Introduction

Impairment of articular hyaline cartilage, can lead

to different grades of disability depending on the functionality of

the joint, and the grade of cartilage degeneration and destruction

(arthritis). Acute trauma of a joint due to a sporting injury or

accident, or chronic degeneration of the cartilage due to age, are

the main and most frequent causes of severe impairment of articular

cartilage that can lead to final stages of osteoarthritis and

serious disability (1–3). The most common therapies [abrasion

arthroplasty, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI),

microfractures and arthroplasties] may not lead to complete

rehabilitation and there is always the risk of side effects, such

as infection of total arthroplasty and dislocation of the joint due

to stem misorientation or loosening (1–5).

On these grounds, to avoid severe osteoarthritis and

the requirement for arthroplasty surgery, research is being

conducted in the field of neochondrogenesis (2,5,6).

Neochondrogenesis is a procedure during which the body is

stimulated to form newly synthesized cartilage from mesenchymal

stem cells (MSCs), at a specific location (2,4).

Several lines of evidence suggest that neochondrogenesis may become

a promising alternative to prevent osteoarthritis. Studies on

skeleton metabolism have led to the identification of a number of

factors involved in cartilage formation by causing the

differentiation of MSCs into chondrocytes (7–10).

There are several approaches for administering these factors into

the point of interest in laboratory animals and humans. It has been

suggested that these factors can be administered directly into the

point of interest (damaged cartilage) with rather encouraging

results or in the form of a factor saturated scaffold (11,12).

In addition, in certain cases, apart from being saturated with

growth factors, scaffolds contain premature chondrocytes obtained

after the in vitro differentiation of autologous MSCs

isolated from the patient (13–17).

One of the most potent factors that has been

investigated for its ability to stimulate chondrogenesis in human

MSCs (hMSCs) is transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) (18). MSC transformation into chondrocytes

in this case is stimulated though activation (phosphorylation) of

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2) (19,20).

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is a potent

growth and survival factor in human cancer, and the gene gives rise

to multiple heterogeneous transcripts, IGF-1Ec among them, all

resulting in the mature form of IGF-1. While the physiological role

of IGF-1Ec is under debate, it has been known to participate in

skeletal muscle repair, as well as in the cardiac remodeling/repair

process (21,22).

Recent evidence suggests that the Ec peptide (PEc),

resulting from the proteolytic cleavage of the COO−

terminal of the IGF-1Ec isoform, is associated with ERK 1/2

activation in various cell lines with adverse effects, including

cellular proliferation, differentiation and satellite stem cell

mobilization prior to repair (23–27).

Also, there are indications that PEc participates in the healing

process by affecting the expression pattern of osteogenic and

adipogenic genes in MSCs, thus affecting differentiation during

wound healing, while the mechanism by which it promotes

proliferation and survival in cancer cells may in fact be mediated

by a unique receptor (28,29). Additionally, it has also been

suggested that IGF-1Ec expression is stimulated by tissue damage

leading to MSC attraction through PEc prior to repair, as was

determined by in vitro assays (30).

The aim of the present study was to examine the

effects of PEc on hMSCs and the possibility of increasing hyaline

cartilage formation, using PEc in combination with TGF-β1 to

stimulate MSC migration (PEc) and differentiation (TGF-β1)

simultaneously.

Materials and methods

hMSC isolation

Human bone marrow was collected from the scrape

material of three healthy donors aged 32, 37 and 29 years old, with

open femur fractures. The material was used after all the patients

filled in a written informed consent form. This study was approved

by the institutional ethics committee and all experimental

procedures conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was given

and explained to the patients after the surgery and during their

rehabilitation. The acquired marrow was briefly filtered through a

70-mm mesh and the resulting cells were cultured at a density of

25×106 per 75-cm2 flask in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The cells

were incubated in a standard issue tissue culture incubator (37°C

and 5% CO2). The media was changed 3 h after initial

culture and then every 8 h for the remaining 72 h. The adherent

cells were then trypsinized for 2 min at 25°C and examined for

expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and the mesenchymal

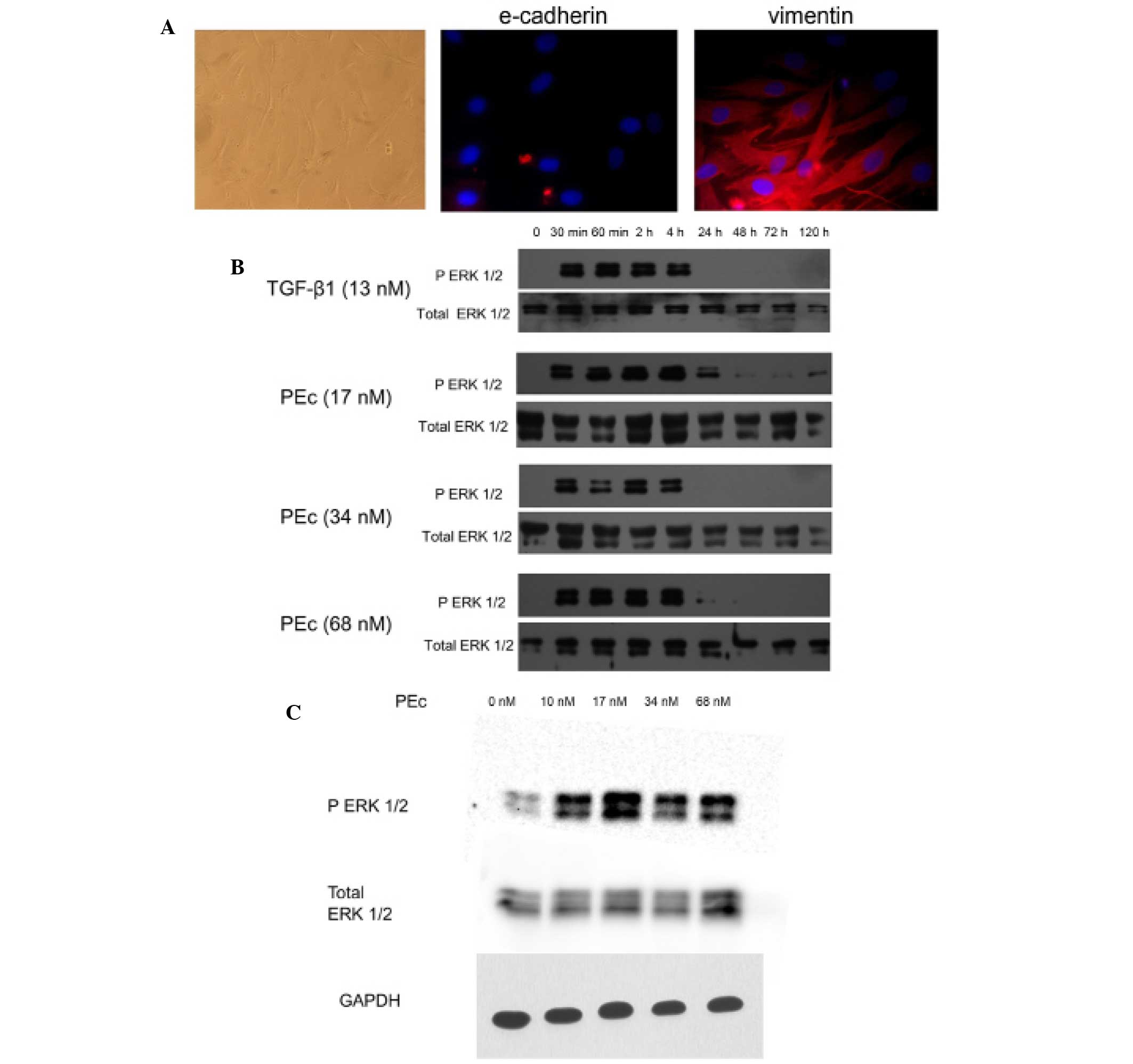

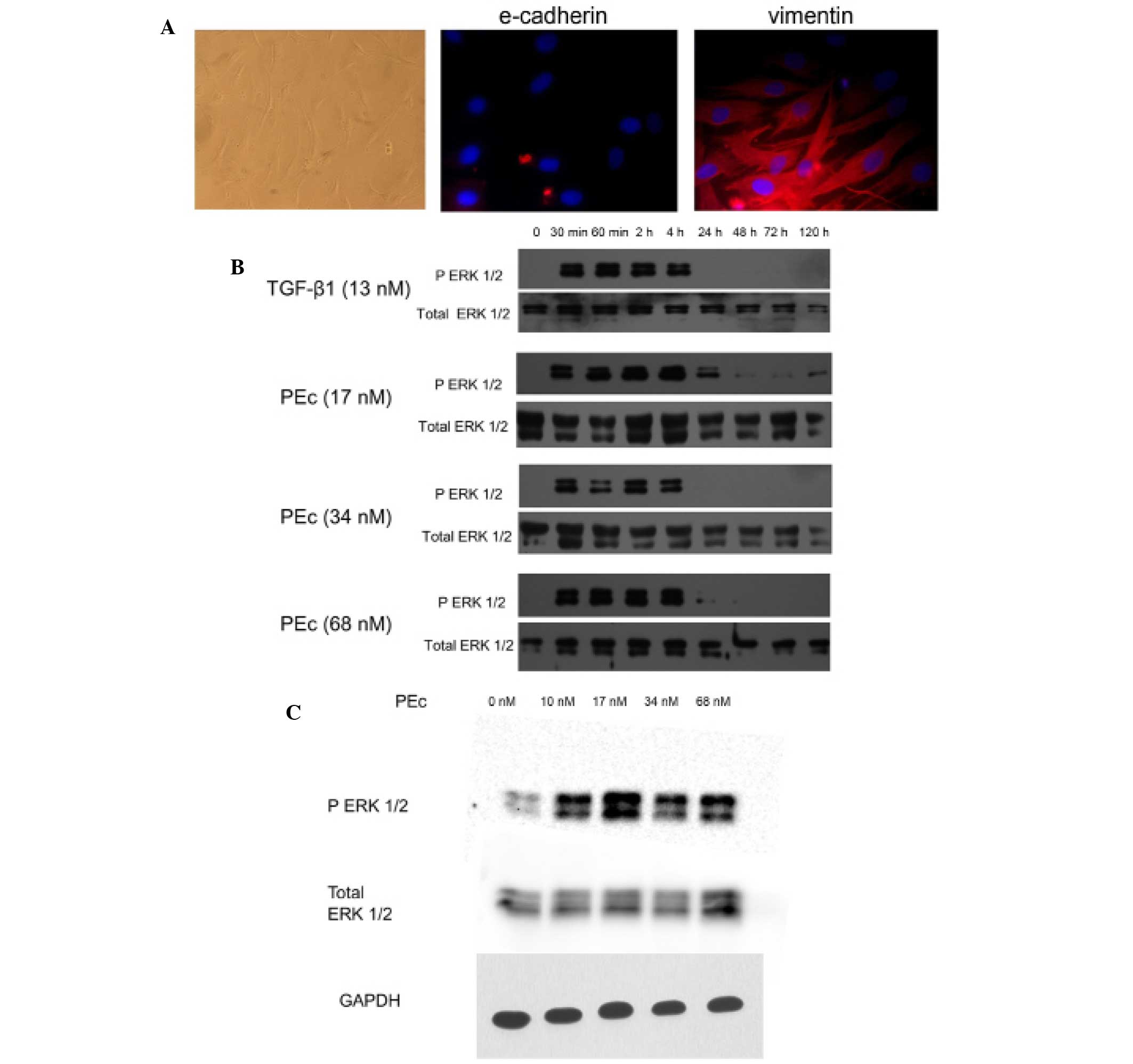

marker vimentin (Fig. 1A)

(31).

| Figure 1Effects of PEc on hMSC activation. (A)

Characterization of the freshly isolated hMSCs by

immunofluorescence (magnification, ×200). The cells obtained from

human bone marrow were examined for E-cadherin and Vimentin

expression. It was determined that these cells were not expressing

E-cadherin but were expressing vimentin at the protein level. In

addition, the cellular morphology as was determined by light

microscopy, was confirmatory to the mesenchymal nature of these

cells. (B) The effect of different concentrations of PEc on hMSCs

was examined by western blot analysis of ERK 1/2 phosphorylation,

at different time intervals. It was determined that PEc activates

ERK 1/2 whereas its optimum concentration (17 nM) was able to

maintain the ERK 1/2 phosphorylation for 24 h, longer than that

obtained with TGF-β1 treatment (4 h). (C) The optimal PEc

concentration (17 nM) was determined by western blot analysis of

ERK 1/2 phosphorylation at 30 min. hMSCs, human mesenchymal stem

cells; PEc, Ec peptide; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase;

TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde

3-phosphate dehydrogenase. |

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells cultured on culture slides (8-well, BD

Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were stained by an indirect

immunofluorescence method. Briefly, cells were rinsed in 1X

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with ice-cold 80%

methanol for 10 min at room temperature. They were permeabilized

with 1X PBS plus 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO,

USA) for 10 min. They were then incubated with primary antibodies

overnight at 4°C: Polyclonal rabbit anti-E-cadherin (1:100;

ab15148; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or monoclonal mouse anti-vimentin

(1:100; ac8978330; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in 1X PBS. After 3 washes

with 1X PBS, each lasting 5 min at room temperature, cells were

incubated for 30 min with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to the

fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 dye (1:2,000, ab150077, Abcam,

Cambridge, UK) or with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to the

fluorescent Alexa 555 dye (1:2,000, A-21422, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in 1X PBS. After 3 washes with 1X PBS, each

lasting 5 min at room temperature, samples were stained with DAPI

(1 μg/ml; Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA)

for viewing with an Olympus BX40 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo,

Japan).

Cell proliferation

For the Trypan Blue Exclusion assays, hMSCs were

plated at a cell density of 3.5×104 cells/well in 6-well

plates and cultured in DMEM and 10% FBS. After 24 and 48 h of

culture, the cell number was counted using a hemocytometer

(Celeromics Technologies, Cambridge, UK). A 0.4% solution of trypan

blue in PBS was prepared and 0.1 ml trypan blue solution was added

to 1 ml of cells. Immediately after, a hemocytometer was used to

count the number of blue stained cells and the number of total

cells. Blue staining cells are considered to be non-viable. Trypan

blue exclusion assays determine the actual number of living

cells.

Western blot analysis

Investigation of phosphorylated (p)-ERK 1/2 and

total ERK 1/2 expression in the isolated hMSCs. TGF-β1 (13 nM;

Biognos, Waterven, Belgium) and PEc (17, 34 or 68 nM; Eastern

Quebec Proteomic Core Facility, Sainte-Foy, Canada) were added in

tissue culture wells with hMSCs at intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4,

24, 48, 72 and 120 h. Proteins were then isolated using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with the addition of protease

and phosphatase inhibitors (all Sigma-Aldrich). Western blot

analysis was conducted after protein separation using 60 μg

sample loaded onto a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

(Sigma-Aldrich). Proteins were transferred to polyvinlydene

fluoride membranes and blocked in 0.1% milk in Tris-buffered

saline. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in the

following primary antibodies: Rabbit anti-Phospho-p44/42 MAPK

(Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (1:2,000; 9101; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc., Beverly, MA, USA), and rabbit anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2)

(1:2,000; 9102; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Subsequently,

membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody

(1:2,000; AP132P; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Detection was

conducted using the Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent

substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The expression levels of Collagen (Col) I, Col II

and Col X were assessed by RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR was performed in the

Biorad IQ5 multicolor Real Time PCR detection system, using

Sybergreen Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). RNA extracts were

obtained using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Each RT reaction was conducted using 1.5 mg RNA mixed with 10

mmol/l dNTPs (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 0.5

μg/ml oligo dTs (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 3 mg/ml

random hexamer primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), it was

heated at 65°C for 5 min and quick-chilled on ice. The RT Mix

containing 200 U/μl M-MuLV ProtoScript II Reverse

Transcriptase, 5X ProtoScript II RT Reaction buffer, 0.1 mol/l DTT

and murine RNAse inhibitor (40 U/μl) (New England Biolabs)

was then added, and the reactants were incubated at 42°C for 50 min

and 70°C for 20 min. Subsequently, each reaction was obtained in 20

μl using 10 μl KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master mix (Kapa

Biosystems Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA), 2 μl cDNA and 0.3

μmol/l primers (23,24).

The sequences for the primers used were as follows: Forward:

5′-AGGGCTCCAACGAGATCGAGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-AGGAAGCAGACAGGGCCA-3′

for Col I; forward: 5′-CTATCTGGACGAAGCAGCTGGCA-3′ and reverse:

5′-ATGGGTGCAATGTCAATGATGG-3′ for Col II; forward:

5′-GCTAAGGGTGAAAGGGGTTC-3′ and reverse: 5′-CTCCAGGATCACCTTTTGGA-3′

for Col X; and forward: 5′-CCTCGCCTTTGCCGA-3′ and reverse:

5′-TGGTGCCTGGGGCG-3′ for β-actin (Eurofins Genomics GmbH,

Ebersberg, Germany).

The PCR conditions were the same in all three cases:

95°C for 3 min for 1 cycle, 94°C for 3 sec, then 60°C for 30 sec

for 40 cycles, and 70°C for 15 sec for 50 cycles (increasing 0.5°C

after every cycle) to determine the melt curve. Each reaction was

performed in triplicate and values were normalized to β-actin. mRNA

levels were quantified using iQ5 Optical System Software (Bio-Rad)

and the ΔΔCq method (32).

Alcian blue

Cartilage matrix deposition in cells cultured in

six-well dishes was quantified by Alcian blue staining. Cells were

stained with Alcian blue (1% in 3% acetic acid; Sigma-Aldrich) for

30 min, washed three times for 2 min in 3% acetic acid, rinsed once

with 1X PBS, and solubilized in 1% SDS. The staining was separately

repeated without the final solubilization step. The absorbance at

605 nm was determined using a VersaMax microplate reader for

triplicate samples (33)

(Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). To avoid random

differentiation, the treatments were conducted in cells at 60–70%

confluency.

Migration/invasion assay

Cell migration and invasion were analyzed using the

Cultrex cell invasion assay (Trevigen Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, for the

invasion assay, the membrane in the upper chamber of the 96-well

plate was coated with 0.5X basement membrane matrix/Matrigel. For

the migration assay, the membrane was left uncoated. hMSCs were

starved in serum-free medium for 8 h prior to the assay, then

seeded at a density of 5×104 cells/well. After seeding

(24 h), the cells on the lower surface were dissociated by

aspiration and counted using a hemocytometer.

Wound healing assay

Isolated MSCs were cultured in DMEM supplemented

with 10% FBS and then seeded into 24-well tissue culture plate

wells at a density of 4×106 cells/well, so that after 24

h of growth, they should reach 90–95% confluency as a monolayer.

The monolayers were scratched with a sterilized 200 μl

pipette tip vertically across the center of the well. After

scratching, the wells were washed twice with 1X PBS to remove the

detached cells and replenished with fresh medium containing either

TGF-β1 (13 nM), PEc (17 nM) or TGF-β1 (13 nM)+PEc (17 nM).

Scratched monolayers replenished with just fresh medium were used

as control samples. Images were collected at 0, 8, 16, and 24 h

using a Olympus BX40 microscope. Afterwards, the tscratch software,

version 7.8 (Computational Science and Engineering Laboratory,

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, Switzerland) was

implemented in order to perform image analysis to measure the gap

areas.

Statistical analysis

Changes in gene expression levels and cell numbers

were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (SPSS v. 11

statistical package; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Where

significant F ratios were found (P<0.05), the means were

compared using Tukey's post-hoc tests. All data are presented as

the mean ± standard error of the mean. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effect of PEc on MSC stimulation

Exogenous administration of the synthetic human PEc

peptide stimulates the MSCs, as was determined by western blot

analysis to determine the expression of p-ERK 1/2. This was also

demonstrated for TGF-β1. Further analysis prior to determining the

optimum concentration of exogenous PEc, suggested that

administration of 17 nM PEc led to a prolonged phosphorylation time

of ERK 1/2 compared with the higher concentrations used in this

study (Fig. 1B).

Effect of PEc on MSC proliferation

Since PEc has previously been demonstrated to affect

cellular proliferation in various cell lines, the effect of PEc on

MSC proliferation was also examined. Exogenous administration of

PEc on hMSCs was not associated with a significant increase in cell

proliferation at any of the concentrations used (results not

shown).

Expression of collagen

Since ERK 1/2 phosphorylation is associated with

hMSC differentiation towards a chondrocytic fate, hMSCs treated

with the optimum concentrations of PEc and with PEc+TGF-β1 were

examined for their expression of Col I, which is mainly expressed

in tendons, ligaments and brittle cartilage, Col II that is the

basis of articular and hyaline cartilage, and Col X that is

expressed by hypertrophic chondrocytes during endochondral

ossification (34). It was

determined that the administration of PEc and PEc+TGF-β1 were

associated with a significantly lower expression of Col I at the

15th day compared with the effects of TGF-β1 alone, and they

presented similar levels of expression as the untreated hMSCs

(Fig. 2A).

| Figure 2Quantitative analysis of the mRNA of

Col I, Col II and Col X in hMSCs as assessed by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction, after the

administration of TGF-β1, PEc and the combination of both at

different time points (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 15 days). (A)

Administration of PEc (17 nM) and of PEc+TGF-β1 lead to

significantly lower expression of Col I compared with that obtained

by TGF-β1 treatment at day 15 (P<0.001). (B) PEc and PEc+TGF-β1

administration were also associated with significant elevation of

thew expression of Col II compared with that obtained by TGF-β1

(P=0.002). (C) No significant difference was observed in any of the

three treatments in respect to Col X expression.

*P<0.05, **P<0.005. hMSCs, human

mesenchymal stem cells; Col, collagen; TGF-β1, transforming growth

factor β1; PEc, Ec peptide. |

Col II expression was significantly higher in all

the conditions examined compared with the untreated hMSCs, through

the course of the study. Although PEc appears to be associated with

a significant increase in Col II at days 4, 6 and 8 compared with

the Col II levels obtained by TGF-β1 and PEc+TGF-β1 administration,

at day 10 and 15 no significant difference was identified in the

Col II expression stimulated by PEc, TGF-β1 and PEc+TGF-β1

treatments (Fig. 2B).

None of the factors examined were associated with a

significant increase in Col X through the course of the study

(Fig. 2C).

Differentiation of hMSCs into a

chondrocyte lineage

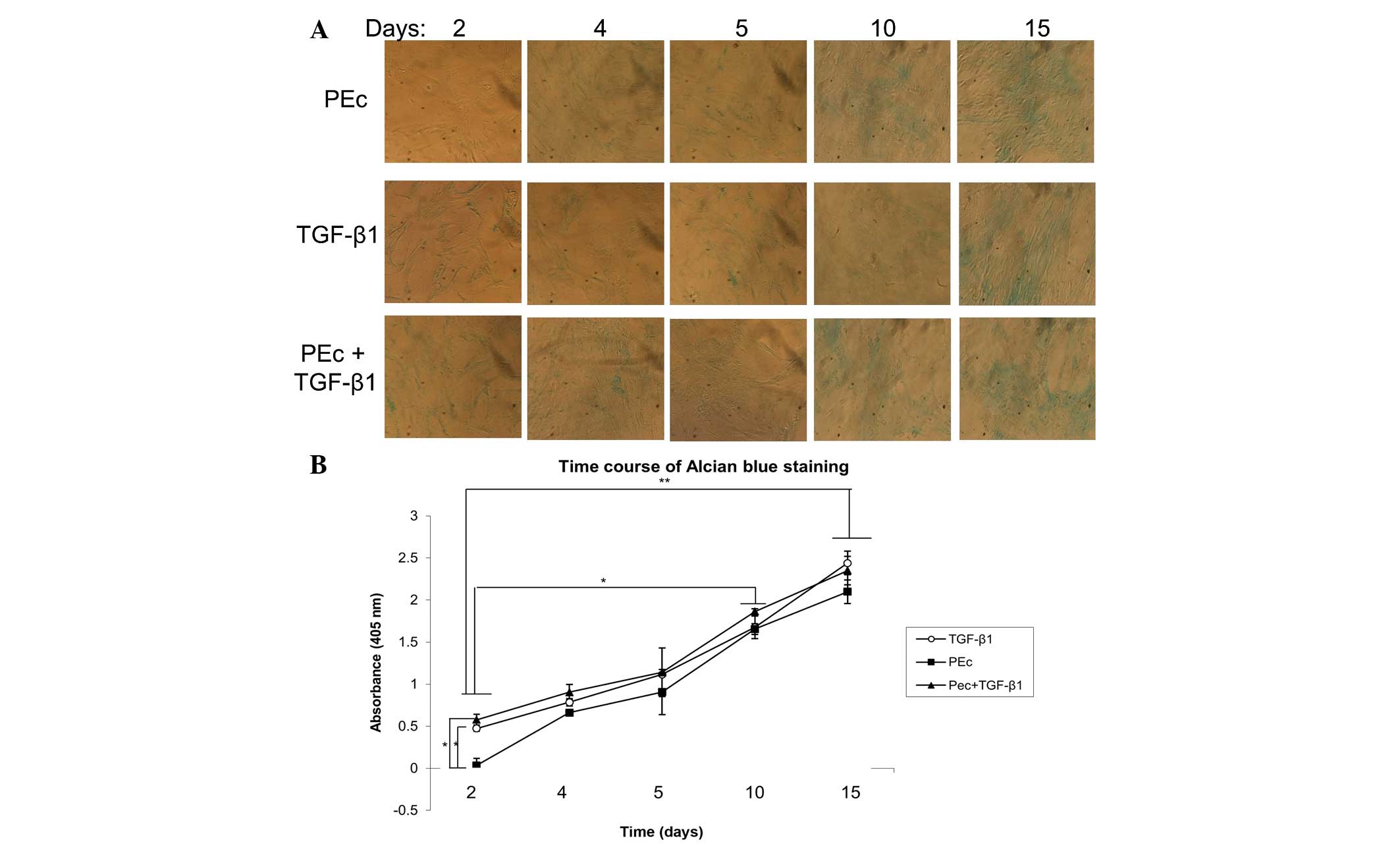

The stimulation of hMSCs towards chondrocytes was

also examined by Alcian blue quantitation, where it was determined

that PEc and PEc+TGF-β1 presented similar levels of Alcian blue

staining to that obtained by TGF-β1 treatment alone, through the

course of the study (15 days) (Fig. 3A

and B). Spontaneous differentiation towards chondrocytes was

examined in untreated hMSCs incubated in tissue culture conditions

for 15 days. No significant transformation was observed of the

untreated hMSC towards chondrocytes by Alcian blue staining after

15 days in tissue culture conditions (results not shown).

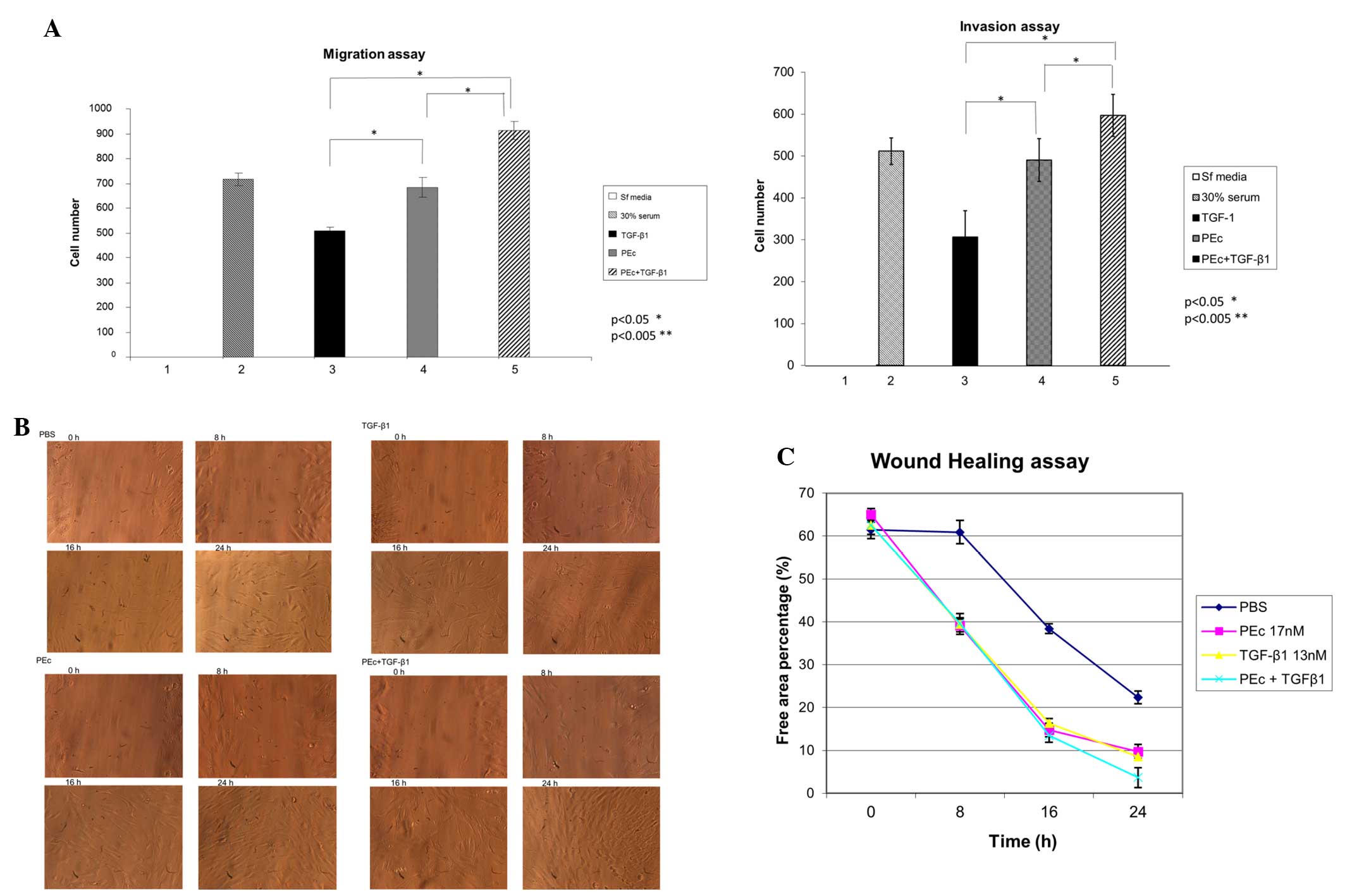

Recent evidence suggests that synthetic PEc can

induce mesenchymal cell mobilization in vitro. Prior to

that, the ability of PEc and of PEc in combination with TGF-β1 to

attract mesenchymal cells, was examined using a migration/invasion

assay. PEc presented a significantly higher rate of mesenchymal

cell migration and invasion capacity compared with TGF-β1

(P<0.05), and the combination of the two factors was associated

with a significantly higher mesenchymal cell migration and invasion

capacity than PEc alone (Fig.

4A).

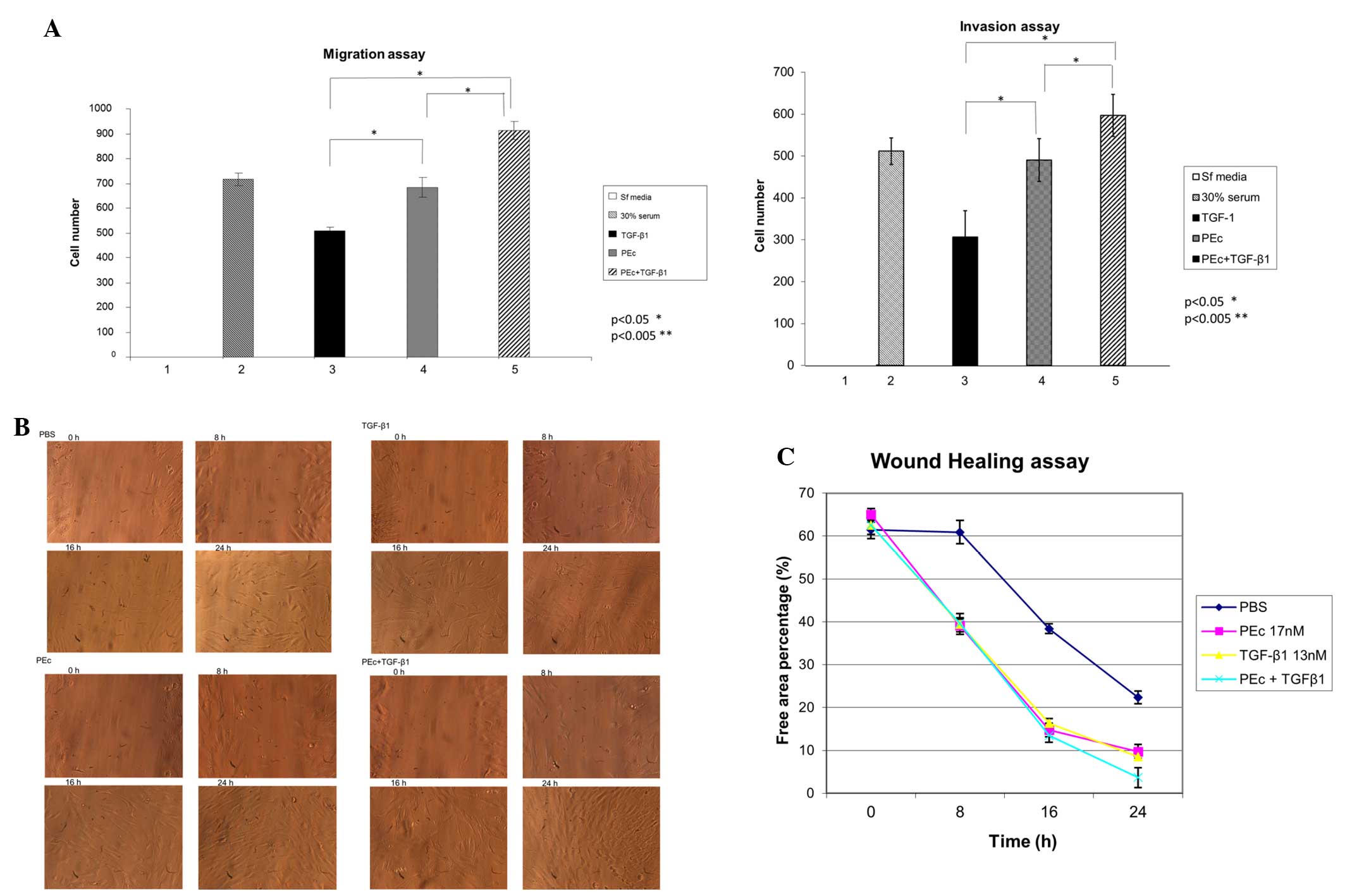

| Figure 4(A) Determination of the effects of

PEc, TGF-β1 and the combination of both, in the hMSC attraction as

assessed by migration/invasion assays (Transwell system) at 24 h.

The top well always contained the hMSCs. PEc and PEc+TGF-β1 were

associated with a significant increase in hMSC migration and

invasion compared with TGF-β1 alone (migration assay PEc vs.

TGF-β1: P=0.04, PEc+TGF-β1: P<0.001; invasion assay, PEc vs. TGF

β1 and PEc vs. PEc+TGF β1: P<0.002). (B) Wound healing assay of

the effects of PEc, TGF-β1 and TGF-β1+PEc on the HMC mobilization.

(C) Quantification of the wound healing assay. The combination

treatment presented a significant increase in migration of hMSCs

compared with the PEc alone (P=0.004). HMC treated with PEc in

combination with TGF-β1 presented a much greater mobilization

activity in 24 h compared to the HMC treated with TGF-β1 alone

(one-way analysis of variance, P=0.008, n=3).

*P<0.05, **P<0.005. PEc, Ec peptide;

TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; hMSCs, human mesenchymal

stem cells. |

To further examine the effect of these factors on

hMSC mobilization, a wound healing assay was conducted. It was

determined that hMSCs treated with PEc+TGF-β1 exhibited a

significantly elevated migration level at 24 h compared with TGF-β1

or PEc alone, similar to that obtained by PEc treatment (Fig. 4B and C).

Discussion

MSCs are able to differentiate into osteoblasts,

chondrocytes, and adipocytes and expand to numbers relevant for

clinical application. Growth factors are essential in the

chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs. Previous studies have

demonstrated that supplementation of TGF-β1 initiated and improved

chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs in a time- and dose-dependent

manner (35).

In this study, the effects of PEc (the last 24 aa of

the COO− terminal of the IGF-1Ec isoform, not included

in the mature IGF-1) on human mesenchymal cell differentiation and

migration, alone and in combination with TGF-β1 were examined.

Recent evidence suggests that PEc attracts mesenchymal cells prior

to the repair of myocardial cells and of muscle cells (26–28),

whereas it was also found to inhibit HMSC osteogenic

differentiation and induce differentiation towards adipocytes

(28). TGF-β1 is a known factior

to cause HMSC cells to differentiate towards chondrocytes that has

been introduced in clinical practise (12). The aim of the present study was to

examine the possibility of using a combination of these factors in

clinical practice. It was observed that PEc activates ERK 1/2 in a

similar manner to TGF-β1. Since TGF-β1 induces mesenchymal

differentiation through ERK 1/2 activation, the effect of PEc on

mesenchymal cell differentiation was examined. The results obtained

suggest that PEc, apart from inducing mesenchymal cell

mobilization, interestingly and in contrast to a previous study

(28), can also induce the

differentiation towards chondrocytes, similar to TGF-β1. The

combination of both factors exhibited a greater effect as shown by

significantly higher production of Col II and decreased production

of Col I compared with the treatment with the two factors

separately, whilst Col X was unaffected.

The effect of PEc, TGF-β1, and the combination of

both on the migration and invasion capacities of hMSCs was also

investigated. PEc induced hMSC migration and invasion capacities

more than TGF-β1, whereas the combination of both factors was

associated with a significant increase of the hMSC migration and

invasion ability compared with PEc alone. The results from the

wound healing assay were similar as it was determined that the

combination of these two factors was associated with increased

mesenchymal cell mobilization compared with TGF-β1 alone and was

similar to that induced by PEc.

These results suggest that the two factors do not

negatively interfere with each other in respect to their effect on

the differentiation and migration capacity of hMSCs into

chondrocytes. The combination of these factors appears to have a

synergistic effect in causing hMSC differentiation towards

chondrocytes. Furthermore, the ability of PEc to attract hMSCs is

not diminished when it is combined with TGF-β1.

Further studies in in vivo models are

required in order to better assess the effects of the introduction

of PEc and of PEc together with TGF-β1 on cartilage formation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National and

Kapodistrian University of Athens, as well as the Department of

Physiology, Athens Medical School, Greece.

References

|

1

|

Clegg TE, Caborn D and Mauffrey C:

Viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid in the treatment for

cartilage lesions: A review of current evidence and future

directions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 23:119–124. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Nicolini AP, Carvalho RT, Dragone B, Lenza

M, Cohen M and Ferretti M: Updates in biological therapies for knee

injuries: Full thickness cartilage defect. Curr Rev Musculoskelet

Med. 7:256–262. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sofat N and Kuttapitiya A: Future

directions for the management of pain in osteoarthritis. Int J Clin

Rheumtol. 9:197–276. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Safran MR and Seiber K: The evidence for

surgical repair of articular cartilage in the knee. J Am Acad

Orthop Surg. 18:259–266. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Correa WE and

Pitanguy I: Tissue engineering and auricular reconstruction: A

review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 62:447–452. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Huckle J, Dootson G, Medcalf N, McTaggart

S, Wright E, Carter A, Schreiber R, Kirby B, Dunkelman N, Stevenson

S, et al: Differentiated chondrocytes for cartilage tissue

engineering. Novartis Found Symp. 249:103–112; discussion 112–117,

170–174, 239–241. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Baghaban Eslaminejad M and Malakooty Poor

E: Mesenchymal stem cells as a potent cell source for articular

cartilage regeneration. World J Stem Cells. 6:344–354. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Florine EM, Miller RE, Porter RM, Evans

CH, Kurz B and Grodzinsky AJ: Effects of dexamethasone on

mesenchymal stromal cell chondrogenesis and aggrecanase activity:

Comparison of agarose and self-assembling peptide scaffolds.

Cartilage. 4:63–74. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Haleem-Smith H, Calderon R, Song Y, Tuan

RS and Chen FH: Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein enhances matrix

assembly during chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. J

Cell Biochem. 113:1245–1252. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

10

|

Seo S and Na K: Mesenchymal stem

cell-based tissue engineering for chondrogenesis. J Biomed

Biotechnol. 2011:8068912011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bhardwaj N and Kundu SC: Chondrogenic

differentiation of rat MSCs on porous scaffolds of silk

fibroin/chitosan blends. Biomaterials. 33:2848–2857. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Re'em T, Kaminer-Israeli Y, Ruvinov E and

Cohen S: Chondrogenesis of hMSC in affinity-bound TGF-beta

scaffolds. Biomaterials. 33:751–761. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Chen CC, Liao CH, Wang YH, Hsu YM, Huang

SH, Chang CH and Fang HW: Cartilage fragments from osteoarthritic

knee promote chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells without

exogenous growth factor induction. J Orthop Res. 30:393–400. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lee JI, Sato M, Kim HW and Mochida J:

Transplantatation of scaffold-free spheroids composed of

synovium-derived cells and chondrocytes for the treatment of

cartilage defects of the knee. Eur Cell Mater. 22:275–290;

discussion 290. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nakamura T, Sekiya I, Muneta T, Hatsushika

D, Horie M, Tsuji K, Kawarasaki T, Watanabe A, Hishikawa S,

Fujimoto Y, et al: Arthroscopic, histological and MRI analyses of

cartilage repair after a minimally invasive method of

transplantation of allogeneic synovial mesenchymal stromal cells

into cartilage defects in pigs. Cytotherapy. 14:327–338. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sato M, Uchida K, Nakajima H, Miyazaki T,

Guerrero AR, Watanabe S, Roberts S and Baba H: Direct

transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells into the knee joints of

Hartley strain guinea pigs with spontaneous osteoarthritis.

Arthritis Res Ther. 14:R312012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vanlauwe J, Huylebroek J, Van Der Bauwhede

J, Saris D, Veeckman G, Bobic V, Victor J, Almqvist KF, Verdonk P,

Fortems Y, et al: Clinical outcomes of characterized chondrocyte

implantation. Cartilage. 3:173–180. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tuli R, Tuli S, Nandi S, Huang X, Manner

PA, Hozack WJ, Danielson KG, Hall DJ and Tuan RS: Transforming

growth factor-beta-mediated chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal

progenitor cells involves N-cadherin and mitogen-activated protein

kinase and Wnt signaling cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 278:41227–41236.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li J, Zhao Z, Liu J, Huang N, Long D, Wang

J, Li X and Liu Y: MEK/ERK and p38 MAPK regulate chondrogenesis of

rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through delicate interaction

with TGF-beta1/Smads pathway. Cell Prolif. 43:333–343. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zaslav K, McAdams T, Scopp J, Theosadakis

J, Mahajan V and Gobbi A: New frontiers for cartilage repair and

protection. Cartilage. 3(Suppl 1): S77–S86. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Achar RA, Silva TC, Achar E, Martines RB

and Machado JL: Use of insulin-like growth factor in the healing of

open wounds in diabetic and non-diabetic rats. Acta Cir Bras.

29:125–131. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stavropoulou A, Halapas A, Sourla A,

Philippou A, Papageorgiou E, Papalois A and Koutsilieris M: IGF-1

expression in infarcted myocardium and MGF E peptide actions in rat

cardiomyocytes in vitro. Mol Med. 15:127–135. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Armakolas A, Philippou A, Panteleakou Z,

Nezos A, Sourla A, Petraki C and Koutsilieris M: Preferential

expression of IGF-1Ec (MGF) transcript in cancerous tissues of

human prostate: Evidence for a novel and autonomous growth factor

activity of MGF E peptide in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate.

70:1233–1242. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Philippou A, Armakolas A, Panteleakou Z,

Pissimissis N, Nezos A, Theos A, Kaparelou M, Armakolas N,

Pneumaticos SG and Koutsilieris M: IGF1Ec expression in MG-63 human

osteoblast-like osteosarcoma cells. Anticancer Res. 31:4259–4265.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Milingos DS, Philippou A, Armakolas A,

Papageorgiou E, Sourla A, Protopapas A, Liapi A, Antsaklis A,

Mastrominas M and Koutsilieris M: Insulinlike growth factor-1Ec

(MGF) expression in eutopic and ectopic endometrium:

Characterization of the MGF E-peptide actions in vitro. Mol Med.

17:21–28. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

26

|

Wu J, Wu K, Lin F, Luo Q, Yang L, Shi Y,

Song G and Sung KL: Mechano-growth factor induces migration of rat

mesenchymal stem cells by altering its mechanical properties and

activating ERK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 441:202–207.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hill M, Wernig A and Goldspink G: Muscle

satellite (stem) cell activation during local tissue injury and

repair. J Anat. 203:89–99. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cui H, Yi Q, Feng J, Yang L and Tang L:

Mechano growth factor E peptide regulates migration and

differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol

Endocrinol. 52:111–120. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Armakolas A, Kaparelou M, Dimakakos A,

Papageorgiou E, Armakolas N, Antonopoulos A, Petraki C, Lekarakou

M, Lelovas P, Stathaki M, et al: Oncogenic role of the Ec peptide

of the IGF-1Ec isoform in prostate cancer. Mol Med. 21:167–179.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Matheny RW Jr, Nindl BC and Adamo ML:

Minireview: Mechano-growth factor: A putative product of IGF-I gene

expression involved in tissue repair and regeneration.

Endocrinology. 151:865–875. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Soleimani M and Nadri S: A protocol for

isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse bone

marrow. Nat Protoc. 4:102–106. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)). Method Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lunstrum GP, Keene DR, Weksler NB, Cho YJ,

Cornwall M and Horton WA: Chondrocyte differentiation in a rat

mesenchymal cell line. J Histochem Cytochem. 47:1–6. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Pelttari K, Steck E and Richter W: The use

of mesenchymal stem cells for chondrogenesis. Injury. 39(Suppl 1):

S58–S65. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Pei M, He F and Vunjak-Novakovic G:

Synovium-derived stem cell-based chondrogenesis. Differentiation.

76:1044–1056. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|