Introduction

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third most common

form of cancer in the world, and the rectum exhibits common

internal malignancies (1). In

China, CRC ranks 5th among cancer deaths, with increasing the

incidence annually (2). Although

there are treatment options including radiotherapeutic,

chemotherapeutic regimens and surgical regimens available for the

clinical management of CRC, outcomes of such strategies are limited

by associated high probability of cancer recurrence, obvious

toxicity on the human body, affecting neurotoxicity,

gastrointestinal reaction, kidney failure, and cardiotoxicity

(3,4). Chemoprevention is a strategy that was

first proposed by Sporn et al (5). It is a way to reverse, suppress, or

prevent molecular or histologic premalignant lesions from

progressing to invasive cancer by using natural or synthetic agents

(6). To date, many food/plant

derived chemopreventive agents that exhibit strong efficacy against

various cancers in vitro and preclinical models have been

identified (7–10). Colorectal carcinoma is a rationale

cancer to target for chemoprevention studies due to high incidence

of pre-neoplastic lesions and cancerous tumors (11). An ideal chemopreventive compound

should be nontoxic, potent, highly effective, less expensive, and

easily available (4).

Luteolin (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone), a

flavonoid polyphenolic compound found in many plant types such as

fruits, vegetables, and medicinal herbs. It has been shown

biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy, and

anticancer activities (12–14).

Recent studies have reported the anticancer effects of luteolin

against lung cancer, head and neck cancer, prostate, breast, colon,

liver, cervical, and skin cancer was associated with inducing

apoptosis, suppressing metastasis, and angiogenesis (15–22).

These results of above studies warrant the further evaluation of

the chemopreventive potential of luteolin in human subjects

(4). However, it has very low

bioavailability after oral administration and it is very difficult

to make intravenous or intraperitoneal administration because of

its poor aqueous solubility. Therefore, there is a clear need to

increase its potential in clinical application (23).

During the past few years, liposomes have drawn much

attention for cancer therapy because of longer blood circulation

time, higher biocompatibility, excellent bioavailability, and

higher tumor-specific delivery (24–27).

Thus, in the present study, we investigated whether liposomes can

be used as delivery system to improve the antitumor efficacy of

luteolin in vitro and in vivo. We used CT26 cell and

mouse tumor model to evaluate the activity of luteolin before and

after encapsulating into liposome. Meanwhie, we established a

liposome-formulated luteolin that is capable of effective

suppressing tumor growth through inducing apoptosis and inhibiting

angiogenesis. It is our hope that understanding of these mechanisms

in detail may provide a basis for novel targeting strategies for

cancers.

Materials and methods

Liposome preparation

Lipo-Lut formulations were prepared by the thin film

hydration method. Briefly, the mixtures of

luteolin/cholesterol/lecithin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany) in 1:2:7 weight ratios were dissolved in

ethanol and were transferred into a round bottom flask. The flask

was then connected to a rotary evaporator at 50 rpm and water bath

with temperature maintained at 40°C. Vacuum was applied to the

flask to evaporate the ethanol and form a homogeneous lipid film on

the flask wall. Then the lipid film was then hydrated in normal

saline by rotating the flask at 37°C until the lipid film was

completely hydrated. At last the luteolin liposome was sonicated

with 50 watts of power for 10 min. The empty liposome without

luteolin was prepared in the same as the Lipo-Lut.

Size distribution and ζ-potential

The mean particle sizes and ζ-potential of the

obtained liposomes were measured by photon correlation spectroscopy

using Malvern Zeta sizer 3000 HS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK)

at 25°C. The form feature of the liposomes was determined by

transmission electron microscope (TEM) (H-600; Hitachi, Tokyo,

Japan) using a negative staining method with 1% sodium

phosphotungstate solution for 2 min at room temperature.

Drug loading and encapsulation

efficiency

The prepared liposomes were solubilized in methanol

[liposomes: methanol=1:9, volume/volume (v/v)]. After using a

cyclomixer to completely extract the drug from lipid to methanol,

the drug content was analyzed by an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC System

(Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). An octadecylsilyl

column (4.6×250.0 mm, 5 µm) was used for the analysis. The mobile

phase was a mixture of acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid (30:70,

v/v), and the flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. The UV detection wavelength

of 350 nm was used, the column temperature was 35°C. The amount of

soluble unencapsulated drug was measured by ultrafiltration using

centrifugal filter tubes with a molecular weight cut-off of 300 kDa

(Millipore, Carrigtwohill, Ireland). Drug loading and encapsulation

efficiency were calculated using following equations 1 and 2, respectively. The data were obtained

using three different batches of liposome preparations.

Drug loading(%)=CsClipidx100%

Encapsulation efficiency(%)=CsCtotlax100%

Where Cs represents drug mass in

liposome, Clipid represents total liposome mass, and

Ctotal represents total drug mass.

Drug release

The release of luteolin from liposomes in

vitro was measured with a dialysis method. Lipo-Lut solution

(0.5 ml) and Free-Lut (0.5 ml) in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO)

solution were placed in a dialysis bag (MW cut off: 3500 Da). After

that, dialysis bag was placed in a 50 ml PBS supplemented with 0.5%

Tween-20 (PBST). This bottle was introduced in a shaking incubator

with stirring speed of 100 rpm at 37°C. At specific time intervals

(0, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120 h), samples were

withdrawn and replaced with an equal volume of medium. The amount

of luteolin released at each time-point was determined using HPLC,

as described earlier. All assays were performed in triplicate.

To measure in vivo pharmacokinetics, BALB/c

mice, weighting 18–20 g were randomly divided into two groups (six

animals per time-point) for treatment with Free-Lut or Lipo-Lut at

a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight via intravenous injection. After

dosing, blood was immediately collected via cardiac puncture at 5,

15, 30, 45, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24 h and centrifuged at 8,000

rpm for 10 min to separate the plasma. The diphenhydramine was

added to plasma samples as the internal standard, and acetonitrile

as protein precipitator. The drug was then extracted from plasma

samples and processed for HPLC analysis to determine luteolin

levels.

MTT assay

The murine CT26 colorectal carcinoma cell line was

obtained from the ATCC, and it was maintained in RPMI-1640

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C. The inhibition of luteolin to

CT26 cell was determined by the MTT assay. Briefly, cells in the

logarithmic growth phase (3×103 or

5×103/well) were placed in wells of a 96-well plate at

37°C overnight. Cells were then treated with various concentrations

of Free-Lut or Lipo-Lut and cultured for 24. After an additional 3

h of culture with 0.5 mg/ml MTT at 37°C, 150 µl DMSO was added to

each well to dissolve formazan crystals. The cells which received

only the medium containing 150 µl DMSO served as the control group.

All of samples were analyzed using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The test was repeated three

times. The cell viability was assessed as a percentage of the

absorbance present in the drug-treated cells compared to that in

the control cells.

Assessment of apoptosis

The apoptotic rate of CT26 cells were detected by

flow cytometry using the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.,

Santa Cruz, CA, USA). CT26 cells cultured in 6-well plates were

treated with various concentrations of Free-Lut or Lipo-Lut, along

with no drug treatment as control. After incubation for 24 h at

37°C, cells were trypsinized, washed and resuspended in PBS. The

cells were subsequently treated with Annexin V-FITC and PI in the

dark for 15 min. Flow cytometry analysis was performed with an

EpicsXL Coulter flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA,

USA) and repeated thrice.

Mouse tumor model

Female BALB/c mice, 6 weeks old and weighting 18–20

g, was obtained from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd. (Beijing,

China). The mice were kept in specific pathogen free (SPF)

conditions for 1 week prior to start of experimental procedures.

All the animal experiments were evaluated and approved by the

Animal and Ethics Review Committee of Xinjiang Medical University

(Urumqi, Xinjiang). The murine tumor models were established by

subcutaneous inoculation in the right flanks of female BALB/c mice

with CT26 cells (1×106/mouse). The growth of the tumor

was monitored, and tumor volumes were calculated from vernier

calipers every 3 days, following the formula of 0.52 × length ×

width2. The drug treatments were initiated when tumors

had reached an average volume of 100 mm3, which occurred

around day 7 post-cell inoculation. The luteolin dose administered

to the mice was 50 mg/kg. The mice were randomly assigned into four

groups (six animals per group). Each group was respectively treated

with normal saline (NS), empty liposome (EM-Lipo), Free-Lut, and

Lipo-Lut via the tail vein every 2 days a total of five times.

After the last treatment, the mice were sacrificed on the day 22,

and the tumors were excised, weighed and fixed in 10% neutral

buffered formalin solution or frozen at −80°C.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining and immunofluorescence staining

CT26 xenograft specimens were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 12 h and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5-µm

thick) were cut, dewaxed, rehydrated, and stained with H&E. To

observe the inhibitory effect on neovascularization, the frozen

tissues were sectioned (5 µm) and fixed in acetone. The tissues

sections were incubated with monoclonal anti-CD31 antibody (Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 4°C overnight, flowing stained with a

secondary goat antibody (FITC). The number of microvessels per

high-power field was counted in sections. The immunofluorescence of

Ki-67 expression in tumor was done as follows: Tissue sections were

incubated with monoclonal anti-Ki67 antibody followed by incubation

with FITC labelled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). Tissue apoptotic cells were detected with

TUNEL Detection kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. All the slides were evaluated by

fluorescence microscope. Five areas were randomly selected from

each slide for analysis.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistics 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA) were used for statistical analysis. Quantitative data were

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent

experiments and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Comparison between the

groups was made by analyzing data with S-N-K method. A P-value

<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Characterization of Lipo-Lut

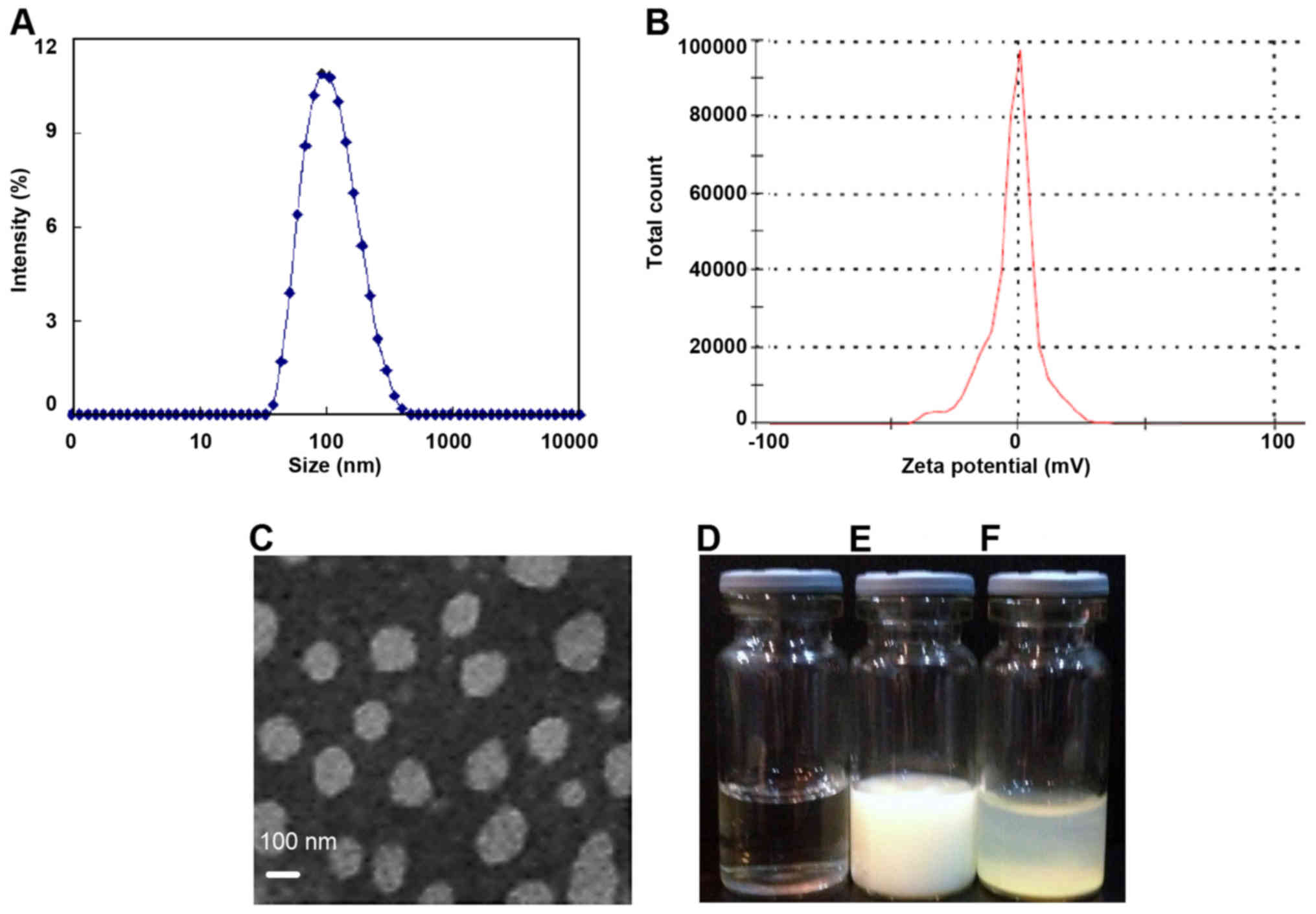

Our results demonstrated the successful application

of the thin-film hydration method to formulate the water soluble

Lipo-Lut. As shown in Fig. 1,

dynamic light scattering results showed that the diameter of

Lipo-Lut was around 105 nm. The ζ-potential of Lipo-Lut was 0.12

mv. The morphology of Lipo-Lut was observed using TEM, most

Lipo-Lut was spherical and had a regular shape. Free-Lut appeared

stratified in water, had apparent precipitation in the bottom of

the bottle. Lipo-Lut can be stably suspended in water solution.

Consequently, the drug loading and encapsulation efficiency were

found to be 10 and 90%, for the Lipo-Lut formulation.

Drug release and Pharmacokinetics of

Lipo-Lut

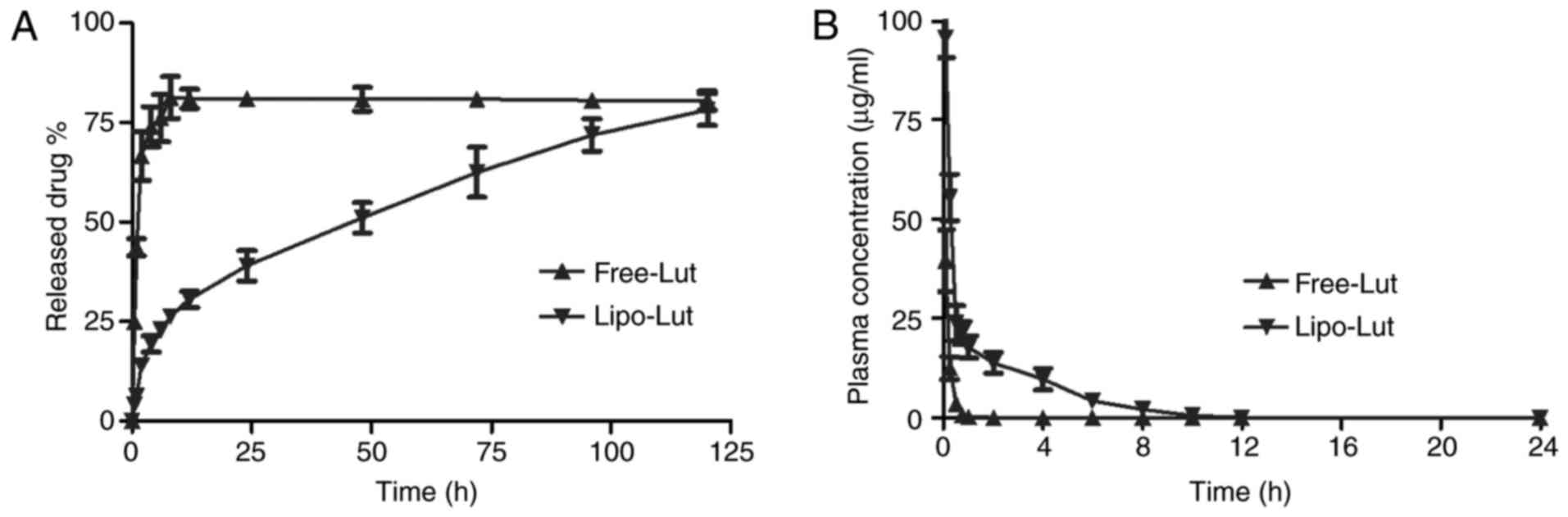

The in vitro release (Fig. 2A) results showed that the luteolin

can be released slowly from the liposomes and then Free-Lut was

released very quickly. The cumulative percentage release

demonstrated that the amount of drug released from liposomes was

gradually increased over time, and after 120 h there was an

increase of over 80%. The free drug exhibited high level (80%) at 8

h.

To assess whether the liposome improved

bioavailability of poor water soluble drugs, the mean plasma

concentration-time profiles of luteolin after intravenous

administration of free and liposome drug were presented in Fig. 2B. Free-Lut was rapidly cleared and

the plasma levels of luteolin were less than 50% of the injected

dose within 5 min of injection. Compared to free drug, luteolin

concentration in plasma was almost 10-fold higher for Lipo-Lut at 2

h after drug injection, a result that was most evident at

time-points beyond 1 h. The results demonstrated that liposomal

encapsulation reduced drug elimination.

Lipo-Lut demonstrated better

tumoricidal effect on colorectal cancer cells than the

Free-Lut

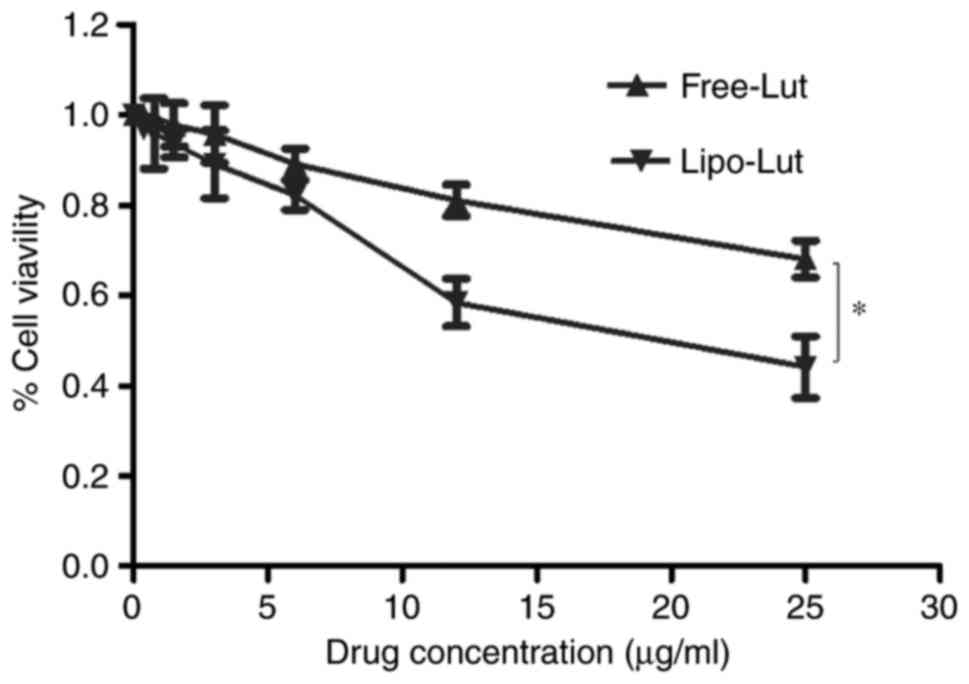

Lipo-Lut and Free-Lut were evaluated for inhibition

against CT26 cells using MTT assay. The results (Fig. 3) clearly established that Lipo-Lut

exhibited potent inhibitory effect, as similar to Free-Lut.

Further, both drugs showed dose-dependent inhibition of cell

growth. After the incubation of the cells with Lipo-Lut or Free-Lut

for 24 h, the Lipo-Lut showed significantly higher inhibition

compared to the Free-Lut at all the concentrations tested. In

contrast, the empty liposomes did not show any toxicity to the

cells (data not shown). These data indicated that Lipo-Lut

inhibited tumor proliferation in vitro.

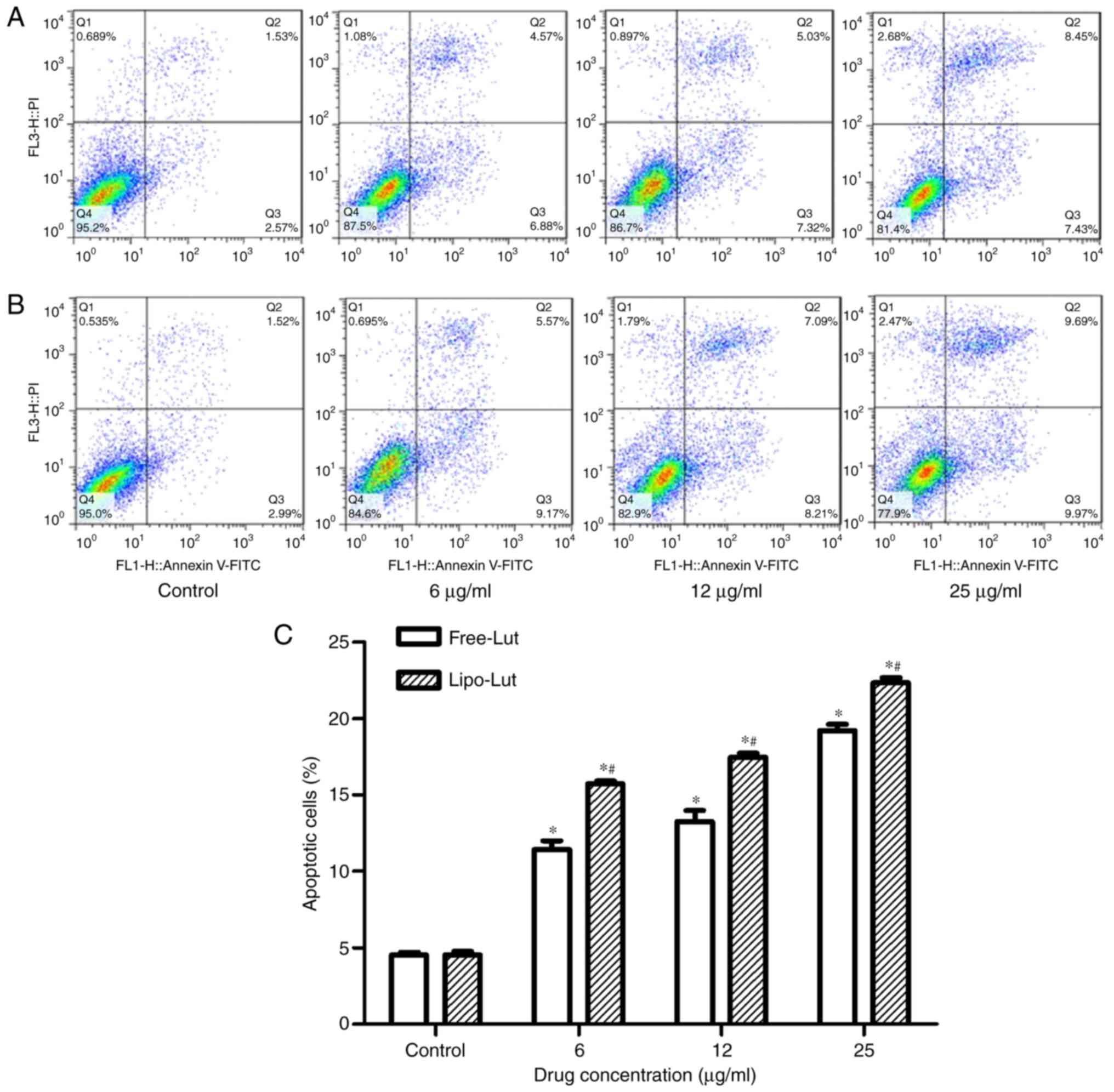

Next, we determined whether the inhibitory effect of

Lipo-Lut involved the initiation of apoptosis. A flow cytometry

analysis of Annexin V staining for phosphatidylserine, an early

apoptosis marker, was performed for evaluation of apoptotic

cells-after incubating CT26 cells with Lipo-Lut or Free-Lut at

various concentrations. The cells were collected and stained with

Annexin V-FITC and PI. When the cells undergoing apoptosis, the

phosphatidylserine normally located in the inner leaflet of the

cellular membrane translocates to the outer leaflet of the plasma

membrane at the early stages of apoptosis, which can be labeled

with Annexin V-FITC. Viable cells with intact membranes exclude PI

whereas the membranes of dead and damaged cells are permeable to

PI. CT26 cells were divided into four groups, ie, necrotic cells

(upper left quadrant, Annexin V−/PI+),

healthy viable cells (lower left quadrant, Annexin

V−/PI−), cells in the early apoptosis stage

(lower right quadrant, Annexin V+/PI−), and

cells that are in late apoptosis or already dead (upper right

quadrant, Annexin V+/PI+). As shown in

Fig. 4, more than 95% of control

CT26 cells (control) were viable whereas all the cells incubated

with Lipo-Lut or Free-Lut displayed evidence of apoptosis. The

percentage of early apoptotic cells and late apoptotic cells in

Lipo-Lut or Free-Lut were showed dose dependence. Meanwhile, the

extent of apoptosis in the Lipo-Lut group was significantly higher

than Free-Lut group.

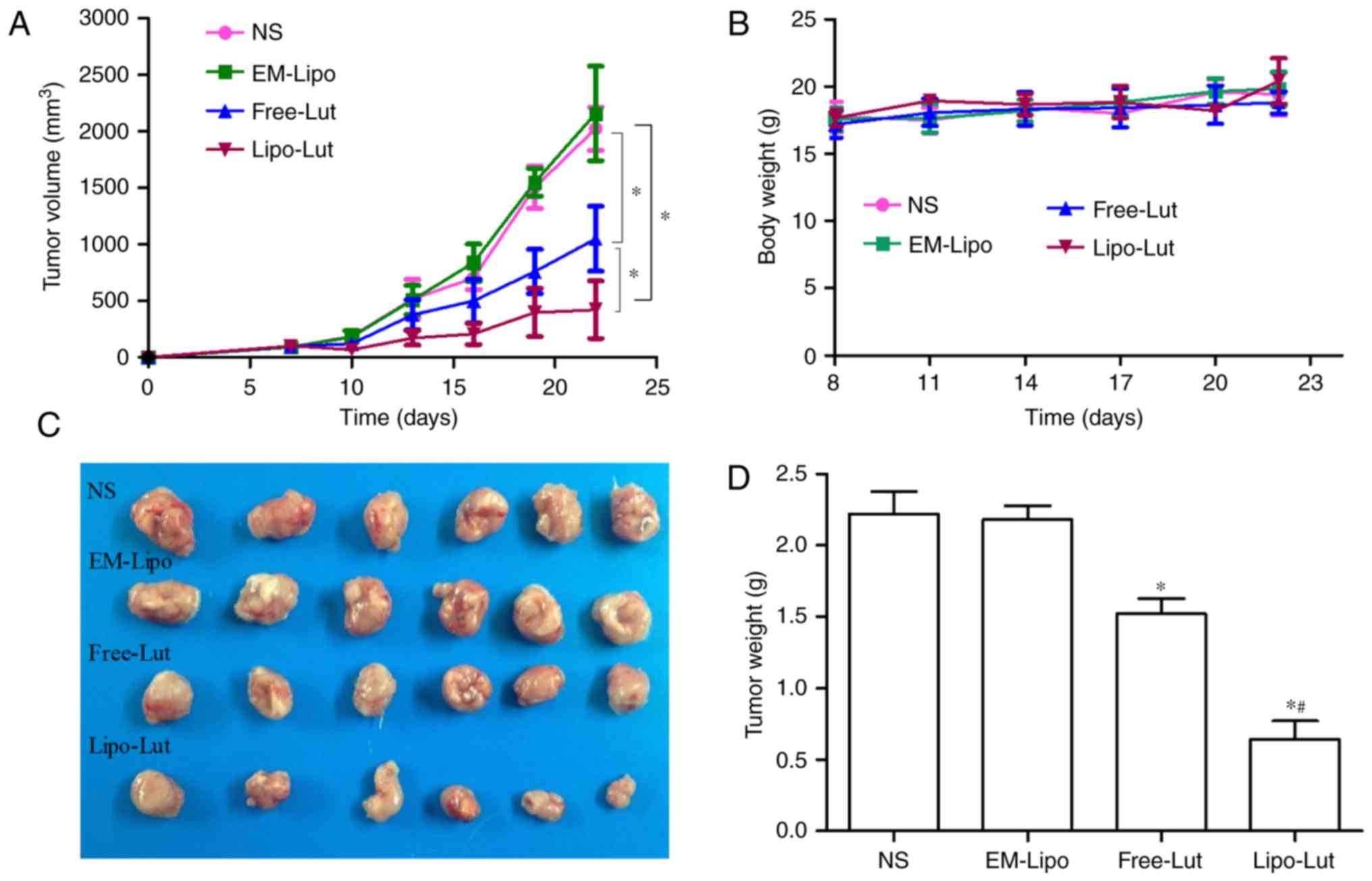

Lipo-Lut demonstrated better

tumoricidal effect on the mouse tumor model than the Free-Lut

To validate antitumor efficiency of Lipo-Lut in

vivo, we used a CT26 colorectal carcinoma graft model in BALB/c

mice (Fig. 5). Fig. 5A displayed the tumor volume of each

group during the 22-day treatment. Compared to the NS and EM-Lipo,

the final tumor volume of mice treated with luteolin was notably

reduced. The Lipo-Lut group exhibited the most significant

inhibitory efficacy compared with the other groups. There was no

significant difference between NS group and EM-Lipo group. At the

end of the treatment, the tumor weights were obtained (Fig. 5D), the results were consistent with

the tumor volumes at the end of the treatment. The smallest tumor

weights were observed in the Lipo-Lut group among the four groups.

These results indicated that the treatment of Lipo-Lut resulted in

a robust efficacy in reducing tumor volume. Body weights were not

significantly different in the four groups throughout the whole

experiment (Fig. 5B).

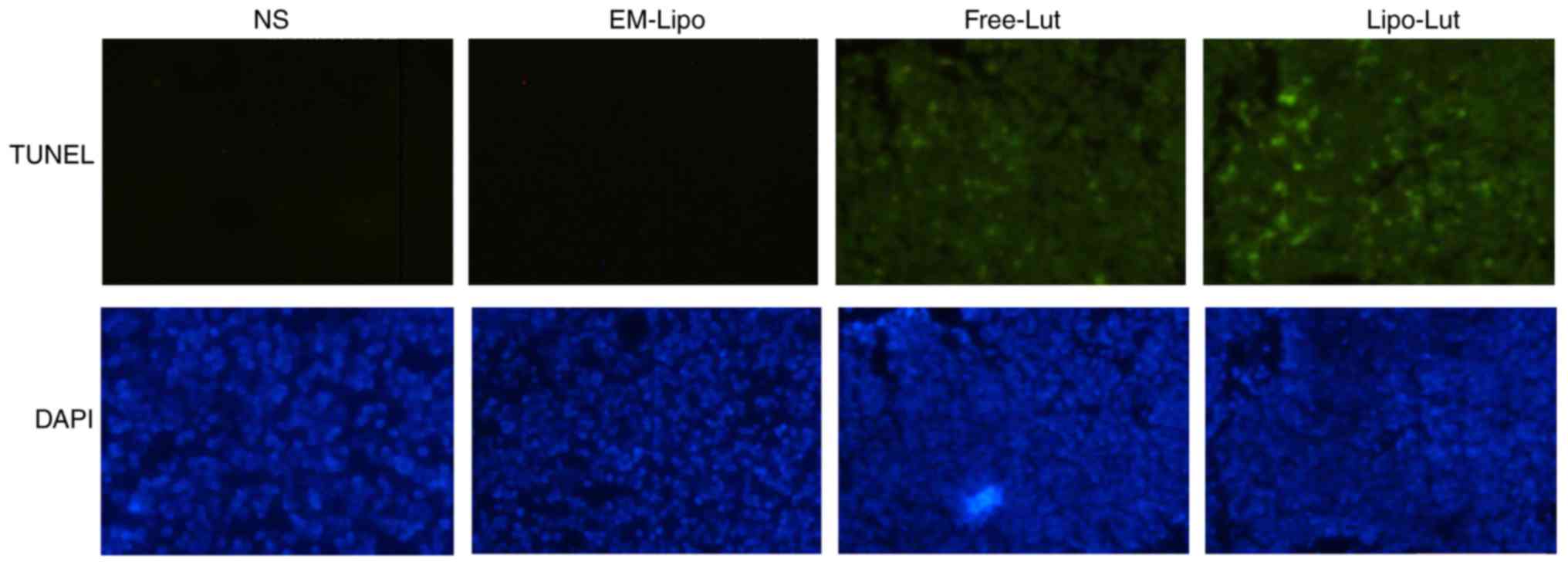

Lipo-Lut induced apoptosis

To further investigated whether the in vivo

antitumor effects of the Lipo-Lut were associated with enhanced

induction of the apoptotic cells, TUNEL assay was applied. As shown

in Fig. 6, a significant number of

apoptotic cells appeared with green fluorescence in the tumor

tissue of luteolin-treated mice. Treatment with Lipo-Lut clearly

produced more pronounced apoptotic cells than treatment with the

Free-Lut. These results suggested that Lipo-Lut inhibited tumor

growth probably through induction of tumor cellular apoptosis.

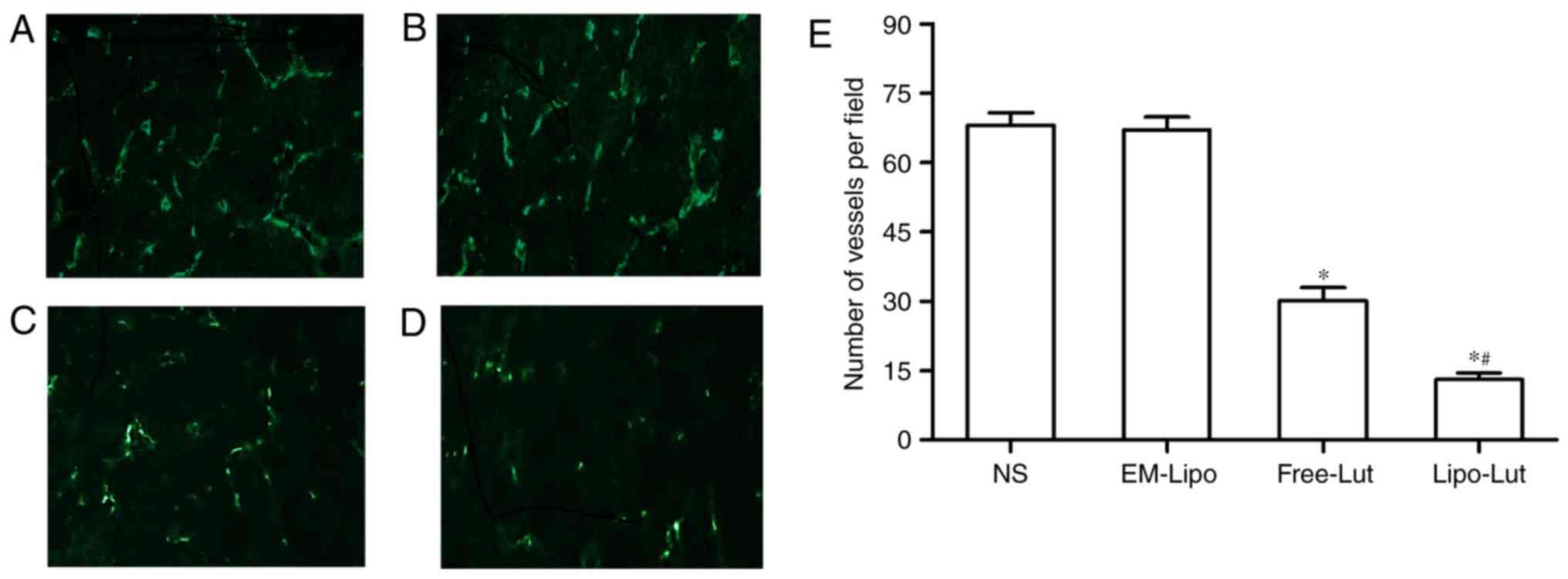

Lipo-Lut inhibited tumor

vascularization

We performed immunofluorescence analysis with

anti-CD31 monoclonal antibody to observe the new vasculature

content in frozen tumor sections (Fig.

7). As shown in Fig. 7D,

CD31-positive endothelial cells in luteolin treated groups had

weaker fluorescence than those of NS group and EM-Lipo group

(Fig. 7A and B). The results from

the determination of microvessel numbers (Fig. 7E) revealed that there were

significantly less number of microvessels present in the Free-Lut

group and Lipo-Lut group compared to the control group (P<0.01).

In addition, Lipo-Lut group reduced number of microvessels more

remarkably compared with Free-Lut groups (P<0.01). No

significant difference was observed between NS group and EM-Lipo

group (P>0.05).

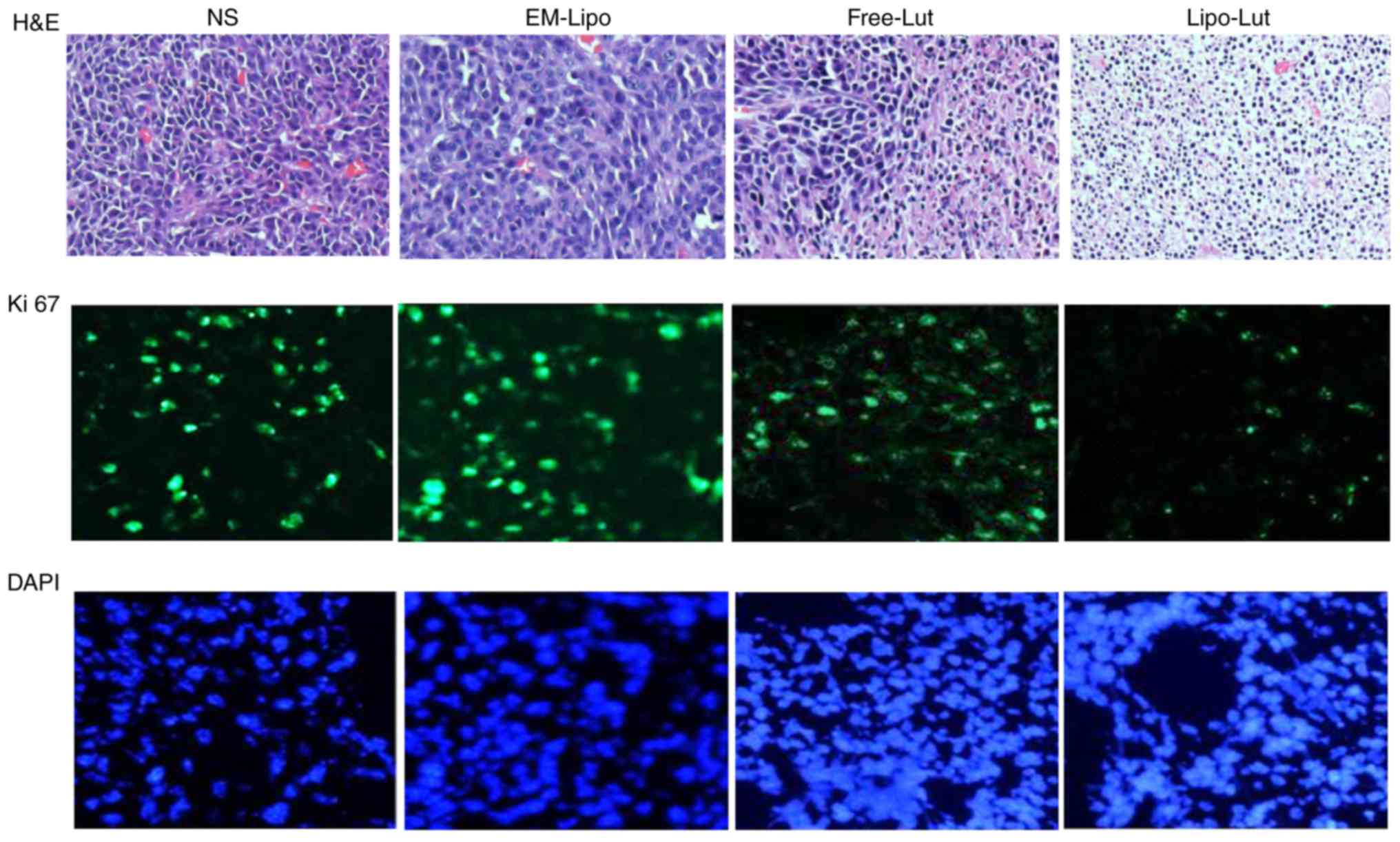

Lipo-Lut decreased Ki-67

expression

The expression of Ki-67 is strictly associated with

tumor cell proliferation and growth, and is widely used in routine

pathological investigation as a proliferation marker and a

diagnosis tool (28).

Immunofluorescence examination of Ki-67 staining revealed a greater

inhibition of proliferating cells in the Lipo-Lut-treated mice than

other groups (Fig. 8).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that

liposome-encapsulated luteolin exerted stronger tumor

growth-inhibition than free luteolin both in vitro and in

vivo. Liposome have been widely used as potential drug delivery

systems (DDS) for delivery of anti-cancer agents (24,29).

Over the past few decades, several liposome-encapsulated drugs have

been approved for clinic applications. The best-known formulation

is liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin, marketed as Doxil or Caelyx

(30–32), which produced less cardiotoxicity

than free doxorubicin while providing comparable antitumor activity

(33,34). In our study, we have prepared water

soluble Lipo-Lut, sized ~105 nm. According to the cancer type, the

size of the gaps between the endothelial cells of the tumor

capillaries ranges from 100 to 780 nm, as opposed to that in a

typical normal endothelium of 5–10 nm (35,36).

Liposomes of about 100 nm in diameter have been demonstrated to be

optimal for the delivery of anticancer drugs to tumors (24,37),

which readily translocate across the capillary endothelium.

Liposomes are known to be safe and well tolerated delivery system.

Many researchers demonstrated that the actions of some poor water

soluble drugs were evidently enhanced after they were encapsulated

into liposome (38,39). This study showed that Lipo-Lut

could prolong the drug release. Meanwhile, the concentration in

plasma-time profiles indicated that the bioavailability of Lipo-Lut

has been improved.

In order to study the antitumor efficacy of Lipo-Lut

in vitro, we initially compared the efficacy of Free-Lut and

Lipo-Lut on CT26 cell growth inhibition by MTT assay and apoptosis

by flow cytometry. We observed that Lipo-Lut exhibited more

effectively than Free-Lut. This prompted us to further evaluate the

antitumor activities of Lipo-Lut on CT26 cells grafts in BALB/c

mice. The results suggested that luteolin encapsulated into

liposome exerted stronger tumor growth-inhibiting effects,

suppressed angiogenesis, increased apoptosis than Free-Lut.

Angiogenesis plays a important role in the progress of tumor growth

and invasion. The most essential angiogenic factors is vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF). It have been reported that

luteolin could significantly inhibit VEGF-stimulated endothelial

cell proliferation, migration, invasion and tumor angiogenesis by

targeting VEGF receptor 2-regulated AKT/ERK/mTOR/P70S69K/MMPs

pathway, leading to the inhibition of tumor growth and tumor

angiogenesis. A study from Norhaizan suggested that luteolin

induced apoptosis in colon cancer by modulating the expressions of

bax, Bcl-2 and caspase 3 in vitro and in vivo. On the

other hand luteolin acted against DNA damage and activated DNA

repair mechanism in Caco-2 colon cancer cells (40–42).

Moreover, Owing to the leaky vasculature of the tumor tissue, these

may provide a channel allowing liposome to more easily target tumor

tissue (1). Meanwhile, solid

tumors usually lack effective lymphatic drainage. All of these

factors lead to the accumulation of liposome in the tumor

microenvironment much more than they do in normal tissues (43,44).

Most likely because of a combination of these advantages, Lipo-Lut

was a marked inhibition of tumor growth over time when compared to

Free-Lut in a mouse tumor model. In fact, the present study also

indicated that Nano-luteolin showed higher efficacy compared to

Free-Lut against lung cancer and head and neck cancer (4). However, Lipo-Lut was unable to

completely inhibit tumor growth. In order to gain better

therapeutic efficacy, it is necessary to optimize liposomal

formations and therapeutic scheme.

We prepared a novel antitumor agent using liposome

as the delivery system to encapsulate luteolin. The Lipo-Lut

inhibited activity of tumor growth more effectively than the

Free-Lut in both CT26 cells and mouse tumor model of colorectal

carcinoma. The mechanisms of action of Lipo-Lut appear

multifaceted. Firstly, it could directly induce apoptosis of tumor

cells. Secondly, tumor angiogenesis were reduced, blocking the

nutrition supply into tumor tissue, which promoted apoptosis of

tumor cells. Third, Lipo-Lut inhibited tumor proliferation. The

results in this study could contribute to the development of

chemotherapy for patients with colorectal carcinoma in future

clinical applications.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation, People's Republic of China (grant no. 81660480)

and Scientific Research Project of Xinjiang University (grant no.

XJEDU2014I019).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

Lut

|

luteolin

|

|

NS

|

normal saline

|

|

Lipo-Lut

|

liposomal luteolin

|

|

Free-Lut

|

free luteolin

|

|

EM-Lipo

|

empty liposome

|

References

|

1

|

Yang C, Liu HZ, Fu ZX and Lu WD:

Oxaliplatin long-circulating liposomes improved therapeutic index

of colorectal carcinoma. BMC Biotechnol. 11:212011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Nobili S, Checcacci D, Filippelli F, Del

Buono S, Mazzocchi V, Mazzei T and Mini E: Bimonthly chemotherapy

with oxaliplatin, irinotecan, infusional 5-fluorouracil/folinic

acid in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer pretreated with

irinotecan- or oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. J Chemother.

20:622–631. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen AY and Chen YC: A review of the

dietary flavonoid, kaempferol on human health and cancer

chemoprevention. Food Chem. 138:2099–2107. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Majumdar D, Jung KH, Zhang H, Nannapaneni

S, Wang X, Amin AR, Chen Z, Chen ZG and Shin DM: Luteolin

nanoparticle in chemoprevention: In vitro and in vivo anticancer

activity. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 7:65–73. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sporn MB, Dunlop NM, Newton DL and Smith

JM: Prevention of chemical carcinogenesis by vitamin A and its

synthetic analogs (retinoids). Fed Proc. 35:pp. 1332–1338. 1976;

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Madhunapantula SV and Robertson GP:

Chemoprevention of melanoma. Adv Pharmacol. 65:361–398. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mann CD, Neal CP, Garcea G, Manson MM,

Dennison AR and Berry DP: Phytochemicals as potential

chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agents in

hepatocarcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 18:13–25. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Khor TO, Yu S and Kong AN: Dietary cancer

chemopreventive agents-targeting inflammation and Nrf2 signaling

pathway. Planta Med. 74:1540–1547. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kaur M, Singh RP, Gu M, Agarwal R and

Agarwal C: Grape seed extract inhibits in vitro and in vivo growth

of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 12:6194–6202.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kaur M, Velmurugan B, Tyagi A, Agarwal C,

Singh RP and Agarwal R: Silibinin suppresses growth of human

colorectal carcinoma SW480 cells in culture and xenograft through

down-regulation of beta-catenin-dependent signaling. Neoplasia.

12:415–424. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Benbrook DM, Guruswamy S, Wang Y, Sun Z,

Mohammed A, Zhang Y, Li Q and Rao CV: Chemoprevention of colon and

small intestinal tumorigenesis in APC(min/+) mice by SHetA2

(NSC721689) without toxicity. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 6:908–916.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang MY, Wang CJ, Chen NF, Ho WH, Lu FJ

and Tseng TH: Luteolin enhances paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in

human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells by blocking STAT3. Chem Biol

Interact. 213:60–68. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Huang X, Dai S, Dai J, Xiao Y, Bai Y, Chen

B and Zhou M: Luteolin decreases invasiveness, deactivates STAT3

signaling and reverses interleukin-6 induced epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and matrix metalloproteinase secretion of pancreatic

cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 8:2989–3001. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yan M, Liu Z, Yang H, Li C, Chen H, Liu Y,

Zhao M and Zhu Y: Luteolin decreases the UVA-induced autophagy of

human skin fibroblasts by scavenging ROS. Mol Med Rep.

14:1986–1992. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee HZ, Yang WH, Bao BY and Lo PL:

Proteomic analysis reveals ATP-dependent steps and chaperones

involvement in luteolin-induced lung cancer CH27 cell apoptosis.

Eur J Pharmacol. 642:19–27. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ong CS, Zhou J, Ong CN and Shen HM:

Luteolin induces G1 arrest in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

via the Akt-GSK-3β-cyclin D1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 298:167–175.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chiu FL and Lin JK: Downregulation of

androgen receptor expression by luteolin causes inhibition of cell

proliferation and induction of apoptosis in human prostate cancer

cells and xenografts. Prostate. 68:61–71. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cai X, Ye T, Liu C, Lu W, Lu M, Zhang J,

Wang M and Cao P: Luteolin induced G2 phase cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis on non-small cell lung cancer cells. Toxicol In Vitro.

25:1385–1391. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Balyan R, Kudugunti SK, Hamad HA, Yousef

MS and Moridani MY: Bioactivation of luteolin by tyrosinase

selectively inhibits glutathione S-transferase. Chem Biol Interact.

240:208–218. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu JF, Ma Y, Wang Y, Du ZY, Shen JK and

Peng HL: Reduction of lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells by luteolin

is associated with activation of AMPK and mitigation of oxidative

stress. Phytother Res. 25:588–596. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Abdel Hadi L, Di Vito C, Marfia G,

Ferraretto A, Tringali C, Viani P and Riboni L: Sphingosine kinase

2 and ceramide transport as key targets of the natural flavonoid

luteolinto induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells. PLoS One.

10:e01433842015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wölfle U, Esser PR, Simon-Haarhaus B,

Martin SF, Lademann J and Schempp CM: UVB-induced DNA damage,

generation of reactive oxygen species and inflammation are

effectively attenuated by the flavonoid luteolin in vitro and in

vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 50:1081–1093. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu Y, Wang L, Zhao Y, He M, Zhang X, Niu

M and Feng N: Nanostructured lipid carriers versus microemulsions

for delivery of the poorly water-soluble drug luteolin. Int J

Pharm. 476:169–177. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yuan Y, Zhao Y, Xin S, Wu N, Wen J, Li S,

Chen L, Wei Y, Yang H and Lin S: A novel PEGylated

liposome-encapsulated SANT75 suppresses tumor growth through

inhibiting hedgehog signaling pathway. PLoS One. 8:e602662013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fetterly GJ, Grasela TH, Sherman JW, Dul

JL, Grahn A, Lecomte D, Fiedler-Kelly J, Damjanov N, Fishman M and

Kane MP: Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling and simulation of

neutropenia during phase I development of liposome-entrapped

paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 14:5856–5863. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, Kaufman B,

Safra T, Cohen R, Martin F, Huang A and Barenholz Y: Prolonged

circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of

doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes.

Cancer Res. 54:987–992. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Guo L, Fan L, Ren J, Pang Z, Ren Y, Li J,

Wen Z, Qian Y, Zhang L and Ma H: Combination of TRAIL and

actinomycin D liposomes enhances antitumor effect in non-small cell

lung cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 7:1449–1460. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Li LT, Jiang G, Chen Q and Zheng JN: Ki67

is a promising molecular target in the diagnosis of cancer

(Review). Mol Med Rep. 11:1566–1572. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Koudelka S, Turanek Knotigova P, Masek J,

Prochazka L, Lukac R, Miller AD, Neuzil J and Turanek J: Liposomal

delivery systems for anti-cancer analogues of vitamin E. J Control

Release. 207:59–69. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Barenholz Y: Doxil® - the first

FDA-approved nano-drug: Lessons learned. J Control Release.

160:117–134. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Schiffelers RM, Metselaar JM, Fens MH,

Janssen AP, Molema G and Storm G: Liposome-encapsulated

prednisolone phosphate inhibits growth of established tumors in

mice. Neoplasia. 7:118–127. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gabizon A and Martin F: Polyethylene

glycol-coated (pegylated) liposomal doxorubicin. Rationale for use

in solid tumours. Drugs. 4 Suppl 54:S15–S21. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Harris L, Batist G, Belt R, Rovira D,

Navari R, Azarnia N, Welles L and Winer E; TLC D-99 Study Group, :

Liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin compared with conventional

doxorubicin in a randomized multicenter trial as first-line therapy

of metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 94:25–36. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hioki A, Wakasugi A, Kawano K, Hattori Y

and Maitani Y: Development of an in vitro drug release assay of

PEGylated liposome using bovine serum albumin and high temperature.

Biol Pharm Bull. 33:1466–1470. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Deshpande PP, Biswas S and Torchilin VP:

Current trends in the use of liposomes for tumor targeting.

Nanomedicine (Lond). 8:1509–1528. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Haley B and Frenkel E: Nanoparticles for

drug delivery in cancer treatment. Urol Oncol. 26:57–64. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cukierman E and Khan DR: The benefits and

challenges associated with the use of drug delivery systems in

cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 80:762–770. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fan Y, Liu J, Wang D, Song X, Hu Y, Zhang

C, Zhao X and Nguyen TL: The preparation optimization and immune

effect of epimedium polysaccharide-propolis flavone liposome.

Carbohydr Polym. 94:24–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhu Y, Wang M, Zhang J, Peng W, Firempong

CK, Deng W, Wang Q, Wang S, Shi F, Yu J, et al: Improved oral

bioavailability of capsaicin via liposomal nanoformulation:

Preparation, in vitro drug release and pharmacokinetics in rats.

Arch Pharm Res. 38:512–521. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pandurangan AK and Esa NM: Luteolin, a

bioflavonoid inhibits colorectal cancer through modulation of

multiple signaling pathways: A review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

15:5501–5508. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang LM, Xie KP, Huo HN, Shang F, Zou W

and Xie MJ: Luteolin inhibits proliferation induced by IGF-1

pathway dependent ERα in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Asian Pac

J Cancer Prev. 13:1431–1437. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Pratheeshkumar P, Son YO, Budhraja A, Wang

X, Ding S, Wang L, Hitron A, Lee JC, Kim D, Divya SP, et al:

Luteolin inhibits human prostate tumor growth by suppressing

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-mediated

angiogenesis. PLoS One. 7:e522792012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Matsumura Y and Maeda H: A new concept for

macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: Mechanism of

tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent

smancs. Cancer Res. 46:6387–6392. 1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Vasey PA, Kaye SB, Morrison R, Twelves C,

Wilson P, Duncan R, Thomson AH, Murray LS, Hilditch TE, Murray T,

et al: Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of PK1

[N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer doxorubicin]: First

member of a new class of chemotherapeutic agents-drug-polymer

conjugates. Cancer research campaign phase I/II committee. Clin

Cancer Res. 5:83–94. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|