Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer

and sixth leading cause of mortality worldwide (1). Unresectable advanced or recurrent

esophageal cancer remains an intractable malignant disease, and

>10,000 people die annually from esophageal cancer in Japan

(2). In Japan, fluoropyrimidines

plus platinum-based chemotherapy was used as the first-line

therapy, followed by taxanes as the second-line therapy for

advanced esophageal cancer until the launch of immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs). Nivolumab, an anti-programmed cell death protein

1 (PD-1) antibody that reverts the ability of T cells to recognize

and kill tumor cells, showed a survival benefit over taxane for

esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC) patients who were refractory

to fluoropyrimidines- and platinum-based chemotherapy in the phase

III ATTRACTION-3 trial (3). Based

on these results, nivolumab has been approved in Japan since

February 2020 for ESCC patients who have progressed after

chemotherapy.

The ATTRACTION-3 trial showed a promising efficacy

with acceptable toxicity profiles for nivolumab; however, this

study excluded patients with a poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group performance status (ECOG-PS≥2) and consequently did not

include patients >70 years of age in the nivolumab group. A

small number of real-world data on nivolumab as second- or

further-line therapy has been reported (4); however, data on patients with

conditions that were excluded from the phase III ATTRACTION-3 trial

are still required. Thus, its efficacy and safety in these patients

are still unknown and worthy of further exploration in real-world

settings. Although ICIs, including nivolumab, demonstrate marked

and durable responses in some patients, they can occasionally cause

immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including fatalities.

Therefore, it is imperative to predict the efficacy of ICI therapy

before treatment initiation. Several reports suggest the usefulness

of biomarkers, such as PD-L1 expression with CD8+

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (5)

and inflammatory markers (CRP/albumin ratios (CAR)) (6), in predicting nivolumab efficacy in

ESCC; nonetheless, this information remains limited and lacking,

with no established biomarkers as of yet. Accumulating evidence has

shown that liver metastasis reduces the efficacy of ICI (7–11).

However, the potential value of liver metastasis as a predictor of

ICI efficacy for ESCC remains unclear. The identification of a

convenient and reliable biomarker for the ICI treatment of ESCC

remains a challenge.

Herein, we present the efficacy and safety of

nivolumab monotherapy as second or further-line therapy for ESCC

patients from a real-world data, with an analysis of the predictive

factors for treatment efficacy.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

We conducted a retrospective analysis of consecutive

patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent esophageal cancer

treated with nivolumab as a second- or later-line treatment at the

Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine between February 2020 and

December 2021. The data used in this study were extracted in

January 2022. All patients were pathologically confirmed to have

esophageal squamous or adenosquamous cell carcinoma and were

refractory or intolerant to at least one line of fluoropyrimidine-,

platinum-, or taxane-based chemotherapy. This study was approved by

the Medical Ethics Review Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University

of Medicine (approval no. ERB-E-42). All procedures were performed

in accordance with the ethical standards of the Medical Ethics

Review Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine

and the Declaration of Helsinki. An opt-out approach was employed

to obtain informed consent from patients, and personal information

was protected during data collection.

Treatment and evaluation

Intravenous nivolumab was administered at a dose of

240 mg every 2 weeks or 480 mg every 4 weeks. Treatment was

continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or

patient refusal. Information was collected from the electronic

medical records of the hospital. The data collected for this study

included sex, age, height, weight, ECOG PS, number and duration of

nivolumab administration, smoking and alcohol consumption,

histopathology, TNM at diagnosis, metastatic organ at diagnosis,

best response to primary therapy, overall survival (OS),

progression-free survival (PFS), blood test data (albumin, CRP,

neutrophils, lymphocytes), presence of surgery, presence of

radiation therapy, presence of treatment-related adverse events,

severity of treatment-related adverse events, and time to onset of

treatment-related adverse events. The overall response was

evaluated based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

version 1.1. The severity of adverse events was graded according to

CTCAE 4.0 criteria.

Statistical analysis

OS was defined as the time from the initiation of

nivolumab therapy until death by any cause or final follow-up. PFS

was defined as the time from the administration of the first dose

of nivolumab to disease progression or death. OS and PFS were

estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used

to compare groups, and Cox regression models were used to calculate

hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The

effects of liver metastases and possible factors, such as PS,

smoking status, and inflammatory markers (CAR,

neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and prognostic nutritional index

(PNI)), on PFS and OS were analyzed using COX regression models.

The cutoff values for NLR and PNI were determined based on previous

reports (12,13), and median value was employed for the

others.

PFS and OS were estimated with a 95% confidence

interval (CI) using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the

log-rank test. Cox regression models were used to calculate the

hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Significant variables in the

univariate analysis, P<0.05 for PFS and P≤0.01 for OS, were

included in the multivariate analysis. All statistical tests were

two-sided, and P<0.05 was set as the level of significance.

Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP Pro 17 software

(SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the 42 enrolled patients are

summarized in Table I. The median

age was 70 years old, with 22 patients (52%) aged 70 years or

older, a demographic not represented in the ATTRACTION-3 trial. The

proportion of males was 85%. The patients had ECOG-PS scores of 0

(n=21), 1 (n=18), or 2 (n=3). Histopathological findings included

squamous cell carcinoma in 41 patients (97%) and adenosquamous cell

carcinoma in one patient (3%). Nivolumab was used in 16 (38%)

second-line cases and 26 (61%) third-line or later cases. All the

patients received at least one regimen of fluoropyrimidine-,

platinum-, or taxane-based chemotherapy. Twenty-eight (66%) and 19

(45%) patients underwent surgery and radiation therapy,

respectively, prior to treatment. Twenty-five patients (40%) had

metastases in more than two organs, with the most prevalent

metastatic organs being the lymph nodes (88%), lungs (35%), and

liver (28%), followed by the bone (11%). Except for two patients

(5%) who were non-smokers, 40 patients (95%) had a history of

smoking (at least once).

| Table I.Characteristics of patients

(n=42). |

Table I.

Characteristics of patients

(n=42).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|

| Agea, years |

|

|

<65 | 12 (28) |

| ≥65 | 30 (71) |

| of which

≥70 | 22 (52) |

| Sex |

|

| Male | 36 (85) |

|

Female | 6 (14) |

| ECOG Performance

status |

|

| 0 | 21 (50) |

| 1 | 18 (42) |

| 2 | 3 (7) |

| Pathological

tissue |

|

| Squamous

cell carcinoma | 41 (97) |

|

Adenosquamous cell

carcinoma | 1 (3) |

| Treatment lines |

|

| 2nd | 16 (38) |

| 3rd or

lator | 26 (61) |

| Previous

therapies |

|

|

Surgery | 28 (66) |

|

Radiotherapy | 19 (45) |

| Systemic

anticancer therapy | 42 (100) |

| Number of organs with

metastases |

|

|

<2 | 17 (59) |

| ≥2 | 25 (40) |

| Site of

metastases |

|

| Lymph

node | 37 (88) |

|

Liver | 12 (28) |

| Lung | 15 (35) |

| Bone | 5 (11) |

| History of

smoking |

|

|

Never | 2 (5) |

| Not

never | 40 (95) |

Efficacy of nivolumab

The median observation period after nivolumab

therapy was 7.9 months (0.6–23.8), and the median number of doses

was nine (1–53). As shown in

Table II, two patients (4%) had a

complete response; nine (21%), a partial response; 22 (52%), stable

disease; and nine (21%), progressive disease. Response and disease

control rates were 26 and 78%, respectively. Four patients (9%)

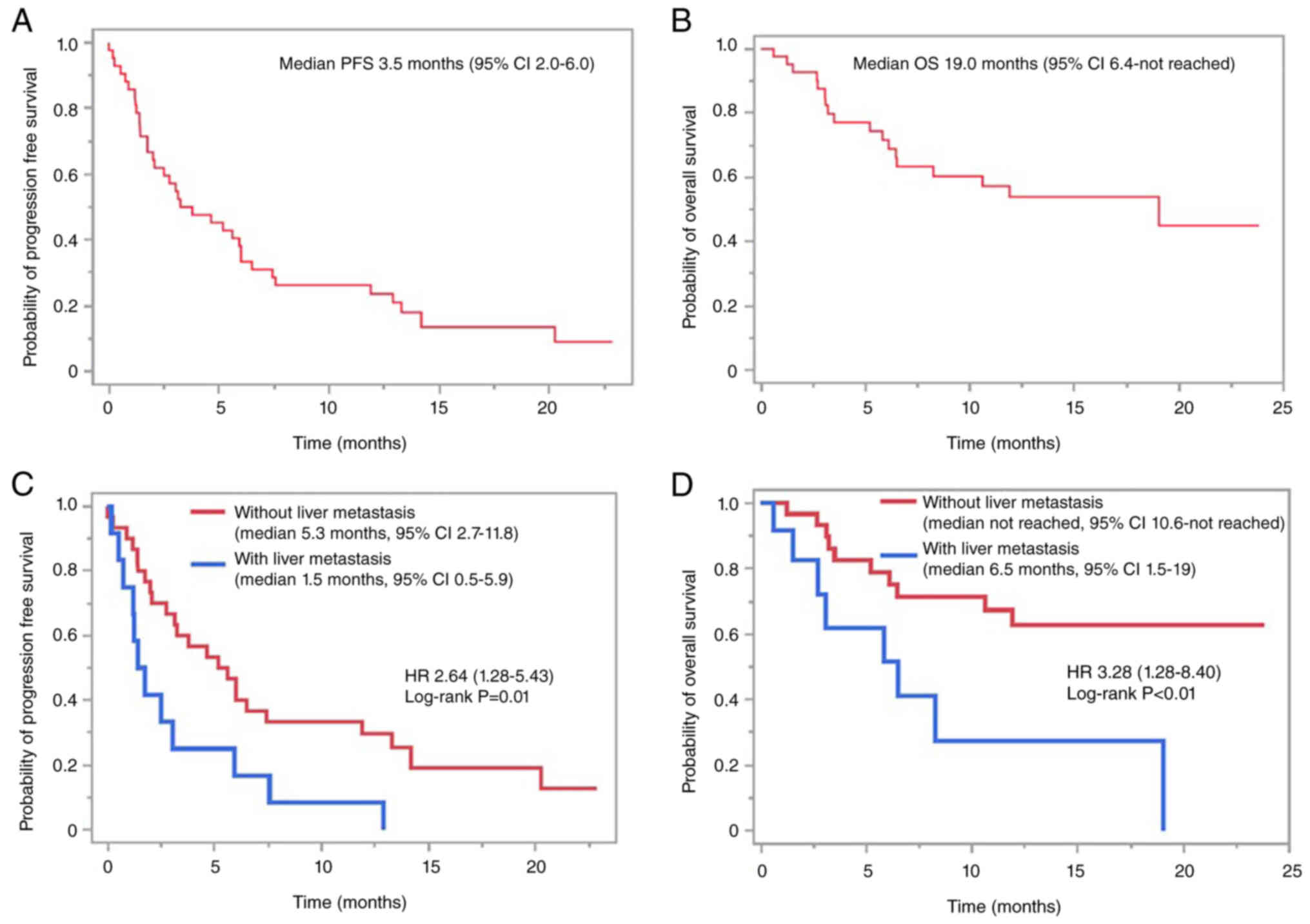

responded to nivolumab and continued treatment. The median PFS and

OS were 3.5 (95% CI 2.0–6.0, Fig.

1A) and 19 (95% CI 6.4-not reached, Fig. 1B) months, respectively. In a

comparison of PFS and OS based on liver metastatic status, PFS and

OS in patients without liver metastases were significantly better

than those with liver metastases (median PFS 5.3 vs. 1.5 months,

P=0.01, Fig. 1C; median OS not

reached vs. 6.5 months, P<0.01, Fig.

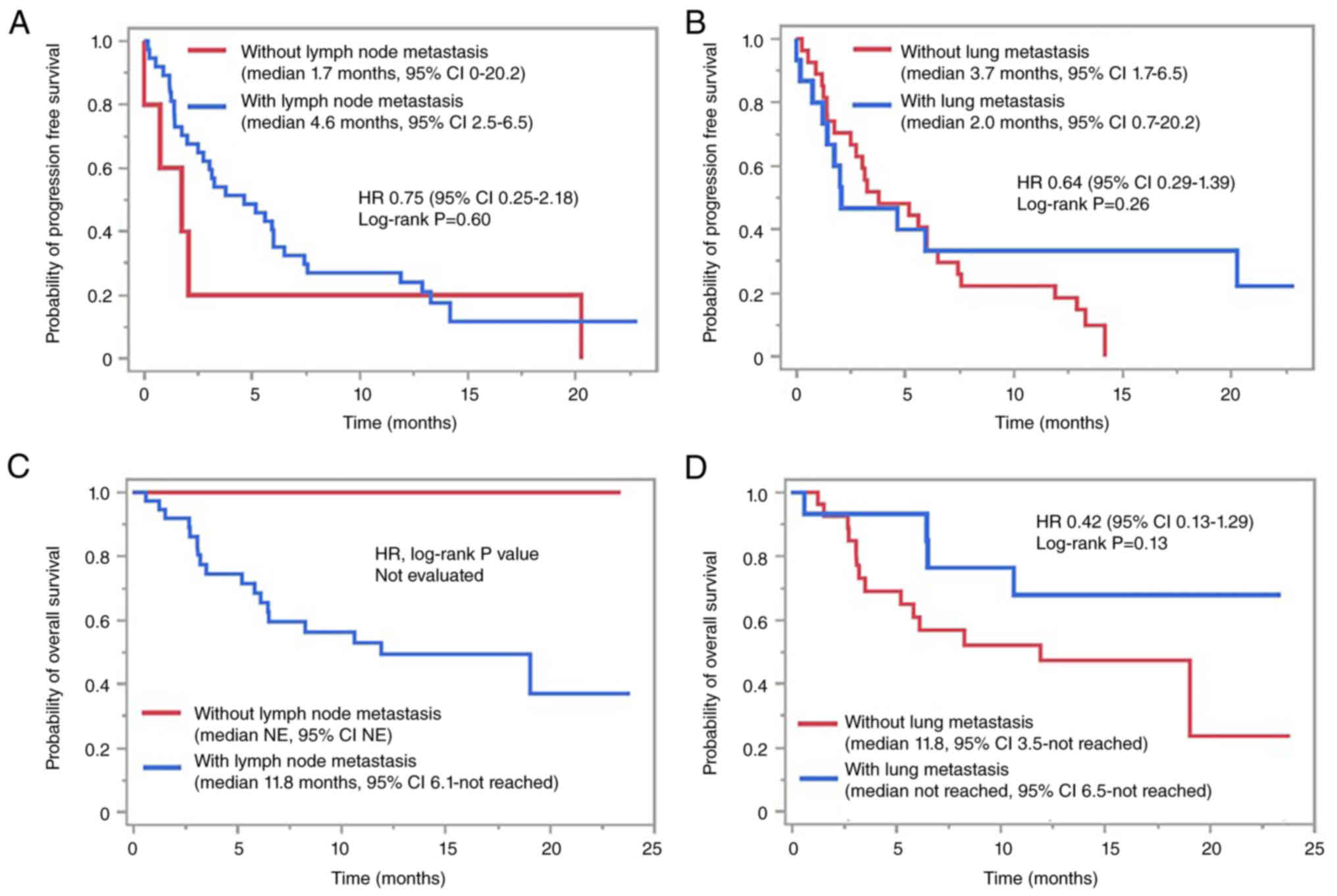

1D). In contrast, a comparison based on lymph node and lung

metastasis status showed no significant differences in PFS and OS

depending on the metastatic status, although there was a trend

toward longer OS in patients without lymph node metastasis

(Fig. 2).

| Table II.Treatment outcome (n=42). |

Table II.

Treatment outcome (n=42).

| Outcome | N |

|---|

| Doses of nivolumab

administered, n (range) | 9 (1–53) |

| Best overall

response, n (%) |

|

| Complete

response | 2 (4) |

| Partial

response | 9 (21) |

| Stable

disease | 22 (52) |

|

Progressive disease | 9 (21) |

| Not

evaluated | 0 |

| Disease control, n

(%) | 33 (78) |

| Response, n (%) | 11 (26) |

Predictive role of liver metastasis

and the other possible predictive factors

Factors, including liver metastatic status and

inflammatory markers, that may contribute to the PFS and OS of

nivolumab were analyzed. The following factors were included in the

analysis: age, ECOG-PS, smoking history, alcohol consumption, NLR,

CAR, hemoglobin level, PNI, and metastatic status. As shown in

Table III, the PFS was

significantly worse in patients with PS≥2 (HR 7.23, 95%CI

1.87–27.95, P=0.004), history of no smoking (HR 7.20, 95%CI

1.54–33.48, P=0.01), NLR≥4 (HR 3.33, 95%CI 1.65–6.73, P=0.0008),

bone metastasis (HR 3.63, 95%CI 1.29–10.2, P=0.01), and liver

metastasis (HR 2.64, 95%CI 1.28–5.43, P=0.008) in the univariate

analyses. In the multivariate analyses, liver metastasis (HR 2.37,

95%CI 1.07–5.24, P=0.03), history of no smoking (HR 5.81, 95%CI

1.07–31.35, P=0.04), and NLR≥4 (HR 2.53, 95%CI 1.21–5.76, P=0.02)

were shown to be possible worse predictive factors for PFS.

Table IV shows the univariate and

multivariate analyses of OS. In the univariate analyses, PS, NLR,

PNI, and liver metastasis were predictive factors. Because of the

small number of events occurring in the analysis of OS, fewer than

two explanatory variables in the multivariate analysis was

considered desirable; however, given the importance of liver

metastasis in previous reports (7–11), a

multivariate analysis was performed using three explanatory

variables including liver metastasis. Multivariate analysis

revealed that liver metastasis (HR 2.75, 95%CI 1.00–7.53, P=0.04)

and NLR≥4 (HR 3.15, 95%CI 1.17–8.49, P=0.02) were statistically

associated with worse OS.

| Table III.Univariate and multivariate analysis

for PFS. |

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

for PFS.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | Categories | Hazard ratio (95%

CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95%

CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | ≥65 vs. <65 | 1.22

(0.58–2.58) | 0.59 |

|

|

| ECOG PS | ≥2 vs. <2 | 7.23

(1.87–27.95) | <0.01 | 2.62

(0.42–16.03) | 0.29 |

| Smoking | Never vs. Current

or past | 7.20

(1.54–33.48) | 0.01 | 5.81

(1.07–31.35) | 0.04 |

| Alcohol

drinking | Yes vs. No | 0.55

(0.07–4.15) | 0.56 |

|

|

| NLR | ≥4 vs. <4 | 3.33

(1.65–6.73) | <0.01 | 2.53

(1.21–5.76) | 0.02 |

| PNIa | ≥40 vs. <40 | 0.58

(0.30–1.15) | 0.12 |

|

|

| CAR | ≥0.30 vs.

<0.30 | 1.19

(0.48–2.93) | 0.70 |

|

|

| Lung

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 0.64

(0.29–1.39) | 0.26 |

|

|

| Lymph node

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 0.75

(0.25–2.18) | 0.60 |

|

|

| Bone

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 3.63

(1.29–10.2) | 0.01 | 1.27

(0.28–5.65) | 0.75 |

| Liver

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 2.64

(1.28–5.43) | <0.01 | 2.37

(1.07–5.24) | 0.03 |

| Table IV.Univariate and multivariate analysis

for OS. |

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

for OS.

|

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variables | Categories | Hazard ratio (95%

CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95%

CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | ≥65 vs. <65 | 1.57

(0.51–4.79) | 0.42 |

|

|

| ECOG PS | ≥2 vs. <2 | 12.68

(2.07–77.42) | <0.01 | 5.39

(0.82–35.34) | 0.07 |

| Smoking | Never vs. Current

or past | 3.88

(0.87–17.15) | 0.07 |

|

|

| Alcohol

drinking | Yes vs. No | 0.13

(0.01–1.17) | 0.06 |

|

|

| NLR | ≥4 vs. <4 | 3.56

(1.38–9.13) | <0.01 | 3.15

(1.17–8.49) | 0.02 |

| PNIa | ≥40 vs. <40 | 0.36

(0.13–0.94) | 0.03 |

|

|

| CAR | ≥0.30 vs.

<0.30 | 0.82

(0.32–2.11) | 0.68 |

|

|

| Lung

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 0.42

(0.13–1.29) | 0.13 |

|

|

| Lymphnode

metastasis | Yes vs. No | Unreached | - |

|

|

| Bone

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 3.90

(0.77–19.77) | 0.09 |

|

|

| Liver

metastasis | Yes vs. No | 3.28

(1.28–8.40) | 0.01 | 2.75

(1.00–7.53) | 0.04 |

Frequency of immune-related adverse

events

IrAEs occurred in 12 of 42 patients (28%) of all

grades, with three (7%) patients experiencing grade 3 or higher

irAEs. Treatment discontinuation was required in three patients

(7%) who developed grade 3 pneumonitis (n=2) and thyroiditis (n=1).

No adverse events resulted in mortality. The most common irAEs were

thyroiditis and rash in four patients (9%), followed by diarrhea,

pneumonia, adrenal insufficiency, and pituitaryitis (Table V).

| Table V.Characteristics of immuno-related

adverse events (n=42). |

Table V.

Characteristics of immuno-related

adverse events (n=42).

|

Characteristics | All Grade, n

(%) | Grade 3/4, n

(%) |

|---|

| All events | 12 (28) | 3 (7) |

| Events leading to

discontinuation | 3 (7) | 3 (7) |

| Events leading to

death | 0 | 0 |

| Event details |

|

|

| Rash | 4 (9) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (4) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 |

| Thyroiditis | 4 (9) | 1 (2) |

| Pituitaryitis | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Interstitial

pneumonia | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Adrenal

insufficiency | 1 (2) | 0 |

Discussion

In the present study, the clinical efficacy and

safety of nivolumab as second- or third-line treatments for ESCC

were confirmed using real-world data. Notably, both treatment

efficacy and safety profiles were comparable to or better than

those of the phase 3 ATTRACTION-3 trial, despite the fact that our

study included a relatively large number of patients with poor PS

and aged >70 years, a demographic not included in the

ATTRACTION-3 trial. Furthermore, analysis of the predictors of PFS

and OS demonstrated that the presence of liver metastases is a

possible predictor of worse PFS and OS. Although there have been

several reports on the possibility that liver metastases may

attenuate the effects of ICIs (7–11),

this is the first report on ESCC to clearly demonstrate this

fact.

This study included patients over 70 years of age

(22 cases, 52%) and patients with PS2 (3 cases, 7%), both of which

were not included in the ATTRACTION-3 trial; however, the treatment

efficacy was rather favorable compared to that of the ATTRACTION-3

trial (overall response rate (ORR), 26% vs. 19%; disease control

rate (DCR) 78% vs. 37%; median PFS 3.5 vs. 1.7 months; median OS

19.0 vs. 10.9 months). Comparing the patient profile to that of the

ATTRACTION-3 trial, this study included fewer non-smokers (5% vs.

14%) and more patients over 65 years of age (71% vs. 47%). There

were no marked differences in the proportion of male patients,

number of metastatic organs, sites of metastasis, or prior

treatment. Smoking history has been reported to affect the efficacy

of ICI in non-small cell lung carcinoma (14–16),

and it is possible that the small number of non-smokers in this

study contributed to this favorable result. Since this was a

retrospective study with a small number of patients, coupled with

unknown PD-L1 status in most cases, discussing the reasons for more

favorable results than in the ATTRACTION-3 trial is constrained by

these limitations. Notably, the findings of this study, drawn from

real-world data that included a larger proportion of patients in

relatively poor condition, were comparable to or better than those

of the ATTRACTION-3 trial. Due to the small number of cases in this

study, we did not explore the difference in efficacy of nivolumab

by the treatment line (2nd vs. 3rd line or later), which should be

explored in future studies with larger sample sizes.

IrAEs were observed in 12 cases (28%), most of which

were mild. Grade 3 or higher irAEs were observed in 7% of patients,

and there were no treatment-related deaths. In patients aged

>70, five cases (22.7%) had irAEs of any grade, indicating no

increase in irAEs compared to younger patients. Only one case had a

grade 3 or higher adverse event (AE) (4%, interstitial pneumonia).

Although the retrospective nature of the study may have resulted in

an underestimation in assessing AEs, especially the mild ones, we

believe that this study provided evidence of the safety of this

treatment in real-world clinical practice.

We also examined the predictors of nivolumab

monotherapy. In the present study, no smoking history, liver

metastasis and high NLR (≥4) were independent poor predictive

factors for PFS and NLR and liver metastasis were the same for OS.

The confidence of the results for OS, however, needs to be

evaluated with caution due to the relatively small number of events

in this study. In addition to our results, numerous reports in

non-small cell lung have suggested that smokers treated with ICIs

have a better prognosis because of their stronger immunogenicity

and activated immune microenvironment (14–16).

NLR has the advantage of being easily derived from routine blood

tests and has proven to be useful as an indicator of systemic

immune status (17). Consistent

with our findings, several reports have shown that NLR has the

potential to be a predictive indicator for patients receiving ICIs

for various cancers (18–20). Patients with liver metastases had

significantly worse PFS and OS, whereas lung and lymph node

metastases showed no clear impact on the efficacy of nivolumab.

Furthermore, univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that

liver metastasis was an independent predictor of nivolumab

monotherapy. Consistent with our findings, Yu et al.

reported that liver metastases diminished immunotherapy efficacy in

patients and preclinical models (7). They demonstrated that the

effectiveness of ICIs was attenuated in melanoma and lung cancer

patients with liver metastases, contrasting with molecularly

targeted therapy or cytotoxic chemotherapy. They also demonstrated

that, in a preclinical model, liver metastases induced systemic

tumor-specific CD8+ T cell loss through apoptosis following their

interaction with activated monocyte-derived macrophages, thereby

reducing ICI efficacy. There have been several other reports on the

mechanisms of liver metastasis-induced reduction in the efficacy of

ICI. Liver metastases cause the loss of tumor-specific effector T

cells and loss of function in activated Treg cells and/or liver

macrophages (10,11). Recently, it was reported that in the

1st line treatment for ESCC, liver metastases patients

tended to develop progression disease early after the initiation of

nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy (21). In gastric cancer, hyper progression

after ICI therapy is reported to be significantly more common in

cases with liver metastasis (8).

Therefore, the risk of early disease progression should be also

considered when using nivolumab in esophageal cancer patients with

liver metastases. Taken together, liver metastasis is a potential

biomarker for nivolumab treatment in ESCC. These results should be

confirmed in future prospective studies owing to the inherent

potential biases of our analyses.

This study had several limitations. The main

limitation was that this was a retrospective study with a

relatively small sample size and was conducted at a single center.

Approximately six (14%) patients were currently undergoing

treatment, and 17 (40%) patients were being followed up in the

event of death; therefore, the OS data may be immature.

Furthermore, most cases in this study could not be evaluated for

PD-L1 expression because nivolumab was approved for use regardless

of PD-L1 expression.

In conclusion, this study provided real-world data

on patients with diverse profiles, such as elderly patients and

those with poor PS, unlike the phase 3 ATTRACTION-3 trial, in which

nivolumab provided favorable efficacy with no increase in serious

irAEs. In this study, liver metastases and NLR were identified as

potential predictive biomarkers of nivolumab efficacy in ESCC.

Further studies with larger numbers of patients are warranted to

validate these findings.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RM and TI confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. RM, TI, TD, JI, DS, NI, KI, HirK, OD, NY, AS, KU, TT, HF,

HidK and YI contributed to the study conception and design. RM, TI

and TD designed this study. RM contributed to data collection. RM

and TI analyzed the data. TD, JI, DS, NI, KI, HirK, OD, NY, AS, KU,

TT, HF, HidK and YI supervised the study. RM and TI wrote the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of

Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval no. ERB-E-42)

and conducted following the declaration of Helsinki principles and

its amendment. All authors read the final manuscript and approved

it for publication. An opt-out approach was employed to obtain

informed consent from patients, and personal information was

protected during data collection.

Patient consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I,

Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A and Bray F: Estimating the

global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and

methods. Int J Cancer. 144:1941–1953. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, Kikuchi S, Qiao Y,

Ueda J, Wei W, Inoue M and Tanaka H: Epidemiology of esophageal

cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol. 23:233–242. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, Okada M, Lin

CY, Chin K, Kadowaki S, Ahn MJ, Hamamoto Y, Doki Y, et al:

Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal

squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous

chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): A multicentre, randomised, open-label,

phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20:1506–1517. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kim JH, Ahn B, Hong SM, Jung HY, Kim DH,

Choi KD, Ahn JY, Lee JH, Na HK, Kim JH, et al: Real-world efficacy

data and predictive clinical parameters for treatment outcomes in

advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Res Treat. 54:505–516. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Farhood B, Najafi M and Mortezaee K: CD8+

cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J Cell

Physiol. 234:8509–8521. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ikoma T, Shimokawa M, Matsumoto T, Boku S,

Yasuda T, Shibata N, Kurioka Y, Takatani M, Nobuhisa T, Namikawa T,

et al: Inflammatory prognostic factors in advanced or recurrent

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 72:427–435. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yu J, Green MD, Li S, Sun Y, Journey SN,

Choi JE, Rizvi SM, Qin A, Waninger JJ and Lang X: Liver metastasis

restrains immunotherapy efficacy via macrophage-mediated T cell

elimination. Nat Med. 27:152–164. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sasaki A, Nakamura Y, Mishima S, Kawazoe

A, Kuboki Y, Bando H, Kojima T, Doi T, Ohtsu A, Yoshino T, et al:

Predictive factors for hyperprogressive disease during nivolumab as

anti-PD1 treatment in patients with advanced gastric cancer.

Gastric Cancer. 22:793–802. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR,

Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Sosman JA,

Atkins MB and Leming PD: Five-year survival and correlates among

patients with advanced melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, or non-small

cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. JAMA Oncol. 5:1411–1420.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lee JC, Mehdizadeh S, Smith J, Young A,

Mufazalov IA, Mowery CT, Daud A and Bluestone JA: Regulatory T cell

control of systemic immunity and immunotherapy response in liver

metastasis. Sci Immunol. 5:eaba07592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K,

Tanegashima T, Lin YT, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Irie T, Okumura G, Kono

H, et al: Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T

cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell.

40:201–218.e9. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B,

Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, Leibowitz-Amit R, Sonpavde G,

Knox JJ, Tran B, et al: Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J

Natl Cancer Inst. 106:dju1242014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang L, Ma W, Qiu Z, Kuang T, Wang K, Hu

B and Wang W: Prognostic nutritional index as a prognostic

biomarker for gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 14:12199292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nakahama K, Izumi M, Yoshimoto N, Fukui M,

Sugimoto A, Nagamine H, Ogawa K, Sawa K, Tani Y, Kaneda H, et al:

Influence of smoking history on the effectiveness of

immune-checkpoint inhibitor therapy for non-small cell lung cancer:

Analysis of real-world data. Anticancer Res. 43:2185–2197. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sun Y, Yang Q, Shen J, Wei T, Shen W,

Zhang N, Luo P and Zhang J: The effect of smoking on the immune

microenvironment and immunogenicity and its relationship with the

prognosis of immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung

cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7458592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang X, Ricciuti B, Alessi JV, Nguyen T,

Awad MM, Lin X, Johnson BE and Christiani DC: Smoking history as a

potential predictor of immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in

metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst.

113:1761–1769. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Giustini N and Bazhenova L: Recognizing

prognostic and predictive biomarkers in the treatment of non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

Lung Cancer (Auckl). 12:21–34. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sacdalan DB, Lucero JA and Sacdalan DL:

Prognostic utility of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in

patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: A review and

meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 11:955–965. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xie X, Liu J, Yang H, Chen H, Zhou S, Lin

H, Liao Z, Ding Y, Ling L and Wang X: Prognostic value of baseline

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in outcome of immune checkpoint

inhibitors. Cancer Invest. 37:265–274. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Muhammed A, Fulgenzi CAM, Dharmapuri S,

Pinter M, Balcar L, Scheiner B, Marron TU, Jun T, Saeed A,

Hildebrand H, et al: The systemic inflammatory response identifies

patients with adverse clinical outcome from immunotherapy in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 14:1862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chau I, Ajani JA, Doki Y, Xu J, Wyrwicz L,

Motoyama S, Ogata T, Kawakami H, Hsu C, Adenis A, et al: Nivolumab

(NIVO) plus chemotherapy (chemo) or ipilimumab (IPI) versus chemo

as first-line (1L) treatment for advanced esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma (ESCC): Expanded efficacy and safety analyses from

CheckMate 648. J Clin Oncol. 40 (Suppl 16):S4035. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|