Introduction

Doxorubicin (DOX) is highly effective treatment

against acute lymphoblastic and myeloblastic leukemia, and numerous

types of solid tumors, including breast cancer, sarcomas and

childhood solid tumors (1).

However, clinical use of DOX is hampered by its potential

cardiotoxicity (1–5). Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

may attenuate DOX-induced cardiomyopathy (6–9);

however, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood and

there are very few studies examining the effects of simultaneous

treatment with DOX and ARBs for the prevention of DOX-induced

myocardial injury. Valsartan (Val), which is a type of ARB, is

widely used to treat patients with hypertension and heart failure

(10). A clinical observational

study demonstrated that Val could prevent the acute cardiotoxicity

induced by cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and

prednisolone, which are standard chemotherapeutic options for

treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (11). More recently, Sakr et al

(12) investigated the effect of

Val on DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in rats, and found that

concurrent or post-but not pre-treatment with Val attenuated

DOX-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress,

apoptosis and senescence. Another study reported that Val

alleviated DOX-induced cardiac dysfunction via regulation of the

TGF-β signaling pathway (13).

Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

is a known risk factor responsible for the initiation and

development of heart failure (14,15)

and DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. NAD(P)H oxidase (NOX) is one of

several contributing sources responsible for increased ROS

generation (16). NOX may be

activated by growth factors or inflammatory cytokines (17–19).

Previous studies confirmed that angiotensin II may stimulate ROS

production by activating NOX (20–23).

Therefore, it may be hypothesized that reduced NOX and ROS

signaling is involved in the beneficial effects of ARB on

attenuating DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

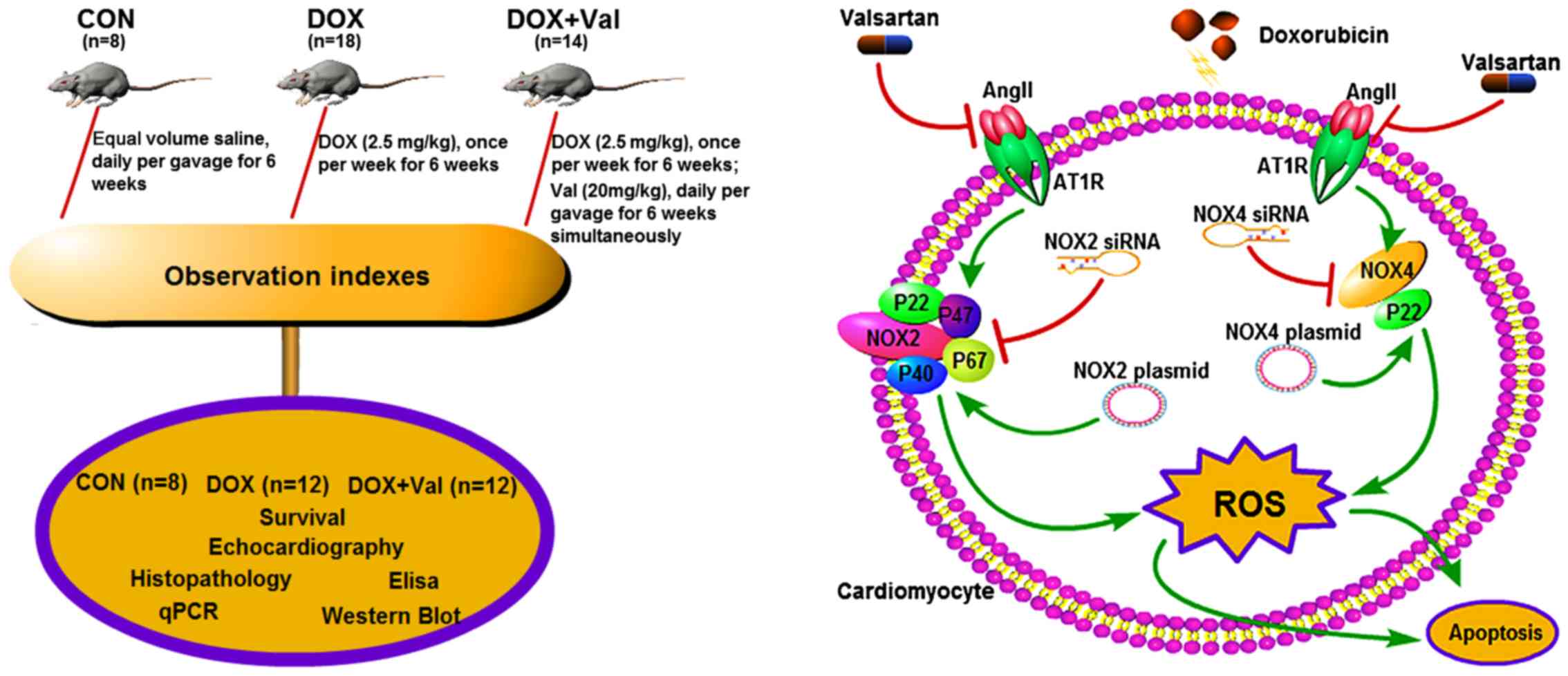

The aim of the present study was to test the

hypothesis that simultaneous treatment with Val could prevent

DOX-induced myocardial injury by downregulating myocardial NOX

expression and reducing ROS production in rats (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Reagents

DOX was purchased from Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceutical

Co., Ltd. Val was purchased from Beijing Novartis Pharmaceutical

Co., Ltd. (https://www.novartis.com.cn/).

Animal model and study protocol

A total of 40 specific pathogen free-grade

8-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (body weight, 200–250 g) were

purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Dalian Medical

University. Rats were housed in 530 cm2 cages with

wood-shaving bedding (2 rats per cage) in a temperature-controlled

room (25±2°C), the humidity was maintained at 50–70%, the noise was

<85 decibels, with 14 h of light and 10 h of darkness every day.

Rats were fed under standard conditions with free access to food

and drinking water. Rats were randomly divided into three groups:

i) Control group (CON, n=8), rats treated with equal volume saline

daily via gavage for 6 weeks; ii) DOX group (n=18) rats received

intraperitoneal DOX (2.5 mg/kg) injection once per week for 6

weeks; iii) DOX+Val group (n=14), rats received intraperitoneal DOX

(2.5 mg/kg) injection once per week plus Val (20 mg/kg) daily via

gavage for 6 weeks. After another 4 weeks, surviving rats underwent

echocardiography examination. Subsequently, rats were sacrificed

under deep anesthesia (intramuscular ketamine hydrochloride

injection, 100 mg/kg), and the heart was isolated and weighed. The

atria and right ventricle were separated from the left ventricle

(LV), and the LV was cut into three sections along the LV long-axis

at a thickness of 3 mm. The middle section of the LV was processed

for histological examination. The basal and the apical sections

were stored at −80°C for immunohistological and biochemical

analysis. The experimental protocol is presented in Fig. 1. All experiments were performed in

compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines as well as the Guide for the

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Academy of

Sciences. The Institutional Animal Research and Ethics Committee of

Dalian University approved the protocols of the animal

experiments.

Echocardiography

Under light anesthesia (intramuscular ketamine

hydrochloride injection, 22 mg/kg), rats underwent echocardiography

using a Vivid E9 dimension system (General Electric Company),

equipped with a 12.0 MHz transducer. Two-dimensional and M-mode

echocardiography images were obtained in the parasternal long-axis

and short-axis views of the heart. All measurements were performed

online with optimal images from >10 cardiac cycles taken by an

experienced sonographer who was blinded to the study protocol and

grouping (24). Left ventricular

end-diastolic (LVEDD) and end-systolic diameters (LVESD) were

measured with M-mode in the parasternal short-axis images at the

papillary muscle level. Left ventricular fractional shortening

(LVFS) was calculated as follows: LVFS (%) = (LVEDD-LVESD)/LVEDD

×100. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated

according to the Teichholz formula (25).

Histopathological evaluation

The LV tissue assigned for histological examination

(middle section) was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C,

embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 5 µm slices and stained with

Masson (Shanghai Bogoo Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; http://www.bgswkj.com/) stain A for 15 min and stain B

for 20 min. Then, slices were stained with Picrosirius Red (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room

temperature and observed with a light microscope (magnification,

×100). Interstitial collagen volume fraction (CVF) was determined

using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.). CVF was

calculated as follows: CVF (%) = area of stained collagen/total

area of field of vision ×100.

ELISA

Specimens from left ventricular tissues of rats in

each group were weighed and cut into pieces, mixed with pre-cooled

PBS at a ratio of 1:9 (weight:volume) to prepare the tissue

homogenate. Myocardial levels of renin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA;

cat. no. RAB1162), TNF-α (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no.

RAB0479), IL-6 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. RAB0311), brain

natriuretic peptide (BNP; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no.

RAB0386), aldosterone (ALD; Abcam; cat. no. Ab136933),

malondialdehyde (MDA; Abcam; cat. no. Ab238537), ROS (Jianglai Bio;

http://www.laibio.com/; cat. no. JL21051),

superoxide dismutase (SOD; Jianglai Bio; cat. no. JL11065), NOX1

(Jianglai Bio; cat. no. JL36449), NOX2 (Jianglai Bio; cat. no.

JL50110) and NOX4 (Jianglai Bio; cat. no. JL23194) were measured.

ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol and a

DNA Eraser was used (Takara Bio, Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

All primer sequences were designed and synthesized

by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., which are presented in Table I. PrimeScript™ RT Reagent kit with

a gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Inc.) was used for reverse-transcription

at 37°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 sec. qPCR was performed using

SYBR®Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Inc.). qPCR was

performed as described previously (26). Briefly, qPCR was performed in 20 µl

reaction containing 10 µl SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus),

Bulk, 0.8 µl of each primer (10 µM), 0.4 µl ROX Reference Dye (50X)

and 4 µl dH2O and 2 µl cDNA. The thermocycling

conditions were: Pre-denaturation for 30 sec at 95°C; followed by

30 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Relative

quantities of all targets in test samples were normalized to the

respective GAPDH levels. 2−∆∆Cq was calculated as

follows (27): ∆Cq=DOX group

(target gene Cq value-made in Cq)-control group (target gene Cq

value-made in Cq value). For different groups of the genes, the

internal change ratio=2−∆∆Cq. The expression levels were

estimated using the integrated optical density (OD) of the positive

cells. Integrated OD was the average cumulative OD of the positive

staining area of each group determined by Image Pro Plus version

6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.). RT-qPCR experiments were performed

in triplicate.

| Table I.Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence

(5′→3′) |

|---|

| Bax | F:

GTGGTTGCCCTCTTCTACTTTG |

|

| R:

CCACAAAGATGGTCACTGTCTG |

| Collagen I | F:

CGGTGGTTATGACTTCAG CTTC |

|

| R:

AGAGGGCTGAGTGGGGAAC |

| BNP | F:

GCAGGCCAGCAGGGTCCACTACAC |

|

| R: GACCTC

GCCATTCCGCTGATTCT |

| Beclin-1 | F:

GACAAATCTAAGGAGTTGCCG |

|

| R:

AGAACTGTGAGGACACCCA |

| BCL2 | F:

AGTTCGGTGGGGTCATGTGTG |

|

| R:

CCAGGTATGCACCCAGAGTG |

| NOX4 | F:

GAACCCAAGTTCCAAGCTCA |

|

| R: GCA

CAAAGGTCCAGAAATCC |

| NOX1 | F:

GGCATCCCTTTACTCTGACCT |

|

| R:

TGCTGCTCGAATATGAATG |

| NOX2 | F:

TGTGCACCACGATGAGGAGAAAGATG |

|

| R:

ATTCTGGTGTTGGGGTGTGACTFGC |

| Caspase-3 | F: CTTTGCGCCATGCTG

AAACT |

|

| R:

TCAAATTCCGTGGCCACTT |

| MMP9 | F:

TCCCCAGAGCGTTACTCG CT |

|

| R: ACCTGG

TTCACCCGGTTGTG |

| MMP2 | F:

GAGTAAGAACAAGAAGACATACATC |

|

| R:

GTAATAAGCACCCTTGAA GAAATAG |

| ANP | F: GGGTGTGAACCA

CGAGAAAT |

|

| R:

ACTGTGGTCATGAGCCCTTC |

| β-MHC | F: GGGCAA

AGGCAAAGCAAAGA |

|

| R:

AAAGTGAGGGTGCGTGGAGC |

| BGN | F:

ACAACAAGCTGTCCCGGGTG |

|

| R: AGC

CCATGGGGCAGAAATCG |

| TPM1 | F:

GCTGGTTGAGGAGGAGTT |

|

| R:

ACTTGTTCGTCACCGTTT |

| Collagen III | F:

GGAGTCGGAGGAATGGGTG |

|

| R:

ATTGCGTCCATCAAAGCCTC |

| CORIN | F: GTACAG

TGCGGTGTCCAACA |

|

| R:

ATCCTGTCAATCCTACCCCC |

| TGF-β1 | F:

CCAACTATTGCTTCAGCTCCA |

|

| R:

GTGTCCAGGCTCCAAATGT |

| GDF15 | F:

CTGCTCTTGCTGCTTCTGCT |

|

| R:

TCGTCCGGGTTGAGTTGG |

| POSTN | F:

AGGAGCCGTGTTTGAGACCAT |

|

| R: CGGTGAAAGTGGTTT

GCTGTTT |

| GAPDH | F:

GGTGCTGAGTATGTCGTGGAGT |

|

| R: CACAGT

CTTCTGAGTGGCAGTG |

Western blot analysis

Myocardial protein expression levels of NOX1, NOX2

and NOX4 were determined by western blotting as described

previously (28). Extracted

membrane proteins from LV tissue was quantified using a BCA protein

assay kit and protein (25 µg/lane) was separated via SDS-PAGE on a

20% gel, and subsequently transferred to a polyvinylidene

difluoride membrane. Then, the membrane was blocked with 5% BSA

blocking buffer (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 1 h, and incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit

anti-human NOX1 (1:5,000; cat. no. GTX103888), rabbit anti-human

NOX2 (1:5,000; cat. no. GTX133715) and rabbit anti-human NOX4

antibodies (1:1,000; cat. no. GTX121929; all purchased from

GeneTex, Inc.), and the loading control rabbit anti-human

Na+/K±ATPase α-1 antibodies (1:10,000; cat.

no. ab76020; Abcam), followed by secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG

(1:5,000; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) or at room temperature for 1.5 h.

The signal was developed by applying goat anti-rabbit IgG

conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, and thereafter exposed to

X-ray films that were scanned and determined by ImageJ software

v1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health) to quantify protein

expression.

In vitro experiments

Cell culture

H9C2 cardiomyocytes (China Center for Type Culture

Collection) were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with

5% CO2. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (AusGeneX,

Ltd.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 0.25%

trypsin and 0.02% EDTA digestive solution were used to trypsinize

the cells. After the third passage, H9C2 cells were harvested for

further experiments.

Downregulation of NOX2 and NOX4 via

small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

siRNA targeting NOX2 (20 µM; 10 µl/well), siRNA

targeting NOX4 (20 µM; 10 µl/well) and the negative random siRNA

(20 µM; 10 µl/well; Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) were transiently

transfected into H9C2 cells (1×105/well) using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

according to the manufacturer's protocols and a previous study

(29). The sequences of the siRNAs

were as follows: NOX2-rat-663 siRNA sense,

5′-CCAUGGAGCUGAACGAAUUTT-3′ and anti-sense,

5′-AAUUCGUUCAGCUCCAUGGTT-3′; and NOX4-rat-576 siRNA sense,

5′-GCUUCUACCUAUGCAAUAATT-3′ and anti-sense,

5′-UUAUUGCAUAGGUAGAAGCTT-3′.

Upregulation of NOX2 and NOX4 via

construction and transfection of eukaryotic overexpression

plasmids

Total RNA was extracted from cultured H9C2 cells

using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

cDNA was synthesized and the PCR product was inserted into a

pMD18-T plasmid (Takara Bio, Inc.). Insertion was confirmed using

the restriction enzymes XhoI and KpnI (Takara Bio,

Inc.) and DNA sequencing. The NOX2 and NOX4 genes were cloned into

a pEX-4 (pGCMV/MCS/T2A/EGFP/Neo) vector (Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd.). Recombinant plasmids were obtained and identified by

digestion with XhoI and KpnI. The following primers

were designed with specific restriction enzyme sites to clone the

complete coding region of NOX2 and NOX4: NOX2 forward,

5′-GCGCTACCGGACTCAGATCTCGAGGCCACCATGGGGAACTGGGCTGTGAATGAGGGACTC-3′

(XhoI) and reverse,

5′-ACTTCCTCTGCCCTCGGTACCGAAGTTTTCCTTGTTGAAGATGAAGTGGACTCCACGTGG-3′

(KpnI); and NOX4 forward,

5′-GCTACCGGACTCAGATCTCGAGGCCACCATGGCGCTGTCCTGGAGGAGCTGGCTGGCCAA-3′

(XhoI) and reverse,

5′-ACTTCCTCTGCCCTCGGTACCGCTGAAAGATTCTTTATTGTATTCAAATTTTGTCCCATA-3′

(KpnI). The optimized PCR amplification conditions were:

Annealing at 58°C and extension at 72°C for 35 cycles. H9C2 cells

(1×105/well) were transfected with pEX-4-NOX2/NOX4 (1

µg/µl; 2.5 µl/well) or empty vectors (1 µg/µl; 2.5 µl/well), which

was added to balance the total amount of transfected DNA using

Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's protocols and a

previous study (30).

Untransfected cells were used as controls. Cells were cultured for

24 h before use in subsequent experiments.

Cell viability

H9C2 cells (3×104/well) were treated with

DOX (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 10, 30 or 50 µM) and Val (0.1, 0.5, 1,

3, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 or 30 µM) for 12, 24, 48 or 72 h) with 5%

CO2, at 37°C in an incubator, and subsequently harvested

for further molecular and biochemical analyses. Untreated H9C2

cells and DMSO-pre-treated H9C2 cells were used as the control

groups. All in vitro experiments were performed in

triplicate. Cell viability was determined using a modified MTT

assay as described previously (31). Briefly, MTT solution in PBS (5

mg/ml) was added to each well at a final concentration of 0.05%.

After 3 h, the formazan precipitate was dissolved in DMSO. The

absorbance was measured at 570 and 620 nm (background) using

Epoch™microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

In vitro measurement of intracellular

ROS production

To measure intracellular ROS production, H9C2 cells

(6×104/well) were seeded in a 24-well culture plate and

incubated with dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; 10 mM;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. After the

various aforementioned treatments, cells were washed immediately

and resuspended in PBS solution. Viable cells incorporate

2′,7′-DCFH-DA, which is not fluorescent, but in the presence of

ROS, DCFH-DA reacts with oxygen species to produce the fluorescent

dye 2′,7′-DCF. Fluorescence emission was measured by flow cytometry

(BD FACSCanto™ II Flow Cytometer; BD Biosciences) using a 525 nm

band pass filter, which provides an index of the intracellular

oxidative metabolism (32). ROS

levels were detected by performing a DCFH assay and

semi-quantitative analysis (BD FACSDiva software; version 7.0; BD

Biosciences). The cells were divided into ten groups and treated as

follows: i) Control group included H9C2 cells without any

treatment; ii) H9C2 cells exposed to 1 µM DOX for 24 h; iii) cells

exposed to 5 µM Val for 1 h; iv) cells pre-treated with 5 µM Val

for 1 h followed by treatment with 1 µM DOX for 24 h; v) cells

transiently transfected with NOX2-siRNA for 24 h followed by

treatment with 1 µM DOX for 24 h; vi) cells transiently transfected

with NOX4-siRNA for 24 h followed by treatment with 1 µM DOX for 24

h; vii) cells transiently transfected with negative siRNA for 24 h

followed by treatment with 1 µM DOX for 24 h; viii) cells

transiently transfected with an empty vector for 24 h; ix)

NOX2-overexpressing cells treated with 1 µM DOX for 24 h; and x)

NOX4-overexpressing cells were treated with 1 µM DOX for 24 h.

Apoptosis and flow cytometry

Cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated using flow

cytometry and DNA electrophoresis. A total of 1×105 H9C2

cells/well were seeded in 12-well culture plates and cardiomyocytes

under various treatments were trypsinized, washed with PBS

solution, centrifuged at 800 × g for 6 min at 4°C, resuspended in

ice-cold 70% ethanol/PBS, centrifuged at 800 × g for another 6 min

at 4°C, and resuspended in PBS. Cells were then incubated with

propidium iodide (PI) and FITC-labeled Annexin V for 30 min at

37°C. Cells were washed to remove excess PI and Annexin V, and then

analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences) with a 488 nm argon laser light source, a 525 nm band

pass filter for FITC fluorescence, and a 625 nm band pass filter

for PI-fluorescence. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using

CellQuest software version 3.0 (BD Biosciences). Dot plots of PI

fluorescence (y-axis) vs. FITC fluorescence (x-axis) are presented.

The assessment of apoptosis rate was the sum of early and late

apoptosis. Apoptosis analysis was performed in the aforementioned

ten groups that were used to measure intracellular ROS

production.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

and were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's pos hoc comparisons using SPSS software (version 20.0;

IBM Corp.). Kaplan-Meier curves were used to plot and estimate

survival. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

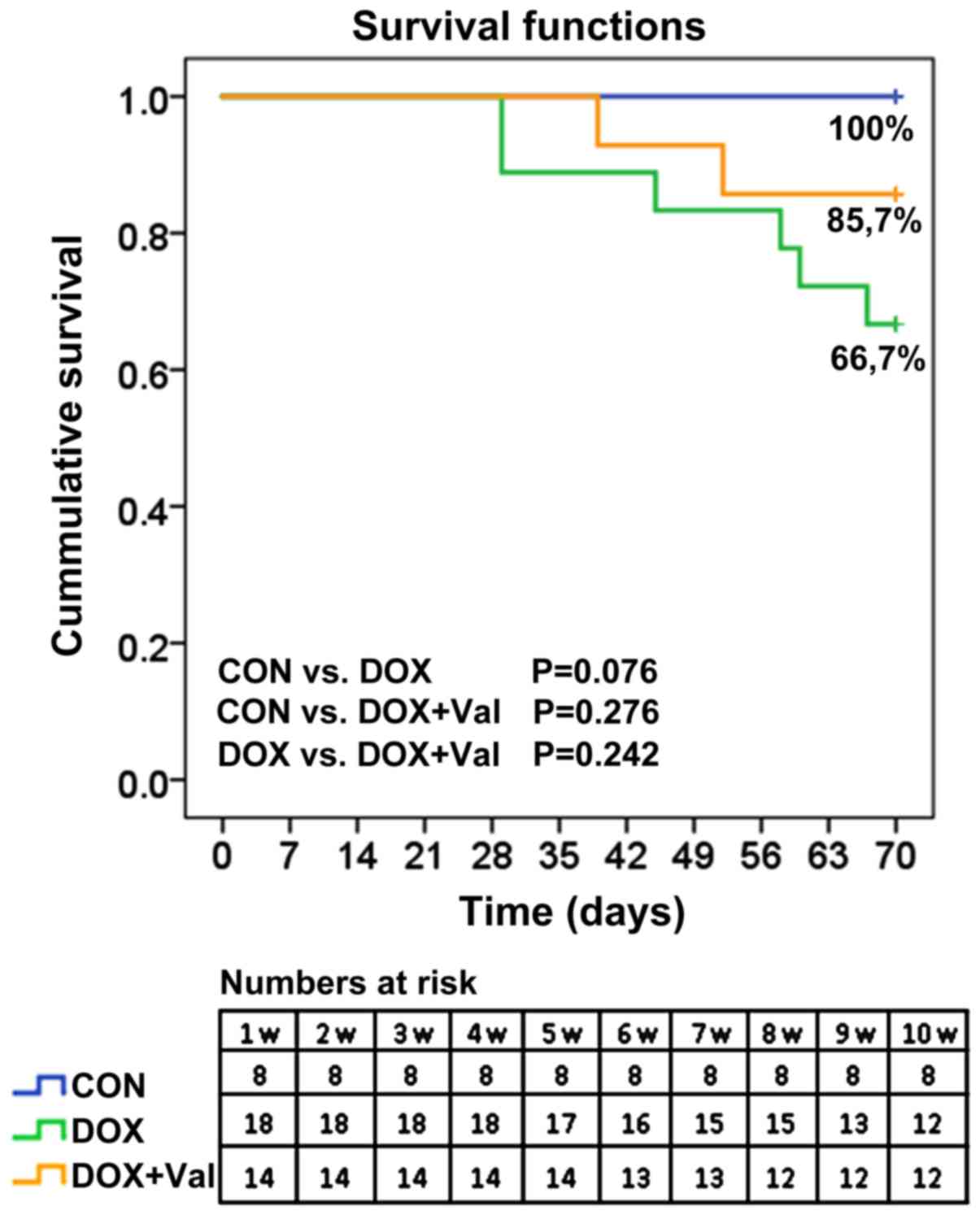

Cumulative survival rates of rats

All rats (n=8) in the CON group survived to the end

of the study. In the DOX group, 16 of the 18 (88.9%) rats were

alive at week 7 and 12 (66.7%) rats were alive at week 10. In the

DOX+Val group, 13 of the 14 (92.9%) rats were alive at week 6 and

12 (85.7%) rats were alive at week 10 (Fig. 2).

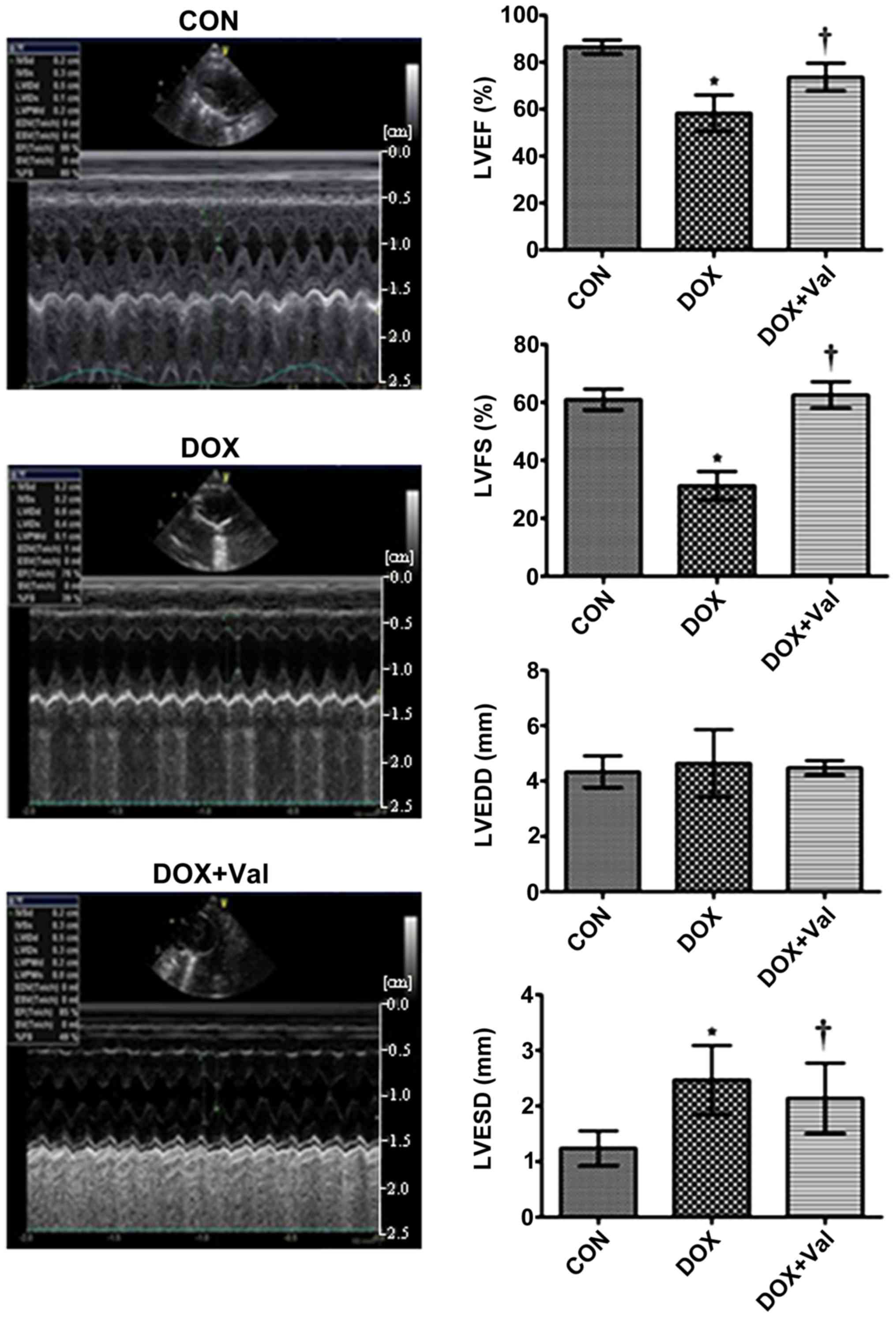

Effect of DOX+Val on LV function and

CVF

At week 10 of the study, LVEF and LVFS were

significantly lower, whereas LVESD was significantly higher in the

DOX group compared with the CON group. LVEF and LVFS were

significantly higher and LVESD was significantly lower in the

DOX+Val group compared with the DOX group (Fig. 3).

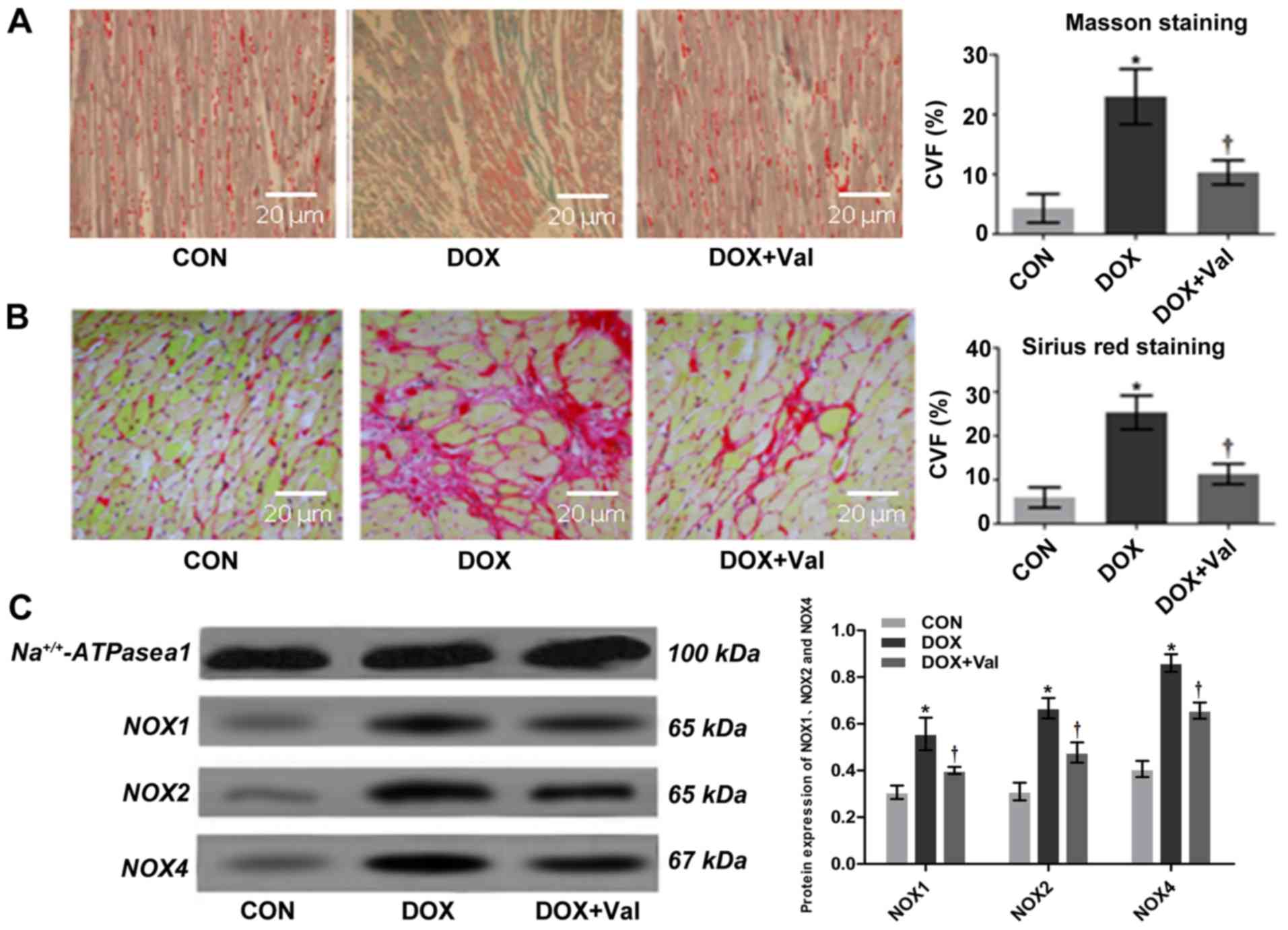

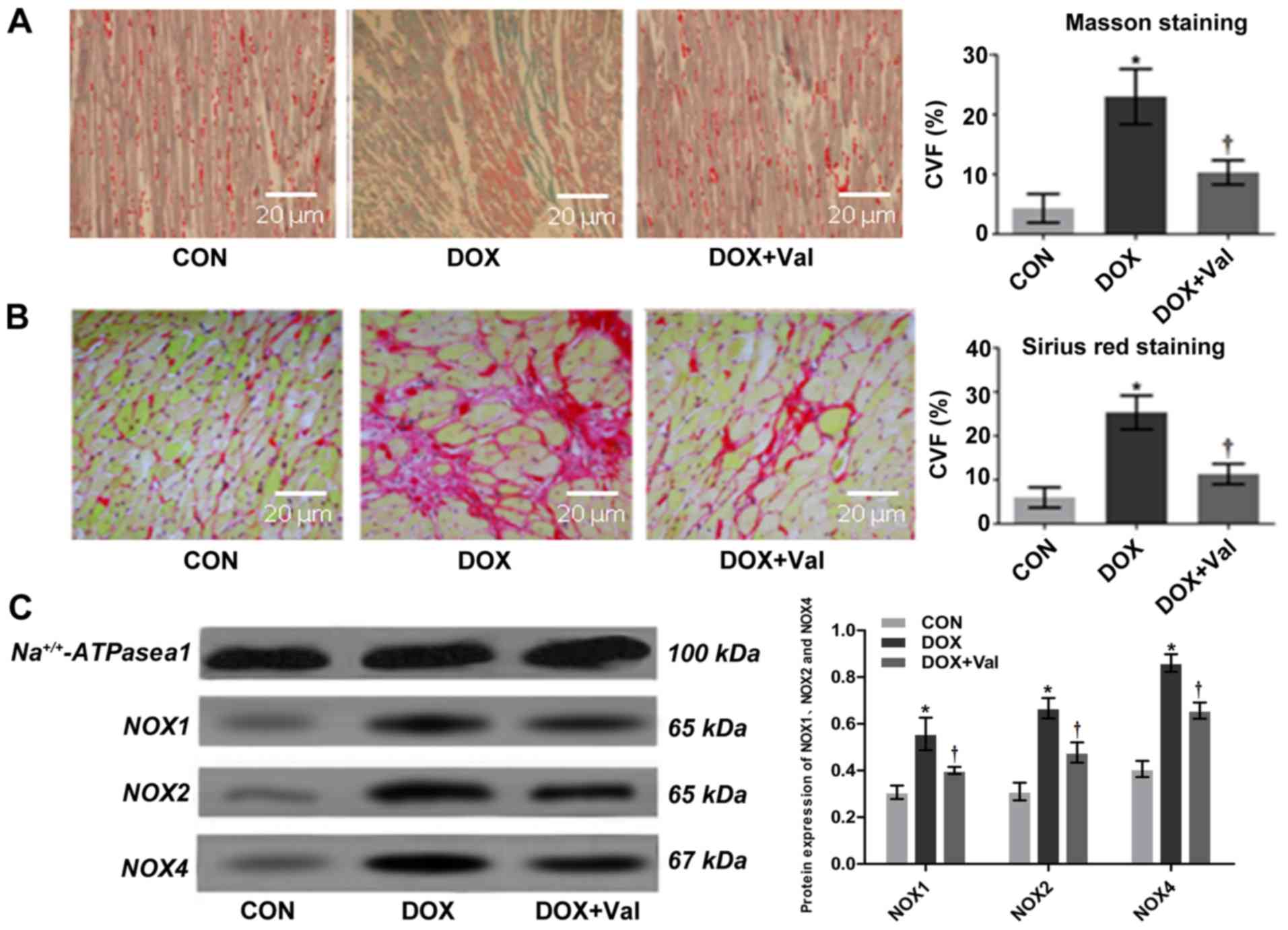

Interstitial CVF values measured using Masson

staining and Sirius Red staining were significantly higher in the

DOX group compared with the CON group. In the DOX+Val group, the

values were significantly lower compared with the DOX group

(Fig. 4A and B). Overall, these

results suggest that simultaneous application of Val with DOX

attenuated DOX-induced myocardial injury in rats, as shown by

improved cardiac function and attenuated cardiac remodeling.

| Figure 4.Myocardial histopathology and protein

expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4. (A) Masson staining and CVF

(magnification, ×200). (B) Sirius red staining and CVF

(magnification, ×200). Collagen stained with Masson staining (blue)

and Sirius red staining (red) are significantly increased in the

DOX group compared with those in the CON group, which is attenuated

in the DOX+Val group. (C) Myocardial protein expression of NOX1,

NOX2 and NOX4 detected by western blotting. *P<0.05 vs. CON;

†P<0.05 vs. DOX.CON, control; DOX, doxorubicin; Val,

valsartan; NOX, NAD(P)H oxidase; CVF, collagen volume fraction. |

Effect of DOX+Val on myocardial mRNA

expression levels of various signaling molecules

The myocardial mRNA expression levels of NOX2, NOX4,

Bax, Caspase-3, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)2, MMP9,collagen I,

Beclin-1, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), atrial natriuretic

peptide (ANP), β myosin heavy chain (β-MHC), growth differentiation

factor 15 (GDF15), tropomyosin 1 (TPM1), biglycan (BGN) and

periostin (POSTN) were significantly lower in the DOX+Val group,

whereas the mRNA expression levels of BCL2 and collagen III were

significantly higher in the DOX+Val group compared with the DOX

group (all P<0.05; Table II).

Myocardial mRNA expression levels of NOX1, atrial natriuretic

peptide-converting enzyme (CORIN) and transforming growth factor

(TGF)-β1 were similar between DOX and DOX+Val groups. The results

suggested that the simultaneous application of Val with DOX could

reduce the DOX-induced myocardial mRNA expressions of various

NAD(P)H oxidase, apoptosis and collagen signaling molecules, and

increase the mRNA expression levels of anti-apoptotic signaling

molecule in rats.

| Table II.mRNA expression of myocardial genes

in CON (n=8), DOX (n=12) and DOX+Val (n=12) groups. |

Table II.

mRNA expression of myocardial genes

in CON (n=8), DOX (n=12) and DOX+Val (n=12) groups.

| Gene | CON (mean ±

SD) | DOX (mean ±

SD) | DOX+Val (mean ±

SD) |

|---|

| Bax |

0.005472±0.002241 |

0.579347±0.015441a |

0.016487±0.002301a,b |

| Collagen I |

0.000159±0.000117 |

0.003708±0.001421a |

0.000743±0.000246a,b |

| BNP |

0.008863±0.000374 |

0.033877±0.011124a |

0.015468±0.003612b |

| Beclin-1 |

0.070218±0.038941 |

0.496883±0.027112a |

0.408002±0.014891a,b |

| BCL2 |

0.069447±0.024328 |

0.005516±0.002308a |

0.011095±0.006306b |

| NOX4 |

2.660319±0.722017 |

23.744164±9.831247a |

4.283176±0.274911a,b |

| NOX1 |

0.329351±0.027661 |

0.715372±0.196175a |

0.616009±0.201272 |

| NOX2 |

0.005916±0.002794 |

0.085991±0.008259a |

0.008974±0.000806a,b |

| Caspase-3 |

0.000813±0.000582 |

0.004873±0.003057a |

0.002485±0.001034a,b |

| MMP9 |

0.000110±0.000222 |

0.001814±0.000453a |

0.000134±0.000177a,b |

| MMP2 |

0.106209±0.082461 |

0.409883±0.172409a |

0.160207±0.036443a,b |

| ANP |

1.263391±0.404303 |

7.823333±2.880115a |

2.786022±0.582717a,b |

| β-MHC |

1.473521±0.610019 |

24.508593±9.604317a |

3.712543±1.140049a,b |

| BGN |

3.914408±0.593123 |

0.594062±0.097032a |

0.038563±0.004427a,b |

| TPM1 |

0.007855±0.003824 |

0.002717±0.001296a |

0.000702±0.000241a,b |

| Collagen III |

0.017781±0.003225 |

0.000461±0.000158a |

0.001982±0.000791a,b |

| CORIN |

0.245495±0.074003 |

0.030678±0.028541a |

0.016321±0.008023a |

| TGF-β1 |

0.013657±0.004844 |

0.039625±0.011513a |

0.022389±0.012937 |

| GDF15 |

0.003563±0.001879 |

0.044461±0.013455a |

0.004693±0.000264a,b |

| POSTN |

0.003533±0.002247 |

0.530036±0.110447a |

0.020532±0.006552a,b |

Effect of DOX+Val on myocardial

protein expression levels of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4

Myocardial protein expression levels of NOX1, NOX2

and NOX4 were significantly higher in the DOX treated group

compared with the CON group, whereas the expression levels were

significantly lower in the DOX+Val group compared with the DOX

group (all P<0.05; Fig. 4C).

The results indicated that simultaneous application of Val with DOX

resulted in a reduction of DOX-induced myocardial protein

expression levels of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4. Myocardial levels of

renin, ALD, TNF-α, IL-6, BNP, ROS, MDA, SOD, NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4

were measured using ELISA (Table

III). Myocardial levels of renin, ALD, TNF-α, IL-6, BNP, ROS,

MDA, NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 were significantly higher in the DOX group

compared with the CON group (all P<0.05), and the levels of

these factors were significantly lower in the DOX+Val group

compared with the DOX group (all P<0.05). Myocardial SOD levels

were significantly lower in the DOX group compared with the CON

group, and significantly higher in the DOX+Val group compared with

the DOX group (both P<0.05). These results suggest that

simultaneous application of Val with DOX decreased DOX-induced

changes in the myocardial levels of renin, ALD, TNF-α, IL-6, BNP,

ROS, MDA, NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 and increased SOD levels.

| Table III.Myocardial content of genes in CON

(n=8), DOX (n=12) and DOX+Val (n=12) groups. |

Table III.

Myocardial content of genes in CON

(n=8), DOX (n=12) and DOX+Val (n=12) groups.

| Protein, ng/ml | CON (mean ±

SD) | DOX (mean ±

SD) | DOX+Val (mean ±

SD) |

|---|

| Renin | 27.27±2.32 |

41.82±3.76a |

34.02±3.14a,b |

| ALD | 246.55±68.03 |

376.87±85.34a |

264.25±71.05b |

| MDA | 2.55±0.72 |

3.99±0.93a |

2.72±0.77b |

| SOD | 144.61±32.15 |

105.48±22.65a |

138.84±18.16b |

| ROS | 275.42±71.86 |

355.64±100.17a |

327.41±69.88b |

| TNF-α | 173.52±20.88 |

260.24±23.47a |

211.77±20.59b |

| IL-6 | 77.09±17.26 |

88.28±21.73a |

73.27±15.15b |

| BNP | 208.31±33.62 |

331.77±22.45a |

275.73±26.21a,b |

| NOX1 | 59.77±8.94 |

68.87±10.16a |

59.13±7.65b |

| NOX2 | 44.22±9.55 |

51.41±7.31a |

49.21±3.80b |

| NOX4 | 21.76±5.76 |

27.37±6.41a |

21.08±5.49b |

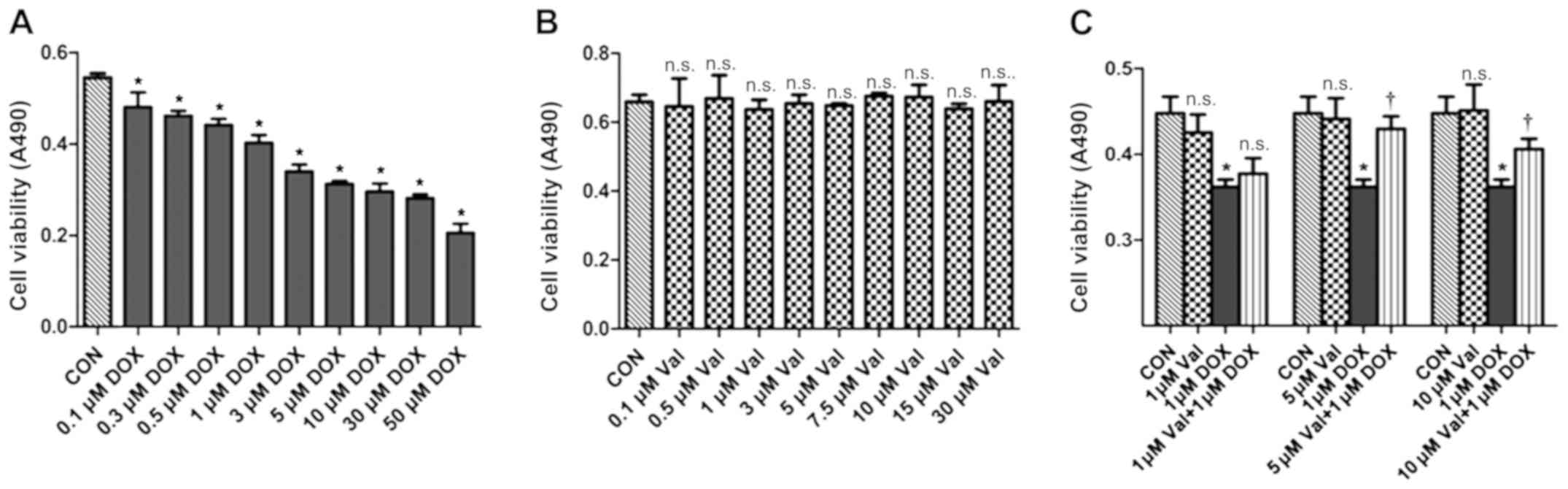

Effect of DOX+Val on cell

viability

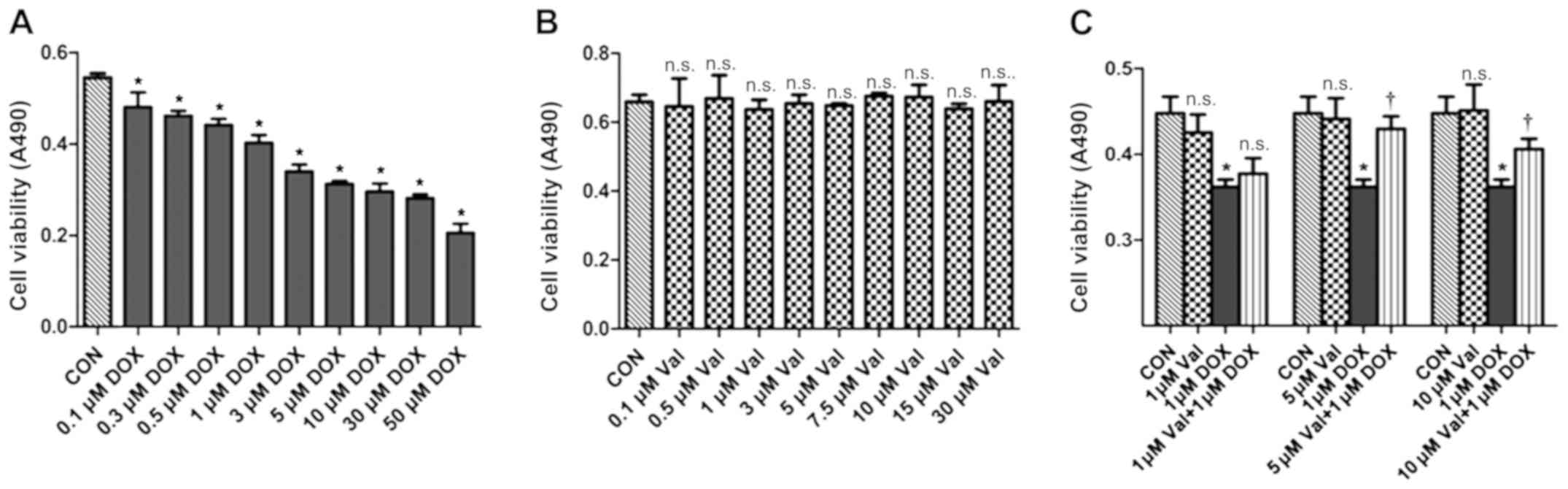

H9C2 cells were treated with various concentrations

of DOX (0.1–50 µM) for 24 h. DOX treatment resulted in decreased

cell viability in a dose-dependent manner, and cell viability was

significantly decreased by 1 µM DOX treatment. Thus, 1 µM DOX was

chosen as the target dose for subsequent experiments (Fig. 5A). H9C2 cells were also treated

with various concentrations of Val (0.1–30 µM) for 24 h, and the

results showed that Val did not affect cell survival (Fig. 5B). As shown in Fig. 5C, DOX-induced H9C2 cytotoxicity was

significantly attenuated after 1 h of pre-treatment with 5 and 10

µM/l Val.

| Figure 5.Cell viability measured by MTT assay.

(A) H9C2 cells were treated with various concentrations of DOX for

24 h, DOX resulted in cell death in a dose-dependent manner. Cell

viability significantly decreased with 1 µM DOX, so this

concentration was chosen as the target dose. (B) H9C2 cells were

treated with numerous concentrations of Val, the results revealed

that the nine different concentrations of Val did not affect the

survival of H9C2 cells within 24 h. (C) Val concentration required

to protect against DOX-induced cytotoxicity was calculated by

performing a dose-response study in the presence of 1, 5 and 10 µM

Val. The cytotoxic effects of DOX were significantly attenuated by

pre-treatment with 5 and 10 µM Val. Based on these results, 5 µM

Val was selected as the target dose for further study. *P<0.05

vs. CON; †P<0.05 vs. DOX; n.s., not significant. CON,

control; DOX, doxorubicin; Val, valsartan; NOX, NAD(P)H

oxidase. |

Verification of transfection efficacy of siRNA and

OE vector. As presented in Fig.

S1, NOX2 and NOX4 mRNA expressions in the negative siRNA group

and Empty vector group were similar with the Control group. It was

apparent that the designed siRNA, vector and transfection process

do not affect the expression of the targeted gene in H9c2 cells.

The expressions of NOX2 and NOX4 in NOX2 siRNA group and NOX4 siRNA

groups were significantly lower compared with the negative siRNA

group, and their expressions in the NOX2 OE group and NOX4 OE group

were significantly higher compared with the Empty vector group.

These results indicated that siRNA and OE vectors transfection is

high effective.

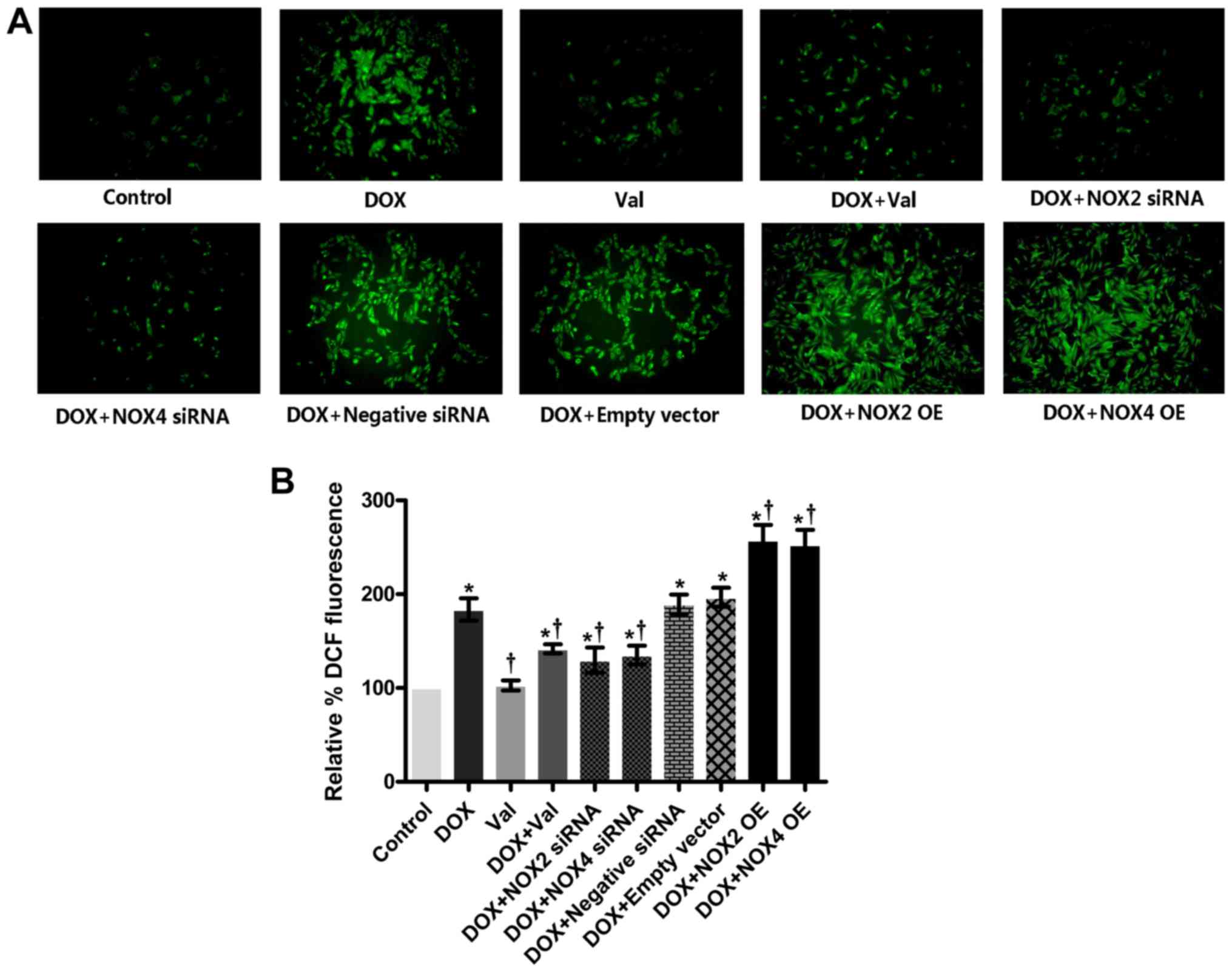

Effect of DOX+Val on intracellular ROS

production in vitro

As shown in Fig. 6A and

B, intracellular ROS production was significantly increased in

the DOX-treated H9C2 cells compared with the CON group. ROS

production was significantly reduced in the DOX+Val-treated H9C2

cells compared with the DOX group. Similarly, intracellular ROS

production in the DOX-treated H9C2 cells was significantly reduced

by knockdown of NOX2 and NOX4, and intracellular ROS production in

the DOX-treated H9C2 cells was further increased following NOX2 and

NOX4 overexpression. Intracellular ROS production in DOX-treated

H9C2 cells was not significantly affected by the control siRNA or

empty vector transfection.

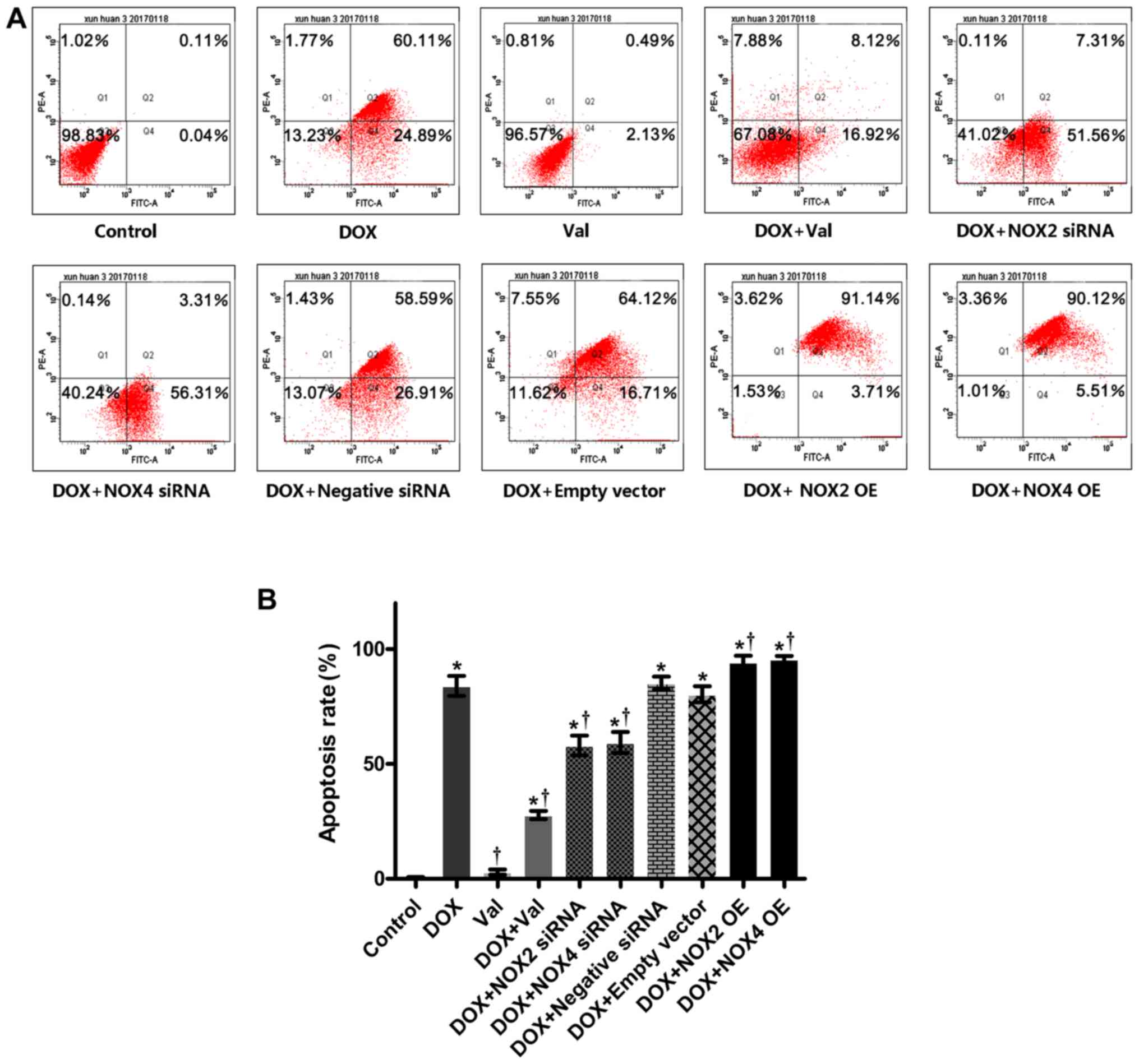

Effect of DOX+Val on cardiomyocyte

apoptosis

As shown in Fig. 7A and

B, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was significantly increased in the

DOX-treated H9C2 cells compared with the CON group. Apoptosis was

significantly reduced by DOX+Val treatment, as well as NOX2 and

NOX4 knockdown. Apoptosis rates in the DOX-treated H9C2 cells were

further increased following NOX2 and NOX4 overexpression.

Cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the DOX-treated H9C2 cells was not

affected by the control siRNA or empty vector transfection.

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that a

combined treatment of Val and DOX significantly attenuated

DOX-induced myocardial injury and reduced DOX-induced ROS

production and apoptosis, potentially via downregulation of the

NOX2/NOX4 signaling pathway.

In agreement with previous studies (7,33–35),

it was shown that simultaneous application of Val with DOX

attenuated DOX-induced myocardial injury in rats, as shown by the

improvement in cardiac function and reduction in cardiac

remodeling. Compared with the CON group, the CVF was significantly

increased, along with upregulated expression of MMP2, MMP9 and

collagen I in the DOX group, suggesting enhanced fibrosis was

responsible for reduced cardiac function in this model. Treatment

with Val and DOX significantly reversed the aforementioned changes

induced by DOX, suggesting that Val protected the rats from

DOX-induced myocardial injury by reducing collagen remolding and

myocardial fibrosis, possibly by downregulating myocardial

expression of MMP2, MMP9 and collagen I. This result is in

agreement with a previous study that demonstrated that

co-administration of telmisartan with DOX decreased the levels of

cardiotoxicity-associated biochemical markers (lactate

dehydrogenase and creatine kinase myocardial band) and attenuated

the effects of DOX on oxidative stress parameters and nitric oxide

production, as well as myocardial fibrosis (36). Taken together, these results

suggest that application of ARBs with DOX at the time of drug

initiation may be a clinically feasible strategy to

prevent/attenuate the potential cardiac damage induced by DOX in

patients with tumors.

Increased ROS production and reduced SOD levels are

frequently observed pathological features of various cardiovascular

diseases, such as atherosclerosis and hypertension (37,38).

In the present study, MDA levels were increased and SOD levels were

decreased in myocardial tissues from the DOX-treated rats in

vivo, and increased ROS production and apoptosis were observed

in the DOX-treated H9C2 cells in vitro. Similarly,

simultaneous treatment with Val significantly reversed these

changes both in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, it

was shown that mRNA expression levels of the pro-apoptotic genes

Caspase-3 and Bax were upregulated, whereas the mRNA expression

levels of BCL2 were downregulated in the DOX group, and Val

treatment reversed these changes. Taken together, these results

suggest that treatment with Val may effectively reduce the enhanced

myocardial apoptosis induced by DOX, possibly through modulating

the expression of apoptosis-related genes. Additionally, these

results suggest that the beneficial effects of Val in this model

are at least partly associated with the capacity of Val to reduce

DOX-induced myocardial injury via the reduction of myocardial

apoptosis.

The myocardial mRNA and protein expression levels of

NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 following DOX treatment were measured. The

results showed that DOX treatment significantly upregulated the

myocardial protein expression of NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4, and mRNA

expression of NOX2 and NOX4. Simultaneous treatment with Val

significantly reduced the mRNA expression levels of NOX2 and NOX4,

as well as the myocardial protein expression levels of NOX1, NOX2

and NOX4. These results suggest that upregulated NOX expression

levels, particularly NOX2 and NOX4 signaling, may contribute to

DOX-induced cardiac injury, and the observed beneficial effects of

simultaneous application of Val may partially be associated with

its capacity to downregulate NOX2 and NOX4 signaling in this

model.

To explore the mechanism underlying the protective

effects of Val in DOX-induced myocardial injury, ROS production and

apoptosis of DOX-treated H9C2 cells were observed following up- or

downregulation of NOX2 and NOX4 expression, as Val significantly

downregulated the myocardial mRNA expression of these two genes.

The results suggested that ROS production and apoptosis were

significantly reduced by downregulating NOX2 and NOX4, whereas

overexpression of NOX2 and NOX4 increased ROS production and

apoptosis in DOX-treated H9C2 cells, suggesting that downregulation

of NOX2 and NOX4 expression may be mechanism by which Val

alleviates DOX-induced myocardial injury. Although the present

study observed changes in intracellular ROS and cardiomyocyte

apoptosis under the conditions of NOX-overexpressing and

NOX-silencing, we did not detect them at the protein level, which

is a limitation of this study. In our previous study examining the

mechanisms of DOX toxicity, the expression of angiotensin (Ang)II

receptor protein (AT1R) was significantly upregulated following DOX

stimulation in H9C2 cells, and AngII increased the protein

expression levels of NOX2 and NOX4 and the production of ROS (data

not yet published). The protein expression levels of ERK, JNK and

P38, which lie downstream of the mitogen-activated protein kinase

(MAPK) signaling pathway, were increased significantly (data not

yet published). Pre-treatment with Val reduced the expression of

AT1R, NOX2, NOX4 and ROS, and activity of the MAPK signaling

pathway was decreased (data not yet published). Thus, it was

hypothesized that the AngII-NOX-ROS-MAPK signaling pathway may

underlie DOX-induced myocardial toxicity.

In summary, co-treatment with Val and DOX

significantly reduced DOX-induced myocardial injury, potentially

through downregulation of NOX2 and NOX4 signaling. The present

study provides experimental evidence supporting the simultaneous

use of ARBs to prevent DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in the clinical

setting.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural

Science Funds of Liaoning Province (grant no. 201602033) and the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

81770405).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

DC, LC and WT performed the experiments and data

analysis, and prepared the manuscript. HW and QW contributed to the

conception and design of the study and critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content and supervised the

experimental process. LM and ZL prepared the figures, and analyzed

and interpreted the data. QY designed this study and proofread the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experiments were performed in compliance with

the ARRIVE guidelines as well as the Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals of the National Academy of Sciences. The

Institutional Animal Research and Ethics Committee of Dalian

University approved the protocols of the animal experiments.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Razavi-Azarkhiavi K, Iranshahy M, Sahebkar

A, Shirani K and Karimi G: The protective role of phenolic

compounds against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: A

comprehensive review. Nutr Cancer. 68:892–917. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Swain SM, Whaley FS and Ewer MS:

Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: A

retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 97:2869–2879. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ganame J, Claus P, Uyttebroeck A, Renard

M, D'hooge J, Bijnens B, Sutherland GR, Eyskens B and Mertens L:

Myocardial dysfunction late after low-dose anthracycline treatment

in asymptomatic pediatric patients. J Am Soc Echocardiogr.

20:1351–1358. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tebbi CK, London WB, Friedman D, Villaluna

D, De Alarcon PA, Constine LS, Mendenhall NP, Sposto R, Chauvenet A

and Schwartz CL: Dexrazoxane-associated risk for acute myeloid

leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome and other secondary malignancies

in pediatric Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol. 25:493–500. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Shaikh AY and Shih JA:

Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. Curr Heart Fail Rep.

9:117–127. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Iqbal M, Dubey K, Anwer T, Ashish A and

Pillai KK: Protective effects of telmisartan against acute

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Pharmacol Rep.

60:382–390. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zong WN, Yang XH, Chen XM, Huang HJ, Zheng

HJ, Qin XY, Yong YH, Cao K, Huang J and Lu XZ: Regulation of

angiotensin-(1–7) and angiotensin II type 1 receptor by telmisartan

and losartan in adriamycin-induced rat heart failure. Acta

Pharmacol Sin. 32:1345–1350. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Angsutararux P, Luanpitpong S and

Issaragrisil S: Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: Overview of

the roles of oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2015:7956022015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chang SA, Lim BK, Lee YJ, Hong MK, Choi JO

and Jeon ES: A Novel Angiotensin Type I receptor antagonist,

fimasartan, prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. J

Korean Med Sci. 30:559–568. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Manohar P and Pina IL: Therapeutic role of

angiotensin II receptor blockers in the treatment of heart failure.

Mayo Clin Proc. 78:334–338. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nakamae H, Tsumura K, Terada Y, Nakane T,

Nakamae M, Ohta K, Yamane T and Hino M: Notable effects of

angiotensin II receptor blocker, valsartan, on acute cardiotoxic

changes after standard chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone. Cancer. 104:2492–2498.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sakr HF, Abbas AM and Elsamanoudy AZ:

Effect of valsartan on cardiac senescence and apoptosis in a rat

model of cardiotoxicity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 94:588–598. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen L, Yan KP, Liu XC, Wang W, Li C, Li M

and Qiu CG: Valsartan regulates TGF-β/Smads and TGF-β/p38 pathways

through IncRNA CHRF to improve doxorubicin-induced heart failure.

Arch Pharm Res. 41:101–109. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hafstad AD, Nabeebaccus AA and Shah AM:

Novel aspects of ROS signalling in heart failure. Basic Res

Cardiol. 108:3592013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dietl A and Maack C: Targeting

mitochondrial calcium handling and reactive oxygen species in heart

failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 14:338–349. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Meitzler JL, Antony S, Wu Y, Juhasz A, Liu

H, Jiang G, Lu J, Roy K and Doroshow JH: NADPH oxidases: A

perspective on reactive oxygen species production in tumor biology.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 20:2873–2889. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bedard K and Krause KH: The NOX family of

ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: Physiology and pathophysiology.

Physiol Rev. 87:245–313. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S and Matsushima S:

Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol. 301:H2181–H2190. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao QD, Viswanadhapalli S, Williams P,

Shi Q, Tan C, Yi X, Bhandari B and Abboud HE: NADPH oxidase 4

induces cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy through activating

Akt/mTOR and NFκB signaling pathways. Circulation. 131:643–655.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ruzicka M, Yuan B, Harmsen E and Leenen

FH: The renin-angiotensin system and volume overload-induced

cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Effects of angiotensin converting

enzyme inhibitor versus angiotensin II receptor blocker.

Circulation. 87:921–930. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bendall JK, Cave AC, Heymes C, Gall N and

Shah AM: Pivotal role of a gp91(phox)-containing NADPH oxidase in

angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circulation.

105:293–296. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Murdoch CE, Zhang M, Cave AC and Shah AM:

NADPH oxidase-dependent redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy,

remodelling and failure. Cardiovasc Res. 71:208–215. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Seddon M, Looi YH and Shah AM: Oxidative

stress and redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart

failure. Heart. 93:903–907. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Watson LE, Sheth M, Denyer RF and Dostal

DE: Baseline echocardiographic values for adult male rats. J Am Soc

Echocardiogr. 17:161–167. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Barauna VG, Rosa KT, Irigoyen MC and de

Oliveira EM: Effects of resistance training on ventricular function

and hypertrophy in a rat model. Clin Med Res. 5:114–120. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu HN, Wang HR, Cheng D, Pei ZW, Zhu N

and Yu Q: Potential role of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17

(ADAM17) in age-associated ventricular remodeling of rats. RSC

Advances. 9:14321–14330. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ye L, Haider HKH, Jiang S, Ge R, Law PK

and Sim EK: In vitro functional assessment of human skeletal

myoblasts after transduction with adenoviral bicistronic vector

carrying human VEGF165 and angiopoietin-1. J Heart Lung Transplant.

24:1393–1402. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xie F, Wu D, Huang SF, Cao JG, Li HN, He

L, Liu MQ, Li LF and Chen LX: The endoplasmic reticulum

stress-autophagy pathway is involved in apelin-13-induced

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

38:1589–1600. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Huang YL, Zhao F, Luo CC, Zhang X, Si Y,

Sun Z, Zhang L, Li QZ and Gao XJ: SOCS3-mediated blockade reveals

major contribution of JAK2/STAT5 signaling pathway to lactation and

proliferation of dairy cow mammary epithelial cells in vitro.

Molecules. 18:12987–13002. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Priya LB, Baskaran R, Huang CY and Padma

VV: Neferine ameliorates cardiomyoblast apoptosis induced by

doxorubicin: Possible role in modulating NADPH oxidase/ROS-mediated

NFkB redox signaling cascade. Sci Rep. 7:122832017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gao J, Chen T, Zhao D, Zheng J and Liu Z:

Ginkgolide B Exerts Cardioprotective properties against

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by regulating reactive oxygen

species, Akt and calcium signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo.

PLoS One. 11:e01682192016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yu Q, Li Q, Na R, Li X, Liu B, Meng L,

Liutong H, Fang W, Zhu N and Zheng X: Impact of repeated

intravenous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells infusion on

myocardial collagen network remodeling in a rat model of

doxorubicin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem.

387:279–285. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bakhtiari E, Hosseini A and Mousavi SH:

Protective effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa against serum/glucose

deprivation-induced PC12 cells injury. Avicenna J Phytomed.

5:231–237. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Huang CY, Chen JY, Kuo CH, Pai PY, Ho TJ,

Chen TS, Tsai FJ, Padma VV, Kuo WW, Huang CY, et al: Mitochondrial

ROS-induced ERK1/2 activation and HSF2-mediated AT1 R

upregulation are required for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J

Cell Physiol. 233:463–475. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ibrahim MA, Ashour OM, Ibrahim YF,

El-Bitar HI, Gomaa W and Abdel-Rahim SR: Angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibition and angiotensin AT(1)-receptor antagonism equally

improve doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

Pharmacol Res. 60:373–381. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Khosravi M, Poursaleh A, Ghasempour G,

Farhad S and Najafi M: The effects of oxidative stress on the

development of atherosclerosis. Biol Chem. 400:711–732. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wu J, Saleh MA, Kirabo A, Itani HA,

Montaniel KR, Xiao L, Chen W, Mernaugh RL, Cai H, Bernstein KE, et

al: Immune activation caused by vascular oxidation promotes

fibrosis and hypertension. J Clin Invest. 126:50–67. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|