Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is one of the

most common malignant tumors, and the 5-year survival rate

following diagnosis is <15% (1).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is associated with the

growth and progression of cancer and an activation mutation in the

tyrosine kinase domain (exon 21 L858R point mutation or exon-19

deletion) has been identified as an oncogenic driver of NSCLC

(2). A study has shown that 30–40%

of Asian patients with NSCLC harbor EGFR mutations at the time of

diagnosis (3). Although it was

demonstrated that the overall response and disease control rates in

gefitinib- and erlotinib-treated groups (via targeting of EGFR)

were 76.9 vs. 74.4% and 90.1 vs. 86.8%, respectively (4), drug resistance is inevitable, and ~36%

of patients with NSCLC have EGFR T790M/L858R resistance mutations

(5). Although a second-generation

EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), afatinib, showed high

activity in an EGFR T790M/L858R driven xenotransplantation model,

it did not increase the objective response rate in patients with

NSCLC with drug-resistant mutations (6). Third-generation EGFR-TKIs, such as

CO1686 and AZD9291, are the only effective drugs for treating NSCLC

with the EGFR L858R/T790M mutation (7,8).

However, because the drug resistance molecular subtypes emerged

(such as acquisition of the EGFR C797S mutation or loss of the

T790M mutation), drug resistance is still inevitable after a period

of treatment (9). Additionally,

EGFR-TKIs may not be superior to chemotherapy in patients with

NSCLC with wild-type EGFR (10). A

study demonstrated that chemotherapy showed a superiority in terms

of PFS (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.35–2.52) and ORR (16.8 vs. 7.2%;

relative risk, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02–1.21) compared with EGFR-TKIs in

patients with NSCLC with wild-type EGFR (11). Chemotherapy remains the primary

treatment strategy for patients with wild-type EGFR NSCLC (10). Thus, identifying additional

treatment strategies for EGFR-resistant mutant and EGFR wild-type

NSCLC is important.

Ferroptosis is a newly discovered type of programmed

cell death that differs from apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy.

Ferroptosis is characterized by iron-dependent cell death, which

progresses with the accumulation of lipid peroxide and the

generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (12). During lipid peroxidation, the

activity of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) decreases, and

therefore lipid oxides cannot be metabolized through the

glutathione reductase reaction catalyzed by GPX4 (13,14).

The redox-active iron form (Fe2+) oxidizes lipids in a

manner similar to that of the Fenton reaction to produce large

amounts of ROS, causing an increase in malondialdehyde (MDA), which

promotes ferroptosis (15).

Ferritin is a major intracellular iron storage protein complex that

includes ferritin light-chain polypeptide 1 and ferritin

heavy-chain polypeptide 1 (FTH1) (16), and increased ferritin expression

limits ferroptosis (17). In

addition, iron levels are actively regulated in cells through

transferrin, which transports iron into the cells, and ferroportin,

which exports iron from the cells (18). The degradation of iron storage

proteins and changes in iron transporters can increase

iron-mediated ROS production, eventually leading to ferroptosis

(19). A study has shown that

inducing ferroptosis can improve therapeutic effects in

gefitinib-resistant lung cancer (20). In addition, another report has shown

that inducing ferroptosis enhances the cytotoxicity of erlotinib in

NSCLC cells, thereby overcoming erlotinib resistance (21), suggesting that inducing ferroptosis

may be an effective treatment for EGFR-TKI-resistant NSCLC.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT

signaling pathway is also associated with tumor development

(22). Mammalian target of

rapamycin (mTOR), an important serine/threonine protein kinase

downstream of PI3K/AKT, regulates the proliferation, survival,

invasion and metastasis of tumor cells by activating ribosomal

kinases (23). mTOR inhibitors

(notably RAD001, an oral rapamycin derivative) have been approved

by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for wider use in

antitumor clinical treatment, providing more treatment options for

patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), estrogen

receptor+ + HER2− breast cancer and other

solid tumors (24). A study has

shown that RAD001 promotes the death of T790M+ NSCLC

cells (25), suggesting that RAD001

is a potential treatment strategy for EGFR-TKI resistant tumors. In

addition, inhibition of mTOR overcomes lapatinib resistance by

inducing ferroptosis in NSCLC (26), suggesting that the regulation of

mTOR may promote ferroptosis and overcome EGFR-TKI resistance.

Other studies have shown that the induction of ferroptosis in

wild-type EGFR NSCLC enhances the therapeutic effect of cisplatin

(27) and overcomes cell resistance

to gefitinib (28). A previous

report also demonstrated that dual inhibition of the EGFR/mTOR

pathway had a significant antitumor effect on wild-type EGFR NSCLC

(29). However, whether mTOR

inhibition enhances the antitumor effect in EGFR-TKI-resistant

mutants and wild-type EGFR NSCLC by inducing ferroptosis and the

related mechanisms remain unknown.

The present study investigated the effect and

mechanism of targeting the mTOR pathway to regulate ferroptosis in

NSCLC with EGFR wild-type, EGFR sensitive mutant cells and

EGFR-resistant mutant cells through MTT assay, western blotting,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), ROS assay and MDA

assay.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human NSCLC (H1975, A549 and H3255) cell lines were

purchased from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The

Chinese Academy of Sciences and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (all from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator and routinely passaged every 3 days.

MTT assay

H1975, A549 and H3255 cells were seeded into 96-well

plates with 4×103 cells/well and treated with various

concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 µM) or

ferroptosis regulators, erastin (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16

µM), ferrostatin-1 (0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 µM) and RSL3

(0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 µM). After 24 h, these cells were

incubated with MTT reagent (20 µl/well) at 37°C for 4 h. Then the

supernatant was replaced with 150 µl/well DMSO. This mixture was

shaken for 10 min and the absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a

CLARIOstarPlus microplate reader (BMG Labtech GmbH).

Western blotting

The H1975, A549 and H3255 cells with different doses

of RAD001 or RSL3 treatment were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer

containing the protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The supernatant was centrifuged at

15,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min and a BCA protein assay kit (Takara

Bio, Inc.) was used to determine the concentration of proteins in

the samples. The extracted protein (50 µg/lane) was mixed with 5X

sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer (BioTeke Corporation),

which was loaded in a 10% gel (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

and the proteins were separated using SDS-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane

and the membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat milk at 22–24°C for 1.5

h. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with

different primary antibodies (listed below). After washing with

TBS-1% Tween 20 for three times, the membranes were incubated with

the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 h at 22–24°C (listed

below). The proteins were visualized using an enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (cat. no. P0018AS; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and analyzed with Quantity One software (version

4.6.9; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Primary antibodies against

Caspase 3/Cleaved-Caspase 3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 9662; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), FTH1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 3998; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), transferrin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab109503; Abcam),

transferrin receptor, CD71 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab84036; Abcam),

ferroportin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab235166; Abcam), GPX4 (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab125066; Abcam), phosphorylated (p-)mTOR (1:500; cat. no.

2971; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), mTOR (1:500; cat. no. 2972;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. 9272; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:1,000; cat. no. ab9485; Abcam), and

secondary antibodies against goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000; cat.

no. WLA023; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.) and goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000;

cat. no. WLA024; Wanleibio Co., Ltd.) were used.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

H1975, A549 and H3255 cells were seeded into a

6-well microplate at a density of 5×105 cells/well.

Total RNA from the cells in each group was extracted using TRIzol

reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. After RNA quality was tested, cDNA was

synthesized according to the manufacturer's protocols using a

PrimeScript II Reverse Transcriptase kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). qPCR

was then performed using a LightCycler 480 system (Roche

Diagnostics) and a SYBR Green Master Kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). The

reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 57°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec.

GAPDH mRNA was used to normalize relative mRNA levels. The relative

quantification of the PCR product was calculated, using the

2−ΔΔCq method (30).

Primer sequences are listed in Table

I.

| Table I.Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene name | Sense primer | Antisense

primer |

|---|

| xCT |

5′-TGGAACGAGGAGGTGGAGAA-3′ |

5′-TGGTGGACACAACAGGCTTT-3′ |

| FTH1 |

5′-CCAGAACTACCACCAGGACTC-3′ |

5′-GAAGATTCGGCCACCTCGTT-3′ |

| GPX4 |

5′-GCTGGACGAGGGGAGGAG-3′ |

5′-GGAAAACTCGTGCATGGAGC-3′ |

| Ferroportin |

5′-GAAAATCCCTGGGCCCCTTT-3′ |

5′-CTCTCGCTGAGGTGCTTGTT-3′ |

| Transferrin |

5′-CAGAAGCGAGTCCGACTGTG-3′ |

5′-CGCTTTTCATATGGTCGCGG-3′ |

| Transferrin

receptor |

5′-GGACGCGCTAGTGTTCTTCT-3′ |

5′-CATCTACTTGCCGAGCCAGG-3′ |

| GAPDH |

5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ |

5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ |

ROS assay

H1975, A549 and H3255 cells with different doses of

RAD001 treatment were seeded into a 6-well microplate at a density

of 3×105 cells/well. After 24 h of treatment with RAD001

(0, 0.5, 1, 8 µM), the cells were collected, 10 µmol/l DCFH-DA was

added and the reaction mixture and was incubated at 37°C for 20

min. The cells were then washed three times with serum-free cell

culture medium of RPMI 1640 and the rate of ROS was detected using

a flow cytometer (FACSCanto; BD Biosciences). The results were

analysed using BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

MDA assay

H1975, A549 and H3255 cells with different doses of

RAD001 treatment were seeded into a 6-well microplate at a density

of 3×105 cells/well. After 24 h of treatment with RAD001

(0, 0.5, 1, 8 µM), the cells were collected and the levels of

intracellular MDA were measured using a Lipid Peroxidation MDA

Assay Kit (cat. no. S0131S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.)

and GraphPad Prism (version 6.01; Dotmatics) software. Statistical

data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way

analysis of variance was used to compare the means among three or

more groups. Dunnett's test was used for all comparisons against a

single control. P-values were based on two-tailed statistical

analyses. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Different EGFR genotypes of NSCLC have

a different sensitivity to ferroptosis inducers

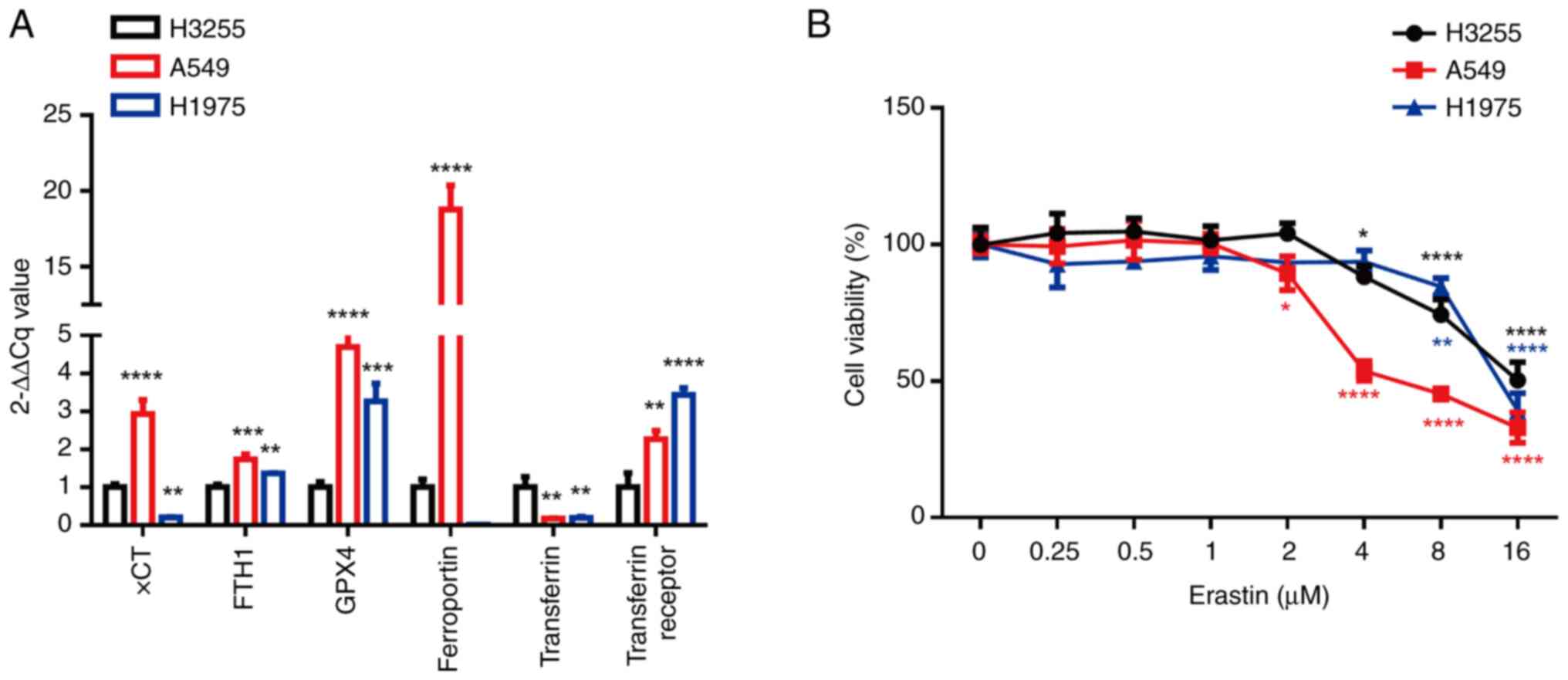

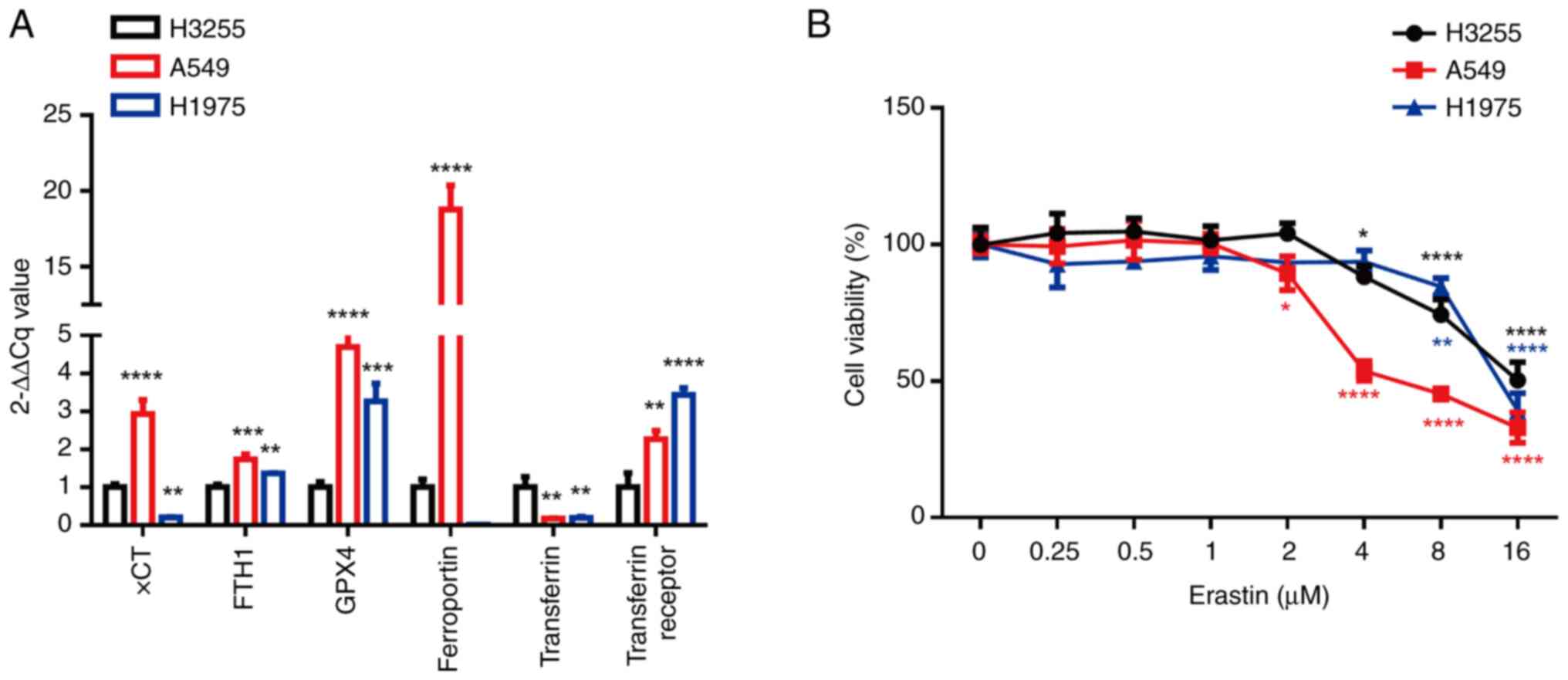

To explore the sensitivity of wild-type EGFR and

EGFR-mutated NSCLC cells to ferroptosis, the expression levels of

ferroptosis markers in H1975, A549 and H3255 cells were first

detected. When compared with H3255 (EGFR L858R mutation) cells, the

expression levels of FTH1, GPX4 and the transferrin receptor were

higher and the level of transferrin was lower in H1975 (EGFR

T790M/L858R) and A549 (EGFR wild type) cells (Fig. 1A). However, compared with H3255, the

expression levels of xCT and ferroportin were notably higher in

A549, but not H1975. When the A549, H1975 and H3255 cells were

treated with the ferroptosis inducer, erastin, cell death was

induced in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with H3255/A549 cells,

H1975 cells were more sensitive to erastin (IC50: 15.66

µM vs. 6.989 µM vs. 13.83 µM, Fig.

1B). These results suggest that the NSCLC cell lines with

wild-type EGFR and EGFR T790M/L858R mutations were more prone to

erastin-induced ferroptosis.

| Figure 1.Different epidermal growth factor

receptor mutant non-small cell lung cancer cell lines have a

different sensitivity to a ferroptosis inducer. (A) mRNA expression

levels of ferroptosis markers (xCT, FTH1, GPX4, ferroportin,

transferrin and the transferrin receptor) in A549, H1975 and H3255

cells were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. H3255 cells

using Dunnett's test. (B) A549, H1975 and H3255 cells were treated

with different concentrations of erastin (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and

8 µM) and the MTT assay was used to detect the cell viability after

24 h. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ****P<0.0001 vs. the control

group (0 µM of Erastin) using Dunnett's test. xCT,

cysteine-glutamate antiporter; FTH1, ferritin heavy-chain

polypeptide 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4. |

Inhibition of mTOR may induce

ferroptosis in EGFR-TKI resistant mutant and EGFR wild-type

NSCLC

To explore whether RAD001 regulates ferroptosis in

NSCLC with different EGFR mutations, H3255 (EGFR-TKI-sensitive),

H1975 (EGFR-TKI-resistant) and A549 (EGFR wild-type) cells were

treated with RAD001 at different concentrations. It was found that

as the drug concentration increased, cell viability gradually

decreased in a dose-dependent manner. Compared with H3255 cells,

H1975 and A549 cells were more sensitive to RAD001

(IC50: 4.474 mM vs. 8.869 µM vs. 50.79 µM; Fig. 2A). Since ferroptosis is a form of

apoptosis independent cell death, it was first tested whether

different concentrations of RAD001 induce cell apoptosis, and then

explored which concentration of RAD001 might induce ferroptosis.

The three cell types were treated with low- and high-dose RAD001.

Only 0.5 and 1 µΜ RAD001 treatment in A549 cells induced an

increase in cleaved-Caspase3/Caspase3 (Fig. 2B-D). The three cell lines were then

treated with RAD001, ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) and RAD001 + Fer-1,

respectively. The results showed that compared with RAD001 (1 µM)

control, Fer-1 reduced the cell death induced by RAD001 (1 µM) in

H1975 and A549 cells obviously. The difference was statistically

significant. However, Fer-1 did not reverse cell death in H3255

cells (Fig. 2E-G).

| Figure 2.RAD001 may regulate ferroptosis in

EGFR T790M/L858R and wild type EGFR non-small cell lung cancer. (A)

H3255, A549 and H1975 cells were treated with different

concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 µM).

After 24 h, cell viability was detected using MTT. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. the control group (0 µM of

RAD001) using Dunnett's test. (B) H3255, (C) A549 and (D) H1975

cells were treated with different concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.5,

1 and 8 µM) for 24 h and cleaved-Caspase3/Caspase3 was detected

using western blotting. GAPDH was used as an internal standard. (E)

H3255, (F) A549 and (G) H1975 cells were treated with different

concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.5 and 1 µM) combined with Fer-1 (0,

0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 µM). After 24 h, the cell viability

was detected using MTT. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and

****P<0.0001 vs. the control group (0 µM of Fer-1) using

Dunnett's test. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GAPDH,

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1. |

mTOR inhibitor combined with an

ferroptosis inducer promotes ferroptosis in EGFR resistant mutant

and wild type EGFR NSCLC cells

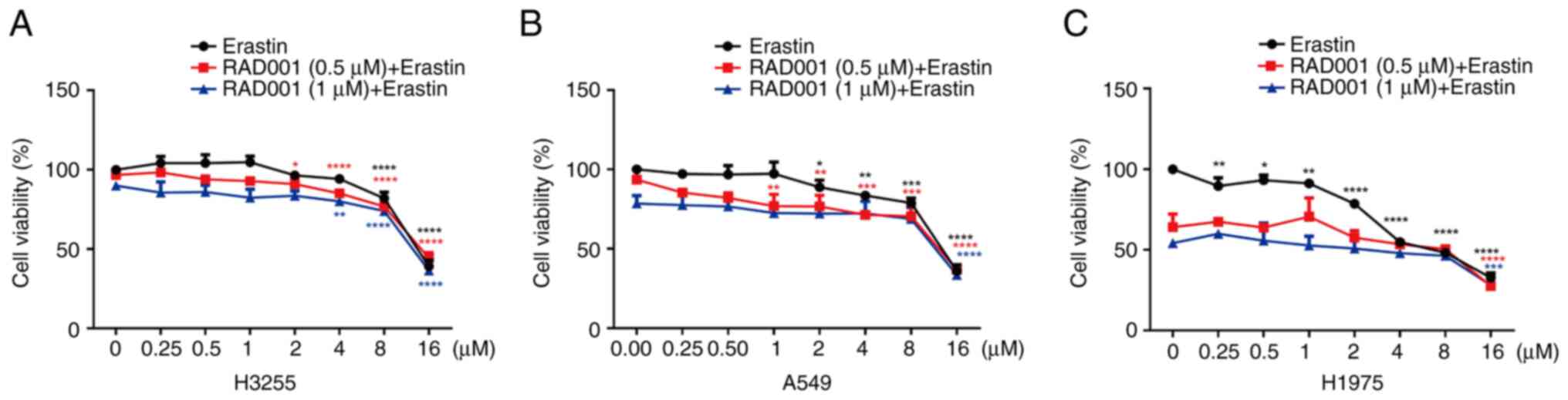

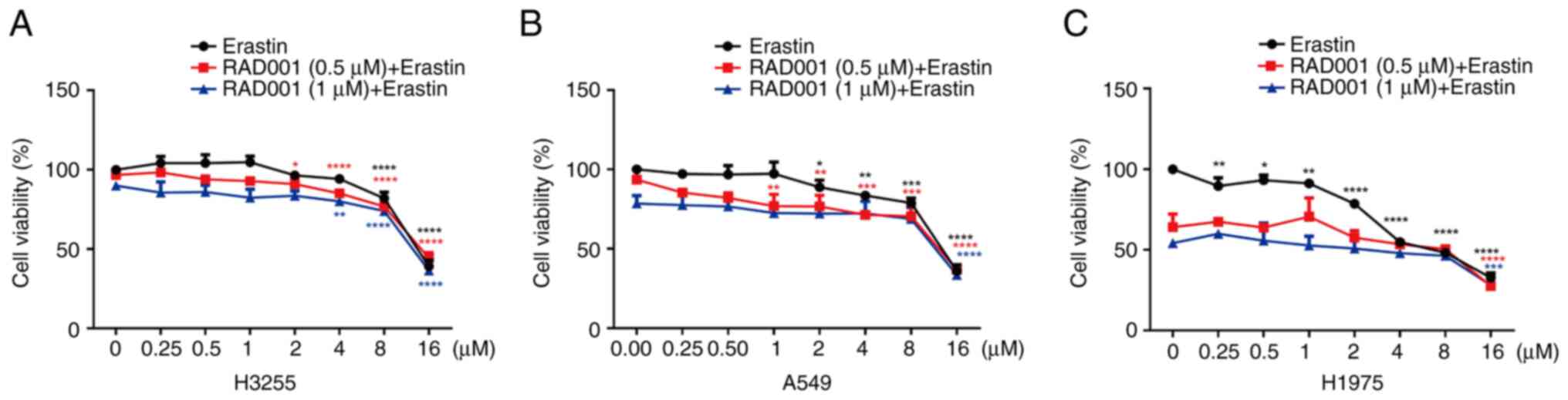

The H3255, A549 and H1975 cells were treated with

RAD001, erastin (ferroptosis inducer) and RAD001 + erastin,

respectively. After 24 h, the results showed that erastin induced

H1975, A549 and H3255 cell death in a dose-dependent manner. In

addition, compared with H3255/A549 cells, H1975 cells were more

sensitive to RAD001 combined with erastin. The IC50s of

RAD001 (0.5 µM) + erastin were 15.15, 15.35 and 4.106 µM in H3255,

A549 and H1975 cells, respectively. The IC50s of RAD001

(1 µM) + erastin were 15.87, 15.46 and 1.653 µM in H3255, A549 and

H1975 cells, respectively (Fig.

3A-C).

| Figure 3.RAD001 combined with erastin promotes

ferroptosis in EGFR T790M/L858R and wild-type EGFR non-small cell

lung cancer. (A) H3255, (B) A549 and (C) H1975 cells were treated

with different concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.5 and 1 µM) combined

with erastin (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 µM). After 24 h, the

cell viability was detected using MTT. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. the control group (0 µM of

erastin) using Dunnett's test. EGFR, epidermal growth factor

receptor. |

Inhibiting mTOR promotes ferroptosis

in EGFR resistant mutant and wild-type EGFR NSCLC cells by inducing

lipid peroxidation

H3255, A549 and H1975 cells were treated with low or

high concentrations of RAD001 (Fig.

4A-C). The results showed that 0.5, M and 8 µM of RAD001

inhibited mTOR activity by 56, 43 and 40% in A549 cells,

respectively. In addition, 0.5, 1 and 8 µM of RAD001 inhibited mTOR

activity by 5, 14 and 22% in H1975 cells, respectively. However,

these concentrations of RAD001 did not inhibit mTOR activity in

H3255 cells. It was found that 8 µΜ RAD001 significantly decreased

the expression of GPX4, FTH1 and ferroportin by 43, 31 and 22%,

respectively, in A549 cells and by 41, 29 and 26% in H1975 cells,

respectively. However, RAD001 did not markedly alter GPX4, FTH1 or

ferroportin expression in H3255 cells. Following treatment with

different concentrations of RAD001 in A549, H3255 and H1975 cells

for 4 h, high concentrations (8 µM) of RAD001 significantly induced

the accumulation of ROS by 52, 33 and 55% in these three types of

cells, respectively (Fig. 4D).

Moreover, 8 µM RAD001 increased the level of MDA by 23% in A549

cells and by 31% in H1975 cells, respectively. However, 8 µM of

RAD001 did not significantly alter MDA in H3255 cells (Fig. 4E). These results suggested that

RAD001 induced lipid peroxidation in EGFR-resistant mutant and

wild-type EGFR NSCLC cells by inhibiting mTOR, leading to

ferroptosis.

| Figure 4.Effect of RAD001 on ferroptosis

related proteins and ROS in EGFR T790M/L858R and wild-type EGFR

non-small cell lung cancer. (A) H3255, (B) A549 and (C) H1975 cells

were treated with different concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.5, 1 and

8 µM). After 24 h, the expression levels of p-mTOR, mTOR, GPX4,

FTH1, ferroportin, transferrin and the transferrin receptor were

detected using western blotting. GAPDH was used as an internal

standard. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. the control group (0 µM of RAD001) using

Dunnett's test. (D) H3255, A549 and H1975 cells were treated with

different concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.5, 1 and 8 µM) for 4 h.

The ROS levels were detected using flow cytometry. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the control group (0 µM of

RAD001) using Dunnett's test. (E) H3255, A549, and H1975 cells were

treated with different concentrations of RAD001 (0, 0.5, 1, and 8

µM) for 4 h. The accumulation of lipid peroxidation was detected

using an MDA kit *P<0.05 and ****P<0.0001 vs. the control

group (0 µM of RAD001) using Dunnett's test. EGFR, epidermal growth

factor receptor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; MDA, malondialdehyde; p-,

phosphorylated; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; FTH1, ferritin

heavy-chain polypeptide 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4. |

Inhibition of GPX4 inhibits AKT/mTOR

and promotes ferroptosis in EGFR resistant mutant NSCLC cells

To clarify the regulatory relationship between mTOR

and GPX4, H3255, A549 and H1975 cells were treated with the GPX4

inhibitor, RSL3. The results showed that RSL3 notably inhibited

cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, compared

with A549 and H1975 cells, H3255 cells were the most sensitive to

RSL3 (Fig. 5A). H1975, A549 and

H3255 cells were also treated with different concentrations of

RAD001 in combination with RSL3. Subsequent, western blotting

showed that high-dose RAD001 markedly inhibited the AKT/mTOR

pathway in H1975 and A549 cells compared with H3255 cells.

High-dose RSL3 inhibited AKT/mTOR pathway notably in H1975 cells

and the combination of RAD001 and RSL3 further enhanced the

inhibitory effect on the AKT/mTOR pathway in this type of cells;

however, this effect was not observed in A549 cells, possibly due

to the low mTOR expression in A549 cells (Fig. 5B-D).

| Figure 5.Inhibition of GPX4 inhibits mTOR/AKT

pathway of EGFR T790M/L858R and wild-type EGFR non-small cell lung

cancer cells. (A) H3255, A549 and H1975 cells were treated with

different concentrations of RSL3 (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16

µM) for 24 h. The cell viability was detected using MTT.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. the control

group (0 µM of RSL3) using Dunnett's test. (B) H1975, (C) A549 and

(D) H3255 cells were treated with different concentrations of

RAD001 (0, 0.5, 1 and 8 µM) combined with RSL3 (0, 0.1 and 0.5 µM).

After 24 h, the expression of p-mTOR, mTOR and AKT were detected

using western blotting, and GAPDH expression was used as an

internal standard. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GAPDH,

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; p-, phosphorylated; mTOR,

mammalian target of rapamycin. |

Discussion

TKIs have greatly changed the clinical prospects of

patients with NSCLC with EGFR activation mutations (31). Although disease control is prolonged

and the tumor response rate is high, all patients eventually

progress after EGFR-TKI treatment (32). Therefore, there is an urgent need to

develop novel treatment strategies for these patients. In addition,

if there are no co-mutations in driving genes such as anaplastic

lymphoma kinase and ROS1, it is difficult for patients with NSCLC

with wild-type EGFR to benefit from targeted therapy. In the

present study, compared with H3255 cells harboring the EGFR L858R

mutation, H1975 cells with the EGFR T790M/L858R mutation and A549

cells with the EGFR wild-type mutation were more sensitive to the

ferroptosis inducer, erastin, suggesting that targeted ferroptosis

may be a potential treatment against EGFR T790M/L858R resistant

mutant and wild-type NSCLC. In addition, A549 cells harbor the KRAS

G12S mutation. KRAS mutation is a common carcinogenic driver

mutation that accounts for ~35% of lung adenocarcinomas (33). Although sotorasib (AMG510), a drug

targeting the KRAS G12C mutation, has been approved by the FDA as a

second-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with

the KRAS G12C mutation (34), there

are no approved targeted drugs for other KRAS mutation types

(35). A study has shown that KRAS

mutations are associated with EGFR-TKI resistance (36). In NSCLC, 15–30% of patients with

adenocarcinoma have functional mutations in the KRAS gene, which

means that the tumors in these patients do not respond to EGFR-TKIs

(37). The targeted regulation of

ferroptosis has a significant antitumor effect on EGFR-TKI

resistant NSCLC treated with EGFR-TKIs such as gefitinib (20). Therefore, based on the findings of

the present and aforementioned studies, the regulation of

ferroptosis may be an effective treatment strategy against tumors

harboring KRAS G12S and EGFR-TKI resistance.

Abnormal activation of mTOR is common in a variety

of cancer types such as lung adenocarcinoma, lymphoma and melanoma

(38–40), and is related to its role as a key

effector downstream of several carcinogenic pathways, such as

PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK, as well as tumor inhibitory pathways,

such as p53 and LKB1 (38,41–44). A

study has shown that mTOR is an important target for the regulation

of ferroptosis in many types of tumor cells, like breast cancer and

prostate cancer (45). The results

of the present study showed that, compared with EGFR L858R mutant

NSCLC, EGFR T790M/L858R and EGFR wild-type NSCLC were more

sensitive to the mTOR inhibitor, RAD001. RAD001-induced cell death

in these two cell types was reduced by the ferroptosis inhibitor,

Fer-1. Data from a clinical study suggest that mTOR inhibitors, as

single drugs, typically have relatively moderate therapeutic

effects, possibly due to the lack of strong cytotoxic effects

induced by these inhibitors (40).

RAD001 has been approved for the treatment of advanced renal cell

carcinoma, PNET and advanced breast cancer (46). However, designing an appropriate

combination therapy to enhance the cytotoxicity induced by mTOR

inhibition remains an unmet demand in clinical research (40). Recent preclinical studies have

further proven that co-targeting mTOR and ferroptosis may be a

promising cancer treatment strategy (45,47,48).

The results of the present study showed that compared with EGFR

L858R mutant NSCLC cells/EGFR wild-type NSCLC cells, EGFR

T790M/L858R mutant NSCLC cells were more sensitive to RAD001

combined with the ferroptosis inducer, erastin, suggesting that the

combination of mTOR inhibitor and erastin may be a potential

treatment strategy for EGFR-resistant mutant NSCLC cells.

mTOR complex 1 mediates cystine-induced GPX4 protein

synthesis, inhibits lipid peroxidation and protects cells from

ferroptosis (40). The results of

the present study showed that RAD001 markedly reduced mTOR activity

in EGFR T790M/L858R mutant and wild-type NSCLC cells, resulting in

decreased GPX4 protein levels and increased ROS levels. Therefore,

the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition of mTOR-induced

ferroptosis may be related to the accumulation of lipid

peroxidation caused by the reduction in GPX4. In addition, the

results of the present study demonstrated that the inhibition of

mTOR not only changed the expression of GPX4 protein but also

reduced the expression of the iron storage protein, FTH1, and the

iron transporter, ferroportin. Since FTH1 and ferroportin have

important roles in the regulation of iron metabolism in cells,

their reduction can lead to iron metabolism disorders and induce

ferroptosis (49). The results of

the present study indicated that inhibition of mTOR induced

ferroptosis in EGFR T790M/L858R mutant and wild-type NSCLC cells by

inducing lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism disorder. In

addition, the effect of GPX4 regulation on the AKT/mTOR pathway was

observed and it was found that GPX4 inhibition effectively

inhibited the AKT/mTOR pathway in H1975 cells. This may be related

to the positive regulatory relationship between AKT/mTOR and GPX4

(50,51). Notably, compared with H1975 and A549

cells, H3255 cells were the most sensitive to the GPX4 inhibitor,

RSL3, and the least sensitive to erastin, which may be related to

the different mechanisms of these drugs. Erastin exerts a

significant antitumor effect on wild-type EGFR cells by inducing

ROS-mediated caspase-independent cell death (52). Erastin binds directly to

voltage-dependent anion channel 2 and produces ROS in an

NADH-dependent manner, leading to mitochondrial damage. In certain

tumor cells with activated mutations, erastin induces cell death

via the RAS/RAF/MEK pathway (53).

Another study has shown that RSL3 inactivated GPX4, induced ROS

production by lipid peroxidation and rapidly induced ferroptosis in

RAS-mutant cells (54). Therefore,

for NSCLC with different EGFR mutations, different drugs that

regulate ferroptosis may be selected to achieve the most effective

antitumor effects. There were certain limitations to the present

study. In this study, H1975 (EGFR T790M/L858R), H3255 (EGFR L858R)

and A549 (EGFR wild type) cells were selected to test our

hypothesis. Experiments performed on other EGFR-mutant NSCLC types

of cells would strengthen the significance of the present results

and conclusion. The experiments using in vivo animal models

could also provide more robust results. Moreover, small cell lung

cancer (SCLC), squamous cell lung cancer or large cell

neuroendocrine lung carcinoma cell lines were not screened. Bebber

et al (55) reported that

non-neuroendocrine SCLC is vulnerable to ferroptosis. In our

ongoing study, it was found that, compared with neuroendocrine

SCLC, non-neuroendocrine SCLC cells with upregulated GPX4

expression were not sensitive to mTOR inhibitors. Therefore,

targeting mTOR may not induce ferroptosis by inhibiting GPX4 in

SCLC. We will further explore the role and molecular mechanism of

targeting mTOR to regulate ferroptosis in NSCLC, SCLC and large

cell neuroendocrine lung carcinoma.

In conclusion, the sensitivity of different EGFR

mutation types to ferroptosis was described in the present study

and the induction of ferroptosis by targeting mTOR was confirmed to

be a potential treatment strategy for EGFR T790M/L858R and

wild-type EGFR NSCLC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work was supported by the Health and Family Planning

Commission of Jilin Province (grant no. 2021JC095) and the

Department of Science and Technology of Jilin Province (grant no.

YDZJ202301ZYTS512).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC, HL, CJW and RZ designed the study; RZ and TXW

performed the experiments; RZ and CYH analyzed the data; CJW and RZ

wrote the manuscript. YLJ performed flow cytometry. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. CJW and RZ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2011: The impact of eliminating socioeconomic

and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J

Clin. 61:212–236. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ochi N, Takeyama M, Miyake N, Fuchigami M,

Yamane H, Fukazawa T, Nagasaki Y, Kawahara T, Nakanishi H and

Takigawa N: The complexity of EGFR exon 19 deletion and L858R

mutant cells as assessed by proteomics, transcriptomics, and

metabolomics. Exp Cell Res. 424:1135032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hamaguchi R, Okamoto T, Sato M, Hasegawa M

and Wada H: Effects of an alkaline diet on EGFR-TKI therapy in EGFR

mutation-positive NSCLC. Anticancer Res. 37:5141–5145.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lim SH, Lee JY, Sun JM, Ahn JS, Park K and

Ahn MJ: Comparison of clinical outcomes following gefitinib and

erlotinib treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer patients

harboring an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in either

exon 19 or 21. J Thorac Oncol. 9:506–511. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liang H, Pan Z, Wang W, Guo C, Chen D,

Zhang J, Zhang Y, Tang S, He J and Liang W; written on behalf of

AME Lung Cancer Cooperative Group, : The alteration of T790M

between 19 del and L858R in NSCLC in the course of EGFR-TKIs

therapy: A literature-based pooled analysis. J Thorac Dis.

10:2311–2320. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, Chen YM,

Park K, Kim SW, Zhou C, Su WC, Wang M, Sun Y, et al: Afatinib

versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic

non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib,

or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): A phase

2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 13:528–538. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Walter AO, Sjin RT, Haringsma HJ, Ohashi

K, Sun J, Lee K, Dubrovskiy A, Labenski M, Zhu Z, Wang Z, et al:

Discovery of a mutant-selective covalent inhibitor of EGFR that

overcomes T790M-mediated resistance in NSCLC. Cancer Discov.

3:1404–1415. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ward RA, Anderton MJ, Ashton S, Bethel PA,

Box M, Butterworth S, Colclough N, Chorley CG, Chuaqui C, Cross DA,

et al: Structure- and reactivity-based development of covalent

inhibitors of the activating and gatekeeper mutant forms of the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). J Med Chem. 56:7025–7048.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Thress KS, Paweletz CP, Felip E, Cho BC,

Stetson D, Dougherty B, Lai Z, Markovets A, Vivancos A, Kuang Y, et

al: Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in

non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat Med.

21:560–562. 2015. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhou F and Zhou CC: Targeted therapies for

patients with advanced NSCLC harboring wild-type EGFR: What's new

and what's enough. Chin J Cancer. 34:310–319. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lee JK, Hahn S, Kim DW, Suh KJ, Keam B,

Kim TM, Lee SH and Heo DS: Epidermal growth factor receptor

tyrosine kinase inhibitors vs conventional chemotherapy in

non-small cell lung cancer harboring wild-type epidermal growth

factor receptor: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 311:1430–1437. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lee JY, Kim WK, Bae KH, Lee SC and Lee EW:

Lipid metabolism and ferroptosis. Biology (Basel).

10:1842021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Seibt TM, Proneth B and Conrad M: Role of

GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic

Biol Med. 133:144–152. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Badgley MA, Kremer DM, Maurer HC,

DelGiorno KE, Lee HJ, Purohit V, Sagalovskiy IR, Ma A, Kapilian J,

Firl CEM, et al: Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor

ferroptosis in mice. Science. 368:85–89. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wish JB: Assessing iron status: Beyond

serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 1

(Suppl 1):S4–S8. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh

HJ III, Kang R and Tang D: Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by

degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 12:1425–1428. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gkouvatsos K, Papanikolaou G and

Pantopoulos K: Regulation of iron transport and the role of

transferrin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1820:188–202. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fang X, Wang H, Han D, Xie E, Yang X, Wei

J, Gu S, Gao F, Zhu N, Yin X, et al: Ferroptosis as a target for

protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

116:2672–2680. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang C, Lu X, Liu X, Xu J, Li J, Qu T,

Dai J and Guo R: Carbonic anhydrase IX controls vulnerability to

ferroptosis in gefitinib-resistant lung cancer. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2023:13679382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu C, Jiang ZB, Shao L, Zhao ZM, Fan XX,

Sui X, Yu LL, Wang XR, Zhang RN, Wang WJ, et al: β-Elemene enhances

erlotinib sensitivity through induction of ferroptosis by

upregulating lncRNA H19 in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer.

Pharmacol Res. 191:1067392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Vasan N, Razavi P, Johnson JL, Shao H,

Shah H, Antoine A, Ladewig E, Gorelick A, Lin TY, Toska E, et al:

Double PIK3CA mutations in cis increase oncogenicity and

sensitivity to PI3Kα inhibitors. Science. 366:714–723. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Aylett CH, Sauer E, Imseng S, Boehringer

D, Hall MN, Ban N and Maier T: Architecture of human mTOR complex

1. Science. 351:48–52. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hasskarl J: Everolimus. Recent Results

Cancer Res. 211:101–123. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fujiwara R, Taniguchi Y, Rai S, Iwata Y,

Fujii A, Fujimoto K, Kumode T, Serizawa K, Morita Y, Espinoza JL,

et al: Chlorpromazine cooperatively induces apoptosis with tyrosine

kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutated lung cancer cell lines and

restores the sensitivity to gefitinib in T790M-harboring resistant

cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 626:156–166. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ni J, Chen K, Zhang J and Zhang X:

Inhibition of GPX4 or mTOR overcomes resistance to Lapatinib via

promoting ferroptosis in NSCLC cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

567:154–160. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lou JS, Zhao LP, Huang ZH, Chen XY, Xu JT,

Tai WC, Tsim KWK, Chen YT and Xie T: Ginkgetin derived from Ginkgo

biloba leaves enhances the therapeutic effect of cisplatin via

ferroptosis-mediated disruption of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis in EGFR

wild-type non-small-cell lung cancer. Phytomedicine. 80:1533702021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yan WY, Cai J, Wang JN, Gong YS and Ding

XB: Co-treatment of betulin and gefitinib is effective against EGFR

wild-type/KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung cancer by inducing

ferroptosis. Neoplasma. 69:648–656. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang Y, Chen Y, Mei Q, Chen Y, Yu S and

Xia S: Combined inhibition of the EGFR and mTOR pathways in EGFR

wild-type non-small cell lung cancer cell lines with different

genetic backgrounds. Oncol Rep. 29:2486–2492. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Singh S, Sadhukhan S and Sonawane A: 20

Years since the approval of first EGFR-TKI, gefitinib: Insight and

foresight. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1889672023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Morimoto K, Yamada T, Takeda T, Shiotsu S,

Date K, Tamiya N, Goto Y, Kanda H, Chihara Y, Kunimatsu Y, et al:

Clinical efficacy and safety of first- or second-generation

EGFR-TKIs after osimertinib resistance for EGFR mutated lung

cancer: A prospective exploratory study. Target Oncol. 18:657–665.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Reck M, Carbone DP, Garassino M and

Barlesi F: Targeting KRAS in non-small-cell lung cancer: Recent

progress and new approaches. Ann Oncol. 32:1101–1110. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nakajima EC, Drezner N, Li X,

Mishra-Kalyani PS, Liu Y, Zhao H, Bi Y, Liu J, Rahman A, Wearne E,

et al: FDA approval summary: Sotorasib for KRAS G12C-mutated

metastatic NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res. 28:1482–1486. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hofmann MH, Gerlach D, Misale S,

Petronczki M and Kraut N: Expanding the reach of precision oncology

by drugging all KRAS mutants. Cancer Discov. 12:924–937. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, Miller VA, Pan

Q, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF, Heelan RT, Kris MG and Varmus HE: KRAS

mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to

gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2:e172005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ, Boot AJ, Evers SG,

Mooi WJ, Wagenaar SS, van Bodegom PC and Bos JL: Incidence and

possible clinical significance of K-ras oncogene activation in

adenocarcinoma of the human lung. Cancer Res. 48:5738–5741.

1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Saxton RA and Sabatini DM: mTOR signaling

in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 168:960–976. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu GY and Sabatini DM: mTOR at the nexus

of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

21:183–203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lei G, Zhuang L and Gan B: mTORC1 and

ferroptosis: Regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic potential.

Bioessays. 43:e21000932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ and Jin S: The

coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:8204–8209. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, Lopez L,

Kosmatka M, DePinho RA and Cantley LC: The LKB1 tumor suppressor

negatively regulates mTOR signaling. Cancer Cell. 6:91–99. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Byun JK, Park M, Yun JW, Lee J, Kim JS,

Cho SJ, Lee YM, Lee IK, Choi YK and Park KG: Oncogenic KRAS

signaling activates mTORC1 through COUP-TFII-mediated lactate

production. EMBO Rep. 20:e474512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Prabowo AS, Iyer AM, Veersema TJ, Anink

JJ, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Spliet WG, van Rijen PC, Ferrier CH,

Capper D, Thom M and Aronica E: BRAF V600E mutation is associated

with mTOR signaling activation in glioneuronal tumors. Brain

Pathol. 24:52–66. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yi J, Zhu J, Wu J, Thompson CB and Jiang

X: Oncogenic activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling suppresses

ferroptosis via SREBP-mediated lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

117:31189–31197. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Hua H, Kong Q, Zhang H, Wang J, Luo T and

Jiang Y: Targeting mTOR for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol.

12:712019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang Y, Swanda RV, Nie L, Liu X, Wang C,

Lee H, Lei G, Mao C, Koppula P, Cheng W, et al: mTORC1 couples

cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis

regulation. Nat Commun. 12:15892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Liu Y, Wang Y, Liu J, Kang R and Tang D:

Interplay between MTOR and GPX4 signaling modulates

autophagy-dependent ferroptotic cancer cell death. Cancer Gene

Ther. 28:55–63. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Muhoberac BB and Vidal R: Iron, Ferritin,

hereditary ferritinopathy, and neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci.

13:11952019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Jung KH, Kim SE, Go HG, Lee YJ, Park MS,

Ko S, Han BS, Yoon YC, Cho YJ, Lee P, et al: Synergistic

renoprotective effect of melatonin and zileuton by inhibition of

ferroptosis via the AKT/mTOR/NRF2 signaling in kidney injury and

fibrosis. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 31:599–610. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hu Z and Li L, Li M, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Ran

J and Li L: miR-21-5p inhibits ferroptosis in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells by regulating the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

through MELK. J Immunol Res. 2023:89295252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yamaguchi H, Hsu JL, Chen CT, Wang YN, Hsu

MC, Chang SS, Du Y, Ko HW, Herbst R and Hung MC:

Caspase-independent cell death is involved in the negative effect

of EGF receptor inhibitors on cisplatin in non-small cell lung

cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 19:845–854. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yagoda N, von Rechenberg M, Zaganjor E,

Bauer AJ, Yang WS, Fridman DJ, Wolpaw AJ, Smukste I, Peltier JM,

Boniface JJ, et al: RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death

involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature. 447:864–868.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun

X, Kang R and Tang D: Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death

Differ. 23:369–379. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Bebber CM, Thomas ES, Stroh J, Chen Z,

Androulidaki A, Schmitt A, Höhne MN, Stüker L, de Pádua Alves C,

Khonsari A, et al: Ferroptosis response segregates small cell lung

cancer (SCLC) neuroendocrine subtypes. Nat Commun. 12:20482021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|