Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the most common birth

defects. According to the World Health Organization, 360,000,000

individuals worldwide have disabling hearing loss (www.who.int/), including 328,000,000 adults and

32,000,000 children. Deafness is a multi-factorial disease,

predominantly induced by genetic or environmental causes or their

interactions (1). It is suggested

that ~50% of deafness is hereditary, which includes syndromic

hearing loss and nonsyndromic hearing loss (NSHL), which comprises

~70% of cases of hereditary deafness (2). Of NSHL, almost 80% of cases is due to

autosomal recessive inheritance, and it has been demonstrated that

autosomal recessive NSHL is associated with >50 genes (3) (http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/), including the gap

junction protein β 2 (GJB2), solute carrier family 26, member 4

(SLC26A4) and mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA genes. In NSHL, ~50% of

deafness is caused by mutation of the GJB2 gene (4,5), and

in the GJB2 gene, >90 mutations have been identified. GJB2

35delC is the most common mutation in the European population

(6), while 235delC is common in

the Asian population (7). Mutation

of the SLC26A4 gene is the second leading cause of NSHL, which

contains 21 exons and has been identified to contain ~200

mutations, with IVS7-2A>G and 2168A>G being the two most

common mutations in Asian population (8–10).

The 1,555A>G mutation in the mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA gene was

the first identified genetic cause for aminoglycoside-induced NSHL

(11). Previous molecular

etiological studies have shown that GJB2, SLC26A4 and 12S rRNA are

three common deafness-associated genes in NSHL among the Chinese

population (12–15). Therefore, mutational screening in

these three genes may be effective and beneficial for diagnosing

deafness in this population.

It is common for deaf couples to have children

together; certain couples may have the same disease-causing genetic

mutation. Thus, confirmation of the pathogenic genotype of deaf

patients may assist in determining the genotype of their children.

In families with children affected by NSHL, it is important to

confirm the genotypes of the couples and their deaf children, in

order to determine the risk in their next pregnancy. In the present

study, the GJB2 gene, SLC26A4 gene and 12S rRNA were examined by

Sanger sequencing in 117 deaf patients, including 39 deaf couples

and 39 deaf individuals. Furthermore, seven pregnant women were

offered prenatal diagnosis via amniocentesis at 18–21 weeks

gestation. The aim of the present study was to analyze the genetics

of deafness and provide appropriate genetic counseling about

hearing loss to our patients.

Materials and methods

Subjects

In the present study 117 deaf patients, aged between

3 months and 35 years were recruited. These patients were diagnosed

with nonsyndromic neurosensory deafness at Nanjing Maternity and

Child Health Care Hospital (Nanjing, China) between 2009 and 2013,

with hearing loss of >70 dB. Any patients with systemic disease,

dysgnosia, syndromic deafness or a history of meningitis, otitis

media or trauma of the ear were excluded from the investigations.

The present study was performed in accordance with the declaration

of Helsinki, and was performed following approval from the ethics

committee of Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital

(Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China). Written informed

consent was obtained from the patient.

DNA extraction

To obtain DNA, 2 ml peripheral blood was collected

and then placed into tubes with ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid

(EDTA; Greiner Bio-One International GmbH). For the pregnant women

offered prenatal diagnosis, 10 ml amniotic fluid was collected at

18–21 weeks gestation, and DNA was extracted using a DNA extraction

kit (Xiamen Zhishan Biological Company, Xiamen, China), according

to manufacturer's protocol, followed by storage at −20°C.

Primer design

Primers were designed, according to those previously

described (13–15), which were used to perform

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing. The

primer sequences are listed in Table

I, and were synthesized by Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The coding sequences of GJB2

were amplified, following which GJB2 genetic mutations were

detected by Sanger sequencing (13,16,17).

Furthermore, mitochondrial DNA from 1,428 to 1,890 were also

amplified and 1,555A>G mutation of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA

gene were detected (15,18,19).

The hot-spot regions of the SLC26A4 gene, including exons 5, 7, 8,

10, 17 and 19, were also amplified, of which exons 7 and 8 were

amplified in one amplicon. Therefore, five fragments were amplified

to cover the six exons and flanking sequence, following which the

SLC26A4 gene mutation was detected. For patients with one allelic

variant in the hot-spot regions, the other exons were sequenced one

by one, until two mutant alleles were identified, as previously

described (14,20,21).

| Table IPCR primers for the GJB2 gene, SLC26A4

gene and mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA. |

Table I

PCR primers for the GJB2 gene, SLC26A4

gene and mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA.

| Gene | Exon | PCR primer

(5′–3′) | Product length

(bp) |

|---|

| GJB2 | 2 |

F-TTGGTGTTTGCTCAGGAAGA | 872 |

| |

R-GGTTGCCTCATCCCTCTCAT | |

| SLC26A4 | 5 |

F-CCTATGCAGACACATTGAACATTTG | 442 |

| |

R-TGAGCCTTAATAAGTGGGGTCTTG | |

| 7+8 |

F-CATGGTTTTTCATGTGGGAAGATTC | 502 |

| |

R-AGACTGACTTACTGACTTAATGT | |

| 10 |

F-AAATACTCAGCGAAGGTCTTGC | 250 |

| |

R-CGAGCCTTCCTCTGTTGC | |

| 17 |

F-CCAAGGAACAGTGTGTAGGTC | 423 |

| |

R-CCCATGTATTTGCCCTGTTGC | |

| 19 |

F-TCACTTGAACTTGGGACGCGGA | 383 |

| |

R-CAACAGCTAGACTAGACTTGTG | |

| Mitochondrial 1

allelic | 1,555 |

F-GCAGTAAACTAAGAGTAGAGT | 463 |

| DNA 12S rRNA | |

R-GGCTCTCCTTGCAAAGTTAT | |

PCR amplification

The GoTaq® PCR system was purchased from

Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA). The total volume of the PCR

reaction mixture was 50 µl, including 10 µl of 5X

Green GoTaq® Reaction Buffer, 2 µl of 10 mmol/l

dNTP, 1 µl of each (10 µmol/l) primer, 0.25 µl

of 5 U/µl GoTaq® DNA polymerase, 5 µl of

the 20 ng/µl DNA template and 30.75 µl distilled

water. The amplification reaction conditions for exons 7 and 8 of

the SLC26A4 gene were as follows: 95°C for 5 min; followed by 35

cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec, and

a final step of 72°C for 7 min. For the remaining six exons, the

reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min; followed by 35

cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min, and

a final step of 72°C for 7 min. The amplified products were stored

at 4°C.

Sequence analysis

Following PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis was

performed, and the products were purified according to TIANgel Midi

DNA Purification kits (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China),

following which the purified products were sequenced. Sequencing

kits were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA).

The reaction system contained 1 µl Bigdye, 3 µl

buffer, 2 µl primers and 5 µl purified products in a

total volume of 20 µl. The reaction conditions were as

follows: 95°C for 1 min; followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec,

50°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 4 min. The amplified products were

stored at 4°C. The sequences of the primers are listed in Table I. In addition, the sequencing

products were purified with 100 mM EDTA solution and alcohol

solution. Following purification, the products were dried and were

dissolved in 100% HiDi Formamide (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Subsequently, all products were sequenced (forward and

reverse) using an ABI3130 analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The sequence results were aligned with

standard sequences using SeqBuilder procedures on Lasergene

software, version 7.1 (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI, USA). The GJB2,

SLC26A4 and mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA genetic standards were

NM_004004 [GenBank, National Center for Biotechnology Information

(NCBI), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_004004],

ENSG00000091137 (Ensembl, European Bioinformatics Institute,

www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Gene/Sequence?g=ENSG00000091137)

and the Cambridge reference sequence, NC_001807 (GenBank, NCBI,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_001807.4),

respectively.

Results

Genetic sequencing of 117 deaf

patients

In the present study, genetic detection was

performed in 117 deaf patients, of which 36 cases were confirmed to

carry two pathogenic mutations. The positive rate was 30.77%

(Table II), including 19 cases

with GJB2 gene mutations (16.24%), 12 cases with SLC26A4 gene

mutations (10.26%) and five cases with the 1,555A>G allelic

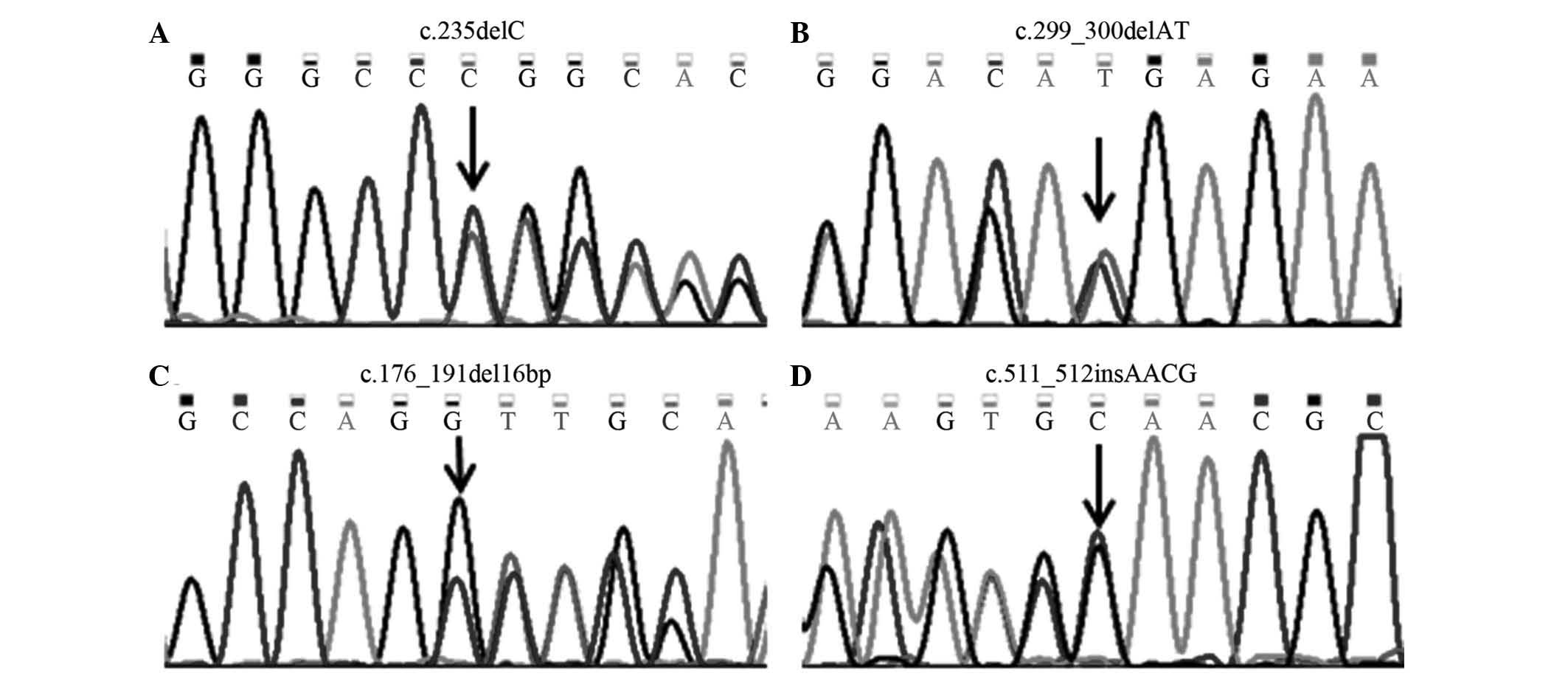

mutation of mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA (4.27%). In total, four GJB2

gene mutations (Fig. 1), and eight

SLC26A4 gene mutations (Fig. 2)

were identified.

| Table IIMutant alleles of deafness-associated

genes in 36 deaf patients. |

Table II

Mutant alleles of deafness-associated

genes in 36 deaf patients.

| Gene | Mutant allele | Patients (n) | Total (n) | Rate (%) |

|---|

| GJB2 | 235delC/235delC | 9 | 19 | 16.24 |

|

235delC/299_300delAT | 5 | | |

|

235delC/176_191del16bp | 2 | | |

|

299_300delAT/299_300delAT | 1 | | |

|

176_191del16bp/176_191del16bp | 1 | | |

|

235delC/511_512insAACG | 1 | | |

| SLC26A4 |

IVS7-2A>G/IVS7-2A>G | 4 | 12 | 10.26 |

| IVS7-2A>G/1226

G>A | 1 | | |

|

IVS7-2A>G/1174A>T | 1 | | |

|

IVS7-2A>G/2027T>A | 1 | | |

| IVS7-2A>G/2168

A>G | 1 | | |

|

589G>A/589G>A | 1 | | |

| 1174A>T/1975

G>C | 1 | | |

|

1226G>A/1226G>A | 1 | | |

|

1079C>T/2168A>G | 1 | | |

| Mitochondrial

DNA | 1555A>G | 5 | 5 | 4.27 |

| 12S rRNA | | | | |

| Total | | | 36 | 30.77 |

Genetic sequencing of 39 deaf

couples

The 117 deaf patients recruited in the present study

included 39 pairs of deaf couples, of which four couples were

confirmed to have two deafness-causing mutations (10.26%). Among

these, deafness in one couple was caused by SLC26A4 gene mutations,

whose children will be deaf. In one deaf couple, deafness was

caused by GJB2 and SLC26A4 gene mutations, respectively. The

present study hypothesized that their children will have a low risk

of deafness with no need for prenatal diagnosis as the parents

pathogenic mutations are in different genes, the child will be

heterozygous for these two genes which are associated with

autosomal recessive hearing loss. Furthermore, in one couple, the

husband had two GJB2 gene mutations, whereas the wife had

1,555A>G mutation of mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA. Their children

would carry a GJB2 gene heterozygous mutation and mitochondrial DNA

mutation, and may be advised to avoid taking aminoglycoside

antibiotics as the mutation 1,555A>G is important in

aminoglycoside-induced nonsyndromic deafness (18). In addition, the husband of one

couple had 1,555A>G mutation of mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA,

whereas the wife carried two GJB2 gene mutation. The present study

hypothesized that their children would be at low risk of deafness

due to their child carrying a heterozygous GJB2 gene mutation. The

results of genetic sequencing indicated that, in 11 couples, only

one of each couple (28.21%) was confirmed to have deafness-causing

mutations, which indicated that their offspring were at low risk of

deafness. Table III shows the

results of genetic analyses.

| Table IIIGenetic sequencing of 15 couples. |

Table III

Genetic sequencing of 15 couples.

| Couple | Gender/age

(years) | GJB2 mutation | SLC26A4

mutation | 12S rRNA

mutation |

|---|

| 1 | Female/20 |

299_300delAT/299_300delAT | – | – |

| Male/28 | – | – | – | |

| 2 | Female/29 |

235delC/511_512insAACG | – | – |

| Male/30 | – | – | – | |

| 3 | Female/22 | – | – | – | |

| Male/29 | | – | – | 1555A>G |

| 4 | Female/28 | | – | – | 1555A>G |

| Male/29 |

235delC/235delC | – | – |

| 5 | Female/24 | | – |

1226G>A/1226G>A | – |

| Male/25 | | – |

IVS7-2A>G/2027T>A | – |

| 6 | Female/24 | | – | – | 1555A>G |

| Male/24 | – | – | – | |

| 7 | Female/28 |

235delC/235delC | – | – |

| Male/28 | – | – | – | |

| 8 | Female/23 |

235delC/235delC | – | – |

| Male/24 | | – | – | – |

| 9 | Female/26 | | – | – | – |

| Male/27 | | – | IVS7-2A>G/1226

G>A | – |

| 10 | Female/28 | | – | – | – |

| Male/30 | | – | | 1555A>G |

| 11 | Female/25 | |

235delC/176_191del16bp | – | – |

| Male/25 | | – | – | – |

| 12 | Female/25 | |

235delC/235delC | – | – |

| Male/26 | | – | – | – |

| 13 | Female/26 | | – | – | |

| Male/31 | | – |

589G>A/589G>A | – |

| 14 | Female/28 | |

235delC/299_300delAT | – | – |

| Male/29 | | – |

IVS7-2A>G/IVS7-2A>G | – |

| 15 | Female/29 | |

235delC/176_191del16bp | – | – |

| Male/34 | | – | – | 1555A>G |

Genetic sequencing of families with deaf

children and prenatal diagnosis

In the 39 deaf patients, 17 cases were identified

with GJB2 gene or SLC26A4 gene mutations. Subsequently, their

parents received genetic analysis to confirm whether they were

carriers (Table IV). In 7/17

families, prenatal diagnosis was performed during their next

pregnancy. The results showed that two fetuses had the same

genotype as the proband. These two families decided to terminate

the pregnancy. No mutations were identified in one fetus, and the

genotypes of the other four fetuses were the same as one parent.

The result of clinical follow-up demonstrated that they had normal

hearing following birth.

| Table IVGenetic sequencing of 17 couples with

deaf children. |

Table IV

Genetic sequencing of 17 couples with

deaf children.

| Couple | Mutation

| Follow-up |

|---|

| Child

(proband) | Father | Mother | Fetus |

|---|

| 1a |

235delC/299_300delAT | 299_300delAT | 235delC |

235delC/299_300delAT | Ending

pregnancy |

| 2a |

235delC/299_300delAT | 235delC | 299_300delAT |

299_300delAT/WT | Normal hearing |

| 3a |

235delC/235delC | 235delC | 235delC | 235delC/WT | Normal hearing |

| 4a |

176_191del16bp/176_191del16bp | 176_191del16bp | 176_191del16bp |

176_191del16bp/WT | Normal hearing |

| 5b |

IVS7-2A>G/IVS7-2A>G | IVS7-2A>G | IVS7-2A>G | WT/WT | Normal hearing |

| 6b |

IVS7-2A>G/IVS7-2A>G | IVS7-2A>G | IVS7-2A>G |

IVS7-2A>G/IVS7-2A>G | Ending

pregnancy |

| 7b |

IVS7-2A>G/2168A>G | IVS7-2A>G | 2168A>G |

IVS7-2A>G/WT | Normal hearing |

| 8a |

235delC/299_300delAT | 299_300delAT | 235delC | | |

| 9a |

235delC/299_300delAT | 299_300delAT | 235delC | | |

| 10a |

235delC/235delC | 235delC | 235delC | | |

| 11a |

235delC/235delC | 235delC | 235delC | | |

| 12a |

235delC/235delC | 235delC | 235delC | | |

| 13a |

235delC/235delC | 235delC | 235delC | | |

| 14b |

IVS7-2A>G/1174A>T | 1174A>T | IVS7-2A>G | | |

| 15b |

IVS7-2A>G/IVS7-2A>G | IVS7-2A>G | IVS7-2A>G | | |

| 16b |

1174A>T/1975G>C | 1174A>T | 1975G>C | | |

| 17b |

1079C>T/2168A>G | 2168A>G | 1079C>T | | |

Discussion

The provision of appropriate genetic counseling for

patients with hearing loss remains a challenge in clinical

practice. Deafness exhibits marked genetic heterogeneity and

phenotypic variability (1,2). At present, hundreds of genes have

been identified to cause hereditary hearing loss, including the

GJB2 gene, SLC26A4 gene and the mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA

1,555A>G mutation, which have been confirmed to be closely

associated with NSHL (1,16–23).

The present study used Sanger sequencing to analyze

mutations of GJB2, SLC26A4 and the mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA

1,555A>G in 117 patients with NSHL. The results revealed that 36

of the 117 patients (30.77%) carried two deafness-causing

mutations, including the GJB2 gene mutations (16.24%), SLC26A4 gene

mutations (10.26%) and mitochondrial DNA 12SrRNA 1555 locus

mutation (4.27%). The 235delC mutation in the GJB2 gene mutation

has been identified at the highest rate in patients in the present

study and is also the most common in the Asian population (24). The present study identified the

mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA 1,555A>G locus mutation in ~4.27% of

the patients, which follows the pattern of maternal inheritance

(11,18). It may be the situation that there

are healthy individuals with normal hearing carrying the

1,555A>G mutation. Thus, once this mutation is identified, the

family members can avoid the use of aminoglycoside antibiotics,

preventing drug-induced deafness (25). The SLC26A4 gene contains 21 exons.

The present study selected certain hot-spot regions, SLC26A4 exons

5, 7, 8, 10, 17 and 19, for sequencing. The IVS7-2A>G mutation

is the most common mutation in the SLC26A4 gene (10). For patients with one allelic

variant in the hot-spot regions, the remaining exons were sequenced

one by one until two mutant alleles had been identified. The

results found the second mutant allele, the missense mutation

1079C>T, in exon 9 of one patient. In addition, 11 patients

carrying SLC26A4 mutations were detected using hot-spot region

screening, whereas only one case was identified by complete exon

sequencing. According to the SLC26A4 gene mutation spectrum, the

Sanger sequencing method detecting hot-spot regions of the SLC26A4

gene has been found to have clinical value in identifying mutations

associated with deafness (14).

In the present study, there were 39 deaf couples.

Traditionally, it is thought that there is a high possibility of

deaf couples having hearing-impaired offspring, however, the

majority of couples with hearing impairment have deafness induced

by environmental causes or due to different pathogenic genes, thus,

the risk of their children being deaf is low (12). Additionally, in couples with

deafness due to GJB2 and SLC26A4 gene mutation, their children were

predicted to be carriers with normal hearing. In one couple, in

which the mother had hearing loss caused by the mitochondrial DNA,

12S rRNA mutation, their children were predicted to be a carrier

with normal hearing, in the absence of use with ototoxic drugs.

However, they cannot be a carrier of the mutational gene if the

father has hearing loss caused by the mitochondrial DNA 12S rRNA

mutation, the children would be predicted to have normal hearing.

Therefore, genetic analysis of deafness-associated genes can reduce

anxiety in deaf couples, and determine the risk in their next

pregnancy.

In the present study, 3 deafness-associated genes in

39 deaf patients and their parents were sequenced, and the results

revealed 17 cases carried two confirmed pathogenic mutations, whose

parents were both carriers of the same genetic mutation. In

addition, seven pregnant women were offered prenatal diagnosis. The

genetic analysis revealed that the genotypes of two fetuses were

the same as the probands. Of the remaining fetuses, four were

carriers, and one was identified without mutations in the genes

analyzed.

In conclusion, the gene sequencing performed in the

present study was convenient and reliable for the genetic testing

of NSHL. In addition, the method could be applied in clinical

laboratories due to its simple process and low cost, providing

easier genetic assessment. In addition, results from the present

study provided accurate information for genetic counseling and

prenatal diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the Program for

Leading Talents and Medical Innovative Team of Jiangsu Province

(grant no. LJ201109), the Special Funds of Clinical Medicine

Science and Technology of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BL2012039),

the Science and Technology Research and Development Program of

Health Bureau of Nanjing City (grant no. YKK11059) and the Training

Program for Young Talents of Nanjing City.

References

|

1

|

Shearer AE and Smith RJ: Genetics:

Advances in genetic testing for deafness. Curr Opin Pediatr.

24:679–686. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cryns K and Van Camp G: Deafness genes and

their diagnostic applications. Audiol Neurootol. 9:2–22. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hoefsloot LH, Feenstra I, Kunst HP and

Kremer H: Genotype phenotype correlations for hearing impairment:

Approaches to management. Clin Genet. 85:514–523. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rabionet R, Gasparini P and Estivill X:

Molecular genetics of hearing impairment due to mutations in gap

junction genes encoding beta connexins. Hum Mutat. 16:190–202.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kenneson A, Van Naarden Braun K and Boyle

C: GJB2 (connexin 26) variants and nonsyndromic sensorineural

hearing loss: A HuGE review. Genet Med. 4:258–274. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Snoeckx RL, Huygen PL, Feldmann D, Marlin

S, Denoyelle F, Waligora J, Mueller-Malesinska M, Pollak A, Ploski

R, Murgia A, et al: GJB2 mutations and degree of hearing loss: A

multicenter study. Am J Hum Genet. 77:945–957. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ohtsuka A, Yuge I, Kimura S, Namba A, Abe

S, Van Laer L, Van Camp G and Usami S: GJB2 deafness gene shows a

specific spectrum of mutations in Japan, including a frequent

founder mutation. Hum Genet. 112:329–333. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hilgert N, Smith RJ and Van Camp G:

Forty-six genes causing nonsyndromic hearing impairment: Which ones

should be analyzed in DNA diagnostics? Mutat Res. 681:189–196.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang QJ, Zhao YL, Rao SQ, Guo YF, Yuan H,

Zong L, Guan J, Xu BC, Wang DY, Han MK, et al: A distinct spectrum

of SLC26A4 mutations in patients with enlarged vestibular aqueduct

in China. Clin Genet. 72:245–254. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Du W, Guo Y, Wang C, Wang Y and Liu X: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of common mutations of SLC26A4

gene in Asian populations. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.

77:1670–1676. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kokotas H, Petersen MB and Willems PJ:

Mitochondrial deafness. Clin Genet. 71:379–391. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yuan Y, You Y, Huang D, Cui J, Wang Y,

Wang Q, Yu F, Kang D, Yuan H, Han D and Dai P: Comprehensive

molecular etiology analysis of nonsyndromic hearing impairment from

typical areas in China. J Transl Med. 7:792009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Dai P, Yu F, Han B, Liu X, Wang G, Li Q,

Yuan Y, Liu X, Huang D, Kang D, et al: GJB2 mutation spectrum in

2,063 Chinese patients with nonsyndromic hearing impairment. J

Transl Med. 7:262009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yuan Y, Guo W, Tang J, Zhang G, Wang G,

Han M, Zhang X, Yang S, He DZ and Dai P: Molecular epidemiology and

functional assessment of novel allelic variants of SLC26A4 in

non-syndromic hearing loss patients with enlarged vestibular

aqueduct in China. PLoS One. 7:e499842012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li Z, Li R, Chen J, Liao Z, Zhu Y, Qian Y,

Xiong S, Heman-Ackah S, Wu J, Choo DI and Guan MX: Mutational

analysis of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in Chinese pediatric

subjects with aminoglycoside-induced and non-syndromic hearing

loss. Hum Genet. 117:9–15. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Estivill X, Fortina P, Surrey S, Rabionet

R, Melchionda S, D'Agruma L, Mansfield E, Rappaport E, Govea N,

Milà M, et al: Connexin-26 mutations in sporadic and inherited

sensorineural deafness. Lancet. 351:394–398. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Morell RJ, Kim HJ, Hood LJ, Goforth L,

Friderici K, Fisher R, Van Camp G, Berlin CI, Oddoux C, Ostrer H,

et al: Mutations in the connexin 26 gene (GJB2) among Ashkenazi

Jews with nonsyndromic recessive deafness. N Engl J Med.

339:1500–1505. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Prezant TR, Agapian JV, Bohlman MC, Bu X,

Oztas S, Qiu WQ, Arnos KS, Cortopassi GA, Jaber L and Rotter JI:

Mitochondrial ribosomal RNA mutation associated with both

antibiotic-induced and non-syndromic deafness. Nat Genet.

4:289–294. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao H, Li R, Wang Q, Yan Q, Deng JH, Han

D, Bai Y, Young WY and Guan MX: Maternally inherited

aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic deafness is associated with

the novel C1494T mutation in the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in a

large Chinese family. Am J Hum Genet. 74:139–152. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Pryor SP, Madeo AC, Reynolds JC, Sarlis

NJ, Arnos KS, Nance WE, Yang Y, Zalewski CK, Brewer CC, Butman JA

and Griffith AJ: SLC26A4/PDS genotype-phenotype correlation in

hearing loss with enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct (EVA):

Evidence that Pendred syndrome and non-syndromic EVA are distinct

clinical and genetic entities. J Med Genet. 42:159–165. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li Q, Zhu QW, Yuan YY, Huang SS, Han DY,

Huang DL and Dai P: Identification of SLC26A4 c.919-2A>G

compound heterozygosity in hearing-impaired patients to improve

genetic counseling. J Transl Med. 10:2252012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

22

|

Sun SC, Liu YX, Peng YS, Li HF and Xie CY:

Analysis of GJB2 gene coding sequence in patients with nonsyndromic

hearing loss. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 28:409–413.

2011.In Chinese. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dai P, Stewart AK, Chebib F, Hsu A,

Rozenfeld J, Huang D, Kang D, Lip V, Fang H, Shao H, et al:

Distinct and novel SLC26A4/Pendrin mutations in Chinese and U.S.

patients with nonsyndromic hearing loss. Physiol Genomics.

38:281–290. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chun JY, Shin SK, Min KT, Cho W, Kim J,

Kim SO and Hong SP: Performance evaluation of the TheraTyper-GJB2

assay for detection of GJB2 gene mutations. J Mol Diagn.

16:573–583. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kent A, Turner MA, Sharland M and Heath

PT: Aminoglycoside toxicity in neonates: Something to worry about?

Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 12:319–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|