Introduction

Schwannomas, also referred to as neurilemmomas, are

the most common type of benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor

(BPNST), originating from Schwann cells and present predominantly

in the hands and upper limbs (1–4). While

PNSTs are rare, schwannomas are the most prevalent type, accounting

for nearly 5% of all soft-tissue tumors of the upper limb (5). The global incidence of schwannomas is

reported to be 3–4 cases per million individuals (6). As BPNSTs, schwannomas typically grow

slowly, with a relatively low incidence of malignant

transformation, generally ranging from 1 to 13% (7). Therefore, the prognosis for the vast

majority of patients is favorable, and the mortality rate is

relatively low. However, for patients at risk of malignant

transformation, especially those with pathogenic genes (such as

NF2, SMARCB1 and LZTR1), there may be a higher risk of

complications (8). Approximately

19% of all cases of schwannomas occur in the upper limb, with the

distal region near the elbow being the most common tumor site

(9). These tumors tend to originate

along major nerves and on the flexor surfaces of the upper and

lower limbs (10,11). Surgical intervention has been

reported as the primary treatment and is relatively effective for

schwannomas (12). However, to the

best of our knowledge, studies on multiple schwannomas in the upper

limb are scarce. The rarity of this condition and the ambiguity in

the diagnostic criteria may lead to an underestimation of the

actual incidence of multiple schwannomas. Therefore, it is

imperative to conduct standardized studies on multiple schwannomas

in the upper limb, including studies on diagnosis, surgical

management and postoperative care. In this context, the present

study discusses the case of a patient with multiple schwannomas in

the upper limb. This report also includes a brief review of the

literature on the pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis and

treatment of schwannomas, with the objective of providing novel

insights into their management.

Case report

A 70-year-old man presented at Guangzhou Red Cross

Hospital (Guangzhou, China) in January 2024 with a mass in the left

upper limb that had existed for >40 years. Initially, this mass

was solid and oval in shape, measuring ~1×2 cm on the medial aspect

of the left upper limb. No specific treatment was received for the

mass. Over the past 20 years, the mass had progressively enlarged,

and new masses have developed near the left elbow and the

hypothenar region. The patient reported no pain or tenderness, and

all the masses were cystic-solid upon palpation. The results of the

neurological examination were unremarkable. The masses were mobile

in the transverse plane but not along the longitudinal axis. The

overlying skin exhibited no signs of redness, swelling or

ulceration, and no increase in skin temperature was noted. No

family member had a history of schwannomas. Given these

observations, it was plausible to conclude that this case was more

likely to represent a sporadic schwannoma.

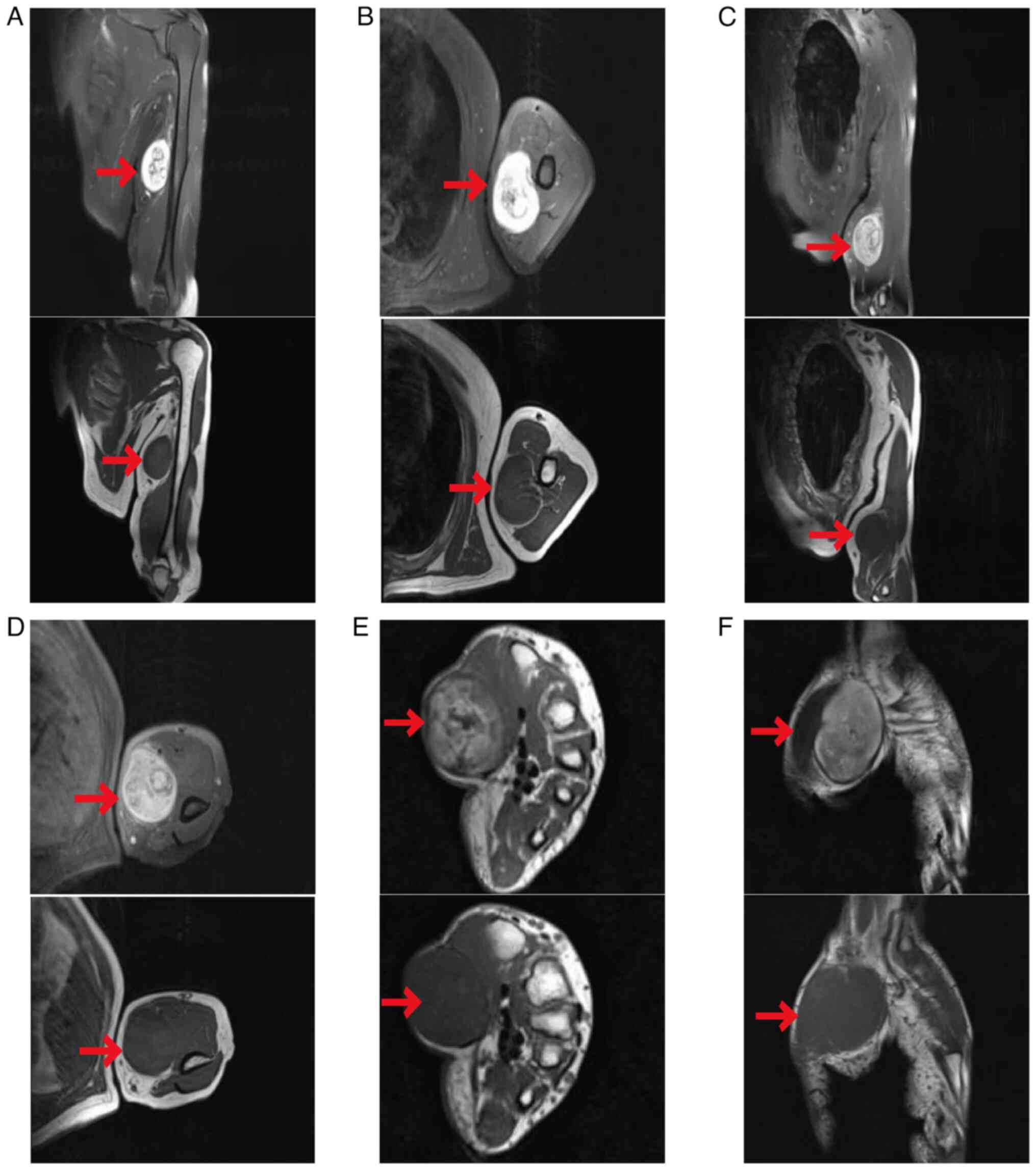

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination

conducted upon admission revealed two ovoid masses located in the

ulnar nerve path in the middle to distal part of the left upper

arm, with slight hyperintensity on T1-weighted images and

heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighted images. The masses were

~4.2×5.8×6.1 and 5.0×5.6×6.5 cm in size. The T2-weighted images

revealed target signs, with the masses closely related to the

nerve. No signal suppression was noted on fat-saturated sequences,

and the enhancement of the masses was heterogeneous, with

progressive enhancement on delayed-phase imaging. The adjacent

muscles exhibited signs of compression displacement with distinct

delineations. In addition, long ovoid nodular lesions with similar

signal characteristics were observed on the radial side of the

flexor tendon sheath close to the wrist and superficial to the

thenar muscles on the volar aspect of the left forearm. These

lesions were ~1.4×2.8 and 3.0×3.7×5.1 cm in size, respectively, and

exhibited marked heterogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced

images (Fig. 1).

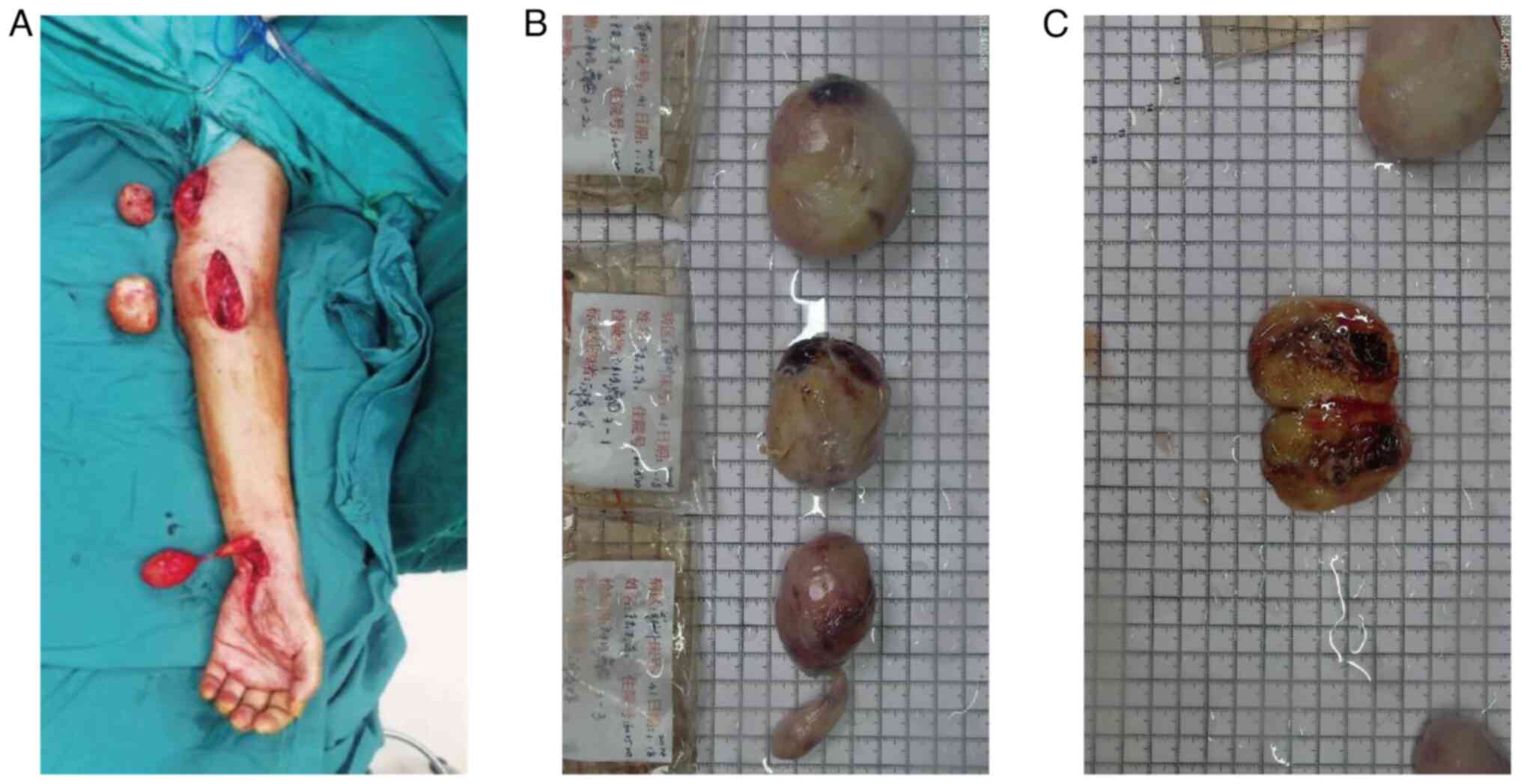

The patient underwent excision of the left upper

limb mass, median nerve exploration and pathological biopsy under

general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. A longitudinal

incision was made along the long axis of the tumor, followed by an

incision on the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The tumor was bluntly

dissected and exposed. A capsule was observed, although it was a

focal discontinuity. The tumor adhered to the surrounding skeletal

muscle and the median nerve, which was most consistent with a

benign neurogenic tumor. Careful dissection of the surrounding

nerves, blood vessels and tendons was performed. The tumor

dimensions from proximal to distal were 6×5×3, 5×4×3.5 and 5×3.5×3

cm, respectively (Fig. 2). The

incision was closed in layers, and the tumors were sent for

pathological evaluation. The postoperative course remained

uneventful, and complete tumor resection was achieved without any

damage to the surrounding nerves. The patient exhibited no sensory

or circulatory abnormalities in the surgical region or the distal

limb, and no complications occurred. The patient was, therefore,

discharged with a healed incision.

Postoperative pathological examination revealed the

following gross findings: i) Subcutaneous mass no. 1 in the left

upper limb: A grayish-red to grayish-white mass measuring 6×5×3 cm,

with the excised surface exhibiting grayish-red to grayish-white

coloration and soft consistency. ii) Subcutaneous mass no. 2 in the

left upper limb: A grayish-red to grayish-white mass measuring

5×4×3.5 cm in size, with the excised surface exhibiting grayish-red

to grayish-yellow coloration, a moderate texture and associations

with regions of hemorrhage. iii) Subcutaneous mass no. 3 in the

left upper limb: A grayish-red mass measuring 5×3.5×3 cm, with a

tail 5 cm in length and ~1 cm in diameter, exhibiting a grayish-red

to grayish-yellow excised surface with a soft consistency and solid

texture. After tissue sampling, fixation with 10% neutral formalin

at room temperature for 8 h, dehydration, embedding with paraffin,

sectioning at a thickness of 4 µm and staining, the prepared slides

were examined under a Nikon Eclipse CI optical microscope (Nikon

Corporation). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was

performed on the prepared slides. After dewaxing and rehydrating at

room temperature, the slides were stained with hematoxylin for 3

min, differentiated and rinsed before being stained with eosin for

9 min. Following rinsing, dehydration and clearing, the slides were

baked at 67°C for 15 min, dried for 10 min and then mounted for

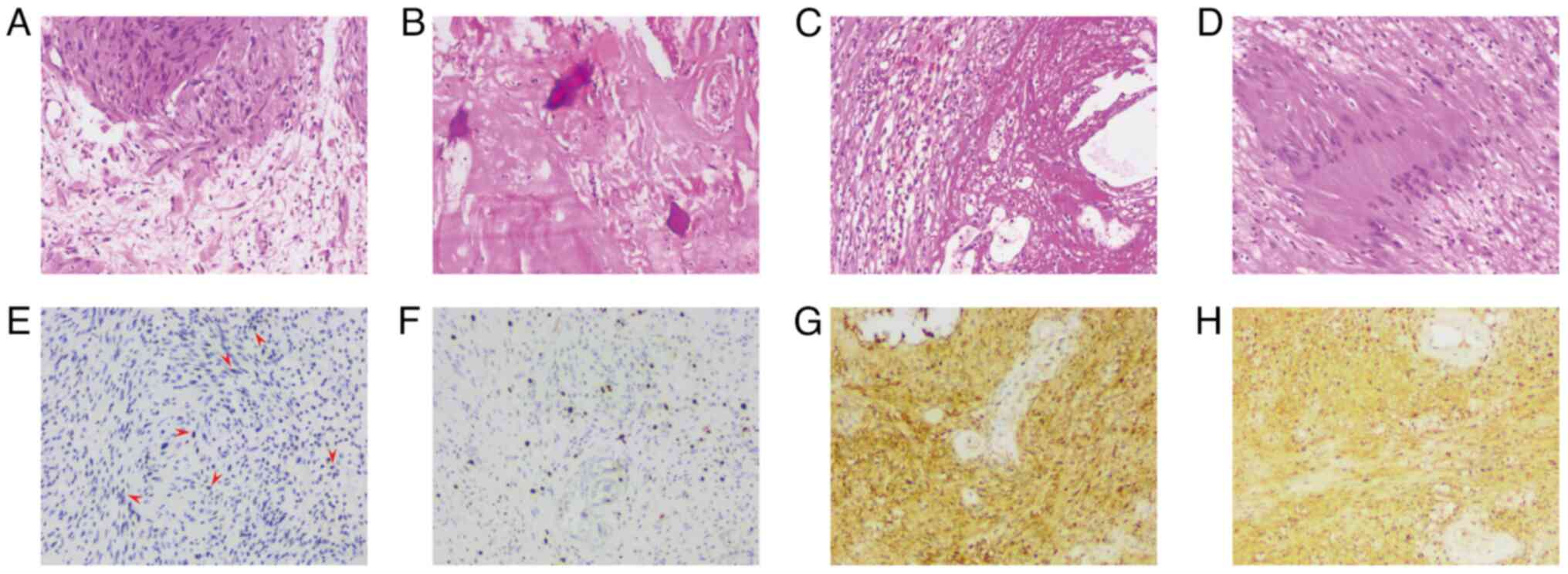

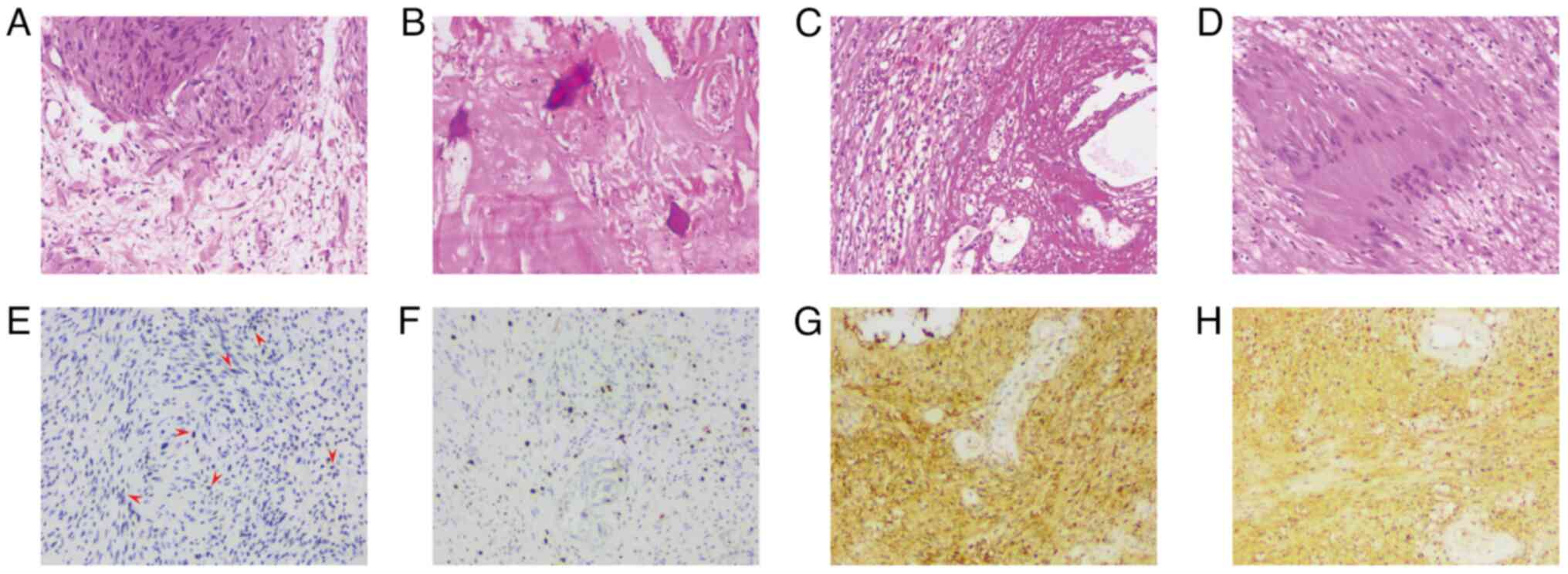

observation. H&E staining revealed typical fascicular regions

(Antoni A regions) and reticular regions (Antoni B regions). The

Antoni A regions contained spindle-shaped cells arranged in

fascicular and palisading patterns, with Verocay bodies, with a few

regions densely packed, while other regions were more loosely

arranged, with visible blood vessels. The Antoni B regions

presented with hemosiderin deposition around the blood vessels,

along with chronic hemorrhage and cystic changes, suggesting a

degenerative schwannoma. Mild nuclear atypia (degenerative changes)

was observed in some cells, with no increased mitotic activity. The

stroma showed loose myxoid changes, with abundant vascular

structures exhibiting congestion and hemorrhage, accompanied by

fibrosis, hyaline degeneration and localized calcification,

indicating a degenerative schwannoma (Fig. 3A-D). To accurately describe the

tumor components, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed

on several representative paraffin block sections using the

ChemMate Envision method (DakoCytomation; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). IHC was performed using a ready-to-use ChemMate Envision kit

from DakoCytomation; Agilent Technologies, Inc., [Kit details:

Anti-p53 (DO-7) monoclonal antibody, cat. no. M7001; anti-Ki-67

(30–9) rabbit monoclonal primary antibody, cat. no. 790-4286; S100

antibody, cat. no. CSM-0101] following the manufacturer's

instructions. The immunohistochemistry analysis revealed positive

expression for S100, p53 (~2%) and Ki-67 (hotspot region ~2%).

S-100 immunohistochemical staining showed positivity in both the

cytoplasm and nuclei of tumor cells, with some regions primarily

exhibiting cytoplasmic positivity, while others demonstrated both

cytoplasmic and nuclear dual positivity, suggesting that the latter

may indicate higher tumor activity. p53 immunohistochemical

staining demonstrated focal positivity in scattered tumor cells

with variable staining intensity, showing colors ranging from light

to dark brown. Immunohistochemical staining revealed a Ki-67

proliferation index of 2%, indicating the presence of tumor cells

(Fig. 3E-H). Based on the

histological morphology of schwannomas in the microscopic

examination section of the third edition of ‘Diagnostic Pathology:

Soft Tissue Tumors’ (13), the

pathological diagnosis was established as multiple schwannomas of

the left upper limb with secondary degenerative hemorrhage. During

the 1-year postoperative follow-up period, the patient underwent

seven clinical examinations. The surgical wounds healed well

without significant complications, and physical examinations

revealed no evidence of tumor recurrence.

| Figure 3.Tumor H&E and immunohistochemistry

staining. (A-D) H&E staining and (E-H) immunohistochemical

staining images of schwannomas (all ×100 magnification). (A) The

diagnostic morphology of the schwannoma revealed typical fascicular

regions (Antoni A regions) and reticular regions (Antoni B

regions). The Antoni A regions contained spindle cells arranged in

fascicles or interwoven patterns, and Verocay bodies were also

observed; the lower region exhibited a loose pattern, with visible

blood vessels. (B) Noticeable hyaline degeneration of the tumor

stroma and punctate calcification were present, indicating a

degenerative schwannoma. (C) The Antoni B region presented with

hemosiderin deposition around the blood vessels, along with chronic

hemorrhage and cystic changes, suggesting a degenerative

schwannoma. (D) Antoni A regions exhibited spindle cells in

fascicular or interwoven arrangements, and Verocay bodies were

present. (E) p53 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated focal

positivity in scattered tumor cells with variable staining

intensity. Red arrows point to some of these positively stained

cells or cell clusters, which are colored in varying shades from

light to dark brown. (F) Immunohistochemical staining revealed a

Ki-67 proliferation index of 2%, indicating the presence of tumor

cells. (G and H) Immunohistochemical staining for S-100 revealed

positivity in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the tumor cells.

Cytoplasmic positivity is mainly shown in (G), while (H) exhibits

both cytoplasmic and nuclear dual positivity, suggesting that the

latter may indicate higher tumor activity. H&E, hematoxylin and

eosin. |

Discussion

Schwannomas are non-invasive tumors of the

peripheral nerve sheath. Studies have indicated that schwannomas

are the most common PNSTs in the upper limb, with an incidence rate

of 64% (12). No significant sex or

ethnicity differences have been noted in this context (14). In a 22-year epidemiological study

conducted by Sandberg et al (12), which studied a total of 68 tumors in

53 patients, the median nerve was revealed to be the most

frequently affected nerve, followed by the ulnar and digital

nerves.

Research has shown that schwannomatosis and

neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) are both characterized by multiple

schwannomas but represent distinct genetic entities. NF2 is caused

by mutations in the NF2 gene, whereas schwannomatosis is associated

with germline mutations in SMARCB1 or LZTR1 (15). In the epidemiological study on

schwannomas by Forde et al (16), the prevalence of LZTR1-related

schwannomatosis and SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis was ~1 in

527,000 and ~1 in 1,100,000, respectively, which is 8.4 to 18.4

times lower than the prevalence of NF2. This highlights the

significant role of NF2 in the genetic diagnosis of schwannomas

(17). In the present case, due to

the need for outsourcing high-throughput sequencing, the associated

costs and the patient's personal preferences, genetic sequencing

could not be performed to confirm the presence of any alterations

in the NF2 gene.

The clinical presentation of schwannomas varies

notably. Certain reports indicate that these tumors may be

painless, although this lack of pain may be attributed to their

slow growth, indirect compression of the nerve and absence of

sensory innervation in the tumor (18–21). A

comprehensive retrospective analysis by Iwashita, which examined

1,202 patients with 1,271 schwannomas, demonstrated a notably low

incidence of pain. The histopathological classification of the

patients revealed several distinct types: Common (n=932),

degenerative (n=238), cellular (n=19), plexiform (n=35), pigmented

(n=2), myxoma (n=16) and organoid (n=30), with pain manifestation

predominantly observed in myxoma and organoid variants (19). Additionally, symptoms such as pain,

sensory abnormalities and a positive Tinel's sign are often

associated with the location of the tumor. As the tumor grows and

compresses more sensitive nerve regions, the patient may experience

pain or other symptoms. A review of the literature on patients with

schwannomas in the hand and wrist revealed that the interval

between symptom onset and surgery ranged from a few months to 37

years (14). Tumors located in the

finger regions tend to cause symptoms earlier than those located in

the wrist and the palm. In the present case, the combination of the

patient's 40-year clinical history and subsequent histopathological

findings from H&E staining strongly indicated a degenerative

variant of schwannoma (19).

When considering differential diagnoses, it is

important to identify benign tumors that could be confused with

schwannomas. The tumors that should be distinguished from

schwannomas include neurofibromas, neuroblastomas and

ganglioneuromas. Clinically, no distinct standard exists for

differentiating schwannomas from neurofibromas. However, the

literature suggests that the primary distinction between the two

lies in the age of the patients in which they occur, as while

neurofibromas predominantly originate in individuals aged 20–30

years, schwannomas are more common in those aged 30–50 years

(12,14). Nevertheless, distinguishing

schwannomas from other tumors based solely on clinical history and

imaging findings remains considerably challenging.

Ultrasound examination may be utilized to establish

a preoperative diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors in the extremities.

According to reports, an accuracy rate of up to 77% may be achieved

when ultrasound is used as an initial diagnostic modality (22). Ultrasound, however, is unable to

differentiate between schwannomas and other tumors, as all tumors

typically present as similar hypoechoic masses with posterior

acoustic enhancement. Typically, uncharacterized soft-tissue masses

in the upper limb that are suspected to be related to PNSTs require

further evaluation through MRI examination, which reportedly has

75% diagnostic accuracy in the case of these tumors (23). Schwannomas typically present a

homogeneous central low signal and a peripheral high signal,

referred to as the target sign, although this is not exclusive to

schwannomas (22). While MRI is

more accurate for determining tumor location and establishing the

differential diagnosis of schwannomas, it does not achieve 100%

diagnostic accuracy. In addition, fine-needle aspiration or open

biopsy is unsuitable for a definitive diagnosis, as these

procedures may lead to scarring and potential fascicular injury

during subsequent excision (11).

Therefore, despite the availability of appropriate clinical and

imaging evidence, the definitive diagnosis of schwannomas continues

to rely on histopathological examination.

Currently, no pharmacological therapies are

recommended as alternatives to surgery for the treatment of

schwannomatosis (24). In

asymptomatic schwannomas that are stable in size, a period of

observation may be appropriate. In the management of benign

schwannomas, therapists prefer to perform complete excision of the

tumor along with its capsule, as recurrence is often observed in

different regions of the same nerve in the affected limb rather

than at the surgical site (25).

The optimal surgical approach involves microsurgical techniques for

intralesional dissection and meticulous tumor removal aimed at

preserving nerve structures while minimizing traction on the

surrounding nerve bundles (2,14,26,27).

Overall, a review of the relevant literature and the

findings of the present case indicate that patients with

schwannomas commonly present with soft-tissue masses, which may be

accompanied by symptoms that develop due to nerve compression.

Schwannomas originate from Schwann cells located within the nerve

sheath and are often easily separable from the nerve. The present

report highlights the fact that schwannomas can be multifocal and

affect different regions of the body. A thorough examination of the

peripheral nerves in patients with schwannomas is therefore

essential, and a complete dissection should be performed to obtain

a biopsy and thereby confirm that the tumor is not malignant. The

potential for tumor recurrence underscores the necessity for

routine follow-up examinations of affected patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Yanmei Li

(Department of Radiology, Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital, Guangdong,

China) for providing radiography consultations.

Funding

This research was supported by the Guangzhou Science and

Technology Program of Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital (grant no.

202102010111) and the Guangzhou Municipal Key Discipline in

Medicine.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DY conceived and designed the study, and revised the

manuscript. HC collected and analyzed the patient's clinical,

imaging and pathological data, and drafted the manuscript. XY and

PW performed the surgeries, provided detailed surgical

descriptions, and contributed to the refinement of the manuscript's

conception, design and content. WY, YL, WL, YT, and JL contributed

to the writing of specific sections of the manuscript, assisted in

the development of the study's methodology, analyzed data and

prepared the pathological images for analysis. YX and HM

contributed to the overall study design, critically reviewed the

manuscript for important intellectual content, and oversaw the

processing and presentation of the figures. YY independently

analyzed the radiological images, identified key diagnostic

features and drafted the radiological findings section of the

manuscript. LL performed the histopathological examination,

conducted the immunohistochemical staining, interpreted the results

and drafted the pathology section of the manuscript. HC, XY, PW and

DY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript, and have agreed to be

accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions

related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are

appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided specific written informed

consent for publication, which included the acquisition of clinical

data and images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hsu CS, Hentz VR and Yao J: Tumours of the

hand. Lancet Oncol. 8:157–166. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lai CS, Chen IC, Lan HC, Lu CT, Yen JH,

Song DY and Tang YW: Management of extremity neurilemmomas:

Clinical series and literature review. Ann Plast Surg. 71 (Suppl

1):S37–S42. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Longhurst WD and Khachemoune A: An unknown

mass: The differential diagnosis of digit tumors. Int J Dermatol.

54:1214–1225. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Payne WT and Merrell G: Benign bony and

soft tissue tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 35:1901–1910. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Holdsworth BJ: Nerve tumours in the upper

limb A clinical review. J Hand Surg. 10:236–238. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Petrov M, Sakelarova T and Gerganov V:

Other nerve sheath tumors of brain and spinal cord. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1405:363–376. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Junxiao G and Qianhui Q: Diagnosis and

surgical treatment of head and neck Schwannomas. Intern J

Otolaryngol-Head and Neck Surg. 43:216–219. 2019.(In Chinese).

|

|

8

|

Magro G, Broggi G, Angelico G, Puzzo L,

Vecchio GM, Virzì V, Salvatorelli L and Ruggieri M: Practical

approach to histological diagnosis of peripheral nerve sheath

tumors: An update. Diagnostics (Basel). 12:14632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD, Strong EW and

Hajdu SI: Benign solitary Schwannomas (neurilemomas). Cancer.

24:355–366. 1969. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kang HJ, Shin SJ and Kang ES: Schwannomas

of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Br. 25:604–607. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Russell SM: Preserve the nerve:

Microsurgical resection of peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

Neurosurgery. 61 (3 Suppl):S113–S117; discussion 117–118. 2007.

|

|

12

|

Sandberg K, Nilsson J, Soe Nielsen N and

Dahlin LB: Tumours of peripheral nerves in the upper extremity: A

22-year epidemiological study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand

Surg. 43:43–49. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lindberg M: Diagnostic Pathology: Soft

Tissue Tumors. 3rd Edition. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2019

|

|

14

|

Ozdemir O, Ozsoy MH, Kurt C, Coskunol E

and Calli I: Schwannomas of the hand and wrist: Long-term results

and review of the literature. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong).

13:267–272. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Kluwe L, Friedrich RE,

Summerer A, Schäfer E, Wahlländer U, Matthies C, Gugel I,

Farschtschi S, Hagel C, et al: Phenotypic and genotypic overlap

between mosaic NF2 and schwannomatosis in patients with multiple

non-intradermal schwannomas. Hum Genet. 137:543–552. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Forde C, Smith MJ, Burghel GJ, Bowers N,

Roberts N, Lavin T, Halliday J, King AT, Rutherford S, Pathmanaban

ON, et al: NF2-related schwannomatosis and other schwannomatosis:

An updated genetic and epidemiological study. J Med Genet.

61:856–860. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kim BH, Chung YH, Woo TG, Kang SM, Park S,

Kim M and Park BJ: NF2-related schwannomatosis (NF2): Molecular

insights and therapeutic avenues. Int J Mol Sci. 25:65582024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Khodaee M and Langston L: A painless

finger mass. J Musculoskel Neuron. 12:189–191. 2012.

|

|

19

|

Iwashita T: Neurilemmoma of the soft

tissues: An analysis of 1,271 tumors in an attempt at subtyping.

Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 80:355–367. 1989.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Martin AE, Martin D, Sandu AM, Neacsu A,

Rata O, Gorgan C and Gorgan MR: Nerve sheath tumor, benign

neurogenic slow-growing solitary neurilemmoma of the left ulnar

nerve: A case and review of literature. Rom Neurosur. 30:219–229.

2016.

|

|

21

|

Pinho R, Santana S, Farinha F, Cunha I,

Barcelos A and Brenha J: Shoulder giant schwannoma-a diagnosis to

be considered in painless shoulder masses. Acta Reumatol Port.

42:332–333. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hung YW, Tse WL, Cheng HS and Ho PC:

Surgical excision for challenging upper limb nerve sheath tumours:

A single centre retrospective review of treatment results. Hong

Kong Med J. 16:287–291. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nilsson J, Sandberg K, Soe Nielsen N and

Dahlin LB: Magnetic resonance imaging of peripheral nerve tumours

in the upper extremity. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg.

43:153–159. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Plotkin SR, Blakeley JO, Evans DG,

Hanemann CO, Hulsebos TJ, Hunter-Schaedle K, Kalpana GV, Korf B,

Messiaen L, Papi L, et al: Update from the 2011 International

Schwannomatosis Workshop: From genetics to diagnostic criteria. Am

J Med Genet A. 161A:405–416. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Spinner RJ: Complication avoidance.

Neurosurg Clin N Am. 15:193–202. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Huang X, Peng C, Yorkashjan M, Li Y, Kong

W, Maimaitiali T and Zhao Y: Microscope-assisted treatment of rare

schwannoma of median nerve: 1 case. J Pract Hand Surg. 35:543–544.

2021.

|

|

27

|

Maimaitiali T, Kong W, Huang X, Peng C, Li

Y and Zhao Y: Microscopic technique in the treatment of proximal

thenar ulnar schwannoma in 1 case. J Pract Hand Surg. 36:569–570.

2022.(In Chinese).

|