Introduction

Malignant lymphomas constitute a biologically

heterogeneous group of diseases resulting from the clonal expansion

of lymphocytes (1) and they are

categorized based on their presumed cell of origin (either B-cell

or T-cell), their morphology (Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin), and their

level of cell differentiation (2).

Approximately one fourth of all lymphomas originate from extranodal

tissues, with the gastrointestinal tract and skin being the most

common sites (3). Lymphomas that

arise from the gynecological tract are less common, representing

around 1% of extranodal lymphomas. Of these, less than 1% emerge

from the uterine cervix (4).

The symptoms of primary lymphoma of the uterine

cervix (PLUC) often mimic those of cervical epithelial tumors. A

notable number of patients present with atypical symptoms such as

bleeding and pain, and pelvic exam usually reveals cervical oedema.

Since PLUC tend to develop in the cervical stroma rather than the

mucosa, it has been suggested that cytology cannot serve as a

reliable diagnostic tool, which creates a diagnostic challenge for

clinicians (5). This characteristic

limits the utility of traditional cytological screening methods,

such as the Pap smear, which are designed to detect epithelial

abnormalities. As a result, cytology often produces false negatives

in PLUC cases and therefore has limited efficacy as an initial

diagnostic tool. Given this, reliance on histopathological

examination through biopsy and the use of imaging modalities, such

as MRI and CT scans, is crucial for accurate diagnosis (6). PLUC bear histopathological resemblance

to lymphomas that occur in other anatomical sites. However, the

characterization of the malignancy as primary can be difficult

because the disease often involves contiguous sites including the

uterus and the vagina (6).

The optimal therapeutic management of patients with

female genital tract lymphomas and PLUC comprise another matter of

debate due to the rarity of the disease, the presence of different

histopathological subtypes that respond differently to treatment

and the lack of prospectively designed studies on the disease.

According to a body of evidence which is mainly based on case

reports and series, treatment options may encompass surgery,

chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or various combinations of the above

(7). Multidisciplinary co-operation

between gynecologists, pathologists, hematologists and medical

oncologists has been strongly recommended for the management of

patients diagnosed with the disease.

Given the limited clinical data on PLUC, we sought

to thoroughly review the existing literature and summarize the

reported cases. Our focus was on the clinicopathological features,

diagnosis, and treatment approaches associated with this

condition.

Materials and methods

Registration

This review was reported based on the ‘Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA)

guidelines (8). The protocol was

registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023424206).

Literature search

Title screening was managed using Covidence. Two

reviewers (SB, AS) independently searched PubMed, Web of Science

and Scopus library databases from inception until August 2023. The

search included the following terms: ‘Lymphoma’ AND (‘cerv*’ OR

‘vagina*’ OR ‘uter* OR ‘gynecological tract’). No restrictions

regarding study design, geographic region or language were applied.

To identify any overlooked studies, we also conducted a manual

search of the references cited in the selected articles and

relevant published reviews. Additionally, Google Scholar, tailored

Google searches, and consultations with experts were employed to

locate further articles from grey literature sources. Any

discrepancies during the search process were addressed by involving

a third investigator (KSK).

Eligibility criteria

All study designs were considered eligible for

inclusion only if they provided data for cases diagnosed with PLUC.

The definition of PLUC was based on the definitions provided by the

authors of the included studies (lymphoma presenting only in the

uterine cervix with no visible lymphadenopathy on imaging or larger

involvement of the uterine cervix in case of lymphoma presence on

contiguous sites). Review articles, conference abstracts, and

non-peer reviewed sources were not eligible for inclusion. We also

excluded published dissertations, studies in vitro and

animal models.

Data extraction and handling

Non-English articles were manually translated when

possible (9–15). In all studies, patient data was

retrieved and handled by two authors (SB, AS) who conducted the

data extraction independently. We collected the following

information when available: Sex, age, menopausal status,

comorbidities, family history of cancer, presenting symptoms and

duration of symptoms, laboratory tests, primary diagnosis,

histopathological markers, imaging findings, staging, therapeutic

management, follow up time and clinical outcome (overall survival

and disease-free survival). Any disagreements were discussed and

resolved by a third investigator (KSK).

Quality assessment

The risk of bias (RoB) was evaluated independently

by two authors (SB, AS). To assess the overall quality of the case

reports and case series, we utilized the critical appraisal

checklist from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (16), which has been reliably employed in

similar studies. The evaluation focused on eight key elements:

patient demographics, medical history, current health status,

physical examination and diagnosis, concurrent therapies,

post-intervention health outcomes, and the interaction between drug

administration and patient response. Each study was rated as ‘Yes’,

‘No’, or ‘Unclear/Not Applicable’ based on the availability and

clarity of the information for each element.

Data synthesis

This review employs descriptive statistics to

present the demographics and clinical features, including symptoms,

imaging methods, treatment approaches, staging, follow-up duration,

and outcomes. Continuous variables are summarized using means,

while binary variables are presented as rates or percentages. The

duration of symptoms is reported as a range to account for the

inconsistent and approximate reporting of this data across

different studies.

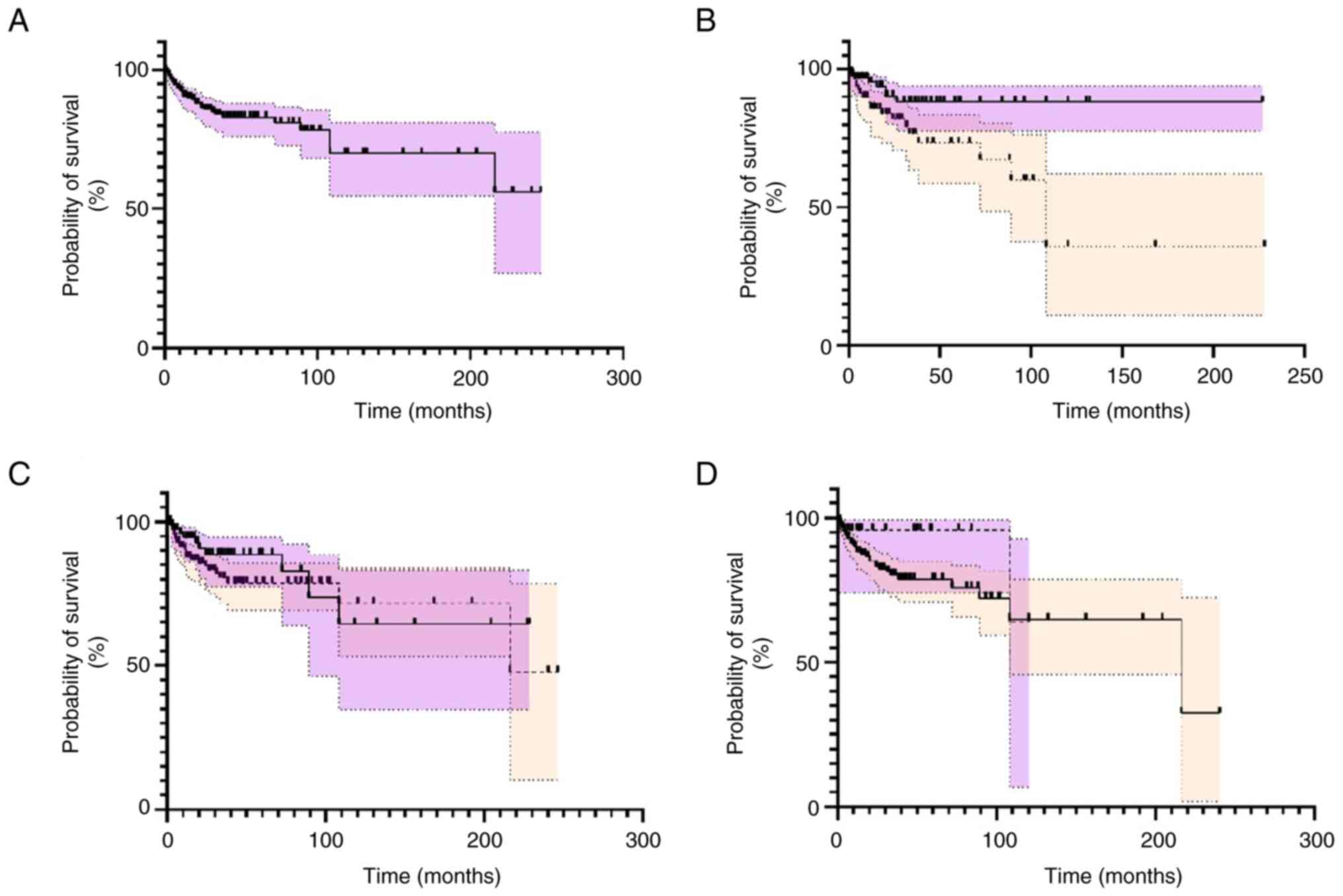

Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to estimate

overall survival irrespective of treatment used using GraphPad

PRISM 9.0. Data was pooled when duration of follow up (in months)

and outcome (alive or deceased) were provided. Duration of follow

up was converted to months and the definition for overall survival

was based on the definitions provided by the authors of the

included studies. The patients were divided into different

subgroups based on menopausal status, therapeutic management,

hysterectomy type, use of adjuvant treatments and staging at

diagnosis (supplementary material). Further sensitivity analyses

were performed, to ensure homogeneity of data, excluding studies

with high risk of bias, excluding pre-menopausal patients and

excluding patients with high stage disease based on Ann Arbor

staging system. Data with a P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant. Missing and unidentifiable data were excluded from the

statistical analysis. Both the log-rank test and the

Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon method were used to compare the survival

trend between the different subgroups.

Results

Study characteristics

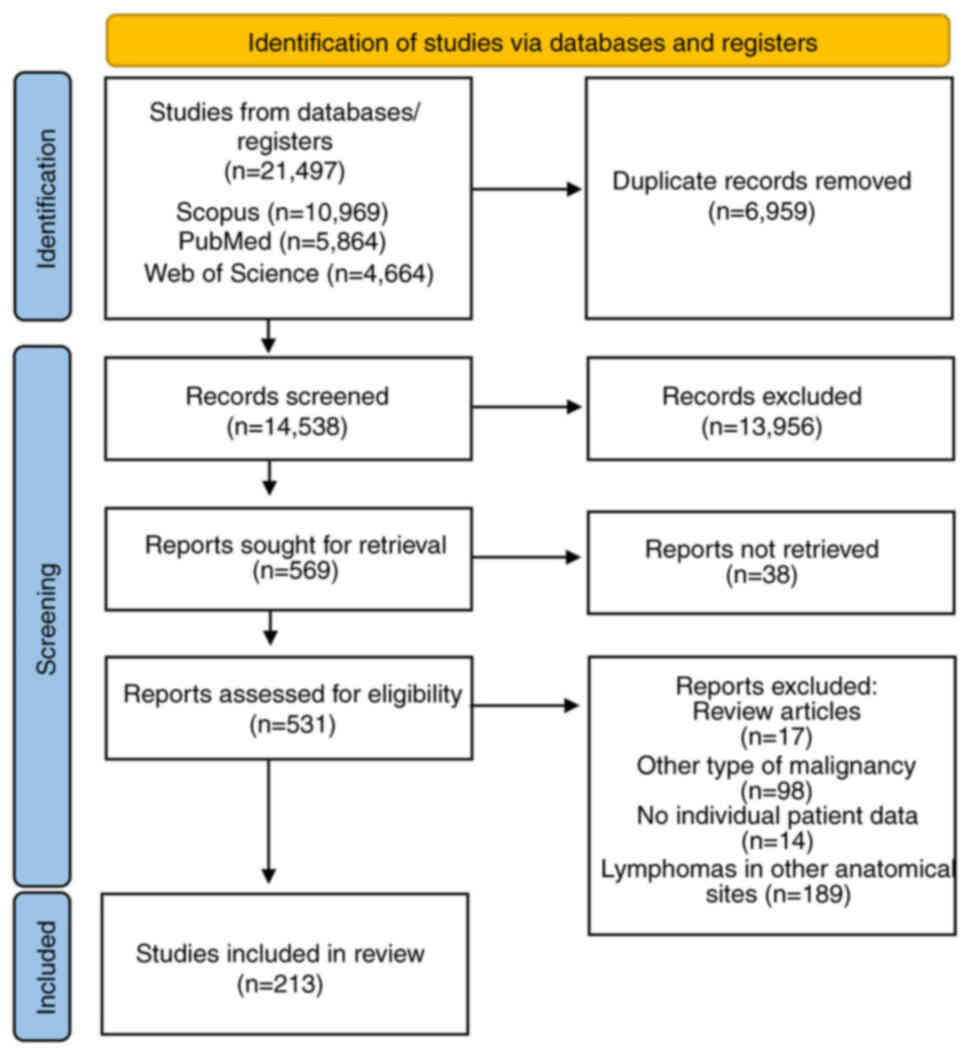

We identified 21,497 articles through the literature

search; 6,959 bibliographic references were removed as duplicates

and 13956 articles were excluded through title and abstract

screening as irrelevant. Two authors reviewed 569 full text

articles for eligibility. Finally, 213 studies, published between

1964 and 2023, were found eligible for the systematic review

(Figs. 1 and S1). Regarding continent, 84 of the

studies were conducted in Asia, 74 in Europe, 49 in Americas, 5 in

Africa and 1 in Oceania. In terms of design, 162 studies were case

reports and 51 were case series (Table

SI).

Patient characteristics

We identified a total of 339 cases of PLUC (Table SI). The mean age of the patients

was 48.5 years (median: 46, age range: 15–88). Data regarding

menopausal status was provided for 146 patients. For the remaining

cases menopausal status was based on the age. In total, 129

patients were classified as premenopausal (129/339, 38.1%) and 129

as postmenopausal (129/339, 38.1%) (Table SI).

Data regarding symptomatology was available for 318

cases. The most common presenting symptom was vaginal bleeding

(189/318, 59.4%) and its duration ranged from 4.5 days to 24

months. Vaginal bleeding was characterized in many cases as

post-coital (33/3018, 10.4%) or inter-menstrual (12/318, 3.8%). The

second most common symptom was vaginal discharge (44/318, 13.8%)

followed by abdominal pain (34/318, 107) and pelvic pain (12/318,

3.8%). A few patients remained asymptomatic (42/318, 13.2%) and

were diagnosed incidentally. Only a small fraction of patients

developed ‘B’ symptoms (28/318, 8.8%) including night sweats

(5/318, 1.5%), fever (9/318, 2.7%) and weight loss (14/318, 4.1%)

(Tables SI and SII).

Although all cases were confirmed by

histopathological examination, data regarding diagnostics was

provided for 278 patients. Biopsy (either excisional or punch

biopsy) was the most commonly used initial diagnostic modality

(78/278, 28.1%) followed by ultrasound (59/278, 21.2%), cervical

cytology (54/267, 20.2%) and computerized tomography (24/278,

8.6%). Data regarding histopathological types was available for all

cases. Among the 339 cases analyzed, the most common

histopathological subtype of PLUC was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(DLBCL) (39/339). Other predominant subtypes included non-Hodgkin's

B-cell lymphoma (13/339), large lymphoma (6/339), and intermediate

lymphoma (6/339). Less common but notable types observed were

lymphoma-like lesions (5/339) and several other rare subtypes,

reflecting the histopathological diversity within PLUC. Data for

histopathological markers was provided for 136 cases. The most

commonly encountered markers included CD3 (61/136, 44.9%), CD10

(48/136, 35.3%), CD20 (15/136, 11%) cyclin D1 (34/136, 25%), CD5

(29/136, 21.3%) and BCL-2 (16/136, 11.8%) (Table SI).

For staging the Ann Arbor system was used in 179

patients. The most common stages included stage I (93/179, 52%) and

stage II (47/179, 26.3%) followed by stage IV (29/179, 16.2%) and

stage III (8/179, 4.5%). FIGO staging for cervical cancer was also

utilized in 21 cases. The most common stages included FIGO stage I

(12/21, 57.1%), FIGO stage II (4/21, 19%), FIGO stage III (1/21,

4.8%) and FIGO stage IV (4/21, 19%). Data regarding the presence of

distant metastases at the time of diagnosis was provided for 245

patients with metastases being present in only a small fraction of

patients (26/245, 10.6%) mainly affecting retroperitoneal lymph

nodes and the kidney.

Information regarding management was provided for

309 patients (Table I). Almost one

third of the patients were managed surgically (115/309, 35.5%),

with most receiving adjuvant treatment (62/115), some receiving

surgery alone (34/115), and a few receiving neo-adjuvant treatment

(19/115). Of those that received surgery, the majority underwent

hysterectomy (85/115); which included radical hysterectomy (9/115),

total hysterectomy (58/85) and unspecified hysterectomy (18/85). A

small number of patients underwent hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy

(23/115). Of those that received neo-adjuvant treatment (19/115),

the majority received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (15/115), with a

very small fraction of those receiving ‘R-CHOP’ chemotherapy

(2/15), and the remaining receiving neo-adjuvant radiotherapy

(4/19). More than half of those that underwent surgery received

adjuvant treatment (62/115); the majority of this was chemotherapy

(35/62), with a small amount receiving ‘R-CHOP’ chemotherapy

(9/35), and the remainder receiving radiotherapy (18/62) or

chemo-radiotherapy (9/62) (Table

SIII).

| Table I.Median survival according to

therapeutic management type. |

Table I.

Median survival according to

therapeutic management type.

| A, Surgery |

|---|

|

|---|

| Management | n/N (%) | Median survival,

months (range) |

|---|

| Surgery | 115/309 (37.2) | 28 (1.5–228) |

| Surgery only | 34/309 (11.0) | 30 (6–204) |

| Hysterectomy | 85/115 (73.9) | 28 (2–228) |

| Hysterectomy and

lymphadenectomy | 23/115 (20.0) | 27 (4–108) |

| Radical

hysterectomy | 9/85 (10.6) | 26 (10–60) |

| Total

hysterectomy | 58/85 (68.2) | 28.5 (2–228) |

| Hysterectomy

(unspecified) | 18/85 (21.2) | 21.5 (3–204) |

| Embolisation | 3/115 (2.6) | 5.75 (1.5–10) |

| Surgery

(unspecified) | 14/115 (12.2) | 28 (6–156) |

|

| B, Neo-adjuvant

treatment |

|

|

Management | n/N (%) | Median survival,

months (range) |

|

| Neo-adjuvant | 19/115 (16.5) | 50 (8–156) |

| Chemotherapy | 15/19 (78.9) | 72 (36–156) |

| R-CHOP | 2/15 (13.3) | 96 (36–156) |

| Other

chemotherapy | 14/15 (93.3) | 72 (36–132) |

| Radiotherapy | 4/19 (21.1) | 33 (8–40) |

|

| C, Adjuvant

treatment |

|

|

Management | n/N (%) | Median survival,

months (range) |

|

| Adjuvant | 62/115 (53.9) | 18.5 (1.5–228) |

| Chemotherapy | 35/62 (56.5) | 17 (1.5–228) |

| R-CHOP | 9/35 (25.7) | 15 (4–48) |

| Other

chemotherapy | 26/35 (74.3) | 17 (1.5–228) |

| Radiotherapy | 18/62 (29.0) | 14 (2–60) |

|

Chemo-radiotherapy | 9/62 (14.5) | 54 (10–89) |

|

| D, Medical

treatment only |

|

|

Management | n/N (%) | Median survival,

months (range) |

|

| Medical only | 194/309 (62.8) | 24 (1–246) |

| Chemotherapy

only | 109/194 (56.2) | 23 (3–168) |

| Radiotherapy

only | 23/194 (11.9) | 36 (3–240) |

| Combination

therapy: Chemo-radiotherapy only | 62/194 (32.0) | 24 (1–246) |

The largest group of patients were managed without

surgery and received only medical therapies (194/309). This

comprised chemotherapy alone (109/194) with the commonest regime

being ‘R-CHOP’, followed by chemo-radiotherapy (62/194), and

radiotherapy (23/194).

Management trends

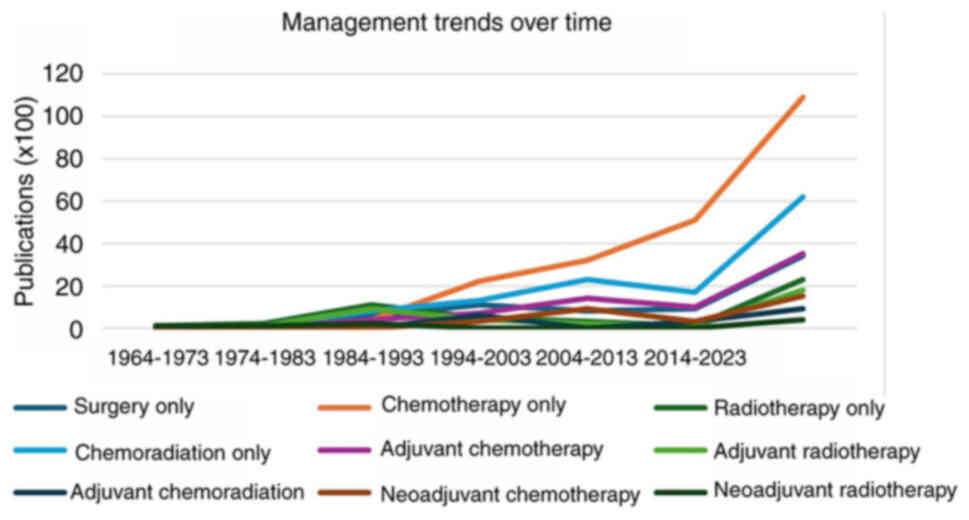

The majority of the cases with management data were

published later than 1984 (301/309). By decade, between 1984 and

present day, the proportion of patients treated with radiotherapy

decreased from 25% (11/44) in 1984–1993, to 1% (1/95) in the years

2014–2023. Conversely, the number of patients managed with

chemotherapy alone increased, from 9% (4/44) in the years

1984–1993, to 54% (53/95) in the most recent decade 2014–2023

(Fig. 2; Table SIV).

Outcome and survival rates

Data for clinical outcome was provided for 279

patients, of whom 46 died and 233 survived. Almost half of the

deaths occurred within 12 months after the initial diagnosis

(21/45, 46.6%). The follow-up period for survivors ranged from 4

weeks to 246 months and the absolute 5-year and 10-year survival

rates were 86.1 and 85.4%, respectively (Fig. 3A).

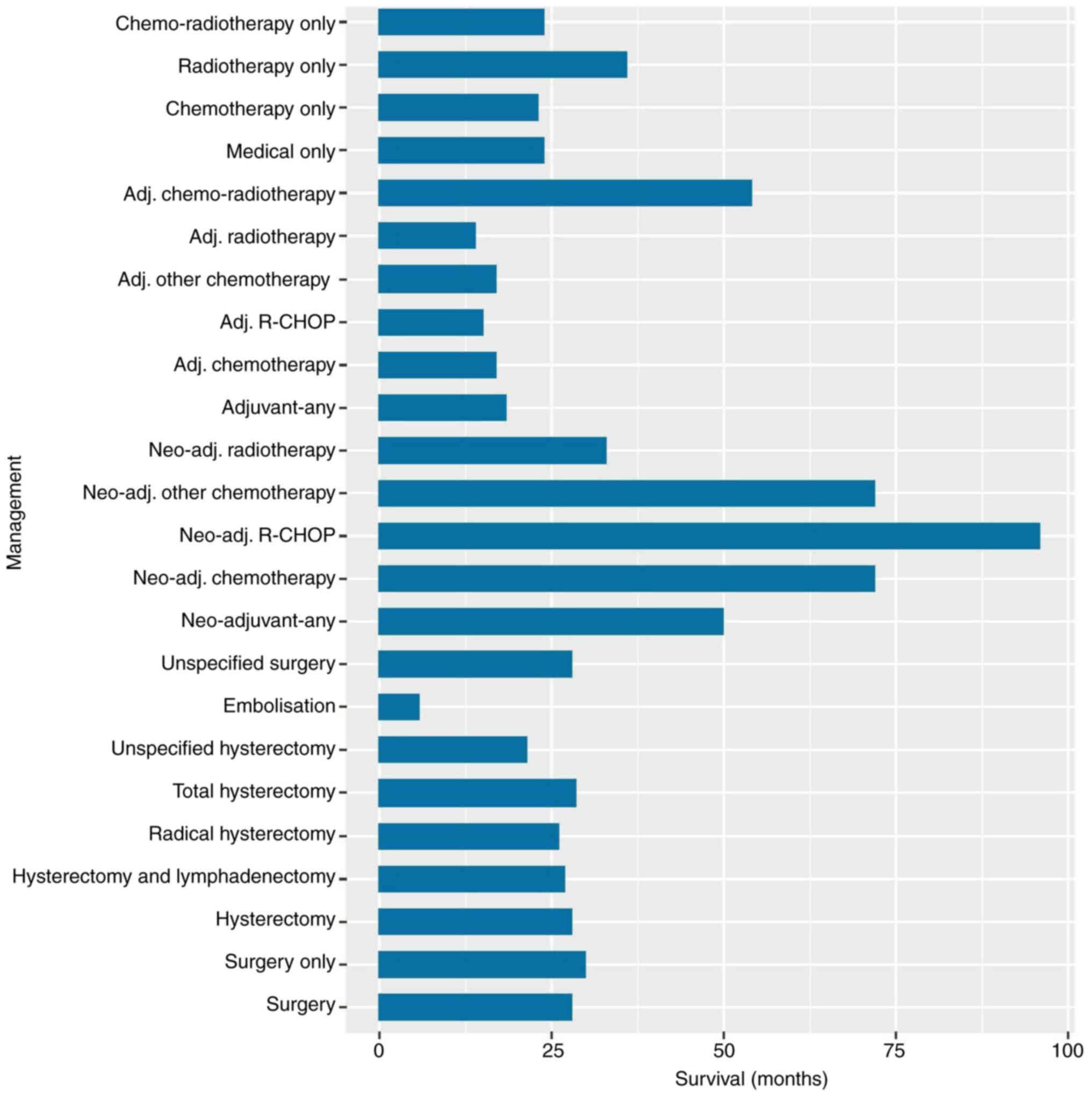

The longest median survival was for those that

received chemotherapy alone (72 months, range 36–156), and

particularly for the two patients that received neo-adjuvant

‘R-CHOP’ (96 months, range 36–156). The shortest median survival

was for the three patients that received uterine artery

embolization as treatment (5.75 months, range 1.5–10). Median

survival for those who received any surgery (28 months, range

1.5–228) was not dissimilar to those who received surgery alone (30

months, range 6–24), any medical therapy alone (24 months, range

1–246), including specifically chemotherapy alone (23 months, range

3–168), radiotherapy alone (36 months, range 3–240), or

chemo-radiotherapy (24 months, range 1–246). The type of

hysterectomy did not appear to affect median survival; with median

survival for radical hysterectomy (26 months, range 10–36)

calculated to be similar to those that underwent hysterectomy and

lymphadenectomy (27 months, range 4–108), total hysterectomy (28.5,

range 2–228), or any unspecified hysterectomy (21.5 months, range

3–204) (Table I).

Survival analysis indicated that premenopausal

patients exhibited better prognosis compared to postmenopausal

patients (P<0.0001) (Fig. 3B).

Moreover, surgical management with or without adjuvant/neoadjuvant

treatments was not superior to non-surgical management including

chemotherapy, radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy (P=0.29) (Fig. 2C). Additionally, we did not find

statistically significant differences in overall survival when we

compared surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy with chemotherapy alone

as well as surgery and adjuvant chemoradiation with chemoradiation

alone (Fig. S2; Table SIV). The presence of symptoms was

not associated with a reduced overall survival rate (P=0.24)

(Fig. 3D). The median survival and

ranges for each management type are presented in Table I and displayed in Fig. 4.

Quality of the studies

The quality assessment of the eligible studies

indicated that the majority of the included studies (138/204) met

most of the recommended criteria, categorizing them as having a low

risk of bias. In contrast, 64 studies were classified with a medium

risk of bias, while 2 studies fell into the high-risk category. A

total of 20 studies achieved a perfect score. The aspect most

frequently reported as ‘Not/Applicable’ among the studies was the

patient's past medical history (Table

SV, Table SVI, Table SVII). Sensitivity analyses were

performed using the log-rank test and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon

method while excluding potential confounding variables such as high

risk of bias studies, premenopausal women, and patients with stages

III and IV PLUC (Fig. S3, Fig. S4, Fig.

S5). The survival curves produced show late-stage crossover

which limits interpretation but have been included as part of

sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

In this systematic review of the literature, we

identified cases of primary lymphoma of the uterine cervix and

examined their clinicopathological characteristics, diagnosis and

therapeutic management. Our study included 213 reports which

comprised 339 patients diagnosed with primary lymphoma of the

uterine cervix. Our findings revealed that most patients presented

with non-specific symptoms including vaginal bleeding and discharge

with a mean age of 48.5. The menopausal status of the patients

varied and most of them were diagnosed at an early stage, according

to the Ann Arbor staging system. The follow-up period ranged from 4

weeks to 246 months and the absolute 5- and 10-year survival rates

were 86.1 and 85.4%, respectively. Although a higher concentration

of cases was noted in Asia and Europe in terms of geographical

distribution, the small volume of case reports and series analyzed

does not allow the identification of any geographical variations or

patterns. Broader studies on extranodal lymphomas suggest that

factors such as genetic predispositions, environmental influences,

or differences in healthcare systems and diagnostic practices may

contribute to regional distribution patterns (3).

The existence and recognition of primary genital

tract lymphomas was initially widely debated in the literature

(3) until the identification of

normal lymphoid tissue in female reproductive tract (17) and the reporting of patients with

malignant lymphomas located exclusively in gynecological organs

(18). While the exact causes and

mechanisms behind these lymphomas remain elusive, chronic

inflammation is suggested as a potential triggering factor

(19). However, further mechanistic

studies are required to elucidate the aforementioned theory. The

increase in the incidence of extra-nodal lymphomas in different

body sites, during the last decades has been also linked with the

increase in immunosuppressive therapies, environmental toxins as

well as, improved diagnostic techniques (20).

Despite the presence of published cases of primary

lymphomas of the female genital tract in the scientific literature

their definition remains a matter of controversy. A number of

investigators have discussed cases of lymphomas in different parts

of the female reproductive tract without presenting specific

criteria to define primary tumors (5,21–23).

Others have applied either the Fox and More criteria for uterine

lymphoma (24) or the Harris and

Scully modification of the Ann Arbor staging system for ovarian

lymphomas (25). Currently,

different staging systems are used for PLUC, which may contribute

to inconsistencies in diagnosis and treatment planning. Developing

a standardized staging and diagnostic framework specifically for

PLUC would reduce this variability and facilitate more consistent

management of the disease across clinical settings (26,27).

Regarding PLUC, the definition that has been proposed by Kosari

et al is the most comprehensive and includes the following

criteria: i) Lymphomas confined to the cervix at the time of

initial diagnosis, ii) lymphomas that are localized in the cervix

without any evidence of involvement of other body parts on full

investigation, and iii) the absence of abnormal cells indicating

leukemia in the peripheral blood and bone marrow (28).

The presentation of the disease usually involves

vaginal bleeding or discharge as cervical lesions can easily become

ulcerated and/or infected (29), a

phenomenon described in different histopathological types of

cervical malignancies (30). In

line with the results of our study, the presence of ‘B’ symptoms is

considered uncommon and affects only a relatively small number of

patients with PLUC (31), while

cases of asymptomatic patients have been also reported. Despite the

fact that clinical presentation of PLUC is very similar to other

cervical tumors, the disease is considered to be human

papillomavirus (HPV)-independent and distinct compared to cervical

epithelial malignancies (32–36).

While the co-existence of PLUC with other synchronous histological

types of cervical cancer is pathophysiologically feasible, in this

review, we only identified sporadic cases.

As far as diagnosis is concerned, histopathology

plays a pivotal role while cytology cannot be utilized reliably as

PLUC mainly affects the stroma rather than the epithelium of the

uterine cervix. This was also reflected in our results, with only

one fifth of the investigators using cytology as the first modality

for diagnosis. The histopathological diversity within PLUC, with

DLBCL as the most common subtype, mirrors patterns observed in

other extranodal lymphomas (27,37).

The range of subtypes suggests that while broad treatment protocols

may be effective, subtype-specific approaches may be beneficial for

optimizing outcomes. Less common subtypes, such as lymphoma-like

lesions, further underscore the need for careful diagnostic

differentiation, as histopathology plays a critical role in guiding

treatment decisions (38). Future

research should focus on identifying and characterizing genetic

profiles in PLUC, as this could lead to more tailored and effective

treatment options, similar to the advancements seen in other

lymphomas.

Immunohistochemistry is another important diagnostic

tool and lymphoma markers used for other types of lymphocyte

malignancies can be also found consistently in PLUC. These marker

include among others CD20 and Ki-67 for B-cell and CD3 and CD20 for

T-cell lymphomas (37). Although

such markers are widely used in diagnosing PLUC, variability in

their expression across cases can impact diagnostic accuracy. This

variability likely stems from the biological diversity of

lymphomas, with different lymphocyte subtypes displaying distinct

immunophenotypic profiles (26).

Genetic mutations and the tumor microenvironment also contribute to

these differences, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive

marker panel to improve accuracy (38).

In the analysis it was evident that premenopausal

women had better oncological outcomes when compared to the

postmenopausal women. Although such an outcome could have been

expected as premenopausal status could be associated with a

younger, healthier population, the actual reasons for this

disparity remain unclear. Potential factors may include differences

in hormonal status, comorbidities, or variations in treatment

response. Further research is necessary to investigate the

underlying mechanisms and how they may influence survival outcomes

in PLUC (38,39).

Due to the rarity of the disease, a consensus

regarding therapeutic management has not been established. Older

reports utilized radiotherapy as monotherapy. However, more recent

approaches included either surgery (115/309), with or without

neo-adjunctive or adjunctive therapy, chemotherapy alone (109/309),

or a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (62/310). In our

analysis, there was no statistically significant difference in the

overall survival when surgery alone was compared with chemotherapy

alone. However, the longest calculated median survival was for

those who received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (15 patients, median

survival 72 months, range 36–156). Additionally, surgery followed

by adjunctive chemotherapy resulted in similar overall survival

when compared to surgery alone. The question is whether PLUC should

be managed in accordance with treatment guidelines for lymphoma of

other sites (26), or whether it

should be site-specific; an anatomical site such as the uterine

cervix is feasible to remove surgically with relatively little

morbidity. Our study does not provide sufficient evidence to

confirm the idea that PLUC should be managed non-surgically. Based

on the extremely limited present data, which may also be influenced

by the age of some of the studies and geographical variation, there

is possibly a tentative suggestion that a combination of

neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and surgery may represent a reasonable

treatment option.

Current guidelines for the management of non-Hodgkin

lymphomas typically recommend chemotherapy as the first-line

approach. Specifically, for diffuse B-cell lymphomas, it is

preferable to utilize a doxorubicin-based regimen, such as a course

of six to eight cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide,

vincristine, prednisolone) (40).

In contrast, when dealing with indolent B-cell lymphomas, such as

marginal zone lymphomas, there is no single standardized regimen

that is universally recommended. Treatment options vary, ranging

from rituximab alone to more intricate and complex combinations

like R-hyper C-VAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and

dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine)

(41). The consideration of

radiotherapy as a treatment option is typically reserved for

instances of very low-stage lymphomas that exhibit localized

characteristics and can be easily targeted. For example, this

approach may be appropriate for early-stage follicular lymphoma, as

indicated in the NICE guidelines (42). Treatment guidelines for squamous

cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the cervix recommend surgery in

cases where the disease is at an early stage (43). In our study the overall survival was

not significantly different in patients treated with chemotherapy

alone. It is possible that chemotherapy alone represents a safe

treatment option for younger premenopausal patients diagnosed at an

early stage who wish to retain their fertility. Del Valle-Rubido

et al published the only case included in this study where

the patient received fertility-sparing management; a 28-year-old

woman received ‘CHOP’ chemotherapy, after transplantation of the

ovaries; this patient went on to survive at least 10 years and was

still alive at the time of writing (9). However, the results of our analysis in

this study, including the lack of difference in survival between

management options, should be interpreted with caution considering

the potential limitations associated with the analysis including

the low number of patients, the heterogeneity between the included

studies and the scarcity of events.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the most

comprehensive review on the reported cases of PLUC. Our findings

present pooled data from 328 patients and highlight published data

with quality assessment of included studies.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged.

The inclusion of low-quality case reports and case series limits

the validity and generalizability of our conclusions. These studies

inherently carry a significant risk of bias, being particularly

susceptible to overinterpretation and selection bias. Although many

of the studies were rated as low risk of bias according to our

assessment tool, their fundamental design flaws make them prone to

publication bias, especially since negative findings are rarely

reported. Consequently, the data presented, while potentially

insightful, may not accurately reflect real-world outcomes.

Additionally, although this study identifies various subtypes of

PLUC, the limited data available restricts our ability to

thoroughly examine the treatment response and prognosis for each

subtype, as also reflected in the lack of statistical power of the

Kaplan-Meier graphs. Given the rarity of PLUC and its subtypes,

further research is needed to understand these subtype-specific

outcomes, including recurrence rates and disease-free survival,

which may guide more tailored treatment strategies. Quality of life

metrics are also essential for providing insight into the impact of

PLUC treatments in the long-term. Therefore, data from larger,

prospectively designed studies are essential for drawing more

reliable conclusions about optimizing diagnostic and therapeutic

strategies for patients with PLUC.

A further limitation in the classification of PLUC

arises from the concurrent use of the Ann Arbor staging system,

which is traditionally used for lymphomas, and the FIGO staging

system, which is applied to cervical cancers. The use of these two

distinct staging systems can create inconsistencies and challenges

in classification, which may impact treatment decisions and hinder

efforts to further develop comparative studies. Developing a

unified staging system specifically tailored to PLUC could improve

clarity in both clinical practice and research, allowing for a more

standardized approach to diagnosis and treatment planning.

Another notable limitation is our inability to

estimate the effect size of outcomes and quantify uncertainty. It

is noteworthy that a majority of clinical cases lack sufficient

information for concentrating study results into a mean, median, or

proportion with a confidence interval. This underscores the

significance of initiatives aimed at standardizing and enhancing

the quality of information reported in case reports. Overall, a

pooled integrated analysis of case reports and series cannot

replace evidence provided by clinical trials. Therefore, subject

recruitment in rare diseases and personalized medicine represents a

critical task in clinical research (40,41,43,44).

Finally, the conclusions drawn from our integrated

analysis are inevitably constrained by the small number of patients

included, the difficulty to assess homogeneity between studies and

the inherent rarity of the events under investigation. Statistical

significance is typically determined by observing patterns or

outcomes that are unlikely to occur by chance alone (45). However, in the context of rare

events, the occurrence itself is infrequent, making traditional

measures of statistical analysis and significance less applicable.

The late crossover of survival curves observed in some of the

supplementary sensitivity analyses highlights a statistical

manifestation of this key limitation. Overall, the scarcity of

events can lead to challenges in sample size, limiting the

statistical power to detect meaningful differences or associations

(46–47).

In conclusion, malignant lymphomas can arise at

unconventional anatomical sites. In the cervix uteri, the tumor

appearance can vary and thus may be misdiagnosed with a primary

epithelial malignancy. Although primary malignant lymphomas of the

uterine cervix are infrequent, early detection, optimal therapeutic

management, and multidisciplinary involvement may provide benefits

to patients developing the disease. The knowledge of the rare

occurrence of malignant lymphoma in the cervix, its unique

characteristics and the increased awareness of clinicians can

prevent clinical misdiagnoses and ultimately improve the clinical

outcomes of patients developing this uncommon disease. While

evidence on this condition remains limited, leveraging

international registries could significantly strengthen the body of

knowledge surrounding this rare malignancy.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Joana Wagner, Dr

See Hyun Park, Dr Rachel Fitzpatrick, Dr Jorgen Kanters, Dr Irina

Tsibulak, Dr Barbara Chettle, Professor David Chettle, Dr Xingfeng

Li, Ms. Yuki Tokunaga and Mr. Srjdan Saso (Imperial College

Healthcare NHS Trust) for their help with manual translation from

Spanish (9), Polish (10,11)

and Japanese (12–15) into English.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization was performed by KSK. The main

aims were established by KSK, LBE, SJB and AS. Methodology was

performed by KSK, SB, LBE, SJB and AS, and validation by KSK, SB,

LBE, SJB, AS, SMS, IK, DL, FK, AM, AG, MP and MK. All aspects of

the investigation were performed by KSK, SB, LBE, SJB, AS, DL, FK,

AG and MP, specificlly this included protocol writing and

submission (KSK and SB), literature screening (KSK, SB, LBE and

SJB), data extraction (KSK, SB, LBE, SJB, AS, IK, DL, FK, AM, AG

and MP), risk of bias assessement (KSK, SB and SJB), and data

handling (SB, LBE, SJB, IK, DL, AM, AG and MP). Regarding

acquisition of resources, KSK, SB, LBE, SMS, SJB, AS, IK, DL, FK,

AM, AG and MP were responsible. Statistical analysis was performed

by KSK, SB, LBE, SJB and AS, and original draft preparation was

done by KSK, SB, LBE, SMS, SJB, AS, IK, DL, FK, AM, AG and MP.

Review and editing were performed by KSK, SB, LBE, SJB, AS, IK,

SMS, DL, FK, AM, AG, MP and MK, and visualization by KSK, SB, LBE,

SJB, AS, IK, SMS, DL, FK, AM, AG, MP and MK. KSK, LBE and MK

supervised the project, and KSK, LBE and MK were the project

administrators. KSK, SB, LBE, SJB, FK and AS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and patient consent

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Matasar MJ and Zelenetz AD: Overview of

lymphoma diagnosis and management. Radiol Clin North Am.

46:175–198. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Paquin AR, Oyogoa E, McMurry HS, Kartika

T, West M and Shatzel JJ: The diagnosis and management of suspected

lymphoma in general practice. Eur J Haematol. 110:3–13. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Freeman C, Berg JW and Cutler SJ:

Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer.

29:252–260. 1972. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chan JK, Loizzi V, Magistris A, Hunter MI,

Rutgers J, DiSaia PJ and Berman ML: Clinicopathologic features of

six cases of primary cervical lymphoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

193:866–872. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Harris NL and Scully RE: Malignant

lymphoma and granulocytic sarcoma of the uterus and vagina: A

clinicopathologic analysis of 27 cases. Cancer. 53:2530–2545. 1984.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shen H, Wei Z, Zhou D, Zhang Y, Han X,

Wang W, Zhang L, Yang C and Feng J: Primary extranodal diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma: A prognostic analysis of 141 patients. Oncol

Lett. 16:1602–1614. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hilal Z, Hartmann F, Dogan A, Cetin C,

Krentel H, Schiermeier S, Schultheis B and Tempfer CB: Lymphoma of

the cervix: Case report and review of the literature. Anticancer

Res. 36:4931–4940. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D,

Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P and Stewart LA; PRISMA-P Group,

: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ.

349:g76472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

del Valle-Rubido C, Cano-Cuetos A,

Heras-Sedano I, Marcos-González V, Marcos-González M and

Marcos-González A: Linfoma primario de cérvix: Gestación tras

tratamiento conservador Primary lymphoma of the cervix: Pregnancy

after conservative treatment. Progresos de Obstetricia y

Ginecología. 57:225–229. 2014.(In Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Plewicka M, Szelc S, Smok-Ragankiewicz A,

Wojcieszek A and Szkita D: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the uterine

cervix. Ginekol Pol. 66:246–248. 1995.(In Polish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Makarewicz R, Swirska M and Terlikiewicz

J: Non-hodgkin's malignant lymphoma in the uterine cervix. Wiad

Lek. 46:936–937. 1993.(In Polish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hashimoto A, Fujimi A, Kanisawa Y, Matsuno

T, Okuda T, Minami S, Doi T, Ishikawa K, Uemura N, Jyomen and

Tomaru U: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the uterine

cervix successfully treated with rituximabplus cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy-a case

report. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 40:2589–2592. 2013.(In Japanese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Isosaka M, Hayashi T, Mitsuhashi K, Tanaka

M, Adachi T, Kondo Y, Suzuki T and Shinomura Y: Primary diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma of the uterus complicated with

hydronephrosis. Rinsho Ketsueki. 54:392–396. 2013.(In Japanese).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Murotsuki J, Yazaki S, Hayakawa S and

Yamashita T: A case of malignant lymphoma of the uterine cervix.

Gan No Rinsho. 35:1716–1720. 1989.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ohkuma Y, Hachisuga T, Fukuda K and

Sugimori H: 23 Examination of lymphoma-like lesion of the uterine

cervix. Journal of the Japanese Society of Obstetrics and

Gynecology. 43:11331991.(In Japanese).

|

|

16

|

Joanna Briggs Institute, . Checklist for

Case Reports Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic

Reviews. Joanna Briggs Institute; Adelaide, Australia: 2019,

https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2021-10/Checklist_for_Case_Reports.docxFebruary

15–2024

|

|

17

|

Woodruff J, Castillo RN and Novak E:

Lymphoma of the ovary. A study of 35 cases from the ovarian tumor

registry of the American gynecological society. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 85:912–918. 1963. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Paladugu RR, Bearman RM and Rappaport H:

Malignant lymphoma with primary manifestation in the gonad: A

clinicopathologic study of 38 patients. Cancer. 45:561–571. 1980.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dursun P, Gultekin M, Bozdag G, Usubutun

A, Uner A, Celik NY, Yuce K and Ayhan A: Primary cervical lymphoma:

Report of two cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol.

98:484–489. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Trenhaile TR and Killackey MA: Primary

pelvic non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Obstet Gynecol. 97:717–720. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chorlton I, Norris H and King F: Malignant

reticuloendothelial disease involving the ovary as a primary

manifestation. A series of 19 lymphomas and 1 granulocytic sarcoma.

Cancer. 34:397–407. 1974. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Van de Rijn M, Kamel OW, Chang PP, Lee A,

Warnke RA and Salhany KE: Primary low-grade endometrial B-cell

lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 21:187–194. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Stroh EL, Besa PC, Cox JD, Fuller LM and

Cabanillas FF: Treatment of patients with lymphomas of the uterus

or cervix with combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Cancer. 75:2392–2399. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Fox H and More J: Primary malignant

lymphoma of the uterus. J Clin Pathol. 18:723–728. 1965. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Monterroso V, Jaffe ES, Merino MJ and

Medeiros LJ: Malignant lymphomas involving the ovary: A

clinicopathologic analysis of 39 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

17:154–1570. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES,

Pileri SA, Stein H and Thiele J: WHO Classification of Tumours of

Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. International Agency for

Research on Cancer. 2016.

|

|

27

|

Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P,

Weisenburger DD and Linet MS: Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO

subtype in the United States, 1992–2001. Blood. 107:265–276. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kosari F, Daneshbod Y, Parwaresch R, Krams

M and Wacker HH: Lymphomas of the female genital tract: A study of

186 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol.

29:1512–1520. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pretorius R, Semrad N, Watring W and

Fotheringham N: Presentation of cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

42:48–53. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kechagias KS, Zafeiri M, Katsikas

Triantafyllidis K, Kyrtsonis G, Geropoulos G, Lyons D, Burney Ellis

L, Bowden S, Galani A, Paraskevaidi M and Kyrgiou M: Primary

melanoma of the cervix uteri: A systematic review and meta-analysis

of the reported cases. Biology. 12:3982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Stabile G, Ripepi C, Sancin L, Restaino S,

Mangino FP, Nappi L and Ricci G: Management of primary uterine

cervix B-cell lymphoma stage IE and fertility-sparing outcome: A

systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel). 15:36792023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Intaraphet S, Farkas DK, Johannesdottir

Schmidt SA, Cronin-Fenton D and Søgaard M: Human papillomavirus

infection and lymphoma incidence using cervical conization as a

surrogate marker: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Hematol Oncol.

35:172–176. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kyrgiou M, Bowden S, Athanasiou A,

Paraskevaidi M, Kechagias K, Zikopoulos A, Terzidou V,

Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Bennett P and Paraskevaidis E: Morbidity

after local excision of the transformation zone for cervical

intra-epithelial neoplasia and early cervical cancer. Best Pract

Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 75:10–22. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kechagias KS, Kalliala I, Bowden SJ,

Athanasiou A, Paraskevaidi M, Paraskevaidis E, Dillner J, Nieminen

P, Strander B, Sasieni P, et al: Role of human papillomavirus (HPV)

vaccination on HPV infection and recurrence of HPV-related disease

after local surgical treatment: Aystematic review and

meta-analysis. BMJ. 378:e0701352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kechagias KS, Giannos P, Bowden S,

Tabassum N, Paraskevaidi M and Kyrgiou M: PCNA in cervical

intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer: An interaction

network analysis of differentially expressed genes. Front Oncol.

11:7790422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bowden SJ, Doulgeraki T, Bouras E,

Markozannes G, Athanasiou A, Grout-Smith H, Kechagias KS, Ellis LB,

Zuber V, Chadeau-Hyam M, et al: Risk factors for human

papillomavirus infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and

cervical cancer: An umbrella review and follow-up Mendelian

randomisation studies. BMC Med. 21:2742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cho J: Basic immunohistochemistry for

lymphoma diagnosis. Blood Res. 57:55–61. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Eichenauer DA, Aleman BM, André M,

Federico M, Hutchings M, Illidge T, Engert A and Ladetto M; ESMO

Guidelines Committee, : Hodgkin lymphoma: ESMO clinical practice

guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 29

(Suppl 4):iv19–iv29. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S,

Stein H and Jaffe ES: The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid

neoplasms and beyond: Evolving concepts and practical applications.

Blood. 117:5019–5032. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chaganti S, Illidge T, Barrington S, Mckay

P, Linton K, Cwynarski K, McMillan A, Davies A, Stern S and Peggs

K; British Committee for Standards in Haematology, : Guidelines for

the management of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol.

174:43–56. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cibula D, Raspollini MR, Planchamp F,

Centeno C, Chargari C, Felix A, Fischerová D, Jahnn-Kuch D, Joly F,

Kohler C, et al: ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of

patients with cervical cancer-Update 2023. Virchows Arch.

482:935–966. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence, . Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Updated guidelines.

2023.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng52/resources/nonhodgkin-lymphoma-pdf-3306777546949March

8–2024

|

|

43

|

Frieden TR: Evidence for health decision

making-beyond randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med.

377:465–475. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Board PATE: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment

(PDQ®). PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. National

Cancer Institute; 2023

|

|

45

|

Friede T, Posch M, Zohar S, Alberti C,

Benda N, Comets E, Day S, Dmitrienko A, Graf A, Günhan BK, et al:

Recent advances in methodology for clinical trials in small

populations: The InSPiRe project. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 13:1862018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lane PW: Meta-analysis of incidence of

rare events. Stat Methods Med Res. 22:117–1132. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cai T, Parast L and Ryan L: Meta-analysis

for rare events. Stat Med. 29:2078–2089. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|