According to data from the 2024 National Cancer

Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the

age-standardized incidence rate of breast cancer for women during

the 2017–2021 period was 131.8 per 100,000 women. Triple-negative

breast cancer (TNBC) is a highly heterogeneous subtype of breast

cancer with poor prognosis, accounting for 10–20% of all breast

cancer cases and having the lowest survival rate (78%) among all

subtypes (1). Due to the lack of

expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), TNBC is insensitive to

traditional hormone therapy and targeted treatments, leaving

chemotherapy as the primary treatment option for TNBC. However, the

high rates of recurrence and metastasis in TNBC highlight the

urgent need to identify novel therapeutic strategies and molecular

targets to improve patient survival (2).

The primary risk factor for breast cancer is a

mutation in either of the breast cancer susceptibility genes breast

cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA)1 or BRCA2. A considerable

proportion of patients with TNBC carry germline BRCA1/2 mutations.

Tumors harboring BRCA1/2 mutations are highly dependent on poly

(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) proteins, which are essential for

repairing single-strand DNA damage through the base excision repair

pathway (3). Consequently, PARP

inhibitors, due to their unique mechanism of blocking DNA damage

repair, are particularly suited for treating tumors with DNA repair

deficiencies (4). Over the past

decades, PARP inhibitors have emerged as promising drugs in

clinical oncology (5,6).

To date, numerous clinical research articles have

been published on PARP inhibitors in the treatment of breast

cancer, ovarian cancer and other diseases. At present, there are

eight PARP inhibitors, of which only six have been approved for

global marketing, excluding Iniparib and Veliparib. These approved

drugs include Olaparib (NCT02734004), Rucaparib (NCT02042378),

Niraparib (NCT05734911), Talazoparib (NCT04987931), Fuzuloparib

(NCT05753826) and Pamiparib (NCT03333915) (7–9), and

are used for the treatment of ovarian cancer (such as NCT03333915),

pancreatic cancer (such as NCT02677038), breast cancer (such as

NCT01074970), prostate cancer (such as NCT03516812) and other solid

tumors (10).

It is worth noting that not all PARP inhibitors have

achieved highly satisfactory results in the treatment of breast

cancer due to the emergence of drug resistance, toxic side effects,

such as bone marrow suppression and gastrointestinal discomfort, as

well as limitations in the target population (e.g., the efficacy of

the drug depends on the BRCA gene mutation status) (11). Clinical research on certain PARP

inhibitors is still exploring more suitable dosing regimens and

combination therapy strategies (12–15).

Numerous studies have focused on PARP and its

inhibitors as therapeutic targets (16–18).

However, in the actual clinical treatment of patients with TNBC,

the efficacy of PARP inhibitors does not always mirror the

promising results observed in experimental models, thus warranting

reflection from researchers and clinicians on the outcomes. The

main objective of the present study was to explore potential

directions for advancing the use of PARP inhibitors in TNBC

treatment by integrating feasible therapeutic strategies with the

current clinical trial performance of PARP inhibitors in TNBC. The

present review focuses on the molecular mechanisms of PARP and its

inhibitors, aiming to provide insights into optimizing the use of

these agents in future TNBC therapies.

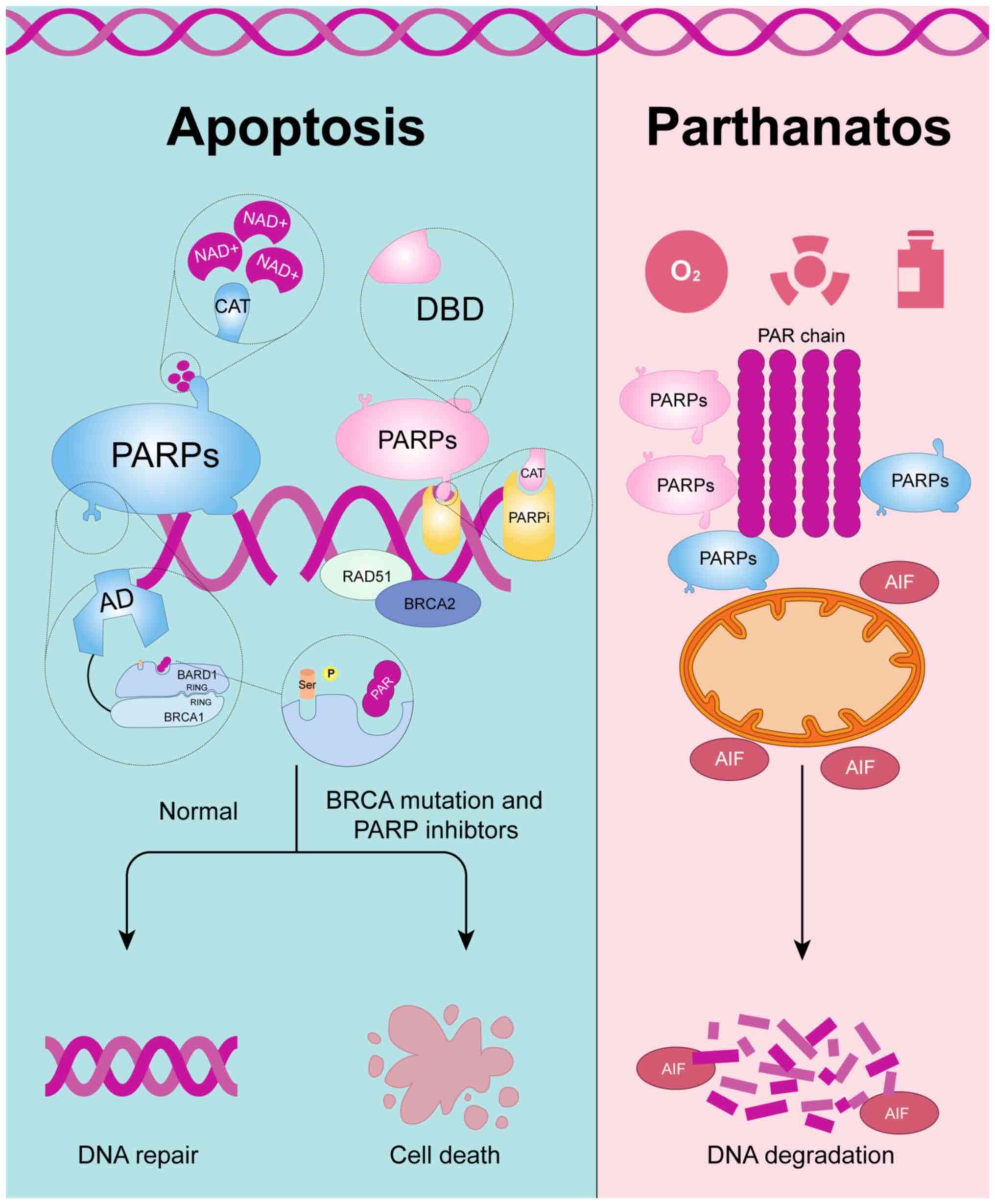

PARPs are a family of DNA repair enzymes that were

first identified in the 1960s (19). To date, 17 members of the PARP

family have been identified, with PARP-1, PARP-2 and PARP-3 being

the most extensively studied. PARP-1 is a protease characterized by

highly conserved domains, consisting of three main functional

regions: The DNA-binding domain (DBD), the auto-modification domain

(AD) and the catalytic (CAT) domain. The DBD is responsible for

recognizing and binding to damaged DNA fragments, particularly

single-strand breaks (SSBs). Once PARP-1 detects DNA damage, it

binds to the damaged site via its DBD and catalyzes the conversion

of NAD+ through its CAT, transferring ADP-ribose units from NAD+ to

PARP itself or other acceptor proteins, forming PAR chains. This

modification, known as poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation), rapidly

initiates a series of downstream signals, coordinating the protein

network involved in DNA repair (20). In this process, the AD, primarily

associated with BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) regions, plays a key role

in facilitating protein-protein interactions and regulating PARP's

dissociation from DNA after it recognizes and binds to DNA-damage

sites. During DNA repair, PARP identifies and binds to SSBs through

its zinc finger domain, which subsequently activates its CAT

domain. The CAT domain is responsible for enzymatic activity,

including the cleavage of NAD+ and the formation of PAR chains

(Fig. 1). This process alters the

spatial conformation of PARP, weakening its binding affinity to DNA

and allowing it to dissociate from the site of the DNA break

(21,22).

PARP inhibitors have shown promise for treating

patients with cancer carrying BRCA1/2 mutations, particularly

demonstrating significant clinical efficacy in ovarian and breast

cancer (23,24). Based on the strategy of targeting

homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD), PARP inhibitors

block DNA repair, leading to cancer cell death and effectively

suppressing tumor growth. However, as their clinical applications

have expanded, the issue of drug resistance has gradually emerged

(25). Overcoming resistance to

PARP inhibitors and extend their use to patients without BRCA

mutations have become key areas of current research.

Increasing evidence suggests that PARP-1 activation

can be triggered by a range of other stimuli, such as

protein-protein interactions or changes in redox states. These

findings underscore its role as a regulator involved in chromatin

remodeling and histone PARylation, or as a transcriptional

co-factor in gene expression regulation (26–28).

Furthermore, excessive activation of PARP can be

induced by various stressors, including oxidative stress, radiation

and chemotherapeutic agents, leading to an energy-depleting form of

cell death known as parthanatos, along with apoptosis-inducing

factor release and widespread DNA degradation (Fig. 1). Parthanatos has been applied in

neuroscience (29,30); however, it remains largely

unexplored in oncology. Therefore, there is considerable potential

for further investigation in this area.

In the field of DNA damage repair and breast cancer,

particularly TNBC, the key molecular players are most notably

p53 and BRCA1/2. Mutations in p53 can

influence the expression of key genes associated with cell

proliferation, including MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription

factor, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 and cyclin E2, through

direct or indirect pathways (31–33).

Although TP53 is the most frequently altered gene in breast cancer,

p53 remains in its wild-type form >2/3 of cases. However,

in basal-like breast cancer cases, most of which are triple

negative, the mutation frequency of p53 reaches 88%

(34). BRCA1 and

BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes linked to breast cancer,

playing essential roles in homologous recombination repair (HRR).

Mutations in BRCA1 are frequently observed in patients with

breast cancer, resulting in defects in DNA repair, abnormal

centrosome replication, and impaired cell cycle and spindle

checkpoint functions. This has led to the hypothesis that

BRCA1 mutations contribute to tumorigenesis through genomic

instability (35). These mutations

not only endow cells with malignant potential but also allow the

use of targeted therapies.

The concept of synthetic lethality refers to the

phenomenon where two different metabolic pathways or gene functions

compensate for one another; inhibiting either pathway alone does

not result in cell death, but simultaneous inhibition of both leads

to cell death, which also applies to tumor cells (36). Mutations in the p53 and

BRCA1/2 genes in patients disable one of the primary DNA

repair pathways, and further inhibition of the DNA repair function

of PARP leads to pronounced cell death (37). This theory has been validated in

numerous experiments. For instance, Bryant et al (38) demonstrated that BRCA2

deficiency (either BRCA2+/− or BRCA2−/−)

resulted in HRR defects, and mice with BRCA2 mutations showed a

high sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, which induced replication fork

collapse and selectively killed the defective cells, while cells

with normal BRCA function remained largely unaffected. Farmer et

al (39) elucidated the

mechanism involving the interaction between BRCA2 and RAD51,

highlighting that the rapid recruitment of RAD51 to DNA damage

sites was fundamental to the HRR pathway. While PARP1 does not play

a direct role in HRR, its absence increases the need for an

efficient HRR pathway, possibly due to the conversion of unrepaired

SSBs into double-strand breaks. Normally, BRCA2 recruits RAD51 to

these sites for HRR, but without functional BRCA2, HRR does not

occur (39).

BRCA1-associated ring domain 1 (BARD1) is a protein

that forms a heterodimer with BRCA1 and plays a crucial role in DNA

damage repair. Regarding the mechanism by which BRCA molecules are

recruited to DNA damage sites, the role of BARD1 has been widely

recognized. BARD1, the primary partner of BRCA1, contains tandem

BRCT motifs. The heterodimer of BARD1 and BRCA1 is targeted

to sites of DNA damage mainly through their ring-like structures,

while the BRCT domains, which recognize phosphorylated serine

motifs, influence the translocation of the dimer at DNA sites

(40,41). Additionally, the interaction between

BRCT and PAR occurs through the binding of each ADP-ribose unit in

PAR, thereby ensuring the adequate progression of HRR (42,43).

Protein ubiquitination not only plays a key role in

protein degradation but also has crucial functions in DNA damage

repair and maintaining genomic stability. A study has shown that

checkpoint protein with FHA and RING domains (CHFR), through its

interaction with PARP1, regulates the crosstalk between PARylation

and ubiquitination. PARP1 recruits downstream DNA repair factors

via PAR modification, while CHFR may regulate the ubiquitination of

PAR and repair proteins, thereby modulating the duration and

intensity of PARP1 activity during the DNA damage repair process

(44). This coordinated regulation

is critical to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of DNA damage

repair, and it may also confer sensitivity to PARP inhibitors in

TNBC cells (45). Furthermore, a

diverse range of ubiquitin ligases have been identified, including

deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase (DTX), ring finger protein 8(RNF8) and

mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1(MDC1) (46–49).

The combined use of drugs targeting ubiquitin ligases exacerbates

the accumulation of DNA damage, leading to unrepaired DNA breaks in

cancer cells, ultimately triggering cell death.

Epigenetic modifications refer to alterations in

gene expression that do not involve changes to the DNA sequence

itself. Common epigenetic modifications include DNA methylation and

histone modifications (such as acetylation, methylation and

phosphorylation), which regulate gene expression by altering

chromatin structure (50). One of

the central mechanisms of epigenetic regulation involves modifying

chromatin conformation to control gene accessibility. PARP-1 and

other members of the PARP family modulate chromatin plasticity

through the PARylation of histones (51,52).

For example, previous research has shown that histones such as H2A

at K13, H2B at K30, H3 at K27 and K37, and H4 at K16 can serve as

ADP-ribose acceptor sites (53).

The PARylation of H2 introduces a considerable negative charge

around chromatin proteins, leading to chromatin decondensation,

thereby facilitating the access of DNA repair factors to sites of

damage (54). Zhou et al

(55) treated trophoblast stem

cells with a DNA-modifying agent in PAR glycohydrolase-deficient

cells and found that excessive PARylation of histones, due to

inhibition of PAR chain hydrolysis, increased the sensitivity of

the cells to DNA damage-induced cell death.

Activation of PARP-1 can also alter chromatin

structure by recruiting chromatin remodeling complexes such as the

Switch/sucrose non-fermentable complex, which plays a critical role

in regulating chromatin structure and gene expression by altering

chromatin accessibility (56).

However, in tumor cells, this can more easily induce synthetic

lethality (57). It is worth noting

that PARylation can activate gene expression but can also regulate

gene silencing through chromatin compaction. For instance, SIRT1, a

deacetylase that promotes cell survival, competes with PARP-1 as

both rely on NAD+ as a substrate. Overactivation of PARP-1 can

reduce SIRT1 activity, thereby contributing to gene silencing

(58). Previous research has

suggested that certain viruses can exploit PARP-1 to modify viral

episomes or host genes, aiding long-term viral infections of DNA

viruses, which can lead to tumorigenesis (59).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are also involved in

the epigenetic regulation of gene expression by interacting with

epigenetic regulatory protein complexes, such as histone-modifying

enzymes and DNA methyltransferases, and are closely associated with

apoptosis, autophagy and transformation. Increasing evidence has

revealed their role in promoting tumor initiation, invasion and

malignancy (60–62). A PAR-related study has reported that

a human lncRNA-encoded micropeptide called PACMP not only inhibits

the ubiquitination of C-terminal binding protein-interacting

protein by blocking its interaction with KLHL15 but also

directly binds to DNA damage-induced PAR chains, thus enhancing

PARP1-dependent PARylation. Targeting lnc15.2/PACMP has shown

reversal of resistance to several chemotherapy drugs, including

PARP inhibitors, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related inhibitors

and cyclin-dependent kinase-4/6 inhibitors (63). However, there is limited research on

targeted therapy of lncRNAs related to breast cancer in combination

with PARP inhibitors, thus offering a broad scope for exploration

in the future.

Both the inhibition and activation of PARP can

induce cell death, with the former primarily attributed to

apoptosis caused by DNA damage within a controllable range for the

cell, while the latter triggers energy depletion and widespread

degradation of genetic material by exhausting the precursors of

PAR, such as NAD+ and ATP (64).

For TNBC, the mainstream treatment still focuses on

PARP inhibitors, mainly in combination with other clinical

chemotherapy agents. For example, combining PARP inhibitors with

DNA cross-linking agents such as carboplatin and cisplatin

exacerbates DNA damage, while combining them with microtubule

inhibitors such as paclitaxel increases replication stress in tumor

cells. Additionally, targeting signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt

inhibition or anti-angiogenesis agents can further prevent tumor

growth and metastasis (Fig. 2)

(65).

There is a close association between immunotherapy

and PARP inhibitors. From a metabolomics perspective, Ding et

al (66) reported that

guanosine diphosphate-mannose (GDP-M), a metabolite, accumulates in

cells and reduces the interaction between BRCA2 and

ubiquitin-specific peptidase 21. This promotes the

ubiquitin-mediated degradation of BRCA2, thereby inhibiting HRR.

Furthermore, the authors found that the combination of GDP-M and

DNA-damaging agents activates STING-dependent antitumor immunity in

immunocompetent mouse models. Using whole-genome clustered

regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats screening, Zhong

et al (67) identified PARP1

as a restriction factor for herpes simplex virus 1 replication. By

combining their custom-designed oncolytic virus with a PARP

inhibitor, the authors were able to render TNBC highly sensitive to

immune checkpoint inhibitors. Seaweed polysaccharides have been

recommended as anticancer supplements and for boosting human

health. Chen et al (68)

observed that oligo-fucoidan combined with Olaparib more

effectively inhibited the formation of TNBC stem cell mammospheres,

while also suppressing the oncogenic IL-6/phosphorylated EGFR/PD-L1

pathway. This combination promoted the repolarization of M2

macrophages into M0-like and M1-like macrophages, thereby inducing

immune activation. In the same study, this effect has been

confirmed in mice, where oral administration of oligo-fucoidan

alongside Olaparib inhibited postoperative TNBC recurrence and

metastasis (68).

Before evaluating the clinical efficacy of PARP

inhibitors, it is essential to understand their mechanisms of

action. The catalytic function of PARP enzymes stems from the CAT

domain, which includes a binding site for NAD+. PARP inhibitors

competitively bind to the catalytic active site of PARP, thereby

blocking the entry of NAD+. Simultaneously, when PARP inhibitors

bind to the catalytic site, PARP is unable to complete PARylation

and dissociates from DNA damage sites. This trapping effect

prevents other DNA repair factors from reaching the damage site,

further exacerbating DNA damage. Therefore, the efficacy of a PARP

inhibitor largely depends on its binding strength to the CAT domain

and its ability to trap PARP at DNA damage sites (22,69).

Over the past two decades, numerous PARP inhibitors

have entered clinical trials. These drugs include Iniparib

(NCT01173497) (70) and Veliparib

(NCT02163694) (71) Olaparib

(NCT02734004) (72), Rucaparib

(NCT02042378) (73), Niraparib

(NCT05734911) (74), Talazoparib

(NCT04987931) (75), Fuzuloparib

(NCT05753826, Recruiting) and Pamiparib (NCT03333915) (76). Understanding their efficacy in these

trials provides valuable insights for developing effective clinical

treatment strategies for patients in the future.

Iniparib (chemical name: BSI-201) was initially

considered one of the promising candidate drugs in the category of

PARP inhibitors. In 2011, it entered phase II clinical trials and

demonstrated significant efficacy in treating TNBC (clinical trial

no. NCT00540358) (77). However,

subsequent phase III randomized controlled trials (clinical trial

no. NCT00938652) (78) delivered

disappointing results. In the trial, 261 patients treated with the

combination of gemcitabine + carboplatin + Iniparib were compared

with 258 patients receiving gemcitabine + carboplatin alone, and no

statistically significant difference was observed in overall

survival (OS) [hazard ratio (HR)=0.88; 95% confidence interval

(CI), 0.69–1.12; P=0.28] or progression-free survival (PFS)

(HR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.65–0.98; P=0.027). These results indicated that

the potential benefits of Iniparib required further evaluation

(78).

Olaparib (chemical name: AZD2281), developed by

AstraZeneca, is the first widely used PARP inhibitor in clinical

settings. Its earliest clinical trials began in 2005, focusing on

breast and ovarian cancer cases with BRCA1/2 mutations, and it also

showed efficacy in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (81). In 2009, the results of a phase I

clinical trial (clinical trial no. NCT00516373) demonstrated the

effectiveness of Olaparib in BRCA-mutated ovarian and breast cancer

(23). Subsequently, a phase II,

multicenter, open-label, non-randomized study (clinical trial no.

NCT00679783) was conducted to evaluate Olaparib treatment in women

with ovarian cancer and TNBC. The results showed that 18 out of 64

patients with ovarian cancer had a confirmed objective response,

while no responses were observed in any of the 26 patients with

TNBC (15). Similarly, a

multicenter phase II clinical study in 2015 reported the

therapeutic response in germline BRCA1/2-mutated tumors, with a

relatively low response rate of 12.9% (8/62; 95% CI, 5.7–23.9) in

breast cancer. Additionally, 47% of the patients experienced stable

disease for >8 weeks (95% CI, 34.0–59.9) (82).

Whether used as a monotherapy or in combination with

other drugs, the majority of the early clinical studies reported

that ≥50% of patients experienced grade ≥3 adverse events (82–86).

Previous studies have also evaluated the safety and tolerability of

combining Olaparib with radiotherapy. For instance, Loap et

al (87–89) conducted the long-term RADIOPARP

phase I trial in 24 patients with TNBC who exhibited residual

disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These patients were treated

with four different doses of Olaparib (50, 100, 150 and 200 mg,

twice daily). Initially, no dose-limiting toxicities were observed,

and after 1 year of follow-up, no treatment-related grade ≥3

toxicities were noted. Additionally, the 3-year OS and event-free

survival rates were 83% (95% CI, 70–100%) and 65% (95% CI, 48–88%),

respectively.

In recent years, the majority of clinical trials

involving Olaparib have progressed to phase II or III (Table I). Based on the trial endpoints, it

can be observed that Olaparib has improved pathological complete

response and OS in patients, although the improvements are not

always statistically significant. Additionally, certain studies

have not only focused on efficacy but also on quality of life

(QoL). For example, a patient-reported outcomes study indicated

that patients receiving Olaparib experienced statistically

significantly higher levels of fatigue at 6 and 12 months during

the treatment and follow-up periods compared to those receiving

placebo. However, this did not reach the predetermined clinical

significance threshold of a 3-point difference. At 18 and 24

months, the Olaparib and placebo scores were similar (90). In conclusion, the importance of

these clinical studies lies in helping physicians make more precise

decisions about treatment options by considering both QoL and

efficacy, ensuring that therapeutic effectiveness is maximized

while minimizing the burden on the QoL of patients.

The earliest clinical study on Rucaparib (chemical

name: AG-014699) was reported in 2008, when Plummer et al

(91) evaluated the safety,

efficacy, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of AG-014699 in

combination with temozolomide in adult patients with advanced

malignant tumors. The study observed encouraging evidence of

activity. In 2016, clinical research focusing on breast

cancer-related treatments indicated that Rucaparib was well

tolerated at doses ≤480 mg/day and was a potent PARP inhibitor,

providing sustained inhibition for ≥24 h after a single dose,

although specific efficacy data for patients with breast cancer

were not provided (92).

Another phase II clinical trial in patients with

TNBC found that Rucaparib significantly reduced circulating tumor

DNA levels in homologous recombination repair-deficient cancer and

induced the expression of interferon response genes, suggesting

that Rucaparib may enhance antitumor effects not only through

inhibition of DNA repair pathways but also by triggering DNA

damage-induced immune responses (93). In another study, Kristeleit et

al (94) evaluated the

combination of Rucaparib with the immune checkpoint inhibitor

Atezolizumab in advanced gynecological cancer or TNBC. Patients

with higher PD-L1 levels and BRCA mutations prior to treatment were

more likely to experience adverse reactions such as

gastrointestinal symptoms, elevated levels of liver enzymes or

anemia. Markers of DNA damage repair (such as RAD51 foci)

and apoptosis markers were also reduced. This suggests that there

may be a synergistic effect between the immune response and PARP

inhibitors. Rucaparib may enhance tumor antigen production by

promoting DNA damage, thereby activating the immune system.

Niraparib (chemical name: MK-4827) is an oral,

potent and selective inhibitor of PARP-1 and PARP-2, capable of

inducing functional loss in BRCA and phosphatase and tensin

homolog. In 2013, Sandhu et al (95) clinically evaluated its safety and

tolerability, establishing 300 mg/day as the maximum tolerated

dose. The oral bioavailability of Niraparib in humans was measured

at 72.7% (96). In the

multi-country, phase III Niraparib in Patients with

Platinum-Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer trial (NCT01847274)

conducted in adult patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent

ovarian cancer (97), Niraparib

significantly prolonged the median PFS, regardless of the presence

of germline BRCA mutations or HRD, highlighting its distinct

advantage (98).

Although clinical research on the treatment of TNBC

with Niraparib remains limited, a combination therapy study

involving Niraparib (MK-4827) and fractionated radiotherapy in the

MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line has demonstrated promising results.

Regardless of p53 status, MK-4827 reduced tumor PAR levels within 1

h of administration, with the effect lasting ≤24 h (99). These findings provide a foundation

for future research in this area.

Talazoparib (chemical name: BMN673), developed by

BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., is a second-generation PARP

inhibitor. Previous research has shown that BMN673 exhibits

selective cytotoxicity against tumor cells and induces DNA repair

biomarkers at notably lower concentrations compared to

first-generation PARP1/2 inhibitors such as Olaparib, Rucaparib and

Veliparib (PARP1 half-maximal inhibitory concentration, 0.57

nmol/l) (100). In a 2017 phase I

clinical trial (clinical trial no. NCT01286987), Talazoparib

demonstrated notable antitumor activity and safety as a

monotherapy, with 7 out of 14 patients with BRCA-mutated breast

cancer showing confirmed responses, resulting in a response rate of

50%. Grade 3–4 adverse events included anemia (17 out of 71

patients; 24%) and thrombocytopenia (13 out of 71 patients; 18%)

(12).

Talazoparib has been widely applied in clinical

treatments for breast cancer, primarily as a monotherapy to assess

efficacy (Table II). For instance,

a phase II single-arm, open-label study (clinical trial no.

NCT03499353) evaluated the efficacy of Talazoparib as a neoadjuvant

therapy in patients with TNBC, and achieved a pathological complete

response rate of 45.8% (95% CI, 29.4–63.2%) in the evaluable

population, demonstrating considerable activity (101).

It is important to note that, when combining

Talazoparib with other potent anticancer drugs, careful attention

must be paid to dosing and administration sequence. Previous

research has indicated a potential synergistic effect between

antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and PARP inhibitors. ADCs can

effectively increase DNA damage in tumor cells, and subsequent use

of PARP inhibitors can further block DNA repair, leading to cancer

cell apoptosis (102). However,

simultaneous administration in clinical settings has shown

significant toxicity, particularly myelosuppression. Sequential

administration, however, creates a time window that allows PARP

inhibitors to act more effectively within tumor cells without

increasing toxicity (13).

Veliparib, a PARP inhibitor, has been evaluated in

combination with other drugs in clinical trials for various cancer

types. In the treatment of TNBC, its combination with cisplatin or

carboplatin has shown good tolerability and response rates

(14). In addition to its use in

classic gynecological tumors such as breast and ovarian cancer,

Veliparib has also been investigated in the treatment of non-small

cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer and acute

myeloid leukemia (103–106). Although Veliparib has not yet

received broad clinical approval, its extensive research and

application in various cancer types provides promising insights for

future therapeutic strategies.

Recently developed in China, Fuzuloparib and

Pamiparib are novel PARP inhibitors. In a phase I clinical trial

(clinical trial no. NCT03945604) of Fuzuloparib for patients with

recurrent or metastatic TNBC, 29 patients received camrelizumab

(200 mg, every 2 weeks), Apatinib (375 or 500 mg, daily) and

Fuzuloparib (starting dose of 100 mg, twice daily). In total, 2

patients (6.9%; 95% CI, 0.9–22.8) had an objective response, while

the disease control rate was 62.1% (95% CI, 42.3–79.3). The median

PFS was 5.2 months (95% CI, 3.6–7.3), while the 12-month OS rate

was 64.2% (95% CI, 19.0–88.8), indicating controllable safety and

preliminary antitumor activity (107). Similarly, another phase I trial

(clinical trial no. NCT03075462) confirmed the acceptable safety of

Fuzuloparib combined with Apatinib in patients with advanced

ovarian cancer or TNBC (108).

In addition, Pamiparib in combination with the

immune checkpoint inhibitor Tislelizumab demonstrated efficacy in a

dose-escalation study for treating various advanced solid tumors

(109). In monotherapy for

patients with non-mucinous high-grade ovarian cancer and TNBC in

China, the most common adverse effects were fatigue, nausea and

hemoglobin reduction. Among all patients with TNBC who were

evaluable under the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

criteria (n=5), disease progression was reported, indicating the

need for further evidence to support its efficacy in breast cancer

(76).

Although PARP inhibitors have shown significant

efficacy in cancer cases with BRCA mutations, resistance remains

one of the most challenging clinical issues. Resistance can arise

through various mechanisms, and previous studies have uncovered

some key pathways. For example, certain resistant cancer cells can

overcome the effects of PARP inhibitors by reversing BRCA gene

mutations or restoring BRCA1/2 function (11,110).

Additionally, PARP inhibitors act not only by inhibiting PARP

activity but also by inducing PARP trapping, which increases DNA

damage. Resistant cancer cells can reduce PARP trapping by altering

the expression or function of PARP-related proteins, thereby

diminishing the efficacy of PARP inhibitors (111). Moreover, cancer cells may repair

DNA through alternative pathways, using different enzymes or repair

mechanisms. For instance, tankyrase, which has a catalytic activity

similar to PARP, regulates other proteins through ADP-ribosylation.

This suggests that tankyrase may serve as an alternative mechanism

during PARP inhibitor therapy, and several studies have summarized

its importance in cancer treatment (112–114). It is also noteworthy that

upregulation of the ABCB1 gene, which encodes the

P-glycoprotein efflux pump, may contribute to drug efflux and

resistance to PARP inhibitors (115).

As a result, numerous studies have evaluated the

efficacy of PARP inhibitors in tumors without BRCA mutations,

expanding their potential application beyond BRCA-mutated tumors.

HRD testing tools have been developed to assess genomic instability

(for example, copy number alterations, gene rearrangements and

microsatellite instability) in tumors. This enables the

identification of HRD-positive patients who are more likely to

benefit from PARP therapy (116).

Gasdermin-C (GSDMC) is a member of the gasdermin family protein,

which contains a gasdermin domain, and GSDMC/caspase-8 are key

molecules in pyroptosis. Wang et al (117) found that treatment with PARP

inhibitors triggered GSDMC/caspase-8-mediated pyroptosis in cancer

cells. Additionally, GSDMC-mediated pyroptosis increased the

population of memory CD8+ T cells in the lymph nodes,

spleen and tumors, thereby promoting the infiltration of cytotoxic

CD8+ T cells into the tumor microenvironment. Notably,

this process was independent of BRCA mutations.

Furthermore, the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in

non-BRCA-mutated tumors has being explored. For instance, a phase

II trial evaluating Olaparib in patients with advanced TNBC or

high-grade serous and/or undifferentiated ovarian cancer without

BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations found that, among 63 patients with ovarian

cancer, the objective response rate was 41% in the mutation group

(n=17) and 24% in the non-mutation group (n=46). No responses were

reported in any of the 26 patients with breast cancer (15). Another similar study also explored

the use of PARP inhibitors in patients with BRCA wild-type TNBC

(118).

Replication fork stability can endow BRCA-deficient

cells with resistance. A defect in PTIP, a paired box transcription

activation domain interaction protein, does not restore homologous

recombination but inhibits the recruitment of the MRE11 nuclease to

stalled replication forks. This, in turn, protects nascent DNA

strands from extensive degradation (119). Tan and Xu (120) found that ubiquitin-fold modifier

modification (UFMylation) played a critical role in replication

fork dynamics in BRCA1-deficient cells, where PTIP UFMylation

promoted the resection of nascent DNA, conferring resistance to

BRCA1-deficient cells. Furthermore, Tian et al (121) demonstrated that, during

replication stress, UFL1, a UFM1-specific E3 ligase,

localized to stalled forks and catalyzed PTIP UFMylation, thus

providing a mechanism for UFMylation in PTIP regulation. These

studies offer potential avenues for overcoming resistance to PARP

inhibitors in patients with BRCA-deficient TNBC.

In conclusion, identifying more precise molecular

biomarkers, optimizing drug sequencing and dosing in resistant

patients, and improving the use of PARP-related cell death

mechanisms (such as energy depletion) are potential strategies for

the future treatment of breast cancer, particularly TNBC.

The present review focuses on the role of PARP

inhibitors in the treatment of TNBC, particularly highlighting

their efficacy in BRCA mutation-associated tumors. By analyzing key

mechanisms of DNA damage repair, it was observed that, in multiple

clinical trials, PARP inhibitors have demonstrated not only strong

efficacy in BRCA-mutated TNBC but also potential in

non-BRCA-mutated tumors. Despite the notable efficacy of PARP

inhibitors in patients with BRCA-mutated TNBC, the emergence of

resistance remains a major challenge in clinical applications, and

identifying additional biomarkers to combat this resistance

requires further exploration.

Future research should focus on overcoming

resistance to PARP inhibitors through combination therapy

strategies while refining patient selection by integrating genomic

data and biomarker analysis. This should help ensure optimal

efficacy with the most appropriate dosing for the suitable

patients. Additionally, further investigation of combination

treatment regimens and sequencing should provide improved survival

benefits to patients.

The authors would like to thank Ms. Sihan Lin (First

Clinical College, Wuhan University, China) for providing important

contributions to Figure 2 during

the revision of the manuscript.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

YH and LW contributed to the study conception and

design. YH proposed the concept of the study and drafted for the

article, and performed literature search and data analysis. LW

determined the writing framework of the article, put forward

valuable revision suggestions for the first draft and also provided

assistance in the detailed revisions of the article. Both authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Newman LA, Freedman

RA, Smith RA, Star J, Jemal A and Siegel RL: Breast cancer

statistics 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:477–495. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wu SY, Wang H, Shao ZM and Jiang YZ:

Triple-negative breast cancer: New treatment strategies in the era

of precision medicine. Sci China Life Sci. 64:372–388. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yuan P, Ma N and Xu B: Poly (adenosine

diphosphate-ribose) polymerase inhibitors in the treatment of

triple-negative breast cancer with homologous repair deficiency.

Med Res Rev. 44:2774–2792. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Konstantinopoulos PA, Ceccaldi R, Shapiro

GI and D'Andrea AD: Homologous recombination deficiency: Exploiting

the fundamental vulnerability of ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov.

5:1137–1154. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F,

Shore N, Sandhu S, Chi KN, Sartor O, Agarwal N, Olmos D, et al:

Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N

Engl J Med. 382:2091–2102. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mateo J, Porta N, Bianchini D, McGovern U,

Elliott T, Jones R, Syndikus I, Ralph C, Jain S, Varughese M, et

al: Olaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant

prostate cancer with DNA repair gene aberrations (TOPARP-B): A

multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

21:162–174. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Markham A: Pamiparib: First Approval.

Drugs. 81:1343–1348. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee A: Fuzuloparib: First Approval. Drugs.

81:1221–1226. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xiao F, Wang Z, Qiao L, Zhang X, Wu N,

Wang J and Yu X: Application of PARP inhibitors combined with

immune checkpoint inhibitors in ovarian cancer. J Transl Med.

22:7782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li Q, Qian W, Zhang Y, Hu L, Chen S and

Xia Y: A new wave of innovations within the DNA damage response.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Afghahi A, Timms KM, Vinayak S, Jensen KC,

Kurian AW, Carlson RW, Chang PJ, Schackmann E, Hartman AR, Ford JM

and Telli ML: Tumor BRCA1 reversion mutation arising during

neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in triple-negative breast

cancer is associated with therapy resistance. Clin Cancer Res.

23:3365–3370. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

de Bono J, Ramanathan RK, Mina L, Chugh R,

Glaspy J, Rafii S, Kaye S, Sachdev J, Heymach J, Smith DC, et al:

Phase I, dose-escalation, two-part trial of the PARP inhibitor

talazoparib in patients with advanced germline BRCA1/2 mutations

and selected sporadic cancers. Cancer Discov. 7:620–629. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bardia A, Sun S, Thimmiah N, Coates JT, Wu

B, Abelman RO, Spring L, Moy B, Ryan P, Melkonyan MN, et al:

Antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan enables a sequential

TOP1/PARP inhibitor therapy strategy in patients with breast

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 30:2917–2924. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rodler ET, Kurland BF, Griffin M, Gralow

JR, Porter P, Yeh RF, Gadi VK, Guenthoer J, Beumer JH, Korde L, et

al: Phase I study of veliparib (ABT-888) combined with cisplatin

and vinorelbine in advanced triple-negative breast cancer and/or

BRCA mutation-associated breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

22:2855–2864. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gelmon KA, Tischkowitz M, Mackay H,

Swenerton K, Robidoux A, Tonkin K, Hirte H, Huntsman D, Clemons M,

Gilks B, et al: Olaparib in patients with recurrent high-grade

serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or

triple-negative breast cancer: A phase 2, multicentre, open-label,

non-randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 12:852–861. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhu S, Wu Y, Song B, Yi M, Yan Y, Mei Q

and Wu K: Recent advances in targeted strategies for

triple-negative breast cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 16:1002023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Subhan MA, Parveen F, Shah H, Yalamarty

SSK, Ataide JA and Torchilin VP: Recent advances with precision

medicine treatment for breast cancer including triple-negative

sub-type. Cancers (Basel). 15:22042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Won KA and Spruck C: Triple-negative

breast cancer therapy: Current and future perspectives (Review).

Int J Oncol. 57:1245–1261. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kraus WL: PARPs and ADP-ribosylation: 50

Years … and counting. Mol Cell. 58:902–910. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Schreiber V, Dantzer F, Ame JC and de

Murcia G: Poly(ADP-ribose): Novel functions for an old molecule.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 7:517–528. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Duma L and Ahel I: The function and

regulation of ADP-ribosylation in the DNA damage response. Biochem

Soc Trans. 51:995–1008. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rouleau-Turcotte É and Pascal JM:

ADP-ribose contributions to genome stability and PARP enzyme

trapping on sites of DNA damage; paradigm shifts for a

coming-of-age modification. J Biol Chem. 299:1053972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P,

Mergui-Roelvink M, Mortimer P, Swaisland H, Lau A, O'Connor MJ, et

al: Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA

mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 361:123–134. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM,

Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, Friedlander M, Arun B, Loman N, Schmutzler

RK, et al: Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in

patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer:

A proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 376:235–244. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kim D and Nam HJ; PARP inhibitors, :

Clinical limitations and recent attempts to overcome them. Int J

Mol Sci. 23:84122022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim MY, Mauro S, Gévry N, Lis JT and Kraus

WL: NAD+-dependent modulation of chromatin structure and

transcription by nucleosome binding properties of PARP-1. Cell.

119:803–814. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kun E, Kirsten E, Mendeleyev J and Ordahl

CP: Regulation of the enzymatic catalysis of poly(ADP-ribose)

polymerase by dsDNA, polyamines, Mg2+, Ca2+, histones H1 and H3,

and ATP. Biochemistry. 43:210–216. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kraus WL: Transcriptional control by

PARP-1: Chromatin modulation, enhancer-binding, coregulation, and

insulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 20:294–302. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Baek SH, Bae ON, Kim EK and Yu SW:

Induction of mitochondrial dysfunction by poly(ADP-ribose) polymer:

Implication for neuronal cell death. Mol Cells. 36:258–266. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tuo QZ, Zhang ST and Lei P: Mechanisms of

neuronal cell death in ischemic stroke and their therapeutic

implications. Med Res Rev. 42:259–305. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang Z, Li Y, Yang J, Sun Y, He Y, Wang Y,

Liang Y, Chen X, Chen T, Han D, et al: CircCFL1 promotes TNBC

stemness and immunoescape via deacetylation-mediated c-Myc

deubiquitylation to facilitate mutant TP53 transcription. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 11:e24046282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

De Souza C, Madden JA, Minn D, Kumar VE,

Montoya DJ, Nambiar R, Zhu Z, Xiao WW, Tahmassebi N, Kathi H, et

al: The P72R polymorphism in R248Q/W p53 mutants modifies the

mutant effect on epithelial to mesenchymal transition phenotype and

cell invasion via CXCL1 expression. Int J Mol Sci. 21:80252020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Macdonald FH, Yao D, Quinn JA and

Greenhalgh DA: PTEN ablation in Ras(Ha)/Fos skin carcinogenesis

invokes p53-dependent p21 to delay conversion while p53-independent

p21 limits progression via cyclin D1/E2 inhibition. Oncogene.

33:4132–4143. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Marvalim C, Datta A and Lee SC: Role of

p53 in breast cancer progression: An insight into p53 targeted

therapy. Theranostics. 13:1421–1442. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Deng CX: Tumorigenesis as a consequence of

genetic instability in Brca1 mutant mice. Mutat Res. 477:183–189.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Du Y, Luo L, Xu X, Yang X, Yang X, Xiong

S, Yu J, Liang T and Guo L: Unleashing the power of synthetic

lethality: Augmenting treatment efficacy through synergistic

integration with chemotherapy drugs. Pharmaceutics. 15:24332023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Anders CK, Winer EP, Ford JM, Dent R,

Silver DP, Sledge GW and Carey LA: Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase

inhibition: ‘Targeted’ therapy for triple-negative breast cancer.

Clin Cancer Res. 16:4702–4710. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker

KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ and Helleday T:

Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 434:913–917. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN,

Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I,

Knights C, et al: Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant

cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 434:917–921. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tarsounas M and Sung P: The

antitumorigenic roles of BRCA1-BARD1 in DNA repair and replication.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:284–299. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Peña-Guerrero J, Fernández-Rubio C,

García-Sosa AT and Nguewa PA: BRCT domains: Structure, functions,

and implications in disease-new therapeutic targets for innovative

drug discovery against infections. Pharmaceutics. 15:18392023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li M and Yu X: Function of BRCA1 in the

DNA damage response is mediated by ADP-ribosylation. Cancer Cell.

23:693–704. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Becker JR, Clifford G, Bonnet C, Groth A,

Wilson MD and Chapman JR: BARD1 reads H2A lysine 15 ubiquitination

to direct homologous recombination. Nature. 596:433–437. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liu C, Wu J, Paudyal SC, You Z and Yu X:

CHFR is important for the first wave of ubiquitination at DNA

damage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:1698–1710. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wu W, Zhao J, Xiao J, Wu W, Xie L, Xie X,

Yang C, Yin D and Hu K: CHFR-mediated degradation of RNF126 confers

sensitivity to PARP inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer

cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 573:62–68. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Djerir B, Marois I, Dubois JC, Findlay S,

Morin T, Senoussi I, Cappadocia L, Orthwein A and Maréchal A: An E3

ubiquitin ligase localization screen uncovers DTX2 as a novel

ADP-ribosylation-dependent regulator of DNA double-strand break

repair. J Biol Chem. 300:1075452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yan Q, Xu R, Zhu L, Cheng X, Wang Z, Manis

J and Shipp MA: BAL1 and its partner E3 ligase, BBAP, link

Poly(ADP-ribose) activation, ubiquitylation, and double-strand DNA

repair independent of ATM, MDC1, and RNF8. Mol Cell Biol.

33:845–857. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Kolas NK, Chapman JR, Nakada S, Ylanko J,

Chahwan R, Sweeney FD, Panier S, Mendez M, Wildenhain J, Thomson

TM, et al: Orchestration of the DNA-damage response by the RNF8

ubiquitin ligase. Science. 318:1637–1640. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Marteijn JA, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N,

Lans H, Schwertman P, Gourdin AM, Dantuma NP, Lukas J and Vermeulen

W: Nucleotide excision repair-induced H2A ubiquitination is

dependent on MDC1 and RNF8 and reveals a universal DNA damage

response. J Cell Biol. 186:835–847. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Tian H, Luan P, Liu Y and Li G:

Tet-mediated DNA methylation dynamics affect chromosome

organization. Nucleic Acids Res. 52:3654–3666. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Messner S and Hottiger MO: Histone

ADP-ribosylation in DNA repair, replication and transcription.

Trends Cell Biol. 21:534–542. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hottiger MO: ADP-ribosylation of histones

by ARTD1: An additional module of the histone code? FEBS Lett.

585:1595–1599. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Messner S, Altmeyer M, Zhao H, Pozivil A,

Roschitzki B, Gehrig P, Rutishauser D, Huang D, Caflisch A and

Hottiger MO: PARP1 ADP-ribosylates lysine residues of the core

histone tails. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:6350–6362. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, Kaufmann

SH and Poirier GG: PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat Rev

Cancer. 10:293–301. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhou Y, Feng X and Koh DW: Enhanced DNA

accessibility and increased DNA damage induced by the absence of

poly(ADP-ribose) hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 49:7360–7366. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Martin BJE, Ablondi EF, Goglia C, Mimoso

CA, Espinel-Cabrera PR and Adelman K: Global identification of

SWI/SNF targets reveals compensation by EP400. Cell.

186:5290–5307.e26. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wanior M, Krämer A, Knapp S and Joerger

AC: Exploiting vulnerabilities of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling

complexes for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 40:3637–3654. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Kolthur-Seetharam U, Dantzer F, McBurney

MW, de Murcia G and Sassone-Corsi P: Control of AIF-mediated cell

death by the functional interplay of SIRT1 and PARP-1 in response

to DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 5:873–877. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sobotka AA and Tempera I: PARP1 as an

epigenetic modulator: Implications for the regulation of host-viral

dynamics. Pathogens. 13:1312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ahmad M, Weiswald LB, Poulain L, Denoyelle

C and Meryet-Figuiere M: Involvement of lncRNAs in cancer cells

migration, invasion and metastasis: Cytoskeleton and ECM crosstalk.

J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42:1732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Bartonicek N, Maag JL and Dinger ME: Long

noncoding RNAs in cancer: Mechanisms of action and technological

advancements. Mol Cancer. 15:432016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Jiang J, Lu Y, Zhang F, Huang J, Ren XL

and Zhang R: The emerging roles of long noncoding RNAs as hallmarks

of lung cancer. Front Oncol. 11:7615822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang C, Zhou B, Gu F, Liu H, Wu H, Yao F,

Zheng H, Fu H, Chong W, Cai S, et al: Micropeptide PACMP inhibition

elicits synthetic lethal effects by decreasing CtIP and

poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Mol Cell. 82:1297–1312.e8. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Siegel C and McCullough LD: NAD+ depletion

or PAR polymer formation: Which plays the role of executioner in

ischaemic cell death? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 203:225–234. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

De P, Sun Y, Carlson JH, Friedman LS,

Leyland-Jones BR and Dey N: Doubling down on the PI3K-AKT-mTOR

pathway enhances the antitumor efficacy of PARP inhibitor in triple

negative breast cancer model beyond BRCA-ness. Neoplasia. 16:43–72.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ding JH, Xiao Y, Yang F, Song XQ, Xu Y,

Ding XH, Ding R, Shao ZM, Di GH and Jiang YZ: Guanosine

diphosphate-mannose suppresses homologous recombination repair and

potentiates antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer.

Sci Transl Med. 16:eadg77402024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zhong Y, Le H, Zhang X, Dai Y, Guo F, Ran

X, Hu G, Xie Q, Wang D and Cai Y: Identification of restrictive

molecules involved in oncolytic virotherapy using genome-wide

CRISPR screening. J Hematol Oncol. 17:362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Chen LM, Yang PP, Al Haq AT, Hwang PA, Lai

YC, Weng YS, Chen MA and Hsu HL: Oligo-Fucoidan supplementation

enhances the effect of Olaparib on preventing metastasis and

recurrence of triple-negative breast cancer in mice. J Biomed Sci.

29:702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Rudolph J, Jung K and Luger K: Inhibitors

of PARP: Number crunching and structure gazing. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 119:e21219791192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Anders C, Deal AM, Abramson V, Liu MC,

Storniolo AM, Carpenter JT, Puhalla S, Nanda R, Melhem-Bertrandt A,

Lin NU, et al: TBCRC 018: phase II study of iniparib in combination

with irinotecan to treat progressive triple negative breast cancer

brain metastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 146:557–566. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Diéras V, Han HS, Kaufman B, Wildiers H,

Friedlander M, Ayoub JP, Puhalla SL, Bondarenko I, Campone M,

Jakobsen EH, et al: Veliparib with carboplatin and paclitaxel in

BRCA-mutated advanced breast cancer (BROCADE3): A randomised,

double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

21:1269–1282. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Domchek SM, Postel-Vinay S, Im SA, Park

YH, Delord JP, Italiano A, Alexandre J, You B, Bastian S, Krebs MG,

et al: Olaparib and durvalumab in patients with germline

BRCA-mutated metastatic breast cancer (MEDIOLA): An open-label,

multicentre, phase 1/2, basket study. Lancet Oncol. 21:1155–1164.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Shroff RT, Hendifar A, McWilliams RR, Geva

R, Epelbaum R, Rolfe L, Goble S, Lin KK, Biankin AV, Giordano H, et

al: Rucaparib monotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer and a

known deleterious BRCA mutation. JCO Precis Oncol.

2018.PO.17.00316. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Zhao M, Qiu S, Wu X, Miao P, Jiang Z, Zhu

T, Xu X, Zhu Y, Zhang B, Yuan D, et al: Efficacy and safety of

niraparib as first-line maintenance treatment for patients with

advanced ovarian cancer: Real-world data from a multicenter study

in China. Target Oncol. 18:869–883. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Savill KMZ, Ivanova J, Asgarisabet P,

Falkenstein A, Balanean A, Niyazov A, Ryan JC, Kish J, Gajra A and

Mahtani RL: Characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of real-world

talazoparib-treated patients with germline BRCA-mutated advanced

HER2-negative breast cancer. Oncologist. 28:414–424. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Xu B, Yin Y, Dong M, Song Y, Li W, Huang

X, Wang T, He J, Mu X, Li L, et al: Pamiparib dose escalation in

Chinese patients with non-mucinous high-grade ovarian cancer or

advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Med. 10:109–118.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

O'Shaughnessy J, Osborne C, Pippen JE,

Yoffe M, Patt D, Rocha C, Koo IC, Sherman BM and Bradley C:

Iniparib plus chemotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast

cancer. N Engl J Med. 364:205–214. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

O'Shaughnessy J, Schwartzberg L, Danso MA,

Miller KD, Rugo HS, Neubauer M, Robert N, Hellerstedt B, Saleh M,

Richards P, et al: Phase III study of iniparib plus gemcitabine and

carboplatin versus gemcitabine and carboplatin in patients with

metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol.

32:3840–3847. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Mateo J, Ong M, Tan DS, Gonzalez MA and de

Bono JS: Appraising iniparib, the PARP inhibitor that never

was-what must we learn? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 10:688–696. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Liu X, Shi Y, Maag DX, Palma JP, Patterson

MJ, Ellis PA, Surber BW, Ready DB, Soni NB, Ladror US, et al:

Iniparib nonselectively modifies cysteine-containing proteins in

tumor cells and is not a bona fide PARP inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res.

18:510–523. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wu HL, Luo ZY, He ZL, Gong Y, Mo M, Ming

WK and Liu GY: All HER2-negative breast cancer patients need gBRCA

testing: Cost-effectiveness and clinical benefits. Br J Cancer.

128:638–646. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler

RK, Audeh MW, Friedlander M, Balmaña J, Mitchell G, Fried G,

Stemmer SM, Hubert A, et al: Olaparib monotherapy in patients with

advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol.

33:244–250. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Dent RA, Lindeman GJ, Clemons M, Wildiers

H, Chan A, McCarthy NJ, Singer CF, Lowe ES, Watkins CL and

Carmichael J: Phase I trial of the oral PARP inhibitor olaparib in

combination with paclitaxel for first- or second-line treatment of

patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast

Cancer Res. 15:R882013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liu JF, Tolaney SM, Birrer M, Fleming GF,

Buss MK, Dahlberg SE, Lee H, Whalen C, Tyburski K, Winer E, et al:

A Phase 1 trial of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor

olaparib (AZD2281) in combination with the anti-angiogenic

cediranib (AZD2171) in recurrent epithelial ovarian or

triple-negative breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 49:2972–2978. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Lee JM, Hays JL, Annunziata CM, Noonan AM,

Minasian L, Zujewski JA, Yu M, Gordon N, Ji J, Sissung TM, et al:

Phase I/Ib study of olaparib and carboplatin in BRCA1 or BRCA2

mutation-associated breast or ovarian cancer with biomarker

analyses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 106:dju0892014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Del Conte G, Sessa C, von Moos R, Viganò

L, Digena T, Locatelli A, Gallerani E, Fasolo A, Tessari A,

Cathomas R and Gianni L: Phase I study of olaparib in combination

with liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced solid tumours.

Br J Cancer. 111:651–659. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Loap P, Loirat D, Berger F, Ricci F,

Vincent-Salomon A, Ezzili C, Mosseri V, Fourquet A, Ezzalfani M and

Kirova Y: Combination of olaparib and radiation therapy for triple

negative breast cancer: Preliminary results of the RADIOPARP phase

1 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 109:436–440. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Loap P, Loirat D, Berger F, Cao K, Ricci

F, Jochem A, Raizonville L, Mosseri V, Fourquet A and Kirova Y:

Combination of Olaparib with radiotherapy for triple-negative

breast cancers: One-year toxicity report of the RADIOPARP Phase I

trial. Int J Cancer. 149:1828–1832. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Loap P, Loirat D, Berger F, Rodrigues M,

Bazire L, Pierga JY, Vincent-Salomon A, Laki F, Boudali L,

Raizonville L, et al: Concurrent Olaparib and radiotherapy in

patients with triple-negative breast cancer: The phase 1 Olaparib

and radiation therapy for triple-negative breast cancer trial. JAMA

Oncol. 8:1802–1808. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Ganz PA, Bandos H, Španić T, Friedman S,

Müller V, Kuemmel S, Delaloge S, Brain E, Toi M, Yamauchi H, et al:

Patient-reported outcomes in OlympiA: A phase III, randomized,

placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant Olaparib in gBRCA1/2 mutations

and high-risk human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative

early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 42:1288–1300. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Plummer R, Jones C, Middleton M, Wilson R,

Evans J, Olsen A, Curtin N, Boddy A, McHugh P, Newell D, et al:

Phase I study of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor,

AG014699, in combination with temozolomide in patients with

advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 14:7917–7923. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Drew Y, Ledermann J, Hall G, Rea D,

Glasspool R, Highley M, Jayson G, Sludden J, Murray J, Jamieson D,

et al: Phase 2 multicentre trial investigating intermittent and

continuous dosing schedules of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

inhibitor rucaparib in germline BRCA mutation carriers with

advanced ovarian and breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 114:723–730. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chopra N, Tovey H, Pearson A, Cutts R,

Toms C, Proszek P, Hubank M, Dowsett M, Dodson A, Daley F, et al:

Homologous recombination DNA repair deficiency and PARP inhibition

activity in primary triple negative breast cancer. Nat Commun.

11:26622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kristeleit R, Leary A, Oaknin A, Redondo

A, George A, Chui S, Seiller A, Liste-Hermoso M, Willis J, Shemesh

CS, et al: PARP inhibition with rucaparib alone followed by

combination with atezolizumab: Phase Ib COUPLET clinical study in

advanced gynaecological and triple-negative breast cancers. Br J

Cancer. 131:820–831. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Sandhu SK, Schelman WR, Wilding G, Moreno

V, Baird RD, Miranda S, Hylands L, Riisnaes R, Forster M, Omlin A,

et al: The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor niraparib (MK4827)

in BRCA mutation carriers and patients with sporadic cancer: A

phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 14:882–892. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

van Andel L, Rosing H, Zhang Z, Hughes L,

Kansra V, Sanghvi M, Tibben MM, Gebretensae A, Schellens JHM and

Beijnen JH: Determination of the absolute oral bioavailability of

niraparib by simultaneous administration of a (14)C-microtracer and

therapeutic dose in cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

81:39–46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM,

Mahner S, Redondo A, Fabbro M, Ledermann JA, Lorusso D, Vergote I,

et al: Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive,

recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 375:2154–2164. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Scott LJ: Niraparib: First global

approval. Drugs. 77:1029–1034. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Wang L, Mason KA, Ang KK, Buchholz T,

Valdecanas D, Mathur A, Buser-Doepner C, Toniatti C and Milas L:

MK-4827, a PARP-1/-2 inhibitor, strongly enhances response of human

lung and breast cancer xenografts to radiation. Invest New Drugs.

30:2113–2120. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Shen Y, Rehman FL, Feng Y, Boshuizen J,

Bajrami I, Elliott R, Wang B, Lord CJ, Post LE and Ashworth A: BMN

673, a novel and highly potent PARP1/2 inhibitor for the treatment

of human cancers with DNA repair deficiency. Clin Cancer Res.

19:5003–5015. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Litton JK, Beck JT, Jones JM, Andersen J,

Blum JL, Mina LA, Brig R, Danso M, Yuan Y, Abbattista A, et al:

Neoadjuvant talazoparib in patients with germline BRCA1/2

mutation-positive, early-stage triple-negative breast cancer:

Results of a phase II study. Oncologist. 28:845–855. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Li Y, Li L, Fu H, Yao Q, Wang L and Lou L:

Combined inhibition of PARP and ATR synergistically potentiates the

antitumor activity of HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate in

HER2-positive cancers. Am J Cancer Res. 13:161–175. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Kozono DE, Stinchcombe TE, Salama JK,

Bogart J, Petty WJ, Guarino MJ, Bazhenova L, Larner JM, Weiss J,

DiPetrillo TA, et al: Veliparib in combination with

carboplatin/paclitaxel-based chemoradiotherapy in patients with

stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 159:56–65. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

O'Reilly EM, Lee JW, Zalupski M, Capanu M,

Park J, Golan T, Tahover E, Lowery MA, Chou JF, Sahai V, et al:

Randomized, multicenter, phase II trial of gemcitabine and

cisplatin with or without veliparib in patients with pancreas

adenocarcinoma and a germline BRCA/PALB2 mutation. J Clin Oncol.

38:1378–1388. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Hussain M, Carducci MA, Slovin S, Cetnar

J, Qian J, McKeegan EM, Refici-Buhr M, Chyla B, Shepherd SP,

Giranda VL and Alumkal JJ: Targeting DNA repair with combination

veliparib (ABT-888) and temozolomide in patients with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Invest New Drugs. 32:904–912.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Gojo I, Beumer JH, Pratz KW, McDevitt MA,

Baer MR, Blackford AL, Smith BD, Gore SD, Carraway HE, Showel MM,

et al: A phase 1 study of the PARP inhibitor veliparib in

combination with temozolomide in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin

Cancer Res. 23:697–706. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Zhang Q, Shao B, Tong Z, Ouyang Q, Wang Y,

Xu G, Li S and Li H: A phase Ib study of camrelizumab in

combination with apatinib and fuzuloparib in patients with

recurrent or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Med.

20:3212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Liu Y, Wang W, Yin R, Zhang Y, Zhang Y,

Zhang K, Pan H, Wang K, Lou G, Li G, et al: A phase 1 trial of

fuzuloparib in combination with apatinib for advanced ovarian and

triple-negative breast cancer: Efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics

and germline BRCA mutation analysis. BMC Med. 21:3762023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Friedlander M, Meniawy T, Markman B,

Mileshkin L, Harnett P, Millward M, Lundy J, Freimund A, Norris C,

Mu S, et al: Pamiparib in combination with tislelizumab in patients

with advanced solid tumours: Results from the dose-escalation stage

of a multicentre, open-label, phase 1a/b trial. Lancet Oncol.

20:1306–1315. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Lord CJ and Ashworth A: Mechanisms of

resistance to therapies targeting BRCA-mutant cancers. Nat Med.

19:1381–1388. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang

Y, Doroshow JH, Ji J, Takeda S and Pommier Y: Trapping of PARP1 and

PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res. 72:5588–5599. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Damale MG, Pathan SK, Shinde DB, Patil RH,

Arote RB and Sangshetti JN: Insights of tankyrases: A novel target

for drug discovery. Eur J Med Chem. 207:1127122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Yu M, Yang Y, Sykes M and Wang S:

Small-molecule inhibitors of tankyrases as prospective therapeutics

for cancer. J Med Chem. 65:5244–5273. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Smith S, Giriat I, Schmitt A and de Lange

T: Tankyrase, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres.

Science. 282:1484–1487. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Rottenberg S, Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A,

van der Burg E, Nygren AO, Zander SA, Derksen PW, de Bruin M,

Zevenhoven J, Lau A, et al: High sensitivity of BRCA1-deficient

mammary tumors to the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 alone and in

combination with platinum drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

105:17079–17084. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Abkevich V, Timms KM, Hennessy BT, Potter

J, Carey MS, Meyer LA, Smith-McCune K, Broaddus R, Lu KH, Chen J,

et al: Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict

homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian

cancer. Br J Cancer. 107:1776–1782. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Wang S, Chang CW, Huang J, Zeng S, Zhang

X, Hung MC and Hou J: Gasdermin C sensitizes tumor cells to PARP

inhibitor therapy in cancer models. J Clin Invest. 134:e1668412024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Stringer-Reasor EM, May JE, Olariu E,

Caterinicchia V, Li Y, Chen D, Della Manna DL, Rocque GB, Vaklavas

C, Falkson CI, et al: An open-label, pilot study of veliparib and

lapatinib in patients with metastatic, triple-negative breast

cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 23:302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Ray Chaudhuri A, Callen E, Ding X, Gogola

E, Duarte AA, Lee JE, Wong N, Lafarga V, Calvo JA, Panzarino NJ, et

al: Replication fork stability confers chemoresistance in

BRCA-deficient cells. Nature. 535:382–387. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Tan Q and Xu X: PTIP UFMylation promotes

replication fork degradation in BRCA1-deficient cells. J Biol Chem.

300:1073122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Tian T, Chen J, Zhao H, Li Y, Xia F, Huang

J, Han J and Liu T: UFL1 triggers replication fork degradation by

MRE11 in BRCA1/2-deficient cells. Nat Chem Biol. 20:1650–1661.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, Viale G,

Fumagalli D, Rastogi P, Gelber RD, de Azambuja E, Fielding A,

Balmaña J, et al: Adjuvant olaparib for patients with BRCA1- or

BRCA2-mutated breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 384:2394–2405. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Gelmon KA, Fasching PA, Couch FJ, Balmaña

J, Delaloge S, Labidi-Galy I, Bennett J, McCutcheon S, Walker G and

O'Shaughnessy J; Collaborating Investigator, : Clinical

effectiveness of olaparib monotherapy in germline BRCA-mutated,

HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in a real-world setting:

Phase IIIb LUCY interim analysis. Eur J Cancer. 152:68–77. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Pusztai L, Yau C, Wolf DM, Han HS, Du L,

Wallace AM, String-Reasor E, Boughey JC, Chien AJ, Elias AD, et al:

Durvalumab with olaparib and paclitaxel for high-risk HER2-negative

stage II/III breast cancer: Results from the adaptively randomized

I-SPY2 trial. Cancer Cell. 39:989–998.e5. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Batalini F, Xiong N, Tayob N, Polak M,