3Salinomycin regulates the uptake and

efflux of doxorubicin in MCF-7/MDR cells. (A and B) Effects of

salinomycin on the accumulation of doxorubicin. The MCF-7/MDR cells

were treated with doxorubicin, alone or in combination with

salinomycin (10 or 20 µM) for 3 h. (C and D) Effects of

salinomycin on the efflux of doxorubicin. The cells were removed

from exposure to doxorubicin, but not salinomycin, for 2 h. (A and

C) Flow cytometric analysis. 1, untreated; 2, doxorubicin (10

µM); 3, doxorubicin (10 µM) + salinomycin (10

µM); 4, doxorubicin (10 µM) + salinomycin (20

µM); 5, doxorubicin (20 µM); 6, doxorubicin (20

µM) + salinomycin (10 µM); 7, doxorubicin (20

µM) + salinomycin (20 µM). All data are

representative of at least three times independent experiment(B)

Fold change in the intracellular fluorescent intensity. (D)

Percentage loss of intracellular fluorescent intensity.. Data in B

and D are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

(#P<0.05). MDR, multidrug resistance; Sal,

salinomycin. |

In terms of the efflux of intracellular doxorubicin

following removal of the drug from the culture media, the

intracellular signal loss was significantly lower in the cells

treated with a combination of doxorubicin and salinomycin, compared

with that of the cells treated with doxorubicin alone (Fig. 3C and D). Compared with the signal

prior to drug removal, the losses in intracellular doxorubicin 2 h

post-treatment were 75.1 and 69.3% following 3 h treatment with 10

or 20 µM doxorubicin, respectively. The losses in

intracellular doxorubicin were only 63.0 and 46.1% following

treatment with 10 or 20 µM salinomycin, compared with those

observed following combined treatment with salinomycin and 10

µM doxorubicin, respectively. In the cells treated with a

combination of salinomycin and 20 µM doxorubicin, the 63.3%

loss of intracellular doxorubicin was reduced to 37.5%. These

results demonstrated that salinomycin enhanced doxorubicin-induced

cytotoxicity by increasing the influx of doxorubicin and decreasing

the efflux of doxorubicin in the MCF-7/MDR cells.

Salinomycin regulates efflux and influx

independently of the gene and protein expression levels of MDR1 and

MRP1 in MCF-7/MDR cells

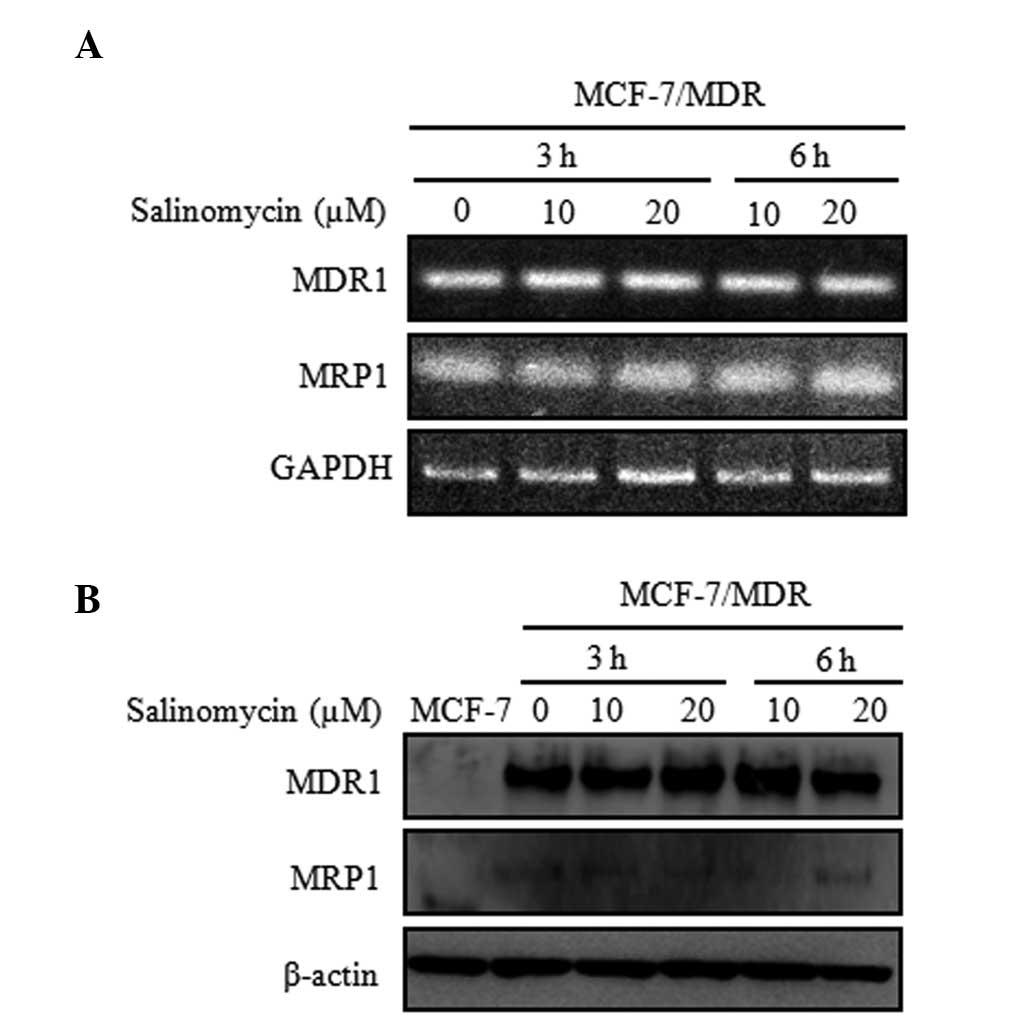

To determine the mechanism underlying the reversal

effect of salinomycin on the resistance of cancer cells, the

present study examined the mRNA and protein expression levels of

MDR1 and MRP1 in the MCF-7 and MCF-7/MDR cells. The mRNA and

protein levels were estimated using RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis. Following treatment with salimycin (10 or 20 µM)

for 3 and 6 h, no significant changes were detected in either the

mRNA or protein expression levels (Fig. 4), compared with the cells not

exposed to salinomycin. However, the MDR1 and MRP1 proteins were

not detected in the MCF-7 cells. These results support the

suggested that salinomycin did not affect the mRNA and protein

expression levels of MDR1 and MRP1 mRNA and protein.

Discussion

MDR in cancer cells is a significant cause of

failure in the chemotherapeutic treatment of several types of

cancer (23). MDR involves

cross-resistance to unassociated compounds by exposure to an

anticancer agent (24). MDR cancer

cells often exhibit elevated abilities of increased efflux

(ATP-dependent efflux pumps) or decreased influx. The development

of MDR is mediated by different mechanisms, and conventional

resistance to anticancer drugs has been linked predominantly to the

overexpression of ABC transporters, including P-gp, multi-drug

resistance-associated protein-1 and the breast cancer resistance

protein (12).

Doxorubicin is an anthracycline antibiotic and is

commonly used as an effective agent inthe treatment of several

types of cancer, including bladder, breast and stomach cancer and

multiple myeloma (25). Notably,

the resistance of drugs, including doxorubicin, cisplatin and

vinblastine, represents a major obstacle in the successful

treatment of MDR cancer (26).

There have been several reports on the use of doxorubicin in

combination with certain other drugs, including fluorouracil and

cyclophosphamide (27). The

identification of novel combination drugs, which correlate with

treatment response, has the potential to improve the success of MDR

cancer therapy.

Salinomycin is an ionophore, which is used as a

therapeutic antibacterial and coccidiostat (16). A previous study reported that

salinomycin causes breast cancer stem cell death, by screening

16,000 different chemical compounds targeting cancer stem cell

metastasis and relapse (17). In

our previous study, salinomycin was observed to induce apoptosis

via the ROS-mediated mitochondrial pathway (19). Other studies have supported these

results in variety of cancer cells (23). It has also been demonstrated that

salinomycin, as P-gp inhibitors, exhibit potent antiproliferative

activity against MDR cancer cells (20).

The present study hypothesized that salinomycin may

effectively inhibit binding with P-gp and thus decrease the efflux

of anticancer agents from the MDR cancer cells. To investigate

this, doxorubicin-resistant MCF-7/MDR cells were treated with

doxorubicin, alone or in combination with salinomycin, to assess

cell viability. The results revealed the enhancement of

salinomycin-mediated cytotoxicity in the MCF-7/MDR cells. This

finding was consistent with those of the confocal microscope

analysis, in which the doxorubicin fluorescent signals of the

salinomycin-treated cells were higher compared with those in the

cells treated with doxorubicin alone. In several previous studies,

salinomycin has been revealed as a substrate with increased

P-gp-dependent transport in MDR cancer cells, as evidenced through

drug efflux assays in MDR cancer cell lines (28). Use of a conformational P-gp assay

in a previous study provided evidence that the inhibitory effect of

salinomycin on P-gp function may be mediated by the induction of

ATP transporter conformational change (28). Using flow cytometric analysis, the

present study confirmed that salinomycin significantly increased

the net cellular uptake and decreased the cellular efflux of

doxorubicin. Even 2 h following the removal of doxorubicin and

salinomycin, the efflux rate of intracellular doxorubicin remained.

Another important feature of salinomycin is that it facilitates

bidirectional ion flux through the lipid barrier of membranes,

acting as channel blockers to inhibit cell proliferation (29). A similar competitive mechanism has

been observed in the reversal of MDR by P-gp inhibitors, including

verapamil and cyclosporine A (30,31).

In the present study, an efflux was examined using RT-qPCR and

western blot analysis, to determine whether this accumulation

effect was directly associated with the gene and protein expression

of MDR1 and MRP. The expression levels of MDR-1 and MRP-1 were not

altered at either the mRNA or protein levels in the cells treated

with salinomycin. These results indicated that salinomycin was

mediated by its ability to promote the increased uptake and

decreased efflux of doxorubicin in the MCF-7/MDR cells.

In analyzing the resistance of MCF-7/MDR cells

treated with doxorubicin, the present study demonstrated that

salinomycin was a significant inhibitor, with a reversal effect on

the resistance of cancer cells. When used in combination with

chemotherapeutic agents in MDR cancer, salinomycin may have

beneficial therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Basic Science

Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea

(NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning

(grant. no. NRF-2012R1A1A2022587) and an NRF grant funded by the

Korea Government (grant. no. 2012R1A1 A4A01019016).

References

|

1

|

Siegel R, Naishadham D and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 63:11–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Singletary SE: Rating the risk factors for

breast cancer. Ann Surg. 237:474–482. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Berman AT, Thukral AD, Hwang WT, Solin LJ

and Vapiwala N: Incidence and patterns of distant metastases for

patients with early-stage breast cancer after breast conservation

treatment. Clin Breast Cancer. 13:88–94. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins

G and Hortobagyi GN: Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based

study. Cancer. 101:51–57. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Prat A and Perou CM: Deconstructing the

molecular portraits of breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 5:5–23. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nilsson S, Koehler KF and Gustafsson JA:

Development of subtype-selective oestrogen receptor-based

therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 10:778–792. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Foulkes WD, Smith IE and Reis-Filho JS:

Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 363:1938–1948. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Higgins MJ and Baselga J: Targeted

therapies for breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 121:3797–3803. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim TH, Shin YJ, Won AJ, Lee BM, Choi WS,

Jung JH, Chung HY and Kim HS: Resveratrol enhances chemosensitivity

of doxorubicin in multidrug-resistant human breast cancer cells via

increased cellular influx of doxorubicin. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1840:615–625. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ullah MF: Cancer multidrug resistance

(MDR): a major impediment to effective chemotherapy. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 9:1–6. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gottesman MM, Fojo T and Bates SE:

Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters.

Nat Rev Cancer. 2:48–58. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sharom FJ: ABC multidrug transporters:

structure, function and role in chemoresistance. Pharmacogenomics.

9:105–127. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Choudhuri S and Klaassen CD: Structure,

function, expression, genomic organization, and single nucleotide

polymorphisms of human ABCB1 (MDR1), ABCC (MRP), and ABCG2 (BCRP)

efflux transporters. Int J Toxicol. 25:231–259. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pressman BC: Antibiotic models for

carrier-mediated transport through membranes. Antimicrob. Agents

Chemother (Bethesda). 9:28–34. 1969.

|

|

15

|

Rutkowski J and Brzezinski B: Structures

and properties of naturally occurring polyether antibiotics. Biomed

Res Int. 2013:1–31. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Naujokat C, Fuchs D and Opelz G:

Salinomycin in cancer: A new mission for an old agent. Mol Med Rep.

3:555–559. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Gupta PB, Onder TT, Jiang G, Tao K,

Kuperwasser C, Weinberg RA and Lander ES: Identification of

selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput

screening. Cell. 138:645–659. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Al Dhaheri Y, Attoub S, Arafat K, Abuqamar

S, Eid A, Al Faresi N and Iratni R: Salinomycin induces apoptosis

and senescence in breast cancer: upregulation of p21,

downregulation of survivin and histone H3 and H4 hyperacetylation.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1830:3121–3135. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kim KY, Yu SN, Lee SY, Chun SS, Choi YL,

Park YM, Song CS, Chatterjee B and Ahn SC: Salinomycin-induced

apoptosis of human prostate cancer cells due to accumulated

reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial membrane depolarization.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 413:80–86. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fuchs D, Daniel V, Sadeghi M, Opelz G and

Naujokat C: Salinomycin overcomes ABC transporter-mediated

multidrug and apoptosis resistance in human leukemia stem cell-like

KG-1a cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 394:1098–1104. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Verdoodt B, Vogt M, Schmitz I, Liffers ST,

Tannapfel A and Mirmohammadsadegh A: Salinomycin induces autophagy

in colon and breast cancer cells with concomitant generation of

reactive oxygen species. PLoS One. 7:e441322012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yoon MJ, Kang YJ, Kim IY, Kim EH, Lee JA,

Lim JH, Kwon TK and Choi KS: Monensin, a polyether ionophore

antibiotic, overcomes TRAIL resistance in glioma cells via

endoplasmic reticulum stress, DR5 upregulation and c-FLIP

downregulation. Carcinogenesis. 34:1918–1928. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wu CP, Calcagno AM and Ambudkar SV:

Reversal of ABC drug transporter-mediated multidrug resistance in

cancer cells: evaluation of current strategies. Curr Mol Pharmacol.

1:93–105. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Thomas H and Coley HM: Overcoming

multidrug resistance in cancer: an update on the clinical strategy

of inhibiting p-glycoprotein. Cancer Control. 10:159–165.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Rahman AM, Yusuf SW and Ewer MS:

Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and the cardiac-sparing effect

of liposomal formulation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2:567–583. 2007.

|

|

26

|

Liu Y, Liu H, Han B and Zhang JT:

Identification of 14-3-3sigma as a contributor to drug resistance

in human breast cancer cells using functional proteomic analysis.

Cancer Res. 66:3248–3255. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Vulsteke C, Lambrechts D, Dieudonné A, et

al: Genetic variability in the multidrug resistance associated

protein-1 (ABCC1/MRP1) predicts hematological toxicity in breast

cancer patients receiving (neo-) adjuvant chemotherapy with

5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC). Ann Oncol.

24:1513–1525. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Riccioni R, Dupuis ML, Bernabei M,

Petrucci E, Pasquini L, Mariani G, Cianfriglia M and Testa U: The

cancer stem cell selective inhibitor salinomycin is a

p-glycoprotein inhibitor. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 45:86–92. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Le Guennec JY, Ouadid-Ahidouch H, Soriani

O, Besson P, Ahidouch A and Vandier C: Voltage-gated ion channels,

new targets in anti-cancer research. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug

Discov. 2:189–202. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Tsubaki M, Komai M, Itoh T, Imano M,

Sakamoto K, Shimaoka H, Takeda T, Ogawa N, Mashimo K, Fujiwara D,

Mukai J, Sakaguchi K, Satou T and Nishida S: By inhibiting Src,

verapamil and dasatinib overcome multidrug resistance via increased

expression of Bim and decreased expressions of MDR1 and survivin in

human multidrug-resistant myeloma cells. Leuk Res. 38:121–130.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

De Souza PS, da Cunha Vasconcelos F, Silva

LF and Maia RC: Cyclosporine A enables vincristine-induced

apoptosis during reversal of multidrug resistance phenotype in

chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Tumour Biol. 33:943–956. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|