Introduction

Liver fibrosis is a reversible wound-healing

response that is characterized by increased and altered deposition

of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the liver (1). This process is rigorously controlled

by several growth factors and cytokines (2–5). Of

these, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is the most potent factor

in stimulating type I collagen gene transcription, which is the

predominant ECM component of fibrotic tissue (6).

N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporine (NIM811) is a

derivative of cyclosporine, but does not exhibit an

immunosuppressive effect. NIM811 inhibits the expression of the

mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT) pore protein in

hepatocytes, which results in hepatocyte cytoprotection (7–10).

It also suppresses hepatic stellate cell (HSC) proliferation and

collagen production, as well as stimulating collagenase activity

in vitro (11). These

findings indicate that NIM811 is a potential candidate for

antifibrosis therapy. Indeed, it was found previously that NIM811

attenuates liver fibrosis and inflammation in rats with

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (12). Therefore, in the present study, the

TGF-β signaling pathway was analyzed with the aim of elucidating

the molecular mechanism underlying the effects of NIM811 in rats

with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and cultured HSC-T6

cells.

Materials and methods

Animal study

Liver samples were obtained from control rats and

rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, with or without

NIM811 treatment. These liver samples were collected by Dr Hui

Wang. NIM811 was a gift from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Male

Wistar rats weighing 230–260 g were obtained from Beijing Vital

River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Liver fibrosis was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 0.2

ml/100 g body weight of 40% CCl4/corn oil twice weekly.

Rats were also treated with different doses of NIM811 (low dose, 10

mg/kg/day; and high dose, 20 mg/kg/day) by gavage for 6 weeks as

previously reported (13). All

protocols and procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use

Committee of Capital Medical University (Beijing, China). The

animals were housed in an air-conditioned room at 23–25°C with a 12

h dark/light cycle for 1 week prior to initiation of the

experiment. All animals received humane care during the study with

unlimited access to chow and water.

Cell culture

The HSC-T6 cell line was provided by Dr Scott L.

Friedman (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA) and

was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM;

Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal

calf serum (FCS; Gibco Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The

cell viability of HSCs was >90% at 24 h in the presence of 2

µM NIM811 in DMEM under serum-free conditions, thus

concentrations of 0.5, 1 and 2 µM were used. After serum

starvation for 16 h, HSC-T6 cells were treated with NIM811 (0.5, 1

or 2 µM), TGFβ1 (5 ng/ml) (14) or TGFβ1 (5 ng/ml) with NIM811 (0.5,

1 or 2 µM) in serum-free medium for 6, 12 or 18 h.

Determination of collagen I and TGF-β1 in

HSC-T6 cell supernatant

Cultured HSC-T6 cells were plated into 6-well cell

culture plates at a density of 105 cells/well and were

incubated in serum-free medium with 0, 0.5, 1 or 2 µM NIM811

for 18 h. Collagen I and TGF-β1 production was determined in the

culture medium using an ELISA (USCN Life Science Inc., Wuhan,

China) and immunoassay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA),

respectively.

mRNA levels of collagen I, α-smooth

muscle actin (SMA), TGF-β1 and TGF-β pathway downstream signaling

molecule-detection by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen rat liver

specimens and HSC-T6 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life

Technologies). The amount of RNA was quantified, and its quality

was verified by ultraviolet absorbance spectrophotometry at 260 and

280 nm (BioPhotometer® D30; Eppendorf North America

Inc., Hauppauge, NY, USA). cDNA was reversed transcribed using the

High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems,

Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The reaction conditions were as follows: 25°C for 10

min, 37°C for 150 min, 85°C for 5 sec, and 4°C for 5 min, prior to

chilling on ice. cDNA was stored at −20°C for future use.

Collagen I, α-SMA, TGF-β1, TβR-I, Smad1, Smad7 and

Id1 mRNA levels were quantified by RT-qPCR. The sequences of the

primers used are shown in Table I.

GAPDH, a housekeeping gene, was used as an internal control primer

for target genes. All primers were obtained from Invitrogen Life

Technologies (Beijing, China). The expression of mRNA was measured

by SYBR Green real-time PCR using an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied

Biosystems). PCR was performed in 20 µl buffer that

contained 2 µg cDNA, 1 µl each primer, and 10

µl SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems).

Comparative cycle quantification (Cq) calculations were all

relative to the control group. The expression of mRNA relative to

the control was derived using the equation 2−ΔΔCq.

| Table IPrimers for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis. |

Table I

Primers for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis.

| Gene | Primer

sequence | Product size

(bp) | Accession

number |

|---|

| GAPDH | F:

5′-CCTGCCAAGTATGATGACATCAAGA3′ | 75 | BC059110.1 |

| R:

5′-GTAGCCCAGGATGCCCTTTAGT3′ | | |

| Col I | F:

5′-CCTTTCTCCACCCCCTCTT-3′ | 69 | NM_053304.1 |

| R:

5′-TGTGTCTTTGGGGGAGACTT -3′ | | |

| α-SMA | F:

5′-TGCCATGTATGTGGCTATTCA-3′ | 61 | NM_001613.2 |

| R:

5′-ACCAGTTGTACGTCCAGAAGC-3 | | |

| TGF-β1 | F:

5′-CCTGGAAAGGGCTCAACAC-3′ | 100 | NM_021578.2 |

| R:

5′-CTGCCGTACACAGCAGTTCT-3′ | | |

| TβR-I | F:

5′-CACGATGAGCTGAGCCTGTA-3′ | 60 | NM_012775.2 |

| R:

5′-ACCCTGGAGTGCATGGTAAG-3′ | | |

| Smad1 | F:

5′-AGAAAGGGGCCATGGAAG-3′ | 78 | NM_013130.2 |

|

R:5′-AGCGAGGAATGGTGACACA-3′ | | |

| Smad7 | F:

5′-GGAGTCCTTTCCTCTCTC -3′ | 73 | NM_030858.1 |

| R:

5′-GGCTCAATGAGCATGCTCAC -3′ | | |

| Id1 | F:

5′-GCGAGATCAGTGCCTTGG-3′ | 123 | NM_012797.2 |

| R:

5′-TTTTCCTCTTGCCTCCTGAA-3′ | | |

Protein detection of α-SMA, TβR-I and

TGF-β pathway downstream signaling molecules by western

blotting

Protein was extracted from liver samples and HSC-T6

cells using a Protein Extractor IV (DBI, Shanghai, China),

homogenized, and assayed using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). Protein samples

(40 µg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (80 V for 40 min on a 5%

acrylamide stacking gel and 120 V for 70 min on a 10 or 15% running

gel), and then transferred (390 MA for 70 min or 80 V for 120 min)

to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C Extra Membrane 45; Amersham

Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The membranes were soaked in

Tris-buffered saline (10 mmol/l Tris-HCl and 250 mol/l NaCl) that

contained 5% non-fat powdered milk and 0.1% Tween-20 (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 2 h to block

non-specific sites. They were then incubated with primary antibody

overnight at 4°C in blocking solution. Antibody dilutions were as

follows: Rabbit anti-rat TβR-I (sc-9048) and Id1 (sc-488)

polyclonal antibodies (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.);

monoclonal mouse anti-rat α-SMA (SAB5500002) and β-actin

(SAB1403520) antibodies (1:1,000, 1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA); monoclonal rabbit anti-rat phosph-Smad2 (#3108),

phosph-Smad3 (#9520) and phosph-Smad1/5/8 (#13820) antibodies

(1:500, Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA, USA);

polyclonal rabbit anti-rat Smad7 antibodies (PA1-41506; 1:1,000;

Invitrogen Life Technologies); and horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-linked anti-rabbit (ZDR-5306) or anti-mouse (ZDR-5307) IgG

secondary antibodies (1:10,000; Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge

Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The resultant blots were

washed and incubated with HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary

antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was

visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific Inc.). Films (Kodak, Beijing, China) were scanned using

the Bio-Rad imaging system. Protein expression levels were

normalized to β-actin.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way

analysis of variance and unpaired Student's t-test as appropriate.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version

17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Effect of NIM811 on collagen I, α-SMA,

TGF-β1 and TβR-I expression in rats

RT-qPCR analysis showed that after treatment with

CCl4 for 6 weeks, collagen I mRNA expression increased

compared with that in normal rats, whereas NIM811 inhibited the

expression significantly (10 and 20 mg/kg, respectively; P<0.01;

Table II).

| Table IILevel of mRNA expression in rat liver

in 6 weeks. |

Table II

Level of mRNA expression in rat liver

in 6 weeks.

| mRNA | Normal (n=7) | CCl4

(n=8) | NIM811 (10 mg/kg)

(n=6) | NIM811 (20 mg/kg)

(n=7) |

|---|

| Col I | 1.0±0.4 | 92.0±4.6b | 38.6±7.8a | 40.9±2.4a |

| α-SMA | 1.0±0.3 | 60.5±4.6b | 18.3±2.2a | 16.3±3.0a |

| TGF-β1 | 1.0±0.1 | 8.6±0.2b | 3.0±0.6a | 3.4±0.5a |

| TβR-I | 1.0±0.2 | 1.9±0.3b | 1.0±0.2a | 0.9±0.2a |

| Id1 | 1.0±0.4 | 2.9±0.2b | 1.0±0.2a | 1.1±0.2a |

| Smad1 | 1.0±0.3 | 2.1±0.1b | 1.5±0.2a | 1.2±0.3a |

| Smad2 | 1.0±0.2 | 2.9±0.3b | 1.6±0.2a | 1.2±0.4a |

| Smad7 | 1.0±0.1 | 1.9±0.2b | 2.7±0.3a | 3.7±0.3a |

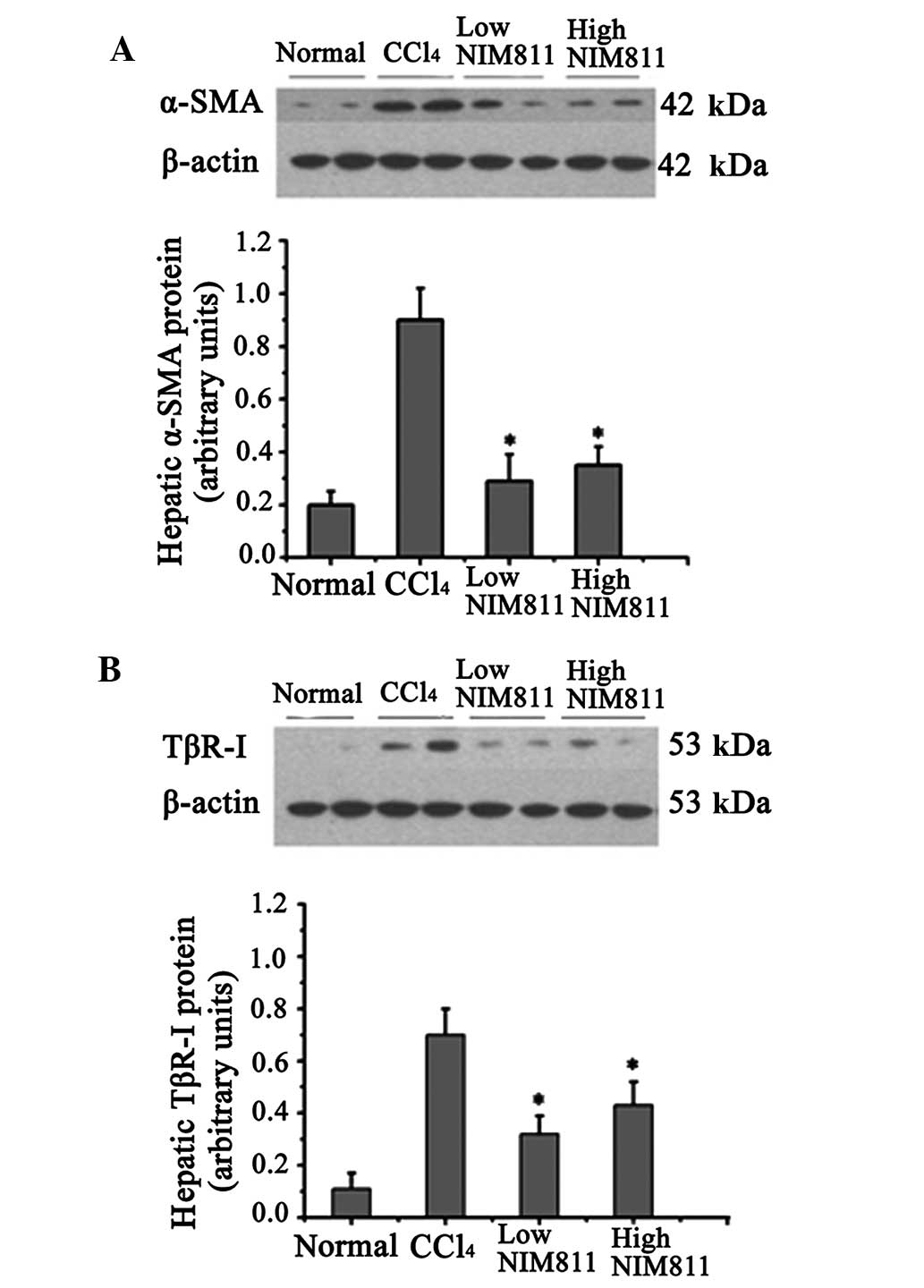

α-SMA mRNA expression in rats with liver fibrosis

was significantly increased compared with that in the normal

controls, and decreased significantly in the two NIM811-treated

groups (P<0.01) (Table II). In

the liver of rats with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis,

α-SMA protein expression increased significantly compared with

normal rats, whereas its expression was inhibited by NIM811

treatment (Fig. 1A).

The level of TGF-β1 and TβR-I mRNA increased after

CCl4 injection for 6 weeks and was blocked by NIM811

treatment (Table II). Similar to

mRNA expression, TβR-I protein was also reduced in the liver of

NIM811-treated rats compared with rats with CCl4-induced

liver fibrosis (Fig. 1B). These

results indicate that NIM811 inhibited liver fibrosis through the

TGF-β pathway.

Effect of NIM811 on TGF-β/anaplastic

lymphoma kinase (ALK)5 and TGF-β/ALK1 signaling pathway in rat

liver

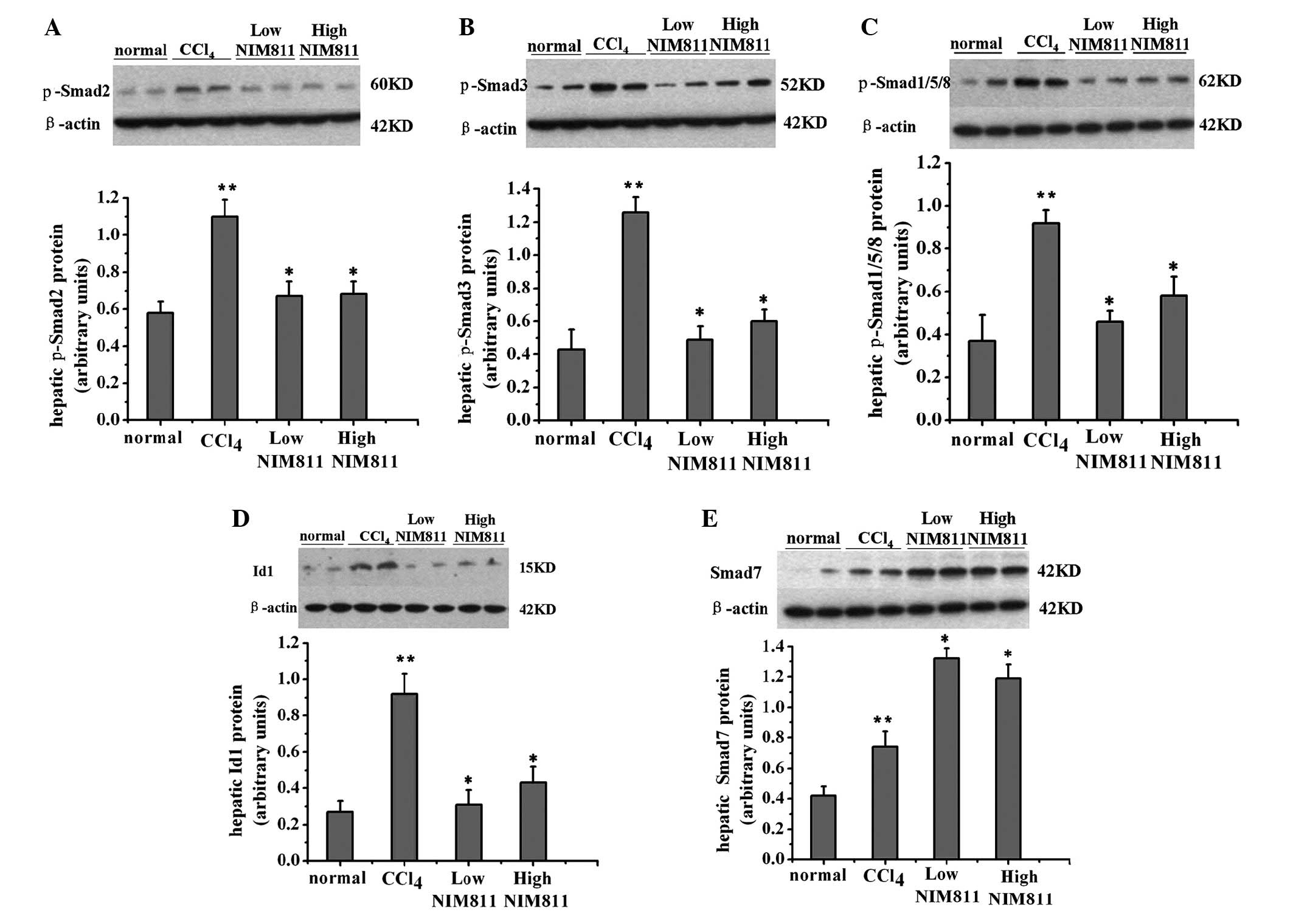

p-Smad2, p-Smad3, Smad7, p-Smad1/5/8 and Id1 were

detected by western blotting. p-Smad2, p-Smad3 and p-Smad1/5/8

protein levels increased following treatment with CCl4,

and decreased in NIM811-treated rats (Fig. 2A–C). The level of Smad7 increased

in rats with liver fibrosis and further increased in NIM811-treated

rats (Fig. 2D). Id1 is the

downstream signaling molecule of the TGF-β/ALK1/Smad1/5/8 pathway

and was decreased following NIM811 treatment (Fig. 2E). Thus, NIM811 downregulated the

TGF-β pathway in CCl4-treated rats.

Effect of NIM811 on collagen I expression

in HSC-T6 cells

To assess the effect of NIM811 on ECM production by

HSCs, collagen I mRNA and protein levels were determined in HSCs

and culture medium. It was demonstrated that the collagen I mRNA

level decreased in the presence of NIM811 compared with normal

control HSC-T6 cells (P<0.05; Table III). This effect was most

pronounced in the presence of NIM811 after 18 h, thus, 18 h was

selected as the time point for the follow-up experiments. Treatment

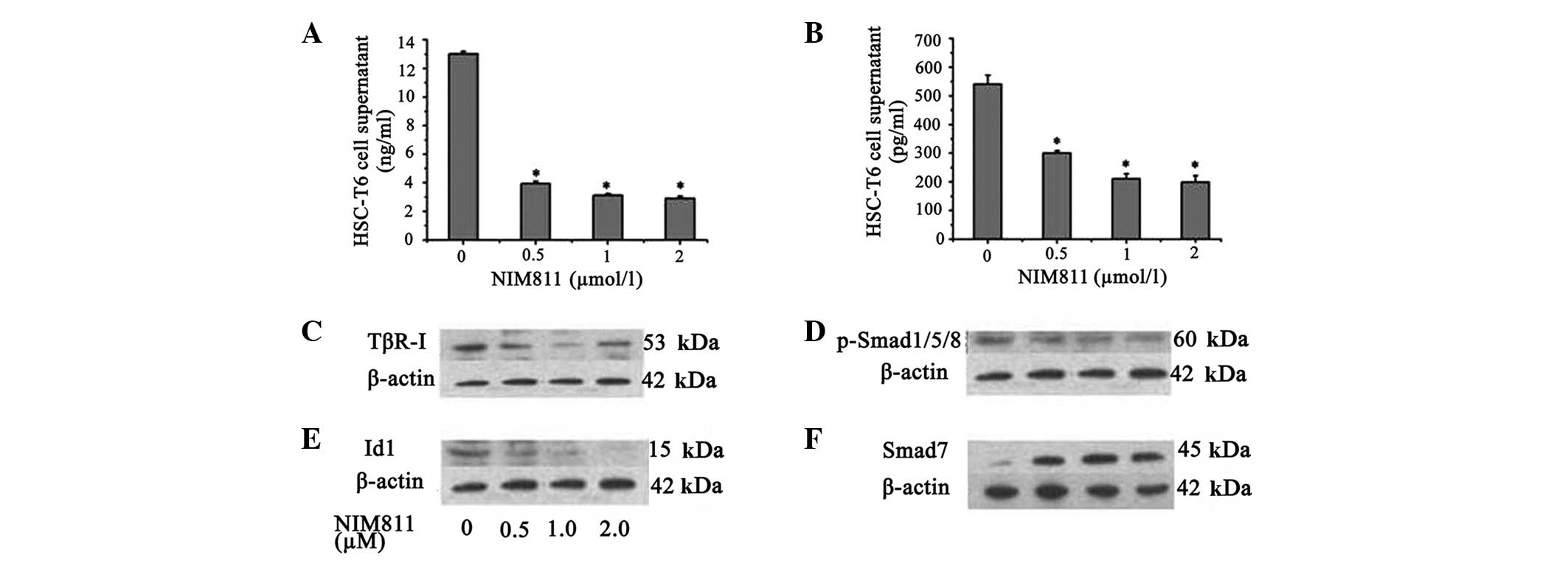

of the cells with increasing concentrations of NIM811 led to a

concentration-dependent suppression of collagen I production; 0.5

µM NIM811 reduced collagen I accumulation by ~70% and 2

µM NIM811 reduced collagen I accumulation by ~77% in HSC-T6

cell supernatant after treatment for 18 h (Fig. 3A).

| Table IIICol I mRNA expression in the HSC-T6

cell line with NIM811 treatment after 6, 12 and 18 h. |

Table III

Col I mRNA expression in the HSC-T6

cell line with NIM811 treatment after 6, 12 and 18 h.

| Col I expression

following NIM811 (µM) treatment

|

|---|

| Incubation time

(h) | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

|---|

| 6 | 1.00±0.05 | 0.95±0.09 | 0.89±0.05a | 0.82±0.05a |

| 12 | 1.00±0.06 | 0.92±0.06a | 0.84±0.07a | 0.76±0.08a |

| 18 | 1.00±0.08 | 0.90±0.04a | 0.75±0.06a | 0.64±0.05a |

Furthermore, the level of collagen I increased after

TGFβ1 treatment and was reduced by NIM811 or TGFβ1 and NIM811

co-treatment (Table IV).

| Table IVmRNA expression in HSC-T6 cells

following treatment with TGF-β1, NIM811 or a combination of the

two. |

Table IV

mRNA expression in HSC-T6 cells

following treatment with TGF-β1, NIM811 or a combination of the

two.

| mRNA | Normal | TGF-β1(5

ng/ml) | NIM811(2

µM) | TGF-β1+NIM811 |

|---|

| Col I | 1.00±0.05 | 1.78±0.08a | 0.64±0.05a | 0.66±0.10a |

| α-SMA | 1.00±0.04 | 2.34±0.15a | 1.46±0.09a | 1.44±0.06a |

| TβR-I | 1.00±0.05 | 1.18±0.09a | 0.56±0.08a | 0.60±0.11a |

| Smad1 | 1.00±0.09 | 1.78±0.13a | 0.68±0.06a | 0.72±0.14a |

| Id1 | 1.00±0.06 | 1.46±0.10a | 0.58±0.05a | 0.62±0.08a |

| Smad7 | 1.00±0.04 | 1.05±0.10 | 1.64±0.14a | 1.48±0.10a |

Effect of NIM811 on TGF-β1 and TβR-I and

TGF-β/ALK1 signaling pathway molecules in cultured HSC-T6

cells

It was demonstrated that NIM811 suppressed the

expression of TGF-β1 and TβR-I mRNA in a concentration-dependent

manner (P<0.05; Table V).

Production of TGF-β1 in HSC-T6 cell supernatant was also decreased

to ~40% by 2 µM NIM811 treatment (P<0.01; Fig. 3B). It was additionally identified

that TβR-I protein expression was suppressed by NIM811 (P<0.05;

Fig. 3C). It was also found that

NIM811 suppressed Smad1 and Id1 transcription, which was

accompanied by decreased phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 and decreased

Id1 protein levels (Table V,

Fig. 3D and E). Smad7, which acts

as an inhibitory Smad, increased following NIM811 treatment

(Table V, Fig. 3F).

| Table VmRNA expression in the HSC-T6 cell

line in the presence of NIM811 for 18 h. |

Table V

mRNA expression in the HSC-T6 cell

line in the presence of NIM811 for 18 h.

| NIM811 (µM)

|

|---|

| mRNA | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

|---|

| TGF-β1 | 1.00±0.06 | 0.91±0.05a | 0.72±0.04a | 0.50±0.07a |

| TβR-I | 1.00±0.08 | 0.58±0.04a | 0.58±0.06a | 0.57±0.05a |

| Smad1 | 1.00±0.09 | 0.84±0.04a | 0.72±0.07a | 0.64±0.06a |

| Id1 | 1.00±0.12 | 0.77±0.04a | 0.58±0.06a | 0.44±0.05a |

| Smad7 | 1.00±0.09 | 1.49±0.10a | 1.57±0.06a | 1.69±0.12a |

To determine whether the addition of exogenous TGF-β

may restore fibrosis in the presence of NIM811, HSC-T6 cells were

stimulated with TGF-β. Results showed that the levels of TβR-I,

Smad1 and Id1 increased following TGFβ1 treatment and were reduced

by treatment with NIM811 alone or TGFβ1 in combination with NIM811

(Table IV).

Discussion

It was demonstrated that NIM811 attenuated collagen

type I expression in the liver of rats with CCl4-induced

liver fibrosis and cultured HSC-T6 cells. This effect may have been

associated with the suppression of TGF-β1 and the TGF-β1 signaling

pathway.

Collagen type I is the predominant constituent of

the ECM in fibrotic liver, and its expression is regulated

transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally by a number of stimuli

and pathways (15,16). TGF-β1 is derived from paracrine and

autocrine sources, and is the key cytokine in the control of tissue

repair. Deregulation of production and degradation of ECM induced

by TGF-β1 is a cause of liver fibrosis (17). TGF-β1 binds to two different

serine/threonine kinase receptors, TβR-I and TβR-II (18). Upon ligand binding, TβR-I

specifically activates intracellular Smad proteins (19,20),

which are a family of bifunctional molecules that are known TGF-β1

downstream signals. Following Smad activation, numerous

extracellular and intracellular signals converge to fine-tune and

enhance the effects of TGF-β1 during fibrogenesis (1,21,22).

Smad1, 2 and 3 are stimulatory, whereas Smad7 is inhibitory and is

antagonized by Id1 (23,24). Therefore, the TGF-β1 signaling

pathway, including TGF-β/ALK5 and TGF-β/ALK1 branches, has an

important role in liver fibrogenesis.

TGF-β1 signal cascades through Smad2 and Smad3

strongly regulate the expression of the type I collagen gene

(20,25). In the present study, decreased

liver collagen type I mRNA expression was accompanied by

downregulation of phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 in rats with

liver fibrosis treated with NIM811. NIM811 also suppressed p-Smad2

and p-Smad3 in HSCs in a previous study, which indicates that

NIM811 decreases collagen accumulation through downregulation of

TGF-β1/ALK5/Smad2/3 branch (11).

It was also demonstrated that NIM811 inhibited the

protein levels of phospho-Smad1/5/8 and Id1 in the liver of

NIM811-treated rats. Recent research has demonstrated that the

TGF-β1/ALK1/Smad1 pathway and its downstream factor Id1 are

important in liver fibrosis. Id1 is the helix-loop-helix (HLH)

protein inhibitor of differentiation 1, and is hypothesized to

affect the balance between cell growth and differentiation by

negatively regulating the function of basic HLH transcription

factors (26). Recently, Id1 has

been found to be a novel TGF-β1 target gene in HSCs. Id1 expression

and Smad1 phosphorylation are co-induced during hepatic

fibrogenesis. The existence of ALK1 and the TGF-β1/ALK1/Smad1

pathway is crucial during the transdifferentiation of primary rat

HSCs to myofibroblasts (23).

Activation of the TGF-β1/ALK1/Smad1 pathway may be enhanced by

TGFβ1 in LX-2 cells (27).

Treatment of HSCs with TGF-β1 led to increased Id1 protein

expression, which was not directly mediated by the ALK5/Smad2/3,

but by the ALK1/Smad1 pathway (27).

The two branches of the TGF-β1 signaling pathway,

TGF-β1/ALK1/Smad1 and TGF-β1/ALK5/Smad2, are not isolated, they act

together to provide feedback via Id1. It has been proposed that

R-Smads exert their signal transduction effect through protein

phosphorylation. Smad7 acts as a general inhibitor of the TGF-β

family, and inhibits TGF-β1 signaling by preventing activation of

R- and Co-Smads (19,28,29).

Moreover, ectopic Id1 overexpression is sufficient to overcome the

inhibitory effects of Smad7 on HSC activation and α-SMA fiber

formation in vitro (23),

which leads to aggravation of liver fibrosis.

HSCs are perisinusoidal cells in the subendothelial

space between hepatocytes and sinusoidal endothelial cells, and are

key in collagen accumulation (30). They can be identified by their

vitamin A autofluorescence, perisinusoidal orientation, and

expression of the cytoskeletal proteins desmin and α-SMA. The

present study showed that NIM811 suppressed α-SMA protein

expression in the adjacent sinusoids in CCl4-treated

rats, which indicated that NIM811 decreased the extent of HSC

activation in vivo, and that HSCs are one of the targets of

NIM811. Therefore, HSCs were selected to conduct an in vitro

study to confirm these in vivo results, which demonstrated

that NIM811 inhibited TGF-β1 and its downstream signaling

molecules.

The results suggest another possible antifibrotic

mechanism of NIM811, which inhibits the transcription of Smad1 and

Id1, accompanied by a decrease in phospho-Smad1/5/8 and Id1 protein

expression. NIM811 can attenuate the fibrogenic signaling of HSCs

by upregulating Smad7 expression. The results also showed that the

TGFβ1/ALK1/Smad1 pathway may represent a potential target for

antifibrotic therapy. However, which components in the compound

exhibit the inhibitory effects requires further investigation.

Fibrosis is caused by increased matrix production by

HSCs and an increase in HSC numbers. It has been shown that NIM811

suppressed HSC proliferation, but not apoptosis in vitro

(7). Platelet-derived growth

factor (PDGF) is the most potent stellate cell mitogen identified

thus far (31,32). Downstream pathways of PDGF

signaling have been carefully characterized in stellate cells, and

induction of PDGF receptors early in stellate cell activation

increases responsiveness to this potent mitogen (33–36).

Therefore, our next study will investigate the effect of NIM811 on

cultured HSCs isolated from CCl4-induced rats and the

PDGF signaling pathway.

In conclusion, the results further implicate the

involvement of the TGFβ1/ALK1/Smad1 and TGF-β1/ALK5/Smad2 pathways

during the development of hepatic fibrosis, and suggest that NIM811

may emerge as a novel option for hepatic fibrosis therapy through

downregulation of the TGF-β1 pathway.

Abbreviations:

|

TGF-β

|

transforming growth factor-β

|

|

HSC

|

hepatic stellate cell

|

|

SMA

|

α-smooth muscle actin

|

References

|

1

|

Friedman SL: Mechanisms of hepatic

fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 134:1655–1669. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Moreno M and Bataller R: Cytokines and

reninangiotensin system signaling in hepatic fibrosis. Clin Liver

Dis. 12:825–852. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gressner OA, Lahme B, Demirci I, Gressner

AM and Weiskirchen R: Differential effects of TGF-beta on

connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) expression in hepatic

stellate cells and hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 47:699–710. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wynn TA: Cellular and molecular mechanisms

of fibrosis. J Pathol. 214:199–210. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Parsons CJ, Takashima M and Rippe RA:

Molecular mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 22(Suppl 1): S79–S84. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Casini A, Pinzani M, Milani S, Grappone C,

Galli G, Jezequel AM, Schuppan D, Rotella CM and Surrenti C:

Regulation of extracellular matrix synthesis by transforming growth

factor beta 1 in human fat-storing cells. Gastroenterology.

105:245–253. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kohjima M, Enjoji M, Higuchi N, Kotoh K,

Kato M, Takayanagi R and Nakamuta M: NIM811, a nonimmunosuppressive

cyclosporine analogue, suppresses collagen production and enhances

collagenase activity in hepatic stellate cells. Liver Int.

27:1273–1281. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Waldmeier PC, Feldtrauer JJ, Qian T and

Lemasters JJ: Inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability

transition by the nonimmunosuppressive cyclosporin derivative

NIM811. Mol Pharmacol. 62:22–29. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Pediaditakis P,

Ramshesh VK, Currin RT, Tikunov A, Holmuhamedov E and Lemasters J:

Minocycline and N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporin (NIM811) mitigate

storage/reperfusion injury after rat liver transplantation through

suppression of the mitochondrial permeability transition.

Hepatology. 47:236–246. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhong Z, Theruvath TP, Currin RT,

Waldmeier PC and Lemasters JJ: NIM811, a mitochondrial permeability

transition inhibitor, prevents mitochondrial depolarization in

small-for-size rat liver grafts. Am J Transplant. 7:1103–1111.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kohjima M, Enjoji M, Higuchi N, Kotoh K,

Kato M, Takayanagi R and Nakamuta M: NIM811, a nonimmunosuppressive

cyclosporine analogue, suppresses collagen production and enhances

collagenase activity in hepatic stellate cells. Liver Int.

27:1273–1281. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang H, Zhang Y, Wang T, You H and Jia J:

N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporine attenuates CCl-induced liver

fibrosis in rats by interacting with cyclophilin B and D. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 26:558–567. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang H, Zhang Y, Wang T, You H and Jia J:

N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporine attenuates CCl-induced liver

fibrosis in rats by interacting with cyclophilin B and D. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 26:558–567. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dooley S, Delvoux B, Lahme B,

Mangasser-Stephan K and Gressner AM: Modulation of transforming

growth factor beta response and signaling during

transdifferentiation of rat hepatic stellate cells to

myofibroblasts. Hepatology. 31:1094–1106. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Friedman SL: Hepatic fibrosis-overview.

Toxicology. 254:120–129. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Breitkopf K, Godoy P, Ciuclan L, Singer MV

and Dooley S: TGF-beta/Smad signaling in the injured liver. Z

Gastroenterol. 44:57–66. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Border WA and Noble NA: Transforming

growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 331:1286–1292.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kolodziejczyk SM and Hall BK: Signal

transduction and TGF-beta superfamily receptors. Biochem Cell Biol.

74:299–314. 1996. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Miyazawa K, Shinozaki M, Hara T, Furuya T

and Miyazono K: Two major Smad pathways in TGF-beta superfamily

signalling. Genes Cells. 7:1191–1204. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Attisano L and Wrana JL: Signal

transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 296:1646–1647.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Higashiyama R, Inagaki Y, Hong YY, Kushida

M, Nakao S, Niioka M, Watanabe T, Okano H, Matsuzaki Y, Shiota G

and Okazaki I: Bone marrow-derived cells express matrix

metalloproteinases and contribute to regression of liver fibrosis

in mice. Hepatology. 45:213–222. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Inagaki Y and Okazaki I: Emerging insights

into transforming growth factor beta Smad signal in hepatic

fibrogenesis. Gut. 56:284–292. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wiercinska E, Wickert L, Denecke B, Said

HM, Hamzavi J, Gressner AM, Thorikay M, ten Dijke P, Mertens PR,

Breitkopf Ka and Dooley S: Id1 is a critical mediator in

TGF-beta-induced transdifferentiation of rat hepatic stellate

cells. Hepatology. 43:1032–1041. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Miyazono K, Kusanagi K and Inoue H:

Divergence and convergence of TGF-beta/BMP signaling. J Cell

Physiol. 187:265–276. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Friedman SL, Yamasaki G and Wong L:

Modulation of transforming growth factor beta receptors of rat

lipocytes during the hepatic wound healing response. Enhanced

binding and reduced gene expression accompany cellular activation

in culture and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 269:10551–10558.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zebedee Z and Hara E: Id proteins in cell

cycle control and cellular senescence. Oncogene. 20:8317–8325.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Li L, Zhao XY and Wang BE: Down-regulation

of transforming growth factor beta 1/activin receptor-like kinase 1

pathway gene expression by herbal compound 861 is related to

deactivation of LX-2 cells. World J Gastroenterol. 14:2894–2899.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Itoh S, Itoh F, Goumans MJ and Ten Dijke

P: Signaling of transforming growth factor-beta family members

through Smad proteins. Eur J Biochem. 267:6954–6967. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Itóh S, Landström M, Hermansson A, Itoh F,

Heldin CH, Heldin NE and ten Dijke P: Transforming growth factor

beta1 induces nuclear export of inhibitory Smad7. J Biol Chem.

273:29195–29201. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Friedman SL: Hepatic stellate cells:

Protean, multifunctional and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol

Rev. 88:125–172. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pinzani M: PDGF and signal transduction in

hepatic stellate cells. Front Biosci. 7:d1720–d1726. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Borkham-Kamphorst E, van Roeyen CR,

Ostendorf T, Floege J, Gressner AM and Weiskirchen R:

Pro-fibrogenic potential of PDGF-D in liver fibrosis. J Hepatol.

46:1064–1074. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pinzani M and Marra F: Cytokine receptors

and signaling in hepatic stellate cells. Semin Liver Dis.

21:397–416. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lechuga CG, Hernandez-Nazara ZH, Hernández

E, Bustamante M, Desierto G, Cotty A, Dharker N, Choe M and Rojkind

M: PI3K is involved in PDGF-beta receptor upregulation post-PDGF-BB

treatment in mouse HSC. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

291:G1051–G1061. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Harder KW, Owen P, Wong LK, Aebersold R,

Clark-Lewis I and Jirik FR: Characterization and kinetic analysis

of the intracellular domain of human protein tyrosine phosphatase

beta (HPTP beta) using synthetic phosphopeptides. Biochem J.

298:395–401. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wong L, Yamasaki G, Johnson RJ and

Friedman SL: Induction of beta-platelet-derived growth factor

receptor in rat hepatic lipocytes during cellular activation in

vivo and in culture. J Clin Invest. 94:1563–1569. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|