Introduction

Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) has been

widely used in cardiovascular surgery since its introduction by

Griepp et al in 1975 (1).

Despite its effectiveness in reducing mortality, prolonged DHCA

(>40 min) inevitably leads to neuropsychopathic complications

(2), such as temporary or

permanent neurological dysfunction, which has a remarkable

influence on prognosis. A number of experiments have revealed that

disruption to the blood brain barrier (BBB) is probably a vital

aspect in cerebral damage. The BBB is composed of endothelial cells

and functions to create a ‘protective bubble’ around the brain. The

BBB transendothelial electrical resistance induced by tight

junction (TJ) impedes paracellular transport and maintains cell

polarity (3,4).

TJ complexes comprise various transmembrane

proteins, including occludin, claudins, junctional adhesion

molecules and cytoplasmic plaque proteins, such as zona occludens

protein (ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3) (5,6). The

first TJ protein identified in endothelial cells, occludin,

interacts with ZO-1 in the cytoplasm. ZO-1 protein has shown to be

closely related to α-catenin and the actin cytoskeleton (7). A previous study suggested that

occludin-knockout treatments may significantly promote endothelial

barrier permeability (8).

Occludin-knockout mice exhibit normal TJ morphology and intestinal

epithelial barrier function (9).

Another study reported that low occludin expression levels had no

influence on either the organization or the function of TJs

(10). Therefore, it is speculated

that TJ proteins are potential signaling molecules. Occludin and

claudin proteins contain several phosphorylation sites, which have

been indicated to increase protein internalization (11). Therefore, phosphorylation treatment

may promote BBB leakiness. Notably, these phosphorylation sites are

located in the consensus sequences of protein kinase (PK)C and PKA

(12), both of which are involved

in occludin phosphorylation under normal and hypoxic conditions.

PKC is a family of protein kinases that are involved in controlling

the function of several other proteins through the phosphorylation

of hydroxyl groups on the serine and threonine amino acid residues

(13). PKC is activated by signals

such as increased concentrations of dystroglycan (DAG) or cytosolic

calcium ions (Ca2+) (14). The PKC family comprises classical,

novel and atypical isoforms. Classical PKCs, including PKCα,

PKC-βI, PKC-βII and PKC-γ, require Ca2+, DAG and a

phospholipid, such as phosphatidyl serine, for activation (15,16).

TLRs are a family of receptors that monitor the

presence of pathogens by their ability to identify microbial

structural patterns. A previous study reported that bronchial

epithelial cells express functional TLRs 1–6 and TLR9 (17). Atypical protein kinase C has been

implicated in the regulation of the assembly of tight junctions in

polarized epithelial cells (18)

and previous studies have also identified signaling associations

between TLR4 and PKC (19,20). For example, knockout treated TLR4

effectively decreased PKC-ζ expression and remitted liver damage in

a study of acute pancreatitis (21). Meanwhile, PKC has also been shown

to increase expression of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which suggests

that TLR4 activity is PKC-dependent (19). TLR4 is important in maintaining the

enteric immune balance. Low expression of TLR4 and its downstream

factor MyD88 exerts a protective effect on the whole immunologic

balance (22). However, the

overexpression of TLR4 is generally thought to serve a role in the

activation of PKC and the induction of a series of inflammatory

disorders (23,24).

Previous studies have reported that toll-like

receptor 4 (TLR4) activates nonspecific PKC (19,21),

which in turn accelerates the mobilization of TLR4 to lipid rafts.

In addition, hypoxia-induced changes to the BBB involve increased

paracellular permeability through a PKC activity-dependent

mechanism, as demonstrated in both in vitro and in

vivo conditions (25). Brain

microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC), the major component of the

blood-brain barrier, limit the passage of soluble and cellular

substances from BBB. BMECs highly express genes associated with TJ

molecules and efflux/influx transporters, and thereby could

regulate the entrance of various types of compounds such as small

molecules and drugs, into the brain. Therefore, BMECs have been

proved to serve a critical role in the pathogenesis of many brain

diseases (26). Based on the

results mentioned above, we hypothesized that the

TLR4/PKCα/occludin signaling pathway may be related with BMECs.

Therefore, the relationships between PKCα and BMECs were

investigated using a knockdown system. The mRNA expression and

protein expression in different groups were tested. The results had

identified our assumption that TLR4/PKCα/occludin signaling is

closely related with BBB damage. This study may aid in advancing

our understanding of the role of PKCα in the development of BBB

damage.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

All experiments were performed according to the

relevant guidelines published by the Ministry of Agriculture of

China. All protocols were approved by the Institute of Animal

Sciences at the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical

University (Ganzhou, China), where the experiments were conducted.

Primary cultures of rat BMECs were collected from Wistar rats (aged

2 weeks) obtained from Sun Yat-sen University Experimental Animal

Center (Guangzhou, China). Six male rats were housed in a

pathogen-free facility with 12 h light/dark cycles and free access

to food and water, and were acclimated for 1 week before

experiments. The rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and

whole brains were quickly removed. After removing cerebellum,

diencephalon (including hippocampus), white matter, residual

vessels and cerebral pia mater, the cerebral cortex were washed

with D-Hanks solution for three times. Then the cerebral cortex was

cut into pieces by iris scissors and incubated with 0.1% II

collagenase at 37°C for 1.5 h. The supernatant was discarded,

bovine serum albumin added and the sample centrifuged for 8 min at

4°C (1,000 × g) to remove upper nervous tissue. It was then

centrifuged again at 1,000 × g for 8 min at room temperature prior

to being incubated with II collagenase for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, 2

ml DMEM and 12 ml 50% Percoll were added and centrifuged at 1,000 ×

g for 10 min at 4°C. The yellow layer was the purified BMECs. BMECs

were maintained in a humidified chamber at 5% CO2 and

37°C.

According to the PKCα sequence from GeneBank

(accession no. 002737), three small interference RNA sequences

targeting PKCα were designed: siPKCα-1, 5′-GCGACATGAATGTTCACAA-3′;

siPKCα-2, 5′-GGAAGCAGCCATCTAACAA-3′; and siPKCα-3,

5′-GCTGGTCATCGCTAACATA-3′. These sequences were synthesized in Gene

Pharma, Inc. (Shanghai, China) and used to build a PKCα-knockdown

system according to previous protocol (27). The Control group comprised

untreated BMECs. All lentiviral particles were generated by

following a standardized protocol using the highly purified

plasmids, EndoFectin-Lenti and TiterBoost reagents (Guangzhou

FulenGen Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). The lentiviral transfer

vector was co-transfected into cells with the Lenti-PacHIV

packaging mix (Guangzhou FulenGen Co., Ltd.). The

lentivirus-containing supernatant was harvested 48 h

post-transfection and stored at −80°C.

Cells (5×105 cells/well) were seeded in

6-well plates with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing

10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) without

penicillin and streptomycin overnight at 37°C). Transfection was

carried out with OPTI-MEM serum-free medium and

Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), to achieve a final siRNA concentration of 100 nM

(37°C) (28). In addition, the

TLR4 inhibitor TAK-242 (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., Tokyo,

Japan) was used to treat BMECs at concentrations recommended by a

previous study (29).

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

analysis

The cells were seeded at a density of

1×106 cells/well in 6-well plates. Total RNA was

isolated from 1×106 BMECs with the RNeasy Minikit

(Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's

protocol with the DNase step. RNA (1 µg) was used for cDNA

synthesis using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). mRNA transcript levels were

quantify using the SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and a 96-channel iCycler Optical

system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The SYBR-Green-based reaction

of 25 µl contained SYBR-Green Master Mix (1X), a gene-specific

primer set (forward and reverse primers; 2.5 µM each), cDNA (20

ng), fluorescein calibration dye (10 nM; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.) and ddH2O. Each reaction was performed in

triplicate. The primer sets for PKCα-siRNA-1, PKCα-siRNA-2,

PKCα-siRNA-3, TLR4, occludin, and PKCα (mice species) were

purchased from Genewiz, Inc. (Suzhou, China) and had the following

sequences: PKCα-siRNA-1 forward, 5′-GCGACATGAATGTTCACAA-3′ and

reverse, 5′-TTGTGAACATTCATGTCGC-3′; PKCα-siRNA-2 forward,

5′-GGAAGCAGCCATCTAACAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGTTAGATGGCTGCTTCC-3′;

PKCα-siRNA-3 forward, 5′-GCTGGTCATCGCTAACATA-3′ and reverse,

5′-TATGTTAGCGATGACCAGC-3′; and β-actin forward,

5′-CAGGGCGTGATGGTGGGCA-3′ and reverse,

5′-CAAACATCATCTGGGTCATCTTCTC-3′ was used as the internal control.

The cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 45 sec. The

iCyclerMyiQ software version 5.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was

used to analyze the real-time fluorescence signals. mRNA expression

levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method and

normalized to the β-actin gene (30).

Western blot analysis

Total cellular proteins were extracted from

1×106 BMECs under different treatments using

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1%), radio immunoprecipitation assay

lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Nonidet P-40;

0.1% SDS). Thirty µg proteins (24 g/µl) were boiled with SDS-PAGE

sample buffer for 5 min at 100°C and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The

proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidenedifluoride membrane

(EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5%

fat free milk powder for 1 h at room temperature, followed by

incubation with the following primary antibodies: Rabbit polyclonal

anti-GAPDH (cat. no. ab9485; 1:2,500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA),

rabbit polyclonal anti-PKCα (cat. no. BA1355; 1:400; Boster

Biological Technology, Wuhan, China), rabbit polyclonal anti-TLR4

H-80 (cat. no. sc-10741; 1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.,

Dallas, TX, USA) and rabbit polyclonal anti-occludin (cat. no.

A2601; 1:1,000; Abgent, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight.

The membranes were incubated with the paired secondary antibody

[ProteinFind goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), HRP Conjugate, cat. no.

HS101; 1:1,000; TransGen Biotech, Inc., Beijing, China] for 1 h at

room temperature, and the separated proteins were detected with an

Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection kit (Advansta, Inc., Menlo

Park, CA, USA). The bands were viewed with GeneGnome 5 (Synoptics,

Ltd., Cambridge, UK) and ImageJ version 1.6.0 (National Institutes

of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used for densitometry.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence cell labeling was performed by

rinsing 1×105 cells with cold PBS (pH 7.4; PAN-Biotech

GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany), followed by fixing onto slides for 10

min in cold methanol at −20°C, washing with PBS and incubating with

the mouse anti-occludin primary antibody (cat. no. 33-1500;

dilution, 2.5 µg/ml; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

for 1 h at room temperature. This was followed by an additional

washing step with PBS, incubation with the Cy3-conjugated

anti-mouse antibody (1:300; Jackson Laboratory, Ben Harbor, ME,

USA) for 30 min at 37°C, washing with PBS and mounted using

Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Servion, Switzerland).

Images were captured using a Zeiss 510 Meta confocal laser scanning

microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany); 5 fields per slide

were selected for calculating the intensity. ImageJ (version 1.6.0;

National Institutes of Health) was used for intensity analysis.

Endothelial permeability assay

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran (1

mg/ml; molecular mass, 40 kDa; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany) was used to measure the endothelial

permeability through the BMEC monolayer. To measure paracellular

permeability, around 3×105 BMECs were seeded on

Transwell inserts (pore size, 0.4 µm; Corning, Cambridge, MA, USA)

and cultivated for 2–4 days until a postconfluent cell monolayer

was formed. EBM-2 medium with 0.2% FBS (CC-3156; Lonza, USA) was

used in the upper and lower chambers. Following 30 min of treatment

with 200 µg/ml FITC-coupled dextrans at room temperature, 100 µl

culture medium was collected from the lower compartment and

fluorescence was evaluated using a Paradigm Multi-Mode Plate Reader

(Molecular Devices Shanghai Ltd., Shanghai, China), following the

manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation.

Student's t-test was used to compare the gene relative expression,

relative fluorescence density and FITC intensity with different

treatments. If more than two groups were compared, one-way analysis

of variance was performed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. All experiments were repeated

at least three times.

Results

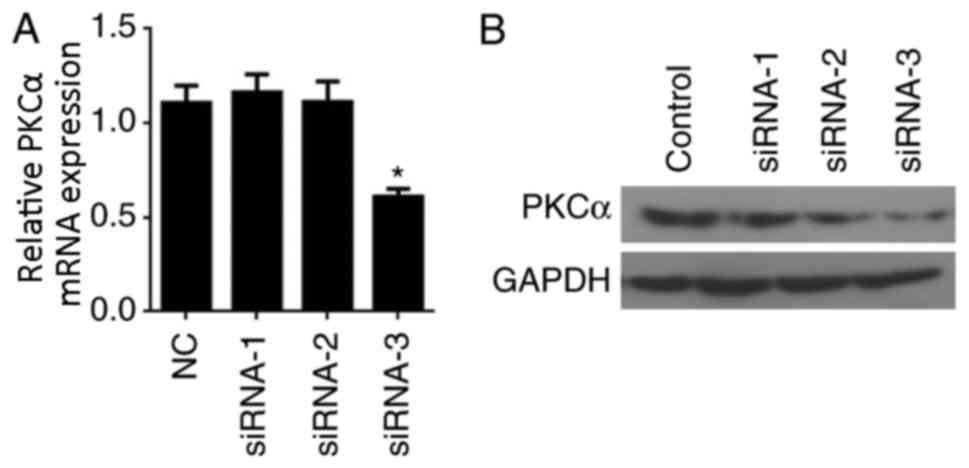

PKCα-knockdown in BMECs

To knockdown PKCα gene expression in BMECs, three

different siRNAs directed against PKCα, designated siRNA-1, siRNA-2

and siRNA-3, were designed and to transfected into BMECs. The

effects of siRNA transfection on PKCα mRNA and protein expression

levels were examined by RT-qPCR and western blot analyses,

respectively. RT-qPCR results indicated that siRNA-3 effectively

reduced PKCα expression (P<0.05 vs. Control; Fig. 1A). Similarly, PKCα protein

expression was notably reduced in cells transfected with siRNA-3

compared with expression in the Control, siRNA-1 and siRNA-2 groups

(Fig. 1B). Therefore, siRNA-3 was

used in all subsequent experiments.

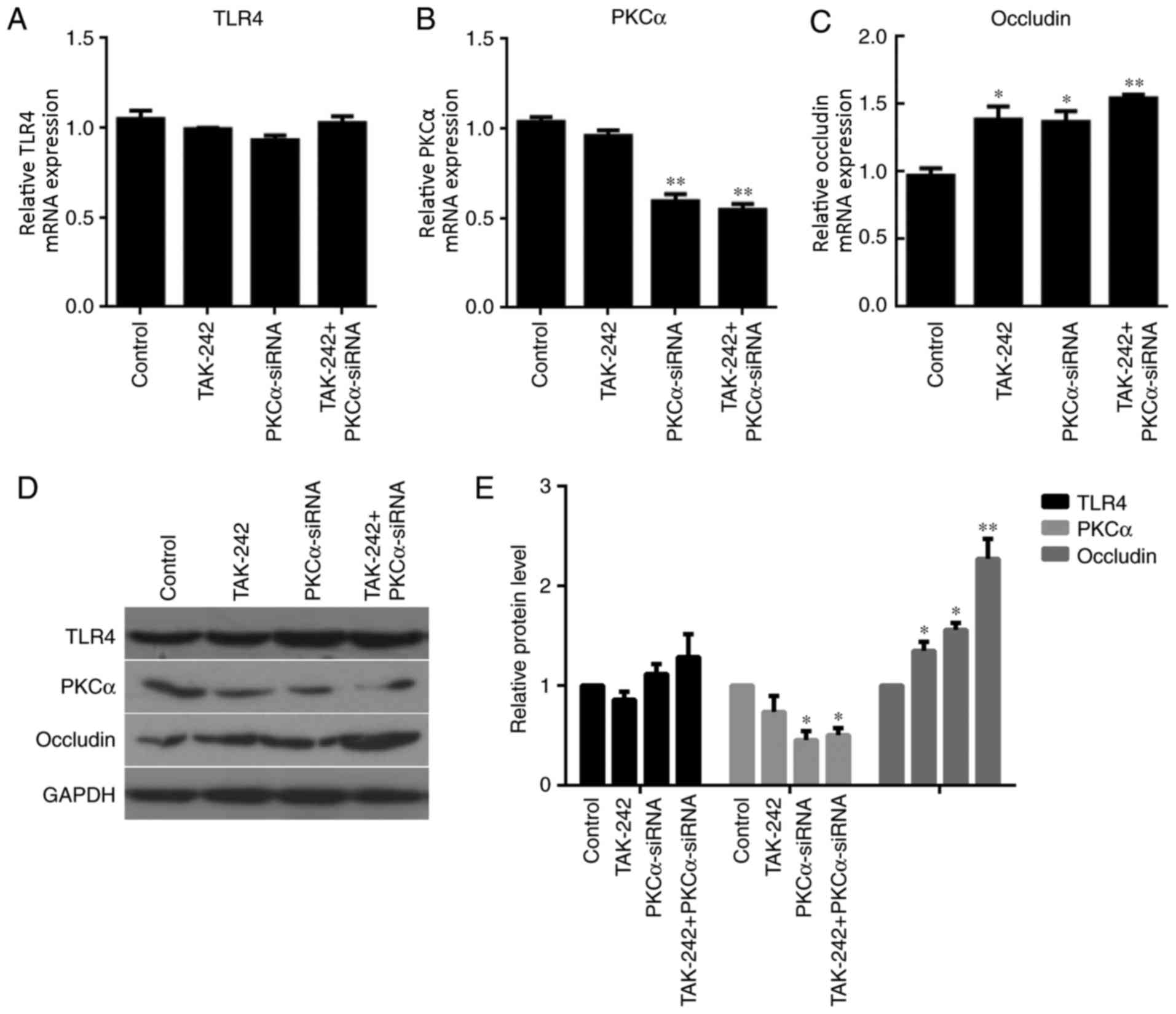

TLR4, PKCα and occludin expression

under different treatments

The mRNA and protein expression levels of TLR4, PKCα

and occludin in BMECs were examined in the four different treatment

groups. RT-qPCR analysis indicated no significant differences in

TLR4 expression between the three different treatment groups

compared with the untreated Control (Fig. 2A). However, PKCα mRNA expression

levels were significantly reduced in the PKCα-siRNA treatment group

and the TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA treatment group compared with expression

levels in the Control and TAK-242-only groups (P<0.01; Fig. 2B). No significant differences were

identified for PKCα expression between the Control and TAK-242

groups; no significant differences were identified for PKCα

expression between the PKCα-siRNA and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA groups.

These results suggested that the alteration in PKCα expression was

due to PKCα-siRNA treatment, not by TAK-242. The effects of the

treatments on occludin mRNA expression levels were also examined.

The results demonstrated that occludin mRNA expression was

significantly increased in each of the treatment groups compared

with the Control group (Fig. 2C).

Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in occludin

expression between the PKCα-siRNA and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA groups.

These data suggested that alteration in occludin expression may be

triggered by PKCα-siRNA treatment. Meanwhile, TAK-242 treatment

alone could also induce the increased occludin expression (Fig. 2C). No difference of TLR4 protein

expression was observed between the 4 groups. PKCα protein

expressions in PKCα-siRNA group (P<0.05) and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA

group (P<0.05) were significantly lower than that in Control

group. Meanwhile, Occludin protein expressions in TAK-242 group

(P<0.05), PKCα-siRNA group (P<0.05) and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA

group (P<0.01) were significant higher compared with the Control

group. Western blot analysis revealed similar results as those of

the RT-qPCR analysis (Fig. 2D and

E).

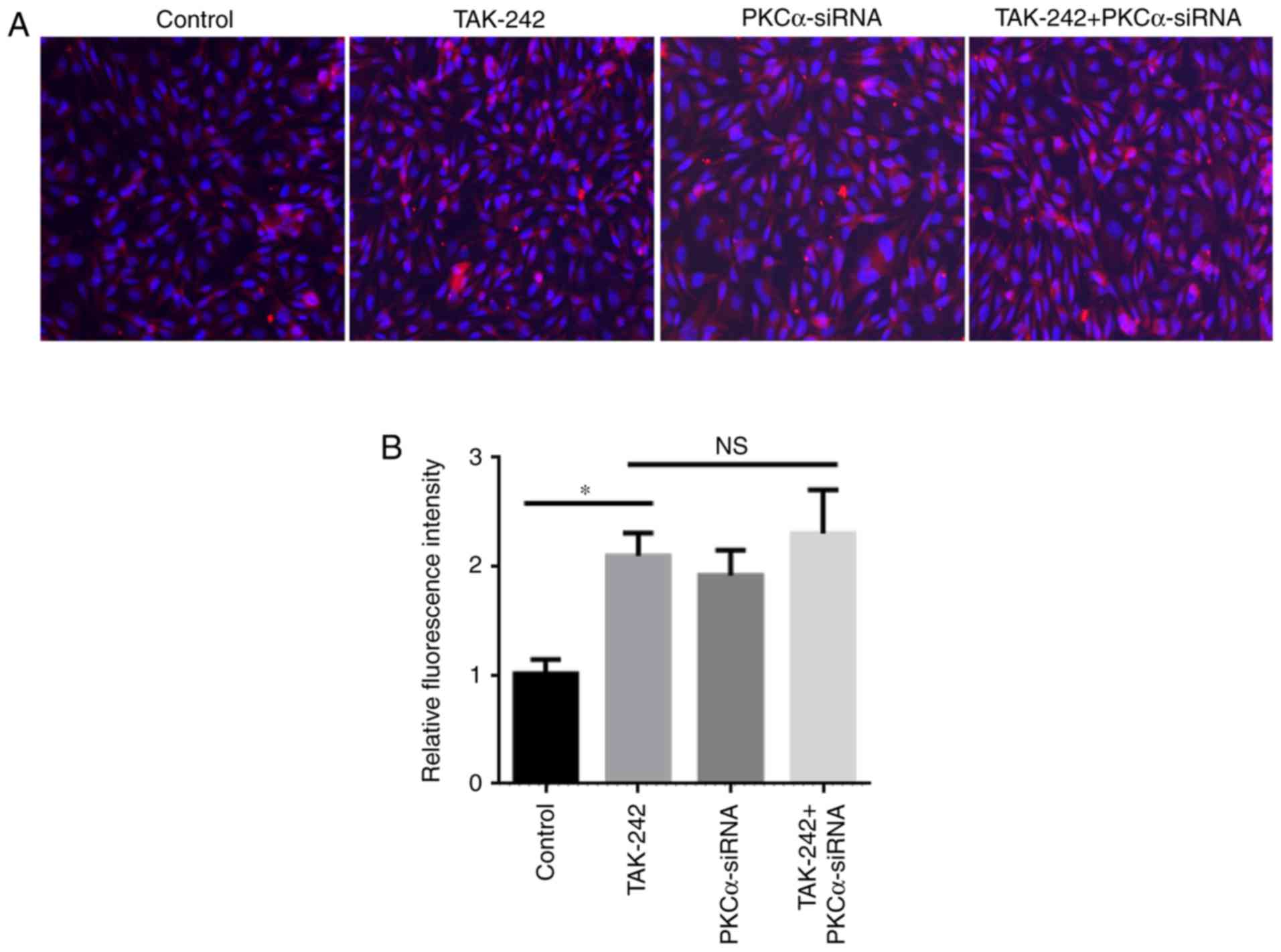

Increased expression of occludin

protein under different treatments

The expression and localization of the occludin

protein were examined in the four BMEC treatment groups (Fig. 3). Immunostaining analysis of

different BMEC treatments had demonstrated that occludin expression

in TAK-242 group, PKCα-siRNA group, and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA group

were significantly increased compared with the Control group

(Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, no

significantly difference in occludin protein expression was

observed between the TAK-242 and PKCα-siRNA groups. These results

indicated that TAK-242 and PKCα-siRNA treatments may serve similar

roles in the expression and location of occludin.

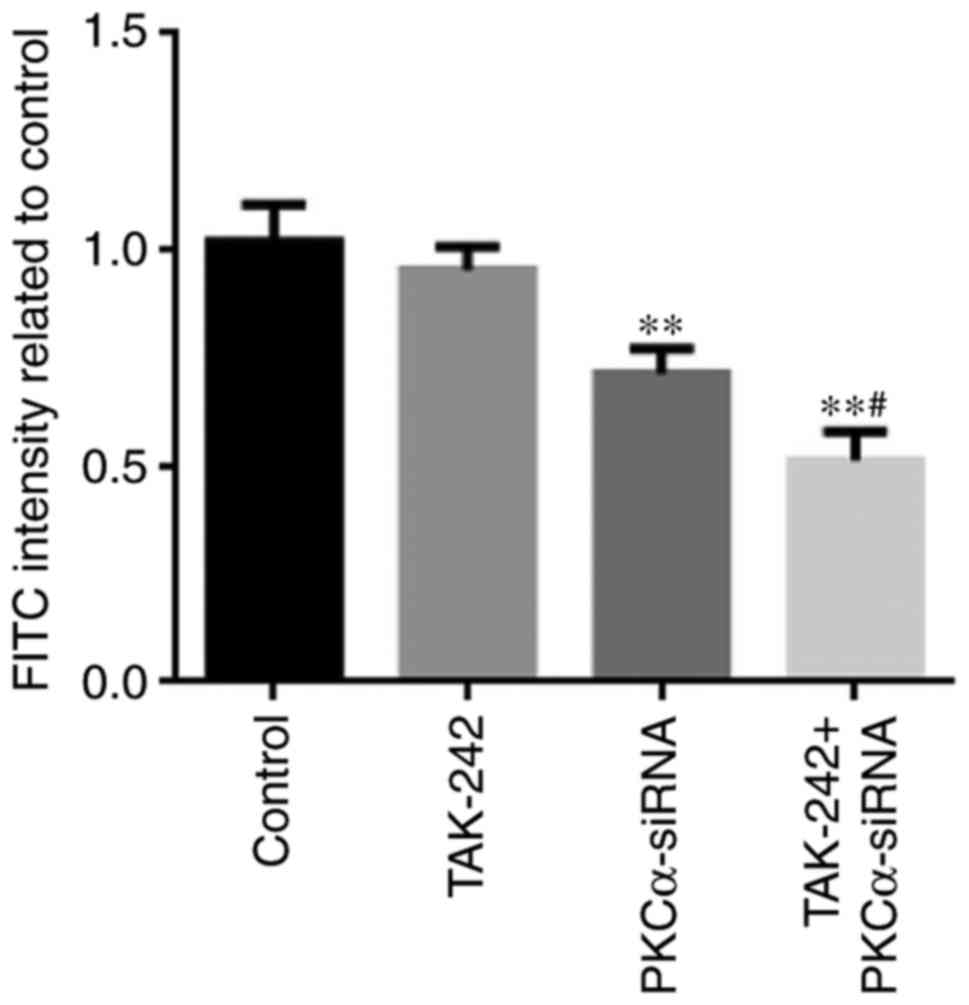

Permeability

Endothelial permeability was determined by measuring

the passage of FITC-labeled dextran through the BMEC monolayer

(Fig. 4). The permeability of

PKCα-siRNA and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA treated cells was significantly

decreased compared with untreated Control cells (P<0.01). These

results suggested that endothelial permeability decrease was mainly

caused by PKCα-siRNA treatment, which could be promoted by adding

TAK-242 to PKCα-siRNA treatment. However, it was notable that

TAK-242 treatment alone could not induce any changes in endothelial

permeability.

Discussion

As a gatekeeper, the BBB allows molecules that are

required by the brain, such as oxygen and hormones, to pass into

the brain extracellular fluid, and prevents other substances from

entering, including metabolic and environmental toxins and

bacteria. The BBB also actively transports essential molecules

including TNF-α and interleukin in certain metabolic pathways.

Clinical and experimental observations have indicated that hypoxia

alters the integrity of the BBB; however, the intracellular

signaling mechanisms that regulate TJ proteins at the BBB remain

poorly understood (31). Although

several studies have demonstrated the importance of PKC in

regulating BBB function (32–34),

the roles of PKCα, TLR4, and occludin in BBB regulation and their

mechanisms are unclear. To determine the link between TLR4,

occludin and PKCα activity, BMECs were used as a BBB model in the

present study.

Occludin is considered to be the main sealing

protein owing to its highly complicated structure (35), which comprises two equal

extracellular loops, four transmembrane domains and three

cytoplasmic domains (36,37). The N-terminal site is crucial for

its function and a mutant N-terminal may lead to the failure of

complete TJ complex assembly (38). Vascular endothelial cells serve an

important role in adjusting homeostasis and response to

inflammation (39,40). Endothelial cells are regulated by

physiological agonists and stress stimuli; endothelial cell

activation is closely related with intracellular signaling

pathways, including the synthesis and release of inflammation

mediators, adhesion molecule induction and the actin cytoskeleton,

which govern motility and permeability (41,42).

Endothelial dysfunction may lead to damage to the endothelial

integrity and cardiovascular pathology, such as atherosclerosis,

hypertension and coagulation abnormalities (43). The crucial role of occludin to the

integrity of tight junctions has been reported in both in

vitro and in vivo studies (44,45).

Knockout-occludin−/− treated mice showed morphologically

intact tight junctions (46), but

all showed poor TJ integrity and mucosal barrier dysfunction in

further in-depth analyses. These data indicated an important role

for occludin in TJ stability and barrier function. The present

study evaluated the effects of four different treatments on the

expression and localization of the occludin protein (Fig. 3). The results demonstrated that the

expressions of occludin in the three treatment groups were

significantly increased compared with the Control group. TAK-242

has been reported that it was an inhibitor for TLR4 (47). Therefore, it was hypothesized that

TAK-242 treatment and PKCα-siRNA treatment should function through

the same TLR4/PKCα/occludin signaling pathway, resulting in the

similar occludin expression. The permeability observed in the

PKCα-siRNA and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA groups was significantly

decreased compared with the Control group. The present study

hypothesized that PKCα-siRNA treatment also was the major factor

decreasing permeability, which was reinforced by TLR4 inhibitor

treatment. However, TAK-242 treatment alone was not able to

significantly decrease the BMEC permeability. RT-qPCR analysis

indicated no significant difference of TLR4 expression in three

different treatments compared with the Control group, which may be

due to TAK-242 inhibiting TLR4 activity through protein level but

not the mRNA expression level. However, this hypothesis requires

further experimentation to verify. No significant difference was

identified for PKCα mRNA expression and protein expression between

cells treated with PKCα-siRNA and cells treated with

TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA. This result indicated that the changes in TLR4

mRNA and protein should not be associated with PKCα expression. The

expressions of occludin in TAK-242 group (P<0.05), PKCα-siRNA

group (P<0.05) and TAK-242+PKCα-siRNA group (P<0.01) were

significantly increased compared with the Control group. This

implied that occludin expression could be changed by TAK-242

treatment, PKCα-siRNA treatment, or the two together. Western blot

analysis was also performed to examine the effects of four

different treatments on occludin protein expression, and this

revealed similar results to RT-qPCR analysis.

The present study has a number of limitations,

including the behaviors comparisons of different cell lines treated

with PKCα-siRNA and a TAK-242 were not performed. The use of

different cell lines may provide more comprehensive information

about the TLR4/PKCα/occludin signaling pathway as it pertains to

BBB damage. Another limitation is that animal experiments in

vivo were not performed. The cell experiments may have been

affected by multiple factors, such as cell state, environment and

human factors. Animal experiments may effectively reflect the real

regulatory process in vivo. Therefore, animal experiments

are required.

In conclusion, PKCα may serve a negative feedback

role in occludin expression, although no obvious connection was

identified between PKCα and TLR4. However, PKCα-siRNA treatment was

able to affect permeability, which was reinforced by the TLR4

inhibitor. However, TAK-242 treatment alone may not be effective in

changing BMEC permeability. Understanding the specific roles of

TLR4/PKCα and occludin in damage to the BBB may lead to an improved

understanding of the molecular mechanisms in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bingquan Lai from Forevergen

Biosciences Co., Ltd. for his valuable suggestion for the present

study.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Funds of China (grant nos. 81460290, 81360287 and

81560039), the Natural Science Fund of Jiangxi Province (grant no.

20142BAB205041), the Natural Science Fund of Guangdong Province

(grant no. 2015A030313168), the Educational Department Fund of

Jiangxi Province (grant no. GJJ14695) and the Health and Planning

Family Commission Fund of Jiangxi Province (grant no.

20155427).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

ZL and CX conceived and designed the study, and

critically revised the manuscript. ZT and DG performed the

experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. LX, BW,

XX, JF and LK participated in study design, study implementation

and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experiments were performed according to the

relevant guidelines published by the Ministry of Agriculture of

China. All protocols were approved by the Institute of Animal

Sciences at the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical

University (Ganzhou, China), where the experiments were

conducted.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Griepp RB, Stinson EB, Hollingsworth JF

and Buehler D: Prosthetic replacement of the aortic arch. J Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg. 70:1051–1063. 1975.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wypij D, Newburger JW, Rappaport LA,

duPlessis AJ, Jonas RA, Wernovsky G, Lin M and Bellinger DC: The

effect of duration of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in infant

heart surgery on late neurodevelopment: The boston circulatory

arrest trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 126:1397–1403. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ronaldson PT and Davis TP: Blood-brain

barrier integrity and glial support: Mechanisms that can be

targeted for novel therapeutic approaches in stroke. Curr Pharm

Des. 18:3624–3644. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu WY, Wang ZB, Zhang LC, Wei X and Li L:

Tight junction in blood-brain barrier: An overview of structure,

regulation, and regulator substances. CNS Neurosci Ther.

18:609–615. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Shin K, Fogg VC and Margolis B: Tight

junctions and cell polarity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 22:207–235.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fanning AS and Anderson JM: Zonula

occludens-1 and −2 are cytosolic scaffolds that regulate the

assembly of cellular junctions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1165:113–120.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Runkle EA and Mu D: Tight junction

proteins: From barrier to tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 337:41–48.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Minagar A, Maghzi AH, McGee JC and

Alexander JS: Emerging roles of endothelial cells in multiple

sclerosis pathophysiology and therapy. Neurol Res. 34:738–745.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cummins PM: Occludin: One protein, many

forms. Mol Cell Biol. 32:242–250. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gerber J, Heinrich J and Brehm R:

Blood-testis barrier and Sertoli cell function: Lessons from

SCCx43KO mice. Reproduction. 151:R15–R27. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Capaldo CT and Nusrat A: Cytokine

regulation of tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1788:864–871.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Krause G, Winkler L, Mueller SL, Haseloff

RF, Piontek J and Blasig IE: Structure and function of claudins.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1778:631–645. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vandenbroucke St Amant E, Tauseef M, Vogel

SM, Gao XP, Mehta D, Komarova YA and Malik AB: PKCα activation of

p120-catenin serine 879 phospho-switch disassembles VE-cadherin

junctions and disrupts vascular integrity. Circ Res. 111:739–749.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Singh I, Knezevic N, Ahmmed GU, Kini V,

Malik AB and Mehta D: Galphaq-TRPC6-mediated Ca2+ entry induces

RhoA activation and resultant endothelial cell shape change in

response to thrombin. J Biol Chem. 282:7833–7843. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hutchinson TE, Zhang J, Xia SL,

Kuchibhotla S, Block ER and Patel JM: Enhanced phosphorylation of

caveolar PKC-α limits peptide internalization in lung endothelial

cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 360:309–320. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Alonso A and Gonzalez C: Neuroprotective

role of estrogens: Relationship with insulin/IGF-1 signaling. Front

Biosci (Elite Ed). 4:607–619. 2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Melkamu T, Squillace D, Kita H and O'Grady

SM: Regulation of TLR2 expression and function in human airway

epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 229:101–113. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Su W, Mruk DD and Cheng CY: Regulation of

actin dynamics and protein trafficking during

spermatogenesis-insights into a complex process. Crit Rev Biochem

Mol Biol. 48:153–172. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cuschieri J, Billigren J and Maier RV:

Endotoxin tolerance attenuates LPS-induced TLR4 mobilization to

lipid rafts: A condition reversed by PKC activation. J Leukoc Biol.

80:1289–1297. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li X, Wang C, Nie J, Lv D, Wang T and Xu

Y: Toll-like receptor 4 increases intestinal permeability through

up-regulation of membrane PKC activity in alcoholic

steatohepatitis. Alcohol. 47:459–465. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Peng Y, Sigua CA, Rideout D and Murr MM:

Deletion of toll-like receptor-4 downregulates protein kinase

C-zeta and attenuates liver injury in experimental pancreatitis.

Surgery. 143:679–685. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang Y, Chen H and Yang L: Toll-like

receptor 4 participates in gastric mucosal protection through Cox-2

and PGE2. Dig Liver Dis. 42:472–476. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Molnár K, Vannay A, Szebeni B, Bánki NF,

Sziksz E, Cseh A, Győrffy H, Lakatos PL, Papp M, Arató A and Veres

G: Intestinal alkaline phosphatase in the colonic mucosa of

children with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol.

18:3254–3259. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Eun CS, Han DS, Lee SH, Paik CH, Chung YW,

Lee J and Hahm JS: Attenuation of colonic inflammation by PPARgamma

in intestinal epithelial cells: Effect on Toll-like receptor

pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 51:693–697. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Rigor RR, Beard RS Jr, Litovka OP and Yuan

SY: Interleukin-1β-induced barrier dysfunction is signaled through

PKC-θ in human brain microvascular endothelium. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 302:C1513–C1522. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Naik P and Cucullo L: In vitro blood-brain

barrier models: Current and perspective technologies. J Pharm Sci.

101:1337–1354. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Irie N, Sakai N, Ueyama T, Kajimoto T,

Shirai Y and Saito N: Subtype- and species-specific knockdown of

PKC using short interfering RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

298:738–743. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen C, Mei H, Shi W, Deng J, Zhang B, Guo

T, Wang H and Hu Y: EGFP-EGF1-conjugated PLGA nanoparticles for

targeted delivery of siRNA into injured brain microvascular

endothelial cells for efficient RNA interference. PLoS One.

8:e608602013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ii M, Matsunaga N, Hazeki K, Nakamura K,

Takashima K, Seya T, Hazeki O, Kitazaki T and Iizawa Y: A novel

cyclohexene derivative, ethyl

(6R)-6-[N-(2-Chloro-4-fluorophenyl)sulfamoyl]cyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylate

(TAK-242), selectively inhibits toll-like receptor 4-mediated

cytokine production through suppression of intracellular signaling.

Mol Pharmacol. 69:1288–1295. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Daneman R: The blood-brain barrier in

health and disease. Ann Neurol. 72:648–672. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

You K, Xu X, Fu J, Xu S, Yue X, Yu Z and

Xue X: Hyperoxia disrupts pulmonary epithelial barrier in newborn

rats via the deterioration of occludin and ZO-1. Respir Res.

13:362012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fleegal MA, Hom S, Borg LK and Davis TP:

Activation of PKC modulates blood-brain barrier endothelial cell

permeability changes induced by hypoxia and posthypoxic

reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 289:H2012–H2019.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Willis CL, Meske DS and Davis TP: Protein

kinase C activation modulates reversible increase in cortical

blood-brain barrier permeability and tight junction protein

expression during hypoxia and posthypoxic reoxygenation. J Cereb

Blood Flow Metab. 30:1847–1859. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lameris AL, Huybers S, Kaukinen K, Mäkelä

TH, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG and Nevalainen PI: Expression

profiling of claudins in the human gastrointestinal tract in health

and during inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol.

48:58–69. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

dela Paz NG, Walshe TE, Leach LL,

Saint-Geniez M and D'Amore PA: Role of shear-stress-induced VEGF

expression in endothelial cell survival. J Cell Sci. 125:831–843.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Buschmann MM, Shen L, Rajapakse H, Raleigh

DR, Wang Y, Wang Y, Lingaraju A, Zha J, Abbott E, McAuley EM, et

al: Occludin OCEL-domain interactions are required for maintenance

and regulation of the tight junction barrier to macromolecular

flux. Mol Biol Cell. 24:3056–3068. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Schmidt E, Kelly SM and van der Walle CF:

Tight junction modulation and biochemical characterisation of the

zonula occludens toxin C-and N-termini. FEBS Lett. 581:2974–2980.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lee WL and Liles WC: Endothelial

activation, dysfunction and permeability during severe infections.

Curr Opin Hematol. 18:191–196. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Speyer CL and Ward PA: Role of endothelial

chemokines and their receptors during inflammation. J Invest Surg.

24:18–27. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lamalice L, Le Boeuf F and Huot J:

Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ Res.

100:782–794. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Tremblay PL, Auger FA and Huot J:

Regulation of transendothelial migration of colon cancer cells by

E-selectin-mediated activation of p38 and ERK MAP kinases.

Oncogene. 25:6563–6573. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Schulz E, Gori T and Munzel T: Oxidative

stress and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertens Res.

34:665–673. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ulluwishewa D, Anderson RC, McNabb WC,

Moughan PJ, Wells JM and Roy NC: Regulation of tight junction

permeability by intestinal bacteria and dietary components. J Nutr.

141:769–776. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

González-Mariscal L, Tapia R and Chamorro

D: Crosstalk of tight junction components with signaling pathways.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1778:729–756. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wardill HR, Gibson RJ, Logan RM and Bowen

JM: TLR4/PKC-mediated tight junction modulation: A clinical marker

of chemotherapy-induced gut toxicity? Int J Cancer. 135:2483–2792.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Matsunaga N, Tsuchimori N, Matsumoto T and

Ii M: TAK-242 (resatorvid), a small-molecule inhibitor of Toll-like

receptor (TLR) 4 signaling, binds selectively to TLR4 and

interferes with interactions between TLR4 and its adaptor

molecules. Mol Pharmacol. 79:34–41. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|