Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection contributes to

human carcinogenesis, particularly in the development of lymphoma,

nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) and gastric cancer (1). EBV is a γ-herpes virus and infects B

cells of the immune system and epithelial cells. EBV latently

persists in the host B cells for life (2) and thus, EBV is estimated to infect

>90% of the population worldwide (2). In a small number of infected cell

populations, EBV infection can transform B cells to lymphoma cells

(3) or epithelial cells to

nasopharyngeal cancer cells (4).

Furthermore, ~10% of gastric cancer worldwide was associated with

EBV infection and this subtype of gastric cancer is termed

EBV-associated gastric cancer (EBVaGC) (5,6).

However, the molecular mechanism by which EBV infection causes

these malignancies remains to be defined.

Molecularly, the BamHI-A rightward frame 1

(BARF1) is an EBV gene that is expressed early in the EBV lytic

cycle and shares 38% primary amino acid sequence homology with the

bcl-2 proto-oncogene product (7).

The constitutive expression of BARF1 protein was able to

immortalize lymphoblast cells and prolong cell survival (8). The carcinogenic activity of the

oncogene c-myc is obligatory for the development of Burkitt

lymphoma and previous studies suggested that BARF1 expression is

required to inhibit c-myc-induced apoptosis and exhibits a synergic

role in mediating the effect of Bcl-2 and c-myc during B cell

transformation (9–13). BARF1 protein is also involved in

the regulation of microvessel density (MVD) and micro-lymphatic

vessel density (MLVD) (14,15).

Furthermore, MVD and MLVD are strongly associated with cancer

metastasis and with the survival of cancer patients (14). In addition, during EBV latency,

there are >8 EBV encoded proteins and several non-coding RNAs

expressed in cells (e.g., two EBV encoded small RNAs, termed EBER1

and EBER2), nuclear antigens and membrane proteins (16). Latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and

LMP2A are two EBV latent membrane proteins, which function as

constitutively active receptors independent of ligand binding and

manipulate the signaling pathways for B cell activation and

differentiation in order to sustain the long-life of EBV-positive

cells (17). The carboxyl terminus

of LMP1 contains consensus tumor necrosis factor

receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-binding domains, which can

constitutively activate signal transducers and activators of

transcription (STAT), janus kinase (JNK), and nuclear factor

(NF)-κB pathways for cell survival and growth (18). Although, the oncogenic role of LMP1

is well established, its roles in microvessel and micro-lymphatic

vessel formation are less clear. Thus, the present study assessed

the EBV infection in NPC and gastric cancer tissue samples, and

then analyzed the levels of MVD and MLVD to identify their

association with the clinicopathological features of the patients.

This study may provide a novel insight into the oncogenic role of

EBV in NPC and gastric cancer.

Patients and methods

Patients and tissue samples

A total of 600 gastric cancer and 75 NPC tissues

were collected. All tumor tissue specimens were histologically

confirmed and retrieved from the Department of Pathology, The

Shandong Provincial Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research

(Jinan, China) and The Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical

College (Jining, China) between 2008 and 2012. The present study

was approved by the Institutional review boards of The Shandong

Provincial Institute of Cancer Prevention and Research and The

Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical College. All patients

provided informed consent to participate in this study.

Tissue specimens from each patient were fixed in 10%

buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin (Shijiazhuang Chemical

Technology Co., Ltd., Shijiazhuang, China), and then cut into

serial sections (5 µm). One of the consecutive sections was

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Shanghai Biological

Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for confirmation of

diagnosis, while others were subjected to in situ

hybridization to detect EBV RNA or immunohisto-chemistry to detect

the expression of LMP1, BARF1, vascular endothelial growth factor-C

(VEGF-C), lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor-1

(LYVE-1) and CD34.

In situ hybridization and

immunohistochemistry

For in situ hybridization, an ISH-5022 EBER

kit was used (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.; OriGene Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China). A labeled

oligonucleotide probe complementary to EBER1 was used to detect the

EBER1 as positive REBV infection. Briefly, tissue sections were

deparaffinized and rehydrated, and then hybridized to a labeled

probe according to the manufacturer's instructions. Tissue sections

without probe hybridization were used as negative controls. For

immunohistochemistry, tissue sections were deparaffinized by 2

times incubation in xylenol for 10 min at room temperature and

dehydrated in a series of ethanol (100, 75 and 50%). Sections were

then incubated in 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room

temperature and subsequently subjected twice to antigen repair in

0.01 M acid buffer (pH 6.0) using a microwave at 92–98°C for 5 min,

with a 10 min break between incubations. Sections were washed in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubated with normal goat serum

for 15 min at room temperature, and further incubated with primary

antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were

rabbit monoclonal anti-LMP1 (cat. no. ZM-0386), rabbit monoclonal

anti-BHRF1 (cat. no. ZA-0627), rabbit monoclonal anti-VEGF-C (cat.

no. ZA-0266), mouse monoclonal anti-LYVE-1 (cat. no. ZA-0483) and

mouse monoclonal anti-CD34 (cat. no. ZM-0046) (dilution used for

all was 1:200; Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

OriGene Technologies, Inc.). The sections were washed 3 times with

PBS and incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse (cat. no. BA1001) or

anti-rabbit (cat. no. BA1003) secondary antibodies (dilution used

for all was 1:200; Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Beijing,

China) for 30 min at room temperature, and subsequently visualized

by incubation of tissue sections with a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine

solution (Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; OriGene

Technologies, Inc.). Sections were counterstained with H&E,

mounted with a coverslip and visualized using the Olympus CX23

light microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Review and scoring of stained tissue

sections

All tissue samples were reviewed and scored blindly

by two pathologists, and the pathology of each tissue section was

confirmed. To assess the in situ hybridization data,

negative controls were indicated as the sections without any

staining, and positive controls were indicated as the stained

sections with appropriate nuclear localization. To score

immunohistochemical data, the two pathologists reviewed at least

ten x400 fields and counted staining intensity and percentage of

positive cells vs. total cells. The staining intensity was judged

as no staining, −; light brown, +; brown, ++; and strong brown,

+++. The percentage of positive cells <10% was considered as

negative and the detailed information is as follows: <10%, −;

11–25%, +; 26–50%, ++; >50%, +++. These two scores were added

together to form a total score, high (score ≤2+) vs. low expression

of a protein.

Quantitative measurement of MVD and MLVD

levels in tissue specimens

MVD and MLVD were visualized using immunostaining of

the tissue sections with CD34 and LYE-1 antibodies, respectively,

to perform morphometric analysis. The stained sections were

reviewed and scored by two pathologists in a blind manner, under a

CX23 light microscope. Briefly, the pathologists reviewed the

sections under a ×100 magnification and then selected 5 high power

fields (×400 magnification) to capture images. CD34 immunostaining

was used to visualize microvascular endothelial cells, while LYVE-1

is specifically expressed in microlymphatic endothelial cells.

Under the CX23 light microscope, any brown colored endothelial

cells or microvascular endothelial cells observed in a cluster was

counted as one microvessel. Their branches were also counted as a

microvessel as long as the structures were not connected. However,

if the lumen had >8 red blood cells or the vessel had a muscular

and vascular wall, this vessel was not counted. MVD was calculated

as the mean number of microvessels from five ×200 microscopic

fields. Furthermore, micro-lymphatic vessels were labeled by

anti-LYVE-1 antibody and reviewed and counted as same as MVD.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data were

analyzed using the Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Count data were

presented as frequency and percentage, and analyzed by

χ2 analysis or Fisher's exact test. Measurement data

were presented as the mean/median ± standard deviation. Data with

normal distribution were analyzed by an F-test or t-test. Data with

uncommon distribution were analyzed by a non-parametric test or

Wilcoxon rank test.

Results

EBV infection is associated with

clinicopathological characteristics of patients

EBV infection has been linked to EBVaGC and NPC

(5,19); thus, in situ hybridization

was performed to detect EBV-encoded small RNA 1 (EBER1) as the

indication of EBV infection. Among the 600 gastric cancer tissue

specimens, 30 positive cases of EBV infection were identified

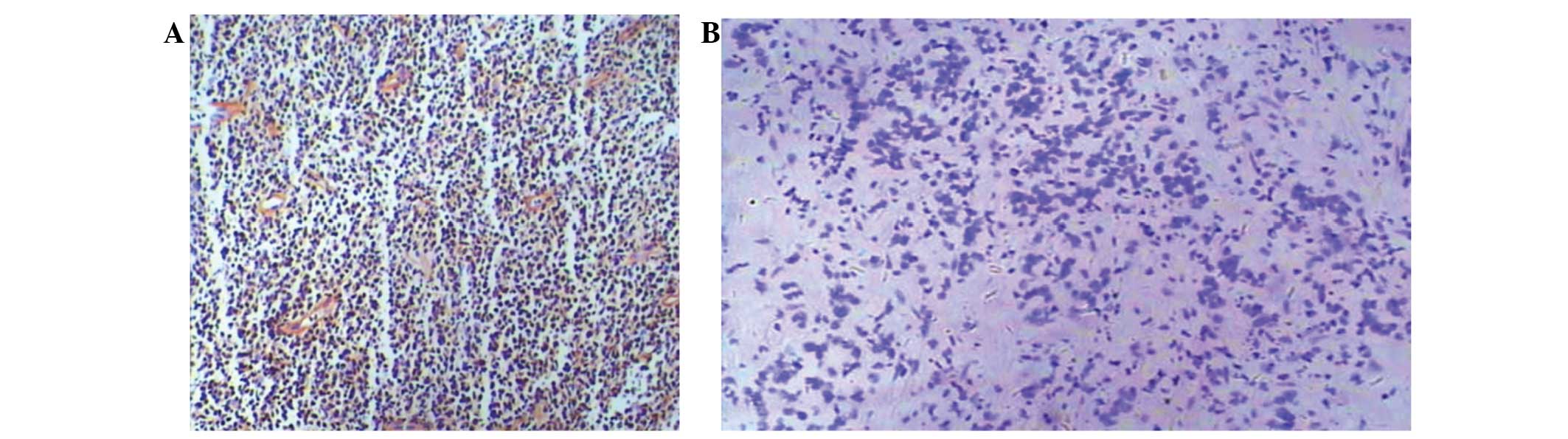

(Fig. 1A and Table I). Compared with negative staining,

ISH positive particles had deep purple blue staining present in the

nuclei (Fig. 1B). EBV infection

was shown to be correlated with the age of the patient (P=0.073),

tumor differentiation (P<0.0001), tumor location (P<0.0001)

and lymph node metastasis (P<0.0001; Table I). The data suggest that EBV

infection only occurs in a small percentage of gastric cancers

(5%).

| Table IAssociation of EBV infection with

clinicopathological characteristics from patients with gastric

cancer. |

Table I

Association of EBV infection with

clinicopathological characteristics from patients with gastric

cancer.

| Factor | No. of cases

(n=600) | No. of EBV-positive

cases (n=30) | No. of EBV-negative

cases (n=570) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Gender | | | | | 0.049 |

| Male | 384 | 25 | 359 | 3.87 | |

| Female | 216 | 5 | 211 | | |

| Age (years) | | | | | 0.073 |

| <45 | 32 | 4 | 32 | 2.24 | |

| 45–60 | 223 | 13 | 210 | | |

| >60 | 345 | 13 | 334 | | |

| Tumor

differentiation | | | | | <0.0001 |

| Well | 68 | 8 | 60 | 15.69 | |

| Moderate | 124 | 12 | 112 | | |

| Poor | 408 | 10 | 398 | | |

| Tumor location | | | | | <0.0001 |

| Gastric cardia

region | 102 | 12 | 90 | 14.99 | |

| Gastric body

region | 139 | 10 | 129 | | |

| Gastric antral

region | 359 | 8 | 351 | | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | | 0.0001 |

| Yes | 580 | 21 | 559 | 40.39 | |

| No | 20 | 9 | 11 | | |

Furthermore, in 75 patients with NPC, 61 patients

were positive for EBV infection (Table II). EBV infection was not shown to

be correlated with any of the clinicopathological characteristics

investigated (Table II).

| Table IIAssociation of EBV infection with

clinicopathological characteristics of patients with nasopharingeal

carcinoma. |

Table II

Association of EBV infection with

clinicopathological characteristics of patients with nasopharingeal

carcinoma.

| Factor | No. of cases

(n=75) | No. of EBV-positive

cases (n=61) | No. of

EBV-negativecases (n=14) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Gender | | | | | 0.79 |

| Male | 59 | 50 | 9 | 0.070 | |

| Female | 16 | 11 | 5 | | |

| Age (years) | | | | | 0.311 |

| <45 | 17 | 14 | 3 | 2.333 | |

| 45–60 | 36 | 35 | 1 | | |

| >60 | 22 | 11 | 11 | | |

| Pathology | | | | | |

| Keratinizing

squamous cell carcinoma | 8 | 7 | 10 | 0.016 | 0.90 |

| Non-keratinizing

carcinoma | 67 | 54 | 24 | | |

Expression of the EBV-associated proteins

LMP1 and BHFR1 is correlated with MLVD rather than MVD in patients

with EBVaGC

Expression of the EBV-associated proteins LMP1 and

BHFR1 and markers of MVD and MLVD (CD34 and LYVE-1) was then

further analyzed in the tissue specimens. Morphometric image

analysis of CD34 and LYVE-1 was used to visualize MVD and MLVD. The

data showed that MVD and MLVD were not associated with TNM stage

and lymph node metastasis in patients with EBVaGC (Table III). In the 30 patients with

EBVaGC, only one case showed weak LMP1 expression, but 17 cases

(56.7%) showed BARF1 expression (Fig.

2 and Table IV). BARF1

expression was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis

of EBVaGC. Among the 30 patients with EBVaGC, 18 patients (60%)

were VEGF-C positive (data not shown). The expression of VEGF-C was

not associated with lymph node metastasis. BARF1 expression was

associated with MLVD but not MVD. These data suggest that EBV could

infect lymphatic vessels and induce micro-lymphatic vessel

formation. Expression of VEGF-C was associated with MVD and MLVD

(data not shown).

| Table IIIAssociation of MVD and MLVD levels

with clinicopathological characteristics of patients with

Epstein-Barr-associated gastric cancer. |

Table III

Association of MVD and MLVD levels

with clinicopathological characteristics of patients with

Epstein-Barr-associated gastric cancer.

| Factor | n | MVD | P-value | MLVD | P-value |

|---|

| Gender | | | 0.408 | | 1.000 |

| Male | 25 | 32±2.3 | | 3.1±0.9 | |

| Female | 5 | 33±3.1 | | 3.1±1.4 | |

| TNM stage | | | 0.402 | | 0.128 |

| I/II | 10 | 32±3.1 | | 2.5±0.9 | |

| III/IV | 20 | 33±3.0 | | 3.5±1.9 | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | 0.111 | | 1.000 |

| Negative | 9 | 32±3.4 | | 3.2±0.9 | |

| Positive | 21 | 34±2.9 | | 3.0±1.7 | |

| Table IVAssociation of BARF1 and VEGF-C

expression with MVD and MLVD level in Epstein-Barr-associated

gastric cancer. |

Table IV

Association of BARF1 and VEGF-C

expression with MVD and MLVD level in Epstein-Barr-associated

gastric cancer.

| Expression | n | MVD | P-value | MLVD | P-value |

|---|

| BARF1 | | | 1.000 | | 0.000 |

| Negative | 13 | 29±3.1 | | 1.0±0.6 | |

| Positive | 17 | 29±2.3 | | 3.4±0.9 | |

| VEGF-C | | | 0.000 | | 0.000 |

| Negative | 12 | 23±4.8 | | 1.1±0.8 | |

| Positive | 18 | 31± 4.1 | | 3.1±0.4 | |

Expression of the EBV-associated proteins

LMP1 and BHFR1 was correlated with MLVD rather than MVD in patients

with NPC

Among 61 EBV positive NPC patients, there were 38

cases that were LMP1-positive (62.3%, Fig. 3). LMP1 expression was associated

with TNM stage (P=0.021) and lymph node metastasis (P=0.046). By

contrast, BARF1 was only expressed in 8 cases (13.3%) and BARF1

expression was not identified to be associated with the analyzed

factors. Moreover, VEGF-C was expressed in 52 cases (85.2%) and

VEGF-C expression was associated with lymph node metastasis

(P<0.0001). The MVD level was not shown to be significantly

different between LMP1-positive and -negative cases (Tables V and VI). However, MLVD in the LMP1-positive

group was significantly higher than the LMP1-negative group. This

suggests that LMP1 may contribute to micro-lymphatic formation. MVD

and MLVD in the VEGF-C-positive group were higher than in the

negative group suggesting that VEGF-C may contribute to microvessel

and micro-lymphatic formation in NPC.

| Table VAssociation of BHRF1, LMP1 and VGGF-C

expression with the clinicopathological data of patients. |

Table V

Association of BHRF1, LMP1 and VGGF-C

expression with the clinicopathological data of patients.

| Factor | n | LMP1 expression

| VEGF-C expression

| BHRF1 expression

|

|---|

| Negative | Positive | P-value | Negative | Positive | P-value | Negative | Positive | P-value |

|---|

| Gender | | | | 0.931 | | | 0.893 | | | 0.914 |

| Male | 50 | 20 | 30 | | 7 | 43 | | 43 | 7 | |

| Female | 11 | 3 | 8 | | 2 | 9 | | 10 | 1 | |

| TNM stage | | | | 0.021 | | | 0.31 | | | 0.943 |

| I/II | 27 | 18 | 9 | | 6 | 21 | | 23 | 4 | |

| III/IV | 34 | 5 | 29 | | 3 | 31 | | 30 | 4 | |

| LN metastasis | | | | 0.046 | | | 0 | | | 0.752 |

| Negative | 14 | 10 | 2 | | 7 | 7 | | 12 | 2 | |

| Positive | 47 | 13 | 36 | | 2 | 45 | | 41 | 6 | |

| Table VIAssociation of LMP1 and VEGF-C

expression with MVD and MLVD levels in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. |

Table VI

Association of LMP1 and VEGF-C

expression with MVD and MLVD levels in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma.

| Expression | n | MVD | P-value | MLVD | P-value |

|---|

| LMP1 | | | 1.000 | | 0.046 |

| Negative | 23 | 59±3.1 | | 5.0±2.0 | |

| Positive | 38 | 59±5.3 | | 6.4±2.9 | |

| VEGF-C | | | 0.000 | | 0.000 |

| Negative | 9 | 53±4.8 | | 4.1±1.8 | |

| Positive | 52 | 61±4.1 | | 8.1±3.0 | |

Discussion

EBVaGC is a recently identified cancer type that may

be caused by EBV infection (19).

The present study further demonstrated that EBV infection

contributes to the development of a small percentage (5%) of

gastric cancers, although previous studies have shown that 10% of

worldwide gastric cancers were EBVaGC (6,20).

By contrast, the frequency of EBV infection in NPC was notably

higher, effecting 85% of the patients observed. Although the

frequency of EBV infection in EBVaGC and NPC was different, the

molecular mechanism of EBV infection in different types of cancer

may be the same. Thus, in this study expression of the

EBV-associated proteins LMP1 and BARF1 was further assessed in NPC

and EBVaGC tissue specimens for association with

clinicopathological data and with MVD and MLVD. It was demonstrated

that BARF1 expression was associated with lymph node metastasis and

MLVD in patients with EBVaGC. In NPC, LMP1 expression was

associated with TNM stage (P=0.011) and lymph node metastasis

(P=0.041). Only 13.3% cases were BARF1 positive and MLVD was

significantly higher in LMP1-positive cases than in LMP1-negative

cases. The data from the current study indicate that although EBV

infection is involved in the development of gastric cancer and NPC,

expression of EBV-associated proteins LMP1 and BARF1 may have

differential functions during the tumorigenesis of these two types

of cancer.

Generally, primary EBV infection occurs via the oral

route and establishes a lifelong virus carrier state, termed latent

infection (21). In latent

infection, infected cells only express a limited set of viral

genes, but can provide a survival advantage to the infected cell

(22). The latent infection can be

further divided into different subgroups due to specific viral

proteins (23). EBVaGC is

considered as a latency I EBV infection, while NPC can be both

latency I and II EBV infections (24,25).

Latency I infection is characterized by expression of EBV nuclear

antigen 1 (EBNA1), EBER1 and 2, and BamHI-A rightward

transcripts (BART) (4,26). In addition to latency I

transcripts, latency II infection can also express latent membrane

protein 1 (LMP1) (4,26). Our current data are consistent with

previous findings (4,26). Only one patient with weak LMP1

expression was identified in the 30 EBVaGC cases. By contrast, 38

NPC tissues in these 61 NPCs exhibited LMP1 expression. This

confirmed that the latency of EBV infection between EBVaGC and NPC

was different. Therefore, due to the different expression of viral

proteins, oncogenic mechanisms of EBV in EBVaGC and NPC may

differ.

Furthermore, tumor metastasis is the leading cause

of cancer-related mortality (27,28).

A greater understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying tumor

metastasis may aid the development of effective cancer therapies.

The initial site of cancer metastasis is usually the regional lymph

nodes (29,30). Clinical and experimental data

suggested that lymphoangiogenesis can greatly facilitate the

migration of tumor cells into the lymph nodes (31–33).

The present study demonstrated that MLVD was associated with NPC

lymph node metastasis and that EBV infection was associated with

MLVD. The association between EBV infection and MLVD was consistent

in EBVaGC and NPC. These data suggest that EBV infection may have a

common effect on the regulation of lymphoangiogenesis, although the

exact molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Further investigation is

required to clarify how EBV infection contributes to an increase in

MLVD.

EBV-positive epithelial malignancies show selective

and abundant expression of a viral gene that encodes BARF1 protein

(34). BARF1 expression was

usually low in lymphomas, but more frequent in EBV-associated

carcinomas. BARF1 may function as an oncogene in NPC, parallel to

the more widely investigated viral protein LMP1 (35). In EBV-positive gastric cancer,

BARF1 was expressed in the absence of LMP1, possibly functioning as

the predominant EBV oncogene in this disease (36). BARF1 expression was able to

immortalize and transform epithelial cells of different origins by

acting as a mitogenic growth factor, inducing cyclin-D expression

and upregulating anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, and in turn stimulating host

cell growth and survival (37). In

the current study, 13% of NPCs were positive for BARF1, whereas

BARF1 was expressed in 56.7% of EBVaGCs. This finding suggests that

BARF1 and LMP1 may have redundant functions in promoting

tumorigenesis in gastric cancer and in NPC.

The current study does have certain limitations. For

example, it is only a proof-of-principle descriptive study and

additional mechanistic data are required to support the current

findings. It remains to be determined how these two viral proteins

function differentially in these two types of human cancer or

whether EBV is involved in the development of EBV-positive gastric

cancer since EBV is estimated to infect >90% of the worldwide

population and EBV infection may be just bystander in these gastric

types of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the 973

Projects of China (grant no. 2011CB504302) and the Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 30872318). The authors would also

like to acknowledge the valuable comments from other members of the

laboratories.

References

|

1

|

Morales-Sánchez A and Fuentes-Pananá EM:

Human viruses and cancer. Viruses. 6:4047–4079. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xu X, Yang Z, Chen Q, Yu L, Liang S, Lü H

and Qiu Z: Comparison of clinical characteristics of chronic cough

due to non-acid and acid gastroesophageal reflux. Clin Respir J.

9:196–202. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ok CY, Papathomas TG, Medeiros LJ and

Young KH: EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the

elderly. Blood. 122:328–340. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Young LS and Rickinson AB: Epstein-Barr

virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer. 4:757–768. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tokunaga M, Land CE, Uemura Y, Tokudome T,

Tanaka S and Sato E: Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. Am J

Pathol. 143:1250–1254. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Takada K: Epstein-Barr virus and gastric

carcinoma. Mol Pathol. 53:255–261. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pfitzner AJ, Tsai EC, Strominger JL and

Speck SH: Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones

corresponding to transcripts from the Bam HI H and F regions of the

Epstein-Barr virus genome. J Virol. 61:2902–2909. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kelly GL, Long HM, Stylianou J, Thomas WA,

Leese A, Bell AI, Bornkamm GW, Mautner J, Rickinson AB and Rowe M:

An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively

expressed in transformed cells and implicated in burkitt

lymphomagenesis: The Wp/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog. 5:e10003412009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Taub R, Kirsch I, Morton C, Lenoir G, Swan

D, Tronick S, Aaronson S and Leder P: Translocation of the c-myc

gene into the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in human Burkitt

lymphoma and murine plasmacytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

79:7837–7841. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Corcoran

LM, Alexander WS, Cory S, Palmiter RD and Brinster RL: The c-myc

oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid

malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 318:533–538. 1985.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Magrath I: The pathogenesis of Burkitt's

lymphoma. Adv Cancer Res. 55:133–270. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Strasser A, Harris AW, Bath ML and Cory S:

Novel primitive lymphoid tumours induced in transgenic mice by

cooperation between myc and bcl-2. Nature. 348:331–333. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Beverly LJ and Varmus HE: MYC-induced

myeloid leukemo-genesis is accelerated by all six members of the

antiapoptotic BCL family. Oncogene. 28:1274–1279. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lee KM, Danuser R, Stein JV, Graham D,

Nibbs RJ and Graham GJ: The chemokine receptors ACKR2 and CCR2

reciprocally regulate lymphatic vessel density. EMBO J.

33:2564–2580. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P and Folkman J:

Clinical application of antiangiogenic therapy: Microvessel

density, what it does and doesn't tell us. J Natl Cancer Inst.

94:883–893. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yates JL, Warren N and Sugden B: Stable

replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various

mammalian cells. Nature. 313:812–815. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gires O, Zimber-Strobl U, Gonnella R,

Ueffing M, Marschall G, Zeidler R, Pich D and Hammerschmidt W:

Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus mimics a

constitutively active receptor molecule. EMBO J. 16:6131–6140.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dawson CW, Port RJ and Young LS: The role

of the EBV-encoded latent membrane proteins LMP1 and LMP2 in the

pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Semin Cancer Biol.

22:144–153. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Burke AP, Yen TS, Shekitka KM and Sobin

LH: Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the stomach with Epstein-Barr

virus demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction. Mod Pathol.

3:377–380. 1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Shibata D and Weiss LM: Epstein-Barr

virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 140:769–774.

1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shannon-Lowe C and Rowe M: Epstein Barr

virus entry; kissing and conjugation. Curr Opin Virol. 4:78–84.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tsao SW, Tsang CM, Pang PS, Zhang G, Chen

H and Lo KW: The biology of EBV infection in human epithelial

cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 22:137–143. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Woellmer A and Hammerschmidt W:

Epstein-Barr virus and host cell methylation: Regulation of

latency, replication and virus reactivation. Curr Opin Virol.

3:260–265. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen JN, He D, Tang F and Shao CK:

Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: A newly defined

entity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 46:262–271. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Frappier L: Role of EBNA1 in NPC

tumourigenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 22:154–161. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Robertson KD, Manns A, Swinnen LJ, Zong

JC, Gulley ML and Ambinder RF: CpG methylation of the major

Epstein-Barr virus latency promoter in Burkitt's lymphoma and

Hodgkin's disease. Blood. 88:3129–3136. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lauria R, Perrone F, Carlomagno C, De

Laurentiis M, Morabito A, Gallo C, Varriale E, Pettinato G, Panico

L, Petrella G, et al: The prognostic value of lymphatic and blood

vessel invasion in operable breast cancer. Cancer. 76:1772–1778.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kyzas PA, Geleff S, Batistatou A, Agnantis

NJ and Stefanou D: Evidence for lymphangiogenesis and its

prognostic implications in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J

Pathol. 206:170–177. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chua B, Ung O, Taylor R and Boyages J:

Frequency and predictors of axillary lymph node metastases in

invasive breast cancer. ANZ J Surg. 71:723–728. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Cunnick GH, Jiang WG, Gomez KF and Mansel

RE: Lymphangiogenesis and breast cancer metastasis. Histol

Histopathol. 17:863–870. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, Prevo

R, Janes L, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Alitalo K, Claffey K and Detmar

M: Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast

cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 7:192–198. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

He Y, Karpanen T and Alitalo K: Role of

lymphangiogenic factors in tumor metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1654:3–12. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Salven P, Mustjoki S, Alitalo R, Alitalo K

and Rafii S: VEGFR-3 and CD133 identify a population of CD34+

lymphatic/vascular endothelial precursor cells. Blood. 101:168–172.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Brink AA, Vervoort MB, Middeldorp JM,

Meijer CJ and van den Brule AJ: Nucleic acid sequence-based

amplification, a new method for analysis of spliced and unspliced

Epstein-Barr virus latent transcripts, and its comparison with

reverse transcriptase PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 36:3164–3169.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zheng H, Li LL, Hu DS, Deng XY and Cao Y:

Role of Epstein-Barr virus encoded latent membrane protein 1 in the

carcinogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Mol Immunol.

4:185–196. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

zur Hausen A, Brink AA, Craanen ME,

Middeldorp JM, Meijer CJ and van den Brule AJ: Unique transcription

pattern of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in EBV-carrying gastric

adeno-carcinomas: Expression of the transforming BARF1 gene. Cancer

Res. 60:2745–2748. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chang MS, Kim DH, Roh JK, Middeldorp JM,

Kim YS, Kim S, Han S, Kim CW, Lee BL, Kim WH and Woo JH:

Epstein-Barr virus-encoded BARF1 promotes proliferation of gastric

carcinoma cells through regulation of NF-kB. J Virol.

87:10515–10523. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|