Introduction

Adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein

kinase (AMPK) is widely recognized as a central regulator of

cellular metabolism and energy homeostasis (1,2).

AMPK has been discovered as an enzyme that catalyzes the

phosphorylation of acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) carboxylase, which

regulates lipid synthesis (2).

AMPK activity is upregulated by the elevation of the AMP/adenosine

triphosphate (ATP) ratio in response to various types of

physiological and pathological stress, resulting in restoring

cellular enzyme balance by ATP generating pathways (3). In addition, activated AMPK suppresses

ATP utilizing pathways. Therefore, AMPK is currently known to

regulate metabolic homeostasis throughout the body (2).

Bone metabolism is predominantly regulated by two

types of functional cells, osteoblasts and osteoclasts (4). The former cells are responsible for

bone formation, while the latter cells are responsible for bone

resorption. Constant bone mass is maintained by bone remodeling,

which comprises osteoclastic bone resorption followed by

osteoblastic bone formation. Disruption to bone remodeling can

result in metabolic bone disease, including osteoporosis.

Concerning the association between AMPK and bone metabolism, it has

been demonstrated that AMPK activation stimulates osteoblast

differentiation and bone formation, resulting in increased bone

mass (5). It has been previously

reported that vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis induced

by basic fibroblast growth factor is regulated by AMPK in

osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells (6). However, the precise role of AMPK in

osteoblasts remains to be fully elucidated.

Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is an essential protein

secreted from osteoblasts, which inhibits osteoclast activation and

its differentiation, and a member of the tumor necrosis factor

receptor family along with receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

(RANK) (7). OPG binds to RANK

ligand (RANKL) as a decoy receptor, and prevents RANKL from binding

to RANK, resulting in the suppression of bone resorption (7). It has been demonstrated that RANKL

knockout mice suffer from severe osteopetrosis (8), suggesting that RANKL is a key

regulator of osteoclastogenesis. The RANK/RANKL/OPG axis is

currently recognized as a major regulatory system for osteoclast

formation and activity (9).

Prostaglandins (PGs) are autocrine/paracrine

modulators in the bone metabolism (10). Among them, PGE2 has been

recognized as an important mediator of bone remodeling (11). It has been previously reported that

PGE2 stimulates OPG synthesis via the activation of p38

mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, p44/p42 MAP kinase and

stress activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK)

in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells (12). However, the detailed mechanism

underlying PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis in osteoblasts

remains to be fully elucidated.

In the present study, the involvement of AMPK in the

synthesis of OPG induced by PGE2 in osteoblast-like

MC3T3-E1 cells was investigated. The current study aimed to

investigate whether AMPK positively regulates the

PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis via the SAPK/JNK pathway

in these cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

PGE2 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St.

Louis, MO, USA). The mouse OPG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) kit was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis,

MN, USA). Compound C was obtained from Calbiochem; EMD Millipore

(Billerica, MA, USA). Polyclonal rabbit phosphorylated (p)-AMPKα

(Thr-172; cat. no. 2531), p-AMPKβ (Ser-108; cat. no. 4181),

p-acetyl-CoA carboxylase (cat. no. 3661), p38 MAP kinase (cat. no.

9212), p-p44/p42 MAP kinase (cat. no. 9101), p44/p42 MAP kinase

(cat. no. 9102), SAPK/JNK (cat. no. 9252) antibodies, and

monoclonal rabbit p-p38 MAP kinase (cat. no. 4511) and p-SAPK/JNK

(cat. no. 4668) antibodies, were purchased from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies (sc-25778) were obtained from

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The Enhanced

Chemiluminescence (ECL) Western Blotting Detection System was

purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Chalfont, UK).

Acrylamide monomer, Tris(hydroxymethyl)amino-methane, sodium

dodecyl sulfate (SDS), dithiothreitol and glycerol were obtained

from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). PGE2 was

dissolved in ethanol. Compound C was dissolved in dimethyl

sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich). The maximum concentration of ethanol or

dimethyl sulfoxide was 0.1%, which did not affect either the assay

for OPG or the detection of protein levels using western blot

analysis.

Cell culture

Cloned osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells, which were

originally derived from newborn mouse calvaria (13), were maintained as described

previously (14). Briefly, the

cells were cultured in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM;

Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. The cells were

seeded into 35-mm diameter dishes (5×104 cells/dish) or

90-mm diameter dishes (2×105 cells/dish) in α-MEM

containing 10% FBS. Following culture for five days, the medium was

exchanged for α-MEM containing 0.3% FBS. The cells were then used

for experiments after 48 h.

Assay for OPG

The cultured cells were pretreated with 0.3, 1, 3 or

10 µM compound C for 60 min, then stimulated with 10

µM of PGE2 or vehicle in 1 ml α-MEM containing

0.3% FBS, and were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The conditioned

medium was collected, and the OPG concentration in the medium was

measured using the mouse OPG ELISA kit according to the

manufacturer's protocol.

Western blot analysis

The cultured cells were pretreated with 1, 3 or 10

µM compound C for 60 min, and then were stimulated with 10

µM PGE2 or vehicle for 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, 30 or 60

min. The cells were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered

saline (Sigma-Aldrich) and then lysed, homogenized and sonicated

900 µl lysis buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 2%

SDS, 50 mM dithiothreitol and 10% glycerol. SDS-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis was performed by the method described by Laemmli

(15) in 10% polyacrylamide gels.

The protein was fractionated and transferred onto an Immun-Blot

polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Western blot analysis was performed as

described previously (16) using

p-AMPKα (Thr-172), p-AMPKβ (Ser-108), p-acetyl-CoA carboxylase,

p-p38 MAP kinase, p38 MAP kinase, p-p44/p42 MAP kinase, p44/p42 MAP

kinase, p-SAPK/JNK, SAPK/JNK and GAPDH antibodies as the primary

antibodies at a dilution of 1:1,000 in 5% milk in Tris-buffered

saline (20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl) with 0.1% Tween-20

(TBST) overnight at 4°C. Goat-anti rabbit IgG horseradish

peroxidase-labeled antibodies (074-1506; KPL, Inc., Gaithersburg,

MD, USA) were used as the secondary antibodies at a dilution of

1:1.000 in 5% milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Peroxidase

activity on the PVDF membrane was visualized on X-ray film (Super

RX; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) by means of the ECL Western Blotting

Detection System.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The cultured cells were pretreated with 10 µM

compound C or vehicle for 60 min, then were stimulated by 10

µM PGE2 or vehicle in α-MEM containing 0.3% FBS

for 3 h. Total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed into

complementary DNA using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and the Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase kit

(Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), respectively. RT-qPCR was

performed using a LightCycler system (version 2.0; Roche

Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) in capillaries with the FastStart

DNA Master SYBR Green I provided with the RightCycler FastStart DNA

kit (Roche Diagnostics). Sense and antisense primers for mouse OPG

or GAPDH mRNA were purchased from Takara Bio, Inc. (Otsu, Japan;

primer set ID, MA026526). Amplification of the correct PCR products

was confirmed by melting curve analysis according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The OPG mRNA levels were normalized to

those of GAPDH mRNA.

Densitometric analysis

A densitometric analysis of the protein expression

was performed using a scanner (GT-F600; Seiko Epson Corporation,

Nagano, Japan) and an ImageJ analysis software, version 1.48

(National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The

background-subtracted signal intensity of each phosphorylation

signal was normalized to the respective total protein signal and

plotted as the fold increase in comparison to control cells without

stimulation.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by an analysis of variance,

followed by the Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons between

pairs. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. All data are presented as the mean ±

standard error of triplicate determinations from three independent

cell preparations.

Results

Effects of PGE2 on the

phosphorylation of AMPK or acetyl-CoA carboxylase in MC3T3-E1

cells

It has been previously established that the

phosphorylation of AMPK is essential for its activation (17). Therefore, in order to clarify

whether AMPK is activated by PGE2 in osteoblast-like

MC3T3-E1 cells, the effect of PGE2 on the

phosphorylation of AMPK was investigated by western blot analysis.

PGE2 was observed to significantly induce the

phosphorylation of AMPKα (Thr-172) and AMPKβ (Ser-108). The effects

of PGE2 on the phosphory-lation of AMPK α and AMPKβ

reached their peak 1 min and 5 min subsequent to the stimulation,

respectively, and reduced thereafter (Fig. 1). It is widely accepted that AMPK

induces the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase as a direct

substrate of AMPK, and regulates it (2). Thus, the effect of PGE2 on

the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase was investigated in

MC3T3-E1 cells. PGE2 significantly induced the

phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and the effect on the

phosphorylation reached its peak 5 min subsequent to stimulation

(Fig. 1).

Effect of compound C on the

PGE2-stimulated OPG release in MC3T3-E1 cells

It has been previously reported that PGE2

stimulates OPG synthesis via the activation of p38 MAP kinase,

p44/p42 MAP kinase and SAPK/JNK in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells

(12). In order to elucidate

whether AMPK serves a role in the PGE2-induced synthesis

of OPG in MC3T3-E1 cells, the effect of compound C, an inhibitor of

AMPK (18), on the release of OPG

induced by PGE2 was investigated. Compound C, which by

itself had minimal effect on the levels of OPG, significantly

reduced the PGE2-stimulated OPG release in a

dose-dependent manner in the range between 0.3 and 10 µM

(Fig. 2). A 10 µM dose of

compound C resulted in an approximately 40% inhibition in the

PGE2-effect.

Effect of compound C on the

PGE2-stimulated phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA

carboxylase in MC3T3-E1 cells

In order to investigate whether compound C functions

as an inhibitor of AMPK in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells, the

effect of compound C on the PGE2-induced phosphorylation

of acetyl-CoA carboxylase was examined. Compound C significantly

suppressed the PGE2-induced phosphorylation of

acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Fig.

3).

Effect of compound C on the

PGE2-induced OPG mRNA expression in MC3T3-E1 cells

In order to elucidate whether the suppression of the

PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis by compound C is mediated

via transcriptional events in MC3T3-E1 cells, the effect of

compound C on the PGE2-induced expression levels of OPG

mRNA were investigated. Compound C was observed to significantly

reduce the PGE2-induced OPG mRNA expression (Fig. 4).

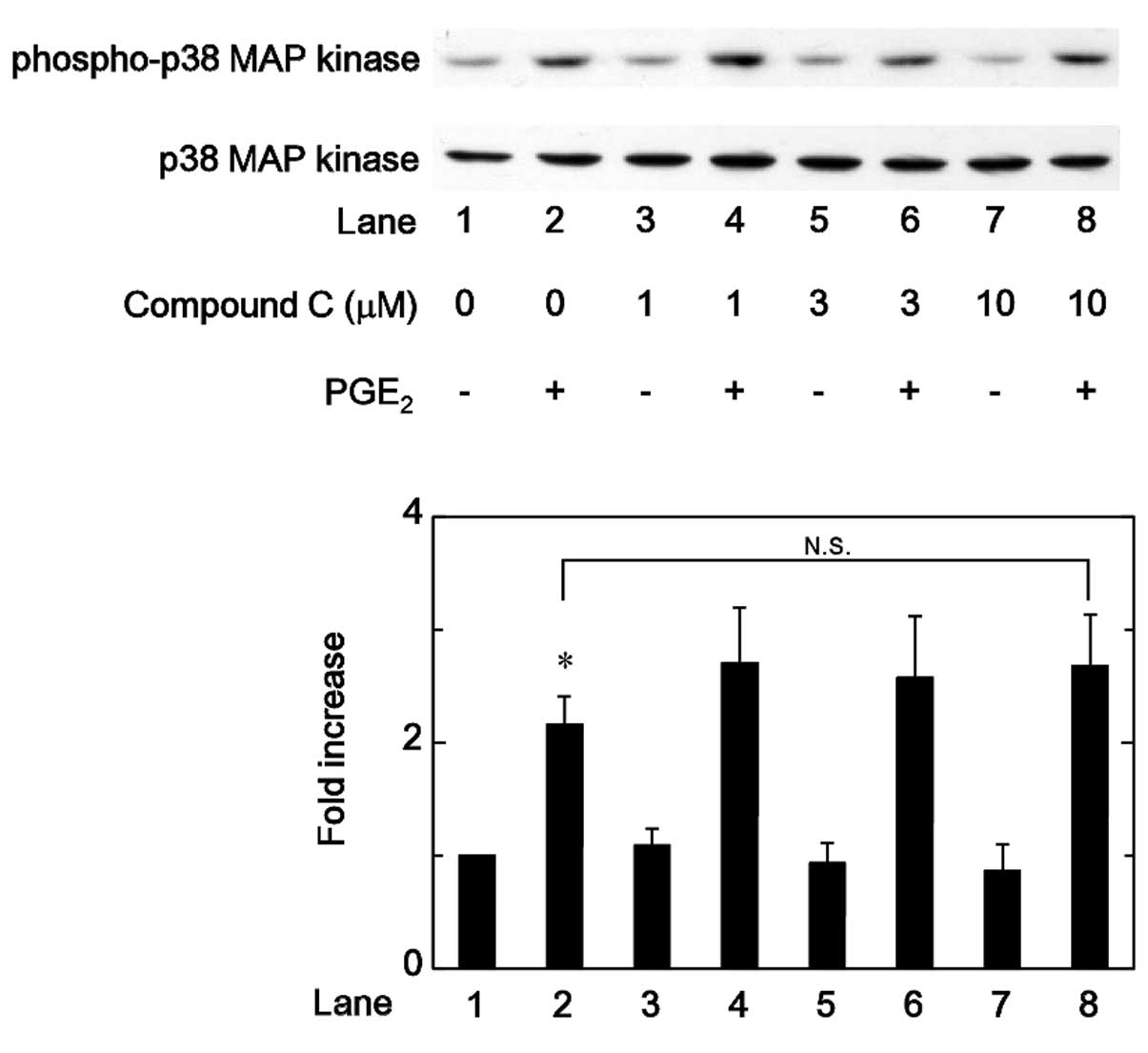

Effects of compound C on the

PGE2-stimulated phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase,

p44/p42 MAP kinase or SAPK/JNK in MC3T3-E1 cells

Regarding the intracellular signaling of

PGE2 in osteoblasts, it has been previously demonstrated

that PGE2 induces the activation of p38 MAP kinase,

p44/p42 MAP kinase and SAPK/JNK in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells,

and that these MAP kinases function as positive regulators in the

PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis in these cells (12). Therefore, the association between

AMPK and these MAP kinases in the PGE2-stimulated OPG

synthesis was investigated in MC3T3-E1 cells. Firstly the effects

of compound C on the PGE2-induced phosphorylation of p38

MAP kinase or p44/p42 MAP kinase were examined. However, compound C

was not observed to affect the PGE2-induced

phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase or p44/p42 MAP kinase in the

range between 1 and 10 µM (Figs. 5 and 6). By contrast, compound C significantly

attenuated the phosphorylation of SAPK/JNK induced by

PGE2 in a dose-dependent manner in the range between 1

and 10 µM (Fig. 7).

Discussion

In the present study, it was demonstrated that the

phosphorylation of AMPKα (Thr-172) and AMPKβ (Ser-108) was markedly

induced by PGE2 in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells. AMPK

exists as a heterotrimeric complex consisting of three subunits,

which are designated α, β and γ (1). Among the three AMPK subunits, the

α-subunit is recognized as a catalytic site, whereas the β- and

γ-subunits are regulatory sites (17). It is currently recognized that the

phosphorylation of the α-subunit is essential for AMPK activation,

while the phosphorylation of the β-subunit is required for correct

activation of AMPK (17). In the

current study, it was demonstrated that PGE2

significantly stimulated the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA

carboxylase, a direct substrate of AMPK, in MC3T3-E1 cells. The

time course of PGE2-induced AMPKα phosphorylation was

more rapid than that of acetyl-CoA carboxylase phosphorylation.

Based on these observations, it is suggested that PGE2

induces AMPK activation in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells.

In a previous study (12), it was reported that PGE2

stimulates OPG synthesis in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells. In the

present study, the involvement of AMPK in the

PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis in MC3T3-E1 cells was

investigated, and it was demonstrated that compound C, an inhibitor

of AMPK (18), reduced the release

of OPG induced by PGE2. It was additionally observed

that compound C significantly attenuated the phosphorylation of

acetyl-CoA carboxylase stimulated by PGE2. Therefore,

the observations of the current study suggest that

PGE2-activated AMPK acts as a positive regulator in OPG

release. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that compound C

significantly reduced the PGE2-mRNA expression levels of

OPG. Taking these observations into account, it is suggested that

PGE2 stimulates the synthesis of OPG, at least in part,

via AMPK activation in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells.

It is widely accepted that the MAP kinase

superfamily serves a central role in a variety of cellular

functions, including proliferation, differentiation and survival

(19). Three major MAP kinases,

p38 MAP kinase, p44/p42 MAP kinase and SAPK/JNK, are recognized as

central elements used by mammalian cells to transduce diverse types

of messages (20). Regarding the

signaling mechanism of the PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis

in osteoblasts, it has been previously demonstrated that

PGE2 stimulates the activation of p38 MAP kinase,

p44/p42 MAP kinase and SAPK/JNK in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells,

and that three MAP kinases are implicated in the

PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis (12). In order to establish how AMPK

functions in PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis in MC3T3-E1

cells, the association between AMPK and three MAP kinases was

investigated in the current study. It was demonstrated that

compound C suppressed the PGE2-induced phosphorylation

of SAPK/JNK without affecting the phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase

or p44/p42 MAP kinase. Based on the observations of the present

study, it is suggested that PGE2 induces the activation

of SAPK/JNK via AMPK in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells. In the

present study, it was demonstrated that the maximum effect of

PGE2 on AMPKα phosphorylation was observed at 1 min

subsequent to stimulation. By contrast, a previously study

demonstrated that PGE2-induced SAPK/JNK phosphorylation

reached its peak at 20 min subsequent to stimulation (12). The time course of the

PGE2-induced AMPK phosphorylation appears to be more

rapid than that of SAPK/JNK phosphorylation, suggesting that the

PGE2-induced activation of SAPK/JNK occurs subsequent to

AMPK activation. Taking the current and previous studies into

account, it is suggested that AMPK acts upstream of SAPK/JNK and

positively regulates the PGE2-stimulated OPG synthesis

in osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells. The potential mechanism of AMPK

in PGE2-induced OPG synthesis in osteoblasts

investigated here is summarized in Fig. 8.

AMPK is generally recognized as a key sensor in

cellular energy homeostasis (1).

Regarding AMPK in osteoblasts, it has been demonstrated that

metformin, an activator of AMPK, increases collagen-1 and

osteocalcin mRNA expression, stimulates alkaline phosphatase

activity and enhances cell mineralization in osteoblast-like

MC3T3-E1 cells (21). In addition,

AMPK activation reportedly inhibits palmitate-induced apoptosis in

osteoblasts (22). Furthermore,

AMPK has been observed to stimulate osteoblast differentiation via

induction of runt-related transcription factor 2 expression

(23). Thus, these observations

lead to the hypothesis that AMPK activation directs osteoblasts

toward stimulating bone formation. PGE2 is a well-known

autocrine/paracrine regulator of osteoblasts and acts as an

important mediator of bone remodeling (10). By contrast, OPG, which prevents the

biological effects of RANKL as a decoy receptor, negatively

regulates RANKL-mediated osteoclastic bone resorption (7). Therefore, the results of the present

study indicate that PGE2-activated AMPK in osteoblasts

functions as a modulator of bone metabolism via OPG synthesis,

resulting in the upregulation of bone formation, and these results

may provide a novel insight into bone metabolism. Further

investigation would be necessary to clarify the exact roles of AMPK

in bone metabolism.

The results of the current study indicate that AMPK

functions as a positive regulator in PGE2-stimulated OPG

synthesis via SAPK/JNK activation in osteoblasts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Yumiko Kurokawa

for her technical assistance. The current study was supported in

part by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry

of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (grant no.

19591042) and the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the

National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Japan (grant nos.

23-9 and 25-4).

References

|

1

|

Fogarty S and Hardie DG: Development of

protein kinase activators: AMPK as a target in metabolic disorders

and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1804:581–591. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mihaylova MM and Shaw RJ: The AMPK

signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and

metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 13:1016–1023. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rutter GA and Leclerc I: The AMP-regulated

kinase family: Enigmatic targets for diabetes therapy. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 297:41–49. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Karsenty G and Wagner EF: Reaching a

genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Dev

Cell. 2:389–406. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Shah M, Kola B, Bataveljic A, Arnett TR,

Viollet B, Saxon L, Korbonits M and Chenu C: AMP-activated protein

kinase (AMPK) activation regulates in vitro bone formation and bone

mass. Bone. 47:309–319. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kato K, Tokuda H, Adachi S,

Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Natsume H, Yamakawa K, Gu Y, Otsuka T and

Kozawa O: AMP-activated protein kinase positively regulates

FGF-2-stimulated VEGF synthesis in osteoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 400:123–127. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley

M, Chang MS, Lüthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, et

al: Osteoprotegerin: A novel secreted protein involved in the

regulation of bone density. Cell. 89:309–319. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL,

Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G,

Itie A, et al: OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis,

lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature.

397:315–323. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Theoleyre S, Wittrant Y, Tat SK, Fortun Y,

Redini F and Heymann D: The molecular triad OPG/RANK/RANKL:

Involvement in the orchestration of pathophysiological bone

remodeling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15:457–475. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hikiji H, Takato T, Shimizu T and Ishii S:

The roles of prostanoids, leukotrienes and platelet-activating

factor in bone metabolism and disease. Prog Lipid Res. 47:107–126.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhu Z, Fu C, Li X, Song Y, Li C, Zou M,

Guan Y and Zhu Y: Prostaglandin E2 promotes endothelial

differentiation from bone marrow-derived cells through AMPK

activation. PloS One. 6:e235542011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yamamoto N, Tokuda H, Kuroyanagi G,

Mizutani J, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Kondo A, Kozawa O and Otsuka T:

Regulation by resveratrol of prostaglandin E2-stimulated

osteoprotegerin synthesis in osteoblasts. Int J Mol Med.

34:1439–1445. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sudo H, Kodama HA, Amagai Y, Yamamoto S

and Kasai S: In vitro differentiation and calcification in a new

clonal osteogenic cell line derived from newborn mouse calvaria. J

Cell Biol. 96:191–198. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kozawa O, Tokuda H, Miwa M, Kotoyori J and

Oiso Y: Cross-talk regulation between cyclic AMP production and

phosphoinositide hydrolysis induced by prostaglandin E2

in osteoblast-like cells. Exp Cell Res. 198:130–134. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Laemmli UK: Cleavage of structural

proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4.

Nature. 227:680–685. 1970. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kato K, Ito H, Hasegawa K, Inaguma Y,

Kozawa O and Asano T: Modulation of the stress-induced synthesis of

hsp27 and alpha B-crystallin by cyclic AMP in C6 rat glioma cells.

J Neurochem. 66:946–950. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hawley SA, Davison M, Woods A, Davies SP,

Beri RK, Carling D and Hardie DG: Characterization of the

AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver and

identification of threonine 172 as the major site at which it

phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem.

271:27879–27887. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X,

Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, et al: Role of

AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J

Clin Invest. 108:1167–1174. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kyriakis JM and Avruch J: Mammalian

mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways

activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 81:807–869.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Widmann C, Gibson S, Jarpe MB and Johnson

GL: Mitogen-activated protein kinase: Conservation of a

three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol Rev. 79:143–180.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Yano S, Yamauchi

M and Sugimoto T: Metformin enhances the differentiation and

mineralization of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells via AMP kinase

activation as well as eNOS and BMP-2 expression. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 375:414–419. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kim JE, Ahn MW, Baek SH, Lee IK, Kim YW,

Kim JY, Dan JM and Park SY: AMPK activator, AICAR, inhibits

palmitate-induced apoptosis in osteoblast. Bone. 43:394–404. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jang WG, Kim EJ, Lee KN, Son HJ and Koh

JT: AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) positively regulates

osteoblast differentiation via induction of Dlx5-dependent Runx2

expression in MC3T3E1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

404:1004–1009. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|