Introduction

Osteosarcoma is a mesenchymal tumor of the bones,

typically occurring in the long bones of the extremities.

Osteosarcoma in the long bones of the extremities accounts for

~80–90% of all cases of osteosarcoma (1). By contrast, two of the rarest sites

for this disease to be diagnosed are the hand and the foot,

representing ~1% of all diagnosed osteosarcomas (2–4). The

rarity of osteosarcoma of the hand and foot has led to frequent

misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis or inappropriate treatment of

patients, which can have fatal consequences (5). The uncommon occurrence of osteosarcoma

of the hand and foot, its similar appearance to benign lesions and

the general lack of awareness of this disease may result in

physicians not immediately suspecting osteosarcoma when evaluating

patients. Delays in diagnosing and treating peripheral osteosarcoma

can have a negative impact on patient outcomes. These delays may

reduce treatment options and diminish the possibility of

limb-sparing procedures, potentially affecting the overall

prognosis and quality of life of patients. Previous studies have

raised contradictions about the prognosis and treatment of hand and

foot osteosarcoma when compared with that at other common sites

(6). This condition primarily

affects adolescents and young adults, with the majority of cases

occurring between the ages of 10 and 25. However, it can also

affect older adults (7). Outcomes

for this disease typically have a favorable prognosis, but there

are currently few reports on hand and foot osteosarcoma (8). In the hand and foot, salvaging the

limb is typically the treatment of choice, and with the use of

chemotherapy (CHT), 60–65% of patients with osteosarcoma can be

cured without amputation (1,9).

Currently, there is a lack of comprehensive

understanding and published data regarding the diagnosis, treatment

and outcomes of osteosarcoma in the hand and foot, as these cases

represent ~1% of all osteosarcomas. Due to its rarity, misdiagnosis

and treatment delays are common, yet detailed reviews and analyses

of such cases are limited. To build upon the limited existing

literature, the present study conducted a series of single-center

case reports on a group of patients treated at the Masaryk Memorial

Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center (Brno, Czechia). The present

retrospective cohort study aimed to review and analyze cases of

osteosarcoma located in the hand and foot. Furthermore, certain

patient cases were described to highlight key educational points,

including unexpected outcomes, misdiagnoses and failed

interventions. These case reports may offer valuable insights into

treatment efficacy, diagnostic challenges and rare complications of

hand and foot osteosarcoma. By identifying common misdiagnoses and

raising awareness of the rarity of hand and foot osteosarcoma, the

present study may contribute to more accurate and timely diagnoses,

preventing delays in treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient

selection

The present retrospective study selected data from

patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma of the hand and foot. Between

January 2007 and January 2019, 11 patients were treated at the

Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center, with 5 cases

involving the hand and 6 involving the foot (Table I).

| Table I.Patient demographics. |

Table I.

Patient demographics.

| Demographic | Value |

|---|

| Total number of

patients, n | 11 |

| Mean age at inclusion

(SD), years | 30.9 (16.74) |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

| Male | 6 (54.5) |

|

Female | 5 (45.5) |

| Mean follow-up period

(SD), months | 90.36 (66.14) |

| Comorbidities, n

(%) |

|

|

Yes | 2 (18.2) |

| No | 9 (81.8) |

| Mean symptom

duration (SD), months | 8.91 (3.80) |

Patient cohort and data

collection

The present study included 6 male patients and 5

female patients, with a mean age of 30.9±16.74 years. Clinical

features, outcomes, and related treatments were examined. The

disease-free survival period and overall survival rate were

calculated.

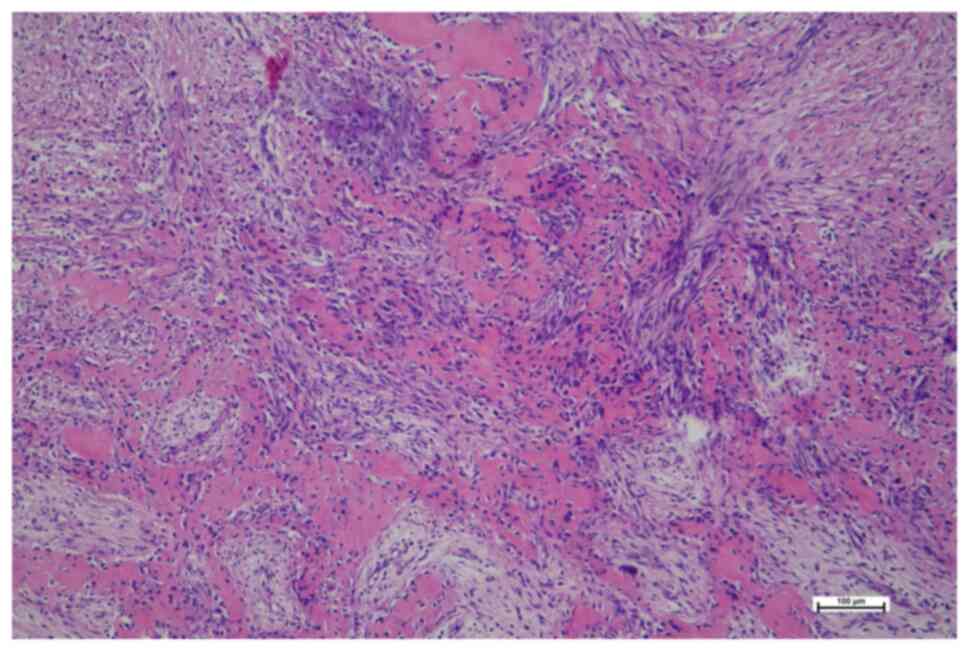

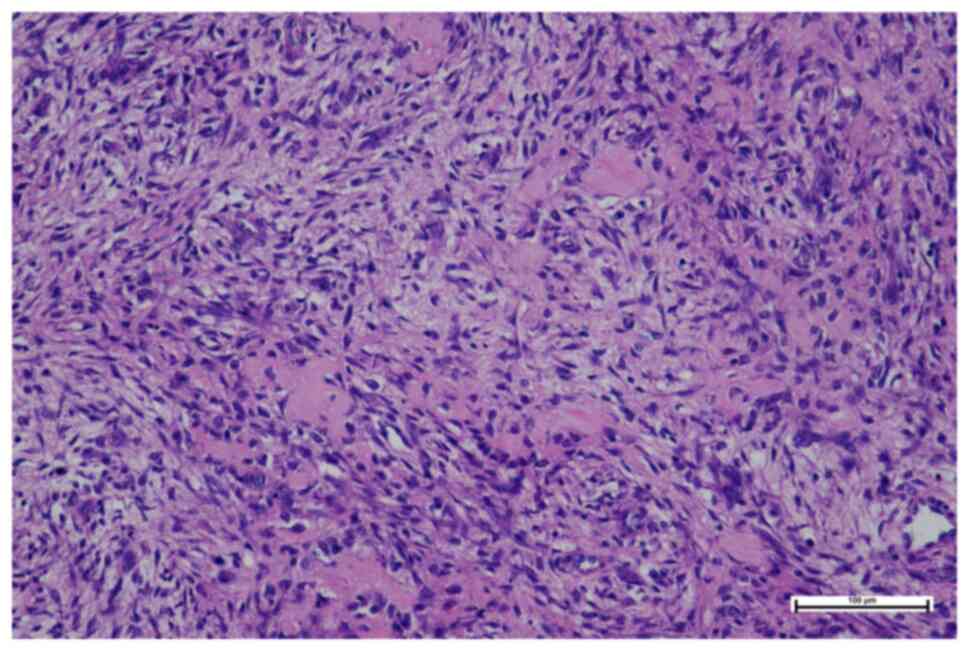

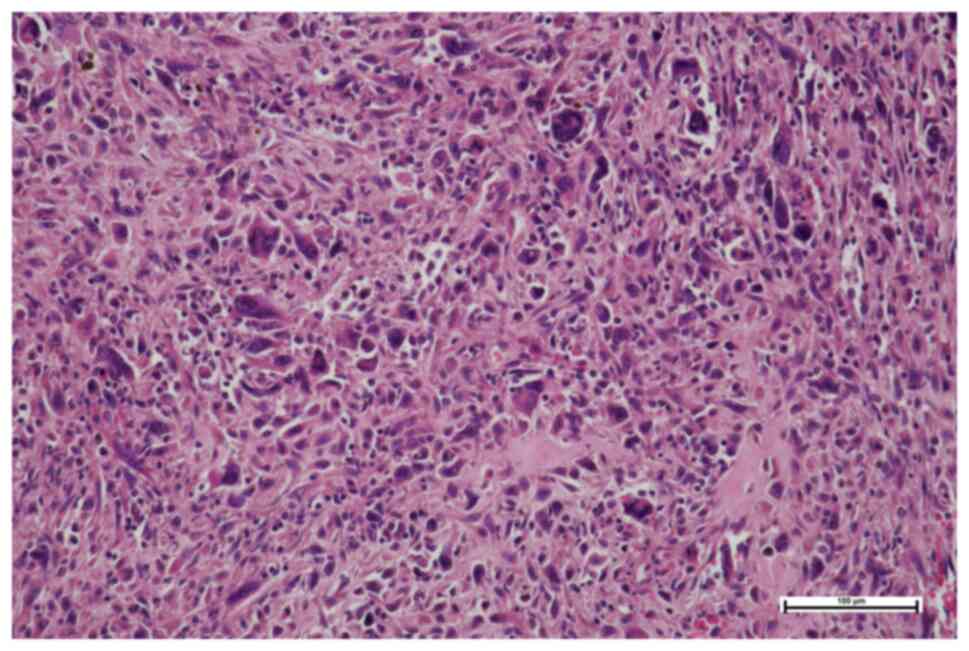

Histopathological review

Histological diagnoses were reviewed by an

experienced musculoskeletal oncology pathologist. The diagnoses

were confirmed using hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical

(IHC) staining.

The received tissue was macroscopically inspected,

and representative samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin for 24 h. Subsequently, the tissue samples were processed

using the Tissue Processor TPC15 (Bamed sro), involving alcohol,

isopropylene and xylene washes, followed by embedding in paraffin

at a constant temperature of 60°C. The entire process took 14.25 h,

with paraffin embedding taking the final 3.75 h. Calcified/ossified

components were decalcified by submerging them in a 10% EDTA

solution for 2–3 days before embedding.

The FFPE tissue was then sectioned into 4-µm thick

sections and routinely processed with hematoxylin-eosin staining

for 104 min at 60°C using Automatic stainer and coverslipper E7 or

Staining apparatus Medite TST44 in combination with Film

coverslipper Medite Twister (all Bamed sro). The stained tissue was

subsequently examined under a standard light microscope (Olympus

BX45; Olympus Corporation) at ×20, ×40, ×100 and ×200

magnification.

IHC analysis of SATB2, S100, Histone H3G34W and p63

expression was performed on tumor tissue sections using the

Automated IHC/ISH Slide Staining System BenchMarkXT (• Roche Tissue

Diagnostics). The ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Roche

Tissue Diagnostics) was used for staining according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The 4-µm thick tumor tissue sections

were applied to positively charged TOMO® slides

(Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd.). The following antibodies and

conditions were used for staining: i) SATB2 Rabbit Monoclonal

Antibody (clone EP281; cat. no. 384R-16; Cell Marque;

MilliporeSigma) at 1:100 dilution; cell conditioning Ultra CC1 for

36 min at 95°C; antibody incubation for 32 min at 37°C. ii) S100

Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (cat. no. Z0311; Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) at 1:1,000 dilution; cell conditioning Ultra

CC1 for 20 min at 95°C; antibody incubation for 28 min at 37°C.

iii) Histone H3G34W Antibody (clone RM263; cat. no. 31-1145-00-S;

RevMAb Biosciences USA, Inc.) at 1:200 dilution; cell conditioning

Ultra CC1 for 76 min at 95°C; antibody incubation for 32 min at

37°C. iv) p63 Antibody (clone 4A4; cat. no. 05867061001; Roche

Diagnostics GmbH), ready-to-use; cell conditioning Ultra CC1 for 72

min at 100°C; antibody incubation for 36 min at 37°C.

The ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Roche

Diagnostics GmbH) was used to detect expression for all the

aforementioned antibodies. Each run included a system of negative

and positive controls. Negative controls were prepared by

incubating samples without the primary antibody, while positive

control tissue samples were used to verify the staining. The

positive tissue controls were taken from residual tissue samples

obtained via biopsy/autopsy from different (already closed) cases.

All IHC results were evaluated using a uniform microscope and

camera setting (Olympus BX45 microscope and Olympus DR72 camera;

Olympus Corporation).

Follow-up and assessment

Postoperative follow-up assessments were conducted

at regular intervals every 3 months during the first 2 years, every

6 months for the next 3 years and annually thereafter. Each

follow-up included a clinical examination, plain radiographs of the

primary tumor site, chest CT scans, and, as needed based on the

clinical examination and radiograph findings, MRI of the primary

tumor site. Patients underwent follow-up appointments for a minimum

of 5 years, with a mean follow-up duration of 90.36 (±66.14)

months.

Ethical considerations and treatment

planning

The institutional review board approved the present

retrospective study, and written consent was obtained from all

patients or their legal guardians. Each case was presented to the

multidisciplinary Musculoskeletal Tumor Committee for treatment

planning and management.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software

(version 4.0.5; Posit Software, PBC) in the RStudio development

environment. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient

demographics, clinical characteristics, tumor size,

histopathological findings and survival rates. Categorical

variables, such as sex, tumor grade and histological type, were

reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables,

including patient age, follow-up duration and tumor size, were

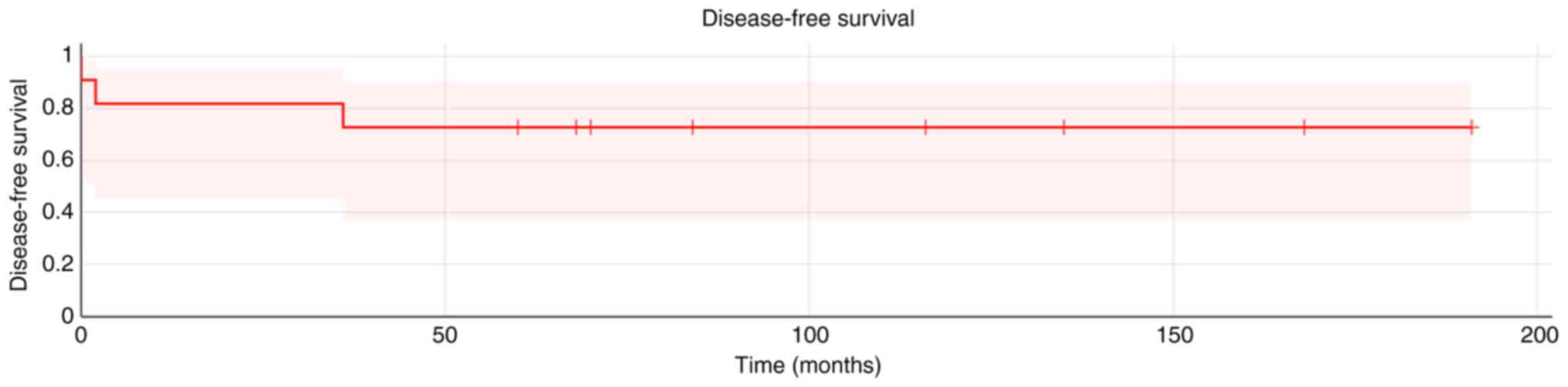

expressed as the mean ± SD. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to

estimate overall survival and disease-free survival rates. Mean

survival times and their corresponding 95% CIs were calculated.

Patients were censored at their last known follow-up date or time

of death.

Results

Clinical and pathological

outcomes

The mean tumor size detected during diagnosis was

4.29±1.81 cm. Osteoblastic osteosarcoma was the most common

histopathological type, accounting for 4 cases (33.4%). A majority

of the osteosarcomas were identified as high-grade (81.8%). Only 1

patient exhibited lung metastasis and lymph node infiltration upon

diagnosis (Table II). A total of 5

patients experienced misdiagnoses following the initial biopsy,

with two initially receiving treatment outside the Masaryk Memorial

Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center. The most frequently encountered

misdiagnosis was giant-cell tumor of bone (GCTB). Of the

misdiagnosed patients, 4 patients initially underwent an

intralesional procedure. Only 3 patients received CHT before their

procedure and 3 patients underwent limb amputation. A total of 4

patients underwent ray resection, and 4 underwent en bloc

resection, including an astragalectomy. A total of 2 patients

developed lung metastasis and succumbed to the disease (Table III). The disease-free survival

period was 82.83±60.05 months, while the overall survival rate was

72%, with a mean survival time of 90.36±56.73 months (Fig. 1). The overall survival rate for the

patients with high-grade osteosarcomas was 66%, with a mean

survival time of 85.11±55.89 months.

| Table II.Tumor characteristics. |

Table II.

Tumor characteristics.

| Tumor feature | Value |

|---|

| Number of tumors,

n | 11 |

| Location, n

(%) |

|

|

Hand | 5 (45.5) |

|

Foot | 6 (54.5) |

| Mean size (SD),

cm | 4.29 (±1.81) |

| Histology, n

(%) |

|

|

Osteoblastic | 4 (33.4) |

|

Giant-cell rich | 3 (27.3) |

|

Fibroblastic | 1 (9.1) |

|

Telangiectatic | 1 (9.1) |

|

Chondroblastic | 1 (9.1) |

|

Periosteal | 1 (9.1) |

| Grade, n (%) |

|

|

Low | 1 (9.1) |

|

Intermediate | 1 (9.1) |

|

High | 9 (81.8) |

| Stage, n (%) |

|

| I | 2 (18.2) |

| II | 7 (63.6) |

|

III | 2 (18.2) |

| Lymph node

involvement at diagnosis, n (%) | 1 (9.1) |

| Metastasis at

diagnosis | 1 (9.1) |

| Table III.Summary of 11 cases of hand or foot

osteosarcoma from the present study. |

Table III.

Summary of 11 cases of hand or foot

osteosarcoma from the present study.

| Patient | Age at diagnosis,

years | Sex | Misdiagnosis | Misdiagnosis

treatment | Histology | Tumor size, cm | Tumor site | Grade | Stage | Metastasis at

diagnosis | Neoadjuvant

CHT | Type of

surgery | Adjuvant CHT | Meta stasis | Event | Additional

therapy | Eventfree survival,

months | Overall survival,

months | Patient status at

time of writing |

|---|

| 1 | 46 | M | Malignant GCTB | N/A | Giantcell rich | 7.0 | IV. MTC | High | III | Lung and

skeletal | N/A | Amputation | N/A | N/A | Death | Palliative CHT | N/A | 12 | Died |

| 2 | 38 | M | N/A | N/A | Fibroblastic | 5.0 | Calca neus | High | II | N/A | N/A | Amputation | Yes | Lung | Death | N/A | 36 | 70 | Died |

| 3 | 11 | F | N/A | N/A | Periosteal | 3.0 | V.MTT | Intermediate | I | N/A | N/A | En bloc

resection and allograft | N/A | N/A | N/A | Suspected local

recurrence biopsy | 60 | 60 | Free of

disease |

| 4 | 26 | F | N/A | N/A | Osteoblastic | 2.5 | III. Digit of the

hand | High | II | N/A | N/A | Ray resection | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 68 | 68 | Free of

disease |

| 5 | 52 | M | Aneurysmal bone

cyst | Astragalectomy | Telangiectatic | 6.5 | Talus | High | II | N/A | Yes | Ampu tation | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 135 | 135 | Free of

disease |

| 6 | 19 | M | Enchondroma | Cure ttage and bone

grafting | Chondro

blastic | 2.5 | V. MTC | High | II | N/A | N/A | Ray resection | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 84 | 84 | Free of

disease |

| 7 | 50 | M | GCTB | Curettage and

cementoplasty | Giantcell rich | 4.0 | Talus | High | III | N/A | N/A | Astraga

lectomy | Yes | Lung | Death | Palliative CHT | 2 | 20 | Died |

| 8 | 17 | M | N/A | N/A | Osteo blastic | 6.0 | IV. MTT | High | II | N/A | Yes | En bloc

resection | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 191 | 191 | Free of

disease |

| 9 | 14 | F | GCTB | Curettage and bone

grafting | Osteo blastic | 2.0 | II. MTT | Low | I | N/A | N/A | Ray resection | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 168 | 168 | Free of

disease |

| 10 | 34 | F | N/A | N/A | Osteoblastic | 3.0 | IV. digit of the

hand | High | II | N/A | N/A | Ray resection | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 70 | 70 | Free of

disease |

| 11 | 19 | F | N/A | N/A | Giantcell rich | 3.0 | II. MTT | High | II | N/A | Yes | En bloc

resection | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 116 | 116 | Free of

disease |

Case presentation

Case 1

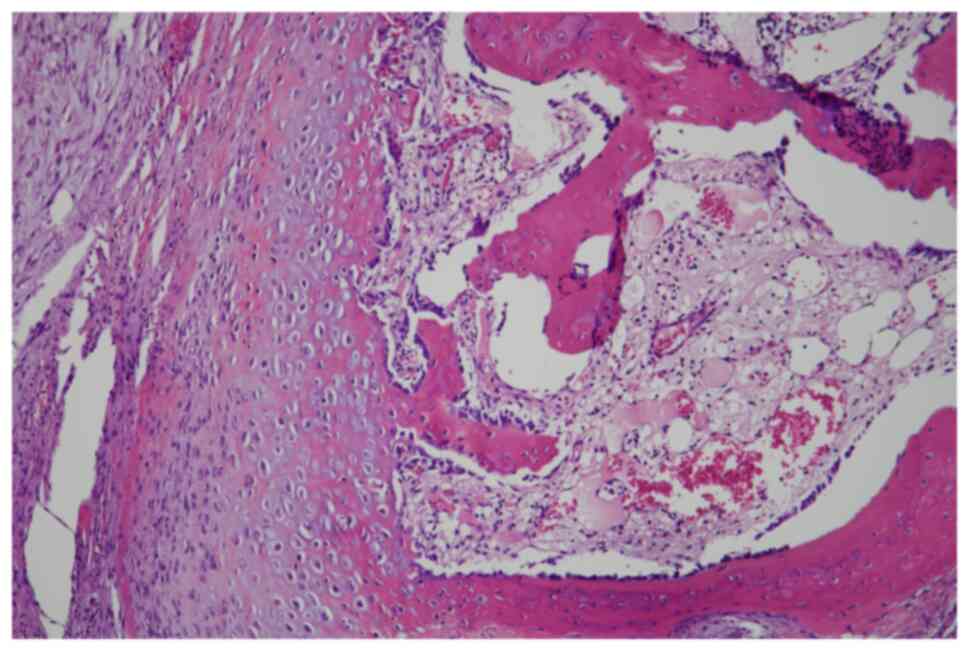

A 26-year-old female patient presented to a local

surgical department in the Moravian-Silesian region with a 3-month

history of persistent pain and swelling in the middle finger of

their left hand. An incision was made under local anesthesia, but

the lesion eventually ulcerated and in March 2018, the patient was

referred to the Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center

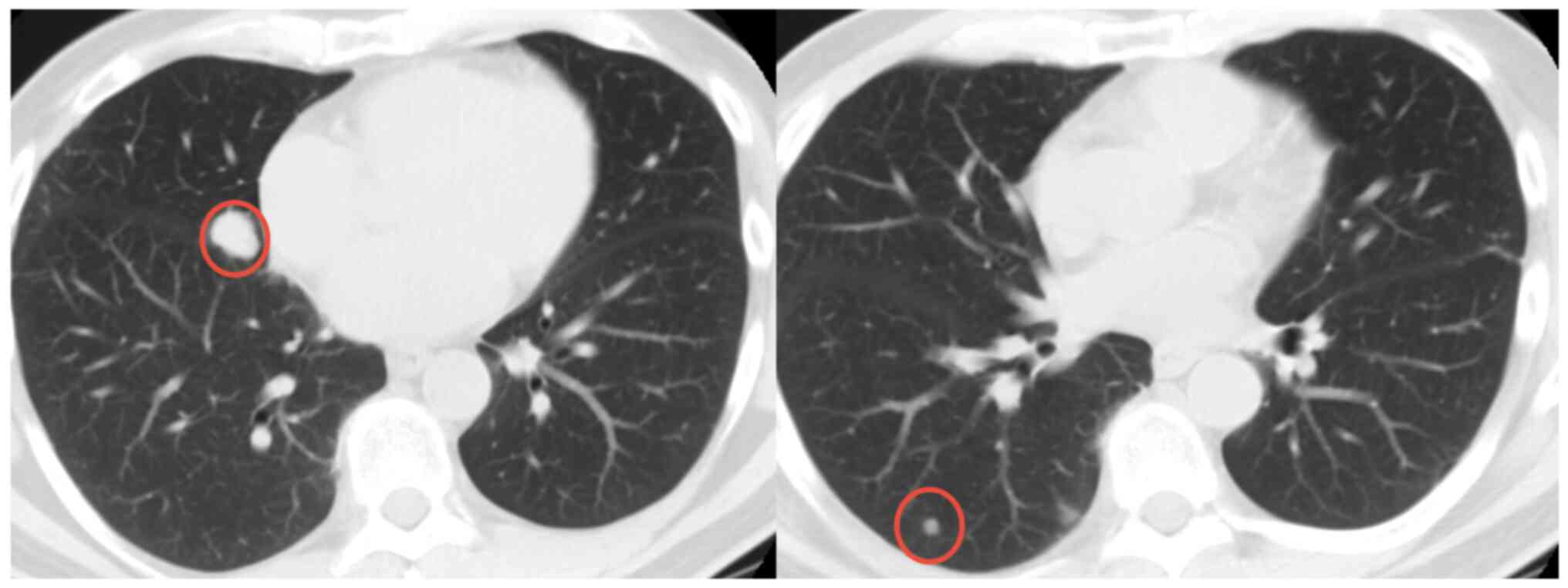

(Brno, Czechia) for further evaluation. CT scans demonstrated an

osteoblastic lesion in the middle phalanx (Fig. 2) and histopathology confirmed the

diagnosis of high-grade parosteal osteosarcoma (Fig. 3). The Musculoskeletal Tumor

Committee recommended resection of the third ray, which was

performed successfully (Fig. 4).

The final histopathology report indicated high-grade osteoblastic

osteosarcoma and a complete resection (Fig. 5). Following the surgery, the patient

underwent four cycles of the standard combination CHT regimen

(10), comprising high-dose

methotrexate (12 g/m2), doxorubicin (75

mg/m2) and cisplatin (120 mg/m2). However,

due to toxicity, the regimen was interrupted. Treatment was then

adjusted to two additional cycles of monotherapy, with doxorubicin

reduced (50 mg/m2) and methotrexate continued at 12

g/m2. At follow-up examinations, the patient remained

disease free. However, 5 years after the surgical procedure, the

patient died due to a sudden cardiac arrest, which was potentially

related to the cardiotoxic effects of the CHT.

Case 2

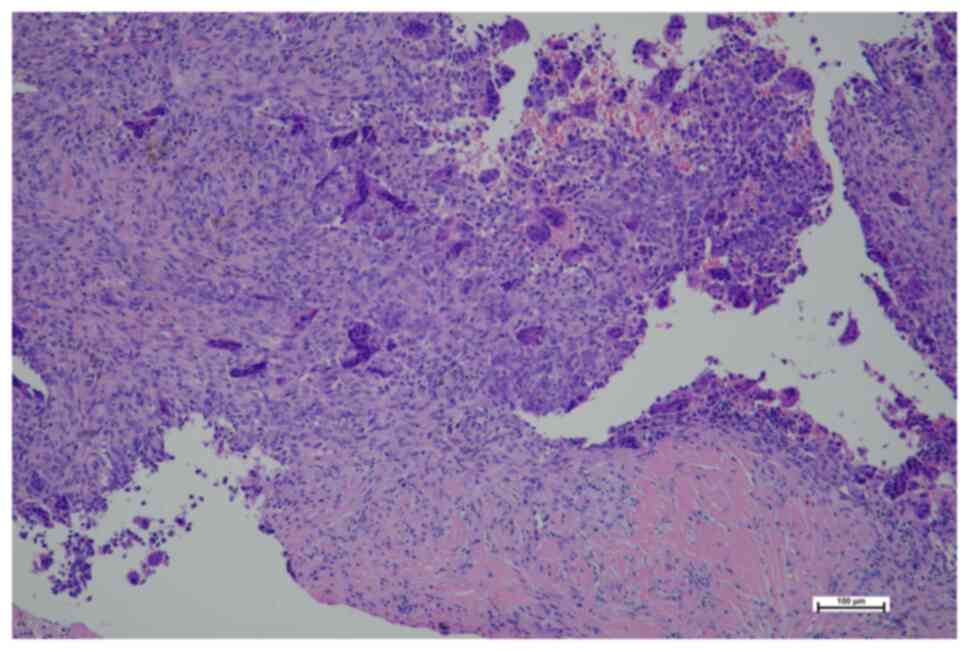

In September 2019, a 46-year-old male patient

presented to the Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center

(Brno, Czechia) with a 3-month history of pain and swelling in the

left hand and wrist. Computed radiography (CR) and MRI scans showed

an osteolytic lesion on the base of the fourth metacarpal bone and

carpal bones (Fig. 6). The

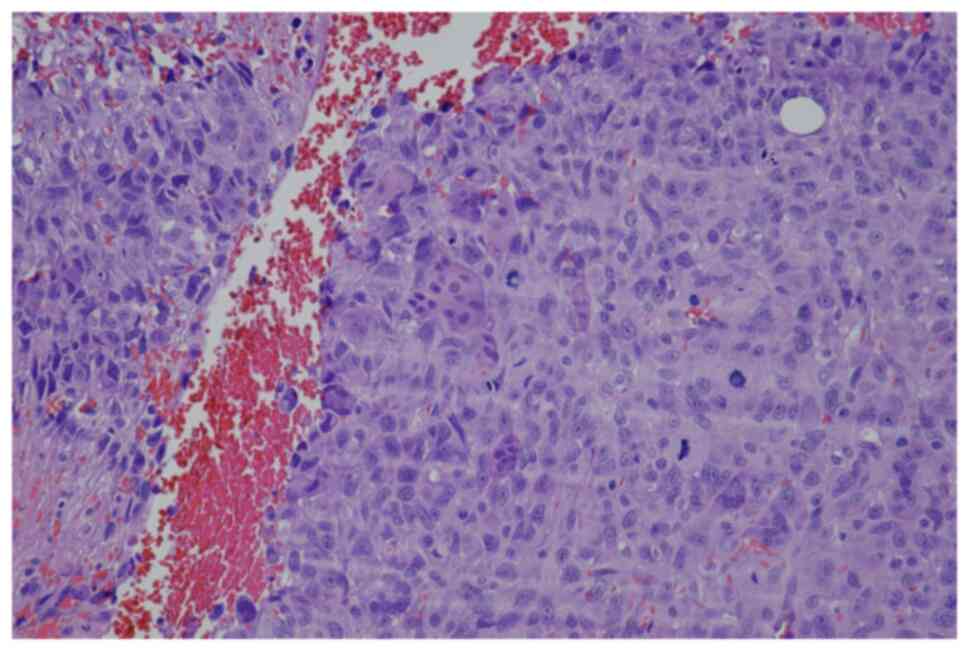

histopathology report indicated a primary malignant GCTB (Fig. 7). CT scans and radiographic imaging

showed infiltration of lymph nodes, as well as metastases to the

lungs (Fig. 8) and skeleton

(Fig. 9). The Musculoskeletal Tumor

Committee recommended a radical approach, suggesting amputation of

the affected area followed by palliative CHT. The final

histopathology report confirmed the presence of a 55-mm high-grade

giant cell-rich osteosarcoma (Fig.

10), which was successfully removed through complete resection.

The patient passed away 1-year after the surgery.

Case 3

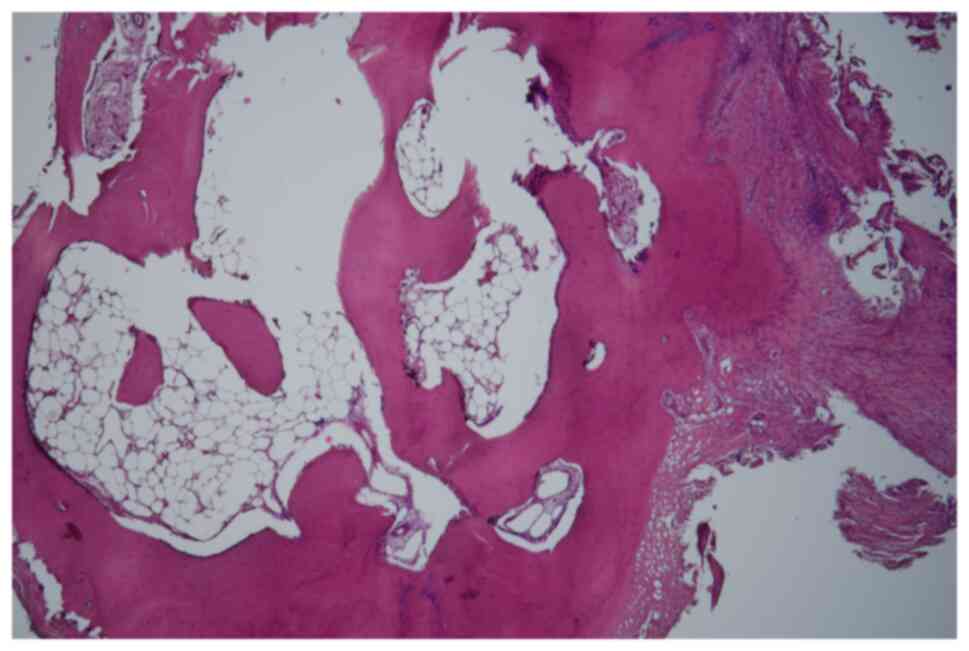

In January 2019, an 11-year-old female was referred

to the Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center with a

2-month history of pain in the right foot. MRI scans showed a 3 cm

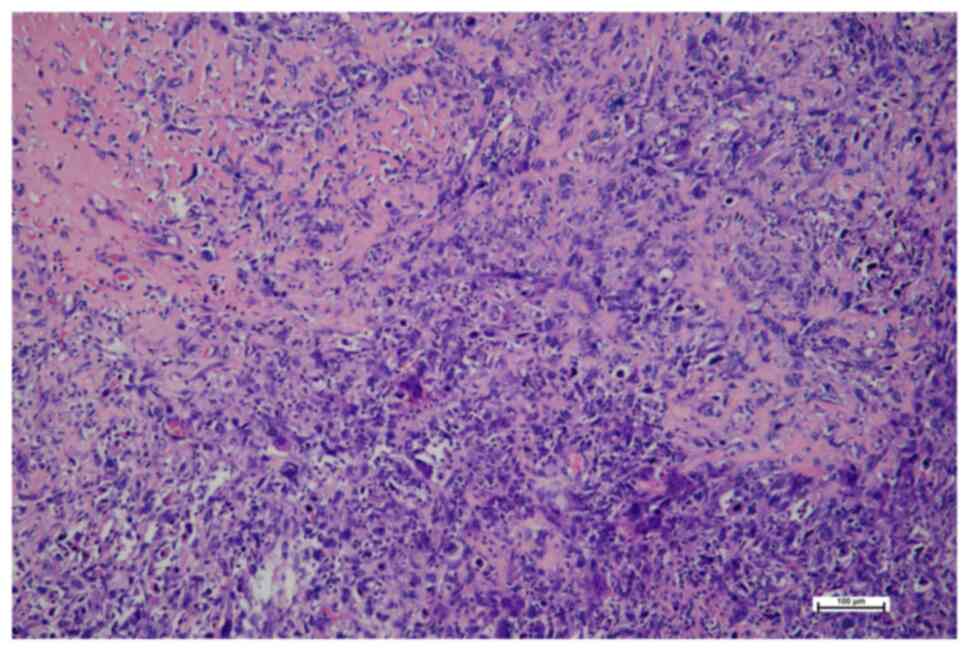

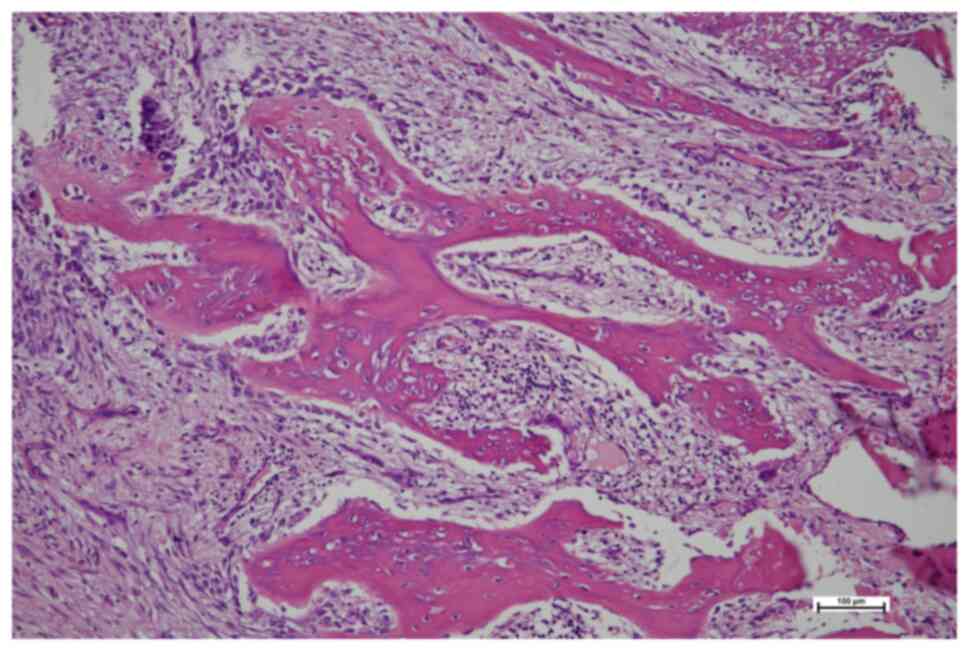

thickening of the bone in the V. metatarsal diaphysis (Fig. 11). The histopathology report showed

an intermediate-grade periosteal osteosarcoma (Fig. 12). The patient had no lymph node

involvement or metastases. The Musculoskeletal Tumor Committee

recommended en bloc resection with bone allograft

reconstruction using a plate. The final histopathology report

confirmed the initial findings from the biopsy (Fig. 13). After 2 years, a follow-up plain

radiographs showed ossification on the allograft surface (Fig. 14), leading to a biopsy to check for

any signs of local recurrence. The biopsy results showed no

evidence of malignancy (Fig. 15).

At the time of writing, the patient completed 5 years of follow-up

appointments with no signs of disease recurrence.

Case 4

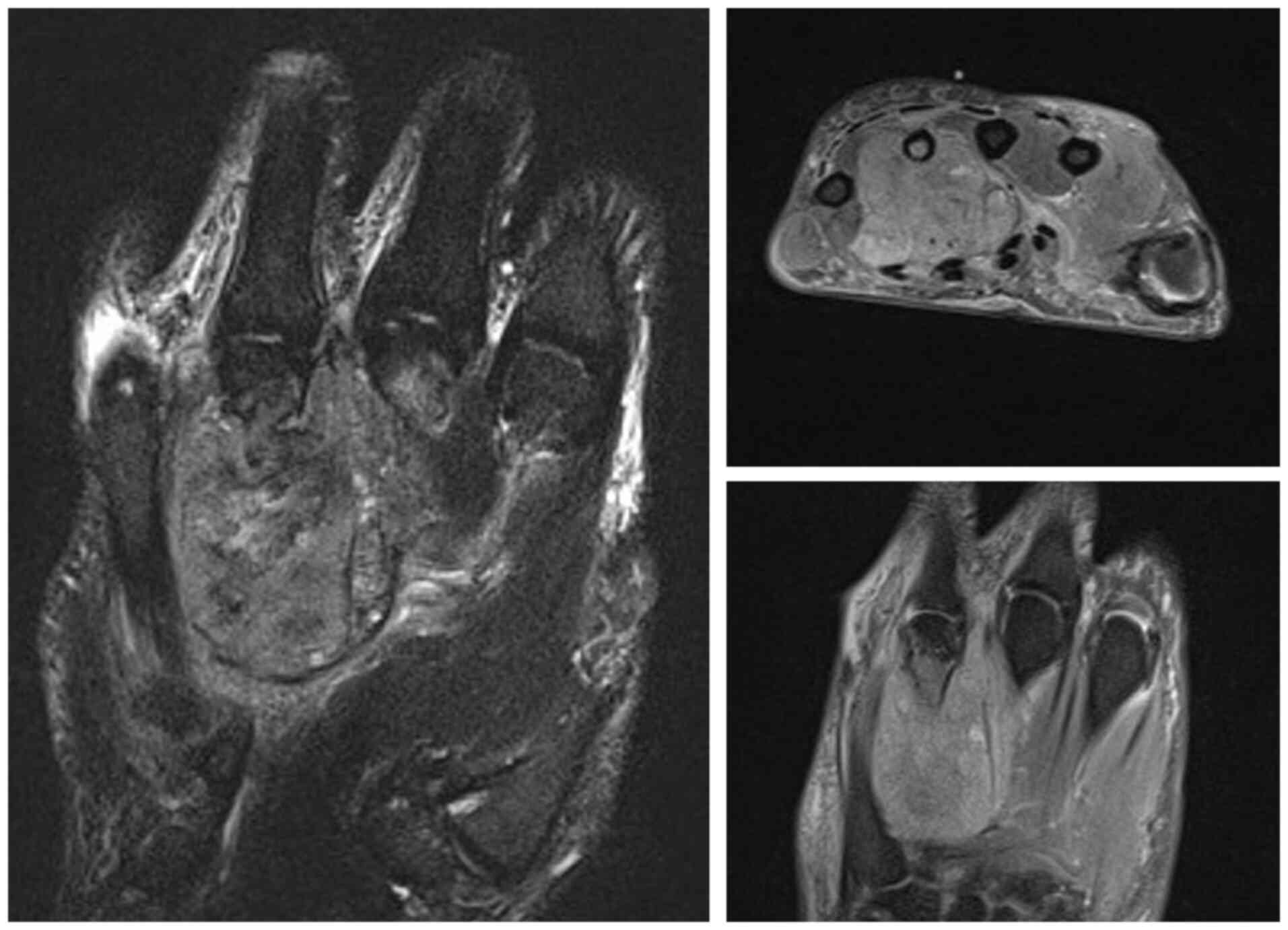

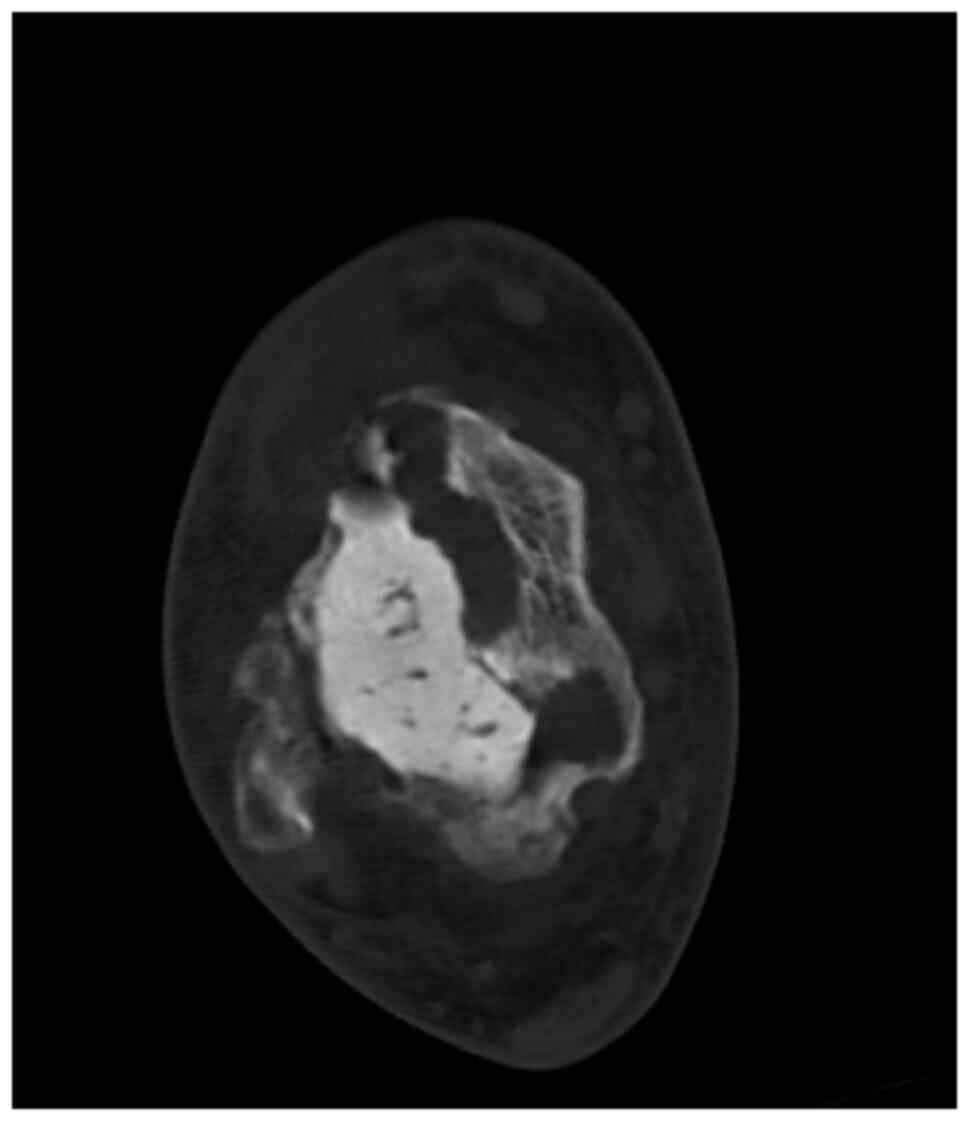

In June 2007, a 50-year-old male presented to the

Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute Sarcoma Center, with a 1-month

history of persistent pain in the right ankle. Further

investigations showed a cystic lesion of the talus on a CR scan,

which was later confirmed by a supplementary CT scan (Fig. 16). The histopathology report

diagnosed GCTB with a secondary aneurysmal cyst of the talus

(Fig. 17), leading to a

recommendation for intralesional resection with bone cement

augmentation. After receiving the recommended treatment, the

patient returned 5 months later with swelling and increased pain in

the ankle. A follow-up CT scan showed destruction of the bone

surrounding the bone cement, as well as osteolysis of the calcaneus

and the presence of an extraosseous mass proximally (Figs. 16 and 18). Due to the extent of osteolysis, the

patient required an astragalectomy. Subsequent histopathology

reports showed a diagnosis of giant-cell rich osteosarcoma,

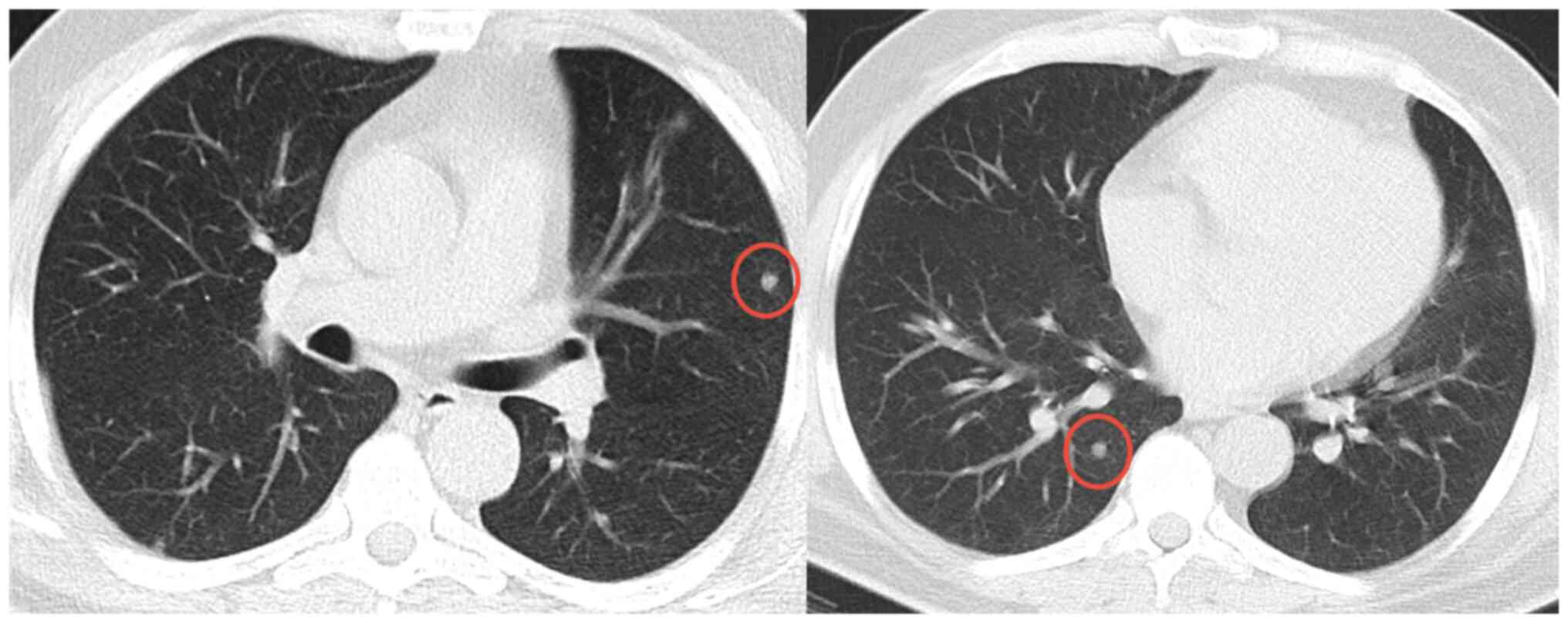

contradicting the initial findings (Fig. 19). Further staging scans indicated

the presence of lung metastases (Fig.

20). The Musculoskeletal Tumor Committee recommended

metastasectomy followed by adjuvant CHT. Despite the successful

removal of 12 lung metastases, the patient developed additional

lung metastases within two months. Despite palliative care efforts,

the patient died 6 months later.

Discussion

The occurrence of osteosarcoma in the hand and foot

regions is a rare clinical presentation, and patients with this

presentation of disease are diagnosed at an average age of nearly

10 years older than patients with osteosarcoma of the long bones.

This aligns with the general trend of osteosarcoma affecting an

older demographic in these specific body areas (11). Upon histological examination, low

grade (9.1%) and intermediate (9.1%) osteosarcomas are more common

in the distal extremities, in contrast to the typical distribution

observed in conventional osteosarcoma (11,12).

The occurrence of sarcomas in atypical anatomical locations has

been documented in previous reports (13,14).

There is a notable difference in the duration of

symptoms before diagnosis. Typically, osteosarcomas present

symptoms for <6 months in most cases (15). However, the findings of the present

study showed an average symptomatic duration of 9 months, which was

longer than the typical duration of symptoms for this disease.

Diagnostic delays for osteosarcomas in the distal skeleton have

been reported, with a number of patients being treated initially

for other conditions, such as GCTB (16,17).

In the present study, 1 patient presented with

metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, which represented a

higher rate than previously reported (16). All patients who died from the

disease had high-grade osteosarcomas. The overall survival rate for

high-grade variants was 66%, similar to those reported for

osteosarcomas of the long bones. Development of distant metastases

occurred regardless of the surgical approach used (18). The treatment for high-grade

osteosarcomas in the hands and feet should include neoadjuvant and

adjuvant CHT, along with aggressive surgery (12). A number of patients in the present

study required amputation, with the procedure being performed in

27.3% of cases.

The present study had several limitations. The first

was the study's retrospective design. The second was the small size

of the cohort, which included 11 cases, due to the rare nature of

the diagnosis of osteosarcoma of the hands and feet, which

restricted the generalizability of the findings. The present study

was conducted in a specific department with particular surgical

practices and patient populations. This may potentially limit the

applicability of the results to other settings or patient

demographics. However, osteosarcoma of the hand and foot is

particularly rare, and the majority of publications on peripheral

osteosarcoma consist of case reports or studies with ≤23 cases.

Multicenter studies also feature a limited number of patients

(16,19). The present study contributes to the

limited literature on peripheral osteosarcoma with practical

implications for treating cases involving the hand and foot. By

identifying common misdiagnoses and raising awareness about the

existence of osteosarcoma in these locations, even with a small

cohort, the present study could potentially enhance diagnostic

accuracy and timeliness, thereby preventing delays in

treatment.

Future perspectives on osteosarcoma diagnosis and

management could be advanced significantly by integrating

artificial intelligence (AI). AI-powered algorithms can be used to

analyze medical imaging modalities with greater accuracy and

efficiency compared with conventional methods that rely on human

expertise and interpretation (20).

Machine learning models, trained to recognize subtle patterns and

abnormalities in bone structures, may enable the earlier detection

of osteosarcoma, identifying indicators that may elude human

interpretation. Furthermore, AI-driven robotic systems can enhance

surgical precision, minimizing human error and improving outcomes

for patients undergoing bone resection and reconstruction (21).

In summary, a study was conducted on a case series

of 11 patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma of the hand and foot.

The present study described the treatment approach, clinical

characteristics and outcomes of these patients. A total of four

case studies of patients with osteosarcoma in these locations were

also presented. The present study demonstrated that misdiagnosis of

osteosarcoma of the hand and foot often led to patients being

administered with an incorrect treatment initially. The prognosis

of patients in the present study aligned with existing literature

and was favorable compared with that of osteosarcomas in other

anatomical regions. The present study adds valuable information to

the existing literature on osteosarcoma of the hand and foot by

providing essential data on clinical outcomes from a sarcoma

center, which may potentially help guide clinicians towards

effective treatment strategies for these patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MM, VA, DA, PM and DZ were responsible for the

writing and editing of the manuscript, and geneated the graph and

tables. MM, DA and PM were responsible for the methodology and data

collection. DA and MM were responsible for supervision of the

project. MM obtained resources and performed formal data analysis,

and VA was responsible for conceptualization of the study and

performing formal data analysis. LP and ISZ were responsible for

data collection and visualization and performing the methodology.

DZ contributed to the methodology, as well as the acquisition and

interpretation of data. TT was responsible for the

conceptualization, supervision methodology and formal data

analysis. MM and TT confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted according to the

guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the St.

Anne's University Hospital Ethics Committee (approval no.

EK-FNUSA-01/2024; Brno, Czech Republic). Written informed consent

was obtained from the patients or legal guardians.

Patient consent for publication

Patients or their legal guardians provided written

informed consent for publication of the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary,

taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CHT

|

chemotherapy

|

|

GCTB

|

giant cell tumor of bone

|

|

CR

|

computed radiography

|

|

AI

|

artificial intelligence

|

References

|

1

|

Picci P: Osteosarcoma (Osteogenic

sarcoma). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2:62007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Casadei R, Ferraro A, Ferruzzi A, Biagini

R and Ruggieri P: Bone tumors of the foot: Epidemiology and

diagnosis. Chir Organi Mov. 76:47–62. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Eyre R, Feltbower RG, James PW, Blakey K,

Mubwandarikwa E, Forman D, McKinney PA, Pearce MS and McNally RJQ:

The epidemiology of bone cancer in 0–39 year olds in northern

England, 1981–2002. BMC Cancer. 10:3572010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chou LB, Ho YY and Malawer MM: Tumors of

the foot and ankle: Experience with 153 cases. Foot Ankle Int.

30:836–841. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bowen CM, Landau MJ, Badash I, Gould DJ

and Patel KM: Primary tumors of the hand: Functional and

restorative management. J Surg Oncol. 118:873–882. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Brotzmann M, Hefti F, Baumhoer D and Krieg

AH: Do malignant bone tumors of the foot have a different

biological behavior than sarcomas at other skeletal sites? Sarcoma.

Mar 20–2013.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee JA, Lim J, Jin HY, Park M, Park HJ,

Park JW, Kim JH, Kang HG and Won Y-J: Osteosarcoma in adolescents

and young adults. Cells. 10:26842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Choong PFM, Qureshi AA, Sim FH and Unni

KK: Osteosarcoma of the foot: A review of 52 patients at the Mayo

Clinic. Acta Orthop Scand. 70:361–364. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Puri A: Limb salvage in musculoskeletal

oncology: Recent advances. Indian J Plast Surg. 47:175–184. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Whelan JS, Bielack SS, Marina N, Smeland

S, Jovic S, Hook JM, Krailo M, Anninga J, Butterfass–Bahloul T,

Böhling T, et al: EURAMOS-1, an international randomised study for

osteosarcoma: Results from pre-randomisation treatment. Ann Oncol.

26:407–414. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Whelan J, McTiernan A, Cooper N, Wong YK,

Francis M, Vernon S and Strauss SJ: Incidence and survival of

malignant bone sarcomas in England 1979–2007. Int J Cancer.

131:E508–E517. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, Kroon HMJA,

Vanel D, Alberghini M, Gelderblom H and Hogendoorn PCW:

Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: A distinct clinico-pathological

subgroup. Virchows Arch. 462:109–120. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vrînceanu D, Dumitru M, Ştefan AA,

Mogoantă CA and Sajin M: Giant pleomorphic sarcoma of the tongue

base-A cured clinical case report and literature review. Rom J

Morphol Embryol. 61:1323–1327. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Saifuddin MSAH, Ng CY and Abdullah MS:

Skull base primary ewing sarcoma: A radiological experience of a

rare disease in an atypical location. Am J Case Rep.

22:e9303842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Taran SJ, Taran R and Malipatil NB:

Pediatric Osteosarcoma: An Updated Review. Indian J Med Paediatr

Oncol. 38:33–43. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Schuster AJ, Kager L, Reichardt P,

Baumhoer D, Csóka M, Hecker-Nolting S, Lang S, Lorenzen S,

Mayer-Steinacker R, Kalle TV, et al: High-grade osteosarcoma of the

foot: Presentation, treatment, prognostic factors, and outcome of

23 cooperative osteosarcoma study group COSS patients. Sarcoma.

2018:1–11. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Biscaglia R, Gasbarrini A, Böhling T,

Bacchini P, Bertoni F and Picci P: Osteosarcoma of the bones of the

foot - An easily misdiagnosed malignant tumor. Mayo Clin Proc.

73:842–847. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kager L, Zoubek A, Pötschger U, Kastner U,

Flege S, Kempf-Bielack B, Branscheid D, Kotz R, Salzer-Kuntschik M,

Winkelmann W, et al: Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: Presentation

and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative

osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 21:2011–2018.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Okada K, Wold LE, Beabout JW and Shives

TC: Osteosarcoma of the hand: A clinicopathologic study of 12

cases. Cancer. 72:719–725. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Khalifa M and Albadawy M: AI in diagnostic

imaging: Revolutionising accuracy and efficiency. Comput Methods

Programs Biomed Update. 5:1001462024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Knudsen JE, Ghaffar U, Ma R and Hung AJ:

Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in robotic

surgery. J Robotic Surg. 18:1022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|