Introduction

Pancreatic islet transplantation is a potential

treatment option for type 1 diabetes mellitus; however, the

shortage of human pancreas donors continues to restrict clinical

transplantation. The pig represents an alternative source of

unlimited organs and tissue, making xenotransplantation a potential

strategy for use in humans. However, xenogeneic rejection mediated

by T cell responses remains a major limitation to its clinical

application (1,2). Long-term survival of xenogeneic

islets in large animal models has been achieved with

immunosuppression (3,4); however, the high dose of

immunosuppressive agents required, accompanied by their side

effects (5,6), limits clinical application.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs), are critically important for

maintaining tolerance and controlling autoimmunity (7–9),

therefore they may represent an alternative and novel strategy for

achieving transplant tolerance. Previous studies have indicated

that adoptive transfer with ex vivo polyclonally expanded

human Tregs prevents islet xenograft rejection by suppressing

effector T cell responses (10),

and in vitro polyclonally expanded human Tregs maintain

their suppressive function in CD4+CD25−

effector T cells in a xenogeneic-stimulated mixed lymphocyte

reaction (11). These findings

indicate a possible strategy for overcoming cellular xenoresponses

in vitro and in vivo. However, a major limitation to

using polyclonally expanded Tregs is that they can cause

pan-immunosuppressive effects, leading to opportunistic infections

and tumor growth, due to their non-specific suppressive functions.

Studies in human and animal models have demonstrated that small

numbers of alloantigen-specific Tregs exhibit high efficiency to

prevent allograft rejection with fewer side effects (12–14).

Therefore, antigen-specific Tregs may hold immense promise for

human immunotherapy.

The present study investigated whether ex

vivo expanded human Tregs receiving xenoantigen stimulation are

more potent than polyclonally expanded Tregs in protecting against

islet xenograft rejection in NOD-SCID interleukin (IL)-2 receptor

(IL2r)γ−/− mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 3 newborn pigs (1 to 3 days old) supplied

by Chongqing Enservier Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Chongqing,

China) were used to isolate neonatal porcine islet cell clusters

(NICC). A total of 2 adult landrace pigs (male, 18 months old,

Chongqing Enservier Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) were used to

isolate porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cell as xenoantigen,

and were housed in separate cages at 20–26°C, 12-h light/dark cycle

with fresh air, and fed pig chow twice a day with free access to

water. NOD-SCID IL2rγ−/− mice (age, 6–8 weeks, weight,

25–30 g) were obtained from Chengdu Dashuo experimental animals Co.

Ltd. (Chengdu, Sichuan, China) and housed under specific

pathogen-free conditions (20–26°C, relative humidity, 40–70%, free

access to sterile feeds and sterile water and 12-h light/dark

cycle) in the approved Experimental Animal Center at Sichuan

University (Chengdu, China). The mice were used for porcine islet

transplantation. The procedures described in this study were

conducted according to the guidelines set by the Institute of

Laboratory Animals Resources Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

Guidebook) (15).

Porcine islet isolation and

transplantation

NICC were isolated from the pancreas of 1–3 day old

piglets and cultured for 6 days, as previously described (16). The NICC were pooled and 5,000

clusters (10) were transplanted

under the renal capsule of both kidneys of NOD-SCID

IL2rγ−/− mice.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

(PBMC) isolation and human Treg isolation

Human PBMCs were isolated from the blood of 4

healthy donors (age, 28–58; gender, 2 male and 2 female) by density

gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep™ (STEMCELL

Technologies China Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China).

CD4+CD25+CD127lo T cells were

isolated from PBMCs using the

CD4+CD25+CD127dim/− Regulatory T

Cell Isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach,

Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The purity of

CD4+CD25+CD127lo T cells was ≥98%.

Porcine PBMCs were isolated from heparinized whole blood of adult

landrace pigs by density gradient centrifugation using

Lymphoprep™ (STEMCELL Technologies China Co., Ltd.) and

used as xenogeneic stimulator cells. Human and animal studies were

approved by the Sichuan University Medical Ethics Committee and

Animal Research Ethics Communities. Written informed consent was

obtained from all donors.

In vitro expansion of human Tregs with

xenoantigen stimulation

To obtain large numbers of functional human Tregs

with xenoantigen specificity (Xeno-Treg) from

CD4+CD25+CD127lo T cells, cells

were harvested after 7 days of polyclonal stimulation and further

expanded for two subsequent cycles (7 days per cycle) by

stimulating with irradiated xenogeneic PBMCs. Polyclonal Tregs

(Poly-Treg) were solely expanded using CD3/CD28 beads.

CD4+CD25+CD127lo T

cells were expanded in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% human AB

serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 2 mM glutamine

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol

(2-ME) (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 100 U/ml

penicillin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 µg/ml

streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 100 nM

rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 37°C and 5%

CO2, in the presence of 400 U/ml IL-2 (Novartis

Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA) and Human T-Activator CD3/CD28

beads (Dynabeads®; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) in 96-well U-bottom plates (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes,

NJ, USA). After 7 days of expansion, Tregs were harvested and used

to induce Xeno-Treg. For both cycles of xenoantigen stimulation,

5×104 Tregs were cultured with 2×105

irradiated (30 Gy) porcine PBMCs (xenogeneic PBMC:Treg, 4:1), in

the presence of 5×104 Dynabeads®. The cells

were split and fresh medium was added every 3 days. After two

cycles of expansion, Treg were harvested for all subsequent

experiments.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were obtained from mouse

spleen or peripheral blood at 4-weeks, 9-weeks and 12-weeks

following NICC transplantation and were processed using red blood

cell lysis buffer (BioLegend, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), according

to the manufacturer's protocol. Human antigen CD45 (368503;

BioLegend, Inc.) was used for the flow cytometric analysis of human

leukocyte engraftment in the mouse spleen or peripheral blood cell

suspension. Human cells were surface stained with fluorescently

labeled antibodies specific for the human antigens CD4 (cat. nos.

317407 and 317425), CD25 (cat. nos. 302605 and 302613), CD127 (cat.

no. 351323), CD62L (cat. no. 304821), glucocorticoid-induced tumor

necrosis factor receptor-related protein (GITR; cat. no. 371223)

and HLA-DR (cat. no. 307617) (all from BioLegend, Inc.), in

staining buffer at 4°C for 30 min in the dark, followed by fixation

and permeabilization (Fix/Perm buffer; BioLegend, Inc.).

Intracellular staining was conducted with fluorescently labeled

anti-forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) (cat. no. 320105) and -cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4; cat. no. 369603) antibodies (both

BioLegend, Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. Flow cytometric

data were acquired using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences).

IL-10 analyses

Total RNA was extracted from Tregs using the RNeasy

Mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), according to the

manufacturer's protocol, followed by cDNA synthesis using the

SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis system (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(RT-qPCR) was performed on the Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) using the Platinum

SYBR Green qPCR Supermix-UDG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

reaction was 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 2 min followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 65°C for 35 sec. PCR primers specific

for human IL-10 were used: Sense 5′-GCCTAACATGCTTCGAGATC-3′ and

antisense 5′-GGGTTCAGGTACCGCTTCTC-3′. Human GAPDH primer (Sense

5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ and antisense

5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′) was used as an internal reference gene

and gene expression was normalized to GAPDH expression levels in

each PCR reaction (17).

IL-10 in the supernatants collected from Xeno-Treg

and Poly-Treg stimulation cultures was measured by ELISA, using the

IL-10 Human ELISA kit (cat. no. BMS215-2TEN; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

TCR Vβ CDR3 spectratyping

CDR3 spectratyping was performed as previously

described (18). Briefly, PCR

amplification of expanded human Tregs with xenoantigen stimulation

of polyclonal stimulation was performed until a plateau was

reached. For the 29 human TCR Vβ families, this required 36 PCR

amplification cycles, 29 TCR Vβ primers and a Fam-labeled Cβ

reverse primer (18). All the TCR

Vβ family primers were provided by Professor Stephen I. Alexander

(Centre for Kidney Research, The Children's Hospital at Westmead,

Sydney, NSW, Australia; Table I).

The PCR product (1 µl) from this reaction was mixed with 12 µl

Hi-Di™ Formamide and 0.2 µl GeneScan™ 500

TAMRA™ dye Size Standard in a 0.5 ml Genetic Analyzer sample tube

(all Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The sample was denatured by

heating at 95°C for 10 min and then rapidly cooled on ice. The

sample was then electrophoresed on the ABI Prism® 310

Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). An

electropherogram of the GeneScan-500 Size Standard was generated

under denaturing conditions on the ABI Prism® 310

Genetic Analyzer. Fragments were run using the POP-4™

Polymer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 60°C. When the size of

the PCR product was <500 bp, a capillary with dimensions of 47

cm × 50 µm i.d. (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used. If the

signal was too strong, the sample injection time or voltage was

decreased; or the sample was further diluted. The data were sized

and quantified using ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer with built in

software (ABI Prism 310 collection; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

| Table I.Primer sequences of TCR Vβ

families. |

Table I.

Primer sequences of TCR Vβ

families.

| Gene name | Oligonucleotide

sequence |

|---|

| BV2 |

GAAATCTCAGAGAAGTCTGAAATATTCG |

| BV3 |

CCTAAATCTCCAGACAAAGCTCACT |

| BV4 |

CCTGAATGCCCCAACAGC |

| BV5 |

ACCTGATCAAAACGAGAGGACAG |

| BV6 |

CTCTCCTGTGGGCAGGTCC |

| BV7-2 |

GTTTTTAATTTACTTCCAAGGCAACA |

| BV7-3 |

CAAGGCACGGGTGCG |

| BV7-6 |

ACTTACTTCAATTATGAAGCCCAACA |

| BV7-7 |

GAGTCATGCAACCCTTTATTGGTAT |

| BV7-8 |

AGGGGCCAGAGTTTCTGACTTAT |

| BV7-9 |

CTCAACTAGAAAAATCAAGGCTGCT |

| BV9 |

AACAGTTCCCTGACTTGCACTCT |

| BV10 |

TTCTTCTATGTGGCCCTTTGTCT |

| BV11 |

GGCTCAAAGGAGTAGACTCCACTCT |

| BV12 |

GGTGACAGAGATGGGACAAGAAGT |

| BV13 |

CATCTGATCAAAGAAAAGAGGGAAAC |

| BV14 |

AGAGTCTAAACAGGATGAGTCCGGTAT |

| BV15 |

AGAGTCTAAACAGGATGAGTCCGGTAT |

| BV16 |

AAACAGGTATGCCCAAGGAAAGA |

| BV18 |

CAGCCCAATGAAAGGACACAGT |

| BV19 |

GGGCAAGGGCTGAGATTGAT |

| BV20 |

AACCATGCAAGCCTGACCTT |

| BV23 |

TGTACCCCCGAAAAAGGACATAC |

| BV24 |

CAGTGTCTCTCGACAGGCACA |

| BV25 |

CTCAAACCATGGGCCATGA |

| BV27 |

CCAGAACCCAAGATACCTCATCAC |

| BV28 |

GGCTACGGCTGATCTATTTCTCA |

| BV29 |

GACGATCCAGTGTCAAGTCGATAG |

| BV30 |

CTGAGGTGCCCCAGAATCTCT |

| BC for BV |

CTGCTTCTGATGGCTCAAACA |

| BC for BV

probe |

6-FAMCACCCGAGGTCGCTMGBNFQ |

| BC forward |

TCCAGTTCTACGGGCTCTCG |

| BC reverse |

AGGATGGTGGCAGACAGGAC |

| BC probe |

6-FAMACGAGTGGACCCAGGATAGGGCCAA NFQ |

| GAPDH forward |

TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC |

| GAPDH reverse |

GGAAGGCCATGCCAGTGA |

| GAPDH probe |

VICCCTGGCCAAGGTCATCCATGACAACTTTAMRA |

In vitro Treg suppression assay

The suppressive capacity of Tregs was assessed by

measuring inhibition of proliferation in mixed leukocyte reaction

(MLR) assays. Proliferation was evaluated using the

CellTrace™ Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)

Cell Proliferation kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Responder cells (human PBMCs) were labeled with 0.5 µM CFSE

(Molecular Probes; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) prior to

stimulation. CFSE-labeled responder cells (1×105) from

autologous Treg donors were stimulated with 2×105

irradiated xenogeneic stimulator PBMCs or purified anti-human CD3

antibody (BD Biosciences). Tregs were titrated into the cultures at

different ratios. After 7 days of culture, the proliferation of

responder cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (LSR II; BD

Biosciences).

Adoptive transfer of human cells

Adoptive transfer of human cells was performed as

previously described (10). Human

PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy donors. A total of

1×107 CD25+ cell-depleted PBMCs with or

without 1×106 autologous ex vivo expanded human

Xeno-Treg or Poly-Treg were injected intravenously into NOD-SCID

IL2rγ−/− mice 3 days after NICC transplantation.

Peripheral blood, spleen and NICC grafts were collected from

recipient mice at predetermined time points to analyze human

leukocyte engraftment and NICC graft survival. Graft rejection was

defined as no visible intact graft observed by histological

examination (19).

Histology and

immunohistochemistry

Histology and immunohistochemistry of cryostat

section (6–8 µm) were undertaken as described previously (10). Porcine endocrine cells were

detected using anti-porcine insulin antibody (IR00261-2 insulin;

1:100; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) and

the VECTASTAIN® ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.,

Burlingame, CA, USA). Graft-infiltrating human leukocytes were

stained using anti-human CD45 antibody (14-9457-82; 1:200;

eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by

incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary rabbit

anti-mouse antibody (31451; 1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

then analyze using a Zeiss microscope (AX10; Zeiss AG, Oberkochen,

Germany).

Statistical analysis

Results comparisons involving two groups were

analyzed using Student's t-test (two-tailed) and those involving

multiple groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance

with the Tukey multiple comparison test by SPSS version 22 (IBM

Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Graft survival was evaluated using

Kaplan-Meier analysis. The data were presented as the means ±

standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Human Tregs expanded ex vivo with

xenoantigen stimulation retain Treg phenotype and secrete

IL-10

The phenotype of Xeno-Treg was examined by flow

cytometry. After two cycles of xenoantigen stimulation, Xeno-Treg

retained the classic Treg phenotype, as did Poly-Treg, which is

characterized by high levels of CD25, Foxp3, CTLA-4, CD62L and GITR

expression, and very low or undetectable CD127 expression (Fig. 1). However, compared with Poly-Treg,

Xeno-Treg expressed more HLA-DR, which has been described as an

effector marker of Treg (20,21)

(Fig. 1).

| Figure 1.Phenotypic characterization of

expanded Tregs. Gates were set on CD4+CD25+

cells. Cell surface expression of CD25, CD127, CD62L, GITR and

HLA-DR, and intracellular expression of Foxp3 and CTLA-4 in

Xeno-Treg or Poly-Treg are presented as the percentage of

CD4+CD25+ cells co-expressing individual Treg

markers examined. Data presented in figures represent the

percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells co-expressing

individual Treg markers tested. Data are representative of three

independent experiments. CD, cluster of differentiation; CTLA-4,

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4; FoxP3, forkhead box P3; GITR,

glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-related

protein; HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen-DR; Poly-Treg, polyclonal

Treg; Tregs, regulatory T cells; Xeno-Treg, Treg with xenoantigen

specificity. |

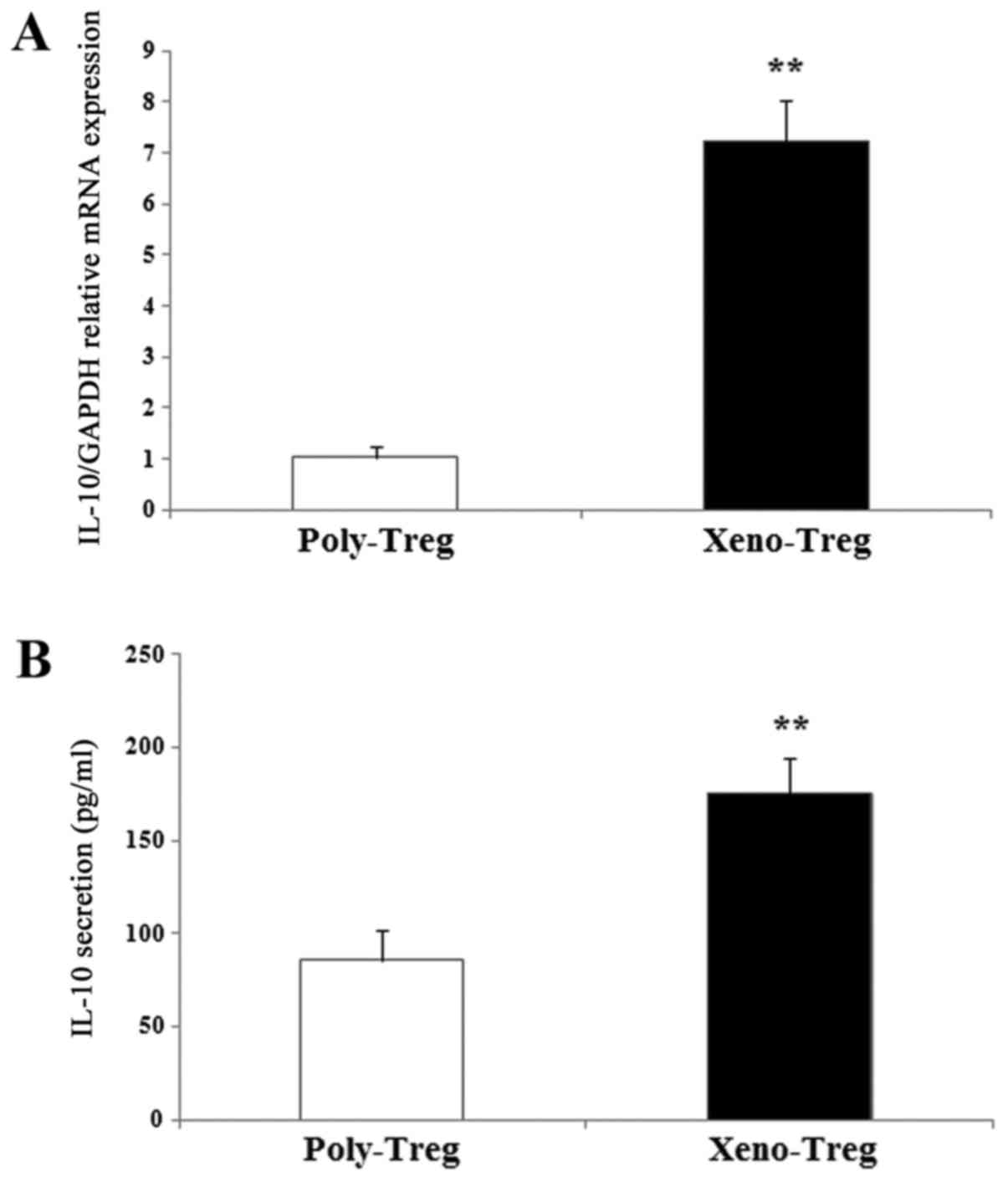

IL-10 expression in Tregs was assessed by RT-qPCR.

Xenoantigen stimulation led to an upregulation of IL-10 expression,

with expression levels 7-fold higher compared with Poly-Treg

(Fig. 2A; P<0.01). In addition,

IL-10 secretion was measured in the cell culture supernatants of

Tregs receiving xenoantigen or polyclonal stimulation. Consistent

with mRNA expression, IL-10 secretion by Xeno-Treg was enhanced

compared with Poly-Treg (Xeno-Treg: 175±18.9 pg/ml vs. Poly-Treg:

86±16.4 pg/ml; Fig. 2B;

P<0.01). These results demonstrated that Xeno-Treg may retain a

Treg phenotype, but secrete higher levels of IL-10 compared with

Poly-Treg, which may result in greater suppressive potency.

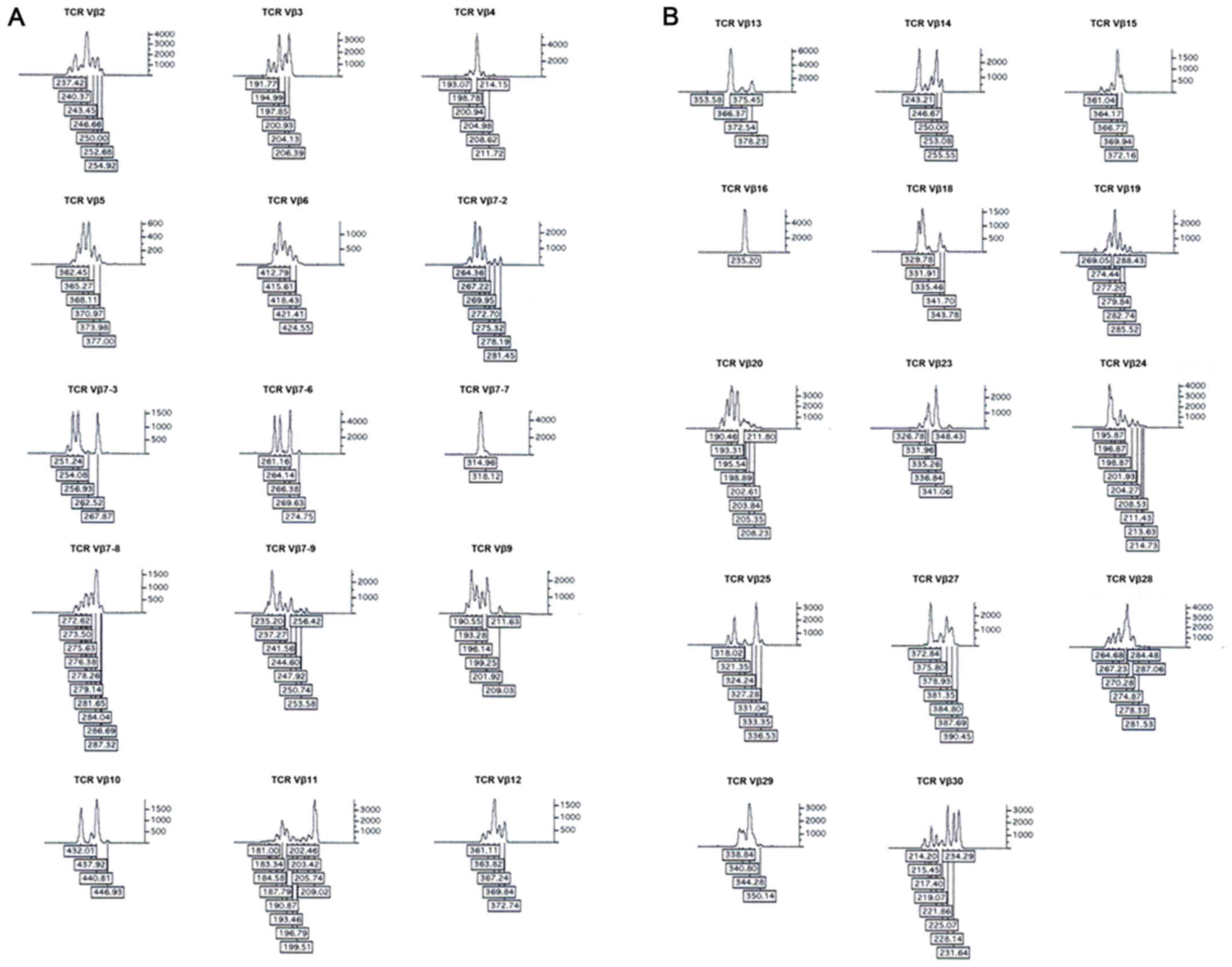

Tregs exhibit restricted TCR Vβ

repertoire following xenoantigen stimulation

Spectratyping was used to analyze the TCR Vβ

families at the CDR3 level and screen for clonal expansion of

specific T cells (22–24). All 29 TCR Vβ families were detected

in Xeno-Treg or Poly-Treg, and in control CD4+ T cells.

However, there were altered TCR Vβ repertoires in both Xeno-Treg

and Poly-Treg compared with in CD4+ T cells. Increased

expression of TCR Vβ4, Vβ7-9, Vβ20, Vβ28 (>5% in repertoire) and

TCR Vβ10 and Vβ18 were observed in Xeno-Treg and Poly-Treg compared

with in CD4+ T cells (Fig.

3). In addition, expression levels of TCR Vβ4, Vβ10, Vβ18 and

Vβ20 were markedly increased in Xeno-Treg compared with in

Poly-Treg (Fig. 3).

Overall spectratyping of PCR products revealed a

restricted TCR Vβ repertoire in Xeno-Treg and Poly-Treg compared

with in CD4+ T cells, which possessed a diverse TCR Vβ

repertoire. Nearly all the TCR Vβ families exhibited a Gaussian

distribution, with the exception of TCR Vβ3, Vβ7-7, Vβ19 and Vβ23

(Fig. 4). Spectratypes of TCR Vβ4,

Vβ20 and Vβ28 (>5% of the TCR Vβ repertoire and increased

expression) in Xeno-Treg and Poly-Treg demonstrated restriction and

expanded clone at size 205, 196 and 274, respectively (Figs. 5 and 6). Spectratypes of TCR Vβ7–9 (>5% of

the TCR Vβ repertoire and increased expression) exhibited

restriction and expanded clone at size 234 in Poly-Treg and at size

237 in Xeno-Treg. In addition, spectratypes of TCR Vβ10 (<5% of

the TCR Vβ repertoire and increased expression) possessed

restriction and expanded clone at size 432 in Poly-Treg and at size

432 and 441 in Xeno-Treg.

Human Tregs expanded ex vivo with

xenoantigen stimulation exhibit enhanced suppressive capacity

To determine whether Xeno-Treg possessed more potent

and xenoantigen-specific suppressive capacity against xenoimmune

responses compared with Poly-Treg, their suppressive function was

assessed in an MLR assay using CFSE-labeled PBMCs as responder

cells. In a xenoantigen-driven MLR (Xeno MLR) assay, Xeno-Treg

exhibited an enhanced xenoantigen-specific suppressive capacity

compared with Poly-Treg, as evidenced by the ~55 and 45%

suppression of responder cell proliferation at low responder cell:

Treg ratios of 1:1/8 and 1:1/16, respectively (Fig. 7A). Even at a higher responder cell:

Treg ratio of 1:1/32, Xeno-Treg still demonstrated >35%

suppression of responder cell proliferation, which was 2.5-fold

higher compared with Poly-Treg (Fig.

7A). These data revealed that Xeno-Treg possess enhanced and

xenoantigen-specific suppressive capacity. However, both Xeno- and

Poly-Treg demonstrated similar ability to suppress responder cell

proliferation in a polyclonally-stimulated MLR (Poly MLR) assay

(Fig. 7B), thus suggesting that

xenoantigen stimulation did not alter the capacity to suppress

polyclonally-stimulated responses.

Human Treg expanded ex vivo with

xenoantigen stimulation prevent rejection of porcine islet

xenografts

To determine the in vivo suppressive capacity

of ex vivo expanded Xeno-Treg, a total of 1×107

CD25+ cell-depleted PBMCs with or without

1×106 autologous ex vivo expanded Xeno-Treg or

Poly-Treg were injected intravenously into NOD-SCID

IL2rγ−/− mice 3 days after NICC transplantation.

Nonreconstituted mice were used as a control. Mice that were

reconstituted with human PBMCs, rejected their xenografts

completely within 28 days of transplantation, whereas NICC grafts

survived for ≥84 days in nonreconstituted recipients (Fig. 8A). In mice reconstituted with

Xeno-Treg and PBMCs (Xeno-Treg:PBMC ratio of 1:10), 75% of NICC

xenografts survived beyond 84 days (Fig. 8A). In contrast, in mice

reconstituted with Poly-Treg and PBMCs (Poly-Treg:PBMC ratio of

1:10), 75% of NICC xenografts survived ≥48 days, 25% of NICC

xenografts survived until day 56, and all xenografts were rejected

by day 63 (Fig. 8A). These results

suggested that Xeno-Treg may prolong NICC xenograft survival.

| Figure 8.Xeno-Treg suppress rejection of islet

xenografts in humanized mice. (A) Percentage of graft survival in

mice administered 1×107 CD25+ cell-depleted

human PBMCs with or without 1×106 Poly-Treg or

Xeno-Treg. Graft survival was monitored 18, 21, 28, 48, 56, 63 and

84 days post cell transfer. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of the

percentage of human leukocyte engraftment in the spleen and

peripheral blood of NOD-SCID interleukin-2 receptor γ−/−

mice after PBMC plus Treg adoptive transfer. Data were acquired on

day 63 for Poly-Treg or day 84 for Xeno-Treg. Data are presented as

the means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

CD, cluster of differentiation; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear

cell; Poly-Treg, polyclonal Treg; Tregs, regulatory T cells;

Xeno-Treg, Treg with xenoantigen specificity. |

Human leukocyte engraftment was confirmed by flow

cytometry. Following human Poly-Treg and PBMC adoptive transfer,

the spleen and peripheral blood was engrafted with 27.3±6.3 and

14.7±4.2% of human CD45+ cells respectively, by day 63

(Fig. 8B). However, following

human Xeno-Treg and PBMC adoptive transfer, the spleen and

peripheral blood was engrafted with 15.2±3.8 and 10.5±3.2% of human

CD45+ cells respectively, by day 84 (Fig. 8B). Decreased engraftment of human

CD45+ cells in mice reconstituted with Xeno-Treg and

PBMCs may indicate that graft survival is as a result of

xenoantigen-specific Treg-mediated suppression and not due to

engraftment failure.

Immunohistochemistry of NICC grafts from

nonreconstituted recipients revealed intact insulin-positive cells

with no CD45+ cells infiltration (Fig. 9A-C). Numerous graft-infiltrating

human CD45+ cells were detected in the rejected

xenografts from PBMC-reconstituted mice; however, no

insulin-positive cells were visible (Fig. 9D-F). Long-term surviving grafts

from Xeno-Treg- and PBMC-reconstituted mice contained intact

insulin-secreting cells surrounded by a small number of human

CD45+ cells (Fig.

9G-I). On day 63, immunohistochemistry of NICC grafts from

Poly-Treg- and PBMC-reconstituted mice revealed small, damaged and

insulin-positive cells with numerous graft-infiltrating human

CD45+ cells (Fig.

9J-L). These results suggested that adoptive transfer of ex

vivo expanded Xeno-Treg may possess a greater capacity to

reduce xenograft damage and prevent rejection of porcine islet

xenografts compared with Poly-Treg.

| Figure 9.Histology and immunohistochemical

analysis of NICC xenografts. Representative hematoxylin and eosin

staining images; and immunohistochemical staining images of porcine

insulin and human CD45 in NICC xenograft samples from mice

receiving (A-C) no human cells (NICC alone 84 days

post-transplantation), (D-F) only human PBMCs (NICC + PBMC 28 days

post-PBMC transfer), (G-I) human PBMCs and Xeno-Treg (NICC + PBMC +

Xeno-Treg 84 days post-cell transfer) or (J-L) human PBMCs and

Poly-Treg (NICC + PBMC + Poly-Treg 63 days post-cell transfer). (A,

B, E-I, K and L) Magnification, ×200; (C, D and J) magnification,

×100. CD, cluster of differentiation; NICC, neonatal porcine islet

cell clusters; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; Poly-Treg,

polyclonal Treg; Tregs, regulatory T cells; Xeno-Treg, Treg with

xenoantigen specificity. |

Discussion

The use of efficient antigen-specific Tregs may

reduce the number of Tregs required for therapy and lower the risk

of systemic immunosuppression (25,26).

Numerous studies have investigated strategies for large-scale

expansion of alloantigen-specific human Tregs (27–29),

and ex vivo alloantigen-specific Tregs were shown to possess

enhanced suppressive capacity in allogeneic responses in

vitro and in vivo (30,31).

In the present study, a strategy using one cycle of polyclonal

stimulation followed by two subsequent cycles of xenoantigen

stimulation was developed to selectively expand Xeno-Treg.

Following stimulation, spectratyping was conducted to analyze the

TCR Vβ families of Tregs at the CDR3 level and screen for clonal

expansion of specific T cells. CDR3 spectratyping is a

well-described method for measuring oligoclonality within T cell

populations (32). Normal PBMC

samples of a single Vβ family display a Gaussian distribution of

6–11 peaks, each separated by three nucleotides. Each peak

corresponds to a TCR transcript with a given CDR3 length that may

contain numerous sequences (32).

The number of TCR transcripts with a specific CDR3 length is

proportional to the area under each peak. An increase in the height

and area of a size peak typically indicates oligoclonal or

monoclonal expansion in the polyclonal T cell background.

Oligoclonal T cells give fewer peaks in a restricted distribution.

Single clones give a single peak. This method has been used

previously to screen PCR products in an efficient manner for

possible T cell clonal expansion following MLR, renal biopsies and

urine at the time of rejection (22,33).

The present study identified an increase in the expression of TCR

Vβ4, TCR Vβ10, TCR Vβ18 and TCR Vβ20 families for Xeno-Treg

compared with Poly-Treg. In addition, spectratypes of TCR Vβ4,

Vβ10, Vβ18 and Vβ20 in Xeno-Treg demonstrated restriction and

expanded clone at size 205, 441, 332 and 196, respectively, which

indicated that Treg acquired xenoantigen specificity following

xenoantigen stimulation by identifying the specific expanded clones

in TCR Vβ families. Furthermore, Xeno-Treg were acquired and showed

enhanced suppressive capacity in the xenoimmune response detected

in a MLR.

The mechanisms underlying human xenoantigen-specific

Treg suppressive functions in vivo remain largely unknown.

Previous studies have revealed that IL-10 serves a critical role in

Treg-mediated suppression of xenogeneic responses in vivo

and in vitro (10,34,35).

In the present study, Xeno-Treg upregulated the expression of IL-10

and produced more IL-10, compared with Poly-Treg, in the culture

medium. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that the suppressive

functions of Xeno-Treg in the Xeno MLR assay are mediated by IL-10.

Furthermore, the results demonstrated that Xeno-Treg expressed

increased levels of HLA-DR, thus suggesting that IL-10 secretion of

Xeno-Treg was associated with the upregulated effector marker. Yi

et al demonstrated that adoptive transfer with expanded

autologous Tregs prevents islet xenograft rejection in human

PBMC-reconstituted mice, by inhibiting graft infiltration of

effector cells and their function via IL-10 (10). In the present study, NOD-SCID

IL2rγ−/− mice reconstituted with Xeno-Treg and PBMCs at

a Xeno-Treg:PBMC ratio of 1:10; 75% of NICC xenografts contained

intact insulin-secreting cells, which survived beyond 84 days

compared with the Poly-Treg- and PBMC-reconstituted group, in which

75% of NICC xenografts survived to day 48 and by day 63 all

xenografts showed small, damaged and insulin positive-staining

cells, with a large number of graft-infiltrating human

CD45+ cells. These findings suggested that adoptively

transferred ex vivo expanded Xeno-Treg may display a greater

capacity to reduce xenograft damage and prevent porcine islet

xenograft rejection compared with Poly-Treg. However, the

mechanisms of human xenoantigen-specific Treg suppressive function

in vivo remain largely unknown. Further studies are required

to explore whether IL-10 has an important role in human

xenoantigen-specific Treg suppressive function in vivo.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

adoptive transfer with ex vivo expanded Xeno-Treg exhibited

a greater capacity to prevent islet xenograft rejection in

humanized NOD-SCID IL2rγ−/− mice compared with

Poly-Treg, thus suggesting a novel strategy for adoptive Treg cell

therapy for immunomodulation in islet xenotransplantation that may

minimize systemic immunosuppression.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Shounan Yi

from the Centre for Transplant and Renal Research of Westmead

Millennium Institute in the University of Sydney for his expert

technical assistance.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81501602

and 81271712), the Science and Technology Project of the Health

Planning Committee of Sichuan (grant no. 17PJ483) and the Hunan

Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

14JJ2039).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

XJ contributed to the design of the present study,

data analysis, and helped draft the manuscript. MH conducted the

TCR Vβ CDR3 spectratyping and analyzed the data. LG contributed to

the animal work and performed the immunohistochemistry. HFL and YW

performed the flow cytometry. MJ participated in the Treg

suppression assay and revised the article. HL helped to design the

present study and with the data analysis, and participated in

reviewing and revising the article.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All human and animal studies were approved by the

Sichuan University Medical Ethics Committee and Animal research

Ethics communities. All donors provided informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all

donors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Vadori M and Cozzi E: The immunological

barriers to xenotransplantation. Tissue Antigens. 86:239–253. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Butler JR, Wang ZY, Martens GR, Ladowski

JM, Li P, Tector M and Tector AJ: Modified glycan models of

pig-to-human xenotransplantation do not enhance the human-anti-pig

T cell response. Transpl Immunol. 35:47–51. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shin JS, Kim JM, Min BH, Yoon IH, Kim HJ,

Kim JS, Kim YH, Kang SJ, Kim J, Kang HJ, et al: Pre-clinical

results in pig-to-non-human primate islet xenotransplantation using

anti-CD40 antibody (2C10R4)-based immunosuppression.

Xenotransplantation. 25:2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lee JI, Kim J, Choi YJ, Park HJ, Park HJ,

Wi HJ, Yoon S, Shin JS, Park JK, Jung KC, et al: The effect of

epitope-based ligation of ICAM-1 on survival and retransplantation

of pig islets in nonhuman primates. Xenotransplantation. 25:2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Qiu F, Liu H, Liang CL, Nie GD and Dai Z:

A new immunosuppressive molecule emodin induces both

CD4+FoxP3+ and

CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells and suppresses

murine allograft rejection. Front Immunol. 8:15192017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Garakani R and Saidi RF: Recent progress

in cell therapy in solid organ transplantation. Int J Organ

Transplant Med. 8:125–131. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Marek-Trzonkowska N, Myśliwiec M,

Iwaszkiewicz-Grześ D, Gliwiński M, Derkowska I, Żalińska M,

Zieliński M, Grabowska M, Zielińska H, Piekarska K, et al: Factors

affecting long-term efficacy of T regulatory cell-based therapy in

type 1 diabetes. J Transl Med. 14:3322016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kasper IR, Apostolidis SA, Sharabi A and

Tsokos GC: Empowering regulatory T cells in autoimmunity. Trends

Mol Med. 22:784–797. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lu L, Barbi J and Pan F: The regulation of

immune tolerance by FOXP3. Nat Rev Immunol. 17:703–717. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yi S, Ji M, Wu J, Ma X, Phillips P,

Hawthorne WJ and O'Connell PJ: Adoptive transfer with in vitro

expanded human regulatory T cells protects against porcine islet

xenograft rejection via interleukin-10 in humanized mice. Diabetes.

61:1180–1191. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jin X, Wang Y, Hawthorne WJ, Hu M, Yi S

and O'Connell P: Enhanced suppression of the xenogeneic T-cell

response in vitro by xenoantigen stimulated and expanded regulatory

T cells. Transplantation. 97:30–38. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dawson NAJ, Vent-Schmidt J and Levings MK:

Engineered tolerance: Tailoring development, function, and

antigen-specificity of regulatory T cells. Front Immunol.

8:14602017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Moore C, Tejon G, Fuentes C, Hidalgo Y,

Bono MR, Maldonado P, Fernandez R, Wood KJ, Fierro JA, Rosemblatt

M, et al: Alloreactive regulatory T cells generated with retinoic

acid prevent skin allograft rejection. Eur J Immunol. 45:452–463.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sagoo P, Lombardi G and Lechler RI:

Relevance of regulatory T cell promotion of donor-specific

tolerance in solid organ transplantation. Front Immunol. 3:1842012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

The OLAW office of NIH, . Institutional

animal care and use committee guidebook. 2nd. 2002

|

|

16

|

Korbutt GS, Elliott JF, Ao Z, Smith DK,

Warnock GL and Rajotte RV: Large scale isolation, growth, and

function of porcine neonatal islet cells. J Clin Invest.

97:2119–2129. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Walters G and Alexander SI: T cell

receptor BV repertoires using real time PCR: A comparison of SYBR

green and a dual-labelled HuTrec fluorescent probe. J Immunol

Methods. 294:43–52. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yi S, Hawthorne WJ, Lehnert AM, Ha H, Wong

JK, van Rooijen N, Davey K, Patel AT, Walters SN, Chandra A and

O'Connell PJ: T cell-activated macrophages are capable of both

recognition and rejection of pancreatic islet xenografts. J

Immunol. 170:2750–2758. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Baecher-Allan C, Wolf E and Hafler DA: MHC

class II expression identifies functionally distinct human

regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 176:4622–4631. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fountoulakis S, Vartholomatos G, Kolaitis

N, Frillingos S, Philippou G and Tsatsoulis A: HLA-DR expressing

peripheral T regulatory cells in newly diagnosed patients with

different forms of autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid.

18:1195–1200. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gagne K, Brouard S, Giral M, Sebille F,

Moreau A, Guillet M, Bignon JD, Imbert BM, Cuturi MC and Soulillou

JP: Highly altered V beta repertoire of T cells infiltrating

long-term rejected kidney allografts. J Immunol. 164:1553–1563.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Baron C, McMorrow I, Sachs DH and LeGuern

C: Persistence of dominant T cell clones in accepted solid organ

transplants. J Immunol. 167:4154–4160. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Walters G, Habib AM, Reynolds J, Wu H,

Knight JF and Pusey CD: Glomerular T cells are of restricted

clonality and express multiple CDR3 motifs across different Vbeta

T-cell receptor families in experimental autoimmune

glomerulonephritis. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 98:e71–e81. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Adair PR, Kim YC, Zhang AH, Yoon J and

Scott DW: Human tregs made antigen specific by gene modification:

The power to treat autoimmunity and antidrug antibodies with

precision. Front Immunol. 8:11172017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ma B, Yang JY, Song WJ, Ding R, Zhang ZC,

Ji HC, Zhang X, Wang JL, Yang XS, Tao KS, et al: Combining exosomes

derived from immature DCs with donor antigen-specific treg cells

induces tolerance in a rat liver allograft model. Sci Rep.

6:329712016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zheng J, Liu Y, Qin G, Chan PL, Mao H, Lam

KT, Lewis DB, Lau YL and Tu W: Efficient induction and expansion of

human alloantigen-specific CD8 regulatory T cells from naive

precursors by CD40-activated B cells. J Immunol. 183:3742–3750.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Veerapathran A, Pidala J, Beato F, Yu XZ

and Anasetti C: Ex vivo expansion of human Tregs specific for

alloantigens presented directly or indirectly. Blood.

118:5671–5680. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Cheraï M, Hamel Y, Baillou C, Touil S,

Guillot-Delost M, Charlotte F, Kossir L, Simonin G, Maury S, Cohen

JL and Lemoine FM: Generation of human alloantigen-specific

regulatory T cells under good manufacturing practice-compliant

conditions for cell therapy. Cell Transplant. 24:2527–2540. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Peters JH, Hilbrands LB, Koenen HJ and

Joosten I: Ex vivo generation of human alloantigen-specific

regulatory T cells from CD4(pos)CD25(high) T cells for

immunotherapy. PLoS One. 3:e22332008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Boardman DA, Philippeos C, Fruhwirth GO,

Ibrahim MA, Hannen RF, Cooper D, Marelli-Berg FM, Watt FM, Lechler

RI, Maher J, et al: Expression of a chimeric antigen receptor

specific for donor HLA class I enhances the potency of human

regulatory T cells in preventing human skin transplant rejection.

Am J Transplant. 17:931–943. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Fozza C, Barraqueddu F, Corda G, Contini

S, Virdis P, Dore F, Bonfigli S and Longinotti M: Study of the

T-cell receptor repertoire by CDR3 spectratyping. J Immunol

Methods. 440:1–11. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Alvarez CM, Opelz G, Giraldo MC, Pelzl S,

Renner F, Weimer R, Schmidt J, Arbeláez M, García LF and Süsal C:

Evaluation of T-cell receptor repertoires in patients with

long-term renal allograft survival. Am J Transplant. 5:746–756.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li M, Eckl J, Abicht JM, Mayr T, Reichart

B, Schendel DJ and Pohla H: Induction of porcine-specific

regulatory T cells with high specificity and expression of IL-10

and TGF-β1 using baboon-derived tolerogenic dendritic cells.

Xenotransplantation. 25:2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Li M, Eckl J, Geiger C, Schendel DJ and

Pohla H: A novel and effective method to generate human

porcine-specific regulatory T cells with high expression of IL-10,

TGF-β1 and IL-35. Sci Rep. 7:39742017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|