Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent

malignant cancers, with the third highest incidence and second

highest mortality rates among all cancers worldwide (1). Surgical resection offers a potentially

high probability of cure, with approximately 90% of the patients

having early-stage primary CRC. However, many patients are

diagnosed at advanced stages, resulting in lower cure rates

(2). According to recent research,

20–34% of patients newly diagnosed with CRC already exhibit

metastatic disease (3), and 50–60%

of individuals initially diagnosed with localized CRC eventually

develop metastases (4). In

particular, the liver is the most prevalent site for CRC

metastasis, and the lungs are the second most prevalent one,

accounting for approximately 10–18% of rectal and 5–6% of colon

cancers (5). Surgical resection and

chemotherapy are currently used to treat metastatic CRC. However,

the clinical outcomes of patients with distant metastases remain

poor, and the survival rate of patients with metastatic CRC remains

below 20% (6). Therefore, the

development of novel treatments based on an understanding of the

molecular mechanisms of CRC progression is required.

In previous studies on metastatic CRC, liver

metastasis is well investigated from the viewpoint of

pathophysiological and molecular aspects owing to its high

probability. During the process, TNF-α and IL-1β upregulate the

expression of E-selectin and other adhesion molecules on liver

sinusoidal endothelial cells and enhance liver metastases; VEGF

mediates the vascularization (7).

Compared to liver metastasis, lung metastasis is

thought to occur through different mechanisms. Lymphatic vessels in

the colon and systemic venous circulation play more significant

roles than those in the liver. Furthermore, the lung

microenvironment is considerably more enriched with several types

of immune cells that reside in the airways and alveoli than in the

liver stroma (8).

SMAD4-deficient CRC cells in a mouse model secrete CCL15,

which recruits CCR1+ tumor-associated neutrophils, resulting in

lung metastasis (9). NDRG1 plays an

important role in MORC2-mediated CRC cell migration and invasion in

vitro and promotes lung metastasis of CRC cells in vivo

(10). Lung metastases share

clonality with primary tumors (including KRAS, TP53, and

APC mutations) through extensive genomic profiling of

clinical samples from three patients with CRC (8). An animal study shows that HDAC1 plays

a key role in lung metastasis by inhibiting EMT (11). Microarray analysis using metastatic

lung tissue from six patients shows that 42 genes are upregulated

in lung metastasis compared to those in the original colon tumor

(12). Although these studies may

lead to novel treatments, there is no consensus on the mechanism of

lung metastasis since the results are inconsistent. We suspect that

the heterogeneity of the samples can lead to this problem because

most previous studies used a small number of tumor tissues derived

from patients with different treatment histories or genetic

backgrounds. Therefore, a more precise analysis of the mechanisms

underlying lung metastasis is required.

We aimed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying lung

metastasis of colorectal cancer. We used in vitro models to

overcome the heterogeneity of the clinical materials. It is

possible to obtain more accurate insights into lung metastasis by

utilizing the experimental animal models and cell lines that we

previously established since the mice we used were genetically

homogeneous and each cell line was a single population.

In this study, we compared the gene expression

profiles of the original cell line and cell lines established from

lung metastasis to reveal the molecular background of lung

metastasis in CRC. We found a unique difference in profilin 2

isoforms between primary and metastatic lung CRC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The CMT93-PM cell line was established in a previous

study (13). Briefly, CMT93 cells

(CCL-223; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were injected into the tail

veins of six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice. Twenty-five mice were

used for this experiment. Eight weeks after the tail vein

injection, all mice were euthanized by inducing anesthesia with

4.0% isoflurane and maintaining it with 2.0% isoflurane. Once

general anesthesia was achieved, they were quickly sacrificed by

exsanguination. The lungs were extracted and lung metastatic tumors

were visually identified. The tumor tissues were used for primary

tissue culture as previously described (13). The tumor cells were cultured and

maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich,

St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (v/v),

10,000 units/ml penicillin, 10,000 µg/ml streptomycin, and 25 µg/ml

Gibco amphotericin B (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) at

37°C with 5% CO2. Four metastatic tumors were subjected

to primary tissue culture. Tumor cells from one metastatic tumor

grew spontaneously, and the cells underwent more than 20 passages

over a period of three months. The cells were designated as

CMT93-PM and used in this study. Moreover, we assigned CMT93-PM

cell numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 according to the order in which they

were collected. All animals were housed in a controlled environment

at the Keio University School of Medicine under standard

temperature and light and dark cycles. All animal procedures were

approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Keio

University School of Medicine (approval no. 15006).

Evaluating metastatic potentials of

CMT93 and CMT93-PM

CMT93-PM and CMT93-PM1 cells were injected into the

eight-week-old male mice via the tail vein, as described above.

Twenty-nine mice were used for this experiment. The number of

metastatic tumors in the lungs was evaluated using computed

tomography (CT) Before euthanasia, pulmonary metastasis was

assessed using an X-ray micro-CT system (R_mCT2; Rigaku, Tokyo,

Japan) under mild inhalation anesthesia using isoflurane. Chest CT

operational parameters were set at 90 kV and 160 µA to utilize a

respiratory and cardiac reconstruction mode according to the

instruction manual. The field of view was 24×24 mm with a pixel

size of 50×50 m. The scanning duration was 4.5 min. The mice were

positioned prone to scanning, and inhalation anesthesia comprising

a mixture of isoflurane (Pfizer Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and oxygen was

administered via a nasal cone. The concentration of isoflurane was

maintained at 2.0% from induction to maintenance. The respiratory

and cardiac reconstruction modes allow X-ray images to be

exclusively captured during the diastolic phase of the heart within

the end-expiratory period. Imaging was performed by simultaneously

tracking the breathing and cardiac movements under radiographic

guidance. Examination was performed twice-at the 8 and 12th week

after injection- to confirm pulmonary metastases by comparing the

metachronous images obtained. All mice were euthanized at 12 weeks

by cervical dislocation under general anesthesia using 4.0%

isoflurane for induction. After euthanasia, the lungs were

extracted and fixed by injecting 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (1 ml)

through the trachea. The lung tissues were then immersed in 4% PFA

and stored at room 4°C for 48 h to facilitate fixation.

Subsequently, they were dehydrated in absolute ethanol at 25°C. The

tissues were embedded in paraffin, and the paraffin blocks were cut

into 4-µm thick sections. These sections were stained with Mayer's

hematoxylin solution for 15 min at 25°C, followed by rinsing in tap

water. Finally, staining was conducted with eosin Y ethanol

solution for 1 min at 25°C. Pathological evaluation of pulmonary

metastases was also conducted using Evos FL Auto2 microscope

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

RNA extraction and microarrays

Total RNAs were extracted from CMT93 and CMT93-PM1

cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Gene

expression profiles were obtained using the Affymetrix GeneChip

Mouse430_2 array following the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, the sense-strand cDNA was fragmented and labeled using the

Affymetrix GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling Kit (Santa Clara, CA, USA)

after generating single-stranded cDNA. Following hybridization, the

GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix) was used to wash the

arrays and scanning was performed using a GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G

(Affymetrix). The raw intensity data derived from the microarray

images were pre-processed using Affymetrix Expression Console

software (Affymetrix). Expression intensities were stored as cell

intensity files and normalized using the robust multi-chip average

method. Subsequently, these datasets were subjected to filtering,

with genes displaying an absolute fold change ≥2 or ≤0.5 identified

as exhibiting differential expression. Subsequently, we conducted

Gene Ontology analysis using the Database for Annotation,

Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) tool, and plotted

the enrichment scores for each cluster (14), which served as indicators of the

biological significance of these clusters.

Evaluating PFN2 expression using

real-time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and melting curve

analysis

To evaluate the expression pattern of PFN2 in

the cell lines, RT-PCR with high-resolution melting curve analysis

was sequentially performed on an LC480 platform (Roche Applied

Science, Mannheim, Germany) in a reaction mixture containing 5 µl

of 2×THUNDERBIRD™ Next SYBR® qPCR Mix, 1.2 µl of

profilin2-specific primer (forward: 5′-GCCTATACGTTGATGGTGACTG-3′,

and reverse: 5′-ACAAAGACCAAGACTCTCCCG-3′), 1 µl of cDNA and 2.8 µl

of DNase-free water in a total reaction volume of 10 µl per sample.

GAPDH (Hs99999903_m1) purchased from Applied Biosystems

(Foster City, CA, USA) was used as a control. Two micrograms of

total tissue RNA were reverse transcribed to generate cDNA using

the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City,

California, United States). The reaction conditions involved enzyme

activation at 95°Cx30 sec, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at

95°Cx5 sec, 53°Cx20 sec for annealing, and 60°Cx30 sec for

extension (15). To analyze the

relative changes in the quantitative RT-PCR, we employed the

2(−ΔΔCt) method (16). Following

these reactions, high-resolution melting curve analysis was

conducted by heating the mixture from 60–99°C using a ramping

degree of 4.8°C/sec.

Detecting profilin splice forms by

RT-PCR/Sanger sequencing

Real time PCR was performed and analyzed following

the previously described protocol (15,16).

cDNA was generated as described above. Polymerase chain reaction

amplification was performed using profilin 2-specific

primers. The same 3′ primer (5′-GAGTCAAGGTGGGGAGCCAAC3′) and a

unique internal 5′ primer (PFN2A: 5′-TCAAGTATTTTGCCATTGAGTATGCC3′,

PFN2B: 5′-CCTCTTCAGGTATAAAGCGAGTTC3′) were used. The PCR products

were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The PCR products were purified

using the ExoSAP-IT® Express PCR Product Clean-up

(Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California, United States) as per the

manufacturer's instructions. Sanger sequencing reactions were

prepared using the BigDye™ Terminator version 3.1 kit (Applied

Biosystems, Foster City, California, United States) as per the

manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the sequencing reaction

consisted of 1.75 µl Sequencing Reaction Mix (BigDye™ Terminator

v3.1), 1 µl Sequencing Buffer (BigDye™ Terminator v1.1), 4.75 µl

nuclease-free water, 1 µl forward primer, 1 µl reverse primer and 1

µl PCR product. The sequencing reaction was subjected to the

following cycling conditions in a 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied

Biosystems, Foster City, California, United States): one cycle at

96°C for 1 min, and 25 cycles at 96°C for 13 sec, 50°C for 8 sec,

and 60°C for 4 min. Sequence reactions were cleaned up with the

AxyPrep Mag DyeClean Kit (Axygen, Union City, CA, United States) as

per the manufacturer's instructions. Sequence raw reads were loaded

onto the Seq studio Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems) with

Tracking Dye, Hi-Di™ Formamide (PE Applied Biosystems, Fostercity

CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as means (± standard

deviations) without any notation. All statistical analyses were

performed using Stata software ver.14.2 (Stata Corp., College

Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Hierarchical clustering was performed using TAC software (Thermo

Fisher Scientific), which utilizes the Euclidean distance metric

and complete linkage method for clustering. The χ2 test

was performed to compare the original and pulmonary metastatic

cells, and ANOVA followed by Bonferroni as a post hoc test were

used for the other comparisons without any notation.

Results

Evaluating the potential for lung

metastasis of CMT93-PM cells and their original counterpart cells,

CMT93

CMT93 is a commercially available cell line isolated

from the rectum of a mouse with polypoid carcinoma and CMT93-PM1-4

are cell lines that we previously established from lung metastasis

of CMT93 caused by tail vein injection (13). Initially, we confirmed the superior

metastatic function of CMT93-PM1 compared with that of CMT93.

CMT93-PM1 cells demonstrated a much more aggressive metastatic

function than CMT93 cells using the tail vein injection method in

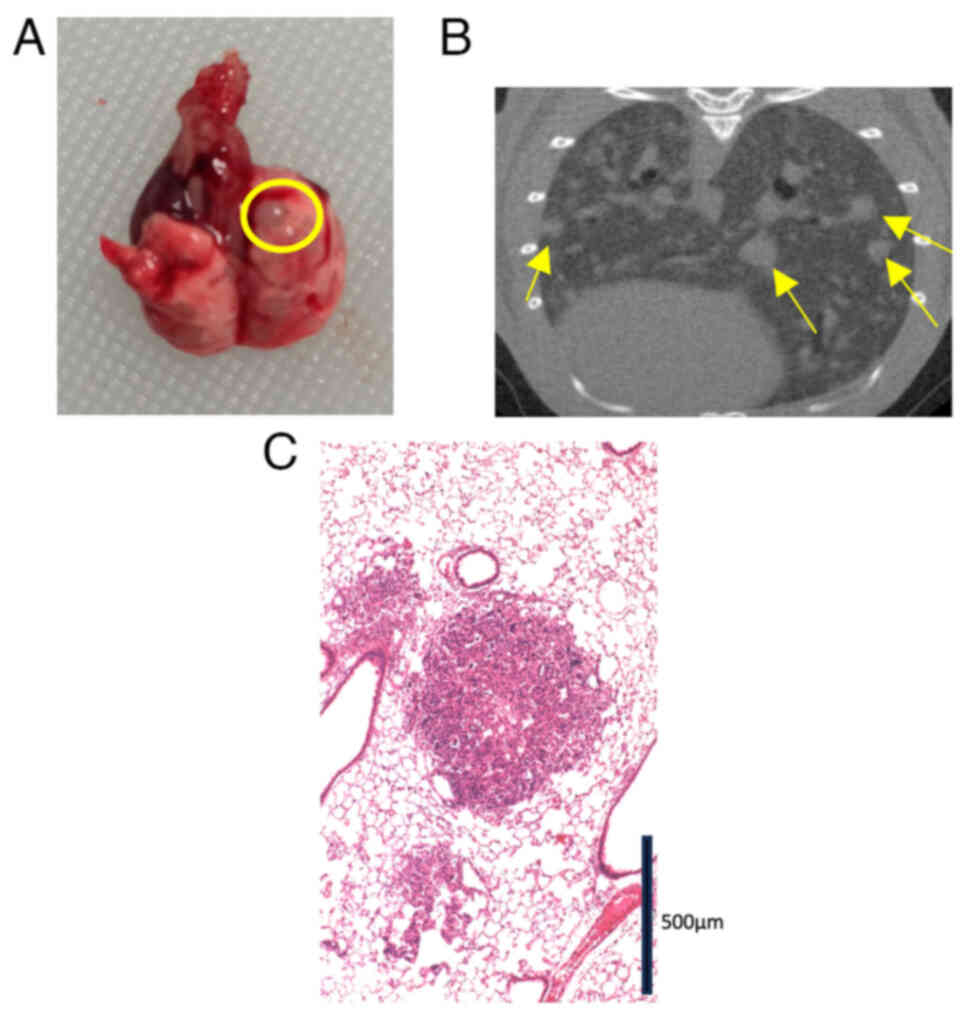

29 mice (Fig. 1). Visual inspection

(Fig. 1A) and CT (Fig. 1B) revealed numerous metastatic

tumors. We microscopically confirmed a metastatic lung lesion

(Fig. 1C). Although the rate of

lung metastasis was only 13.3% (2/15) in the CMT93 group, the

CMT93-PM1 group showed a 100% metastasis rate (14/14) (P<0.001)

(Table I).

| Table I.Comparison of lung metastasis rates

between CMT93 and CMT93-PM1. |

Table I.

Comparison of lung metastasis rates

between CMT93 and CMT93-PM1.

| Cell line | Total mice, n | Mice with lung

metastasis, n | Rate of lung

metastasis, % | P-value |

|---|

| CMT93 | 15 | 2 | 13.3 | P<0.001 |

| CMT93-PM1 | 14 | 14 | 100.0 |

|

Microarray, cluster analysis, and

enrichment analysis by DAVID

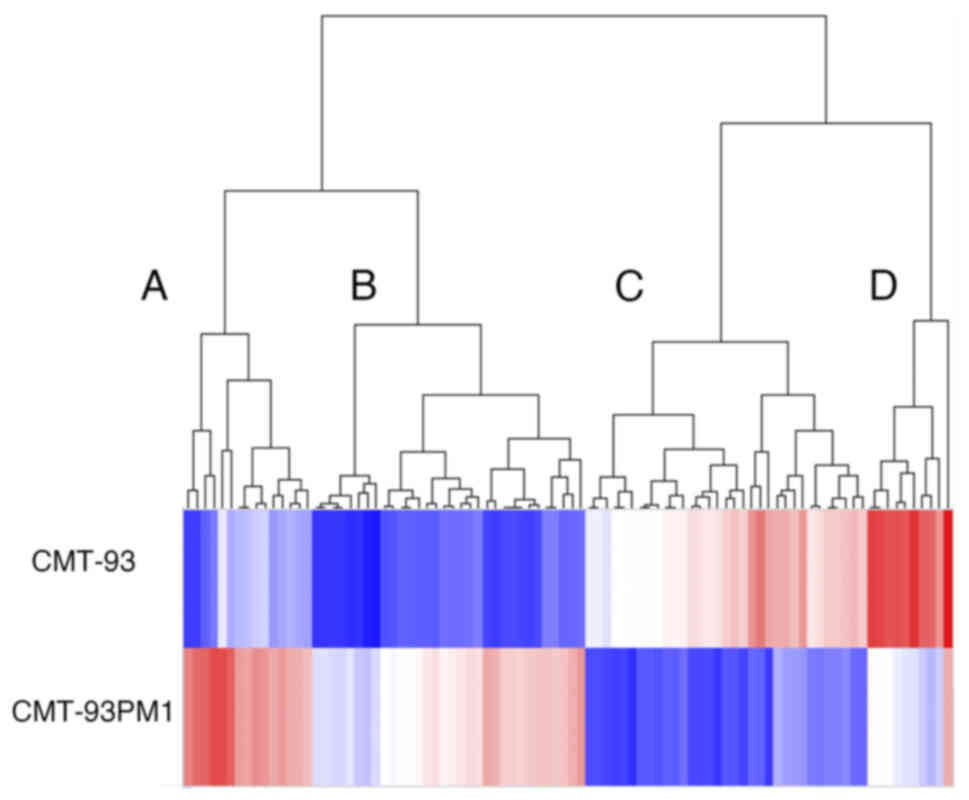

We analyzed the gene expression profiles using

microarray analysis to investigate the mechanisms underlying lung

metastasis. We observed that 2241 and 88 genes showed differential

expression CMT93 and CMT93-PM1 with a fold change of more than 2.0

and 10, respectively (Fig. 2).

Among these 88 genes, 46 were upregulated and 42 were

downregulated. The 88 genes were further divided into two groups

using clustering analysis: genes that were upregulated or

downregulated in CMT93-PM1 cells. The genes in these two groups

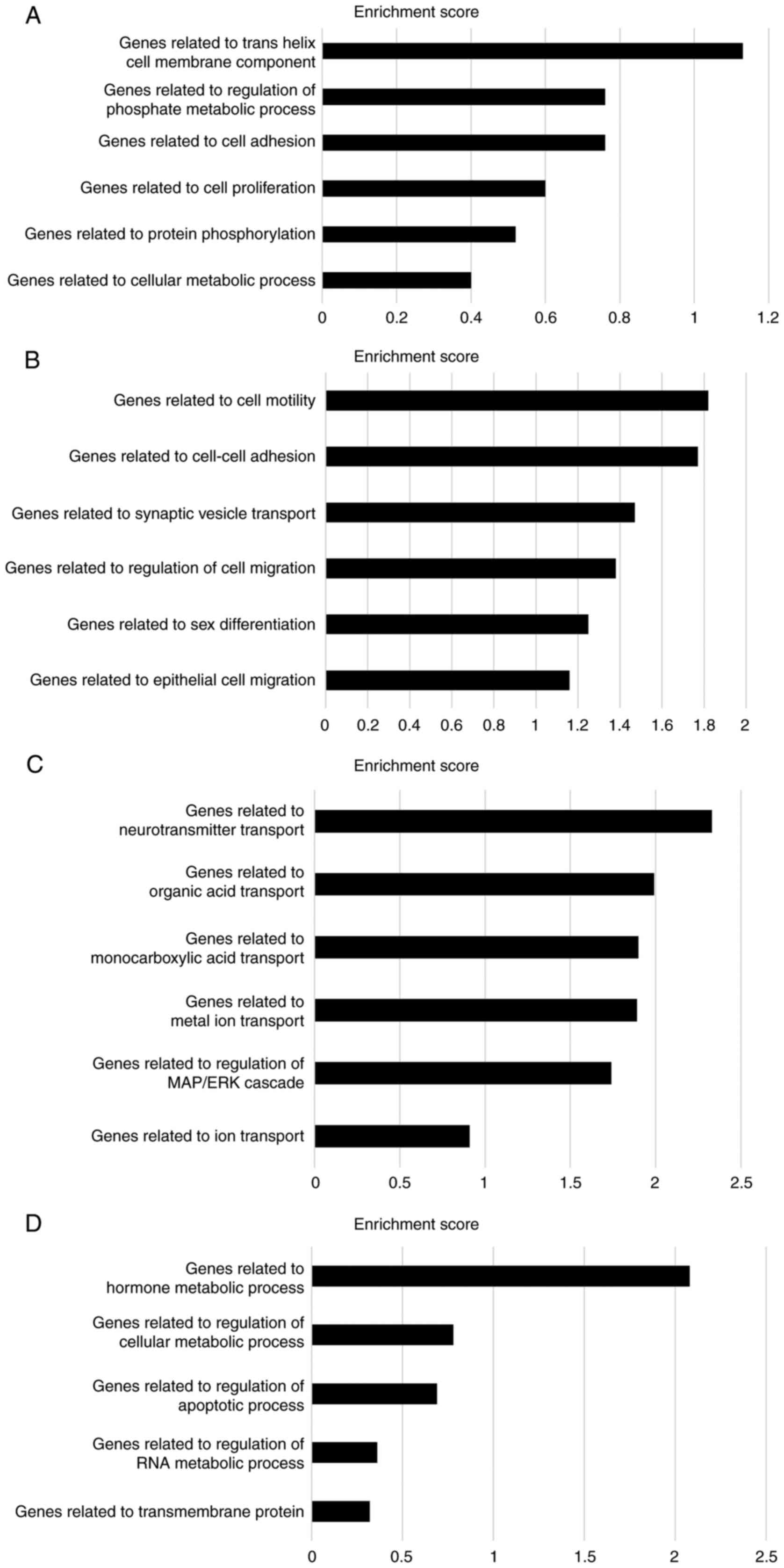

were further subdivided into two groups. Cluster A (the most

upregulated cluster in CMT93-PM1 cells compared to that in CMT93

cells) demonstrated phosphate metabolic processes, cell adhesion,

cell proliferation, protein phosphorylation, and cellular metabolic

processes. Cluster B (which included profilin 2) demonstrated

upregulation of genes related to cell motility, adhesion, and

migration. Clusters C and D consisted of genes that were

downregulated in CMT93-PM1 cells compared to those in CMT93 cells.

Cluster C contains several genes related to molecular transport.

Cluster D contains genes related to hormone metabolism and

regulation of cellular metabolic processes (Fig. 3A-D).

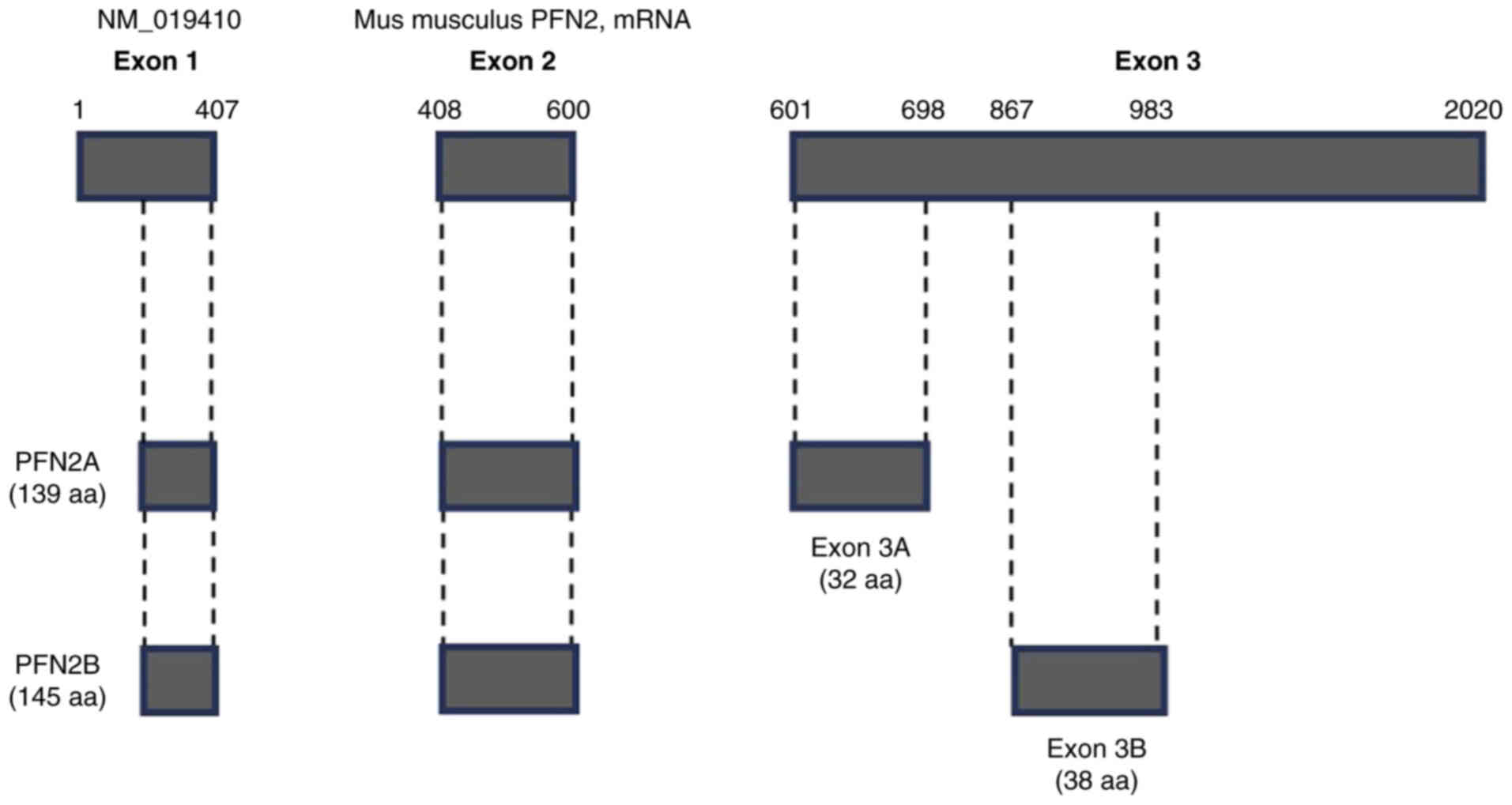

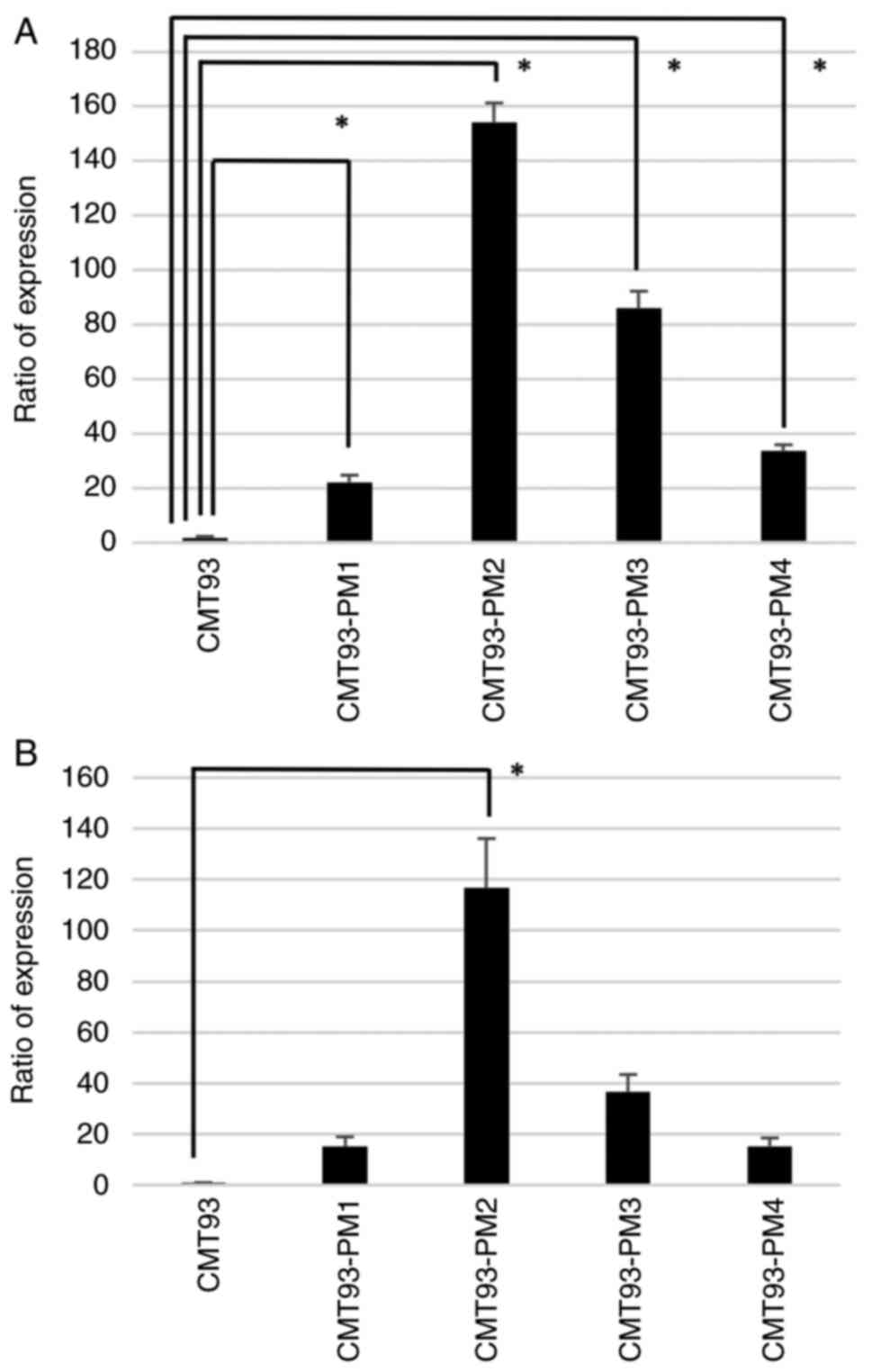

Evaluating PFN2 expression in CMT93-PM

using RT-PCR and melting curve analysis

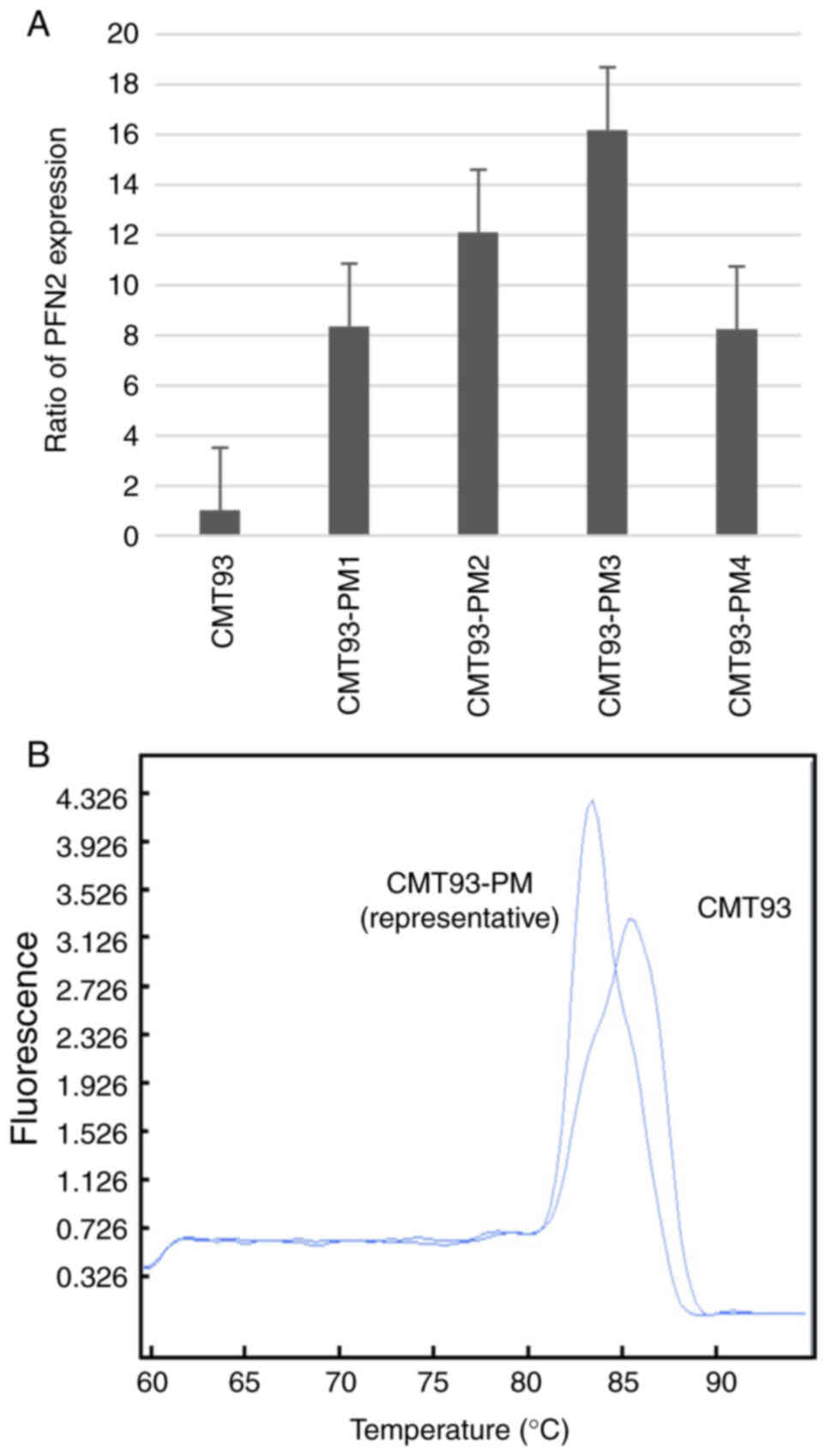

We focused on PFN2 because it showed the highest

level of overexpression in CMT93-PM1 cells (Table SI). We confirmed the differential

expression of PFN2 in the four cell lines of the CMT93-PM series

using RT-PCR. The PFN2 expression level was higher in

CMT93-PM1-4 cells than in CMT93 cells, however we could not confirm

a significant difference (Fig. 4A).

These two PFN2 isoforms have distinct functions in malignancy

(17). Two different melting

temperatures suggested the presence of two different types of

PFN2 following melting curve analysis (Fig. 4B). PFN2A and PFN2B isoforms are

splicing variants of PFN2 with different distributions

(18). The overall structure of

PFN2 is illustrated in Fig. 5

(18,19). We confirmed that PFN2A showed

significantly higher expression in CMT93-PM1-4 cell lines than in

CMT93 cells (P<0.01) (Fig. 6A).

As for PFN2B, we observed overexpression in CMT93-PM1-4 cell lines

and a significant difference in CMT93-PM2 cells (P<0.01).

Discussion

The molecular mechanisms underlying lung metastasis

in CRC have been extensively studied (8,9,12,13,20–23).

However, the number of patients included in these studies was

insufficient to obtain conclusive results owing to the

heterogeneity of metastatic tumors (8,12,21).

We can avoid the effects of tumor heterogeneity owing to varying

patient backgrounds (such as a history of smoking, obesity,

familial genomic problems, or other diseases, and previous

treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy) using

experimental animal models and cell lines. In a previous study, we

injected mouse rectal cancer cells into the tail vein and observed

lung metastases (13). We retrieved

metastatic tumors and established their cell lines. To the best of

our knowledge, this is the first cell line reported for the

treatment of metastatic lung colorectal cancer. While three studies

report the establishment or utilization of cell lines for liver

metastases (24–26), none have focused on the

establishment of cell lines for lung metastases. We found that the

lung surfactant SP-D suppressed lung metastasis by inhibiting the

epidermal growth factor receptor signaling using established cell

lines. Our previous study suggests that environmental factors might

affect lung metastasis in CRC (13). In this study, we conducted a global

gene expression analysis to reveal the background of lung

metastasis.

Initially, we confirmed the metastatic ability of

CMT93-PM1 cells. Metastatic sites were formed by numerous

homogeneous lesions in all the lungs. This form of lung metastasis

differs from that observed in clinical situations because most

human lung metastatic lesions form distinct nodules (27). However, this may be owing to the

high clonality of the tumor cells, immune evasion specialized in

the lung immune system, and the tail vein injection model. Multiple

mechanisms can influence this phenomenon, including the

upregulation of cell motility, cell adhesion, and invasion as well

as the downregulation of tumor suppressor genes and the immune

system. Therefore, we believe that employing technologies such as

microarrays and investigating changes in a wide range of genomes

are essential. This study provides new insights from this

perspective.

Microarray analysis revealed that 88 genes were

expressed with a fold change exceeding 10 times in CMT93-PM cells

compared to that in CMT93 cells. Cluster analysis revealed four

distinct clusters and subsequent enrichment analysis indicated that

these clusters exhibited distinctive features. Clusters A and B

consisting of genes upregulated in CMT93-PM1 cells were primarily

associated with cell adhesion, proliferation, and motility. These

functions are crucial for the formation of distant metastases,

consistent with the results of previous studies (28–30).

Notably, N-cadherin and VE-cadherin found within this cluster play

significant roles in cell adhesion and migration and exhibit strong

interactions with the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (31). The upregulation of N-cadherin

expression in CRC tissues is negatively correlated with E-cadherin

expression; furthermore, high N-cadherin expression promotes

proliferation and migration of CRC cells by inducing EMT (32). Six4 is another upregulated

gene in cluster A and B that activates Akt and triggers the

PI3K/Akt pathway (33). The

PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway is one of

the most pivotal intracellular pathways, serving as a master

regulator of cancer and enhancing cell growth and proliferation

(34). Additionally, VCAM1 in this

cluster promotes CRC invasion and metastasis by activating the EMT

(35).

In contrast, clusters C and D comprised

downregulated genes in CMT93-PM, and the roles of the genes in

these clusters were markedly different from those in clusters A and

B. Notably, a tumor suppressor gene [tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinase-3 (Timp3)] was found in these

clusters. TIMP3 plays various roles, one of which is the induction

of apoptosis through caspase-dependent and-independent pathways

(36). A decrease in Timp3

expression correlates with the malignant behavior of colorectal

cancer and TIMP3 overexpression results in reduced adhesion,

migration, and invasion of human CRC cells in vitro

(37). PAX6 was detected in

clusters C and D; it serves as a master control gene for the

development of the eyes, other sensory organs, certain neural and

epidermal tissues, and other homologous structures typically

derived from ectodermal tissues. PAX6 is a potential tumor

suppressor (38). Further

investigations are required to assess the relationship between PAX6

and colorectal cancer and the several differences between CMT93 and

CMT93-PM cells shown in this study.

We observed an overexpression of PFN2 in the

CMT93-PM series compared to that in the original CMT93 cells.

Furthermore, PFN2a and PFN2b splicing variants were

upregulated.

Profilins are actin-binding proteins that regulate

cell structure by controlling signal-dependent actin polymerization

(39). The profilin gene

family comprises two major isoforms: PFN1 and PFN2

(40). Mouse profilin I is

ubiquitously expressed in all tissues except skeletal muscle,

whereas profilin IIA is mainly expressed in neuronal tissues

(41). Thus, profilin I

appears to be a housekeeping gene that is important for vital

functions, whereas profilin II was later developed to serve

specific functions, mainly in the brain. PFN2 is alternately

spliced into PFN2a and 2b. Among these, PFN2a is the predominant

splice form (18,19) that is conserved across vertebrates,

including humans, mice, chickens, and cattle. Research on the

functions of PFN2a has primarily focused on cell migration and the

mammalian nervous system, including synaptic vesicle exocytosis and

neuronal excitability (42). The

relationship between PFN2 and lung, breast, and prostate cancers

was previously investigated (17,39,43,44).

PFN2 regulates growth by inhibiting nuclear localization of histone

deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) in lung cancer (43). It promotes the progression of small

cell lung cancer in vitro and in vivo and regulates

angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment through cancer-derived

exosomes (45).

Only two reports have described the role of PFN2 in

colorectal cancer and no previous study has described the

relationship between PFN2 isoforms and colorectal cancer. PFN2

promotes the metastatic potential and stemness of colorectal CSCs

by regulating EMT- and stemness-related proteins (45). These findings were consistent with

our results. In contrast, the loss of PFN2 contributes to

enhanced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis (46). Their observations are inconsistent

with our results, since they concluded that the loss of PFN2

exacerbates metastasis, leading them to insist that PFN2 inhibits

tumor metastasis. However, their study has several limitations.

First, although they concluded that PFN2 downregulation enhanced

cell migration, they compared two different cell lines: SW620 and

HCT116. Different cell lines have distinct genetic backgrounds in

addition to PFN2 expression. Therefore, comparisons between

different cell lines are not particularly informative. Second, a

retrovirus was used to transfect PFN2 into SW620 cells.

However, the retroviral vector method does not offer precise

control over the location of transfection and is often associated

with the activation of tumor-related genes. Third, in vitro

experiments were conducted, and the results were validated in

vivo. These factors could have contributed to the potential

differences between the results of their study and ours.

Our study has some limitations. First, we used a

single cell line (CMT93) as a model. Therefore, it is essential to

examine multiple cell lines to validate our results. Secondly, we

used the tail vein injection method with CMT93-PM and confirmed a

significant difference in metastatic function between CMT93-PM and

CMT93. However, the tail vein injection method has positive and

negative aspects for evaluating lung metastasis. In this method,

metastasis is initiated via tail vein injection, which mimics the

natural progression of colorectal cancer. After injection, tumor

cells were disseminated swiftly through systemic venous perfusion.

However, our experiment did not recapitulate metastasis in these

patients because the tumor cells were dispersed by proteinase

before injection. Thirdly, we used the cells derived from the

metastatic tumors in lungs, and the similarity of the established

cell lines with the original tumors, and the homogeneity of the

cells from the metastatic lesions were not be verified. Fourth, our

experiments are solely based on RNA and cDNA, lacking evidence of

protein expression levels for the two different types of PFN2. This

was due to the unavailability of the corresponding antibodies

commercially. Finally, we did not study the effects of PFN2

overexpression on cell behavior. Further investigations into the

function of PFN2 and the relationship between lung metastasis and

PFN2 are necessary to validate the clinical utility of our

findings. This validation may be achieved using pathological

materials and publicly available datasets. Additionally, the role

of each variant remains unclear. Studies on PFN2a and PFN2b will

provide deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms of lung

metastasis in CRC.

We established an in vitro lung metastasis

model using colorectal cancer cells and mice. Differential gene

expression analysis was used to identify genes associated with lung

metastasis. Thus, our model provides a unique platform to study

lung metastasis. The functional significance and clinical utility

of these two PFN2 isoforms should be considered in future

studies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Kaoru Hattori

(Department of Surgery, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo,

Japan) for their technical support and handling of the mice, Dr.

Shingo Akimoto (Department of Surgery, Keio University School of

Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) for their support during this study, and

Dr. Shinya Saito (Oncogene Research Unit/Cancer Prevention Unit,

Tochigi Cancer Center Research Institute, Utsunomiya, Japan) for

providing insightful instructions and support during the

experiments.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current

study are available from the GEO repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE252603).

GEO accession number is GSE252603. The rest of the data generated

in the present study may be requested from the corresponding

author.

Authors' contributions

NT and MT participated in the study design,

coordination, and drafting of manuscript. YT and YY performed the

experiments and acquired data. KS and KO participated in the study

design and performed statistical analyses. MT and TK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. HH, SF, TK, IO, and YK conceived

the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped

draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

study.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures were performed with the approval of

the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee at the Keio University

School of Medicine (approval no. 15006).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

DAVID

|

Database for Annotation, Visualization

and Integrated Discovery

|

|

HDAC1

|

histone deacetylase 1

|

|

PFN2

|

Profilin 2

|

|

RT-PCR

|

reverse transcription PCR

|

|

TIMP3

|

tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinase-3

|

References

|

1

|

Keum N and Giovannucci E: Global burden of

colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention

strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:713–732. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero

A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, Aguilar EA, Bardelli A, Benson A,

Bodoky G, et al: ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of

patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol.

27:1386–1422. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Muratore A, Zorzi D, Bouzari H, Amisano M,

Massucco P, Sperti E and Capussotti L: Asymptomatic colorectal

cancer with un-resectable liver metastases: Immediate colorectal

resection or up-front systemic chemotherapy? Ann Surg Oncol.

14:766–770. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Van Cutsem E, Nordlinger B, Adam R, Köhne

CH, Pozzo C, Poston G, Ychou M and Rougier P; European Colorectal

Metastases Treatment Group, : Towards a pan-European consensus on

the treatment of patients with colorectal liver metastases. Eur J

Cancer. 42:2212–2221. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Parnaby CN, Bailey W, Balasingam A,

Beckert L, Eglinton T, Fife J, Frizelle FA, Jeffery M and Watson

AJ: Pulmonary staging in colorectal cancer: A review. Colorectal

Dis. 14:660–670. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Watanabe T, Muro K, Ajioka Y, Hashiguchi

Y, Ito Y, Saito Y, Hamaguchi T, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, Ishihara S,

et al: Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR)

guidelines 2016 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin

Oncol. 23:1–34. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chandra R, Karalis JD, Liu C, Murimwa GZ,

Voth Park J, Heid CA, Reznik SI, Huang E, Minna JD and Brekken RA:

The colorectal cancer tumor microenvironment and its impact on

liver and lung metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 13:62062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang N, Di J, Wang Z, Gao P, Jiang B and

Su X: Genomic profiling of colorectal cancer with isolated lung

metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 20:2812020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yamamoto T, Kawada K, Itatani Y, Inamoto

S, Okamura R, Iwamoto M, Miyamoto E, Chen-Yoshikawa TF, Hirai H,

Hasegawa S, et al: Loss of SMAD4 promotes lung metastasis of

colorectal cancer by accumulation of CCR1+ tumor-associated

neutrophils through CCL15-CCR1 axis. Clin Cancer Res. 23:833–844.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Liu J, Shao Y, He Y, Ning K, Cui X, Liu F,

Wang Z and Li F: MORC2 promotes development of an aggressive

colorectal cancer phenotype through inhibition of NDRG1. Cancer

Sci. 110:135–146. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hu XT, Xing W, Zhao RS, Tan Y, Wu XF, Ao

LQ, Li Z, Yao MW, Yuan M, Guo W, et al: HDAC2 inhibits EMT-mediated

cancer metastasis by downregulating the long noncoding RNA H19 in

colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:2702020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kim SH, Choi SJ, Cho YB, Kang MW, Lee J,

Lee WY, Chun HK, Choi YS, Kim HK, Han J and Kim J: Differential

gene expression during colon-to-lung metastasis. Oncol Rep.

25:629–636. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tajima Y, Tsuruta M, Hasegawa H,

Okabayashi K, Ishida T, Yahagi M, Makino A, Koishikawa K, Akimoto

S, Sin DD and Kitagawa Y: Association of surfactant protein D with

pulmonary metastases from colon cancer. Oncol Lett. 20:3222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Kir J, Liu D,

Bryant D, Guo Y, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC and Lempicki RA:

David bioinformatics resources: Expanded annotation database and

novel algorithms to better extract biology from large gene lists.

Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W169–W175. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Huang R, Yuan DJ, Li S, Liang XS, Gao Y,

Lan XY, Qin HM, Ma YF, Xu GY, Schachner M, et al: NCAM regulates

temporal specification of neural progenitor cells via profilin2

during corticogenesis. J Cell Biol. 219:e2019021642020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mouneimne G, Hansen SD, Selfors LM, Petrak

L, Hickey MM, Gallegos LL, Simpson KJ, Lim J, Gertler FB, Hartwig

JH, et al: Differential remodeling of actin cytoskeleton

architecture by profilin isoforms leads to distinct effects on cell

migration and invasion. Cancer Cell. 22:615–630. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lambrechts A, Braun A, Jonckheere V,

Aszodi A, Lanier LM, Robbens J, Van Colen I, Vandekerckhove J,

Fässler R and Ampe C: Profilin II is alternatively spliced,

resulting in profilin isoforms that are differentially expressed

and have distinct biochemical properties. Mol Cell Biol.

20:8209–8219. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Di Nardo A, Gareus R, Kwiatkowski D and

Witke W: Alternative splicing of the mouse profilin II gene

generates functionally different profilin isoforms. J Cell Sci.

113:3795–3803. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang H, Fu W, Im JH, Zhou Z, Santoro SA,

Iyer V, DiPersio CM, Yu QC, Quaranta V, Al-Mehdi A and Muschel RJ:

Tumor cell alpha3beta1 integrin and vascular laminin-5 mediate

pulmonary arrest and metastasis. J Cell Biol. 164:935–941. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shu R, Xu Y, Tian Y, Zeng Y, Sun L, Gong

F, Lei Y, Wang K and Luo H: Differential expression profiles of

long noncoding RNA and mRNA in colorectal cancer tissues from

patients with lung metastasis. Mol Med Rep. 17:5666–5675.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tang L, Lei YY, Liu YJ, Tang B and Yang

SM: The expression of seven key genes can predict distant

metastasis of colorectal cancer to the liver or lung. J Dig Dis.

21:639–649. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dai W, Guo C, Wang Y, Li Y, Xie R, Wu J,

Yao B, Xie D, He L, Li Y, et al: Identification of hub genes and

pathways in lung metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer.

23:3232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lu M, Zessin AS, Glover W and Hsu DS:

Activation of the mTOR pathway by oxaliplatin in the treatment of

colorectal cancer liver metastasis. PLoS One. 12:e01694392017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li LN, Zhang HD, Yuan SJ, Tian ZY and Sun

ZX: Establishment and characterization of a novel human colorectal

cancer cell line (CLY) metastasizing spontaneously to the liver in

nude mice. Oncol Rep. 17:835–840. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Govaert KM, Emmink BL, Nijkamp MW, Cheung

ZJ, Steller EJ, Fatrai S, de Bruijn MT, Kranenburg O and Rinkes IH:

Hypoxia after liver surgery imposes an aggressive cancer stem cell

phenotype on residual tumor cells. Ann Surg. 259:750–759. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Salah S, Ardissone F, Gonzalez M, Gervaz

P, Riquet M, Watanabe K, Zabaleta J, Al-Rimawi D, Toubasi S, Massad

E, et al: Pulmonary metastasectomy in colorectal cancer patients

with previously resected liver metastasis: Pooled analysis. Ann

Surg Oncol. 22:1844–1850. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang JY, Sun J, Huang MY, Wang YS, Hou MF,

Sun Y, He H, Krishna N, Chiu SJ, Lin S, et al: STIM1 overexpression

promotes colorectal cancer progression, cell motility and COX-2

expression. Oncogene. 34:4358–4367. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jackstadt R, Röh S, Neumann J, Jung P,

Hoffmann R, Horst D, Berens C, Bornkamm GW, Kirchner T, Menssen A

and Hermeking H: AP4 is a mediator of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Exp Med.

210:1331–1350. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Eckey M, Kuphal S, Straub T, Rümmele P,

Kremmer E, Bosserhoff AK and Becker PB: Nucleosome remodeler SNF2L

suppresses cell proliferation and migration and attenuates Wnt

signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 32:2359–2371. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Katoh M: Multi-layered prevention and

treatment of chronic inflammation, organ fibrosis and cancer

associated with canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling activation

(Review). Int J Mol Med. 42:713–725. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yan X, Yan L, Liu S, Shan Z, Tian Y and

Jin Z: N-cadherin, a novel prognostic biomarker, drives malignant

progression of colorectal cancer. Mol Med Rep. 12:2999–3006. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sun X, Hu F, Hou Z, Chen Q, Lan J, Luo X,

Wang G, Hu J and Cao Z: SIX4 activates Akt and promotes tumor

angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 383:1114952019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yang J, Nie J, Ma X, Wei Y, Peng Y and Wei

X: Targeting PI3K in cancer: Mechanisms and advances in clinical

trials. Mol Cancer. 18:262019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang D, Bi J, Liang Q, Wang S, Zhang L,

Han F, Li S, Qiu B, Fan X, Chen W, et al: VCAM1 promotes tumor cell

invasion and metastasis by inducing EMT and transendothelial

migration in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 10:10662020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kallio JP, Hopkins-Donaldson S, Baker AH

and Kähäri VM: TIMP-3 promotes apoptosis in nonadherent small cell

lung carcinoma cells lacking functional death receptor pathway. Int

J Cancer. 128:991–996. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lin H, Zhang Y, Wang H, Xu D, Meng X, Shao

Y, Lin C, Ye Y, Qian H and Wang S: Tissue inhibitor of

metalloproteinases-3 transfer suppresses malignant behaviors of

colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 19:845–851. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kiselev Y, Andersen S, Johannessen C,

Fjukstad B, Olsen KS, Stenvold H, Al-Saad S, Donnem T, Richardsen

E, Bremnes RM and Busund LT: Transcription factor PAX6 as a novel

prognostic factor and putative tumour suppressor in non-small cell

lung cancer. Sci Rep. 8:50592018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ma CY, Zhang CP, Zhong LP, Pan HY, Chen

WT, Wang LZ, Andrew OW, Ji T and Han W: Decreased expression of

profilin 2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma and its

clinicopathological implications. Oncol Rep. 26:813–823.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Jeong DH, Choi YN, Seo TW, Lee JS and Yoo

SJ: Ubiquitin-proteasome dependent regulation of Profilin2 (Pfn2)

by a cellular inhibitor of apoptotic protein 1 (cIAP1). Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 506:423–428. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Witke W, Podtelejnikov AV, Di Nardo A,

Sutherland JD, Gurniak CB, Dotti C and Mann M: In mouse brain

profilin I and profilin II associate with regulators of the

endocytic pathway and actin assembly. EMBO J. 17:967–976. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Boyl PP, Di Nardo A, Mulle C,

Sassoè-Pognetto M, Panzanelli P, Mele A, Kneussel M, Costantini V,

Perlas E, Massimi M, et al: Profilin2 contributes to synaptic

vesicle exocytosis, neuronal excitability, and novelty-seeking

behavior. EMBO J. 26:2991–3002. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tang YN, Ding WQ, Guo XJ, Yuan XW, Wang DM

and Song JG: Epigenetic regulation of Smad2 and Smad3 by profilin-2

promotes lung cancer growth and metastasis. Nat Commun. 6:82302015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Obinata D, Funakoshi D, Takayama K, Hara

M, Niranjan B, Teng L, Lawrence MG, Taylor RA, Risbridger GP,

Suzuki Y, et al: OCT1-target neural gene PFN2 promotes tumor growth

in androgen receptor-negative prostate cancer. Sci Rep.

12:60942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Cao Q, Liu Y, Wu Y, Hu C, Sun L, Wang J,

Li C, Guo M, Liu X, Lv J, et al: Profilin 2 promotes growth,

metastasis, and angiogenesis of small cell lung cancer through

cancer-derived exosomes. Aging (Albany NY). 12:25981–25999. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhang H, Yang W, Yan J, Zhou K, Wan B, Shi

P, Chen Y, He S and Li D: Loss of profilin 2 contributes to

enhanced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of

colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 53:1118–1128. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|