Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed

malignancy in women worldwide and the second leading cause of

cancer-associated mortality in women after lung cancer; breast

cancer is responsible for over one million of the estimated 10

million neoplasms diagnosed worldwide each year in both sexes

(1,2). Breast cancer is commonly treated with

anti-estrogens, surgical resection, radiotherapy and chemotherapy

(3,4). Tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors,

metformin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin are widely used in

the treatment of breast cancer (5). However, these drugs not only kill

cancer cells, but also affect human normal cells. Thus, there is an

imperative need to develop more effective and less toxic antitumor

drugs.

Inducing cancer cell apoptosis via chemotherapy is a

commonly used method in the treatment of various different types of

cancer. Apoptosis targets that are currently being investigated for

chemotherapy include the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK),

signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) and

NF-κB signaling pathways (6,7). The

MAPK signaling pathways include extracellular-signal-regulated

kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38, which regulate

a variety of cellular behaviors (8). JNK and p38 are activated in response

to several stress signals and are associated with the induction of

apoptosis. ERK can antagonize apoptosis by phosphorylating

pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated death promoter (Bax) and

anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, and inhibiting their functions

(9). Numerous studies have

revealed that STAT3 expression is higher in tumor tissues compared

with in normal tissues, and its prolonged activation is associated

with a number of different types of malignancy (10). NF-κB, a family of signal-responsive

transcription factors, can be maintained in an inactive state

within the cytoplasm through interactions and binding to inhibitor

of κB (i-κB) proteins in normal cells, and has been demonstrated to

be activated in cancer cells, including prostate and lung cancer

(11,12). These pathways may be triggered in

response to extra- or intracellular stimuli, such as reactive

oxygen species (ROS) (13).

ROS is an important second messenger in apoptosis

and cell signaling (14), and high

ROS levels have been suggested to activate intrinsic pathways and

induce cell apoptosis (15). A

number of studies have used oxidation therapy to treat patients

with cancer through increasing ROS generation to induce cancer cell

apoptosis (16–19) Therefore, ROS are highly promising

drug targets for cancer therapy.

Quinalizarin is an anthraquinone component isolated

from Rubiaceae; its anthraquinone ring is similar to the

nuclei of antitumor drugs such as doxorubicin and daunorubicin

(20). Previous studies have

demonstrated that it promotes apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells,

AGS gastric cancer cells, and Huh 7 hepatoma cells via the MAPK and

STAT3 signaling pathways (21,22).

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are currently no

detailed reports describing the effects of quinalizarin in human

breast cancer.

In the present study, in order to determine whether

quinalizarin induced human breast cancer cell mortality and

decreased normal cells toxicity, the cytotoxic effects, apoptotic

effects, cell cycle, ROS effects and key molecular signaling

proteins involved in regulation of apoptosis were investigated in

human breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

In the present study, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; MedChem

Express) was dissolved in 20 mM 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Quinalizarin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was prepared as a stock

solution in DMSO and stored at −20°C until use.

Cell cultures

Human breast cancer estrogen-dependent cell lines

(MCF-7, T47D and MDA-MB231) were purchased from the American Type

Culture Collection and normal human cells (L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T)

were obtained from Sai Qi (Shanghai) Biological Engineering Co.,

Ltd. The human normal liver cells (L-02), human lung fibroblast

cells (IMR-90) and normal kidney epithelial cells (293-T) were used

as controls as the liver and kidneys are major target organs for

drug toxicity testing, and IMR-90 cells have not transformed from

embryonic cells, which can directly reflect the effects of toxicity

in toxicity studies. MCF-7, T47D and MDA-MB231 cells were grown in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T cells were grown in

RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 100

µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and

incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h.

MTT assay

MCF-7, T47D, MDA-MB231, L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T cells

were harvested in the logarithmic growth phase and then seeded in

96-well culture plates at a density of 6×103 cells/per

well. After 24-h incubation at 37°C, the cells were treated with

different concentrations (1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 µmol/l) of 5-FU or

quinalizarin for 24 h. Cells in the control group were treated with

DMSO. The cells were then incubated with 20 µl MTT (5 mg/ml) for 2

h at 37°C. The intracellular formazan crystals were solubilized

with 100 µl DMSO and incubated for 15 min at 37°C, after which the

absorbance of the solutions was measured at 490 nm (BioTek

Instruments, Inc.). The half maximal inhibitory concentration

(IC50) values were calculated using GraphPad Prism

version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Hoechst 33324 staining

Apoptosis was analyzed using Hoechst 33324 (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) staining. MCF-7 cells were seeded onto

cell slides in 6-well plates (1×105 cells/per well) and

treated with 10 µmol/l 5-FU or 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12

and 24 h at 37°C. After washing twice with PBS, cells were

resuspended in 5 µl Hoechst 33324 binding buffer, and dual staining

was performed with 5 µl propidium iodide (PI; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were incubated with Hoechst

33324 stain for 5 min at 37°C and observed under a fluorescence

microscope DM 2500 (Leica Microsystems GmbH) at magnification,

×400.

Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC)/PI double staining and flow cytometry

Early and late apoptosis were analyzed by flow

cytometry. MCF-7 cells were seeded onto cell slides in 6-well

plates (1×105 cells/well) and treated with 10 µmol/l

5-FU or 10 µmol/l quinalizarin at 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, as

aforementioned. Cells were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min at

4°C and washed three times with PBS. A total of 10 µl FITC and 5 µl

PI were incubated with the cell suspension for 20 min at 37°C in

the dark and analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Inc.

Brea, CA, USA). CytExpert software 2.0 (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) was

used for analysis.

Cell cycle analysis

MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin

for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h at a density of 1×105 cells/per

well. Subsequently, the cell culture RPMI-1640 medium (10% FBS; 100

U/ml penicillin; 100 µg/ml streptomycin) was removed, and the cells

were trypsinized (0.05% trypsin-EDTA in PBS), washed twice with

cold PBS and fixed in 70% ethanol for 12 h at −20°C. Cell

suspensions were then incubated with RNase A and PI (both Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. The

stained cells were analyzed for DNA content using flow cytometry

(Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The cell cycle was analyzed using

CytExpert software 2.0 (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Western blot analysis

MCF-7 cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with FR180204

(ERK inhibitor, 12 µmol/liter) or SP600125 (JNK inhibitor, 12

µmol/liter) or SB203580 (p38 inhibitor, 12 µmol/liter) (MedChem

Express) dissolved in PBS and then treated with 10 µmol/l

quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12 or 24 h. Proteins were extracted with

cell lysis buffer (1 M HEPES, pH 7.0; 5 M NaCl; 0.5% Triton X-100;

10% glycerol; 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol; 20 mg/ml AEBSF; 0.5 mg/ml

pepstatin; 0.5 mg/ml leupeptin; and 2 mg/ml aprotinin) for 30 min

at 37°C and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The

protein concentration was quantified using Coomassie blue staining.

Equivalent proteins (30 µg) were separated via SDS-PAGE (8–12% gel)

and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, which were incubated

in blocking solution [fresh 5% non-fat milk in 10 mM Tris-HCl

containing 150 mM NaCl and Tris-buffered saline (TBS); pH 7.5] and

TBS+0.2% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes

were incubated for 12 h at 4°C with the following primary

antibodies: Mouse monoclonal antibodies against α-tubulin (1:2,500;

cat. no. sc-8035; internal control), Bax (1:1,500; cat. no.

sc-493), Bcl-2 (1:1,500; cat. no. sc-7382), caspase-3 (1:1,500;

cat. no. sc-373730), cleaved (cle)-poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

(PARP; 1:1,500; cat. no. sc-8007), phosphorylated (p)-JNK

(Tyr183 and Tyr185; 1:1,500; cat. no.

sc-6254), JNK (1:1,500; cat. no. sc-7345), p-p38

(Tyr182; 1:1,500; cat. no. sc-7973), p-ERK

(Tyr204; 1:1,500; cat. no. sc-8059), p-STAT3

(Tyr705; 1:1,500; cat. no. sc-8059) and STAT3 (1:1,500;

cat. no. sc-8019); and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CDK1/2

(1:2,500; cat. no. sc-163), cyclin B1 (1:2,500; cat. no. sc-4073),

p27 (1:2,500; cat. no. sc-528), p21 (1:1,500; cat. no. sc-397),

ERK2 (1:1,500; cat. no. sc-154), p38α/β (1:1,500; cat. no.

sc-7194), NF-κB (1:2,500; cat. no. sc-1190) and IκB (1:2,500; cat.

no. sc-7977; all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The

membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated

anti mouse (1:5,000; cat. no. ZB 2301) and anti rabbit (1:5,000;

cat. no. ZB 2305; both from OriGene Technologies, Inc.) secondary

antibodies for 2 3 h at room temperature followed by washing with

TBST. Proteins were visualized using Pierce ECL Western Blotting

Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the AI600

chemiluminescence imager (GE Healthcare), and were semi-quantified

using ImageJ software (version 1.46r; National Institutes of

Health). Protein levels were normalized to the matching

densitometry value of α-tubulin as the internal control. The change

in the expression levels of p-p38, p-JNK, p-ERK and p-STAT3 was

based on the expression levels of p38, JNK, ERK and STAT3.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

levels

MCF-7 cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates

(1×105 cells/per well) and incubated for 24 h, and then

treated with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, as

aforementioned. MCF-7 cells were pretreated with

N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for

30 min at 37°C and then treated with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 12

h at 37°C. ROS levels were estimated using a fluorescent probe

comprising 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The cells were harvested and

centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature and

incubated with DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. The

substrate solution was subsequently removed and the cells were

washed three times with PBS. Flow cytometric analysis was used to

determine the levels of ROS and CytExpert software (version 1.2;

Beckman Coulter, Inc.) was used to analyze the data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software (version 21.0; IBM Corp.). Data are expressed as the mean

± standard deviation. Multiple comparisons between groups were

performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

All experiments were replicated three times. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Quinalizarin inhibits the viability of

human breast cancer cells but not normal cells

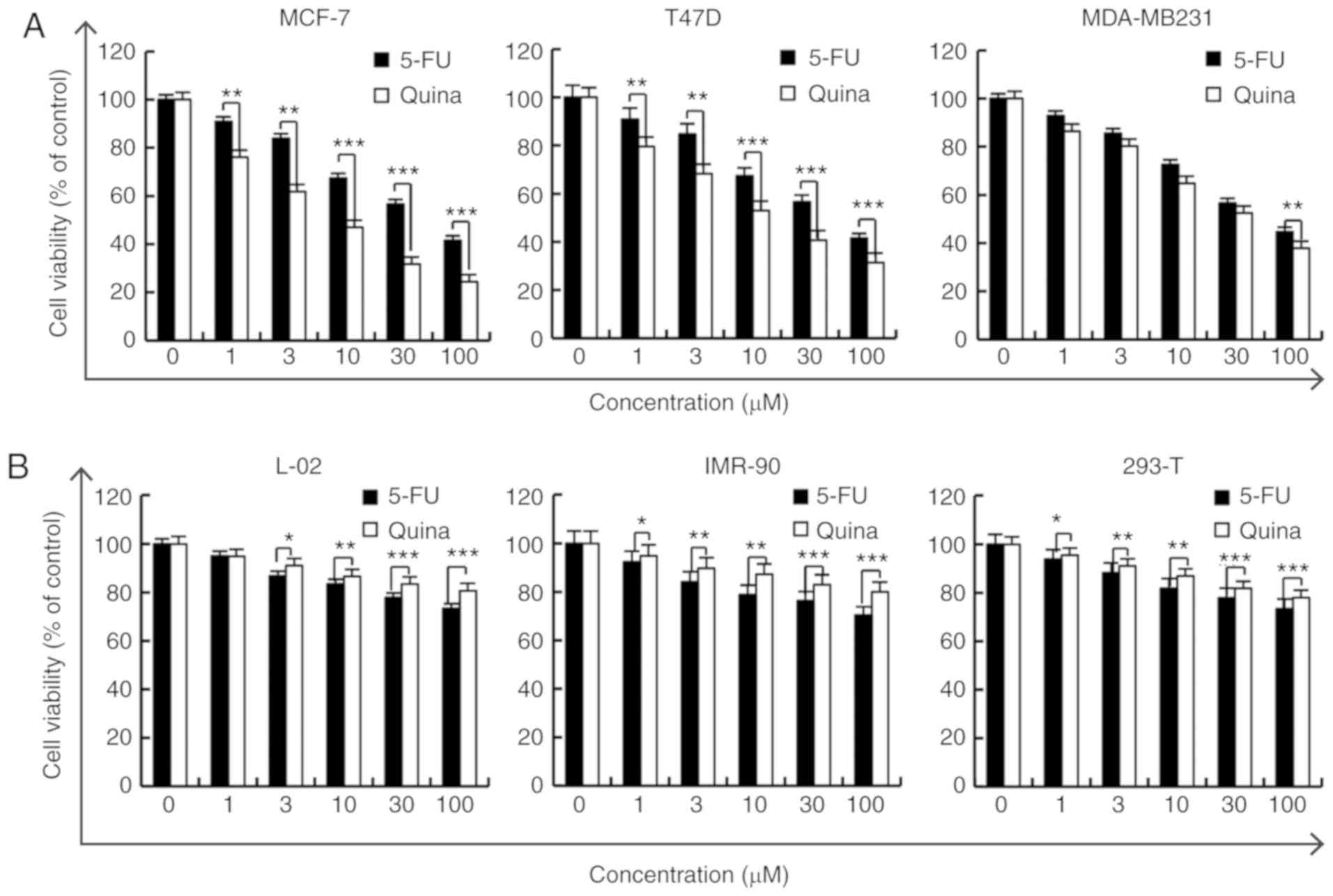

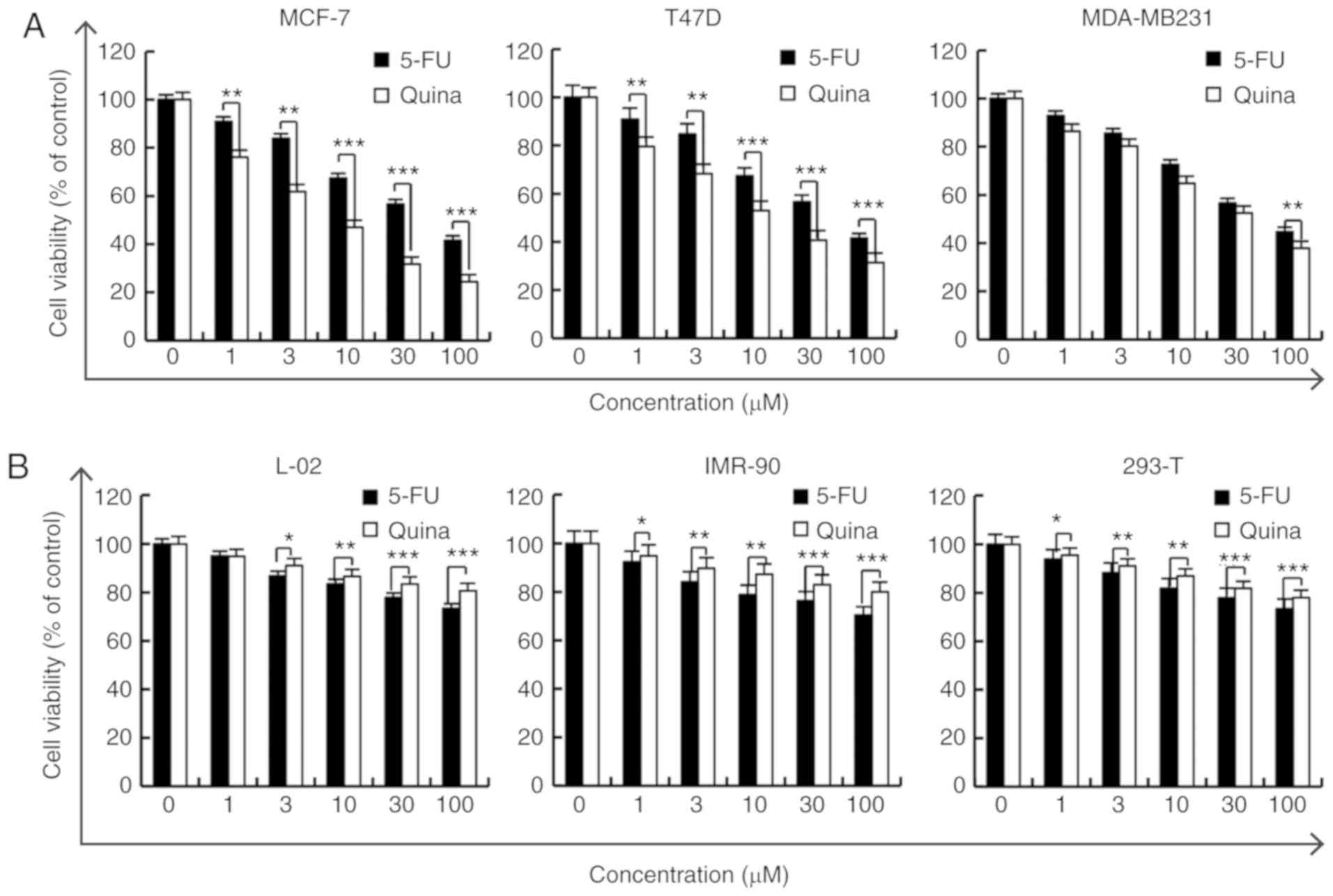

In order to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of

quinalizarin in human breast cancer cells, MCF-7, T47D and

MDA-MB231 cells were treated with different concentrations of

quinalizarin or 5-FU (1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 µmol/l) for 24 h, after

which the MTT assay was performed to measure cell viability.

Quinalizarin inhibited MDA-MB231 (estrogen-receptor-negative,

IC50 value 30.11 µmol/l) cell viability and

significantly inhibited the viability of the

estrogen-receptor-positive cell lines in a dose-dependent manner,

more so than 5-FU. The IC50 values for quinalizarin in

MCF-7 and T47D cells were 12.66 and 15.21 µmol/l, respectively

(Fig. 1A). Due to the MCF-7 cells

having the lowest IC50 value (12.66 µmol/l) and being

the most sensitive to quinalizarin, this cell line was selected as

the model system to investigate the effects of quinalizarin on

apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Furthermore, there were no

effective cytotoxic effects of quinalizarin when compared with the

5-FU-treated group in the L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T cell lines

(Fig. 1B). These results

demonstrated that quinalizarin had cytotoxic effects in MCF-7, T47D

and MDA-MB231 cell lines, but not in the L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T

cell lines, which may provide initial evidence that the

pro-apoptotic effects of quinazirilin are specific to

estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells.

| Figure 1.Quinalizarin inhibits the viability

of human breast cancer cells. (A) MCF-7, T47D and MDA-MB231 cells,

and (B) L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T cells, were treated with 1, 3, 10,

30 and 100 µmol/l 5-FU or quinalizarin for 24 h, and then cell

viability was measured via a MTT assay. The results are presented

as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, as indicated. 5-FU,

5-fluorouracil; Quina, quinalizarin. |

Quinalizarin induces apoptosis in

MCF-7 cells

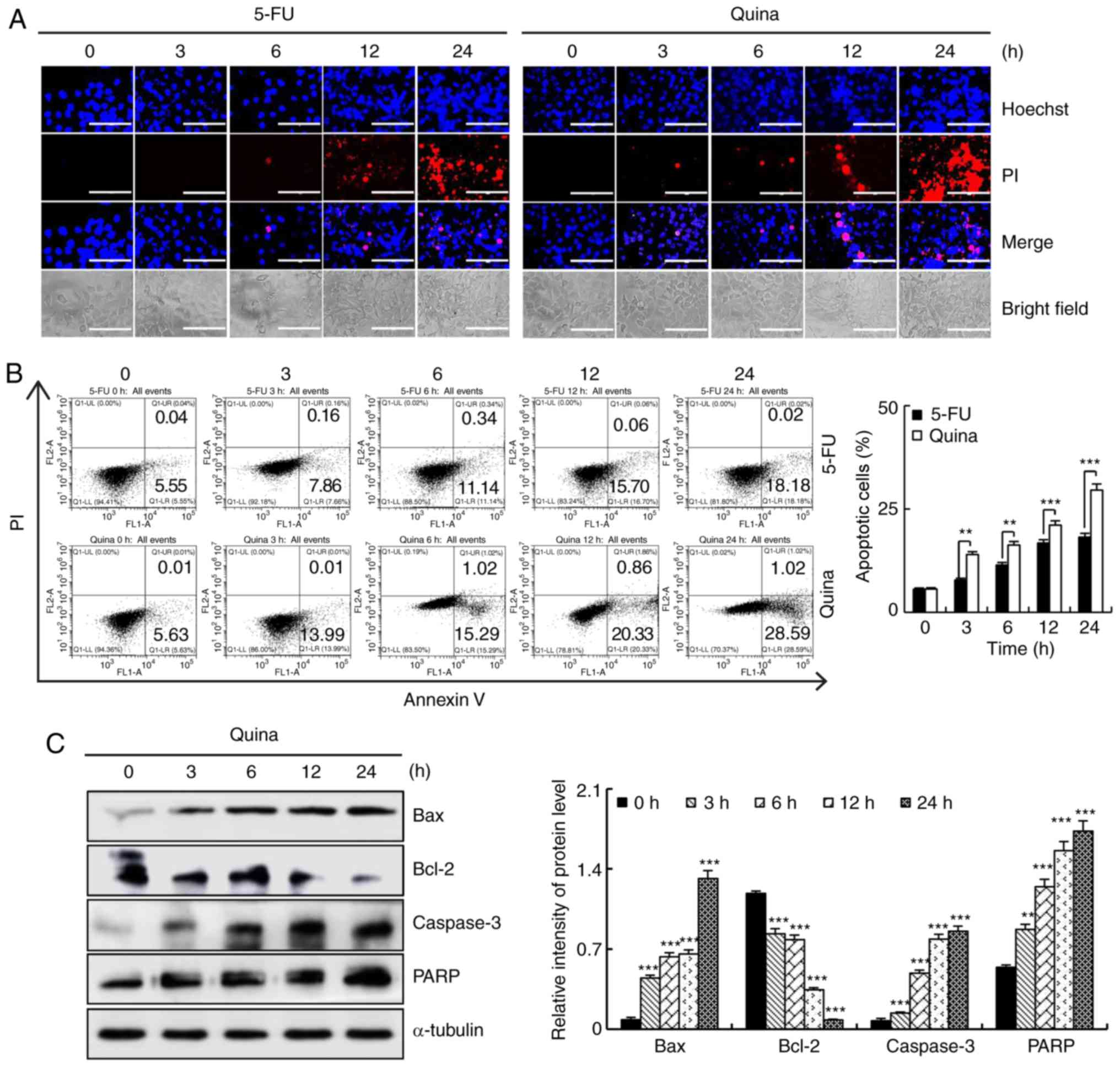

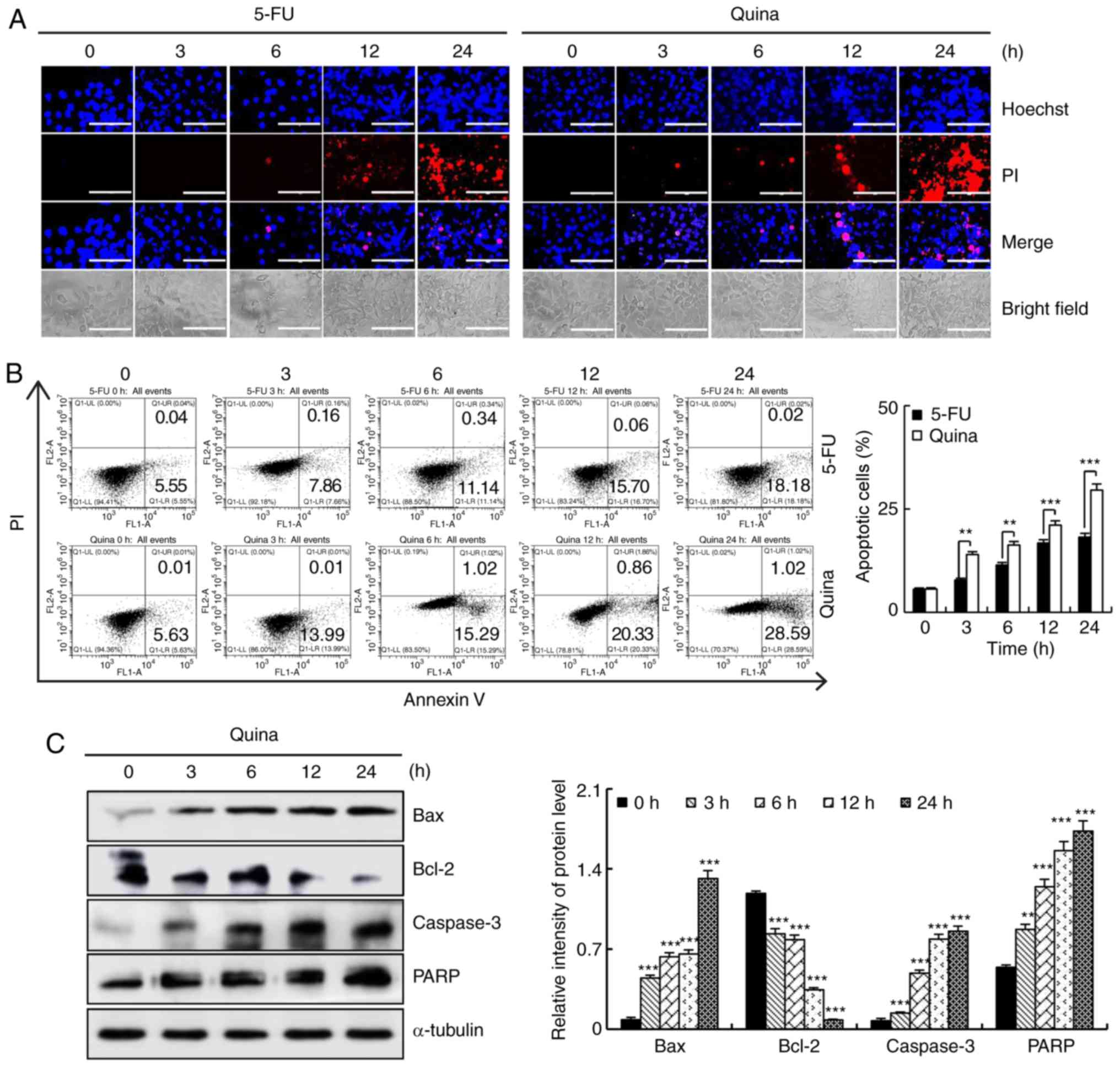

To determine whether quinalizarin induces apoptosis

in human breast cancer cells, MCF-7 cells were treated with 10

µmol/l quinalizarin or 10 µmol/l 5-FU for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h,

followed by Hoechst staining, flow cytometric analyses and western

blotting to measure cell apoptosis. As presented in Fig. 2A, MCF-7 cells treated with

quinalizarin for 24 h exhibited cell shrinkage and chromatin

condensation, as demonstrated by a strong bright red fluorescence.

The flow cytometric analysis results revealed that treatment with

quinalizarin for 24 h markedly increased the rate of apoptosis to

29.61%, and significantly increased cell apoptosis between 3 and 24

h compared with 5-FU (Fig. 2B). In

addition, quinalizarin also significantly increased the expression

levels of Bax, caspase-3 and PARP proteins in a time-dependent

manner, and decreased the expression levels of Bcl-2 protein

(Fig. 2C). These results suggested

that quinalizarin-induced apoptosis was partially mediated by the

mitochondrial pathway and caspase activation in MCF-7 cells.

| Figure 2.Quinalizarin induces apoptosis in

human breast cancer cells. (A) Cells were treated with 10 µmol/l

5-FU or 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, after which

the cell morphology and fluorescence intensity were observed by

fluorescence microscopy. Scale bars, 200 µm. (B) Cells were treated

with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, and apoptosis

was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis. **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001, as indicated. (C) The expression levels of Bax,

Bcl-2, caspase-3 and PARP in MCF-7 cells were analyzed via western

blotting. Error bars indicate the mean ± standard deviation of

three independent experiments. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0

h. 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; Quina, quinalizarin; PI, propidium iodide;

PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. |

Quinalizarin induces cell cycle arrest

in MCF-7 cells

To investigate whether quinalizarin induced cell

cycle arrest in human breast cancer cells, MCF-7 cells were treated

with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, followed by flow

cytometric analyses and western blotting to evaluate cell cycle

arrest. Quinalizarin significantly increased the number of cells in

the G2/M phase and decreased the number of cells in the

G0/G1 and S phases in a time-dependent manner

(Fig. 3A). The western blotting

results revealed that the expression levels of the G2/M

phase-associated proteins CDK1/2 and cyclin B1 were decreased, and

the expression levels of p21 and p27 were increased over time

(Fig. 3B). These results suggested

that quinalizarin caused G2/M phase cell cycle arrest

through alterations in p21, p27 and G2/M phase cell

cycle-associated protein expression in MCF-7 cells.

Quinalizarin induces apoptosis via

MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells

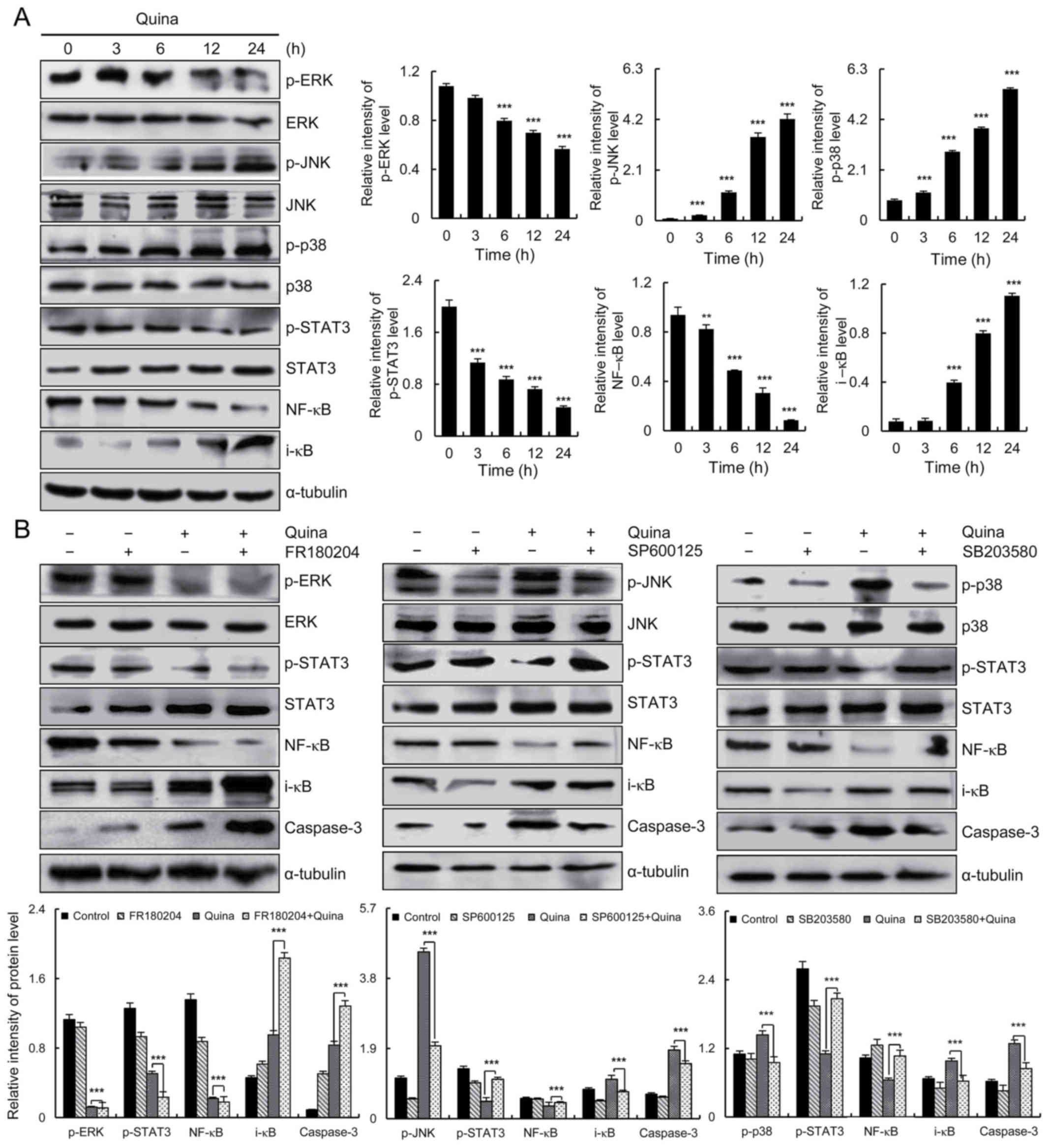

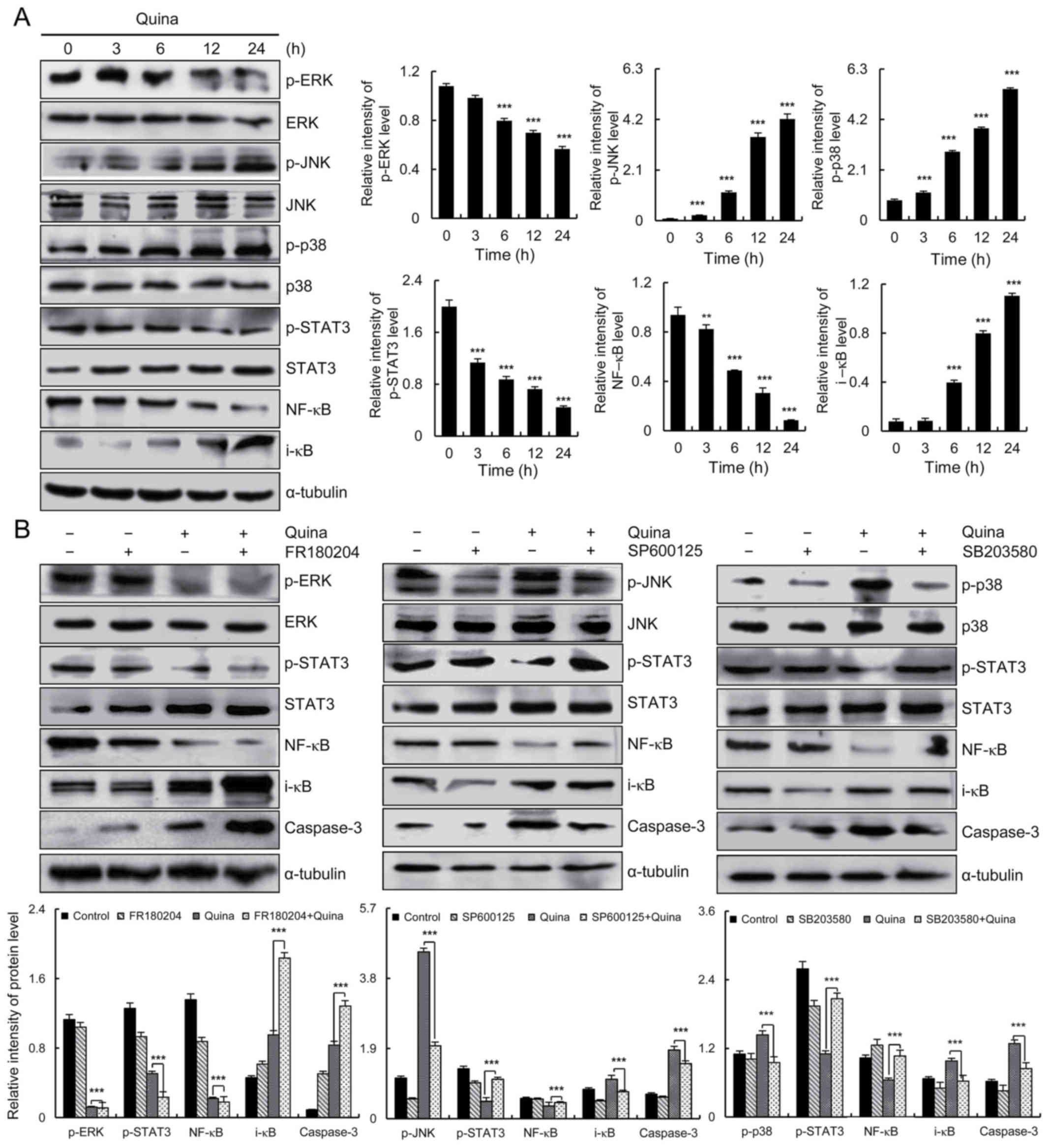

In order to determine whether quinalizarin-induced

MCF-7 cell apoptosis involved the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling

pathways, MCF-7 cells were treated with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin for

3, 6, 12 and 24 h, followed by western blotting to measure protein

expression levels. Quinalizarin suppressed the level of p-ERK,

p-STAT3 and NF-κB in a time-dependent manner, and increased the

levels of p-JNK, p-p38 and i-κB (Fig.

4A). In order to investigate whether the MAPK signaling pathway

is involved in the regulation of the STAT3 and NF-κB signaling

pathways, MCF-7 cells were treated with the p38 inhibitor

(SB203580), JNK inhibitor (SP600125) and ERK inhibitor (FR180204).

After 24 h, the decreased protein expression levels of p-STAT3 and

NF-κB induced by quinalizarin were blocked by the addition of the

p38 and JNK inhibitors. p-STAT3 and NF-κB protein expressions were

further suppressed following the addition of the ERK inhibitor and

quinalizarin, when compared with quinalizarin treatment alone

(Fig. 4B). These results

demonstrated that the MAPK signaling pathway can regulate the

expression levels of STAT3 and NF-κB, and quinalizarin induced

MCF-7 cell apoptosis via the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling

pathways.

| Figure 4.Quinalizarin induces cell apoptosis

in human breast cancer cells via the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB

signaling pathways. (A) Expression levels of ERK, JNK, p38, STAT3,

NF-κB, and i-κB proteins were analyzed via western blotting.

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 h. (B) Cells were pre-incubated

for 1 h with 12.1 µmol/l SB203580 and then treated with 10 µmol/l

quinalizarin. The expression levels of p38, STAT3, NF-κB, i-κB and

caspase-3 were analyzed via western blotting. The expression levels

of p-JNK, STAT3, NF-κB, i-κB and caspase-3 were analyzed via

western blotting. Cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with 12.1 µmol/l

FR180204 and then treated with 10 µmol/l quinalizarin. The

expression levels of p-ERK, STAT3, NF-κB, i-κB and caspase-3 were

analyzed via western blotting. Error bars indicate the mean ±

standard deviation of three independent experiments. ***P<0.001,

as indicated. MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; STAT3, signal

transducer and activator of transcription-3; ERK, extracellular

signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; p-,

phosphorylated; quina, quinalizarin. |

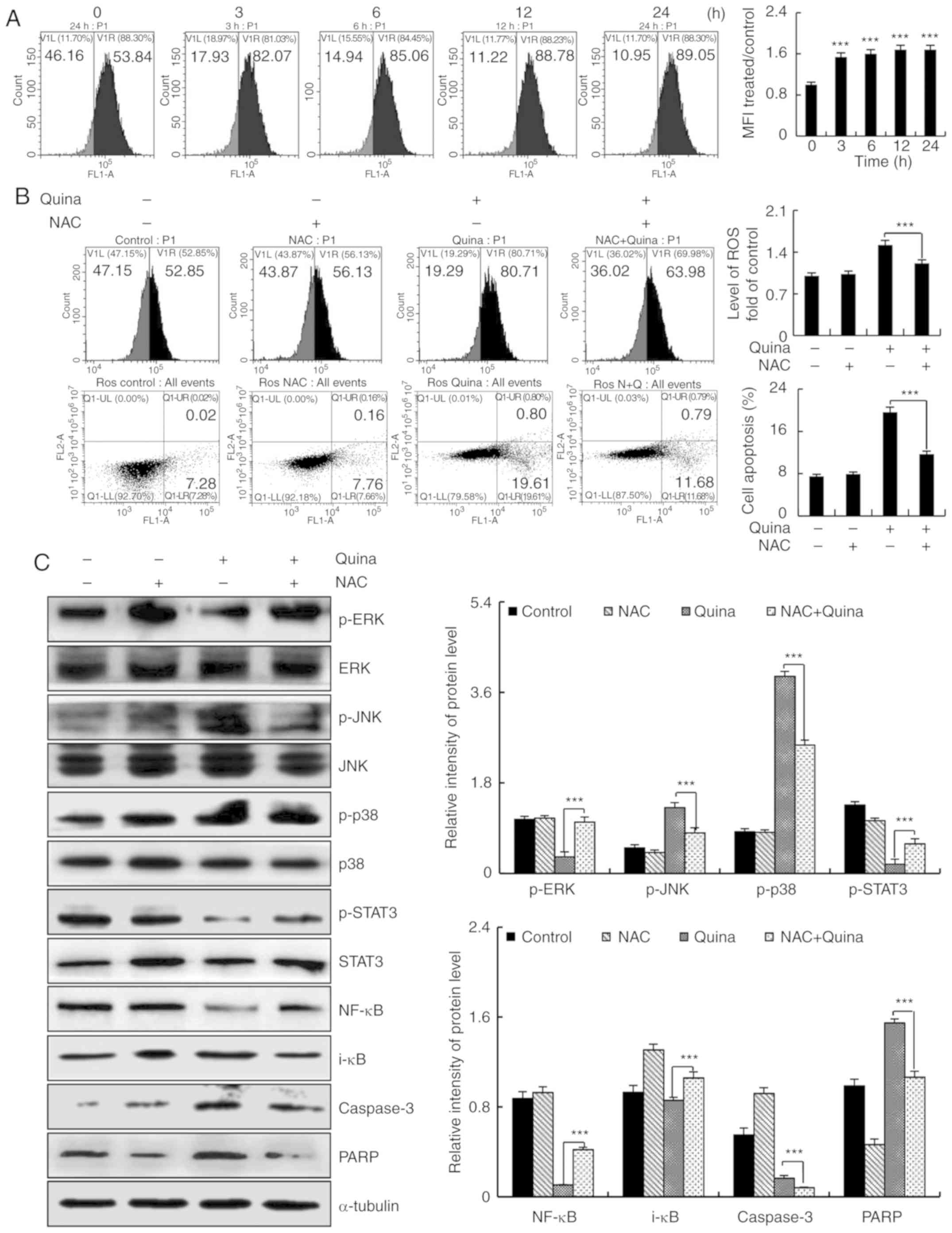

Quinalizarin induces apoptosis by

accelerating ROS generation in MCF-7 cells

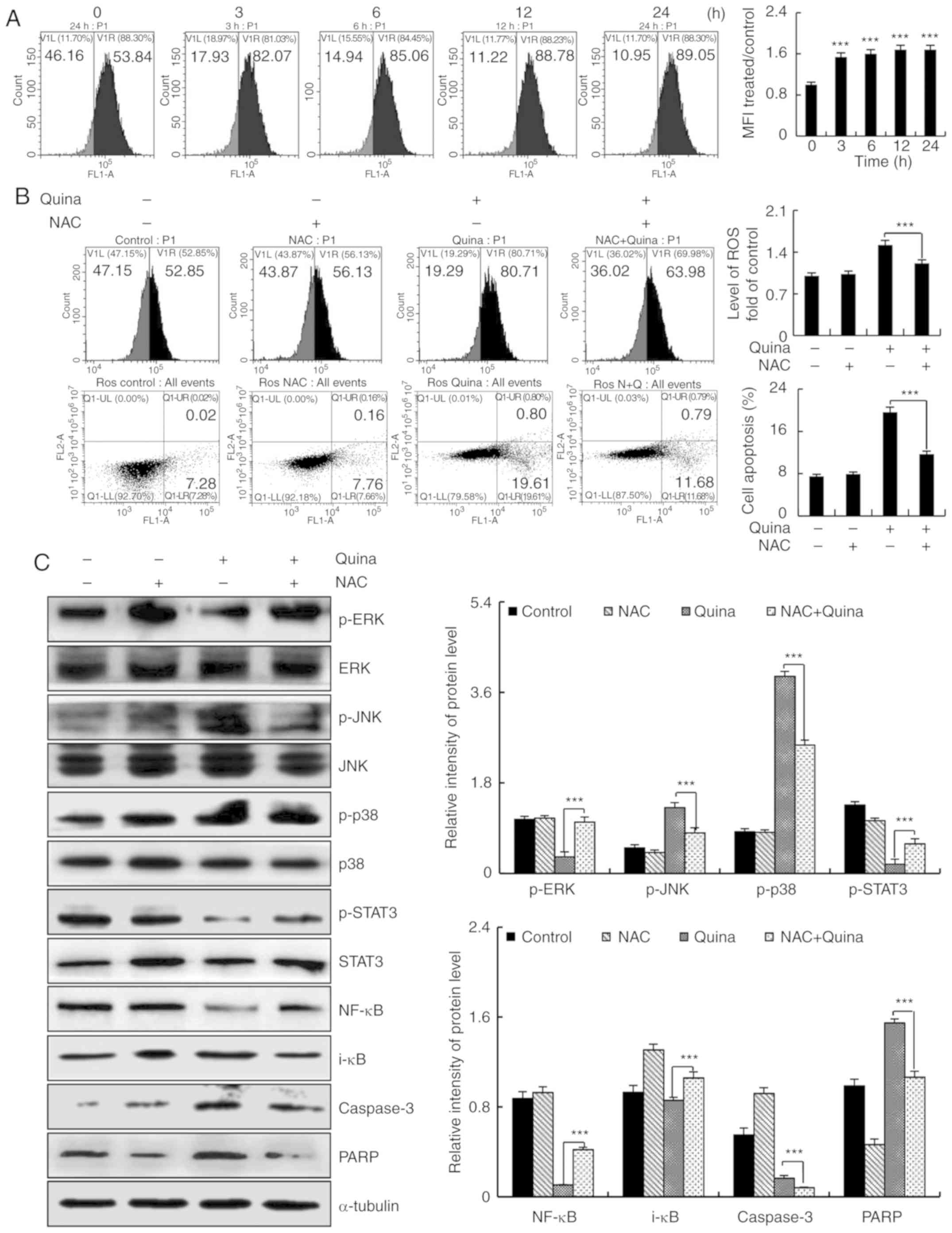

To determine whether quinalizarin-induced cell

apoptosis was preceded by ROS generation, MCF-7 cells were treated

with quinalizarin (10 µmol/l) for 24 h, followed by flow cytometric

analyses and western blotting to measure ROS levels. Quinalizarin

increased the levels of intracellular ROS accumulation in MCF-7

cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig.

5A), but pre-incubation with NAC for 24 h partially prevented

the quinalizarin-induced accumulation of ROS. Following

pretreatment with NAC, the quinalizarin-induced apoptosis was

reversed (Fig. 5B). NAC blocked

the quinalizarin-induced decrease in the expression levels of

p-ERK, p-STAT3 and NF-κB, and also blocked the quinalizarin-induced

increase in the expression levels of p-JNK, p-p38, i-κB, caspase-3

and PARP (Fig. 5C). These results

demonstrated that ROS generation is a major regulator of

quinalizarin-induced mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis and

G2/M cell cycle arrest through ROS-mediated MAPK, STAT3

and NF-κB signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6).

| Figure 5.Quinalizarin induces ROS-mediated

apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. (A) Cells were treated with

10 µmol/l quinalizarin for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, and the intracellular

ROS levels were analyzed via flow cytometric analyses.

***P<0.001 vs. 0 h. (B) Cells were treated with NAC or

quinalizarin for 24 h, the generation of ROS and cell apoptosis

were analyzed via flow cytometric analyses. ***P<0.001, as

indicated. (C) The expression levels of ERK, JNK, p38, STAT3,

NF-κB, i-κB, caspase-3 and PARP were analyzed via western blotting.

Error bars indicate the mean ± standard deviation of three

independent experiments. ***P<0.001, as indicated. ROS, reactive

oxygen species; NAC, N-acetyl-L-cysteine; ERK, ERK, extracellular

signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; STAT3,

signal transducer and activator of transcription-3; p-,

phosphorylated; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. |

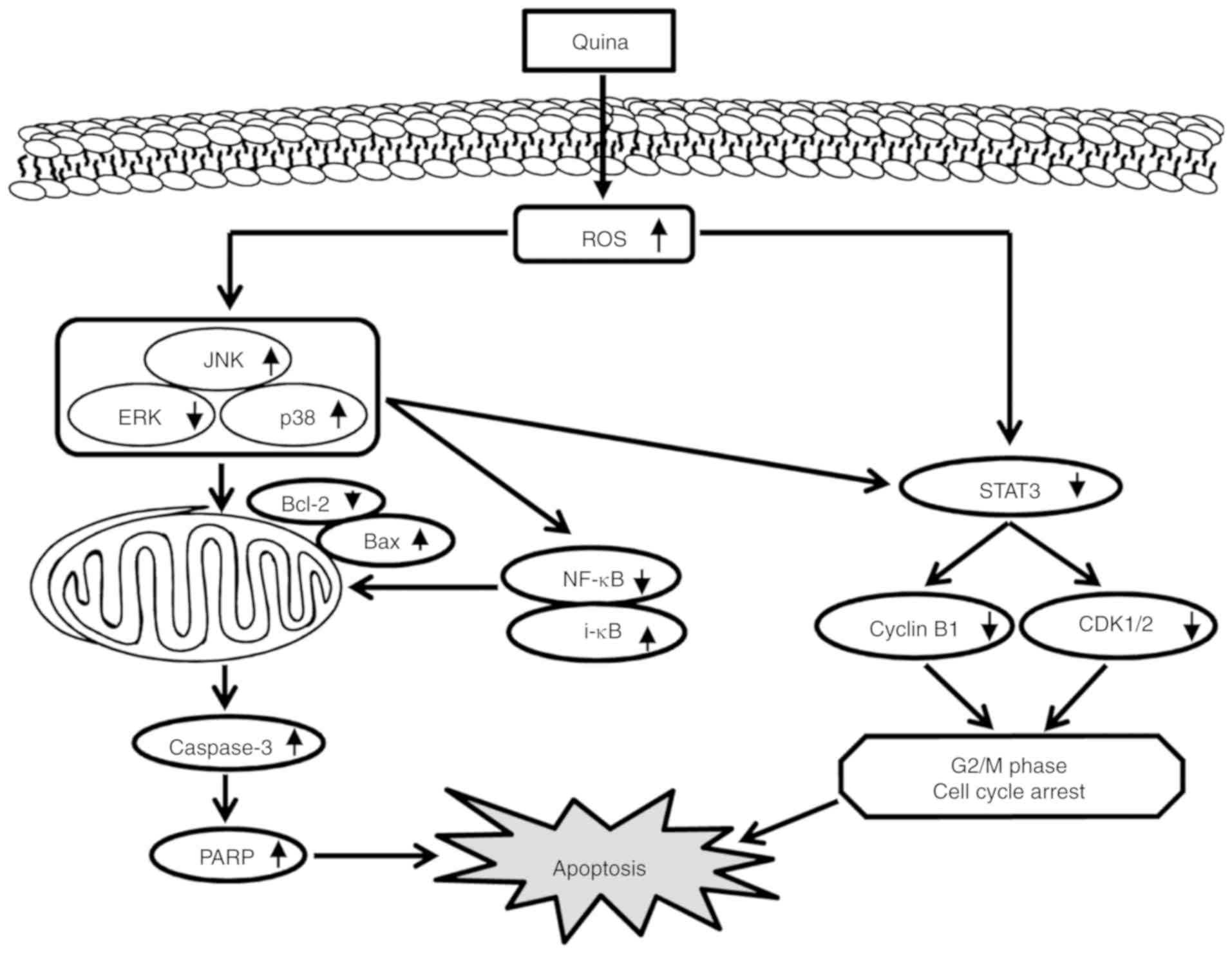

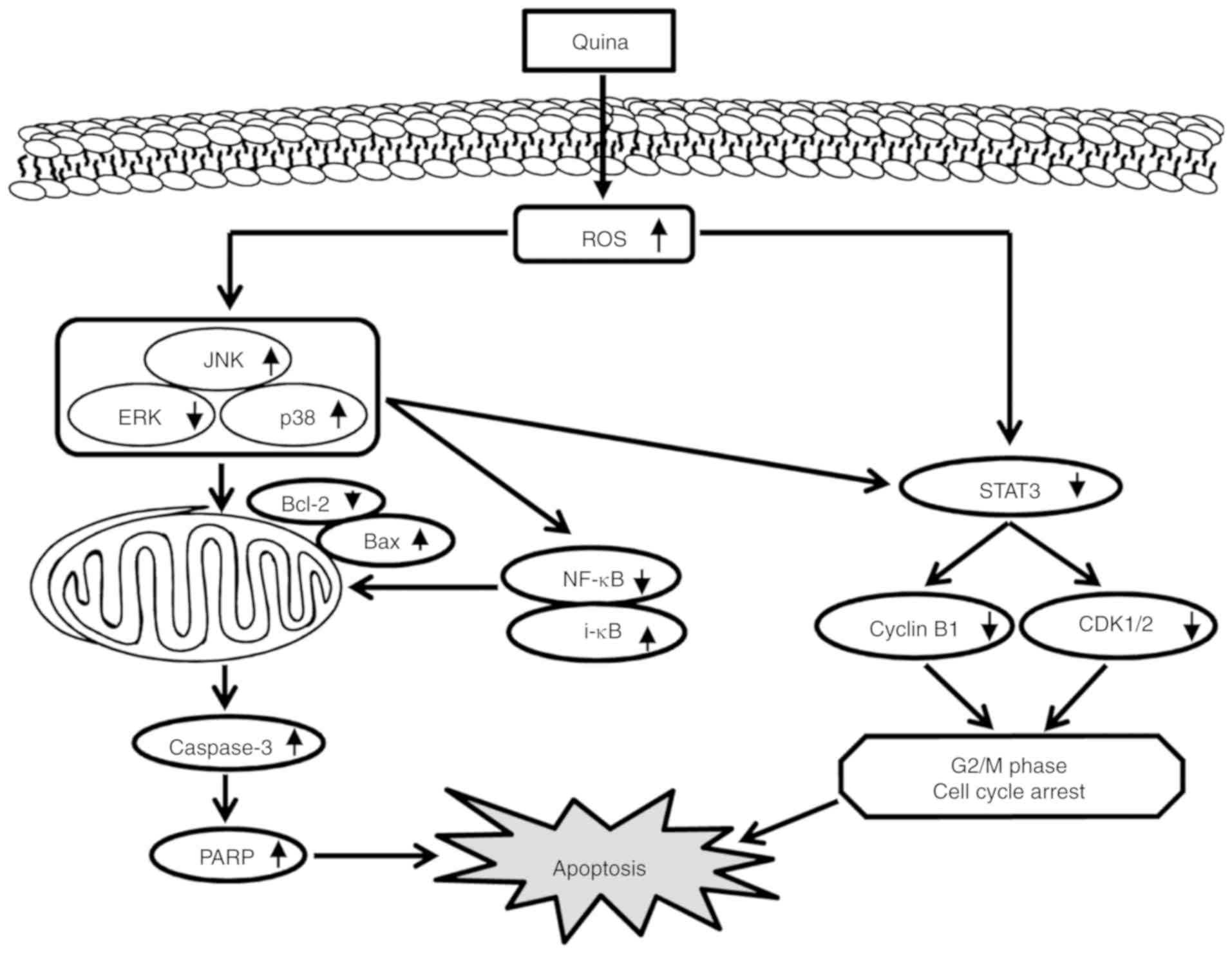

| Figure 6.Schematic diagram of the signaling

pathways in MCF-7 cells affected by quinalizarin. Quinalizarin

induced apoptosis in the human breast cancer cells. The anticancer

effects of quinalizarin induced ROS-mediated mitochondrial

apoptosis by the MAPK, STAT3, and NF-κB signaling pathways. ROS,

reactive oxygen species; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase;

STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription-3; quina,

quinalizarin; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; ERK, ERK, extracellular

signal-regulated kinase; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. |

Discussion

Anthraquinone compounds, an important class of

natural and synthetic compounds, include emodin, rhein,

aloe-emodin, apigenin and quinalizarin (23). Numerous studies have reported that

rhein, apigenin, aloe-emodin and emodin affect the cell

proliferation, migration and apoptosis of different pathological

and genetic types of human cancer cell lines (24,25).

In addition, studies have also reported that anthraquinone

derivatives possess a number of identical activities as they have

an identical mother nucleus (26,27).

Similarly, the present study demonstrated that quinalizarin, an

anthraquinone compound, significantly inhibited MCF-7

(IC50, 12.66 µmol/l) and T47D (IC50 15.21

µmol/l) cell viability as determined by the MTT assay, and had less

toxicity in L-02, IMR-90 and 293-T cells. Thus, quinalizarin may

possess effective anti-tumor activities and decrease cytotoxicity

in normal human cells compared with 5-FU. In order to confirm this

theory, the present study investigated the anti-tumor mechanisms of

quinalizarin in human breast cancer cell lines.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is a

critical defense mechanism in inhibiting the development of cancer

(28). The mitochondrial pathway

is one form of apoptosis signaling pathway. Bax and Bcl-2 are Bcl-2

family members that are fundamental for the balance between cell

survival and death in the mitochondrial pathway (29). In the mitochondrial pathway,

caspase-3 is primarily responsible for PARP activation during cell

apoptosis (30). A recent study

demonstrated that emodin, an anthraquinone, decreased the

expression levels of Bcl-2; increased the levels of caspase-3, PARP

and Bax; and induced apoptosis by modulating the expression of

apoptosis-associated genes in human breast cancer cells (31). Similarly, the results from the

present study revealed that quinalizarin significantly induced the

apoptosis of MCF-7 cells by promoting the expression levels of Bax,

downregulating Bcl-2 and activating caspase-3 and PARP. These

findings suggested that quinalizarin induced apoptosis via the

mitochondrial pathway in the human breast cancer cell line,

MCF-7.

In addition to the activation of the mitochondrial

pathway checkpoint, cell cycle control is another primary

regulatory mechanism that controls cell growth and induces cell

apoptosis (32). In eukaryotic

cells, CDK1/2 and cyclin B1 proteins control entry into mitosis

(G2/M) and are involved in regulatory and structural

processes required for mitosis, such as formation of the spindle

and attachment of chromosomes to the spindle. However, these

CDK/cyclin complexes are negatively regulated by p21 and p27. Thus,

tumor-associated G2/M phase arrest is often mediated by

alterations in cyclin B1/CDK complex protein activity and the

expression levels of p21 and p27 (33–36).

Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that the MAPK and

STAT3 signaling pathways regulate the eukaryotic cell cycle

(37–38). Aloe-emodin, a type of

anthraquinone, induces cell death through S-phase arrest and

caspase-dependent pathways in human tongue squamous cancer SCC-4

cells, which involves ROS generation (39). The results from the present study

coincide with evidence suggesting that quinalizarin causes

G2/M phase arrest, as the expression levels of p21 and

p27 were significantly increased, and the cyclin B1 and CDK1/2

complex protein, which is required for progression through the

G2 and M phases, were inhibited. These results suggested

that quinalizarin-mediated inhibition of MCF-7 cell proliferation

may involve G2/M phase arrest and expression of

G2/M phase-associated proteins.

The present study also focused on numerous crucial

protein kinases that play roles in regulating the cell cycle and

apoptosis, including JNK, p38, ERK, STAT3 and NF-κB. JNK and p38

induce apoptosis, while ERK promotes cell survival (40–42).

Rhein, a type of anthraquinone, induced apoptosis in human and rat

glioma cells by blocking ERK kinase activity (43). The activation of and interactions

between STAT3 and NF-κB have been demonstrated in a number of

different types of cancer, such as colon, gastric and liver cancer

(44). Apigenin, another type of

anthraquinone, induces apoptosis by decreasing the expression

levels of p-STAT3 and blocking the activation of the STAT3 and

NF-κB signaling pathway in MCF-7 cells (45). The results from the present study

demonstrated that quinalizarin could upregulate the expression

levels of p-p38, p-JNK and i-κB, and inhibit p-ERK, p-STAT3 and

NF-κB activity. The association between the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB

signaling pathways were also investigated by inhibiting p-JNK,

p-p38 and p-ERK activation. It was important to note that the

protein levels of p-STAT3 and NF-κB increased, and caspase-3 and

i-κB decreased following treatment with JNK or p38 inhibitors.

Inhibition of ERK activation further decreased the protein levels

of p-STAT3 and NF-κB, and caspase-3 and i-κB levels increased in

MCF-7 cells. These data demonstrate that p-STAT3 and NF-κB were

decreased in quinalizarin-treated cells and were regulated by MAPK

signaling. Therefore, MAPK is considered to be an important factor

for the quinalizarin-mediated induction of apoptosis in MCF-7

cells. These results also demonstrated that quinalizarin-induced

apoptosis was mediated through the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling

pathways. In addition, it has been reported that copper chelating

peptide-anthraquinones have the redox effects of a quinone ring to

generate free radical species capable of damaging DNA (46). Quinone-containing drugs undergo a

one-electron reduction to the corresponding semiquinone radicals

which, in the presence of molecular oxygen, produces a superoxide

anion radical, hydrogen peroxide (47). The quinone ring structures of

copper chelating peptide-anthraquinones are similar to that of

quinalizarin (46,48). Thus, it was hypothesized that

quinalizarin caused cell oxidative stress, and induced MCF-7 cell

apoptosis by regulating the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling

pathways.

ROS, which serve as redox messengers, are usually

maintained at tolerable levels under normal physiological

conditions, but high ROS levels elicit oxidative stress, leading to

cell death via apoptosis (49–52).

The overproduction of intracellular ROS has been associated with

the apoptotic response induced by several anticancer agents

(53), and excessive ROS

accumulation promotes cell apoptosis through various mechanisms,

including prolonged MAPK activation and inhibition of p-STAT3 and

NF-κB (54,55). A recent study revealed

emodin-induced apoptosis of colon cancer cells in a ROS-dependent

manner (56). It has been reported

that emodin-mediated ROS production acts as an early and upstream

change in the cell death cascade to antagonize cytoprotective ERK

and AKT signaling, Bcl-2 and Bax modulation, and caspase

activation, consequently leading to apoptosis in A549 cells

(57). The results from the

present study coincide with the aforementioned studies. DCFH-DA

staining, one of the most straightforward techniques for directly

measuring the redox state of cells (58), demonstrated that

quinalizarin-induced apoptosis was accompanied by ROS accumulation.

In order to determine the association between quinalizarin-induced

apoptosis and ROS, the NAC antioxidant was used to pretreat MCF-7

cells in the present study. The results revealed that quinalizarin

did not directly regulate the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling

pathways, but rather induced their indirect regulation by

stimulating ROS accumulation, thereby promoting apoptosis in MCF-7

cells.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

quinalizarin induced ROS generation and subsequently inhibited the

activation of the MAPK, STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways, which

increased G2/M cell cycle arrest and caspase-dependent

apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. These data are indicative

of the value of further studies regarding the application of

quinalizarin as a potential treatment for breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Multigrain

Production and Processing Characteristic Discipline Construction

Project (grant no. 2042070010), the Postdoctoral Scientific

Research Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (grant no.

LBH-Q13132) and the Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University

Support Program for ‘San Zong’ (grant no. TDJH201805).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the present

study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

CHJ and CQY conceived and designed the study. YaQZ,

YYF, YHL, YuQZ, XYJ, YCF, YNS and JRW performed the experiments.

YaQZ, YYF and YHL analyzed the data. YaQZ and YYF wrote the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Elzawawy A: Breast cancer systemic

therapy: The need for more economically sustainable scientific

strategies in the world. Breast Care (Base). 3:434–438. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Mccarron P and Parkin DM: The

changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and

mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 6:229–239. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Van Agthoven T, Sieuwerts AM, Meijer D,

Meijer-van Gelder ME, van Agthoven TL, Sarwari R, Sleijfer S,

Foekens JA and Dorssers LC: Selective recruitment of breast cancer

anti-estrogen resistance genes and relevance for breast cancer

progression and tamoxifen therapy response. Endocr Relat Cancer.

17:215–230. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Feiten S, Dünnebacke J, Heymanns J,

Köppler H, Thomalla J, Van Roye C, Wey D and Weide R: Breast cancer

morbidity: Questionnaire survey of patients on the long term

effects of disease and adjuvant therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int.

111:537–544. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S,

Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, Rodrigues A, Fodor M, Chao Y, Voznyi

E, et al: Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus

fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line

therapy for advanced gastric cancer: A report of the V325 study

group. J Clin Oncol. 24:4991–4997. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fesik SW: Promoting apoptosis as a

strategy for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 5:876–885.

2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yu I and Cheung WY: Comparison of 5-FU

versus capecitabine in combination with mitomycin or cisplatin in

the treatment of anal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 35:680. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Haagenson KK and Wu GS: Mitogen activated

protein kinase phosphatases and cancer. Cancer Biol Ther.

9:337–340. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shao Y and Aplin AE: ERK2 phosphorylation

of serine 77 regulates Bmf pro-apoptotic activity. Cell Death Dis.

3:e2532012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Inoue J, Gohda J, Akiyama T and Semba K:

NF-kappaB activation in development and progression of cancer.

Cancer Sci. 98:268–274. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tang X, Soch E, Shishodia S, Diane LJ,

Jack L, Waun KH, Bharat A and Ignacio IW: Immunohistochemical

analysis indicates that nuclear factor-κB (NF-alysis frequently

activated in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 46:1–5. 2005.

|

|

12

|

Grivennikov SI and Karin M: Dangerous

liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in

cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21:11–19. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang J, Wang X, Vikash V, Ye Q, Wu D, Liu

Y and Dong W: ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2016:43509652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jacquemin G, Margiotta D, Kasahara A,

Bassoy EY, Walch M, Thiery J, Lieberman J and Martinvalet D:

Granzyme B-induced mitochondrial ROS are required for apoptosis.

Cell Death Differ. 22:862–874. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Redzadutordoir M and Averillbates DA:

Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen

species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1863:2977–2992. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wen L, Lu X, Wang R, Jin X, Hu L and You

C: Pyrroloquinoline quinone induces chondrosarcoma cell apoptosis

by increasing intracellular reactive oxygen species. Mol Med Rep.

17:7184–7190. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bu HQ, Cai K, Shen F, Bao XD, Xu Y, Yu F,

Pan HQ, Chen CH, Du ZJ and Cui JH: Induction of apoptosis by

capsaicin in hepatocellular cancer cell line SMMC-7721 is mediated

through ROS generation and activation of JNK and p38 MAPK pathways.

Neoplasma. 62:582–591. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Vogel J, Bumgarner J, Espinosa N and Young

W: An evaluation of the use of resistivity counters in the touchet

river in washington and the imnaha river in oregon. Am Fish Soc.

33:6953–6960. 2011.

|

|

19

|

Piska K, Koczurkiewicz P, Bucki A,

Wójcik-Pszczoła K, Kołaczkowski M and Pękala E: Metabolic carbonyl

reduction of anthracyclines-role in cardiotoxicity and cancer

resistance. Reducing enzymes as putative targets for novel

cardioprotective and chemosensitizing agents. Invest New Drugs.

35:375–385. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cozza G, Venerando A, Sarno S and Pinna

LA: The selectivity of CK2 inhibitor quinalizarin: A reevaluation.

Biomed Res Int. 2015:1–9. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Meng LQ, Liu C, Luo YH, Piao XJ, Wang Y,

Zhang Y, Wang JR, Wang H, Xu WT, Liu Y, et al: Quinalizarin exerts

an anti-tumour effect on lung cancer A549 cells by modulating the

Akt, MAPK, STAT3 and p53 signaling pathways. Mol Med Rep.

17:2626–2634. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhou Y, Li K, Zhang S, Li Q, Li Z, Zhou F,

Dong X, Liu L, Wu G and Meng R: Quinalizarin, a specific CK2

inhibitor, reduces cell viability and suppresses migration and

accelerates apoptosis in different human lung cancer cell lines.

Indian J Cancer. 52 (Suppl 2):e119–e124. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Malik EM and Müller CE: Anthraquinones as

pharmacological tools and drugs. Med Res Rev. 36:705–748. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lordan S, O'Neill C and O'Brien NM:

Effects of apigenin, lycopene and astaxanthin on 7

beta-hydroxycholesterol-induced apoptosis and Akt phosphorylation

in U937 cells. Br J Nutr. 100:287–296. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen YY, Chiang SY, Lin JG, Ma YS, Liao

CL, Weng SW, Lai TY and Chung JG: Emodin, aloe-emodin and rhein

inhibit migration and invasion in human tongue cancer SCC-4 cells

through the inhibition of gene expression of matrix

metalloproteinase-9. Int J Oncol. 36:1113–1120. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang YY, Li ZC, Zhu JK, Yang ZY, Wang QJ,

He PG, Hang YZ, Pin JW, Yu GH and Fang Z: Simultaneous

determination of flavonoids and anthraquinones in chrysanthemum by

capillary electrophoresis with amperometry detection. Chin Chem

Lett. 21:1231–1234. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zong JR, Chao ZM, Liu ZL and Wang J:

Review about structure-function relationships of anthraquinone

derivatives from Radix et Rhizoma Rhei. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi.

33:2424–2427. 2008.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Martin KR: Using nutrigenomics to evaluate

apoptosis as a preemptive target in cancer prevention. Curr Cancer

Drug Targets. 7:438–446. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zheng JH, Viacava Follis A, Kriwacki RW

and Moldoveanu T: Discoveries and controversies in BCL-2

proteins-mediated apoptosis. FEBS J. 283:2690–2700. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Alenzi FQ, Lotfy M and Wyse R: Swords of

cell death: Caspase activation and regulation. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 11:271–280. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zu C, Zhang M, Xue H, Cai X, Zhao L, He A,

Qin G, Yang C and Zheng X: Emodin induces apoptosis of human breast

cancer cells by modulating the expression of apoptosis-related

genes. Oncol Lett. 10:2919–2924. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Antonsson A and Persson JL: Induction of

apoptosis by staurosporine involves the inhibition of expression of

the major cell cycle proteins at the G(2)/m checkpoint accompanied

by alterations in Erk and Akt kinase activities. Anticancer Res.

29:2893–2898. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gao SY, Li J, Qu XY, Zhu N and Ji YB:

Downregulation of Cdk1 and cyclinB1 expression contributes to

oridonin-induced cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase and growth

inhibition in SGC-7901 gastric cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 15:6437–6441. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nasheuer HP, Smith R, Bauerschmidt C,

Grosse F and Weisshart K: Initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication:

Regulation and mechanisms. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol.

72:41–70. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Santamaria D and Ortega S: Cyclins and

CDKS in development and cancer: Lessons from genetically modified

mice. Front Biosci. 11:1164–1188. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang Z, Leonard SS, Huang C, Castranova V

and Shi X: Role of reactive oxygen species and MAPKs in

vanadate-induced G(2)/M phase arrest. Free Radic Biol Med.

34:1333–1342. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wang XH, Liu BR, Qu B, Xing H, Gao SL, Yin

JM, Wang XF and Cheng YQ: Silencing STAT3 may inhibit cell growth

through regulating signaling pathway, telomerase, cell cycle,

apoptosis and angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Potential

uses for gene therapy. Neoplasma. 58:158–171. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Clotet J, Vendrell J and Escoté X: Control

of the cell cycle progression by the MAPK Hog1. MAP Kinase.

2:e32013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chiu TH, Lai WW, Hsia TC, Yang JS, Lai TY,

Wu PP, Ma CY, Yeh CC, Ho CC, Lu HF, et al: Aloe-emodin induces cell

death through S-phase arrest and caspase-dependent pathways in

human tongue squamous cancer SCC-4 cells. Anticancer Res.

29:4503–4511. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Su Y, Li G, Zhang X, Gu J, Zhang C, Tian Z

and Zhang J: JSI-124 inhibits glioblastoma multiforme cell

proliferation through G(2)/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis

augment. Cancer Biol Ther. 7:1243–1249. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Guo Y, Lin D, Zhang M, Zhang X, Li Y, Yang

R, Lu Y, Jin X, Yang M, Wang M, et al: CLDN6-induced apoptosis via

regulating ASK1-p38/JNK signaling in breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Int

J Oncol. 48:2435–2444. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cook SJ, Stuart K, Gilley R and Sale MJ:

Control of cell death and mitochondrial fission by ERK1/2 MAP

Kinase signaling. FEBS J. 284:4177–4195. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tang N, Chang J, Lu HC, Zhuang Z, Cheng

HL, Shi JX and Rao J: Rhein induces apoptosis and autophagy in

human and rat glioma cells and mediates cell differentiation by ERK

inhibition. Microb Pathog. 113:168–175. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Degoricija M, Situm M, Korać J, Miljković

A, Matić K, Paradžik M, Marinović Terzić I, Jerončić A, Tomić S and

Terzić J: High NF-κB and STAT3 activity in human urothelial

carcinoma: A pilot study. World J Urol. 32:1469–1475. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Seo HS, Choi HS, Kim SR, Choi YK, Woo SM,

Shin I, Woo JK, Park SY, Shin YC and Ko SG: Apigenin induces

apoptosis via extrinsic pathway, inducing p53 and inhibiting STAT3

and NFκB signaling in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Mol

Cell Biochem. 366:319–334. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Morier-Teissier E: Effect of a

copper-chelating peptide on the anticancer activity of

anthraquinones. J Pharm Belg. 45:347–354. 1990.(In French).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Morier-Teissier E, Bernier JL, Lohez M,

Catteau JP and Hénichart JP: Free radical production and DNA

cleavage by copper chelating peptide-anthraquinones. Anticancer

Drug Des. 5:291–305. 1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Cozza G, Mazzorana M, Papinutto E, Bain J,

Elliott M, di Maira G, Gianoncelli A, Pagano MA, Sarno S, Ruzzene

M, et al: Quinalizarin as a potent, selective and cell-permeable

inhibitor of protein kinase CK2. Biochem J. 421:387–395. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Prosperini A, Juan-García A, Font G and

Ruiz MJ: Beauvericin-induced cytotoxicity via, ROS production and

mitochondrial damage in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol Lett. 222:204–211.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Conway GE, Casey A, Milosavljevic V, Liu

Y, Howe O, Cullen PJ and Curtin JF: Non-thermal atmospheric plasma

induces ROS-independent cell death in U373MG glioma cells and

augments the cytotoxicity of temozolomide. Br J Cancer.

114:435–443. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Wang CH, Wu SB, Wu YT and Wei YH:

Oxidative stress response elicited by mitochondrial dysfunction:

Implication in the pathophysiology of aging. Exp Biol Med

(Maywood). 238:450–460. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Loor G, Kondapalli J, Schriewer JM,

Chandel NS, Vanden Hoek TL and Schumacker PT: Menadione triggers

cell death through ROS-dependent mechanisms involving PARP

activation without requiring apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med.

49:1925–1936. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lo YL and Wang W: Formononetin potentiates

epirubicin-induced apoptosis via ROS production in HeLa cells in

vitro. Chem Biol Interact. 205:188–197. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kim KY, Park KI, Kim SH, Yu SN, Lee D, Kim

YW, Noh KT, Ma JY, Seo YK and Ahn SC: Salinomycin induces reactive

oxygen species and apoptosis in aggressive breast cancer cells as

mediated with regulation of autophagy. Anticancer Res.

37:1747–1758. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

He G and Karin M: NF-κB and STAT3-key

players in liver inflammation and cancer. Cell Res. 21:159–168.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang Y, Luo Q, He X, Wei H, Wang T, Shao J

and Jiang X: Emodin induces apoptosis of colon cancer cells via

induction of autophagy in a ROS-Dependent manner. Oncol Res.

26:889–899. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Su YT, Chang HL, Shyue SK and Hsu SL:

Emodin induces apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma cells through

a reactive oxygen species-dependent mitochondrial signaling

pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 70:229–241. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Eruslanov E and Kusmartsev S:

Identification of ROS using oxidized DCFDA and flow-cytometry.

Methods Mol Biol. 594:57–72. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|