Introduction

The past and present

The urinary bladder is an elastic reservoir that is

responsible for the low pressure storage of urine. A continent,

pain free and healthy bladder is crucial for the preservation of a

good quality of life. Numerous conditions disturb the anatomy and

physiology of the urinary bladder, leading to insufficient and

restricted evacuation of urine (1).

Bladder cancer (BC) is the sixth most common cause

of cancer-associated morbidity in the western world: In the UK in

2010, there were 10,300 new cases, and 4,900 cases of BC-associated

mortality (2). It represents the most

common malignancy of the urinary tract, with a median survival rate

following metastasis that rarely surpasses 15 months (3). The vast majority (90%) of bladder

tumours are histologically classified as urothelial cell carcinoma,

these tumours are often further classified as being non-muscle

invasive BC (NMIBC) or muscle invasive BC (MIBC) (4). On initial presentation, 30% of patients

are diagnosed with an MIBC tumour. From the remainder of patients

that had been diagnosed with an NMIBC tumour at presentation, 30%

go on to develop an MIBC during follow-up (5). With the highest susceptibility of

recurrence and progression of any malignancy, patients with BC

require consistent surveillance and close follow-up during and,

more importantly, following therapy. With such high odds of

recurrence, BC has produced the most expensive management protocol

of any malignancy, costing the National Health Service ~£55.39

million in the UK per annum (6). The

gold standard treatment for organ-confined MIBC is radical

cystectomy, with dissection of the pelvic lymph nodes. Regardless,

malignancy is not the sole bladder-associated pathology in which

cystectomy is indicated (7).

Bladder damage occurs in several additional

disorders within the genitourinary (GU) system, including

inflammatory conditions (interstitial cystitis/bladder pain

syndrome), urinary tract infections, nerve damage (neuropathic

bladder) and congenital disorders (spina bifida). In these cases,

the essential task is to re-establish the function of the urinary

bladder. Medical treatments are limited, and thus, surgical

intervention, particularly cystectomy, is often required (8–11).

Since the first BC-associated cystectomy in 1887,

the pursuit to identify the most appropriate replacement voiding

system has been largely problematic (12). At present, the most common method of

bladder replacement or repair involves the use of autologous

segments of gastrointestinal tissue, in order to restore bladder

storage and voiding capacity (13).

This is often achieved through ileal conduit urinary diversion,

orthotopic bladder substitution or continent cutaneous diversion

(Table I) (14,15).

| Table I.Surgical procedures used post

cystectomy. |

Table I.

Surgical procedures used post

cystectomy.

| Technique | Description |

|---|

| Ileal conduit

urinary diversion | Urine is drained

from the ureters to a loop of small bowel anastomosed to the

abdominal skin surface. It is then collected in an external

appliance. |

| Orthotopic bladder

substitution | This practice

imitates the typical role of the urinary bladder through using a

section of bowel to reconstruct the bladder. |

| Continent cutaneous

diversion | This method uses

the ileocaecal valve which may aid the regulation of urination.

This procedure utilises the bowel, which is deployed to mimic the

urinary bladder. The ureters are attached to the pouch. The pouch

is then brought to the skin as a stoma. |

|

Ureterosigmoidostomy | Possibly the oldest

procedure, here the ureters are attached to the large bowel and

urine exits this way. The anal sphincter provides continence. |

Since the original application of a free tissue

graft in 1917, in which canine bladders were augmented with fascia,

various additional materials have been utilized as free grafts

(16). The ileum, however, is the

most frequently utilized segment in bladder augmentation, due to

its notably simple mobilization, extensive mesentery and

copiousness; features that are particularly appropriate for urinary

tract substitution (17). Although

the use of gastrointestinal segments in bladder reconstruction was

first proposed almost 150 years ago, it remains the gold standard

due to the absence of a superior alternative. This was demonstrated

by Stein et al (18), who

observed excellent long-term survival rates in patients undergoing

radical cystectomy. Whilst radical extirpation of the bladder is

frequently successful, from an oncological perspective, substantial

morbidity is associated with enteric interposition within the GU

tract (Table II) (19–22).

Surgical intervention itself requires procedures on the urinary and

gastrointestinal tracts which are associated with complication

rates of ≤66%. Considering that the vast majority of patients that

require cystectomy and consequent bladder substitution are elderly

and suffer from other co-morbidities, in particular renal

impairment, urologists find themselves fighting an uphill battle in

surgical management post-cystectomy (16).

| Table II.Complications of current bladder

augmentation procedures through the use of gastrointestinal tissue

in the urinary tract. |

Table II.

Complications of current bladder

augmentation procedures through the use of gastrointestinal tissue

in the urinary tract.

| Complication | Description |

|---|

| Electrolyte

disturbances | Hyperchloreamic,

hypokalaemic metabolic acidosis is the most common complication. A

number of these patients will be required to take life long oral

Sodium bicarbonate as a result. |

| Vitamin

deficiency | Loss of segments of

bowel or stomach can impair vitamin B12/ bile salt/fat/fat soluble

vitamin absorption. Vitamin B12 deficiency can manifest as

peripheral neuropathy. |

| Drug

metabolism | Drugs can be

reabsorbed by the intestinal segments that have been incorporated

into the urinary tract, causing toxicity. Methotrexate, phenytoin

and lithium in particular result in therapeutic changes. Dose

adaptation and close surveillance is often required. |

| Hepatic

metabolism | The intestinal

segments that are used for diversion will drain into the portal

circulation and consequently, into the liver. This abnormal portal

system communication can lead to ammonia toxicity, manifesting as

ammoniagenic encephalopathy. |

| Bone disease | This is generally a

long term complication of diversion which has been demonstrated in

adults with osteomalacia and children with rickets. The

pathological process is complex, but it has been attributed to

chronic acidosis. |

| Cancer | Tumours have been

reported close to the anastomotic sites and include transitional

cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, sarcoma and adenomatous

polyps. |

| Surgical | These are numerous

and can manifest early or late. The most common complications are

stomal, including stomal bleeds, parastomal hernias and stomal

stenosis. |

Certain bladder pathologies, in particular

metastatic BC, are managed medically prior to considering radical

cystectomy. This method of organ preservation involves aggressive

treatment through surgery and radiotherapy, often with neo-adjuvant

chemotherapy as the treatment of choice (23). Currently, only multidrug

platinum-based chemotherapeutic regimens have been successful

(24,25), whereas monotherapy treatments have

failed (26,27). The methotrexate, vinblastine,

adriamycin and cisplatin (MVAC) and gemcitabine and cisplatin

(gem-cis) regimens have been the most commonly used

chemotherapeutic treatment regimens. However, the clinical efficacy

of cisplatin-based therapy in BC is currently restricted by the

rapid development of drug resistance in the majority of patients,

frequently leading to therapeutic failure (28). This was demonstrated in a previous

study in which response rates from BC patients receiving

chemotherapeutic drug intervention in phase II trials varied

between 20 and 60%, with the majority of survival rate advantage in

the randomised control trial setting (29,30). This

has resulted in the ever apparent requirement for bladder

reconstruction.

The future

The absence of autologous tissue with parallel

properties to the native bladder has directed numerous studies to

develop alternative methods of bladder substitution, avoiding the

use of bowel tissue altogether. The theory of substituting the

native bladder with a synthetic prosthesis has always been an

attractive prospect in the development of cutting edge technology.

Thus, tissue engineering, cell and stem cell biology, material

science and regenerative medicine are at the forefront of medical

research (31).

The fields of tissue engineering and regenerative

medicine have witnessed substantial progression over the previous

two decades. Various studies have investigated the possibility of

regenerating multilayer urothelium, which led to the first clinical

trial in 2006, in which Atala et al (32) investigated tissue engineered bladders

created from cell seeded grafts. The potential of such novel

findings has underlined the requirement for further advances in

tissue engineering and material science in order to define the

properties required for the ultimate reconstructive material and

method of implantation.

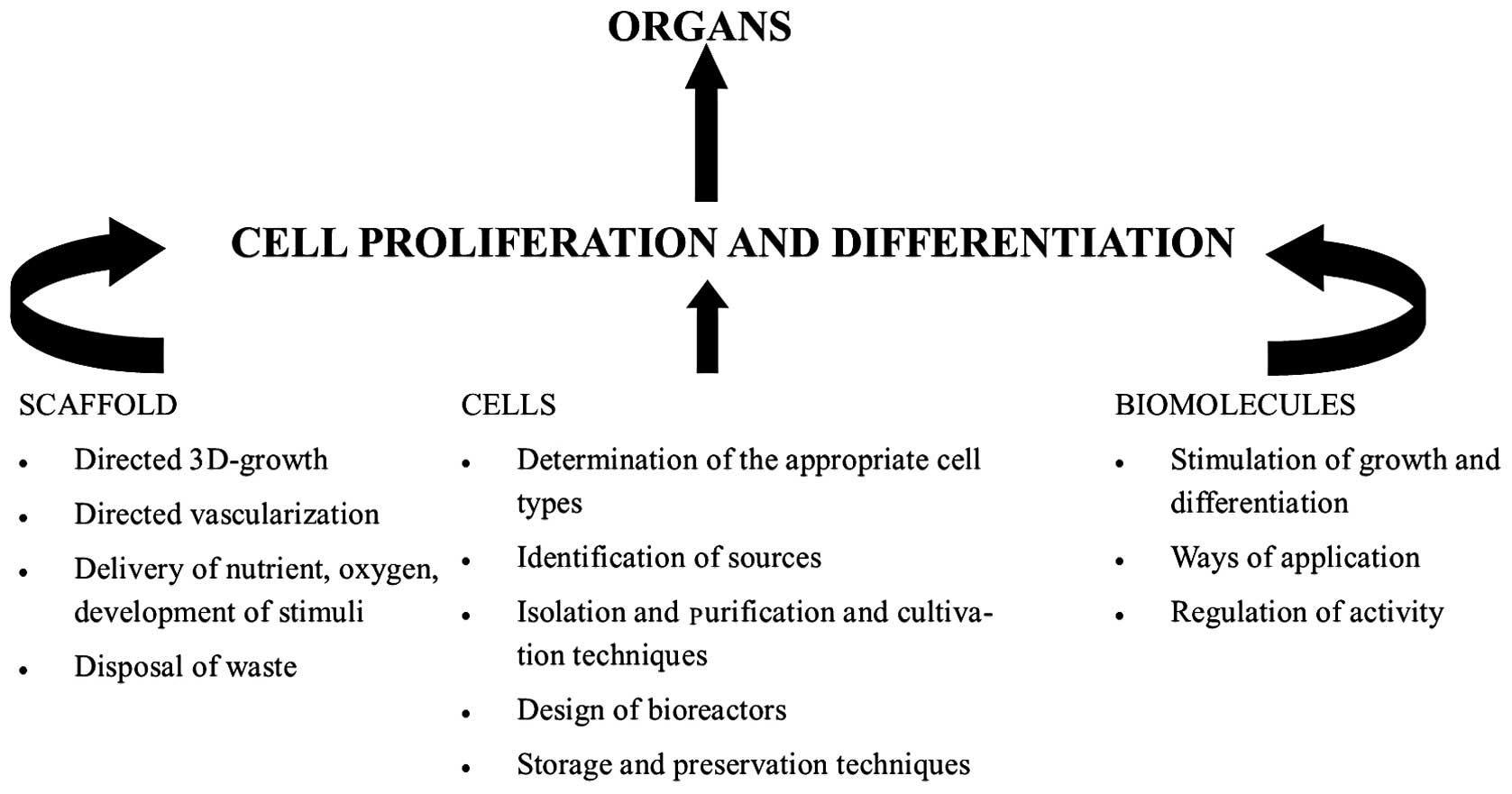

Tissue engineering is the mainstay of regenerative

medicine. It employs the disciplines of cell biology,

transplantation, material science and biomedical engineering,

towards identifying alternatives that can re-establish and preserve

the regular function of damaged tissues and organs (Fig. 1) (33).

Although the human body is outstanding in its ability to repair

damaged tissue, these reparative processes are frequently

restricted to the development of scar tissue. This often proves

detrimental in the function of the bladder (34). The ideal artificial bladder should

possess properties similar to that of the native urinary bladder.

It should possess the ability to store urine at low pressure in a

watertight structure, similar to a mechanical reservoir, and permit

voluntary voiding with minimal reflux. This structure should also

be constructed from inert material and cause minimal complications

in the patient so that long-term renal function is not compromised

(35). Previously published animal

studies have demonstrated promising results in the field of

regenerative medicine, and it represents a possible solution for

the treatment of a number of urological conditions in the future

(31).

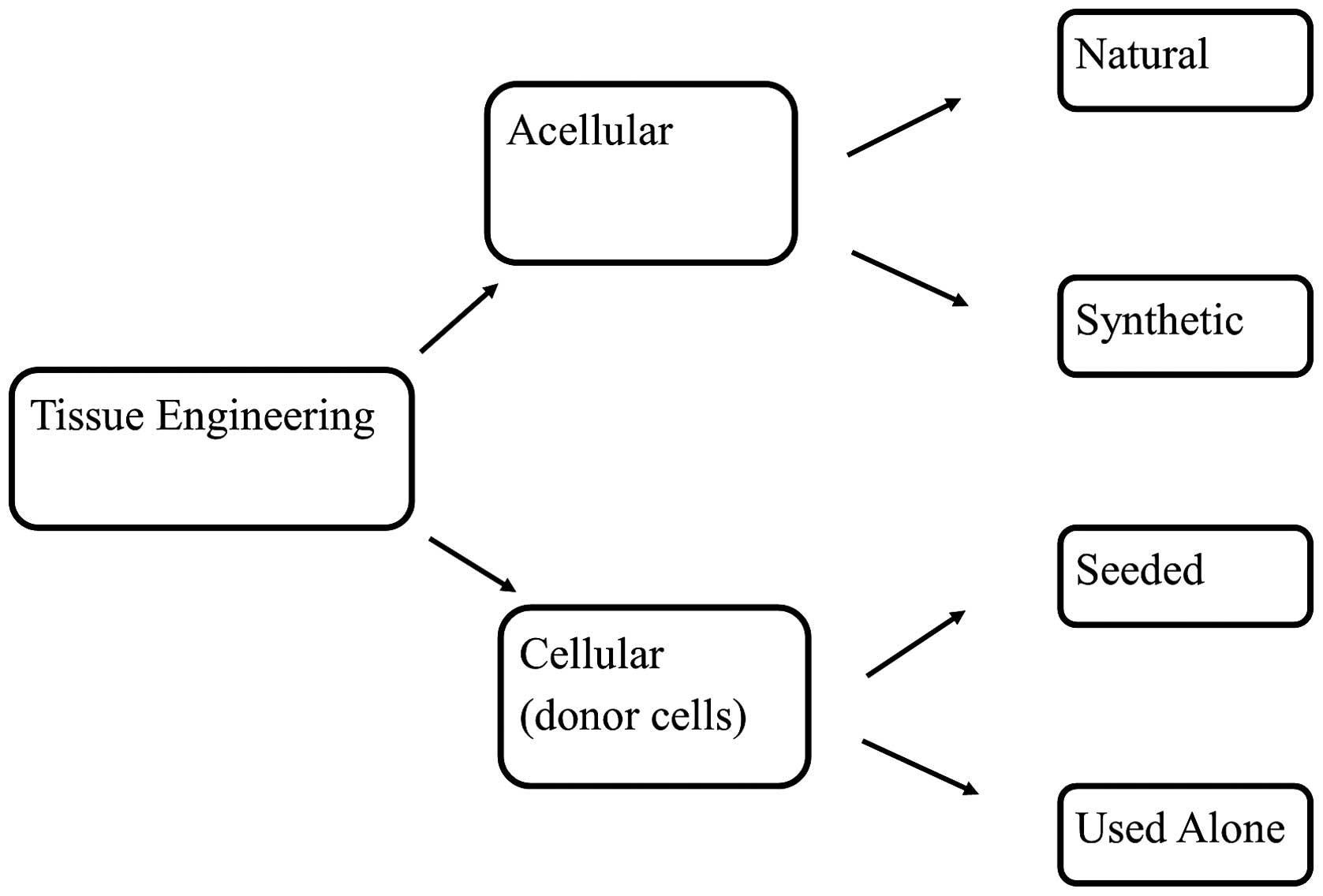

Tissue engineering strategies vary, and currently,

studies are being orientated in two directions: Firstly, to

identify the most appropriate type of stem cell for regeneration

and to proficiently incorporate it into bladder cells; secondly, to

determine the most appropriate material and technique of embedding

these cells using tissue engineered grafts (Fig. 2) (36,37). The

selected grafts must exhibit all the qualities of the native

tissue, acting ultimately as microenvironments for the implanted

cells to prosper (38).

Biomaterials in bladder regeneration

There are distinct benefits to using biocompatible

material in regenerative medicine for the purpose of cell delivery

vehicles, and for bearing the physical maintenance required for

tissue replacement (39). Scaffolds

are constructs that are designed to direct tissue development and

the growth of cells during the process of healing (40). Bladder replacements should therefore

provide provisional mechanical support, adequate to endure forces

exerted from neighbouring structures, whilst maintaining a

potential zone for tissue development. Biomaterials used for

bladder replacements should possess the ability to be easily

manipulated into a hollow, spherical configuration. Furthermore,

the biomaterials should possess the ability to biodegrade for

complete tissue development, without causing inflammation.

Autologous tissue has been experimented on for bladder repair since

the early 1980s (41). The use of

omentum, pericardium, stomach and skin has been attempted with

limited success (42–45). It was the lack of watertight

properties that led to the failure of these materials. It is clear

that the anatomical and physiological properties of the urinary

bladder are not easily substituted.

Biomaterials can be divided into 3 main categories:

i) Naturally derived matrices, including collagen; ii) acellular

tissue matrices, including bladder submucosa; and iii) synthetic

matrices, including poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) (46).

Naturally derived matrices

Collagen is considered to be the most ubiquitous

protein in the human body, and it is often used alongside alginate

as a natural matrix. It is useful in tissue engineering, as it

possesses the ability to be easily manipulated and does not provoke

an immune response (47). Through the

use of innovative inkjet technology, it has been possible to use

bio-printing to create a naturally derived 3D construct, with a

precise arrangement of growth factors and other cellular

components, into a patient-specific scaffold (48).

Acellular tissue matrices

Decellularised matrices are the most commonly used

naturally derived urological matrices. They are usually harvested

from autologous, allogenic or xenogenic tissue (49,50).

Chemical or mechanical processing decellularises the matrix,

removing all cellular components and leaving a natural platform for

tissue development (51). The most

common origin of decellularised matrices is tissue harvested from

the bladder or small intestinal mucosa (52). Once implanted, the matrices eventually

degrade and are ultimately replaced by an extracellular matrix. The

matrices provide cells with a structural support that can dictate

the tissue structure. Bladder acellular matrix may be the most

extensively used scaffold in tissue engineering. It has been

demonstrated that the cells have the ability to induce the ingrowth

of urothelium, smooth muscle, endothelium and nerve cells (53). Perhaps the greatest advantage of the

use of acellular matrices is the ability to provide a method of

neovascularisation following graft insertion, promoting graft

survival. Kikuno et al (54)

demonstrated that nerve growth factor and vascular endothelial

growth factor enhanced bladder acellular matrix grafting in

neurogenic rat bladders through increased angiogenesis and

neurogenesis (55).

However, in general, these materials possess various

drawbacks depending on their graft origin. Autologous materials

have proven difficult to reproduce as a result of increased patient

morbidity associated with the graft harvest (56). The increased cost in allograft and

xenograft material production, in addition to the risk of disease

transmission and varied mechanical strength, is crucial in their

limited clinical application (56,57).

Furthermore, the use of natural decellularised matrices requires

tissue that exhibits no principal pathological change, and is

therefore unfeasible in certain patients (58,59). In

addition, the aggressive decellularisation and sterilisation

protocols used can denature proteins in the extracellular matrix,

damaging the physiological environment (60).

Synthetic matrices

The use of synthetic material in patients in which

the native bladder has undergone pathological change, such as BC,

is hypothesised to be the ideal solution. The most commonly used

materials in experimental studies and clinical trials are Teflon,

silicon and collagen matrices (61).

However, cell and tissue incompatibilities appear to be the major

restrictions of these materials, leading to the development of

other synthetic polymers, such as PLGA (62–65). These

materials were designed specifically to possess adequate structural

and biological properties, which can be manipulated for optimal

cell proliferation and differentiation (66). In addition, these scaffolds are safe,

possess controlled properties of degradation rate and strength, are

readily available and possess the ability to carry vital growth

factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, for

neovascularisation (67–69). Indeed, the most attractive property of

PLGA compared with older polymers, such as Teflon, is its

resorbable biodegradability. This eliminates the disadvantages of

infection, calcification and unfavourable connective tissue

responses observed in older polymers (70). When using polymers, tissue recognition

is difficult, and often requires immunosuppressive therapy.

However, it has now been demonstrated that novel biological

factors, including adhesive proteins such as collagen and

fibronectin and growth factors such as basic fibroblast growth

factor, epidermal growth factor and insulin, are able to enhance

cell recognition (71,72).

The failure of certain materials in clinical cases

has been extensively reported, including plastic moulds (73,74),

gelatin sponges (75,76), Japanese paper produced from the rice

paper plant (Tetrapanax papyrifer) (77,78) and

bovine pericardium (79,80).

Nanotechnology, which arose in the last decade of

the 20th century, has been used in the formation of matrices that

can be composed of natural and synthetic materials. The use of

nanotechnology permits the development of a graft that can be

manipulated to produce characteristics with definitive properties

in order to promote optimal cell proliferation and tissue

differentiation (53). A previous

study investigated the effect of surface roughness on the

interaction with matrix proteins (81). Vitronectin absorbance improved by 20%

with the addition of nanotechnology-induced surface roughness in

the synthetic materials compared with the nanosmooth surface.

Similarly, enhanced adhesion and proliferation of urothelial cells

has been demonstrated with increased synthetic surface roughness

(82).

The use of unseeded and cell-seeded matrices

in bladder regeneration

Although there have been studies illustrating the

use of unseeded matrices in bladder tissue engineering, the results

of these studies have been inconclusive. The normal regeneration of

the urothelium layer has been demonstrated in unseeded grafts used

for cystoplasty, however, the muscular layer did not develop

(83). By contrast, the cell-seeded

approach has produced more positive and consistent results in

bladder reconstruction, and has been the most extensively

investigated strategy in reconstruction. This approach involves

seeding of a scaffold with autologous patient-derived cells, which

is then transplanted back into the patient to accomplish

regeneration (32).

In a study conducted on beagle dogs following

subtotal cystectomy, polyglycolic acid acellular matrices were

seeded with urothelium and smooth muscle cells. These dogs

demonstrated a 95% increase in pre-operative bladder capacity

compared with dogs treated with an unseeded matrix, indicating a

46% increase in pre-operative bladder capacity (84).

The study by Atala et al (32) was crucial for the first

laboratory-created organ to be transplanted into the human body.

The authors demonstrated an increase in bladder compliance and

capacity, and a reduction in end filling pressure in 7 patients

with neurogenic bladder (myelo meningocele). These patients

underwent cystoplasty created from autologous cells seeded on

collagen-polyglycolic acid scaffolds. This small clinical study

established the possibility of using tissue-engineered substitutes

for organ replacements in humans, circumventing the complications

of intestinal substitutes (32).

Stem cells in bladder regeneration

Historically, tissue engineering has depended on

autologous cells from the host organ. However, physiologically

normal tissue may not always be available for harvest to elaborate

a regenerative cystoplasty, this has led to the use of stem cells

as an alternative to restore urinary bladder function. The aim of

using stem cells as a therapeutic option is to achieve adequate

differentiation into urothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, so

that the normal histological structure is maintained for use as a

potential resource for cell-based therapy in urology (85).

Embryonic stem cells are a group of pluripotent stem

cells and exhibit two valuable attributes, including the capability

to undergo self-renewal and the capability to differentiate into

numerous specialised cell types. The in vivo benefits of

these have been demonstrated previously (86,87),

although the exact culture conditions which would enable controlled

differentiation are yet to be identified. However, their potential

for tumorigenicity, the prospect of immune rejection and the

ethical dilemmas associated with embryonic stem cells have limited

their clinical application (85).

Adult stem cells are the most extensively

investigated cell types in stem cell biology, regardless,

progression has been slow. Despite this, study of adult stem cells

is ongoing due to their extensive potential to be applied as

therapies in a vast array of disorders. The most promising source

of adult stem cells is adult bone marrow. The use of autologous

adult stem cells avoids the obstacles associated with an immune

response (88,89), which is useful for autologous and

tissue-specific regenerative therapies. Within the past two

decades, stem cells have been identified throughout the tissues of

the body, not just the bone marrow (90). It has been indicated that stem cells

may function as primary repair entities for the particular organ in

which they reside. These tissue-specific progenitors are now the

subject of numerous different areas of research (88).

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are derived from the

bone marrow stroma. MSCs have been demonstrated to differentiate

in vitro into a variety of tissue types, including smooth

muscle, urothelium and endothelial cells. It is for this reason

that bone marrow-derived MSCs are an attractive candidate for

bladder tissue regeneration (91).

Chung et al (92) reported

positive results in healthy rat bladders following the introduction

of porcine small intestinal submucosa seeded with MSCs from rat

bone marrow. These rats exhibited normal urinary bladder

architecture, and histological analysis demonstrated

well-differentiated urothelial and smooth muscle cells compared

with control experiments using unseeded intestinal submucosa

(92).

Amniotic fluid-derived stem (AFS) cells,

adipose-derived stem cells, and stem cells isolated from hair have

all demonstrated the capability of differentiating into different

urinary bladder cells in vitro (52,93,94). AFS

cells were initially isolated for therapeutic use in 2007 and

represent a minor subset of cells originating from the placenta and

amniotic fluid (95). AFS cells have

been demonstrated to expand extensively, doubling every 36 h

(96). They have the advantage over

embryonic stem cells in that they do not form tumours in

vivo (95). AFS cells possess a

differentiation potential between that of adult stem cells and

embryonic stem cells and can be obtained from routine clinical

amniocentesis, prenatal chorionic villus biopsies and placental

biopsies performed after birth (95).

Since their identification, these cells have been demonstrated to

differentiate into functioning cell types of numerous different

organs and to prevent bladder hypertrophy in cryo-injured mouse

bladders in vitro via the regulation of post-injury bladder

remodelling (97). AFS cells possess

a wide range of potential applications in the field of regenerative

medicine, and may in theory supply the vast majority of the UK with

suitable genetic matches for transplantation (98–100).

Stem cells are currently employed in tissue

engineering using two main methods, including implantation of the

stem cells in vivo without pre-differentiation and induction

of stem cell differentiation towards the bladder in vitro

followed by its implantation in vivo (101). The first method is often employed

when a section of the bladder requires reconstruction, in

comparison with the second method that is used when de novo

whole bladder reconstruction is required.

Innervation is vital in bladder reconstruction. The

autonomic nervous system controls the function of the bladder, thus

a poorly functioning neuronal network can lead to significant

bladder dysfunction (102). It has

been indicated that seeding Schwann cells and neurotrophic factors

may encourage nerve innervation of the urinary bladder (103).

Several bladder malformations exist, which are often

identified prenatally with sonography. The future prenatal

management of patients with bladder disease has emerged as a

notable possibility (104). The

potential to have readily available urological tissue at birth for

a one-stage reconstruction following prenatal ultrasound-guided

bladder biopsy is of note as this would present a significant

advancement for the treatment of congential urinary tract

abnormalities as cells could be harvested and grown in

transplantable tissue during gestation. This has been successfully

demonstrated in foetal lambs (105).

Chondrocytes obtained from hyaline and elastic cartilage were

harvested from fetal lambs, expanded in vitro and seeded

onto biodegradable scaffolds. The scaffolds were then implanted as

replacement tracheal tissue in fetal lambs. Strucural support and

patency of the tissue engineered cartilage was maintained and all

lambs that were allowed to reach term were able to breathe

spontaneously. Thus, this may be useful for in utero repair

of congenital tracheal abnormalities, such as tracheal atresia and

agenesis (106,107).

Conclusion and perspectives

Existing data indicates a forthcoming role of tissue

engineering disciplines in the management of urological diseases.

With the extensive advancements within the field in previous years,

the future of urology appears positive. However, the current

knowledge of bladder reconstruction is insufficient in order to use

it as a clinical standard in mainstream urological practice.

Additional in vitro studies are required to make this

possible. The most significant obstacle in material science is the

equilibrium between the creation of biomaterials that are patient-

and disease-specific and fit for purpose and a cost-effective

manufacturing process. The primary objective in the field of cell

biology and transplantation is not solely to control stem cell

differentiation in vivo but also to be able to manage their

growth following transplantation. The most significant aspect of

cell type selection is the degree of regenerative potential; the

more regenerative the cell is, the more likely it is to survive

when implanted in vivo. The survival of artificial tissue

following transplantation has been a significant obstacle thus far

in current tissue engineering strategies. Other factors other than

cell type selection are also important, however these factors often

depend on the ability for the tissue to maintain initial growth and

survive. Thus, as the tissue grows a healthy self-sustained process

of self repair is required, however, this will vary depending on

the cell type used.

References

|

1

|

Walters MD and Weber AM: Anatomy of the

lower urinary tract, rectum and pelvic floor. In: Urogynecology and

Pelvic Reconstructive SurgeryWalters MD and Karram MM: 2nd. Mosby,

St. Louis, MO: pp. 3–13. 2000

|

|

2

|

Cancer Research UK, . Bladder Cancer

Survival Statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/?=5441Accessed.

April 10–2015

|

|

3

|

BMJ, . Best practise: Epidemiology.

http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/980/basics/epidemiology.htmlAccessed.

April 11–2015

|

|

4

|

Cancer Research UK, . Types of bladder

cancer. http://cancerhelp.cancerresearchuk.org/type/bladder-cancer/about/types-of-bladder-cancer#spreadAccessed.

April 11–2015

|

|

5

|

Witjes JA, Compérat E, Cowan NC, et al:

EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer:

Summary of the 2013 guidelines. Eur Urol. 65:778–792. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sievert KD, Amend B, Nagele U, Schilling

D, Bedke J, Horstmann M, Hennenlotter J, Kruck S and Stenzl A:

Economic aspects of bladder cancer: What are the benefits and

costs? World J Urol. 27:295–300. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee RK, Abol-Enein H, Artibani W, et al:

Urinary diversion after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer:

Options, patient selection, and outcomes. BJU Int. 113:11–23. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hautmann S, Felix-Chun KH, Currlin E, et

al: Cystectomy for indications other than bladder cancer. Urologe

A. 43:172–177. 2004.(In German). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Evans B, Montie JE and Gilbert SM:

Incontinent or continent urinary diversion: How to make the right

choice. Curr Opin Urol. 20:421–425. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Westney OL: The neurogenic bladder and

incontinent urinary diversion. Urol Clin North Am. 37:581–592.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Andersen AV, Granlund P, Schultz A,

Talseth T, Hedlund H and Frich L: Long-term experience with

surgical treatment of selected patients with bladder pain

syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 46:284–289.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Poole-Wilson DS and Barnard RJ: Total

cystectomy for bladder tumours. Br J Urol. 43:16–24. 1971.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Cody JD, Nabi G, Dublin N, McClinton S,

Neal DE, Pickard R and Yong SM: Urinary diversion and bladder

reconstruction/replacement using intestinal segments for

intractable incontinence or following cystectomy. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 15:CD0033062012.

|

|

14

|

Parekh DJ and Donat SM: Urinary diversion:

Options, patient selection, and outcomes. Semin Oncol. 34:98–109.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Basic DT, Hadzi-Djokic J and Ignjatovic I:

The history of urinary diversion. Acta Chir Iugosl. 54:9–17. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Neuhof H: Facial transplantation into

visceral defects: An experimental and clinical study. Surg Gynecol

Obstet. 25:3831917.

|

|

17

|

Moon A, Vasdev N and Thorpe AC: Continent

urinary diversion. Indian J Urol. 29:303–309. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, et al:

Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer:

Long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 19:666–675.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mills RD and Studer UE: Metabolic

consequences of continent urinary diversion. J Urol. 161:1057–1066.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Shimko MS, Tollefson MK, Umbreit EC,

Farmer SA, Blute ML and Frank I: Long-term complications of conduit

urinary diversion. J Urol. 185:562–567. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hautmann RE: Urinary diversion: Ileal

conduit to neobladder. J Urol. 169:834–842. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hyndman ME, Kaye D, Field NC, et al: The

use of regenerative medicine in the management of invasive bladder

cancer. Adv Urol. 2012:6536522012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hussain SA, Moffitt DD, Glaholm JG, Peake

D, Wallace DM and James ND: A phase I-II study of synchronous

chemoradiotherapy for poor prognosis locally advanced bladder

cancer. Ann Oncol. 12:929–935. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Harker WG, Meyers FJ, Freiha FS, Palmer

JM, Shortliffe LD, Hannigan JF, McWhirter KM and Torti FM:

Cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine (CMV): An effective

chemotherapy regimen for metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of

the urinary tract. A Northern California Oncology Group study. J

Clin Oncol. 3:1463–1470. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Sternberg CN, Yagoda A, Scher HI, et al:

Preliminary results of M-VAC (methotrexate, vinblastine,

doxorubicin and cisplatin) for transitional cell carcinoma of the

urothelium. J Urol. 133:403–407. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Saxman SB, Propert KJ, Einhorn LH,

Crawford ED, Tannock I, Raghavan D, Loehrer PJ Sr and Trump D:

Long-term follow up of a phase III intergroup study of cisplatin

alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and

doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A

cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 15:2564–2569.

1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Waxman J and Barton C: Carboplatin-based

chemotherapy for bladder cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 19(Suppl C):

S21–S25. 1993.

|

|

28

|

Stewart DJ: Mechanisms of resistance to

cisplatin and carboplatin. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 63:12–31. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hussain SA, Stocken DD, Riley P, et al: A

phase I/II study of gemcitabine and fractionated cisplatin in an

outpatient setting using a 21-day schedule in patients with

advanced and metastatic bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 91:844–849.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

James ND, Hussain SA, Hall E, et al:

BC2001 Investigators: Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in

muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 366:1477–1488. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Atala A: Tissue engineering for bladder

substitution. World J Urol. 18:364–370. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Atala A, Bauer SB, Soker S, Yoo JJ and

Retik AB: Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients

needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 367:1241–1246. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Aboushwareb T, McKenzie P, Wezel F,

Southgate J and Badlani G: Is tissue engineering and biomaterials

the future for lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD)/pelvic organ

prolapse (POP)? Neurourol Urodyn. 30:775–782. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Baskin LS, Sutherland RS, Thomson AA,

Nguyen HT, Morgan DM, Hayward SW, Hom YK, DiSandro M and Cunha GR:

Growth factors in bladder wound healing. J Urol. 157:2388–2395.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Korossis S, Bolland F, Ingham E, Fisher J,

Kearney J and Southgate J: Review: Tissue engineering of the

urinary bladder: considering structure-function relationships and

the role of mechanotransduction. Tissue Eng. 12:635–644. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Petrovic V, Stankovic J and Stefanovic V:

Tissue engineering of the urinary bladder: Current concepts and

future perspectives. ScientificWorldJournal. 11:1479–1488. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Shokeir AA, Harraz AM and El-Din AB:

Tissue engineering and stem cells: Basic principles and

applications in urology. Int J Urol. 17:964–973. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wood D and Southgate J: Current status of

tissue engineering in urology. Curr Opin Urol. 18:564–569. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Furth ME, Atala A and Van Dyke ME: Smart

biomaterials design for tissue engineering and regenerative

medicine. Biomaterials. 28:5068–5073. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chan BP and Leong KW: Scaffolding in

tissue engineering: General approaches and tissue-specific

considerations. Eur Spine J. 17(Suppl 4): S467–S479. 2008.

|

|

41

|

Davis NF, Callanan A, McGuire BB, Mooney

R, Flood HD and McGloughlin TM: Porcine extracellular matrix

scaffolds in reconstructive urology: An ex vivo comparative study

of their biomechanical properties. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater.

4:375–382. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Goldstein MB, Dearden LC and Gualtieri V:

Regeneration of subtotally cystectomized bladder patched with

omentum: An experimental study in rabbits. J Urol. 97:664–668.

1967.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Andretto R, Gonzales J, Guidugli Netro J,

de Miranda JF and Antunes AM: Experimental cystoplasty in dogs

using preserved equine pericardium. AMB Rev Assoc Med Bras.

27:153–154. 1981.(In Portuguese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Nguyen DH and Mitchell ME: Gastric bladder

reconstruction. Urol Clin North Am. 18:649–657. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Draper JW and Stark RB: End results in the

replacement of mucous membrane of the urinary bladder with

thick-split grafts of skin. Surgery. 39:434–440. 1956.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Atala A: Tissue engineering of human

bladder. Br Med Bull. 97:81–104. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Dahms SE, Piechota HJ, Dahiya R, Lue TF

and Tanagho EA: Composition and biomechanical properties of the

bladder acellular matrix graft: Comparative analysis in rat, pig

and human. Br J Urol. 82:411–419. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Mahfouz W, Elsalmy S, Corcos J and Fayed

AS: Fundamentals of bladder tissue engineering. Afr J Urol.

19:51–57. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Yoo JJ, Meng J, Oberpenning F and Atala A:

Bladder augmentation using allogenic bladder submucosa seeded with

cells. Urology. 51:221–225. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Sutherland RS, Baskin LS, Hayward SW and

Cunha GR: Regeneration of bladder urothelium, smooth muscle, blood

vessels and nerves into an acellular tissue matrix. J Urol.

156:571–577. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Crapo PM, Gilbert TW and Badylak SF: An

overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes.

Biomaterials. 32:3233–3243. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Langer R and Vacanti JP: Tissue

engineering. Science. 260:920–926. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Brehmer B, Rohrmann D, Becker C, Rau G and

Jakse G: Different types of scaffolds for reconstruction of the

urinary tract by tissue engineering. Urol Int. 78:23–29. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kikuno N, Kawamoto K, Hirata H, et al:

Nerve growth factor combined with vascular endothelial growth

factor enhances regeneration of bladder acellular matrix graft in

spinal cord injury-induced neurogenic rat bladder. BJU Int.

103:1424–1428. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Atala A: Recent developments in tissue

engineering and regenerative medicine. Curr Opin Pediatr.

18:167–171. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Orabi H, Bouhout S, Morissette A, Rousseau

A, Chabaud S and Bolduc S: Tissue engineering of urinary bladder

and urethra: Advances from bench to patients.

ScientificWorldJournal. 2013:1545642013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Brown AL, Farhat W, Merguerian PA, Wilson

GJ, Khoury AE and Woodhouse KA: 22 week assessment of bladder

acellular matrix as a bladder augmentation material in a porcine

model. Biomaterials. 23:2179–2190. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Subramaniam R, Hinley J, Stahlschmidt J

and Southgate J: Tissue engineering potential of urothelial cells

from diseased bladders. J Urol. 186:2014–2020. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Chung SY: Bladder tissue-engineering: a

new practical solution? Lancet. 367:1215–1216. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Atala A: Autologous cell transplantation

for urologic reconstruction. J Urol. 159:2–3. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Matoka DJ and Cheng EY: Tissue engineering

in urology. Can Urol Assoc J. 3:403–408. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Bogash M, Kohler FP, Scott RH and Murphy

JJ: Replacement of the urinary bladder by a plastic reservoir with

mechanical valves. Surg Forum. 10:900–903. 1960.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Bona AV and De Gresti A: Partial

substitution of the bladder wall with teflon tissue. (Preliminary

and experimental note on the impermeability and tolerance of the

prosthesis). Minerva Urol. 18:43–47. 1966.(In Italian). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kelâmi A, Dustmann HO, Lüdtke-Handjery A,

Cárcamo V and Herlld G: Experimental investigations of bladder

regeneration using teflon-felt as a bladder wall substitute. J

Urol. 104:693–698. 1970.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Rohrmann D, Albrecht D, Hannappel J,

Gerlach R, Schwarzkopp G and Lutzeyer W: Alloplastic replacement of

the urinary bladder. J Urol. 156:2094–2097. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Baker SC, Rohman G, Southgate J and

Cameron NR: The relationship between the mechanical properties and

cell behaviour on PLGA and PCL scaffolds for bladder tissue

engineering. Biomaterials. 30:1321–1328. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Pattison MA, Wurster S, Webster TJ and

Haberstroh KM: Three dimensional, nano-structured PLGA scaffolds

for bladder tissue replacement applications. Biomaterials.

26:2491–2500. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Pariente JL, Kim BS and Atala A: In vitro

biocompatibility assessment of naturally derived and synthetic

biomaterials using normal human urothelial cells. J Biomed Mater

Res. 55:33–39. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Chen FM, Zhang M and Wu ZF: Toward

delivery of multiple growth factors in tissue engineering.

Biomaterials. 31:6279–6308. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Ulery BD, Nair LS and Laurencin CT:

Biomedical applications of biodegradable polymers. J Polym Sci B

Polym Phys. 49:832–864. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Harrington DA, Sharma AK, Erickson BA and

Cheng EY: Bladder tissue engineering through nanotechnology. World

J Urol. 26:315–322. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Elbert DL and Hubbell JA: Surface

treatments of polymers for biocompatibilityAnnual Review of

Materials Science. Vol 26. Annual Reviews. Palo Alto, CA: pp.

365–394. 1996

|

|

73

|

Bohne AW and Urwiller KL: Experience with

urinary bladder regeneration. J Urol. 77:725–732. 1957.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Portilla Sanchez R, Blanco FL, Santamarina

A, Casals Roa J, Mata J and Kaufman A: Vesical regeneration in the

human after total cystectomy and implantation of a plastic mould.

Br J Urol. 30:180–188. 1958. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Tsuji I, Kuroda K, Fujieda J, Shiraishi Y

and Kunishima K: Clinical experiences of bladder reconstruction

using preserved bladder and gelatin sponge bladder in the case of

bladder cancer. J Urol. 98:91–92. 1967.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Orikasa S and Tsuji I: Enlargement of

contracted bladder by use of gelatin sponge bladder. J Urol.

104:107–110. 1970.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Taguchi H, Ishizuka E and Saito K:

Cystoplasty by regeneration of the bladder. J Urol. 118:752–756.

1977.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Fujita K: The use of resin-sprayed thin

paper for urinary bladder regeneration. Invest Urol. 15:355–357.

1978.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Moon SJ, Kim DH, Jo JK, et al: Bladder

reconstruction using bovine pericardium in a case of enterovesical

fistula. Korean J Urol. 52:150–153. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Pokrywczynska M, Adamowicz J, Sharma AK

and Drewa T: Human urinary bladder regeneration through tissue

engineering - an analysis of 131 clinical cases. Exp Biol Med

(Maywood). 239:264–271. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Shakhssalim N, Dehghan MM, Moghadasali R,

Soltani MH, Shabani I and Soleimani M: Bladder tissue engineering

using biocompatible nanofibrous electrospun constructs: Feasibility

and safety investigation. Urol J. 9:410–419. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Chun YW, Khang D, Haberstroh KM and

Webster TJ: The role of polymer nanosurface roughness and submicron

pores for improving bladder urothelial cell density and inhibiting

calcium oxalate stone formation. Nanotechnology. 20:0851042009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Probst M, Dahiya R, Carrier S and Tanagho

EA: Reproduction of functional smooth muscle tissue and partial

bladder replacement. Br J Urol. 79:505–515. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Oberpenning F, Meng J, Yoo JJ and Atala A:

De novo reconstitution of a functional mammalian urinary bladder by

tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 17:149–155. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Aboushwareb T and Atala A: Stem cells in

urology. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 5:621–631. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lamba DA, Gust J and Reh TA:

Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell derived photoreceptors

restores some visual function in Crx-deficient mice. Cell Stem

Cell. 4:73–79. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Yang D, Zhang ZJ, Oldenburg M, Ayala M and

Zhang SC: Human embryonic stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons

reverse functional deficit in parkinsonian rats. Stem Cells.

26:55–63. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Ballas CB, Zielske SP and Gerson SL: Adult

bone marrow stem cells for cell and gene therapies: Implications

for greater use. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 38(S38): 20–28.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Gonzalez MA and Bernad A: Characteristics

of adult stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 741:103–120. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Spradling A, Drummond-Barbosa D and Kai T:

Stem cells find their niche. Nature. 414:98–104. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

da Silva Meirelles L, Chagastelles PC and

Nardi NB: Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal

organs and tissues. J Cell Sci. 119:2204–2213. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Chung SY, Krivorov NP, Rausei V, et al:

Bladder reconstitution with bone marrow derived stem cells seeded

on small intestinal submucosa improves morphological and molecular

composition. J Urol. 174:353–359. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al: Human

adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol

Cell. 13:4279–4295. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Drewa T: Using hair-follicle stem cells

for urinary bladder-wall regeneration. Regen Med. 3:939–944. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

de Coppi P, Bartsch G Jr..Siddiqui MM, et

al: Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for

therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 25:100–106. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Mosquera A, Fernández JL, Campos A,

Goyanes VJ, Ramiro-Díaz J and Gosálvez J: Simultaneous decrease of

telomere length and telomerase activity with ageing of human

amniotic fliuds cells. J Med Genet. 36:494–496. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

de Coppi P, Callegari A, Chiavegato A, et

al: Amniotic fluid and bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells

can be converted to smooth muscle cells in the cryo-injured rat

bladder and prevent compensatory hypertrophy of surviving smooth

muscle cells. J Urol. 177:369–376. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Perin L, Sedrakyan S, Giuliani S, et al:

Protective effect of human amniotic fluid stem cells in an

immunodeficient mouse model of acute tubular necrosis. PLoS One.

5:e93572010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Moorefield EC, McKee EE, Solchaga L,

Orlando G, Yoo JJ, Walker S, Furth ME and Bishop CE: Cloned, CD117

selected human amniotic fluid stem cells are capable of modulating

the immune response. PLoS One. 6:e265352011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Weber B, Emmert MY, Behr L, et al:

Prenatally engineered autologous amniotic fluid stem cell-based

heart valves in the fetal circulation. Biomaterials. 33:4031–4043.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Tian H, Bharadwaj S, Liu Y, Ma PX, Atala A

and Zhang Y: Differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells into bladder cells: Potential for urological tissue

engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 16:1769–1779. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Fowler CJ, Griffiths D and de Groat WC:

The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 9:453–466.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Adamowicz J, Drewa T, Tworkiewicz J,

Kloskowski T, Nowacki M and Pokrywczyńska M: Schwann cells - a new

hope in tissue engineered urinary bladder innervation A method of

cell isolation. Cent European J Urol. 64:87–89. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Hindryckx A and De Catte L: Prenatal

diagnosis of congenital renal and urinary tract malformations.

Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 3:165–174. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Koh CJ and Atala A: Tissue engineering,

stem cells, and cloning: Opportunities for regenerative medicine. J

Am Soc Nephrol. 15:1113–1125. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Fuchs JR, Terada S, Ochoa ER, Vacanti JP

and Fauza DO: Fetal tissue engineering: In utero tracheal

augmentation in an ovine model. J Pediatr Surg. 37:1000–1006. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Fuchs JR, Hannouche D, Terada S, Vacanti

JP and Fauza DO: Fetal tracheal augmentation with cartilage

engineered from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. J

Pediatr Surg. 38:984–987. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|