Introduction

Serum creatine kinase (s-CK) is one of the routine

blood tests in patients with cancer. s-CK is an enzyme consumed in

energy metabolism in various tissues and has been reported to be

involved in cell division and the immune system (1,2).

Importantly, studies have reported low s-CK levels as a poor

prognostic factor in esophageal (3), gastric (4), breast (5), and lung cancers (6,7).

The mechanisms of low s-CK activity in patients with

cancer are not fully understood. Tumor cells may consume s-CK to

generate energy needed for increased proliferation, leading to a

decline in s-CK levels. Cancer-related inflammation and cachexia

may also lead to the loss of muscle mass, and muscle wasting in

patients with cancer is considered to impact the decrease in s-CK

levels.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most

common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related

deaths (8). The prognosis of

patients with HCC is unsatisfactory because of the high incidence

of tumor recurrence and distant metastasis (9). Early detection of HCC recurrence is

associated with improved prognosis due to the better response of

smaller tumors to potentially curative treatments such as liver

resection, radiofrequency ablation, and transcatheter arterial

chemoembolization (10–12). Therefore, the development of

biomarkers that can predict HCC recurrence is important (13). s-CK has long been known to be highly

active in cancers, including HCC, suggesting its potential as a

prognostic factor (14). However,

no report to date has demonstrated the clinicopathologic and

prognostic significance of s-CK in patients with HCC.

Based on our hypothesis that low s-CK level was

associated with adverse outcomes in HCC, we aimed to evaluate the

prognostic significance of preoperative s-CK levels in patients

with HCC.

Materials and methods

Study population

This was a retrospective study including 163

patients (127 male and 36 female patients) with a median age of 69

(range, 40–88) who were diagnosed with HCC and underwent radical

liver resection between January 2004 and December 2021 in Toho

University Omori Medical Center. This study protocol was approved

by the Ethics Committee of Toho University Omori Medical Center

(The approval number is M22223, the approval date is November 30,

2022.) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. Information about the study was disclosed on the

institutional website and the potential participants were given the

opportunity to opt-out.

Study design

The following clinicopathologic factors were

included to evaluate their association with preoperative and

postoperative s-CK levels: age, sex, presence of cirrhosis, tumor

size, stage [Japanese Classification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma;

2019 (The 6th Edition)], indocyanine green retention (ICG) rate at

15 min, white blood cell, platelet counts, levels of α-fetoprotein

(AFP) and levels of protein induced by vitamin K absence or

antagonist-II (PIVKA-II).

Preoperative s-CK levels measured during routine

blood tests within seven days before surgery and postoperative s-CK

levels measured at discharge or at one-month follow-up after

surgery were included in the present study. Cut-off preoperative

and postoperative s-CK levels were determined using receiver

operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis, with death due to

any case as the dependent variable. Then, patients were categorized

into those with high and low preoperative s-CK levels based on the

cutoff preoperative s-CK level to evaluate the association of

preoperative s-CK levels with clinicopathologic factors, overall

survival (OS), and recurrence-free survival (RFS).

In the present study, OS was defined as the interval

from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up.

RFS was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to the

date of known recurrence.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test (unpaired) and Fisher's exact

probability tests were used for two-group comparisons. OS and RFS

were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences

between the groups were evaluated using the log-rank test.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox

proportional hazards regression. All statistical analyses were

performed using EZR (15). A

two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered to denote statistical

significance.

Results

Patient categorization according to

preoperative s-CK levels

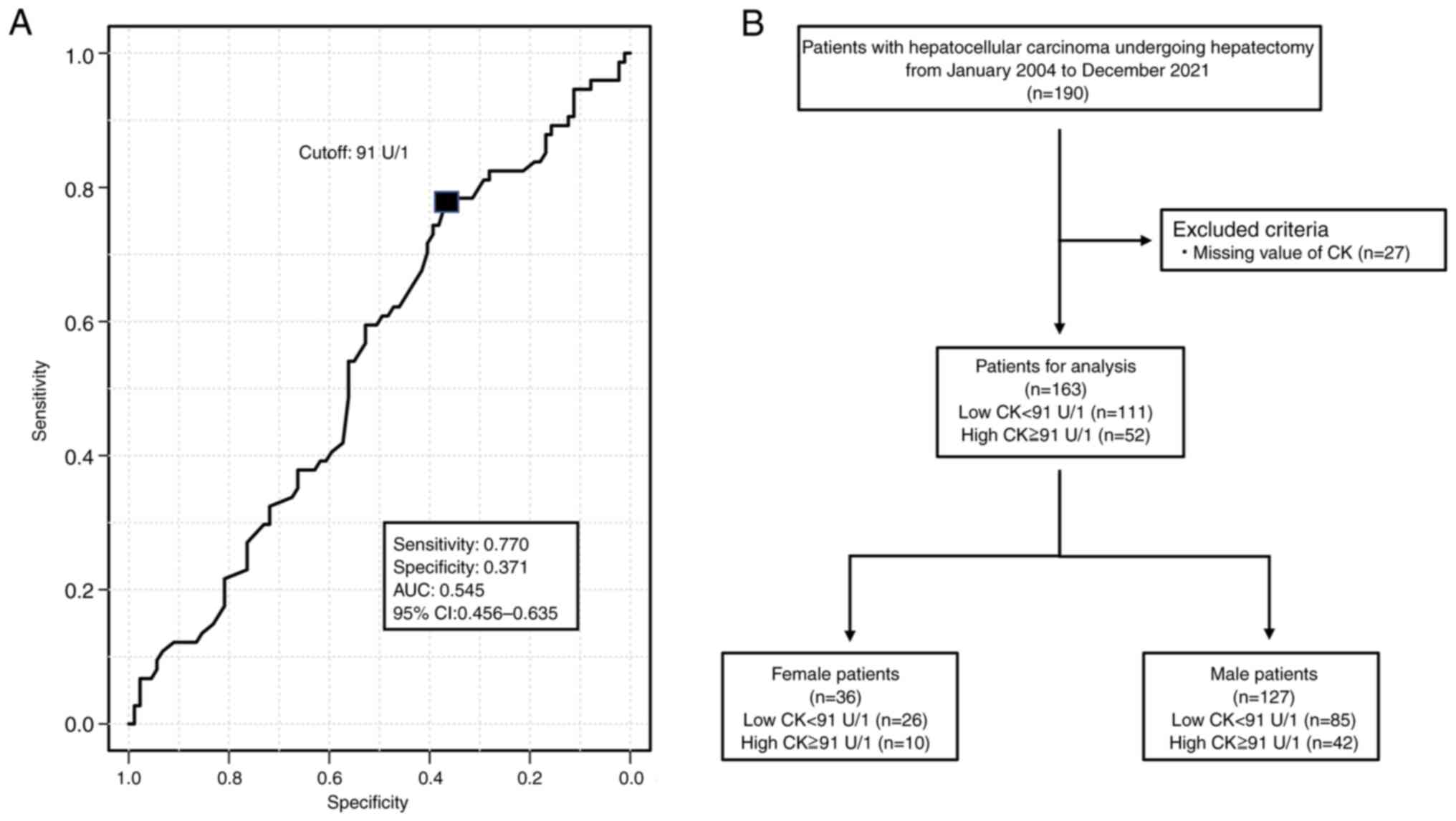

Based on the cutoff preoperative s-CK level of 91

U/l according to the ROC analysis (Fig.

1A), the 127 males were divided into the high CK group (n=85)

and low CK group (n=42). The 36 females were divided into the high

CK group (n=26) and the low CK group (n=10) (Fig. 1B).

Association of preoperative s-CK levels with

clinicopathologic factors.

Four patients did not undergo the ICG test because

of allergy to the contrast medium. No clinicopathological factors

were significantly associated with the rate of patients with low

preoperative s-CK levels (Table

I).

| Table I.Univariate analysis of

clinicopathological factors of the low and high preoperative

creatine kinase groups in patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma. |

Table I.

Univariate analysis of

clinicopathological factors of the low and high preoperative

creatine kinase groups in patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma.

| Variables | Groups | No. of patients | Low preoperative

(n=163) creatine kinase, <91 U/l (n=111) | High preoperative

creatine kinase, ≥91 U/l (n=52) | P-valuea |

|---|

| Sex | Female | 36 | 26 | 10 | 0.686 |

|

| Male | 127 | 85 | 42 |

|

| Age, years | <65 | 55 | 35 | 20 | 0.477 |

|

| ≥65 | 108 | 76 | 32 |

|

| Cirrhotic liver | Negative | 62 | 41 | 21 | 0.730 |

|

| Positive | 101 | 70 | 31 |

|

| Tumor size, mm | <20 | 42 | 31 | 11 | 0.443 |

|

| ≥20 | 121 | 80 | 41 |

|

| Stage | I/II | 111 | 71 | 40 | 0.108 |

|

| III/IV | 52 | 40 | 12 |

|

| ICG R15, % | <10 | 73 | 51 | 22 | 0.733 |

|

| ≥10 | 86 | 57 | 29 |

|

| White blood cell,

/µl | <8,000 | 154 | 105 | 49 | 1.000 |

|

| ≥8,000 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

|

| Platelet, /µl | <150,000 | 69 | 49 | 20 | 0.614 |

|

| ≥150,000 | 94 | 62 | 32 |

|

| AFP, ng/ml | Negative | 105 | 72 | 33 | 0.863 |

|

| Positive | 58 | 39 | 19 |

|

| PIVKA-II, mAU/ml | Negative | 80 | 54 | 26 | 1.000 |

|

| Positive | 83 | 57 | 26 |

|

Comparison of OS between patients with

low and high preoperative s-CK levels

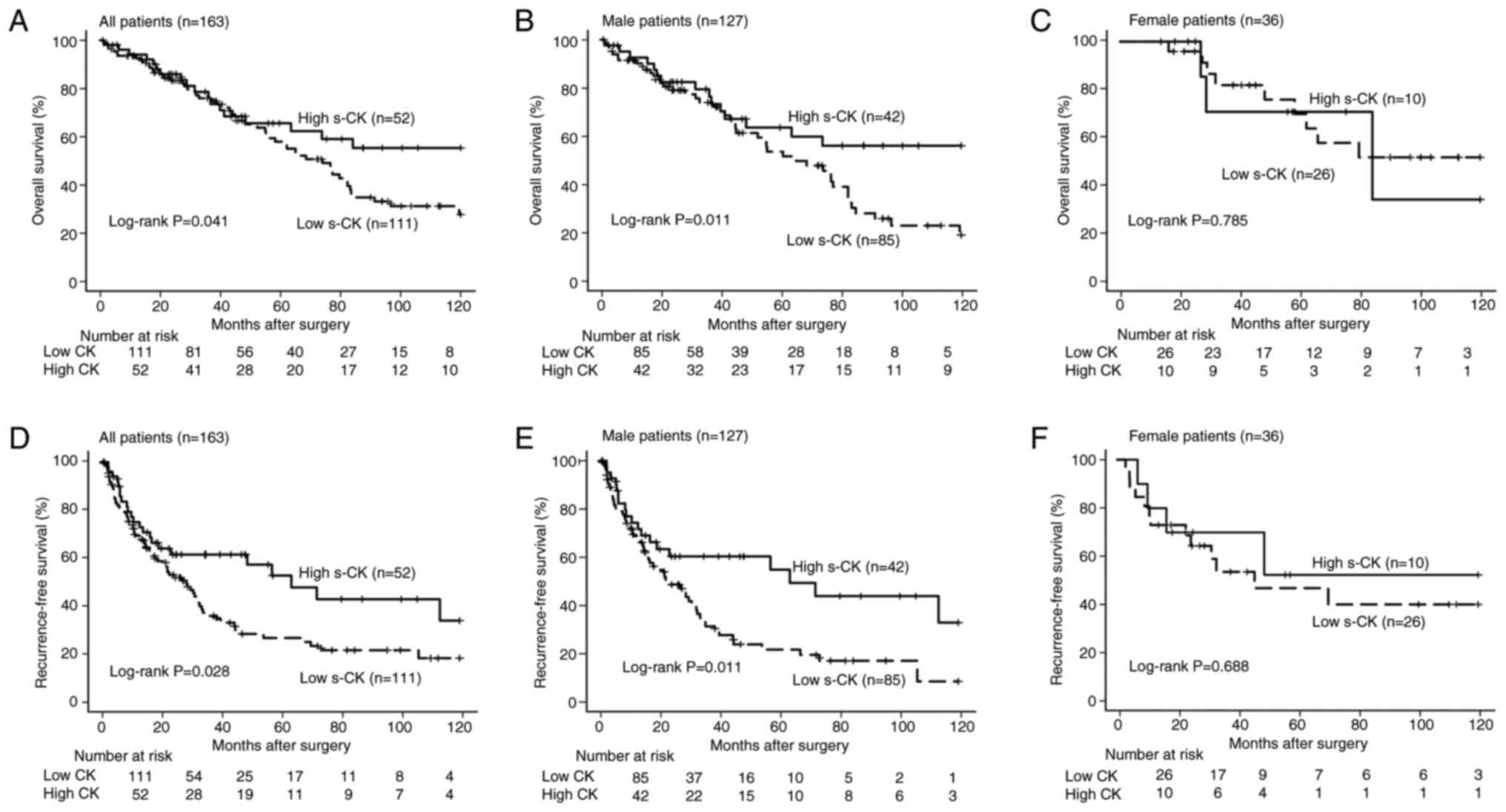

In the overall cohort, the OS was significantly

worse in the low preoperative s-CK group than in the high

preoperative s-CK group (P=0.043, Fig.

2A). Similarly, the OS was significantly worse in the low

preoperative s-CK group than in the high preoperative s-CK group

among the male patients (P=0.011, Fig.

2B). However, a significant difference in OS was not found

between the female patients with low and high preoperative s-CK

levels (P=0.785, Fig. 2C).

Univariate analysis revealed that the OS was

significantly worse in patients with low preoperative s-CK levels,

those aged over 65 years, those with an ICG retention rate of ≥10%

at 15 min, and those with high α-fetoprotein and PIVKA-II levels

compared to others (P<0.05, Table

II). Multivariate analysis revealed that a low preoperative

s-CK level, ICG retention rate of ≥10% at 15 min, and high PIVKA-II

level were independent poor prognostic factors for OS (P<0.05,

Table II).

| Table II.Univariate and multivariate analysis

of clinicopathological factors for predicting overall survival of

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of clinicopathological factors for predicting overall survival of

patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | No. patients

(n=163) | Hazard ratio (95%

confidence interval) |

P-valuea | Hazard ratio (95%

confidence interval) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male/Female | 127/36 | 1.756

(0.946–3.259) | 0.074 |

|

|

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥65/<65 | 108/55 | 1.744

(1.031–2.950) | 0.038 | 1.502

(0.884–2.552) | 0.133 |

| Cirrhotic

liver |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive/negative | 101/62 | 0.897

(0.559–1.437) | 0.650 |

|

|

| Tumor size, mm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥20/<20 | 121/42 | 1.262

(0.724–2.198) | 0.412 |

|

|

| Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

| I

II/III IV | 111/52 | 0.781

(0.483–1.263) | 0.313 |

|

|

| ICG R15, % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥10/<10 | 86/73 | 1.996

(1.223–3.258) | 0.005 | 2.077

(1.264–3.414) | 0.004 |

| White blood cell,

/µl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥8,000/<8,000 | 9/154 | 0.618

(0.195–1.969) | 0.416 |

|

|

| Platelet, /µl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥150,000/<150,000 | 94/69 |

1.221(0.769–1.936) | 0.397 |

|

|

| AFP, ng/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive/negative | 58/105 | 1.668

(1.053–2.643) | 0.029 | 1.336

(0.819–2.179) | 0.247 |

| PIVKA-II,

mAU/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive/negative | 83/80 | 2.389

(1.473–3.875) | 0.001 | 2.115

(1.263–3.541) | 0.004 |

| Preoperative serum

creatine kinase, U/l |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<91/≥91 | 111/52 | 1.739

(1.017–2.973) | 0.043 | 1.946

(1.115–3.397) | 0.019 |

Comparison of RFS between patients

with low and high preoperative s-CK levels

The RFS of the low preoperative s-CK group was

significantly worse than that of the high preoperative s-CK group

in the overall cohort (P=0.028, Fig.

2D) and among the male patients (P=0.011, Fig. 2E). Similar to our findings regarding

OS, the RFS did not significantly differ between the female

patients with low and high preoperative s-CK levels (P=0.688,

Fig. 2F).

Univariate analysis revealed that the RFS was

significantly worse in patients with low preoperative s-CK levels,

those with an ICG retention rate of ≥10% at 15 min, and those with

high PIVKA-II levels compared to others (P<0.05, Table III). Multivariate analysis

revealed that low preoperative s-CK level, an ICG retention rate of

≥10% at 15 min, and high PIVKA-II level were independent poor

prognostic factors for RFS (P<0.05, Table III).

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate analysis

of clinicopathological factors for predicting recurrence-free

survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

of clinicopathological factors for predicting recurrence-free

survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | No. patients

(n=163) | Hazard ratio (95%

confidence interval) |

P-valuea | Hazard ratio (95%

confidence interval) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male/female | 127/36 | 1.651

(0.974–2.798) | 0.063 |

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥65/<65 | 108/55 | 1.127

(0.732–1.737) | 0.587 |

|

|

| Cirrhotic

liver |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive/negative | 101/62 | 1.356

(0.879–2.091) | 0.587 |

|

|

| Tumor size, mm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥20/<20 | 121/42 | 1.085

(0.676–1.739) | 0.736 |

|

|

| Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

| I

II/III IV | 111/52 | 0.875

(0.566–1.354) | 0.549 |

|

|

| ICG R15, % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥10/<10 | 86/73 | 1.514

(0.991–2.312) | 0.050 | 1.625

(1.061–2.491) | 0.026 |

| White blood cell,

/µl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥8,000/<8,000 | 9/154 | 0.803

(0.326–1.979) | 0.634 |

|

|

| Platelet, /µl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

≥150,000/<150,000 | 94/69 | 1.452

(0.965–2.184) | 0.073 |

|

|

| AFP, ng/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive/Negative | 58/105 | 1.295

0.850–1.972) | 0.228 |

|

|

| PIVKA-II,

mAU/ml |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive/Negative | 83/80 | 1.746

(1.155–2.639) | 0.008 | 1.802

(1.180–2.752) | 0.006 |

| Preoperative serum

creatine kinase, U/l |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<91/≥91 | 111/52 | 1.689

(1.053–2.709) | 0.029 | 1.843

(1.122–3.000) | 0.014 |

Discussion

In the present study, although preoperative s-CK

level was not associated with any clinicopathological factors, low

preoperative s-CK level was an independent risk factor for poor OS

and RFS in patients with HCC.

In the previous reports, cutoff values have varied

by cancer type, and there seems to be no unified view regarding how

the cutoff should be determined. The cutoff values have varied by

the median value (3), the ROC curve

(4), the mean value (5), and the upper or lower limit of normal

(6). Our study first examined

cutoff values based on the ROC curve, median, and quartile. Among

them, only the cutoff value based on the ROC curve showed

significant differences both in the results of log-rank tests for

OS and RFS and the results of univariate and multivariate analyses

of prognostic factors for OS and RFS. The area under the curve in

this ROC curve is 0.545, indicating low accuracy. Although this is

a weak point of our study, further discussion of the cutoff value

for s-CK in HCC is difficult because no other reports showed it. In

the future, we plan to conduct a multi-center collaborative study

by recruiting other facilities that agree with this paper's

objectives.

Regarding to the clinicopathological significance of

s-CK level, low s-CK level was related to the tumor progression in

other cancers. Reduction of s-CK level was found in the deep tumor

in esophageal (3) and gastric

cancer (4), large tumor in breast

cancer (5), and bone and lymph node

metastases in lung cancer (7).

However, in the present study on HCC, preoperative s-CK levels were

not associated with any of the analyzed clinicopathologic factors.

These findings suggest that clinicopathologic factors might have

limited association with prognosis in HCC and that the malignancy

potential of the tumor itself might be related to prognosis.

Regarding to the OS, the low and high s-CK groups

showed similar survival curves until five years after surgery.

However, the survival difference appeared at five years after

surgery in OS. This observation was not previously reported in

other cancer types and might be unique to HCC. This difference

might be due to the availability of various treatment options for

HCC recurrence, including repeat liver resection, radiofrequency

ablation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, chemotherapy,

and immune checkpoint inhibitors, which might have contributed to

improved survival after recurrence for up to five years. Although

the tendency of RFS was similar to that of OS, the differences in

RFS between the two groups were obvious even within five years. The

RFS was significantly different between the patients with low and

high preoperative s-CK levels five years after liver resection.

The potential role of estrogen should be considered

regarding the observed sex difference in the impact of low

preoperative s-CK levels on OS. In females, estrogen, a major

female hormone, stabilizes skeletal fascia by suppressing the

release of s-CK into the bloodstream (16,17).

Therefore, s-CK levels are lower in females than in males, and the

difference in OS between the female patients with low and high s-CK

levels could have been similar to the difference in OS observed

between the male patients in the absence of estrogen's effect on

s-CK levels. Because our study included only 36 females, prognostic

factors were not examined separately for males and females.

Estrogen suppression of s-CK release may have the same effect as in

gastric cancer (4), but the small

number of female cases makes it difficult to draw a definite

conclusion. Further research is necessary to determine if s-CK is a

potential prognostic factor in females.

Our multivariate analysis also revealed that low

preoperative s-CK level was an independent poor risk factor OS and

RFS, similar to that observed in esophageal (3) and gastric cancers (4). Although low s-CK levels were

associated with disease progression in esophageal and gastric

cancers, a similar finding was not previously reported in HCC. We

speculate that tumor volume might be associated with s-CK

consumption in esophageal and gastric cancers. However, we did not

observe an association between tumor volume and low s-CK levels in

the current cohort of patients with HCC and low s-CK levels in HCC

might strongly reflect malignant potential. It was suggested that

the higher the cancer cells consume s-CK, the higher the malignant

potential.

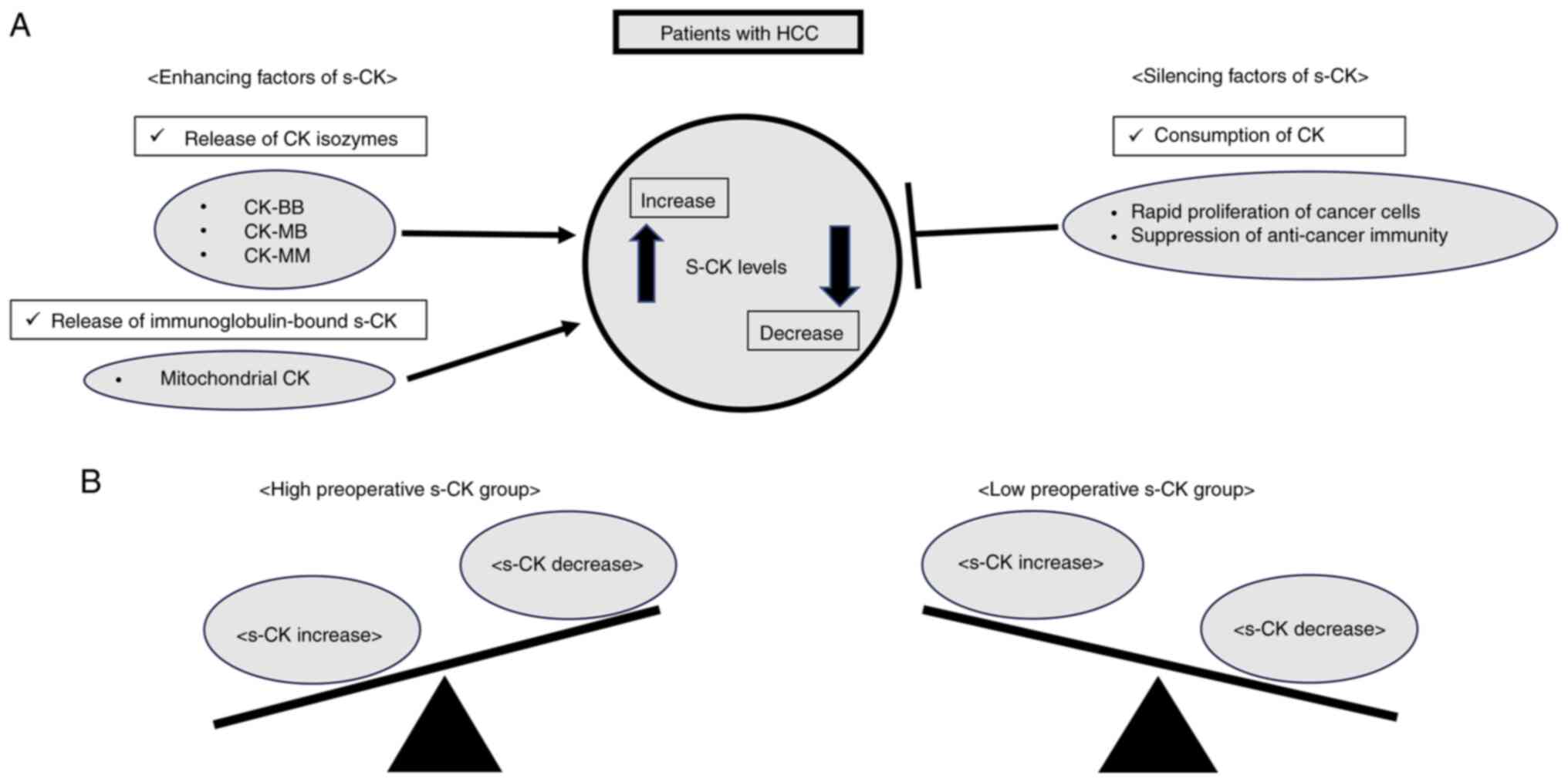

Based on our present study, in the patients with

HCC, various factors are supposed to effect s-CK levels. There were

several factors that increased or decreased s-CK in the patients

with HCC (Fig. 3A). According to

Yan YB's report (1), enhancing

factors of s-CK include CK isozymes (e.g., CK-BB, CK-MB, CK-MM) and

immunoglobulin-bound forms (e.g., mitochondrial CK), which may be

associated with s-CK increase. On the other hand, silencing factors

of s-CK include rapid cancer proliferation and decreased

anti-cancer immunity, which may be associated with s-CK decrease.

We think that the rapid proliferation of cancer cells and the

suppression of anti-cancer immunity could be explained by cancer

cells' enhancement of creatine metabolism (2). Highly active cancer cells need energy

for rapid proliferation. Therefore, we assume cancer cells obtain

energy by consuming s-CK and converting adenosine triphosphate to

adenosine diphosphate. T cells play an essential role in

anti-cancer defense. And creatine metabolism has the function of

anti-tumor T-cell immunity (2). In

rapidly proliferated cancer cells, T cells and cancer cells compete

for creatine kinase in the blood. As a result, T cell production is

reduced, leading to decreased anti-tumor immunity. The preoperative

high s-CK group is a condition where CK increase exceeds decrease,

and the preoperative low s-CK group is a condition where CK

decrease exceeds increase (Fig.

3B). Therefore, the preoperative low s-CK group may reflect a

highly malignant potential of HCC.

The present study has several limitations. First,

since this was the first study to evaluate the association between

s-CK levels and HCC, a cut-off value for S-CK was determined using

a test cohort of all patients. We expect further reports from other

centers on the validation cohort regarding the significance of the

cut-off value in the future. Second, the sample size was relatively

small in this single-center study and future studies with larger

cohort sizes are warranted to confirm the current study findings.

Third, CK has three isozymes: CK-MM, CK-MB, and CK-BB. A previous

study reported that the CK-MB/total CK ratio was useful in

detecting pancreatic adenocarcinoma (18), suggesting that the determination of

all isozymes might be considered to more accurately evaluate the

role of CK as a prognostic factor compared to total s-CK levels.

Unfortunately, the retrospective study design precluded the

determination of the levels of all three isozymes. Fourth,

underlying diseases such as dermatomyositis and cardiovascular

disease, which could potentially impact preoperative s-CK levels,

were not excluded. We aim to resolve these limitations in the

future through a multicenter study.

In conclusion, low preoperative s-CK level was an

independent risk factor for poor OS and RFS after surgery in

patients with HCC. Our present study showed promising early

findings regarding the association between low s-CK levels and poor

OS in HCC. Further study with a larger sample size is required to

make the findings more statistically reliable. Long-term follow-up

of patients is crucial to ensure the impact of low s-CK levels on

poor OS and RFS. Rigorous statistical analysis will ensure the

strength of the conclusions drawn. It is also important to compare

the prognostic value of low s-CK levels with existing standard

treatments to establish their relative importance. These efforts

will help determine whether low s-CK levels can be reliably used as

a prognostic biomarker in the clinical management of HCC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Matsuura

H. and Mr. Ota T. (Department of Medical Information Center, Toho

University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) for collecting

laboratory data.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YM and HS designed this study. YM, YO, RO, YI, KK,

JI, TM, MT and KF were involved in its conception, design and data

collection. YM, RO and YI confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. YM and HS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Toho University Omori Medical Center (approval no.

M22223; November 2022), and we provided means of opting out for

patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

s-CK

|

serum creatine kinase

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

ICG

|

indocyanine green retention

|

|

AFP

|

α-fetoprotein

|

|

PIVKA-II

|

vitamin K absence or antagonist-II

|

|

ROC

|

receiver operating characteristic

curve

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

RFS

|

recurrence-free survival

|

References

|

1

|

Yan YB: Creatine kinase in cell cycle

regulation and cancer. Amino Acids. 48:1775–1784. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kazak L and Cohen P: Creatine metabolism:

Energy homeostasis, immunity and cancer biology. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 16:421–436. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Murayama K, Suzuki T, Yajima S, Oshima Y,

Nanami T, Shiratori F and Shimada H: Preoperative low serum

creatine kinase is associated with poor overall survival in the

male patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus.

12:105–112. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yamazaki N, Oshima Y, Shiratori F, Nanami

T, Suzuki T, Yajima S, Funahashi K and Shimada H: Prognostic

significance of preoperative low serum creatine kinase levels in

gastric cancer. Surg Today. 52:1551–1559. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pan H, Xia K, Zhou W, Xue J, Liang X, Chen

L, Wu N, Liang M, Wu D, Ling L, et al: Low serum creatine kinase

levels in breast cancer patients: A case-control study. PLoS One.

8:e621122013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Liu L, He Y, Ge G, Li L, Zhou P, Zhu Y,

Tang H, Huang Y, Li W and Zhang: Lactate dehydrogenase and creatine

kinase as poor prognostic factors in lung cancer: A retrospective

observational study. PLoS One. 12:e01821682017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Takamori S, Toyokawa G, Shimokawa M,

Kinoshita F, Kazuma Y, Matsubara T, Haratake N, Akamine T, Hirai F,

Tagawa T, et al: A novel prognostic marker in patients with

non-small cell lung cancer: Musculo- immuno-nutritional score

calculated by controlling nutritional status and creatine kinase. J

Thorac Dis. 11:927–935. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Forner A, Reig M and Bruix J:

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 391:1301–1314. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Qin LX and Tang ZY: The prognostic

significance of clinical and pathological features in

hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 8:193–199. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Befeler AS and Di Bisceglie AM:

Hepatocellular carcinoma: Diagnosis and treatment.

Gastroenterology. 122:1609–1610. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ho EY, Cozen ML, Shen H, Lerrigo R,

Trimble E, Ryan JC, Covera CU and Monto A; HOVAS Group

(Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treatment Outcome at VA San Francisco), :

Expanded use of aggressive therapies improves survival in early and

intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 16:758–767.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Liu Y, Shi M, Chen S, Wan W, Shen L, Shen

B, Qui H, Cao F, Wu Y, Huang T, et al: Intermediate stage

hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison of the value of

inflammation-based scores in predicting progression-free survival

of patients receiving transarterial chemoembolization. J Cancer Res

Ther. 17:740–748. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yanagaki M, Haruki K, Taniai T, Igarashi

Y, Yasuda J, Furukawa K, Onda S, Shirai Y and Tsunematsu M: The

significance of osteosarcopenia as a predictor of the long-term

outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection. J

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 30:453–461. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kanemitsu F, Kawanishi I, Mizushima J and

Okigaki T: Mitochondrial creatine kinase as a tumor-associated

marker. Clin Chim Acta. 138:175–183. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Neal RC, Ferdinand KC, Ycas J and Miller

E: Relationship of ethnic origin, gender, and age to blood creatine

kinase levels. Am J Med. 122:73–78. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hackney AC, Kallman AL and Ağgön E: Female

sex hormones and the recovery from: Menstrual cycle phase affects

responses. Biomed Hum Kinet. 11:87–89. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen C, Lin X, Lin R, Huang H and Lu F: A

high serum creatine kinase (CK)-MB-to-total-CK ratio in patients

with pancreatic cancer: A novel application of a traditional marker

in predicting malignancy of pancreatic masses? World J Surg Oncol.

21:132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|