Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common type of

malignant bone carcinoma, which occurs primarily in the metaphyseal

regions of long bones in adolescents and young adults (1). The 5-year survival rates of patients

with OS without metastases is 60% (2). Although the survival rate has

improved considerably following the introduction of neoadjuvant

chemotherapy, it has reached a plateau and novel biological

therapies are required to achieve further improvement. Although

genetic alterations in OS have been extensively studied,

understanding of the etiology of OS remains limited. Notably,

epigenetics is emerging as an promising strategy for the study of

OS.

DNA methylation, one of the most important

mechanisms involved in microRNA expression regulation (3), gene silencing (4) and alternative gene splicing (5), exerts important functions in the

early stage of carcinoma. As DNA methylation is stable and easily

detected qualitatively or quantitatively, it has been identified to

be a promising diagnostic marker for the early detection of cancer

(6), compared with copy number

variations (7), single nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs)/mutations (8)

and gene/microRNA expression (9).

Previously, numerous instances of abnormal DNA methylation in the

early stage of OS have been identified. For example, previous

studies have indicated that Ras association domain family member

1A, death associated protein kinase, O-6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase, TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 3, and RB

transcriptional corepressor 1 are hypermethylated in OS (10–12).

In addition, Sonaglio et al (13) demonstrated that the

hypermethylation of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A is

associated with the absence of OS metastases, although estrogen

receptor 1 hypermethylation is associated with decreased overall

survival in OS. In addition, hypomethylation of iroquois homeobox 1

has been suggested to promote OS metastasis by inducing C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand 14/nuclear factor-κB signaling (14). Despite the fact that a number of

diagnostic panels have been developed, to the best of our

knowledge, the causes of OS remain to be completely elucidated.

Previously, microarray analysis has been used to

detect genetic alterations and identify potential targets in human

OS cell lines. Kresse et al (15) combined the genetic and epigenetic

profiles of 19 OS samples on the basis of microarray technologies,

and deposited the OS-associated DNA methylation dataset in the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (no. GSE36002). In the previous

study, the differentially methylated genes were extracted and

functional enrichment analysis was implemented. However, the

interactions among the differentially methylated genes were not

measured.

Therefore, in order to better understand the

molecular mechanisms of OS, the present study aimed to extract the

differentially methylated genes from OS and normal samples from

GSE36002. Hierarchical clustering was performed based on Euclidian

distance and average linkage criteria. Functional enrichment

analysis was respectively implemented for differentially

hypomethylated/hypermethylated genes, to further identify the

potential biological processes based on the Database for

Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID).

Subsequently, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was

established to analyze the interactions between differentially

methylated genes, followed by hub gene identification. The results

of the present study provided evidence of the cumulative roles of

epigenetic mechanisms in OS.

Materials and methods

Collection of DNA methylation

data

DNA methylation data for OS (accession no. GSE36002)

(15) was obtained from the GEO in

the National Center for Biotechnology Information database

(www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds), which was

deposited in the GPL8490 platform (Illumina Human Methylation27

BeadChip; Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). GSE36002 included 25

samples (19 OS cell lines, and six normal samples derived from two

osteoblast and four normal bone samples). Specifically, the 19 OS

cell lines were obtained from EuroBoNeT

(eurobonet.pathobiology.eu/cd/index.php). The two normal bone

samples were collected from patients with cancer (one with OS and

one with renal cell cancer) at the Norwegian Radium Hospital (Oslo,

Norway). The normal bone was obtained from a site as distant as

possible from the tumor site. The other two normal bone samples

from different donors were purchased from Capital Biosciences, Inc.

(Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The two human osteoblast cultures

separated from the calvariae of different donors were purchased

from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. (San Diego, CA,

USA).

DNA methylation data quality control

and identification of differentially methylated genes

The methylation-identification algorithm in Genelibs

(www.genelibs.com/gb) was utilized in the

present study. The raw methylation status of 27,578 CpG sites was

downloaded. Probes were eliminated from the dataset when they met

the following criteria: i) Probes with SNP-CpG distances ≤2; ii)

probes on X and Y chromosomes; iii) minimum allelic frequency

<0.05; and iv) cross-hybridizing probes. Subsequently, DNA

methylation data from the 25,628 CpG sites were kept for subsequent

analysis.

The DNA methylation microarray data were processed

using the Lumi package (bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/lumi.html)

(16,17) of Bioconductor software. Data were

normalized via the β-mixture quantile normalization method

(18). Subsequently, β values

(percentage methylation changes) were utilized in graphical

representations of the data and demonstrated the percentage of

methylation counted using the formula methylated/(methylated +

unmethylated), ranging between 0 and 1; 0 represented fully

unmethylated, while 1 represented fully methylated. In the present

study, the β values of the OS and normal groups were calculated.

Subsequently, the absolute value of the difference in mean β values

between OS and normal groups was calculated, termed A. A Student's

t-test was employed in the analysis to identify the differentially

methylated CpGs between the two conditions. Differentially

methylated CpGs were identified based on P<0.05 and A>0.01.

SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for

statistical analysis.

Refinement of the basic differential

methylation analysis

In order to decrease the number of non-variable

sites to enhance the statistical power of the following analyses,

further filtering steps were performed to promote a more stringent

analysis. All sites with β values ≤0.2 and ≥0.8 were deleted from

all 25 samples, in order to decrease the number of non-variable

sites to further promote the statistical power of the subsequent

analyses (19). Additionally, only

CpGs with a mean β-value difference ≥0.2 were kept. The absolute

β-values in each matched pair were examined. A cut-off threshold of

≥0.2 average β-values difference was applied to detect CpGs with

substantial methylation differences.

Hierarchical clustering analysis

Hierarchical clustering is a common approach

utilized to determine clusters of similar data in multidimensional

spaces (20). Generally, cancers

having similar methylation profiles clustered together. To analyze

whether these differentially methylated CpGs could segregate the

samples into two distinct clusters including OS and normal samples,

unsupervised hierarchical clustering was conducted using Euclidian

distance and average linkage criteria (21). The matrix of mean β-value levels of

differential methylated CpGs was formed between OS and normal

samples.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of

differentially methylated genes

GO analysis has been widely utilized for large-scale

functional enrichment research (22). In the present study, GO functional

enrichment analysis was implemented for differentially methylated

genes using DAVID (david.ncifcrf.gov) which is a software tool providing

a comprehensive set of functional annotation for researchers to

understand the biological meaning behind a large number of genes

(23). Specifically, Fisher's

exact test was used to classify the GO category. Subsequently,

P-values were corrected using the false discovery rate (FDR) with

the Benjamini & Hochberg method (24). Functional terms with FDR <0.01

and gene count >10 were considered to be statistically

significant.

Pathway enrichment analysis of

differentially methylated genes

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG;

www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway) is a

knowledge base used to systematically analyze gene functions

(25). In the present study,

pathway analysis was performed according to the KEGG using the

DAVID tool. Fisher's exact test was used to extract the significant

pathways, and the threshold of significance was defined by FDR.

Significant pathways were selected according to the thresholds of

FDR <0.01 and gene count >10.

PPI network construction and hub genes

identification

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting

Genes (STRING) database (www.bork.embl-heidelberg.de/STRING) is a global

resource for analyzing PPI information (26). In the present study, the STRING

tool was used to identify the PPIs of differentially methylated

genes. The differentially methylated genes with required confidence

(combined score) >0.8 were extracted, and the PPI network was

established and displayed using Cytoscape software (cytoscape.org) (27).

Given that the networks were scale-free, the hub genes were

identified with degree >90.

Results

Identification of differentially

methylated genes

Following quality control and normalization to

remove probes with SNP-CpG distance ≤2, on the X and Y chromosomes,

with minimum allelic frequency <0.05, and cross-hybridizing, a

total of 25,628 methylated CpGs remained in the final dataset of 25

samples. A volcano plot exhibiting the distribution of the 25,628

analyzed methylated CpGs was produced, as presented in Fig. 1. Among these 25,628 methylated

CpGs, 5,889 CpGs (representing 4,677 genes) were differentially

methylated, when the absolute value of the mean β-value difference

between the OS and normal groups was >0.01 and the P-value was

<0.05. A total of 572 of the CpGs were hypermethylated and 5,317

CpGs were hypomethylated in the OS group compared with the normal

group.

Subsequently, these 5,889 methylated CpGs initially

extracted as differentially methylated sites were subjected to

further filtering. Using the cut-off threshold of ≥0.2 average

β-values difference, 3,725 unique CpGs (covering 2,862 genes) were

detected to be differentially methylated between the OS and normal

groups. Among these 2,862 genes, 510 gene were differentially

hypermethylated genes and 2,352 were differentially hypomethylated

genes.

Cluster analysis of the differentially

methylated genes

The cluster heat map is presented in Fig. 2. In this figure, it was observed

that there were distinctive methylation patterns in OS and normal

samples, which segregated samples into two distinct groups

comprising those from OS and normal populations.

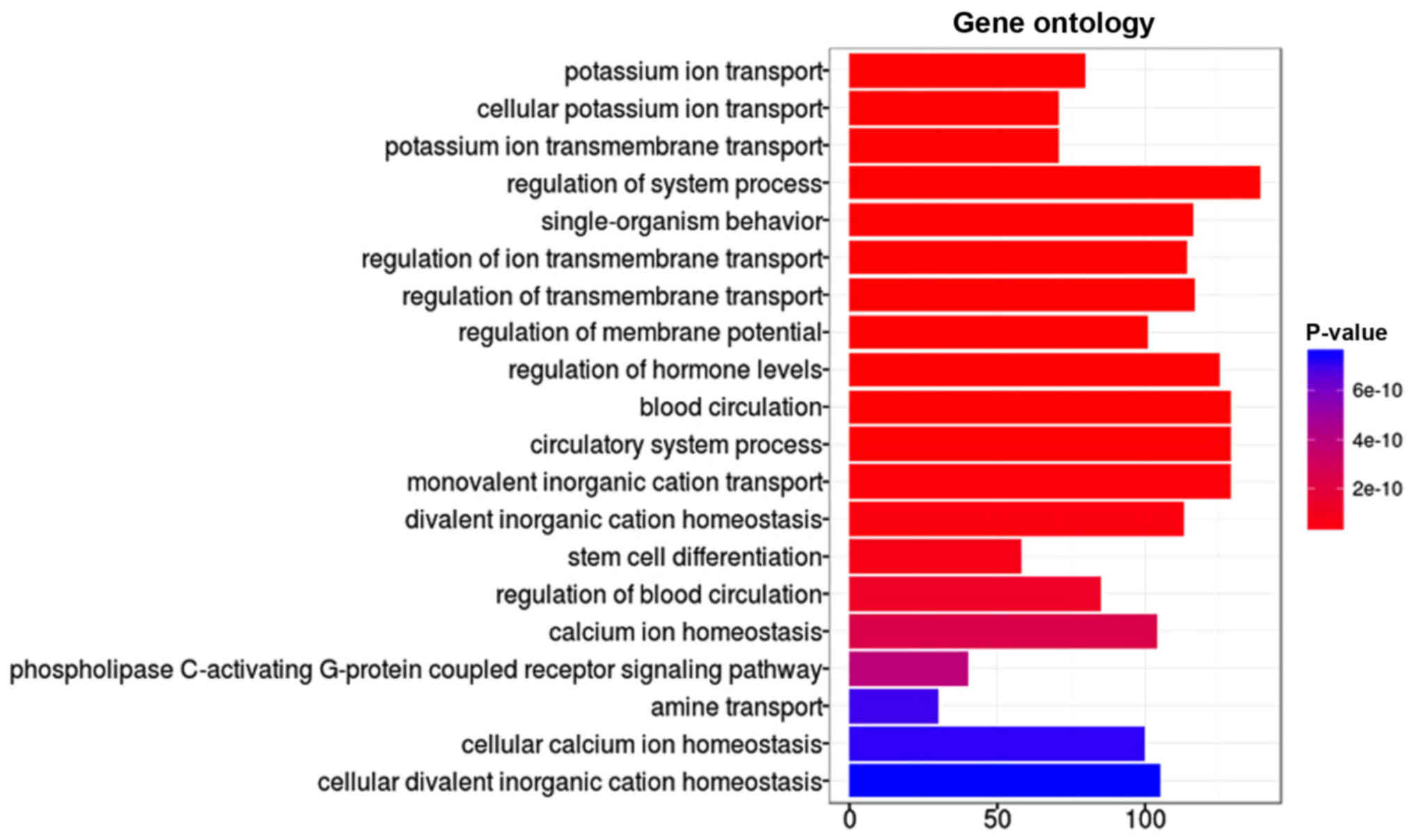

GO enrichment of differentially

methylated genes

In order to better understand the potential

biological functions of the differentially methylated genes, all

the genes were annotated using GO annotation based on DAVID

software. GO categories with FDR <0.01 and gene count >10

were regarded as significantly enriched. Overall, 20 GO terms were

significantly enriched by differentially hypermethylated genes, as

presented in Fig. 3. These GO

terms were sorted in ascending order based on FDR value, and the

top 3 most significantly enriched differentially hypermethylated

genes were associated with potassium ion transport. For

differentially hypomethylated genes, GO functions primarily

included passive transmembrane transporter activity, channel

activity and metal ion transmembrane transporter activity, as

described in Fig. 4.

KEGG pathway analysis for

differentially methylated genes

Pathway enrichment analysis of all differentially

methylated genes was performed based on the KEGG automatic

annotation server. Based on FDR <0.01 and gene count >10, no

KEGG pathways were enriched by the differentially hypermethylated

genes. Notably, differentially hypomethylated genes were enriched

in 10 KEGG pathways, including neuroactive ligand-receptor

interaction (FDR=3.5×10−9; gene count=80), pathway in

cancer (FDR=3.2×10−7; gene count=96) and Rap1 signaling

pathway (FDR=6.5×10−6; gene count=58). The specific

enrichment results are presented in Table I.

| Table I.KEGG pathway analysis for

differentially methylated genes, based on FDR <0.01 and gene

count >10. |

Table I.

KEGG pathway analysis for

differentially methylated genes, based on FDR <0.01 and gene

count >10.

| Terms | Gene count | FDR |

|---|

| Neuroactive

ligand-receptor interaction | 80 |

3.5×10−9 |

| Pathways in

cancer | 96 |

3.2×10−7 |

| Rap1 signaling

pathway | 58 |

6.5×10−6 |

| Calcium signaling

pathway | 58 |

1.9×10−4 |

| Morphine

addiction | 31 |

2.1×10−3 |

| MAPK signaling

pathway | 36 |

2.4×10−3 |

| Cholinergic

synapse | 46 |

3.9×10−3 |

| Circadian

entrainment | 50 |

6.4×10−3 |

| cAMP signaling

pathway | 30 |

6.5×10−3 |

| Cell adhesion

molecules | 27 |

7.1×10−3 |

PPI network construction and hub genes

identification

With the goal of analyzing the association between

differentially methylated genes, STRING software was used to

establish the PPI network. When the differentially methylated genes

with required confidence (combined score) >0.8 were submitted

into STRING, a total of 3,775 PPI interactions (covering 195 nodes)

were obtained, as presented in Fig.

5. The hub genes in the networks with connectivity degree

>90 were identified. A total of 7 hub genes were selected from

the PPI network, which included neuromedin U (NMU; degree=103), NMU

receptor 1 (NMUR1; degree=103), NMUR2 (degree=103), calcium sensing

receptor (degree=103), formyl peptide receptor 2 (degree =92),

melanin concentrating hormone receptor (MCHR) 2 (degree=91) and

MCHR1 (degree=91).

Discussion

The analysis of DNA methylation data has been widely

used to identify abnormally methylated genes associated with OS and

has enabled the extraction of targets for therapeutic strategies.

In the present study, OS pathogenesis was analyzed using

bioinformatics, including the detection of differentially

methylated genes, functional analyses of the differentially

methylated genes, PPI construction, and hub genes identification.

According to the results, the potential mechanisms of OS were

revealed, which provided novel insights into OS diagnosis and

therapy.

Following implementation of the pathway functional

analyses for differentially hypomethylated genes, the pathway of

neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction was selected as the most

significant pathway. Neuroactive steroids act as mediators of

neurotransmitter receptors to regulate neuronal activity (28). The effect of steroids indicates a

ligand-receptor interaction. Previous studies have reported that

neuroactive steroids have been suggested to affect the modulation

of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors (29,30).

Notably, studies have reported that GABA receptors control cell

proliferation and have suggested that there may be an association

between the GABAergic system and oncogenesis (31,32).

In particular, GABA has been observed to be overexpressed in a

number of types of tumors, including gastric, colon, ovarian, and

breast cancer (32–34). At present, the pathway of

neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction has not been demonstrated

to be directly involved in OS. According to the results of the

present study, it may be inferred that neuroactive ligand-receptor

interaction might serve a role in OS, partially by regulating the

expression of GABA.

Notably, the GO results in the present study

indicated that the top 3 functions enriched by differentially

hypermethylated genes were associated with potassium ion transport.

A previous study suggested that ion channels may be involved in the

progression of cancer (35).

Potassium channels, a class of ion channel, have been demonstrated

to be aberrantly expressed in tumor cells and to be involved in

carcinogenesis (36,37). Potassium channels serve diverse

roles in cancer-associated processes, including cell survival,

proliferation, and migration (38,39).

Notably, a previous study demonstrated the roles of potassium

channels in the control of glioma cell survival, growth and

migration (40). Potassium

chloride cotransporter 2 has been indicated to increase cervical

cancer cell invasion through an ion transport-based mechanism

(41). A high level of potassium

expression has been reported in OS (42,43).

Accordingly, the results of the present study indicated a further

link between potassium ion transport and OS progression.

For differentially hypomethylated genes, GO

functions were associated with transmembrane transporter activity.

Facilitated glucose transporters regulate the energy-associated

transport of glucose across the plasma membrane (44). A previous study demonstrated that

the suppression of glucose transport was associated with apoptosis

(45). Apoptosis has been

implicated to exert an important role in the progression of OS.

Increasing evidence has suggested that the induction of apoptosis

may be an effective means of inhibiting tumor formation and

development (46–48). As reported, one cellular mechanism

which produces resistance to antineoplastic therapy involves the

efflux of drugs from cancer cells through specific transmembrane

transporters (49). Therefore, it

may be inferred that transmembrane transporter activity is

associated with OS progression.

Based on the degree distribution in the PPI network,

NMU and NMUR1 exhibited the highest degrees. NMU, a neuropeptide,

has potent activity in energy homeostasis (50). A previous study demonstrated that

NMU may cause the release of inflammatory cytokines from T cells or

macrophages (51). Notably,

cytokine-releasing immune cells may stimulate neovascularization to

promote the growth of human neoplasms. Studies have indicated that

NMU is associated with tumorigenesis. For example, NMU has been

reported to stimulate the migration of renal cancer cells (52,53),

and acts as a potential growth factor for myeloid leukemia

(54). NMUR1, a receptor of NMU,

has been demonstrated to be expressed in renal cancer cells

(52). The potential role of NMU

and NMUR1 in OS has not been documented. According to the results

of the present study, it may be inferred that NMU and NMUR1 may

serve an important role in OS.

In the present study, the data were recruited from

the DNA methylation dataset GSE36002, which was analyzed by Kresse

et al (15). Consistent

with the study of Kresse et al, differentially methylated

genes between OS and normal samples were extracted in the present

study, and GO functional and pathway enrichment analyses were

implemented to examine the underlying mechanism of OS. However,

there remain certain discrepancies. On the basis of the study of

Kresse et al, further analyses using bioinformatics were

performed in the present study, including the construction of the

PPI network and hub gene analysis.

However, the present study had certain limitations.

There was a small amount of sample data. Additionally, the data

used in the present study were recruited from the GEO database, and

not collected specifically for the present study. Since GEO is a

large data repository, a meta-analysis of the relevant datasets for

OS may be performed in the future. Additionally, the OS samples

were obtained from cell lines, while normal samples were obtained

from the human bones of different donors. In addition, the findings

were bioinformatics-based identification and were not validated

using biological experiments. Therefore, further experimental

studies are required.

In conclusion, the present study provided a

comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of differentially methylated

genes which may be involved in the development and progression of

OS. The results of the present study may provide an insight into

the potential pathogenesis of OS. Additionally, functional terms

(potassium ion transport, transmembrane transporter activity and

neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction) and hub genes (NMU and

NMUR1) may serve as potential therapeutic targets for OS. However,

further work is required to improve the diagnosis and treatment of

OS by regulating functional terms.

References

|

1

|

Kobayashi E, Hornicek FJ and Duan Z:

MicroRNA Involvement in Osteosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2012:3597392012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Posthumadeboer J, Witlox MA, Kaspers GJ

and van Royen BJ: Molecular alterations as target for therapy in

metastatic osteosarcoma: A review of literature. Clin Exp

Metastasis. 28:493–503. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

He Y, Cui Y, Wang W, Gu J, Guo S, Ma K and

Luo X: Hypomethylation of the hsa-miR-191 locus causes high

expression of hsa-mir-191 and promotes the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Neoplasia. 13:841–853. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Geiman TM and Robertson KD: Chromatin

remodeling, histone modifications and DNA methylation-how does it

all fit together? J Cell Biochem. 87:117–125. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Flores K, Wolschin F, Corneveaux JJ, Allen

AN, Huentelman MJ and Amdam GV: Genome-wide association between DNA

methylation and alternative splicing in an invertebrate. BMC

Genomics. 13:4802012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhao Y, Sun J, Zhang H, Guo S, Gu J, Wang

W, Tang N, Zhou X and Yu J: High-frequency aberrantly methylated

targets in pancreatic adenocarcinoma identified via global DNA

methylation analysis using methylCap-seq. Clin Epigenetics.

6:182014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jiang F, Todd NW, Li R, Zhang H, Fang H

and Stass SA: A panel of sputum-based genomic marker for early

detection of lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 3:1571–1578.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Guo S, Wang YL, Li Y, Jin L, Xiong M, Ji

QH and Wang J: Significant SNPs have limited prediction ability for

thyroid cancer. Cancer Med. 3:731–735. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhu J and Yao X: Use of DNA methylation

for cancer detection: Promises and challenges. Int J Biochem Cell

Biol. 41:147–154. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hou P, Ji M, Yang B, Chen Z, Qiu J, Shi X

and Lu Z: Quantitative analysis of promoter hypermethylation in

multiple genes in osteosarcoma. Cancer. 106:1602–1609. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lim S, Yang MH, Park JH, Nojima T,

Hashimoto H, Unni KK and Park YK: Inactivation of the RASSF1A in

osteosarcoma. Onco Rep. 10:897–901. 2003.

|

|

12

|

Patiño-García A, Piñeiro ES, Díez MZ,

Iturriagagoitia LG, Klüssmann FA and Ariznabarreta LS: Genetic and

epigenetic alterations of the cell cycle regulators and tumor

suppressor genes in pediatric osteosarcomas. J Pediatr Hematol

Oncol. 25:362–367. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sonaglio V, de Carvalho AC, Toledo SR,

Salinas-Souza C, Carvalho AL, Petrilli AS, de Camargo B and Vettore

AL: Aberrant DNA methylation of ESR1 and p14ARF genes could be

useful as prognostic indicators in osteosarcoma. OncoTargets Ther.

6:713–723. 2013.

|

|

14

|

Lu J, Song G, Tang Q, Zou C, Han F, Zhao

Z, Yong B, Yin J, Xu H, Xie X, et al: IRX1 hypomethylation promotes

osteosarcoma metastasis via induction of CXCL14/NF-κB signaling. J

Clin Invest. 125:1839–1856. 2015. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kresse SH, Rydbeck H, Skårn M, Namløs HM,

Barragan-Polania AH, Cleton-Jansen AM, Serra M, Liestøl K,

Hogendoorn PC, Hovig E, et al: Integrative analysis reveals

relationships of genetic and epigenetic alterations in

osteosarcoma. PLoS One. 7:e482622012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Du P, Kibbe WA and Lin SM: Lumi: A

pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics.

24:1547–1548. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Du P, Zhang X, Huang CC, Jafari N, Kibbe

WA, Hou L and Lin SM: Comparison of Β-value and M-value methods for

quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC

Bioinformatics. 11:5872010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M,

Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D and Beck S: A β-mixture

quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in

Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics.

29:189–196. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu P, Farrell WE, Haworth KE, Emes RD,

Kitchen MO, Glossop JR, Hanna FW and Fryer AA: Maternal genome-wide

DNA methylation profiling in gestational diabetes shows distinctive

disease-associated changes relative to matched healthy pregnancies.

Epigenetics. Mar 16–2016.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

20

|

Olson CF: Parallel Algorithms for

Hierarchical Clustering. Pattern An Mach Int IEEE Trans.

12:1088–1092. 1990. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Sturn A, Quackenbush J and Trajanoski Z:

Genesis: Cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics.

18:207–208. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein

D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT,

et al: Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene

Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 25:25–29. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

da Huang W, Sherman BT and Lempicki RA:

Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID

bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 4:44–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N

and Golani I: Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior

genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 125:279–284. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kanehisa M and Goto S: KEGG: Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:27–30.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

von Mering C, Huynen M, Jaeggi D, Schmidt

S, Bork P and Snel B: STRING: A database of predicted functional

associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:258–261. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL

and Ideker T: Cytoscape 2.8: New features for data integration and

network visualization. Bioinformatics. 27:431–432. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Smith SS: Female sex steroid hormones:

From receptors to networks to performance-actions on the

sensorimotor system. Prog Neurobiol. 44:55–86. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chisari M, Eisenman LN, Krishnan K,

Bandyopadhyaya AK, Wang C, Taylor A, Benz A, Covey DF, Zorumski CF

and Mennerick S: The influence of neuroactive steroid lipophilicity

on GABAA receptor modulation: Evidence for a low-affinity

interaction. J Neurophysiol. 102:1254–1264. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Smith SS: Withdrawal properties of a

neuroactive steroid: Implications for GABA A receptor gene

regulation in the brain and anxiety behavior. Steroids. 67:519–528.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Watanabe M, Maemura K, Oki K, Shiraishi N,

Shibayama Y and Katsu K: Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and cell

proliferation: Focus on cancer cells. Histol Histopathol.

21:1135–1141. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Szczaurska K, Mazurkiewicz M and Opolski

A: The role of GABA-ergic system in carcinogenesis. Postepy Hig Med

Dosw. 57:485–500. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Moon MS, Cho EW, Byun HS, Jung IL and Kim

IG: GAD 67KD antisense in colon cancer cells inhibits cell growth

and sensitizes to butyrate and pH reduction and H2O2 and

gamma-radiation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 430:229–236. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kleinrok Z, Matuszek M, Jesipowicz J,

Matuszek B, Opolski A and Radzikowski C: GABA content and GAD

activity in colon tumors taken from patients with colon cancer or

from xenografted human colon cancer cells growing as s.c. Tumors in

athymic nu/nu mice. J Physiol Pharmacol. 49:303–310.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kunzelmann K: Ion Channels and Cancer. J

Membr Biol. 205:159–173. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Pardo LA and Stuhmer W: Eag1: An emerging

oncological target. Cancer Res. 68:1611–1613. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Voloshyna I, Besana A, Castillo M, Matos

T, Weinstein IB, Mansukhani M, Robinson RB and Cordon-Cardo C:

TREK-1 is a novel molecular target in prostate cancer. Cancer Res.

68:1197–1203. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Weaver AK, Bomben VC and Sontheimer H:

Expression and function of calcium-activated potassium channels in

human glioma cells. Glia. 54:223–233. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pluznick JL and Sansom SC: BK channels in

the kidney: Role in K(+) secretion and localization of molecular

components. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 291:F517–F529. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Weaver AK, Liu X and Sontheimer H: Role

for calcium-activated potassium channels (BK) in growth control of

human malignant glioma cells. J Neurosci Res. 78:224–234. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wei WC, Akerman CJ, Newey SE, Pan J,

Clinch NW, Jacob Y, Shen MR, Wilkins RJ and Ellory JC: The

potassium-chloride cotransporter 2 promotes cervical cancer cell

migration and invasion by an ion transport-independent mechanism. J

Physiol. 589:5349–5359. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Rezzonico R, Schmid-Alliana A, Romey G,

Bourget-Ponzio I, Breuil V, Breittmayer V, Tartare-Deckert S, Rossi

B and Schmid-Antomarchi H: Prostaglandin E2 induces interaction

between hSlo potassium channel and Syk tyrosine kinase in

osteosarcoma cells. J Bone Miner Res. 17:869–878. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wu J, Zhong D, Wu X, Sha M, Kang L and

Ding Z: Voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 is highly expressed

in human osteosarcoma and promotes osteosarcoma growth. Int J Mol

Sci. 14:19245–19256. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Macheda ML, Rogers S and Best JD:

Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT)

proteins in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 202:654–662. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Moley KH and Mueckler MM: Glucose

transport and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 5:99–105. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lorenz HM, Herrmann M, Winkler T, Gaipl U

and Kalden JR: Role of apoptosis in autoimmunity. Apoptosis.

5:443–449. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Schulze-Bergkamen H and Krammer PH:

Apoptosis in cancer-implications for therapy. Semin Oncol.

31:90–119. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wyllie AH: Apoptosis and the regulation of

cell numbers in normal and neoplastic tissues: An overview. Cancer

Metastasis Rev. 11:95–103. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Deeley RG, Westlake C and Cole SP:

Transmembrane transport of endo-and xenobiotics by mammalian

ATP-binding cassette multidrug resistance proteins. Physiol Rev.

86:849–899. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Fujii R, Hosoya M, Fukusumi S, Kawamata Y,

Habata Y, Hinuma S, Onda H, Nishimura O and Fujino M:

Identification of neuromedin U as the cognate ligand of the orphan

G protein-coupled receptor FM-3. J Biol Chem. 275:21068–21074.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Moriyama M, Sato T, Inoue H, Fukuyama S,

Teranishi H, Kangawa K, Kano T, Yoshimura A and Kojima M: The

neuropeptide neuromedin U promotes inflammation by direct

activation of mast cells. J Exp Med. 202:217–224. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Harten SK, Esteban MA, Shukla D, Ashcroft

M and Maxwell PH: Inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumour

suppressor gene induces Neuromedin U expression in renal cancer

cells. Mol Cancer. 10:892011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kohno Y: Oral cancer in vivo gene

expression profiling assisted by laser capture microdissection and

microarray analysis. Oncogene. 20:6196–6204. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Shetzline SE, Rallapalli R, Dowd KJ, Zou

S, Nakata Y, Swider CR, Kalota A, Choi JK and Gewirtz AM:

Neuromedin U: A Myb-regulated autocrine growth factor for human

myeloid leukemias. Blood. 104:1833–1840. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|