Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most frequently

diagnosed cancer in males worldwide, and is the most frequently

diagnosed cancer among males in more developed countries (1). Despite improvements in the clinical

management and treatment of prostate cancer, the five-year relative

survival rate for patients with advanced prostate cancer is ~30%.

It is estimated that 220,800 men in the USA developed prostate

cancer during 2015, and 27,540 men (12.5%) were predicted to

succumb to this malignancy (2).

Novel therapies are required for the effective treatment of

prostate cancer, and biomarkers based on the molecular biology of

the disease are required for early diagnoses.

Aberrant expression or localization of β-catenin has

been frequently observed in prostate tumor cells (3), thus suggesting that activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway may be involved in the development

of prostate cancer. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway regulates cell fate

during embryonic development, and its activation is involved in the

development of cancer (4–7). In the absence of Wnt signaling,

cytoplasmic β-catenin levels are reduced due to destruction

complex-induced degradation. The destruction complex consists of

axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), glycogen synthase kinase 3β

(GSK3β) and casein kinase 1. Alterations that interfere with

β-catenin degradation lead to the accumulation of β-catenin in the

cytoplasm and subsequent translocation to the nucleus. In

conjunction with the T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancing factor

transcription factors, β-catenin then induces cellular responses

through the transcriptional activation of target genes.

Despite previous reports demonstrating that the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway is activated in prostate cancer (3), mutations in APC, β-catenin

(CTNNB1) and axin 1 (AXIN1), are rarely detected (The

Cancer Genome Atlas Network; http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Therefore, additional

mechanisms may be responsible for the upregulation of β-catenin in

prostate cancer. Frequently rearranged in advanced T-cell

lymphomas-1 (FRAT1) overexpression activates the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway by binding to GSK3β. Expression of FRAT1 is elevated in

several types of human cancer, including ovarian cancer (8), esophageal cancer (9), glioma (10–12),

astrocytoma (13), lung (14,15)

and pancreatic cancer (16). A

recent report demonstrated that N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1

regulates β-catenin phosphorylation and nuclear trans-location

through FRAT1 in prostate cancer cells (17), which indicates a potential

association between FRAT1 and aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling in

prostate cancer. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to

investigate the role of FRAT1 in prostate cancer.

Materials and methods

Prostate tissue microarray

A prostate tissue microarray (reference no.

HProA100PG01), consisting of three normal prostate tissue samples

and 59 prostate adenocarcinoma tissue samples, was obtained from

Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Cell culture, plasmid construction and

transfection

The PC-3 and DU-145 human prostate cancer cell

lines, and the NIH3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line were

obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA,

USA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA),

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), penicillin (50 U/ml) and streptomycin (50

μg/ml). Cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator

at 37°C and 5% CO2. Culture medium was refreshed every 3

days and cells were subcultured when confluent.

The FRAT 1 overexpression plasmid (HA-FRAT1/pCEFL),

FRAT1 short hairpin (sh) RNA knockdown plasmid

(pSilencer-FRAT1), and control shRNA plasmid

(pSilencer-control) were generated as described previously

(9). TCF reporter plasmids,

TOPFLASH and FOPFLASH were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology,

Inc. (Lake Placid, NY, USA), and the pRL-TK wild-type control

vector was purchased from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI,

USA).

Transfections were performed in 24-well or 6-well

plates. DU-145 or PC-3 cells (2×105) were seeded into

each well of a 6-well tissue culture plate and were incubated for

24 h. When the cells were 70–80% confluent, the culture media was

removed and cells were washed with pre-warmed sterile

phosphate-buffered saline. Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to transfect

cells with the plasmids according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cells were collected 24 h post-transfection and western blot

analysis and reporter assays were performed. To establish stable

HA-FRAT1/pCEFL or pCEFL empty vector control cell lines,

post-transfection, the medium was supplemented with 400

μg/ml G418 and resistant clones were pooled and maintained

in culture. Exogenous hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged FRAT1 expression

was confirmed by western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from cultured cells

using urea buffer (8 M urea, 1 M thiourea, 0.5% CHAPS, 50 mM

dithiothreitol and 24 mM spermine). The protein concentration was

determined using the Bradford Protein Assay Dye Reagent (cat. no.

500-0006; Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The

samples (40 μg of protein) were then separated by 12% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and were

transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked

with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 at room

temperature for 1 h, and then incubated with primary antibodies

overnight at 4°C. The membranes were subsequently incubated for 1 h

at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated

secondary antibodies. Signals were detected using an enhanced

chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences,

Chalfont, UK) and evaluated using ImageJ software (version, 1.42q;

National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (18). The following primary antibodies

were used: Anti-HA (cat. no. sc-805; dilution, 1:1,000; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), anti-FRAT1 (cat. no.

ab108405; dilution, 1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-β-catenin

(cat. no. 610153; 1:2,000; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ,

USA), anti- phosphorylated (p)- β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41; cat. no.

9561; dilution, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers

MA, USA), anti-β-actin (cat. no. A3854; dilution, 1:5,000;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and

anti-β-tubulin (cat. no. ab6046; dilution, 1:5,000, Abcam, MA,

USA). The following HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used:

Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) H&L (cat. no. ab97051;

dilution, 1:1,000; Abcam), goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (cat. no.

ab6789; dilution, 1:1,000; Abcam).

Cell growth assay

Cells that were stably or transiently transfected

were harvested and re-plated in triplicate in 24-well plates. Cells

were counted every 2 days with a hemocytometer, and a Trypan blue

exclusion assay was used to assess cell viability. In brief, 0.1 ml

Trypan blue stock solution was mixed with 0.1 ml cell suspension

before loading onto a hemocytometer. Cells were counted immediately

under a light microscope at low magnification.

Immunohistochemical analysis

The prostate tissue micro-array was deparaffinized,

rehydrated and incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to

block endogenous peroxidase activity. The slide was subsequently

blocked with normal goat serum at room temperature for 1 h, and

then incubated at 4°C overnight with a primary antibody against

FRAT1 (cat. no. ab137391; dilution, 1:400; Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

The slide was then incubated with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit

IgG H&L secondary antibody (dilution, 1:250; cat. no. BP-9100,

Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) for 40 min at room

temperature, and subsequently stained with the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC

HRP kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) followed by counterstaining

with hematoxylin. The localization of FRAT1 in each sample spot

within the tissue microarray slide was categorized as membranous,

cytoplasmic or nuclear. The staining intensity was graded as

follows: No staining (0), weak (1), moderate (2) and intense staining (3). Samples that could not be graded were

scored as 'not applicable'. For each sample, FRAT1 expression was

determined as the average score of the sample spot, and then

further subgrouped into low (score 0) or high (scores 1–3) FRAT1

expression.

Reporter assays

Following transfection with either TOPFLASH (100 ng)

or FOPFLASH (100 ng), the internal control plasmid pRL-TK (5 ng)

and HA-FRAT1/pCEFL, pCEFL, pSilencer-FRAT1 or

pSilencer-control-transfected cells were cultured for 36 h

at 37°C before they were lysed using Passive Lysis Buffer (cat. no.

E1941; Promega Corporation) to measure the luciferase reporter

activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega

Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Firefly

luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase

activity. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD)

for independent triplicate cultures.

Tumor growth in nude mice

NIH3T3/control or NIH3T3/FRAT1 (4×106)

cells were prepared in 0.2 ml saline, and were injected bilaterally

and subcutaneously, each into the left and right forelegs of four

female nude mice (age, 4–6 weeks; weight, 16–20 g; Beijing HFK

Bioscience Co., Ltd.). Prior to tumor cell implantation, mice were

allowed to acclimatize to laboratory conditions for 3 days. The

mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment and monitored every

2 days. Animals had free access to standard food and water, and

were maintained in 12 h light/dark cycles throughout the course of

treatment. At the end of the experiment, the mice were sacrificed

by cervical dislocation. The date when a palpable tumor first arose

and the weight of the removed tumor were recorded. The mice were

treated in accordance with the Regulations of Laboratory Animal

Quality issued by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology

(Beijing, China). Animal experiments were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cancer Hospital,

Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (reference no.

NCC2015A019).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. A two-tailed,

unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare independent samples

from two groups. Data were analyzed using the SPSS software program

(version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

FRAT1 is expressed exclusively in the

nuclei of normal prostate basal cells and is overexpressed in human

prostate cancer

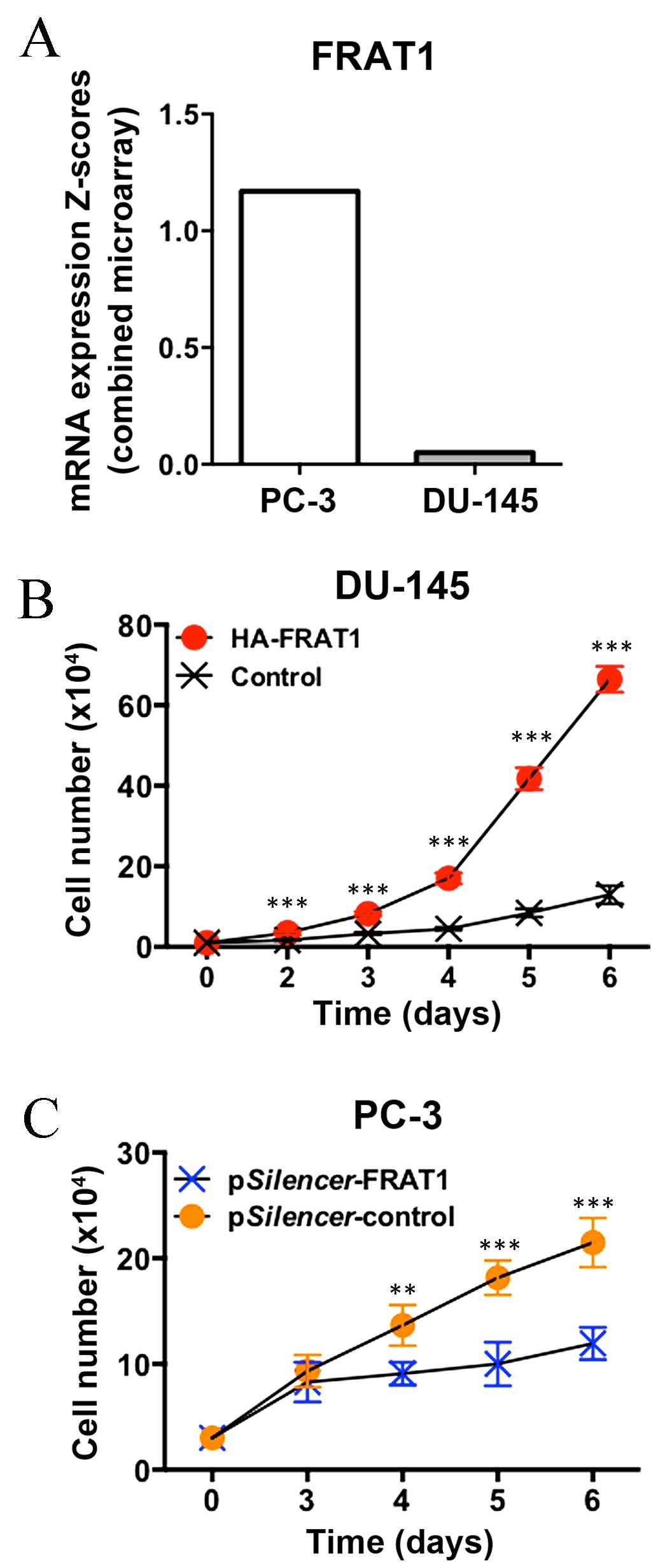

FRAT1 mRNA expression in established human

cell lines was first investigated using the Human Protein Atlas

database (http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000165879-FRAT1/cell).

Notably, FRAT1 mRNA expression levels in PC-3 prostate

cancer cells were observed to be among the highest across all of

the cell lines included in the analysis (Fig. 1A).

In order to explore the clinical implications of

FRAT1 expression in prostate cancer, data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas cBioPortal database (http://www.cbioportal.org/) were analyzed (19–21).

As shown in Fig. 1B, upregulation

of FRAT1 mRNA expression levels was frequent in patients

with prostate adenocarcinoma (41/216, 19%; Memorial Sloan Kettering

Cancer Center; http://www.cbioportal.org/study?id=prad_mskcc#summary).

The protein expression of FRAT1 in normal human

prostate tissue and prostate adenocarcinoma tissues was analyzed by

immunohistochemical analysis using a human prostate cancer tissue

microarray. Expression of FRAT1 was observed in all three cases of

normal prostate epithelium, exclusively in the nuclei of basal

cells (Fig. 2A). These results are

consistent with the in situ hybridization results of a

previous study, demonstrating that FRAT1 protein expression was

present in all samples of normal esophageal squamous cell

epithelium and in the basal layers (9). In the present study, nuclear FRAT1

expression was detected in 68% (40/59) of prostate adenocarcinoma

samples (Fig. 2B). Since only a

small fraction of cells (basal cells) in the normal prostate tissue

samples were observed to express FRAT1, this protein was determined

to be overexpressed in prostate adenocarcinoma tissues.

FRAT1 expression status affects prostate

cancer cell growth

The next aim of the present study was to investigate

whether the expression status of FRAT1 influences the growth of

human prostate cancer cell lines. As determined using the Catalogue

of Somatic Mutations in Cancer database (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), FRAT1 mRNA

expression levels in PC-3 cells were markedly higher when compared

with DU-145 cells (Fig. 3A).

Forced overexpression of FRAT1 markedly promoted the

growth rate of DU-145 cells, with a 4-fold increase observed at day

6 (P<0.001; Fig. 3B).

Conversely, knockdown of FRAT1 expression by RNA interference

(RNAi) significantly inhibited the cell growth rate of PC-3 cells,

with a 30–50% decrease at days 4–6 (P=0.003 at day 4; P<0.001 at

days 5 and 6; Fig. 3C). These data

indicate that increased FRAT1 expression may provide a growth

advantage in prostate cancer cells.

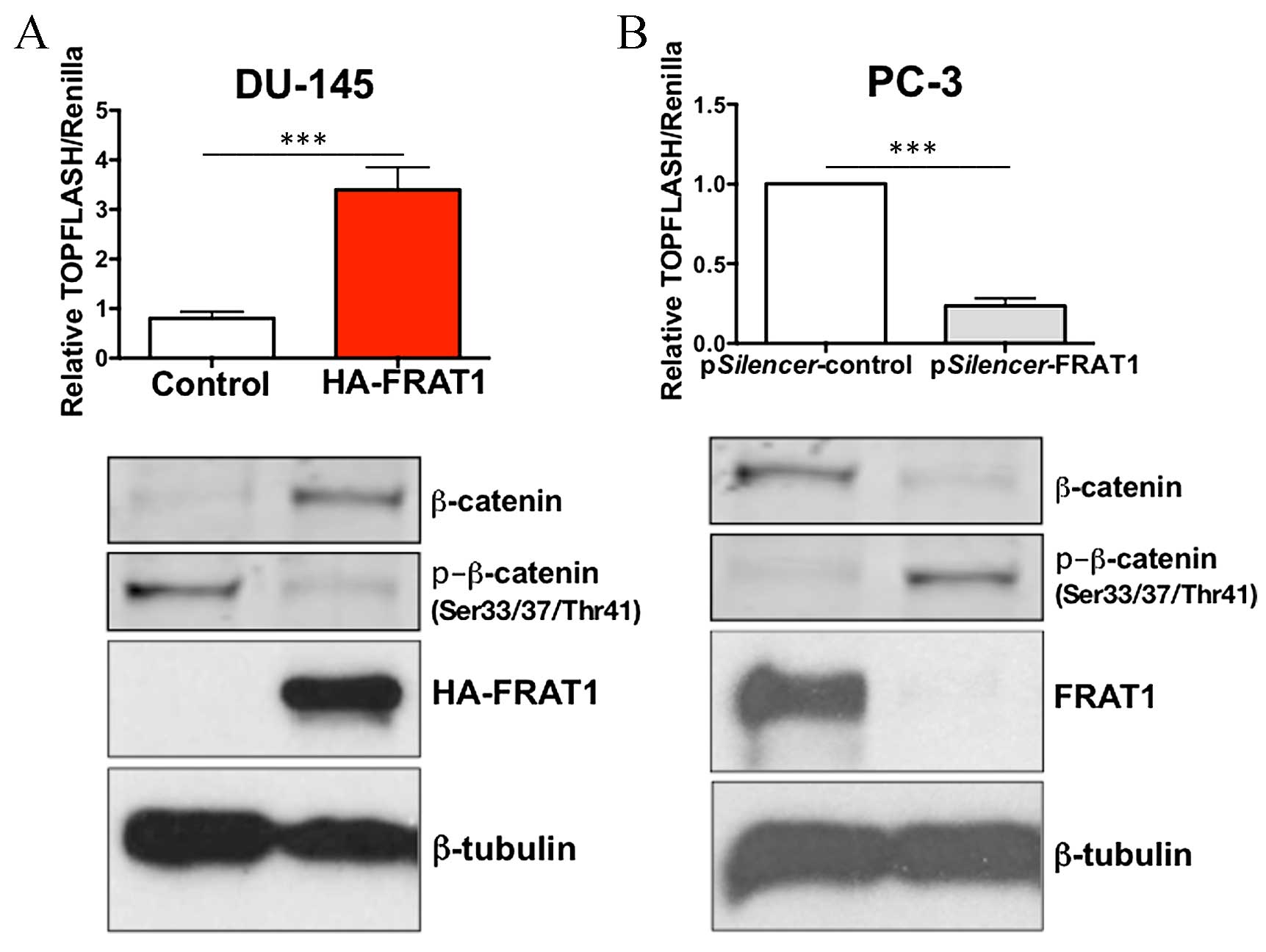

FRAT1 activates β-catenin-dependent

transcriptional activity

It has previously been reported that FRAT1

positively regulates the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway (17). In order to

investigate whether this process may also occur in prostate cancer

cells, the effect of FRAT1 expression on the transcriptional

activity of β-catenin was investigated using a TOPFLASH/FOPFLASH

reporter assay. This assay consists of wild type (TOP) or mutated

(FOP) binding sites for the β-catenin/TCF complex upstream of a

minimal thymidine kinase promoter and luciferase open reading

frame.

Overexpression of FRAT1 in DU-145 cells

significantly increased TOPFLASH activity, with a 3-fold increase

compared to the control cells (P<0.001; Fig. 4A). A minimal effect of FRAT1

overexpression on the FOPFLASH reporter was detected (data not

shown). In addition, knockdown of FRAT1 in PC-3 cells using RNAi,

markedly inhibited β-catenin/TCF-dependent transcriptional

activity, with a >70% reduction in TOPFLASH activity

(P<0.001; Fig. 4B).

Overexpression of FRAT1 in DU-145 cells inhibited

the expression of β-catenin phosphorylated at Ser33/37 and Thr41

residues, which provides an explanation for the observed increase

in total β-catenin levels (Fig.

4A). Conversely, depletion of FRAT1 in PC-3 cells resulted in

an increase in the protein expression levels of p-β-catenin (at

Ser33/37 and Thr41 residues), and decreased levels of total

β-catenin expression (Fig. 4B).

These data confirm that FRAT1 may function to stabilize β-catenin

in prostate cancer cells.

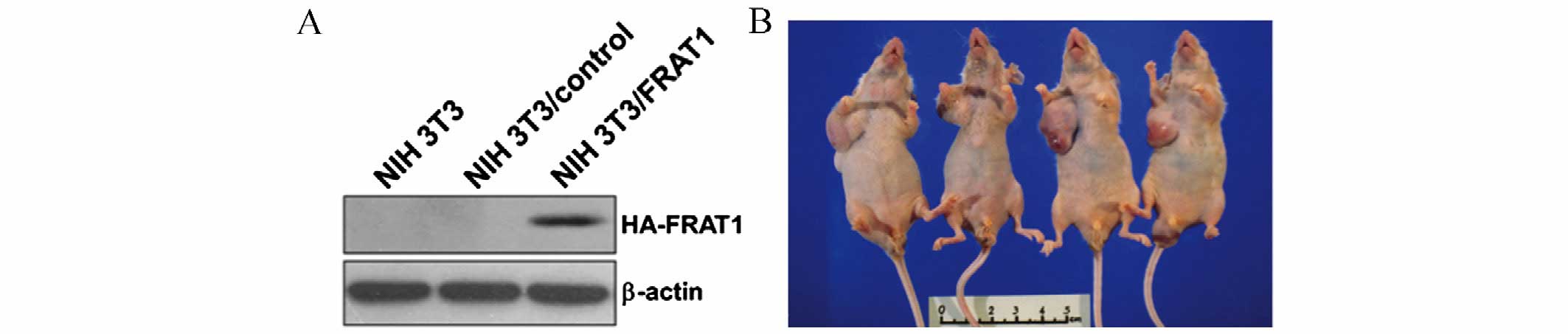

FRAT1 overexpression in NIH3T3 cells

induces tumor formation in nude mice

The in vitro results indicated that FRAT1 may

affect prostate cancer cell growth. In order to confirm the

tumorigenic potential of FRAT1 in vivo, tumor xenograft

experiments involving four nude mice were performed using NIH3T3

cells stably transfected with FRAT1 (NIH3T3/FRAT1) or control

vectors (NIH3T3/control; Fig. 5A).

At 8 weeks following injection with the transfected cells, the mice

were sacrificed and the tumors were removed and weighed. Tumors

developed in all four nude mice at the right lateral site where the

NIH3T3/FRAT1 cells were injected (Fig.

5B and Table I). Conversely,

no palpable tumors developed on the left lateral side where

NIH3T3/control cells were injected (Fig. 5B and Table I). At 3 weeks following injection

with NIH3T3/FRAT1, palpable nodular neoplasms developed and tumors

were observed at week 5. These data provide evidence to suggest

that FRAT1 serves a tumorigenic role in vivo, as its

overexpression in normal NIH3T3 mouse fibroblast cells led to the

formation of tumors in nude mice.

| Table IFRAT1 overexpression in NIH3T3 cells

induces tumor formation in nude mice. |

Table I

FRAT1 overexpression in NIH3T3 cells

induces tumor formation in nude mice.

| No. of

cellsa | NIH3T3/FRAT1

| NIH3T3/control

|

|---|

Tumor

weight

(mg) | No.

tumors/injection | Latencyb

(days) | Tumor

weight

(mg) | No.

tumors/injection | Latencyb

(day) |

|---|

|

4×106 | 2105±409 | 4/4 | 21–35 | 0 | 0/4 | >56 |

Discussion

Prostate cancer is the fifth most common cause of

cancer-associated mortality worldwide in men, and is the eighth

most common cause of cancer-associated mortality overall (1). Molecular biomarkers and personalized

treatment strategies based on an improved understanding of the

molecular mechanisms underlying prostate cancer development and

progression would maximize therapeutic outcome (22). Despite previous reports

demonstrating that a large proportion of prostate tumor cells

exhibit aberrant expression or localization of β-catenin (3), the observation that CTNNB1,

APC and AXIN1 are rarely mutated in prostate cancer

suggests that genetic alterations may not be responsible for

activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (3). The results of the present study

demonstrated that FRAT1 may contribute to the activation of the

β-catenin/TCF pathway in prostate cancer cells, due to the

observation that FRAT1 activated the β-catenin/TCF promoter

luciferase reporter gene in DU-145 prostate cancer cells. In

addition, FRAT1 was observed to affect the growth of prostate

cancer cells in vitro. Furthermore, forced expression of

FRAT1 in NIH3T3 cells was sufficient to induce cell transformation

and lead to tumor growth in vivo. These findings suggested

that FRAT1 exhibits oncogenic properties in prostate cancer.

FRAT1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer. In normal

prostate tissue, FRAT1 is expressed exclusively in the nuclei of

basal cells. At a histological level, the human prostate primarily

consists of epithelial and stromal cells. In the epithelial cell

layer, there are four differentiated cell types, including basal,

secretory luminal, neuroendocrine and transit-amplifying cells.

These cells display distinct morphologies, locations, functions and

expression markers. The basal cells, where adult prostate stem

cells are thought to reside, form a layer of flattened

cuboidal-shaped cells above the basement membrane (23). In 2014, Goksel et al

(24) reported that Wnt

pathway-associated genes, including FRAT1, were

significantly upregulated in the

CD133high/CD44high cancer stem cell (CSC)

monolayer group when compared with non-CSC counterparts. Future

studies will be required to confirm whether FRAT1 is a potential

marker for the stemness of prostate basal cells.

The human FRAT1 gene is a homologue of the

mouse proto-oncogene Frat1, which was demonstrated to convey

a selective advantage to cells at the later stages of murine T-cell

lymphomagenesis (25,26). FRAT1 functions as a GSK3-binding

protein, which is similar to the function of its Xenopus

homolog GSK3-binding protein (27). Ectopic expression of Frat1 in

Xenopus embryos induces secondary axis formation by

stabilizing β-catenin levels (28). Overexpression of Frat1 in

mouse cells induces β-catenin/TCF-dependent reporter gene activity

(29). In addition, Frat1

interacts with Dishevelled (Dvl), which may enable signaling from

Dvl to GSK3 (30). Finally,

low-density lipoprotein receptor related protein 5 recruits axin

and Frat1 to the cell membrane, which induces axin degradation and

Frat1-mediated inhibition of GSK-3. As a consequence, β-catenin is

not targeted for degradation, which leads to the activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (31–33).

In the present study, the nuclear expression

patterns of FRAT1 in normal prostate basal cells and prostate tumor

cells were reported. Although GSK3β generally functions as part of

the β-catenin-degradation complex in the cytosol, there is evidence

to suggest that GSK3β may also reduce Wnt signaling in the nucleus

(34). Caspi et al

(34) demonstrated that GSK3β is

able to translocate to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with

β-catenin and reduces the level of β-catenin/TCF-dependent

transcriptional activity. The results of the present study suggest

that nuclear FRAT1 activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

and confers an increase in prostate cancer cell growth, potentially

by preventing nuclear GSK3β-mediated inhibition of β-catenin/TCF

activity.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Youth Foundation (grant nos. 81201779 and

81502118), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (grant

no. 2014CFB250) and the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (grant nos. 81452761 and 81321091). Dr Yihua Wang was

supported by Biological Sciences, Faculty of Natural and

Environmental Sciences, University of Southampton.

References

|

1

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 65:5–29. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kypta RM and Waxman J: Wnt/beta-catenin

signalling in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 9:418–428. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Clevers H: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in

development and disease. Cell. 127:469–480. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Reya T and Clevers H: Wnt signalling in

stem cells and cancer. Nature. 434:843–850. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Barker N and Clevers H: Mining the Wnt

pathway for cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 5:997–1014.

2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kahn M: Can we safely target the WNT

pathway? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 13:513–532. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang Y, Hewitt SM, Liu S, Zhou X, Zhu H,

Zhou C, Zhang G, Quan L, Bai J and Xu N: Tissue microarray analysis

of human FRAT1 expression and its correlation with the subcellular

localisation of beta-catenin in ovarian tumours. Br J Cancer.

94:686–691. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang Y, Liu S, Zhu H, Zhang W, Zhang G,

Zhou X, Zhou C, Quan L, Bai J, Xue L, et al: FRAT1 overexpression

leads to aberrant activation of beta-catenin/TCF pathway in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 123:561–568.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guo G, Mao X, Wang P, Liu B, Zhang X,

Jiang X, Zhong C, Huo J, Jin J and Zhuo Y: The expression profile

of FRAT1 in human gliomas. Brain Res. 1320:152–158. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Guo G, Kuai D, Cai S, Xue N, Liu Y, Hao J,

Fan Y, Jin J, Mao X, Liu B, et al: Knockdown of FRAT1 expression by

RNA interference inhibits human glioblastoma cell growth, migration

and invasion. PloS One. 8:e612062013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Guo G, Zhong CL, Liu Y, Xue N, Liu Y, Hao

J, Fan Y, Jin J, Mao X and Liu B: Overexpression of FRAT1 is

associated with malignant phenotype and poor prognosis in human

gliomas. Dis Markers. 2015:2897502015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Guo G, Liu B, Zhong C, Zhang X, Mao X,

Wang P, Jiang X, Huo J, Jin J, Liu X and Chen X: FRAT1 expression

and its correlation with pathologic grade, proliferation, and

apoptosis in human astrocytomas. Med Oncol. 28:1–6. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhang Y, Yu JH, Lin XY, Miao Y, Han Y, Fan

CF, Dong XJ, Dai SD and Wang EH: Overexpression of Frat1 correlates

with malignant phenotype and advanced stage in human non-small cell

lung cancer. Virchows Arch. 459:255–263. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang Y, Han Y, Zheng R, Yu JH, Miao Y,

Wang L and Wang EH: Expression of Frat1 correlates with expression

of β-catenin and is associated with a poor clinical outcome in

human SCC and AC. Tumour Biol. 33:1437–1444. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yuan Y, Yang Z, Miao X, Li D, Liu Z and

Zou Q: The clinical significance of FRAT1 and ABCG2 expression in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 36:9961–9968. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jin R, Liu W, Menezes S, Yue F, Zheng M,

Kovacevic Z and Richardson DR: The metastasis suppressor NDRG1

modulates the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of

β-catenin through mechanisms involving FRAT1 and PAK4. J Cell Sci.

127:3116–3130. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Schneider CA, Rasband WS and Eliceiri KW:

NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods.

9:671–675. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H,

Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, Arora VK, Kaushik P, Cerami E, Reva

B, et al: Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer.

Cancer Cell. 18:11–22. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G,

Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al:

Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical

profiles using the cBio-Portal. Sci Signal. 6:pl12013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE,

Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et

al: The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring

multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2:401–404.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chesire DR and Isaacs WB: Beta-catenin

signaling in prostate cancer: An early perspective. Endocr Relat

Cancer. 10:537–560. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Prajapati A and Gupta S, Mistry B and

Gupta S: Prostate stem cells in the development of benign prostate

hyperplasia and prostate cancer: Emerging role and concepts. Biomed

Res Int. 2013:1079542013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Goksel G, Bilir A, Uslu R, Akbulut H,

Guven U and Oktem G: WNT1 gene expression alters in heterogeneous

population of prostate cancer cells; decreased expression pattern

observed in CD133+/CD44+ prostate cancer stem cell spheroids. J

BUON. 19:207–214. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jonkers J, Korswagen HC, Acton D, Breuer M

and Berns A: Activation of a novel proto-oncogene, Frat1,

contributes to progression of mouse T-cell lymphomas. EMBO J.

16:441–450. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jonkers J, Weening JJ, van der Valk M,

Bobeldijk R and Berns A: Overexpression of Frat1 in transgenic mice

leads to glomerulosclerosis and nephrotic syndrome, and provides

direct evidence for the involvement of Frat1 in lymphoma

progression. Oncogene. 18:5982–5990. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yost C, Farr GH III, Pierce SB, Ferkey DM,

Chen MM and Kimelman D: GBP, an inhibitor of GSK-3, is implicated

in Xenopus development and oncogenesis. Cell. 93:1031–1041. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jonkers J, van Amerongen R, van der Valk

M, Robanus-Maandag E, Molenaar M, Destrée O and Berns A: In vivo

analysis of Frat1 deficiency suggests compensatory activity of

Frat3. Mech Dev. 88:183–194. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

van Amerongen R, van der Gulden H, Bleeker

F, Jonkers J and Berns A: Characterization and functional analysis

of the murine Frat2 gene. J Biol Chem. 279:26967–26974. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li L, Yuan H, Weaver CD, Mao J, Farr GH

III, Sussman DJ, Jonkers J, Kimelman D and Wu D: Axin and Frat1

interact with dvl and GSK, bridging Dvl to GSK in Wnt-mediated

regulation of LEF-1. EMBO J. 18:4233–4240. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hay E, Faucheu C, Suc-Royer I, Touitou R,

Stiot V, Vayssière B, Baron R, Roman-Roman S and Rawadi G:

Interaction between LRP5 and Frat1 mediates the activation of the

Wnt canonical pathway. J Biol Chem. 280:13616–13623. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Thomas GM, Frame S, Goedert M, Nathke I,

Polakis P and Cohen P: A GSK3-binding peptide from FRAT1

selectively inhibits the GSK3-catalysed phosphorylation of axin and

beta-catenin. FEBS Lett. 458:247–251. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hagen T, Cross DA, Culbert AA, West A,

Frame S, Morrice N and Reith AD: FRAT1, a substrate-specific

regulator of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity, is a cellular

substrate of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 281:35021–35029. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Caspi M, Zilberberg A, Eldar-Finkelman H

and Rosin-Arbesfeld R: Nuclear GSK-3beta inhibits the canonical Wnt

signalling pathway in a beta-catenin phosphorylation-independent

manner. Oncogene. 27:3546–3555. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|