Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune

disorder. It affects the joints, to eventually result in joint

deformities (1), and influences

other parts of the body; symptoms include a low red blood cell

count, and inflammation around the lungs and heart (2). Age is a risk factor for RA, and RA is

considered a global health risk as the aging population increases

in a number of countries (3). At

present, RA treatments predominantly focus on reducing pain and

inflammation to improve patient quality of life (4).

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes are highly specialized

cells in the joint synovial membrane, which are considered to be

involved in the pathogenesis of RA (5). The synovial membrane is located

between the joint capsule and the joint cavity, which reduces

friction between the joint cartilage and supplies nutrients to the

surrounding cartilage (6).

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes are one of the two principal cell

types in the intima of the synovial membrane, and are essential for

internal joint homeostasis (7).

During RA progression, the physiology of fibroblast-like

synoviocytes is markedly altered; contact inhibition properties are

lost and excessive proliferation occurs. Furthermore, these cells

begin to secrete numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines, including

interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-18, which

creates an inflammatory environment in the synovium and contributes

to the destruction of the joint (5,8).

The nuclear factor (NF)-κB/NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3) signaling pathway is the central hub of the

inflammatory response, which mediates the transcription of a large

number of pro-inflammatory genes, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and

IL-18 (9,10). Overactivation of the NF-κB pathway

results in multiple inflammatory diseases, including RA (11). Inhibition of NF-κB activity

markedly ameliorates the symptoms of RA (12).

Galangin is a natural flavonoid extracted from the

roots of Alpinia officinarum. In South Africa, this

traditional herb is used to treat infection (13). Galangin has exhibited multiple

beneficial properties, including anti-oxidative,

anti-proliferative, immunoprotective and cardioprotective effects

(14). Among these, the

anti-inflammatory properties of galangin have gained the attention

of researchers in the RA field (15–17).

As the potential of galangin in treating RA has

previously been demonstrated (18,19),

the present study attempted to investigate the mechanisms

underlying the protective effects of galangin in RA fibroblast-like

synoviocytes.

Materials and methods

Cell line and reagents

Primary human RA fibroblast-like synovium cells

(RAFSCs; cat. no. JNO17-929) were purchased from Guangzhou Jennio

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Galangin was purchased

from Sichuan Weikeqi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu,

China). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was obtained from Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Primary

antibodies against inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; cat. no.

ab3523) and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 (cat. no. ab15191) were

purchased, including anti-NLRP3 (cat. no. ab4207; all Abcam,

Cambridge, UK), anti-apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing A (ASC; cat. no. sc-22514-R), anti-IL-1β (cat. no.

sc-1250), anti-pro-caspase-1 (cat. no. sc-514), anti-caspase-1

(cat. no. sc-56036), anti-phosphorylated (p)-NF-κB inhibitor α

(IκBα; cat. no. sc-8404), anti-IκBα (cat. no. sc-847), anti-p-NF-κb

(cat. no. sc-101749) and anti-NF-κB (cat. no. sc-109; all Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Horseradish peroxidase

(HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and fluorescent-labeled

(SABC-DyLight 488) secondary antibodies (cat. no. SA1033) were

purchased from Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd. (Wuhan,

China).

Cell culture

RAFSCs were cultured in complete medium [Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM); Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA] containing 10% fetal calf serum

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were used. Primary keratinocytes were incubated in

DMEM for 24 h at 37°C in the dark with 1 mg/ml freshly made

alanine, and Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) at a ratio

of 50:1 (P. acnes: keratinocytes) for starvation. Following

starvation, cells were cultured with LPS and different doses of

galangin. Nothing was added to the control group. LPS (1 µg/ml) in

combination with galangin (0, 1, 5 and 10 ng/ml) was added to each

group. Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and subsequently

collected for further experimentation. All cells were adherent.

ELISA

RAFSCs were homogenized in PBS and centrifuged at

1,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatant (1 ml) was subjected to

ELISA detection of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-18, prostaglandin

(PG)E2, and nitric oxide (NO) levels using the

Quantikine ELISA kit (cat. no. DHD00B; R&D Systems, Inc.,

Minneapolis, MN, USA) and the PGE2 ELISA Correlate EIA™ kit (cat.

no. ab133021; Abcam), according to the manufacturers' protocols.

The absorbance of the samples at 450 nm was detected using a

microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Measurement of superoxide dismutase

(SOD) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) content

In order to investigate the antioxidant effect of

galangin, SOD activity and MDA content in RAFSCs was measured. At

the end of incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the cell solution was

centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Culture supernatant and

lysate was collected. SOD activity and MDA content was measured

using a Cell MDA assay kit purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute (cat. no. A003-1; Nanjing, China),

according to the manufacturer's protocol. The absorbance of SOD and

MDA was detected using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 550 and 450 nm, respectively.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from RAFSCs using 1% SDS

lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China),

and protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid

protein assay. Proteins (40 µg/lane) were loaded and separated by

12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride

membranes. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against

NLRP3 (1:800), ASC (1:1,000), IL-1β (1:900), pro-caspase-1

(1:1,000), caspase-1 (1:1,000), p-IκBα (1:1,200), IκBα (1:900),

anti-p-NF-κB (1:1,000), anti-NF-κB (1:1,000), anti-β-actin

(1:2,000; cat. no. ab8227; Abcam), anti-iNOS (1:800) and anti-COX-2

(1:900) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and fluorescent-labeled

secondary antibodies (1:10,000; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology,

Ltd.) at 37°C for 2 h. Enhanced chemiluminescence (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) solution was added and the blots were

exposed on X-ray films in a dark room. Images were subsequently

captured, and Bandscan software version 5.0 (Glyko, Inc.; BioMarin

Pharmaceutical, Inc., Novato, CA, USA) was used for analysis of the

gel images.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation (n=6), and statistical analysis was performed with SPSS

11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance

followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was used to determine significant

differences between multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Galangin inhibits LPS-induced IL-1β,

TNF-α, IL-18, PGE2 and NO expression levels in

RAFSCs

The effects of galangin on the expression of IL-1β,

TNF-α and IL-18 in RAFSCs were determined by ELISA. As presented in

Table I, the expression of these

cytokines was strongly induced by LPS (P<0.05), with an increase

of 4–7 fold. However, when cells were pre-treated with galangin and

LPS, IL-18, IL-1β and TNF-α expression was significantly inhibited

(P<0.05; Table I). When cells

were treated with 10 ng/ml galangin, IL-1β and TNF-α expression was

comparable to the control group; IL-18 expression was additionally

markedly inhibited, compared with the LPS only group. These

findings suggested that galangin inhibited LPS-induced IL-1β, TNF-α

and IL-18 expression in RAFSCs in a concentration-dependent manner,

highlighting its potential anti-inflammatory effects.

| Table I.Expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α,

IL-18, PGE2 and NO in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synovium

cells treated with LPS and/or galangin. |

Table I.

Expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α,

IL-18, PGE2 and NO in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synovium

cells treated with LPS and/or galangin.

|

| Marker |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Group | IL-1β | TNF-α | IL-18 | PGE2, ng/ml | NO, µmol/ml |

|---|

| Control |

65.21±3.12a–d |

29.47±1.28a–d |

35.47±9.64a–d |

0.11±0.08a–d |

35.74±3.56a,b |

| LPS only |

279.36±20.78b–d |

167.34±32.15b–d |

234.97±21.45b–d |

2.51±0.15b–d |

298.09±37.45b–d |

| LPS + 1 ng/ml

galangin |

135.27±12.34a,c,d |

82.39±19.85a,c,d |

135.65±11.67a,c,d |

1.45±0.26a,c,d |

68.17±28.57a,c,d |

| LPS + 5 ng/ml

galangin |

93.74±9.85a,b,d |

61.46±14.61a,b,d |

85.76±9.73a,b,d |

1.02±0.32a,b,d |

37.12±9.78a,b |

| LPS + 10 ng/ml

galangin |

76.51±15.67a–c |

39.27±5.8a–c |

62.21±4.38a–c |

0.39±0.18a–c |

34.37±7.62a,b |

Levels of PGE2 and NO in the RAFSC

culture supernatant were additionally detected by ELISA, in order

to investigate whether galangin regulated LPS-induced NO and

PGE2 production. As presented in Table I, PGE2 and NO levels

were significantly increased by LPS, compared with the control

group (P<0.05). Furthermore, PGE2 and NO levels were

suppressed with galangin treatment (P<0.05 vs. LPS only group).

These results demonstrated that galangin inhibited the LPS-induced

expression of PGE2 and NO in RAFSCs.

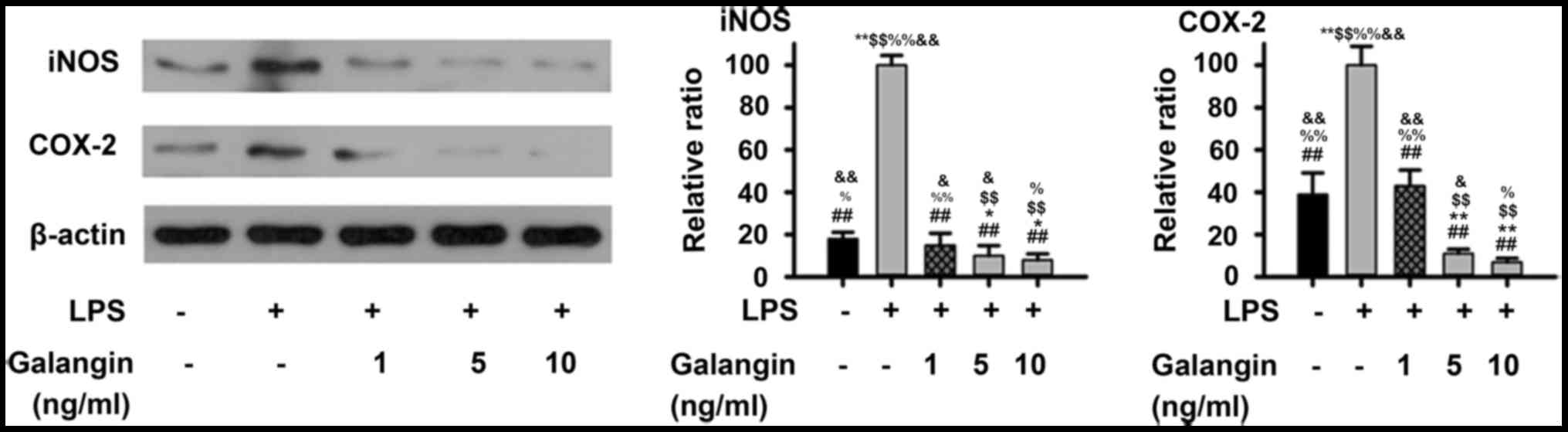

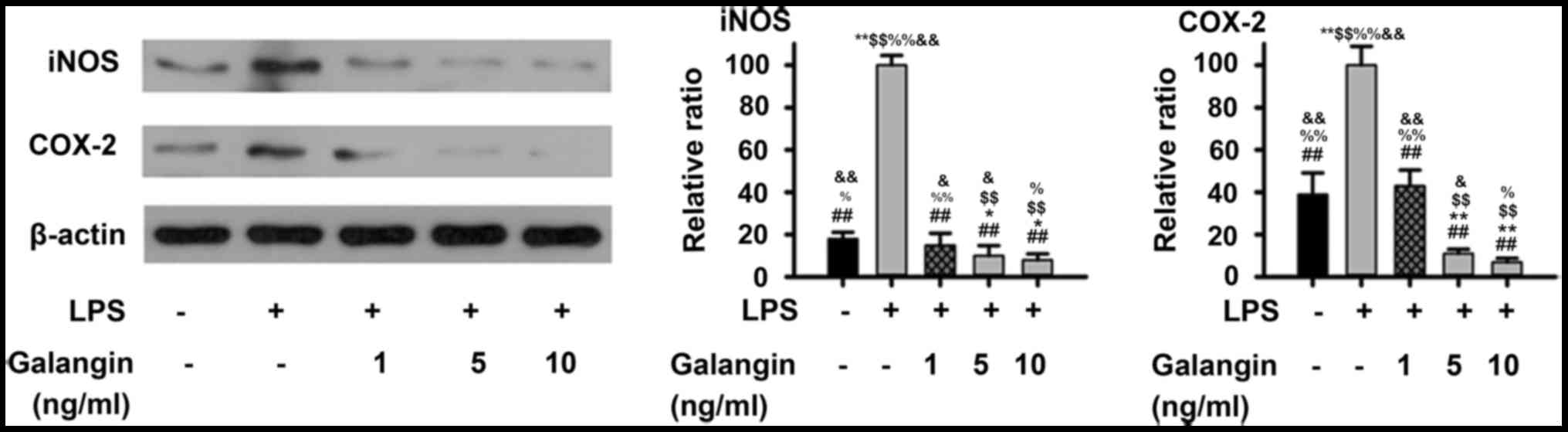

Galangin inhibits the LPS-induced

expression of iNOS and COX-2 in RAFSCs

Considering that galangin inhibited NO and PGE2

production, western blot analysis was performed in order to examine

whether these inhibitory effects were associated with iNOS and

COX-2 regulation in RAFSCs. As presented in Fig. 1, LPS significantly increased the

expression of iNOS and COX-2 (P<0.01). Pre-treatment with 1

ng/ml galangin decreased iNOS and COX-2 expression (P<0.05),

which was not significantly different when compared with the

control (P>0.05). At a dose of 5 or 10 ng/ml, the iNOS and COX-2

expression levels decreased below those of the control group

(P<0.05). Therefore, these results demonstrated that galangin

inhibited LPS-induced expressions of iNOS and COX-2 in RAFSCs.

| Figure 1.Expression levels of iNOS and COX-2 in

RAFSCs treated with LPS and/or galangin. In the LPS group, cells

were treated with 1 µg/ml LPS only. In the galangin groups, cells

were treated with 1 µg/ml LPS and galangin at 1, 5 or 10 ng/ml. The

LPS group had significantly elevated levels of iNOS and COX-2

compared with the control group. Cells treated with galangin had

significantly lower levels, compared with the LPS group.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control group; ##P<0.01

vs. LPS group; $$P<0.01 vs. LPS + galangin (1 ng/ml);

%P<0.05, %%P<0.01 vs. LPS + galangin (5

ng/ml); &P<0.05, &&P<0.01

vs. LPS + galangin (10 ng/ml). iNOS, inducible nitric oxide

synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; RAFSCs, rheumatoid arthritis

fibroblast-like synovium cells; LPS, lipopolysaccharide. |

Galangin decreases SOD activity and

increases MDA content

It was demonstrated that LPS significantly decreased

SOD activity (P<0.05), and pre-treatment with galangin increased

SOD activity (P<0.05) (Fig. 2).

MDA content had an opposite tendency, with galangin decreasing the

levels of MDA. These findings provided evidence that galangin

exhibited antioxidative effects in RAFSCs.

Galangin suppresses the NF-κB/NLRP3

signaling pathway

The NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway, which upregulates multiple

pro-inflammatory cytokines, has been considered to be a key

signaling pathway in the progression of RA (12). In order to understand the

underlying mechanisms of the protective effects of galangin in

RAFSCs, the expression of multiple factors in the NF-κB/NLRP3

signaling pathway were measured by western blot analysis. The

expression of NLRP3, ASC, IL-1β, pro-caspase-1, caspase-1, p-IκBα

and p-NF-κB in RAFSCs was upregulated by LPS stimulation

(P<0.05) (Fig. 3).

Pre-treatment with galangin (1 ng/ml) decreased ASC,

pro-caspase-1/caspase-1, p-IκBα and p-NF-κB (P<0.05) expression;

however, it did not significantly decrease NLRP3 or IL-1β

expression. Pre-treatment with 5 or 10 ng/ml galangin significantly

attenuated the LPS-induced overexpression of all these factors

(P<0.05). These results indicated that galangin may have

protected RAFSCs by suppressing the NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling

pathway.

| Figure 3.Expression of proteins associated with

the NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway in RAFSCs treated with LPS and/or

galangin. (A) Western blot analysis. The LPS group had

significantly elevated levels of (B) NLRP3, (C) ASC, (D)

pro-caspase-1/caspase-1, (E) IL-1β, (F) p-IκBα and (G) p-NF-κB.

When RAFSCs were pre-treated with 1 ng/ml galangin, expression

levels of ASC, p-IκBα, p-NF-κB were significantly lower compared

with the LPS group, whereas when the cells were pre-treated with 5

or 10 ng/ml galangin, the expression of all proteins was

significantly lower, compared with the LPS group. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 vs. control group; ##P<0.01 vs. LPS

group; $$P<0.01 vs. LPS + galangin (1 ng/ml);

%P<0.05, %%P<0.01 vs. LPS + galangin (5

ng/ml); &P<0.05, &&P<0.01

vs. LPS + galangin (10 ng/ml). NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NLRP3, NLR

family pyrin domain containing 3; RAFSCs, rheumatoid arthritis

fibroblast-like synovium cells; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ASC,

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing A; IL-1β,

interleukin-1β; p-, phosphorylated; IκBα, NF-κB inhibitor α. |

Discussion

RA is a systemic immune and inflammatory disease.

For the majority of patients, RA is a progressive, life-long

disease that shortens life expectancy by 3–20 years (20). Unfortunately, despite extensive

research, RA pathogenesis remains unclear, and there is currently

no cure for this disease (21).

Bacterial LPS is capable of eliciting a strong

immune response in vitro and in vivo, and is

frequently used to induce symptoms of RA (22). IL-18, IL-1β and TNF-α are

pro-inflammatory cytokines that have pivotal roles in RA, and are

frequently used as inflammatory markers (23,24).

Furthermore, a number of factors downstream of proinflammatory

cytokines are responsible for creating an inflammatory environment

around the joint. For example, NO is a free radical that is

generated enzymatically by the cytokine-induced iNOS pathway and

contributes to the pathogenesis of arthritis (25). In addition, one tissue specific

isoform of COX-2 produces PGE2, which aggravates

synovial inflammation by increasing local blood flow and

vasopermeability (26).

Furthermore, TNF-α and other pro-inflammatory cytokines enhance the

production of COX-2 and PGE2 (27). All these factors were considered as

incentives in RA.

Therefore, the present study investigated the

inhibitory effect of galangin on the LPS-induced increase in IL-1β,

TNF-αIL-18, PGE2, NO, iNOS and COX-2 expression levels

in RAFSCs. The results indicated that galangin significantly

inhibited the release of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-18, PGE2, NO

into the medium, in addition to iNOS and COX-2. The observed

reduction in NO production and PGE2 release when cells

were pretreated with galangin may have resulted from the

transcriptional suppression of iNOS and COX-2. However, a

limitation of the present study was that the effect of treatment

with galangin on cell survival and apoptosis was not evaluated.

Free radicals cause damage to cellular components

and contribute to the development of numerous inflammatory diseases

(28). SOD is an enzyme that

reduces the damage of superoxides and MDA is a marker for oxidative

stress; the expression of these molecules is negatively and

positively associated with RA symptoms, respectively (29). In the present study, it was

revealed that galangin decreased LPS-induced cytokine expression in

the RAFSC culture supernatant, and therefore may have protected

cells from cytokine-induced damage. The antioxidative effects of

galangin were also investigated. Galangin exhibited significant

antioxidant effects, as evidenced by the increased SOD activity and

lower MDA content detected. Cells treated with 1 or 5 ng/ml

galangin had significant differences in expression compared with

the LPS only treatment group, in SOD activity and MDA content. The

increase in SOD activity suggested that galangin enhanced the

antioxidant capability of the cells, while the decrease in MDA

content indicated that galangin may have reduced lipid membrane

oxidation by scavenging free radicals. Although SOD activity and

MDA content may be sufficient to draw the conclusion that galangin

had antioxidative effect on RAFSCs, in vivo experiments to

visualize cellular ROS with molecular dye or other methods may

further elucidate the function of galangin in reducing the

inflammatory response. Therefore, further studies in vivo

are required in the future.

A previous study suggested that galangin prevents

osteoclastic bone destruction and osteoclastogenesis in osteoclast

precursors, and additionally in collagen-induced arthritis mice,

without toxicity via attenuation of TNF superfamily member

11-induced activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase

(MAPK)8, MAPK14 and NF-κB signaling pathways (18). In the present study, it was

determined that the protective effects of galangin in RAFSCs were

likely due to NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway downregulation.

As a result, it was concluded that galangin

suppressed pro-inflammatory signaling in fibroblast-like

synoviocytes in vitro, and that inhibition of the

NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway was a key mechanism in this protective effect.

Therefore, galangin may provide a novel direction for the

development of RA therapies in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the current

study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

QF, YG, HZ, ZW and JW were responsible for the

conception and design of the study. QF, YG and HZ performed the

experiments, and analyzed and interpreted the data. QF drafted the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chang X, He H, Zhu L, Gao J, Wei T, Ma Z

and Yan T: Protective effect of apigenin on Freund's complete

adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats via inhibiting P2×7/NF-κB

pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 236:41–46. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Majithia V and Geraci SA: Rheumatoid

arthritis: Diagnosis and management. Am J Med. 120:936–939. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S,

Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et

al: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20

age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global

burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 380:2095–2128. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J,

Finney C, Curtis JR, Paulus HE, Mudano A, Pisu M, Elkins-Melton M,

et al: American college of rheumatology 2008 recommendations for

the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic

drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 59:762–784. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bartok B and Firestein GS: Fibroblast-like

synoviocytes: Key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol

Rev. 233:233–255. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

de Sousa EB, Casado PL, Moura Neto V,

Duarte ME and Aguiar DP: Synovial fluid and synovial membrane

mesenchymal stem cells: Latest discoveries and therapeutic

perspectives. Stem Cell Res Ther. 5:1122014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chang SK, Gu Z and Brenner MB:

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes in inflammatory arthritis pathology:

The emerging role of cadherin-11. Immunol Rev. 233:256–266. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Firestein GS: Evolving concepts of

rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 423:356–361. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Simmonds RE and Foxwell BM: Signalling,

inflammation and arthritis: NF-kappaB and its relevance to

arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 47:584–590.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Baldwin AS Jr: The NF-kappa B and I kappa

B proteins: New discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol.

14:649–683. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tak PP and Firestein GS: NF-kappaB: A key

role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 107:7–11. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yamamoto Y and Gaynor RB: Therapeutic

potential of inhibition of the NF-kappaB pathway in the treatment

of inflammation and cancer. J Clin Invest. 107:135–142. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

van Vuuren SF: Antimicrobial activity of

South African medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 119:462–472.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bestwick CS and Milne L: Influence of

galangin on HL-60 cell proliferation and survival. Cancer Lett.

243:80–89. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sivakumar AS and Anuradha CV: Effect of

galangin supplementation on oxidative damage and inflammatory

changes in fructose-fed rat liver. Chem Biol Interact. 193:141–148.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kim HH, Bae Y and Kim SH: Galangin

attenuates mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation. Food Chem

Toxicol. 57:209–216. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zha WJ, Qian Y, Shen Y, Du Q, Chen FF, Wu

ZZ, Li X and Huang M: Galangin abrogates ovalbumin-induced airway

inflammation via negative regulation of NF-kappaB. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2013:7676892013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Huh JE, Jung IT, Choi J, Baek YH, Lee JD,

Park DS and Choi DY: The natural flavonoid galangin inhibits

osteoclastic bone destruction and osteoclastogenesis by suppressing

NF-κB in collagen-induced arthritis and bone marrow-derived

macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol. 698:57–66. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen S: Natural products triggering

biological targets-a review of the anti-inflammatory phytochemicals

targeting the arachidonic acid pathway in allergy asthma and

rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Drug Targets. 12:288–301. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wasserman AM: Diagnosis and management of

rheumatoid arthritis. Am Fam Physician. 84:1245–1252.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kapoor S, Fitzpatrick M, Clay E, Bayley R,

Wallace GR and Young SP: Metabolomics in the analysis of

inflammatory diseases. Roessner U: Metabolomics. Rijeka (HR):

InTech. Chapter 112012.

|

|

22

|

Yoshino S and Ohsawa M: The role of

lipopolysaccharide injected systemically in the reactivation of

collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 129:1309–1314.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Feldmann M, Brennan FM and Maini RN: Role

of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Annu Rev Immunol. 14:397–440.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gracie JA, Forsey RJ, Chan WL, Gilmour A,

Leung BP, Greer MR, Kennedy K, Carter R, Wei XQ, Xu D, et al: A

proinflammatory role for IL-18 in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin

Invest. 104:1393–1401. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Grabowski PS, Wright PK, Van't Hof RJ,

Helfrich MH, Ohshima H and Ralston SH: Immunolocalization of

inducible nitric oxide synthase in synovium and cartilage in

rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Br J Rheumatol.

36:651–655. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Schleimer RP: Inflammation: Basic

principles and clinical correlates edited by John Gallin, Ira

Goldstein and Ralph Snyderman, Raven Press, $219.00 (xvii + 995

pages) ISBN 0 88167 344 7. Immunol Today. 9:327, 19871988.

|

|

27

|

Anderson GD, Hauser SD, McGarity KL,

Bremer ME, Isakson PC and Gregory SA: Selective inhibition of

cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 reverses inflammation and expression of

COX-2 and interleukin 6 in rat adjuvant arthritis. J Clin Invest.

97:2672–2679. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hadjigogos K: The role of free radicals in

the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Panminerva Med. 45:7–13.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mansour RB, Lassoued S, Gargouri B, El

Gaïd A, Attia H and Fakhfakh F: Increased levels of autoantibodies

against catalase and superoxide dismutase associated with oxidative

stress in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus

erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 37:103–108. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|