Introduction

Glioma is the most common malignant tumor of the

central nervous system in adults. According to the WHO

classification of tumors of the nervous system, glioma may be

further divided into four grades (grades I–IV) with increasing

malignancy (1). Grade IV,

additionally termed glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is the most

malignant type of brain tumor. Despite the improved survival

associated with modern surgical, chemotherapy and radiotherapy

treatments, the prognosis of patients with glioma remains poor due

its rapid and invasive growth, its genetic heterogeneity, and a

lack of understanding of its underlying molecular mechanisms

(2,3).

Vasculogenic mimicry (VM) refers to non-endothelial

tumor cell-lined microvascular channels in aggressive, malignant

and genetically dysregulated tumors (4,5). A

previous report indicated that VM had been implicated in invasion,

metastasis and cancer progression (6). However, there is limited data

regarding the correlation with VM and abnormally-expressed genes in

human gliomas. Aquaporins (AQPs) are a family of water-selective

transmembrane transport channels that allow rapid movement of

H2O across normally hydrophobic cell membranes (7). In previous studies, AQP1 and AQP4

have received the most attention due to their contributions to

brain edema (8,9). In brain tumors, studies have

demonstrated that AQP1 expression is increased with the grade of

malignancy, and was associated with tumor blood vessels (10,11).

However, the role of AQP1 remains speculative in glioma.

In the present study, the AQP1 expression was

measured in clinical glioma tissue samples and GBM cell lines.

Subsequently, short hairpin (shRNA)-mediated AQP1 silencing was

used to assess the potential effects of AQP1 on migration, invasion

and VM formation using two types of GBM cell lines in vitro

and in vivo. The present study aimed to assess the

expression and functional role of aquaporin-1 (AQP1) in human GBM

migration, invasion and VM formation.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples and cell lines

All the clinical glioma tissues samples were

obtained from Guangzhou Overseas Chinese Hospital (Guangzhou,

China) and, according to criteria from the World Health

Organization (WHO), classified into 4 grades with increasing

malignancy: Grade I pilocytic astrocytoma; grade II astrocytoma;

grade III anaplastic astrocytoma; and grade IV GBM, the most

malignant brain tumor. For each grade, 10 cases were used in the

present study. All samples were freshly frozen in liquid nitrogen

and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. The present study was

approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Guangzhou

Overseas Chinese Hospital, and all participants provided written

informed consent. The GBM cell lines A172 and U251, and the normal

glial cell line HEB were obtained from the Shanghai Cell Collection

(Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT,

USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone; GE

Healthcare Life Sciences) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified

atmosphere.

Cell transfection

The shRNA-AQP1 was synthesized and cloned into the

pSUPER-retro-puromycin plasmid (Shangahi GenePharma Co., Ltd.,

Shanghai, China). The shRNA-AQP1 sequence was:

5′-GATCACACACAACTTCAGCAACTCGAGTTGCTGAAGTTGTGTGTGATC-3, and the

negative control sequence was:

5′-CACCGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTCGAAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAA-3′. The plasmids

above were combined with PIK vector, and lentiviral vectors were

constructed. Following 10 h transfection (multiplicity of

infection=20) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's

protocol, the transfected A172 and U251 cells were selected with

puromycin, and the stably transfected cell lines were prepared by

monoclonal screening. Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and western blot analyses were used to

assess the transfection efficiency as detailed below.

RT-qPCR assay

Total RNA was extracted from the tissues and cells

using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian,

China) was used, according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was

performed to detect the expression levels of AQP1 mRNA using the

LightCycler 480 detection system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis,

IN, USA). The thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C (15

sec) and 60°C (30 sec). The primer sequences of AQP1 were: Forward,

5′-TCATCTACGACTTCATCCTGGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGAAGCTCCTGGAGTTGATGT-3′. β-actin mRNA levels were used for

normalization: Forward 5′-GTCCACACCCGCCACCAGTTC-3′ and reverse

5′-TCCCACCATCACACCCTGGTG-3′. The qPCR results were analyzed and

expressed as relative mRNA levels of the Cq value, which was then

converted to a fold change (12).

Western blot analysis

The tissue samples and cells were lysed in a

radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4),

150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40] containing a protease inhibitor cocktail

(Roche Diagnostics), and the protein concentration was measured

using a micro bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A total of 50 µg per lane of the total

cell lysates was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to

polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk for

1 h at room temperature, and followed by immunoblot detection and

visualization with enhanced chemiluminescence western blot

detection reagents (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Immunoblotting was performed with AQP1 antibodies (Abcam,

Cambridge, UK; cat. no. ab15080; 1:1,000) at 37°C for 2 h, followed

by incubation with the horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated

immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies (Abcam; cat. no. ab97023;

1:5,000) for 1 h at room temperature. GAPDH (Abcam; cat. no.

ab8245; 1:1,000) levels were used for the control and

normalization. The protein bands were scanned and quantified using

ChemiDoc MP imaging analysis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

Hercules, CA, USA) as the relative grey value.

Transwell migration and invasion

assay

The transfected A172 and U251 cells were trypsinized

and resuspended to a density of 5×105 cells/ml in

serum-free medium. A total of 200 µl cell suspension was added to

the upper chamber of each well in 24-well polycarbonate Transwell

membrane inserts (BD, 353097, USA) coated with 40 µl extracellular

matrix (ECM) Matrigel (invasion assay; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany) or without Matrigel (migration assay), and 600

µl Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum was added in the lower chamber. Following incubation

for 24–48 h at 37°C, cells on the upper membrane surface were

removed by careful wiping with a cotton swab, and the Transwells

were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min at room

temperature and stained with 0.2% crystal violet solution for 30

min at room temperature. Migrated and invaded cells adhering to the

underside of the Transwell were counted using an inverted

microscope (magnification, ×400).

VM assay

A total of 50 µl ECM Matrigel (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) was dropped onto 18-mm glass coverslips in 6-well plates and

incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the transfected A172 and

U251 cells (2×105 cells/well) were seeded onto the

coated coverslips. Following incubation for 24–48 h, the cells were

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 10 min at room temperature,

oxidized in a 0.5% periodic acid solution for 5 min and rinsed with

PBS. The coverslips were dried at room temperature and the VM

images were captured at ×400 magnification (CX71, Olympus

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

In vivo xenograft experiments

A total of 6 female BALB/C nude mice (weight, 20–22

g) at the age of 4 weeks were obtained from the Laboratory Animal

Centre of Jinan University (Guangzhou, China). The animals were

maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle under room temperature

(24±1°C) and humidity of 50±10%, and free fed with standard forage

and clean water. They were randomly divided into two groups (three

mice per group). The silenced A172 cell and negative control cell

suspensions (5×106 cells/ml) in 200 µl serum-free medium

were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of nude mice. Tumor

growth was measured twice per week for 4–5 weeks. Following 5

weeks, tumor samples were carefully isolated, weighed and analyzed

by hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. The experimental protocol was

approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Jinan

University (Guangzhou, China).

Invasion-associated protein

measurement and HE staining

The isolated tumor tissues were divided into two

parts: One for the measurement of the invasion-associated proteins

αvβ3 integrin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; cat. no. ab78289; dilution,

1:500), 72 kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-2; Abcam; cat. no. ab37150;

dilution, 1:500) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9; Abcam; cat.

no. ab38898; dilution, 1;1,000) using western blot analysis as

aforementioned; and the other for HE staining.

The tissues were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS

solution for 30 min at room temperature, and sliced into 3–5 µm

sections following paraffin-embedding. Slides were stained as

follows: 70% ethyl alcohol for 10 sec; diethylpyrocarbonate-treated

water for 5 sec; hematoxylin with RNAase inhibitor for 20 sec; 70%

ethyl alcohol for 30 sec; eosin Y in 100% ethyl alcohol for 20 sec

followed by dehydration with a series of alcohols for 30 sec each;

and xylene for 2 min.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of

variance and data from the multiple groups were also analyzed using

analysis of variance with repeated measures. The Student's t-test

to determine statistical significance using SPSS 17.0 statistical

software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). In addition, the least

significant difference post-hoc test was employed where equal

variances were assumed, while Dunnett's T3 test used when equal

variances were not assumed. The results are expressed as the mean ±

standard deviation with at least three times. Two-tailed P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

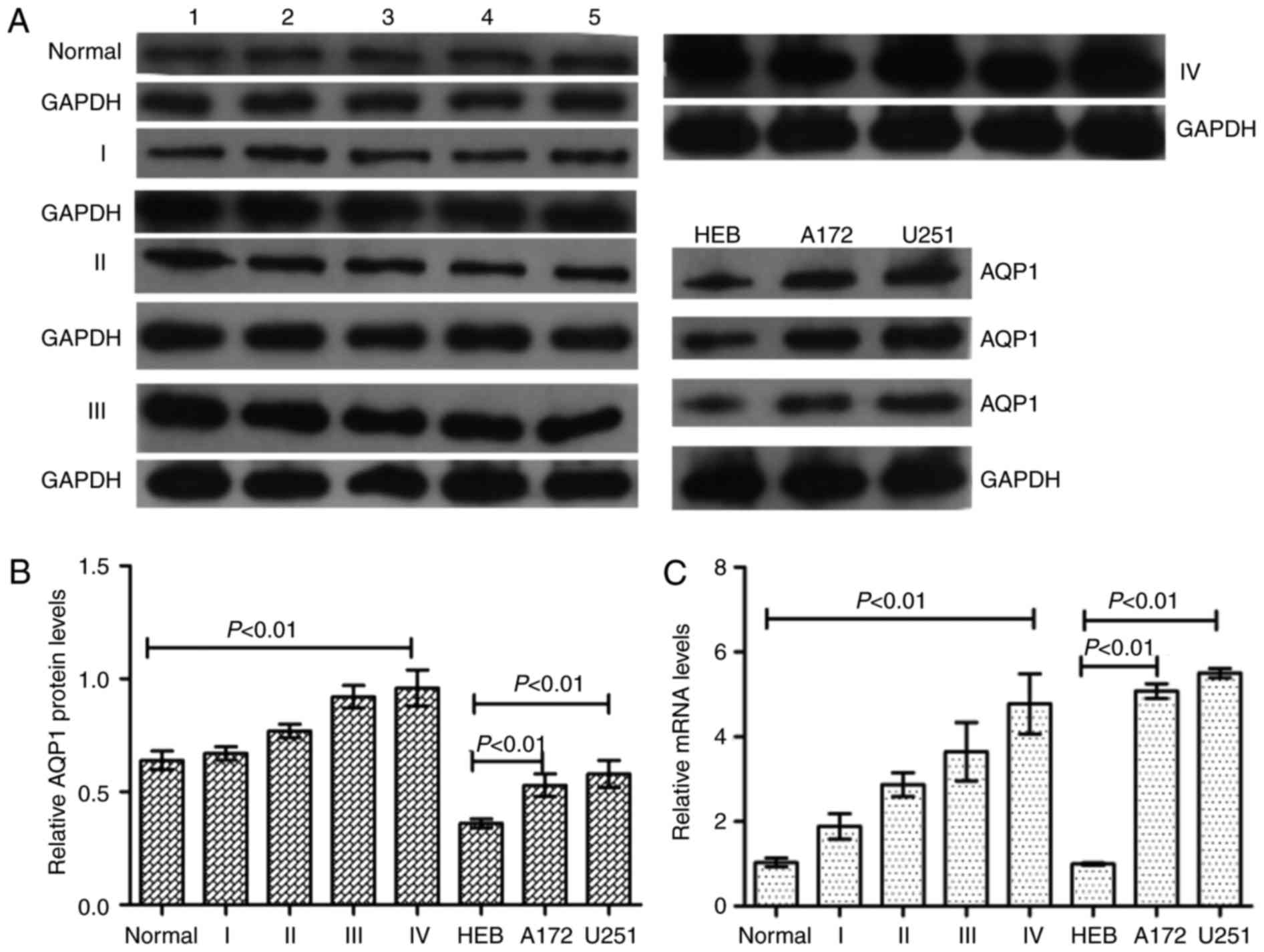

AQP1 is upregulated in glioma tissues

and cell lines, and is associated with malignancy grade

The expression of AQP1 in normal brain tissues,

glioma tumor tissues and glioma cell lines was analyzed by western

blotting and RT-qPCR analysis. Western blotting and RT-qPCR

analysis demonstrated that AQP1 was expressed at higher levels in

glioma tumor tissues and cell lines compared with normal brain

tissues and HEB cells, and was positively associated with glioma

malignancy (glioma grades; Fig.

1), meaning that a higher malignant grade of glioma was

associated with a higher AQP1 expression level.

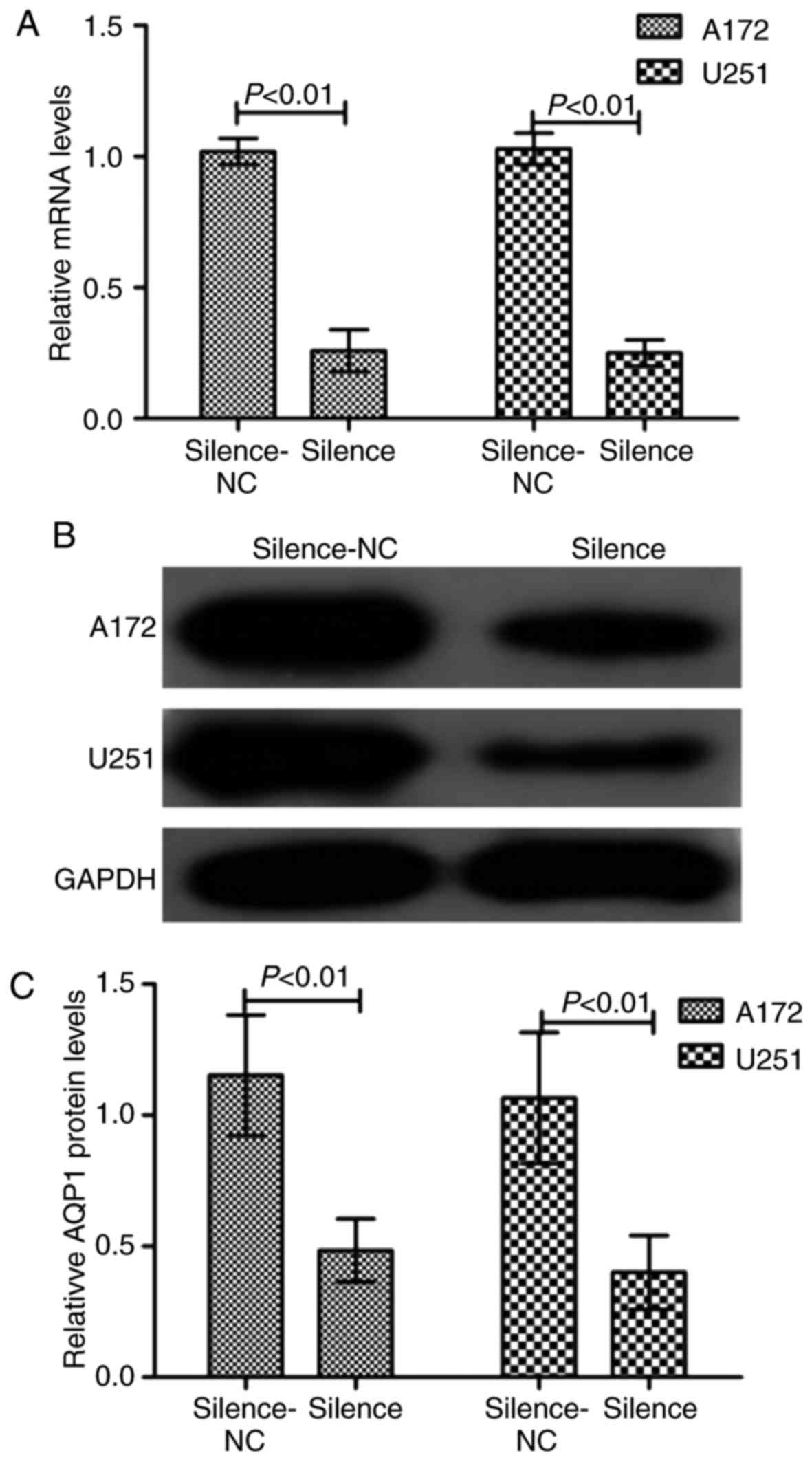

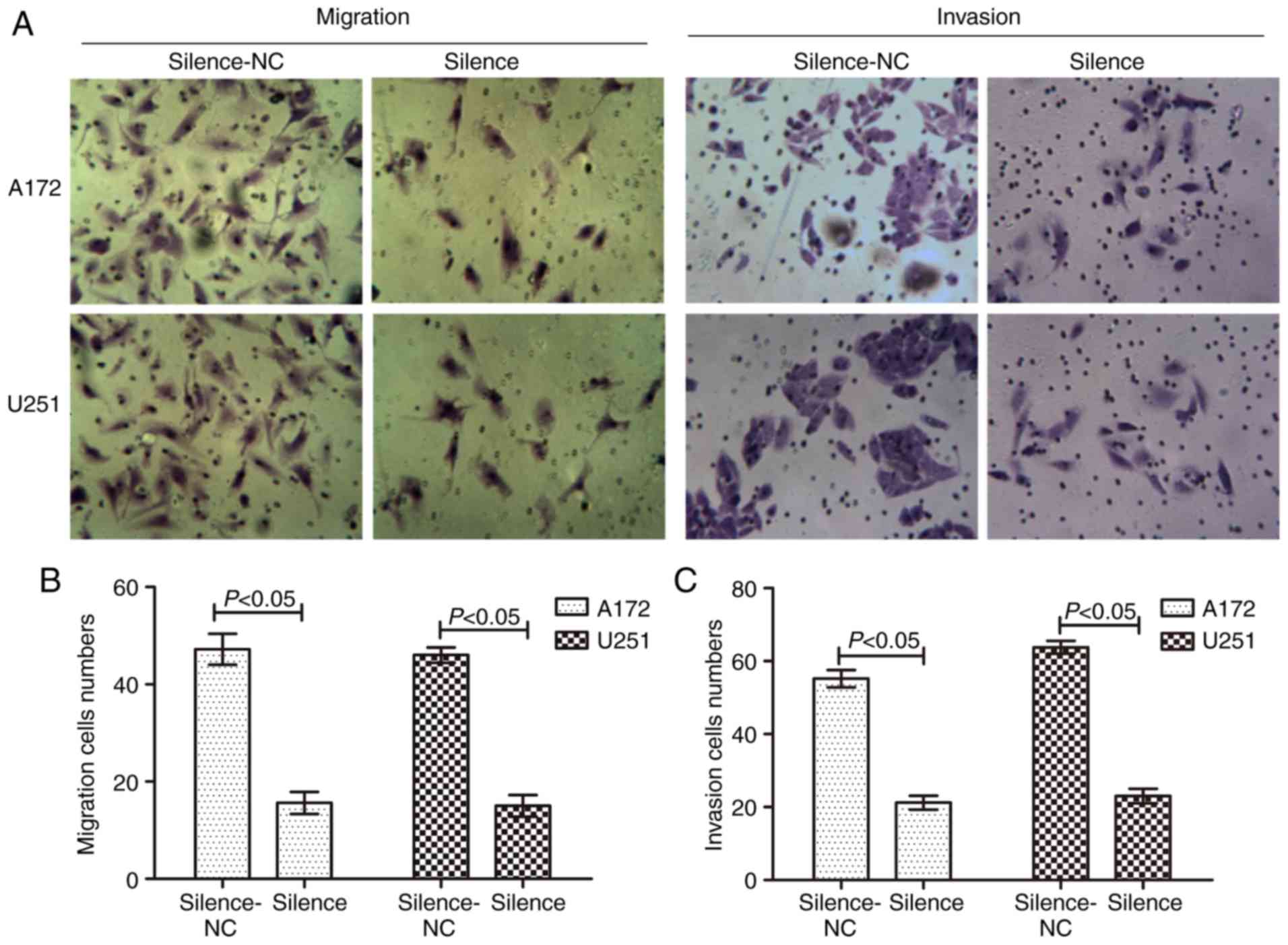

Silencing of AQP1 inhibits GBM

migration and invasion

To examine the role of AQP1 in glioma cells, AQP1

was stably silenced using shRNA-AQP1 in A172 and U251 cells. As

presented in Fig. 2, RT-qPCR

analysis and western blotting demonstrated that the transfection

was successful in reducing the expression levels of AQP1. Following

transfection, a Transwell assay demonstrated that the migratory and

invasive capacity were markedly reduced in the silenced group,

demonstrating that the number of migrated and invaded cells

decreased (Fig. 3). There was a

statistical difference between the NC and transfected groups

(P<0.05). These results suggested that silencing of AQP1 reduced

the abilities of migration and invasion in GBM cells.

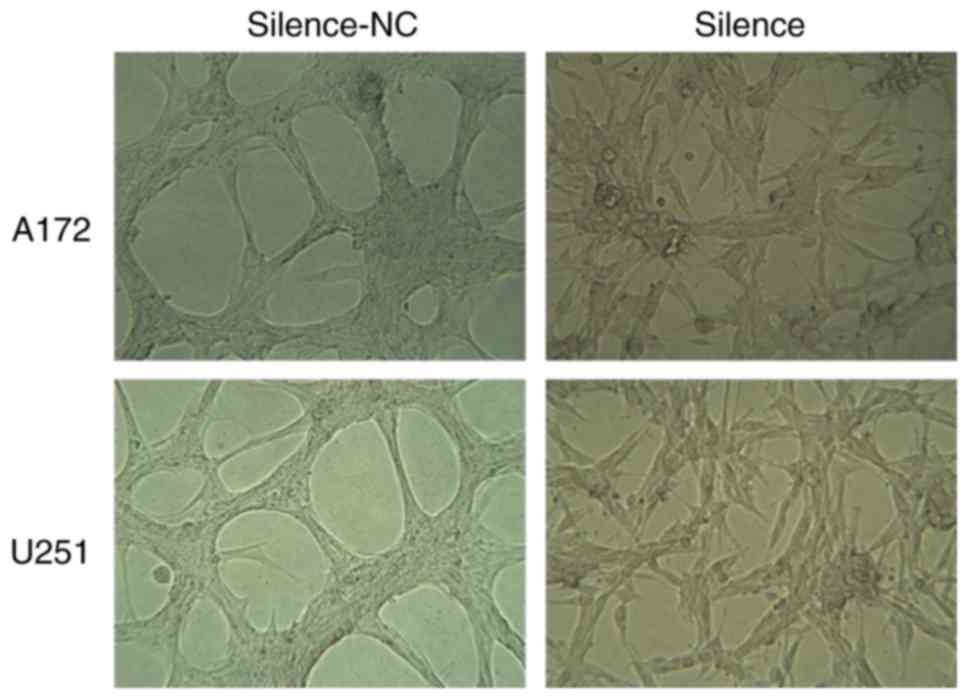

Silencing of AQP1 inhibits the

development of VM in vitro

VM is associated with tumor blood supply and

metastasis. The number of vessels (nodes) and the remodeling of the

microcirculation are used as histological markers of tumor

progression. In in vitro experiments, the vessel numbers of

the network channels, which reflect VM development, were calculated

and analyzed. It was observed that A172 and U251 cells in the

silence-NC group, which express high levels of AQP1, formed

classical VM networks on Matrigel. Following silencing of AQP1 via

transfection, it was observed that the classical VM networks became

less obvious, and the number of vessels decreased significantly in

the silence group, compared with the silence-NC group (Fig. 4). These results suggested that AQP1

may regulate the development of VM in GBM cells in

vitro.

Silencing of AQP1 inhibits

tumorigenesis and induces invasion-associated protein

expression

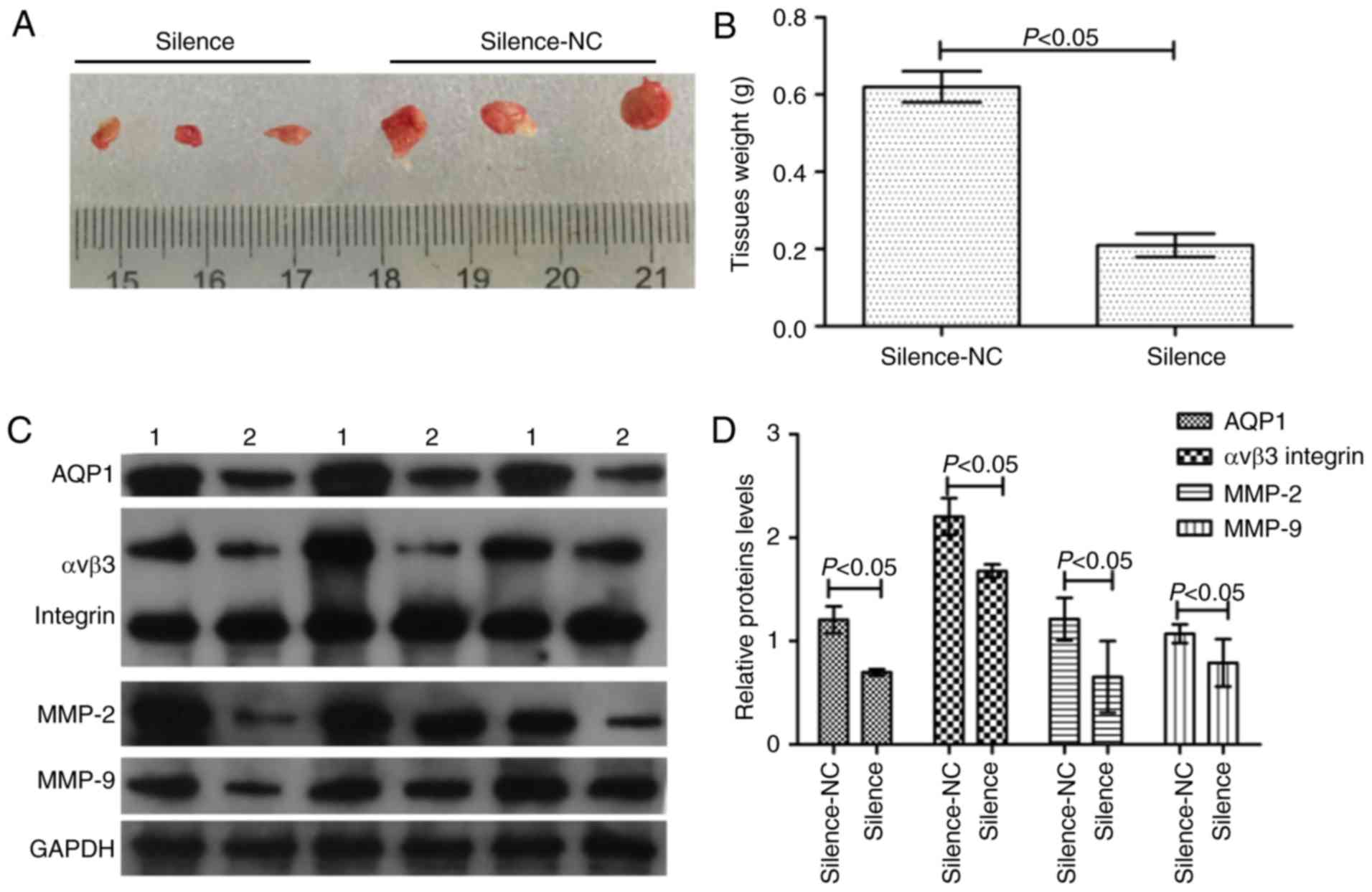

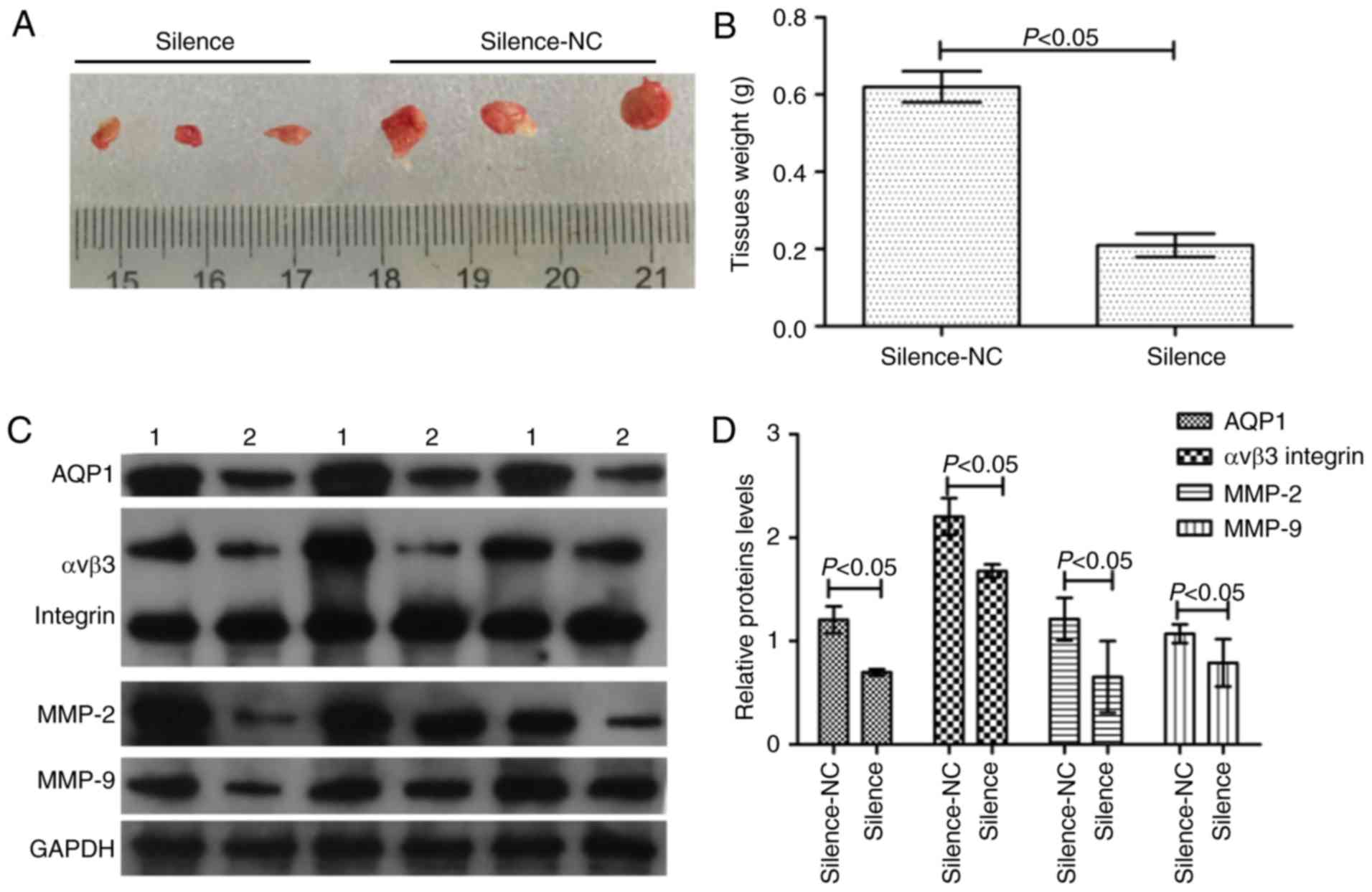

In order to study the effect of AQP1 on

tumorigenesis and tumor infiltration in vivo, the

transfected A172 and U251 cells were planted into the nude mouse

xenograft model. Across the 35 days, there was a marked decrease in

tumor weight in the silence group compared with the silence-NC

group (Fig. 5A and B). In

addition, western blot analysis of invasion-associated proteins

demonstrated that in the case of decreased AQP1 expression, the

expression of αvβ3 integrin, MMP-2 and MMP-9 in the silence group

decreased (Fig. 5C and D). There

were statistical differences between the silence-NC group and the

silence group (P<0.05). These results suggested that silencing

of AQP1 reduced the abilities of tumorigenesis and tumor

infiltration in vivo.

| Figure 5.AQP1 regulates tumorigenesis in

vivo. (A) Macroscopic appearance of xenotransplanted tumors.

(B) Quantitative analysis of tumor weights. (C) The western

blotting images of AQP1, αvβ3 integrin, MMP-2, MMP-9 protein. 1,

Silence-NC group; 2, silence group. (D) Gray scale analysis of

relative AQP1, αvβ3 integrin, MMP-2, MMP-9 expression levels in the

western blotting. Values are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. n=3. AQP1, aquaporin-1; MMP-2, 72 kDa type IV

collagenase; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; NC, negative

control. |

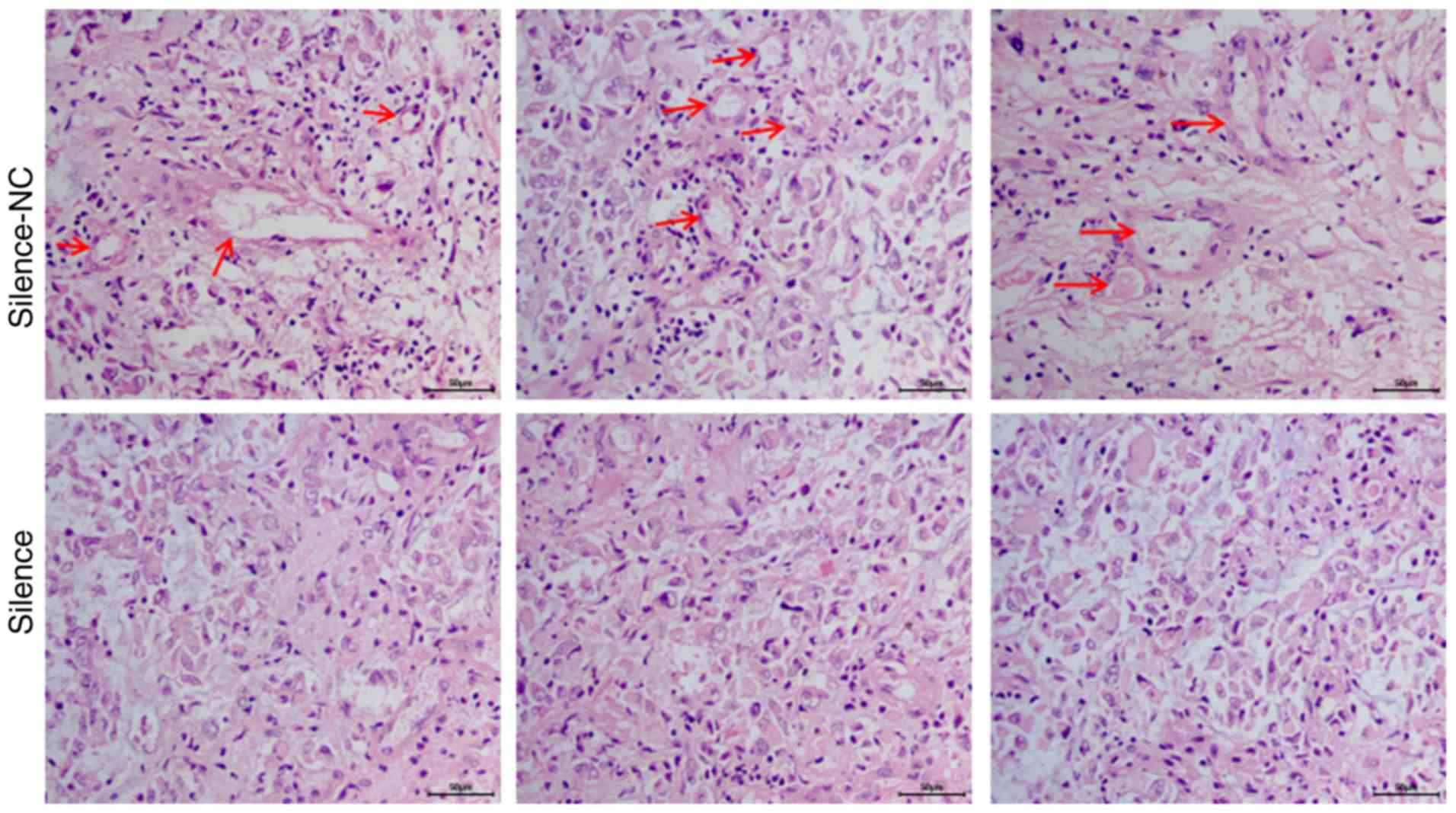

Silencing of AQP1 inhibited the

development of VM in vivo

In vivo, cancer tissues require an adequate

blood supply for growth, and VM serves as an alternative pathway

for maintaining this supply. In the in vivo experiment, VM

was analyzed using the in vivo xenograft tumors via HE

staining. HE staining demonstrated that A172 cells in the

silence-NC group formed a large number of typical vascular

structures (red arrows; Fig. 6).

Following silencing of AQP1 via transfection, the number of

vascular structures decreased significantly in the silence group,

compared with the silence-NC group. These results suggested that

AQP1 may regulate the development of VM in vivo.

Discussion

Using western blotting and RT-qPCR, the present

study demonstrated that AQP1 expression levels were upregulated and

positively associated with glioma grade, and that the highest

expression levels were observed in GBM cells. Based on the

characteristics of malignant glioma and this observation, it was

hypothesized that AQP1 may be associated with GBM migration and

invasion. In addition, a previous report revealed that AQP1

regulated cell volume via the rapid transmembrane transport of

water, thereby promoting cell migration (13). In a study into the metastasis of

lung cancer, the researchers reported that AQP1 led to

extravasation and spread (14).

In order to verify the above hypothesis,

shRNA-mediated AQP1 silencing was used to assess the potential

effects of AQP1 on migration and invasion using two types of GBM

cell line. The Transwell assay demonstrated that silencing of AQP1

was able to suppress GBM cell migration and invasion in

vitro. In angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis, MMPs

(including MMP-2 and MMP-9) and integrins (including αvβ3) degrade

the ECM and release and/or activate growth factors, finally

resulting in cancer cell migration and invasion (15,16).

Previous reports demonstrated that elevated αvβ3 integrin, MMP-2

and MMP-9 expression levels in tumor cells markedly increased the

adhesion and migration of the tumor cells (17–20).

In the present study, western blot analysis using in vivo

xenograft tumor tissues demonstrated that invasion-associated

protein (αvβ3 integrin, MMP-2 and MMP-9) expression decreased in

the AQP1 silence group, indicating that silencing of AQP1 was able

to suppress GBM migration and invasion in vivo.

Additionally, AQP1 knockdown or inhibition may effectively inhibit

cell proliferation, invasion and tumorigenesis in osteosarcoma and

hepatocellular carcinoma (21,22).

From the above data, it was inferred that AQP1 was indeed

associated with GBM migration and invasion, and that silencing of

AQP1 was able to suppress GBM migration and invasion, in

vitro and in vivo.

Inhibiting angiogenesis is an important therapeutic

approach in cancer (23,24). The proteins that regulate abnormal

angiogenesis have attracted intense interest. AQP1, as a water

channel membrane protein, was able to promote tumor angiogenesis by

allowing faster endothelial cell migration in a mouse model of

melanoma (25,26). In human glioma, it was demonstrated

that elevated AQP1 in GBM cells led to a typical angiogenesis

structure, and that AQP1 knockdown reduced VM structure formation

in vitro. In vivo, VM channels are patterned networks

with red blood cells readily detectable inside such channels, and

are arranged in arcs, loops and networks (27). In the present in vivo

xenograft experiment, HE staining exhibited typical VM channels in

GBM cells and, following AQP1 silencing, the number of typical VM

channels decreased. These results demonstrated that VM formation

may be inhibited by regulating AQP1 expression in human GBM.

In conclusion, AQP1 was positively associated with

glioma grade and promoted glioma cell migration, invasion and VM

formation in vitro and in vivo. In the treatment of

malignant glioma, the present study may provide a strategy and

facilitate the development of AQP1-directed diagnostics and

therapeutics against glioma. Further studies ought to be aimed at

performing a systematic evaluation of AQP1 in gliomas of different

grades, and correlating such findings with clinical survival

parameters.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Scientific

Research and Cultivation of Special Fund of the First Clinical

Medical College of Jinan University (grant no. 2015109).

References

|

1

|

Kleihues P, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW,

Rorke LB, Reifenberger G, Burger PC and Cavenee WK: The WHO

classification of tumors of the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp

Neurol. 61:215–225. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Stupp R, van den Bent MJ and Hegi ME:

Optimal role of temozolomide in the treatment of malignant gliomas.

Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 5:198–206. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Anderson HJ and Galileo DS: Small-molecule

inhibitors of FGFR, integrins and FAK selectively decrease

L1CAM-stimulated glioblastoma cell motility and proliferation. Cell

Oncol (Dordr). 39:229–242. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

El Hallani S, Boisselier B, Peglion F,

Rousseau A, Colin C, Idbaih A, Marie Y, Mokhtari K, Thomas JL,

Eichmann A, et al: A new alternative mechanism in glioblastoma

vascularization: Tubular vasculogenic mimicry. Brain. 133:973–982.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Folberg R, Hendrix MJ and Maniotis AJ:

Vasculogenic mimicry and tumor angiogenesis. Am J Pathol.

156:361–381. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Guzman G, Cotler SJ, Lin AY, Maniotis AJ

and Folberg R: A pilot study of vasculogenic mimicry

immunohistochemical expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch

Pathol Lab Med. 131:1776–1781. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

King LS, Yasui M and Agre P: Aquaporins in

health and disease. Mol Med Today. 6:60–65. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mohammadi MT and Dehghani GA: Nitric oxide

as a regulatory factor for aquaporin-1 and 4 gene expression

following brain ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat. Pathol Res

Pract. 211:43–49. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yao X, Derugin N, Manley GT and Verkman

AS: Reduced brain edema and infarct volume in aquaporin-4 deficient

mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett.

584:368–372. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Hara-Chikuma M

and Verkman AS: Impairment of angiogenesis and cell migration by

targeted aquaporin-1 gene disruption. Nature. 434:786–792. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Oshio K, Binder DK, Liang Y, Bollen A,

Feuerstein B, Berger MS and Manley GT: Expression of the

aquaporin-1 water channel in human glial tumors. Neurosurgery.

56:375–381. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rouzaire-Dubois B, Ouanounou G and Dubois

JM: Relationship between extracellular osmolarity, NaCl

concentration and cell volume in rat glioma cells. Gen Physiol

Biophys. 30:162–166. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xie Y, Wen X, Jiang Z, Fu HQ, Han H and

Dai L: Aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 4 are involved in invasion of lung

cancer cells. Clin Lab. 58:75–80. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Klein G, Vellenga E, Fraaije MW, Kamps WA

and de Bont ES: The possible role of matrix metalloproteinase

(MMP)-2 and MMP-9 in cancer, eg acute leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 50:87–100. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Roy R, Yang J and Moses MA: Matrix

metalloproteinases as novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic

targets in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:5287–5297. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jiao Y, Feng X, Zhan Y, Wang R, Zheng S,

Liu W and Zeng X: Matrix metalloproteinase-2 promotes αvβ3

integrin-mediated adhesion and migration of human melanoma cells by

cleaving fibronectin. PLoS One. 7:e415912012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Brooks PC, Clark RA and Cheresh DA:

Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis.

Science. 264:569–571. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kuphal S, Bauer R and Bosserhoff AK:

Integrin signaling in malignant melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

24:195–222. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bauvois B: New facets of matrix

metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 as cell surface transducers:

Outside-in signaling and relationship to tumor progression. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1825:29–36. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wu Z, Li S, Liu J, Shi Y, Wang J, Chen D,

Luo L, Qian Y, Huang X and Wang H: RNAi-mediated silencing of AQP1

expression inhibited the proliferation, invasion and tumorigenesis

of osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 16:1332–1340. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pelagalli A, Nardelli A, Fontanella R and

Zannetti A: Inhibition of AQP1 hampers osteosarcoma and

hepatocellular carcinoma progression mediated by bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 17:E11022016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu XM, Zhang QP, Mu YG, Zhang XH, Sai K,

Pang JC, Ng HK and Chen ZP: Clinical significance of vasculogenic

mimicry in human gliomas. J Neurooncol. 105:173–179. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kirschmann DA, Seftor EA, Hardy KM, Seftor

RE and Hendrix MJ: Molecular pathways: Vasculogenic mimicry in

tumor cells: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin Cancer

Res. 18:2726–2732. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Nicchia GP, Stigliano C, Sparaneo A, Rossi

A, Frigeri A and Svelto M: Inhibition of aquaporin-1 dependent

angiogenesis impairs tumour growth in a mouse model of melanoma. J

Mol Med(Berl). 91:613–623. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Hara-Chikuma M

and Verkman AS: Impairment of angiogenesis and cell migration by

targeted aquaporin-1 gene disruption. Nature. 434:786–792. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yue WY and Chen ZP: Does vasculogenic

mimicry exist in astrocytoma? J Histochem Cytochem. 53:997–1002.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|