Tumor immunotherapy is a crucial treatment approach

following surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Currently,

immunotherapy is considered to be the most common treatment method

for tumors (1). Although tumor

cells cause a strong immune response, cancer persists, which may be

attributed to the fact that the immune response against tumor cells

is insufficient to prevent the development of cancer or that the

transient immune response triggers specific immune tolerance

mechanisms in tumor cells (2). A

healthy immune system maintains immune balance using co-suppressing

receptors and their ligands, known as immune checkpoint blockers

(ICBs). Therefore, tumor cells can escape immune attacks by

breaking the balance of the immune checkpoints (3). In recent years, the successful

application of combined signal receptor-targeted immune therapy has

attracted widespread attention (4,5).

Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated that monoclonal

antibodies (mAb) targeting the inhibitory receptors cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell

death-1 (PD-1) exhibit favorable therapeutic effects in a variety

of human malignancies, including melanoma, non-small cell lung

cancer, renal cell carcinoma, bladder cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma

(6–8). However, despite the promising results

achieved by ICBs, there is still a considerable number of patients

who cannot benefit from the currently available therapies (9). To further exploit the advantages of

immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, it is necessary to explore

novel immune checkpoints as therapeutic targets for patients with

cancer (10).

In recent years, nectin receptors and nectin-like

molecule (NECL) proteins have received extensive attention as

targets for cancer immunotherapy (11). NECLs are more extensively expressed

than nectins and exert more abundant functions (12). NECL-1 and NECL-4 mediate the

interaction between axons and participate in Schwann cell

differentiation and myelination (12,13).

NECL-2 functions as a tumor suppressor and immune surveillance

modulator (14). NECL-5 serves a

crucial role among NECLs due to its unique expression profile as

described below. NECL-5 is also known as CD155. CD155 also serves

as a poliovirus receptor (PVR), which promotes the migration and

proliferation of tumor cells (14,15).

CD155 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, characterized

by the presence of an immunoglobulin domain V and C1-like and C2

domains in the extracellular region (16). CD155 has four splicing isoforms,

defined as α, β, γ and δ. The α and δ isoforms contain a

transmembrane domain, while the α isoform contains a longer

C-terminal domain and an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory

motif (ITIM) necessary for the intrinsic biology of tumor cells

(17). However, the β and γ

subtypes lack transmembrane domains, and their biological functions

have not been elucidated (17).

CD155 can recruit protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 via the ITIM

domain to initiate signal transduction (18,19),

cell adhesion (20), motility

(18,21), proliferation and survival (22). CD155 is also involved in tumor

immune response. When CD155 is upregulated in different types of

tumor cells, the activating receptor CD226 and the inhibitory

receptors T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT)

and CD96, which are expressed on the cell surface of T and natural

killer (NK) cells, recognize and bind to tumor cells (23). CD155 exhibits the highest binding

capacity with TIGIT, followed medium binding capacity with CD96 and

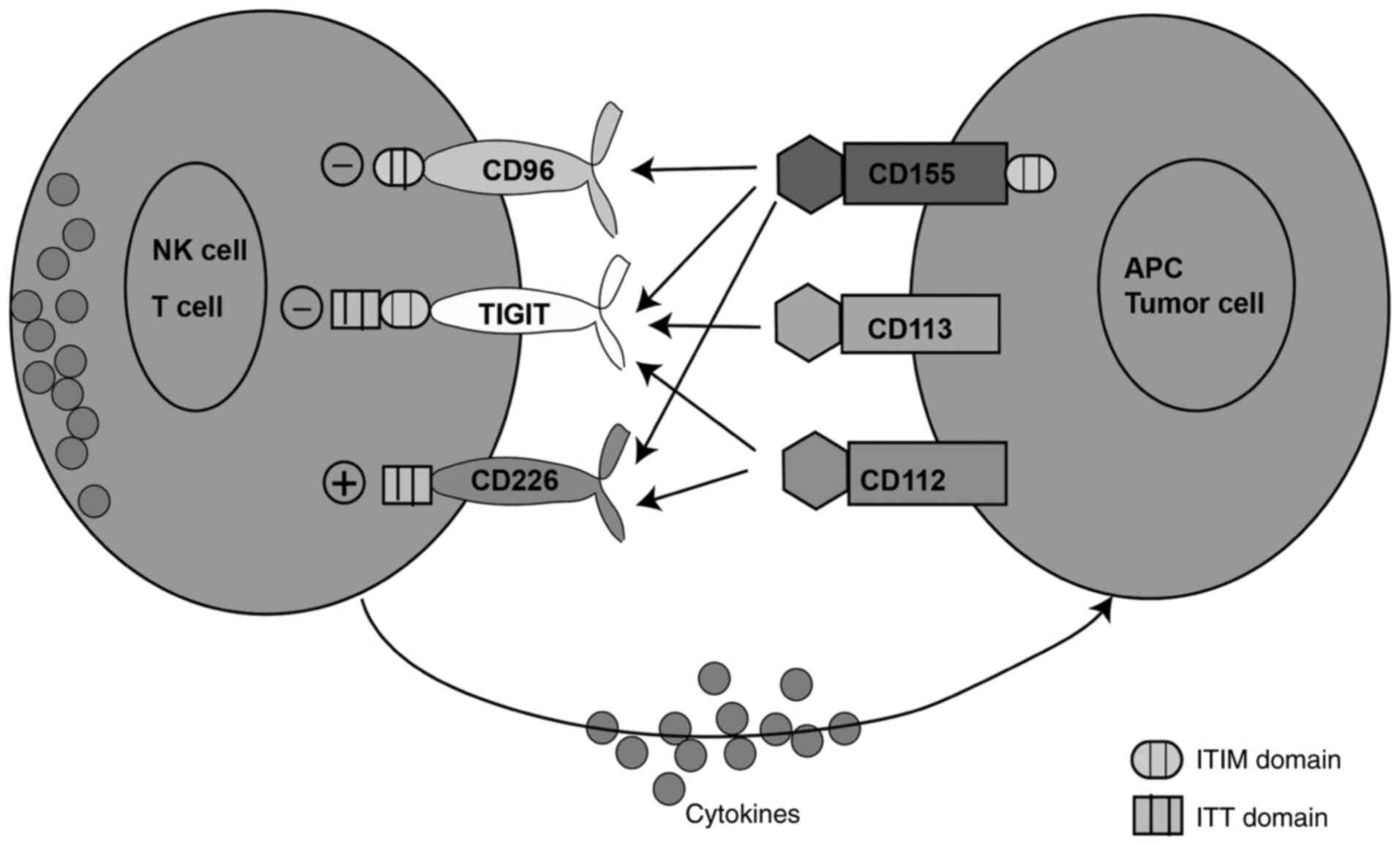

the lowest binding capacity with CD226 (Fig. 1) (24,25).

The increased expression of CD155 in tumors may be

caused by different mechanisms. Firstly, the chemotherapy approach

used at present to treat patients with multiple myeloma (MM)

damages the DNA of tumor cells and inhibits the expression of DNA

polymerase, thereby affecting the replication capacity of highly

proliferating malignant cells. However, standard-dose chemotherapy

usually causes a powerful immunosuppressive effect (35,36).

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) is a serine-threonine kinase

activated when cells are exposed to DNA double-strand breaks. ATM

is involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis and DNA repair

(37). Similar to ATM, Ataxia

telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) serves a vital role

in cell cycle signal transduction and DNA damage response (38). In MM cells treated with doxorubicin

and melphalan, CD155 was upregulated at both the protein and mRNA

levels, depending on the activation status of the DNA damage

sensors, ATM and ATR (36).

Secondly, it has been suggested that the Ras

oncogene mediates the upregulation of CD155 via the

Raf/MEK/ERK/activator protein-1 signaling pathway (39). Therefore, a MEK inhibitor can block

the Ras-mediated activation of the CD155 promoter. Additionally, it

has been demonstrated that fibroblast growth factor also

upregulates the expression of CD155 via the same signaling pathway

(39).

Thirdly, sonic hedgehog (Shh), a vital morphogen, is

co-expressed in the same locations with CD155 during development.

The Shh signaling pathway serves an important role in cell

differentiation and proliferation (40). Abnormal activation of Shh-Gli has

been associated with different types of human cancer (40,41). A

previous study indicated that treatment of human NTERA-2 cells with

purified Shh protein upregulated the mRNA expression of CD155

(42).

Fourthly, immune cells expressing CD155 have been

detected in primary tumors and tumor-infiltrating leukocytes of the

draining lymph nodes; however, it seems to be mainly limited to

myeloid cells (43). Stimulation of

murine bone marrow-derived macrophages and B lymphocytes with

lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been indicated to upregulate the

NF-κB-dependent CD155 expression in vitro (44–46).

Furthermore, Toll-like receptor agonists, including LPS, have been

reported to increase the expression of CD155 in dendritic cells

(DCs) (47).

High expression of CD155 is associated with the

invasive and migratory abilities of tumor cells. Focal adhesions

are composed of integrins and related cytoplasmic plaque proteins,

including talin, vinculin, α-actin, tenascin and paxillin and

numerous protein kinases. Integrins interact with the extracellular

matrix (ECM) (48). In

vitro, ECM proteins bind to CD155, suggesting that CD155 may

mediate cell-matrix interactions (20). Stimulation of CD155α with its ligand

has been indicated to promote the Src kinase-mediated

phosphorylation of ITIM, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and paxillin,

ultimately inhibiting cell adhesion and enhancing cell

proliferation. The activation of CD155α also enhanced the

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-mediated cell migration.

Taken together, these findings indicated that CD155 could regulate

cell adhesion and movement (Fig.

2A) (18). CD155, PDGF receptor

and integrin αvβ3 synergistically participate in the formation of a

ternary complex on the leading edge of a cell (49–51).

Ternary complexes serve a vital role in the dynamics of the leading

edge. It has been demonstrated that this ternary complex promotes

the activation of Src and DNA-binding protein RAP1, which in turn

activates Rac and inhibits RhoA, thereby resulting in improved cell

movement (16). In addition, a

previous study has revealed that CD155 could regulate cell

proliferation via enhancing the activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK

signaling pathway (22). Protein

sprouty homolog 2 (SPRY2) is a negative regulator of the growth

factor-induced cell proliferation (52,53).

SPRY2 is phosphorylated by the Src kinase following growth factor

signaling, thereby inhibiting the activation of growth

factor-induced Ras signals (52).

CD155 prolongs the activation of the proliferation-associated

signals induced by the inhibition of SPRY2, which is a negative

regulator of the Ras/Raf/MAPK signaling pathway involved in the

regulation of organogenesis, differentiation, cell migration and

proliferation (54). As illustrated

in Fig. 2B, SPRY2 can be released

from CD155 and phosphorylated by Src to inhibit the Ras pathway and

cell proliferation (16).

Additionally, CD155 promotes tumor growth. A

previous study has demonstrated that CD155 enhanced the activation

of the serum-induced Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, upregulated

cyclin D2 and E, downregulated p27Kip1 and finally inhibited the

G0/G1 cell cycle arrest of NIH3T3 cells

(Fig. 2C) (22). Furthermore, knockdown of CD155

reduced the size and weight of tumors in colon cancer models and

attenuated the metastasis rate of tumors in several other mouse

tumor models (6,43,55).

To identify costimulatory or inhibitory molecules on

activated human T cells, Yu et al (24) conducted a genome search to recognize

genes with immunomodulatory receptor protein domains in T helper

(Th)17 cells. They identified a specific gene expressed on T and NK

cells, which encoded a protein containing variable immunoglobulin

domains and an ITIM, which was named TIGIT. It is considered that

TIGIT is an inhibitory receptor mainly expressed on NK,

CD8+ T, CD4+ T cells and Tregs (24). TIGIT consists of an extracellular

immunoglobulin variable domain, a type I transmembrane domain, a

short intracellular domain with an ITIM and an immunoglobulin tail

tyrosine (ITT)-like motif (24). It

has been indicated that TIGIT can bind to three ligands on tumor

cells, namely CD155, CD112 and CD113. CD155 is a high-affinity

ligand of TIGIT (Fig. 1) (24,56).

TIGIT acts as a receptor for PVR and induces intracellular

signaling, while it may serve as a competitive inhibitor of CD226

(24,56).

It has been reported that TIGIT is upregulated in

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in acute myeloid leukemia

(AML), melanoma, multiple myeloma, non-small cell lung cancer,

gastric cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (56–64).

It has been demonstrated that the expression of TIGIT was

upregulated in CD8+ T lymphocytes and tumor-infiltrating

Tregs and NK cells (65–67). TIGIT has been associated with poor

clinical outcomes in cancer. For example, the expression of TIGIT

in TILs of patients with melanoma and CD8+ T cells in

the peripheral blood of patients with gastric cancer was associated

with tumor metastasis and poor survival (62,68,69).

Furthermore, a strong association between the expression of TIGIT

on CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood and the

recurrence of AML after transplantation has been revealed (58). In addition, a recent study on

endometrial cancer demonstrated that the high expression of TIGIT

on tumor-infiltrating NK cells was positively correlated with the

severity of the disease (Table I)

(70).

Currently, several mechanisms of the

CD155/TIGIT-mediated inhibition of effector T and NK cells have

been discovered. Immunoactivating receptor CD226 is a

co-stimulatory molecule expressed on NK cells, T lymphocytes,

monocytes and B cells, which competes with TIGIT for binding with

CD155 (71). TIGIT directly

interacts with CD226 on the cell surface and attenuates the ability

of CD226 to form homodimers. These results indicate that TIGIT can

reduce the activity of CD226 during the anti-tumor and anti-viral T

cell response (57). In NK cells,

TIGIT has been demonstrated to mediate inhibitory signals via ITIM

(56), while its engagement could

directly inhibit T cell activation and proliferation (Fig. 3A) (55,71,72).

CD155 is also expressed on DCs. It has been suggested that the

CD155-TIGIT interaction can regulate T cell-driven immune responses

via inducing interleukin IL-10 expression in DCs. Furthermore,

TIGIT-modified mature DCs can promote the production of IL-10 and

attenuate that of IL-12 (Fig. 3B)

(24). TIGIT is also highly

expressed in Tregs (66). Indeed,

it has been revealed that compared with TIGIT− Tregs,

the inhibitory effect of TIGIT+ Tregs was enhanced. In

addition, TIGIT+ Tregs were indicated to produce a

higher amount of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 compared with

TIGIT− Tregs, which not only contributed to

immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment but also promoted a

tolerogenic phenotype in DCs (Fig.

3C) (73). Additionally, IL-10

and fibrinogen-like protein 2 (Fgl2) secreted by TIGIT+

Treg cells could synergistically inhibit the secretion of IL-12 and

IL-23 by activated DCs, thereby inhibiting the Th1 and Th17 immune

responses (73). It has been also

demonstrated that TIGIT+ Treg cells secreted high

amounts of Fgl2, resulting in the inhibition of Th1 and Th17 cell

differentiation, but not Th2 differentiation (73–74).

Th2 cells can promote type 2 tumor-associated macrophage (TAM2)

differentiation by secreting IL-4. Therefore, it was demonstrated

that TAM2 suppressed T cell immune responses via secreting

inhibitory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, and depleted

nutrients in the microenvironment via secreting arginase 1 (Arg1),

indoleamine 2 and 3-dioxygenase, further weakening T cell function

(Fig. 3D) (75).

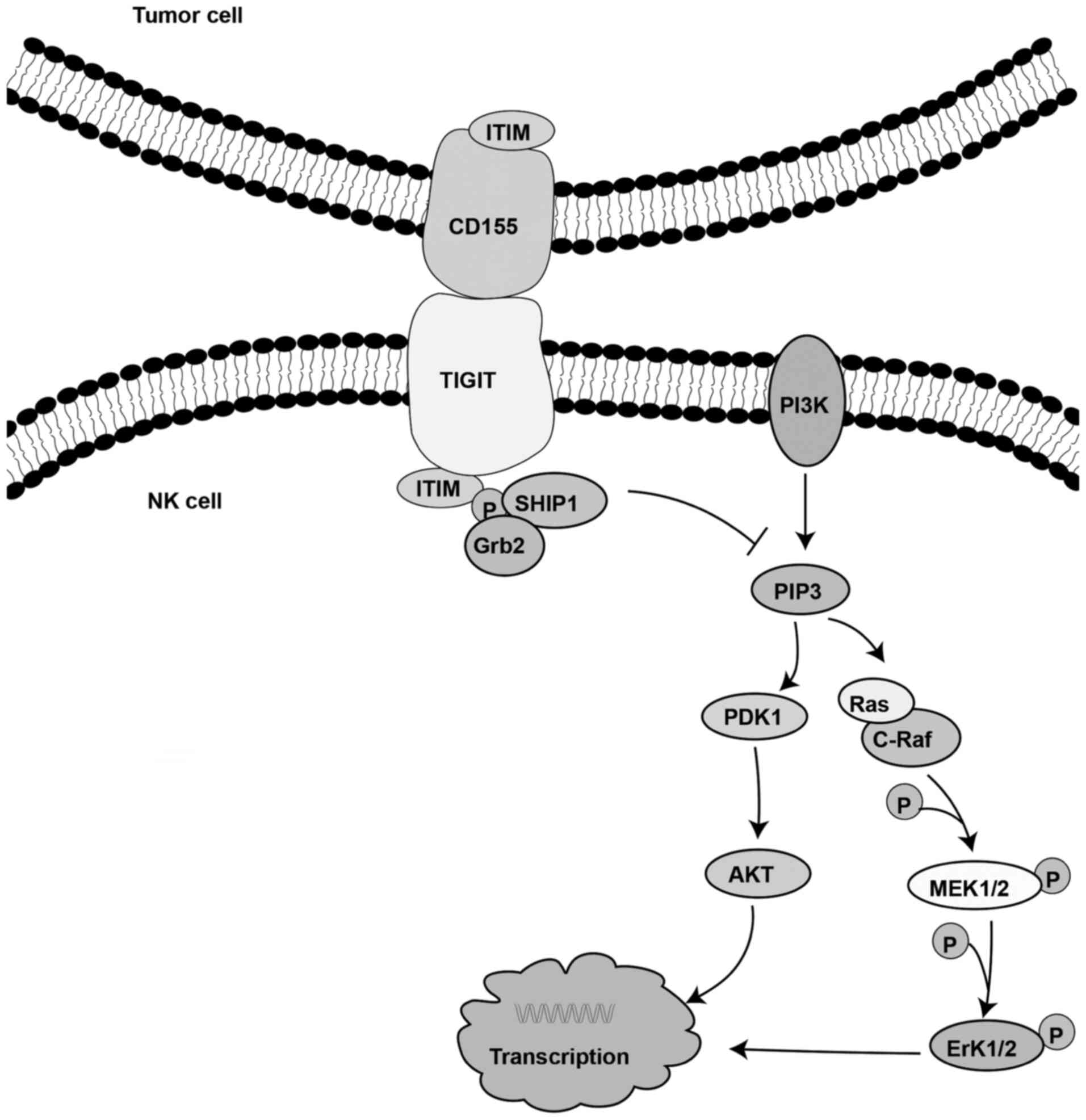

TIGIT expressed on NK cells binds with its ligand on

tumor cells to directly inhibit NK cell toxicity (56). It has been reported that the

decreased NK cell activity is mediated by the phosphorylation of

the ITT-like domain of the cytoplasmic tail of TIGIT. Following

binding of TIGIT to its ligand, the ITT-like motif is

phosphorylated at Tyr225. Subsequently, the complex binds to the

cytosolic adaptor growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) and

recruits SH2-containing inositol phosphatase-1 (SHIP-1), which in

turn promotes signal inhibition, thereby attenuating the cytotoxic

activity of NK cells (76). It has

also been demonstrated that TIGIT recruits SHIP-1 to prematurely

terminate the activation of AKT, ERK and MEK, thereby inhibiting NK

cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 4)

(76).

β-arrestins are common inhibitory protein. The

interaction of β-arrestins and with their partners can regulate

cell positioning, translocation and stability, while they are also

involved in the regulation of the immune response (77). Emerging evidence has suggested that

IκBα can directly interact with β-arrestin 2 to prevent

phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα (77). Furthermore, TNF receptor-associated

factor 6 (TRAF6) serves an important role in NF-κB signal

transduction (77–79). Therefore, a previous study

demonstrated that β-arrestin 2 could bind to the ITT-like motif of

phosphorylated TIGIT, recruit SHIP-1 and reduce TRAF6

autoubiquitination, thereby preventing NF-κB activation and

inhibiting IFN-γ production. However, SHIP-1 silencing could

restore IFN-γ production (Fig. 5A)

(77).

It has been reported that the CD155/TIGIT

interaction reduces the activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway,

resulting in the inhibition of metabolism and cytokine production.

In a co-culture system of the human gastric cancer cells SGC7901

with CD8+ T cells, downregulation of CD155 in SGC7901

cells increased the phosphorylation of AKT, p70S6 kinase and 4E

binding protein 1 in CD8+ T cells (63). In addition, glucose uptake, lactic

acid production and IFN-γ secretion were also increased.

Furthermore, TIGIT has been indicated to inhibit the metabolic

pathway in CD8+ T cells (63). TIGIT blockade was demonstrated to

promote the activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway, leading to

metabolism upregulation and cytokine production in CD8+

T cells. These findings indicated that CD155/TIGIT signaling in

CD8+ T cells reduced the activation of the AKT/mTOR

pathway, thereby resulting in metabolism downregulation and

suppression of cytokine production (Fig. 5B) (63).

In mouse tumor models, TIGIT deficiency

significantly attenuated the proliferation of B16F10 melanoma and

MC38 colon cancer cells, compared with wild-type controls (65). In addition, a recent study has

demonstrated that the serum levels of monoclonal immunoglobulin

proteins in TIGIT-deficient mice increased, thus reducing the tumor

burden and prolonging the survival period of mice, suggesting that

TIGIT inhibited the anti-tumor responses in multiple myeloma.

Importantly, blocking TIGIT with monoclonal antibodies could

enhance the function of CD8+ T effector cells and

inhibit the development of multiple myeloma (60). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that

treatment with anti-TIGIT could significantly delay tumor growth in

a mouse model of transgenic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

and enhance the anti-tumor immune response via activating

CD8+ T effector cells and reducing the number of Tregs.

In vitro, co-culture studies revealed that anti-TIGIT

treatment could significantly eliminate the immunosuppressive

ability of myeloid suppressor cells via downregulating Arg1 and

preventing Treg inhibition by reducing the secretion of TGF-β1

(33). In AML, TIGIT downregulation

using the small interfering RNA technology, could inhibit the

immunosuppressive effect of TIGIT+ CD8+ T

cells in the blood, thereby resulting in increased secretion of

IFN-γ and TNF-α and decreased apoptosis (58).

A clinical trial has indicated that the mismatch

repair status can predict the clinical benefit of treatment with

the anti-PD-1 mAb pembrolizumab. However, one third of patients

still did not respond to anti-PD-1 therapy (80). Preclinical studies on the effect of

TIGIT on regulating anti-tumor immune responses indicated that

TIGIT combined with current immunotherapy was a promising target.

For example, it has been suggested that a combined treatment

approach with TIGIT and PD-1 or T-cell immunoglobulin mucin

receptor 3 (TIM-3) on malignant tumors was more beneficial compared

with a single-targeted one (11,65).

Treatment of patients with TIGIT/PD-1 co-blockade also enhanced the

expansion and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells in gastric

cancer (63), non-Hodgkin lymphoma

(81) and glioblastoma (82) compared with a single blockade

therapy. Furthermore, the combination of anti-TIGIT therapy with

other immune checkpoint inhibitors has been also examined in mouse

models. For instance, treatment of TIGIT−/− mice with

anti-TIM-3 antibodies significantly reduced tumor growth compared

with TIGIT−/− deficiency alone (65). Blocking TIGIT could also increase

the cytokine expression (such as TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2) of

TIGIT+ cells; however, this was less effective than the

combined blockade of TIGIT, PD-1 and TIM-3 (83).

Immunotherapy can provide an important anti-tumor

response in patients with advanced and metastatic tumors. However,

even in sensitive types of tumors, a large proportion of patients

does not respond to these therapies. Therefore, novel immune

targets as a supplement to immunotherapy are urgently needed. TIGIT

is considered a promising target that exhibits an immunomodulatory

role in several processes involved in carcinogenesis (84). It is hypothesized that the combined

application of anti-TIGIT and anti-PD-1 will have a synergistic

effect similar to that of the combined application of anti-PD-1 and

anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in melanoma, which can increase the response

rate to therapy (85). A growing

number of preclinical studies have indicated that combining

anti-TIGIT with other immunological agents can increase the

anti-tumor response in patients (Table

II). Therefore, more favorable results in future studies based

on the application of anti-TIGIT therapy are anticipated.

Not applicable.

The study was conducted at Qilu Hospital, Shandong

University and was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81572559) and the Key Research

Project of Shandong Province (grant no. 2017CXGC1210).

Not applicable.

LL wrote the manuscript; XWY and YS designed and

drew the figures; SH and JHZ edited the figures; YZZ conceived and

designed the study. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Trapani J and Darcy P: Immunotherapy of

cancer. Aust Fam Physician. 46:194–199. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Willimsky G and Blankenstein T: Sporadic

immunogenic tumours avoid destruction by inducing T-cell tolerance.

Nature. 437:141–146. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang G, Tai R, Wu Y, Yang S, Wang J, Yu X,

Lei L, Shan Z and Li N: The expression and immunoregulation of

immune checkpoint molecule VISTA in autoimmune diseases and

cancers. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 52:1–14. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chen L and Flies DB: Molecular mechanisms

of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol.

13:227–242. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zou W, Wolchok JD and Chen L: PD-L1

(B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms,

response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med.

8:328rv3242016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Smyth MJ, Ngiow SF, Ribas A and Teng MWL:

Combination cancer immunotherapies tailored to the tumour

microenvironment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 13:143–158. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kruger S, Ilmer M, Kobold S, Cadilha BL,

Endres S, Ormanns S, Schuebbe G, Renz BW, D'Haese JG, Schloesser H,

et al: Advances in cancer immunotherapy 2019-latest trends. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 38:2682019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, Lamine

F, Maillard M, Fraga M, Shabafrouz K, Ribi C, Cairoli A,

Guex-Crosier Y, et al: Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint

inhibitors: Epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 16:563–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Darvin P, Toor SM, Nair VS and Elkord E:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Recent progress and potential

biomarkers. Exp Mol Med. 50:1652018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sharma P and Allison JP: Immune checkpoint

targeting in cancer therapy: Toward combination strategies with

curative potential. Cell. 161:205–214. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dougall WC, Kurtulus S, Smyth MJ and

Anderson AC: TIGIT and CD96: New checkpoint receptor targets for

cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 276:112–120. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kakunaga S, Ikeda W, Itoh S,

Deguchi-Tawarada M, Ohtsuka T, Mizoguchi A and Takai Y: Nectin-Like

molecule-1/TSLL1/SynCAM3: A neural tissue-specific

immunoglobulin-like cell-cell adhesion molecule localizing at

non-junctional contact sites of presynaptic nerve terminals, axons

and glia cell processes. J Cell Sci. 118:1267–1277. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Spiegel I, Adamsky K, Eshed Y, Milo R,

Sabanay H, Sarig-Nadir O, Horresh I, Scherer SS, Rasband MN and

Peles E: A central role for Necl4 (SynCAM4) in Schwann cell-axon

interaction and myelination. Nat Neurosci. 10:861–869. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kuramochi M, Fukuhara H, Nobukuni T, Kanbe

T, Maruyama T, Ghosh HP, Pletcher M, Isomura M, Onizuka M, Kitamura

T, et al: TSLC1 is a tumor-suppressor gene in human non-small-cell

lung cancer. Nat Genet. 27:427–430. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fujito T, Ikeda W, Kakunaga S, Minami Y,

Kajita M, Sakamoto Y, Monden M and Takai Y: Inhibition of cell

movement and proliferation by cell-cell contact-induced interaction

of necl-5 with nectin-3. J Cell Biol. 171:165–173. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Takai Y, Miyoshi J, Ikeda W and Ogita H:

Nectins and nectin-like molecules: Roles in contact inhibition of

cell movement and proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 9:603–615.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Koike S, Horie H, Ise I, Okitsu A, Yoshida

M, Iizuka N, Takeuchi K, Takegami T and Nomoto A: The poliovirus

receptor protein is produced both as membrane-bound and secreted

forms. EMBO J. 9:3217–3224. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Oda T, Ohka S and Nomoto A: Ligand

stimulation of CD155alpha inhibits cell adhesion and enhances cell

migration in fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

319:1253–1264. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yusa Si, Catina TL and Campbell KS: SHP-1-

and phosphotyrosine-independent inhibitory signaling by a killer

cell Ig-like receptor cytoplasmic domain in human NK cells. J

Immunol. 168:5047–5057. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lange R, Peng X, Wimmer E, Lipp M and

Bernhardt G: The poliovirus receptor CD155 mediates cell-to-matrix

contacts by specifically binding to vitronectin. Virology.

285:218–227. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Reymond N, Imbert AM, Devilard E, Fabre S,

Chabannon C, Xerri L, Farnarier C, Cantoni C, Bottino C, Moretta A,

et al: DNAM-1 and PVR regulate monocyte migration through

endothelial junctions. J Exp Med. 199:1331–1341. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kakunaga S, Ikeda W, Shingai T, Fujito T,

Yamada A, Minami Y, Imai T and Takai Y: Enhancement of serum- and

platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell proliferation by

necl-5/tage4/poliovirus receptor/CD155 through the ras-raf-MEK-ERK

signaling. J Biol. 27:36419–36425. 2004.

|

|

23

|

Molfetta R, Zitti B, Lecce M, Milito ND,

Stabile H, Fionda C, Cippitelli M, Gismondi A, Santoni A and

Paolini R: CD155: A multi-functional molecule in tumor progression.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:9222020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, Francesco M,

Chiang E, Irving B, Tom I, Ivelja S, Refino CJ, Clark H, et al: The

surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the

generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol.

10:48–57. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Deuss FA, Watson GM, Fu Z, Rossjohn J and

Berry R: Structural basis for CD96 immune receptor recognition of

nectin-like protein-5, CD155. Structure. 5:219–228. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Bevelacqua V, Bevelacqua Y, Candido S,

Skarmoutsou E, Amoroso A, Guarneri C, Strazzanti A, Gangemi P,

Mazzarino MC, D'Amico F, et al: Nectin like-5 overexpression

correlates with the malignant phenotype in cutaneous melanoma.

Oncotarget. 3:882–892. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nakai R, Maniwa Y, Tanaka Y, Nishio W,

Yoshimura M, Okita Y, Ohbayashi C, Satoh N, Ogita H, Takai Y and

Hayashi Y: Overexpression of necl-5 correlates with unfavorable

prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci.

101:1326–1330. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nishiwada S, Sho M, Yasuda S, Shimada K,

Yamato I, Akahori T, Kinoshita S, Nagai M, Konishi N and Nakajima

Y: Clinical significance of CD155 expression in human pancreatic

cancer. Anticancer Res. 35:2287–2297. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Smazynski J, Hamilton PT, Thornton S,

Milne K, Wouters MC, Webb JR and Nelson BH: The immune suppressive

factors CD155 and PD-L1 show contrasting expression patterns and

immune correlates in ovarian and other cancers. Gynecol Oncol.

158:167–177. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pende D, Spaggiari GM, Marcenaro S,

Martini S, Rivera P, Capobianco A, Falco M, Lanino E, Pierri I,

Zambello R, et al: Analysis of the receptor-ligand interactions in

the natural killer-mediated lysis of freshly isolated myeloid or

lymphoblastic leukemias: Evidence for the involvement of the

poliovirus receptor (CD155) and nectin-2 (CD112). Blood.

105:2066–2073. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Gromeier M, Lachmann S, Rosenfeld MR,

Gutin PH and Wimmer E: Intergeneric poliovirus recombinants for the

treatment of malignant glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

97:6803–6808. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang DW, Huang M, Lin XS and Huang Q:

CD155 expression and its correlation with clinicopathologic

characteristics, angiogenesis, and prognosis in human

cholangiocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 10:3817–3825. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wu L, Mao L, Liu JF, Chen L, Yu GT, Yang

LL, Wu H, Bu LL, Kulkarni AB, Zhang WF and Sun ZJ: Blockade of

TIGIT/CD155 signaling reverses t-cell exhaustion and enhances

antitumor capability in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancer Immunol Res. 7:1700–1713. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Iguchi-Manaka A, Okumura G, Kojima H, Cho

Y, Hirochika R, Bando H, Sato T, Yoshikawa H, Hara H and Shibuya A:

Increased soluble CD155 in the serum of cancer patients. PLoS One.

11:e01529822016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Soriani A, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, Iannitto

ML, Ricciardi MR, Di Gialleonardo V, Cippitelli M, Fionda C,

Petrucci MT, Guarini A, et al: ATM-ATR-Dependent up-regulation of

DNAM-1 and NKG2D ligands on multiple myeloma cells by therapeutic

agents results in enhanced NK-cell susceptibility and is associated

with a senescent phenotype. Blood. 113:3503–3511. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Soriani A, Fionda C, Ricci B, Iannitto ML,

Cippitelli M and Santoni A: Chemotherapy-Elicited upregulation of

NKG2D and DNAM-1 ligands as a therapeutic target in multiple

myeloma. Oncoimmunology. 2:e266632014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Lee JH and Paull TT: Activation and

regulation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA double-strand

breaks. Oncogene. 26:7741–7748. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vauzour D, Vafeiadou K, Rice-Evans C,

Cadenas E and Spencer JP: Inhibition of cellular proliferation by

the genistein metabolite 5,7,3′,4′-tetrahydroxyisoflavone is

mediated by DNA damage and activation of the ATR signalling

pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 468:159–166. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hirota T, Irie K, Okamoto R, Ikeda W and

Takai Y: Transcriptional activation of the mouse

necl-5/tage4/PVR/CD155 gene by fibroblast growth factor or

oncogenic ras through the raf-MEK-ERK-AP-1 pathway. Oncogene.

24:2229–2235. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Rimkus TK, Carpenter RL, Qasem S, Chan M

and Lo HW: Targeting the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway: Review

of smoothened and GLI inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 8:222016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Athar M, Li C, Kim AL, Spiegelman VS and

Bickers DR: Sonic hedgehog signaling in basal cell nevus syndrome.

Cancer Res. 74:4967–4975. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Solecki DJ, Gromeier M, Mueller S,

Bernhardt G and Wimmer E: Expression of the human poliovirus

receptor/CD155 gene is activated by sonic hedgehog. J Biol Chem.

277:25697–25702. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li XY, Das I, Lepletier A, Addala V, Bald

T, Stannard K, Barkauskas D, Liu J, Aguilera AR, Takeda K, et al:

CD155 loss enhances tumor suppression via combined host and

tumor-intrinsic mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 128:2613–2625. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Escalante NK, von Rossum A, Lee M and Choy

JC: CD155 on human vascular endothelial cells attenuates the

acquisition of effector functions in CD8 T cells. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 31:1177–1184. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kamran N, Takai Y, Miyoshi J, Biswas SK,

Wong JSB and Gasser S: Toll-Like receptor ligands induce expression

of the costimulatory molecule CD155 on antigen-presenting cells.

PLoS One. 8:e544062013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Pende D, Castriconi R, Romagnani P,

Spaggiari GM, Marcenaro S, Dondero A, Lazzeri E, Lasagni L, Martini

S, Rivera P, et al: Expression of the DNAM-1 ligands, Nectin-2

(CD112) and poliovirus receptor (CD155), on dendritic cells:

Relevance for natural killer-dendritic cell interaction. Blood.

107:2030–2036. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Gilfillan S, Chan CJ, Cella M, Haynes NM,

Rapaport AS, Boles KS, Andrews DM, Smyth MJ and Colonna M: DNAM-1

promotes activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes by nonprofessional

antigen-presenting cells and tumors. J Exp Med. 205:2965–2973.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Gumbiner BM: Cell adhesion: The molecular

basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 84:345–357.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Minami Y, Ikeda W, Kajita M, Fujito T,

Amano H, Tamaru Y, Kuramitsu K, Sakamoto Y, Monden M and Takai Y:

Necl-5/Poliovirus receptor interacts in cis with integrin

alphaVbeta3 and regulates its clustering and focal complex

formation. J Biol Chem. 282:18481–18496. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Amano H, Ikeda W, Kawano S, Kajita M,

Tamaru Y, Inoue N, Minami Y, Yamada A and Takai Y: Interaction and

localization of necl-5 and PDGF receptor beta at the leading edges

of moving NIH3T3 cells: Implications for directional cell movement.

Genes Cells. 13:269–284. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Takahashi M, Rikitake Y, Nagamatsu Y, Hara

T, Ikeda W, Hirata Ki and Takai Y: Sequential activation of rap1

and rac1 small G proteins by PDGF locally at leading edges of

NIH3T3 cells. Genes Cells. 13:549–569. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Christofori G: Split personalities: The

agonistic antagonist sprouty. Nat Cell Biol. 5:377–379. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kim HJ and Bar-Sagi D: Modulation of

signalling by sprouty: A developing story. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

5:441–450. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Reich A, Sapir A and Shilo B: Sprouty is a

general inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling.

Development. 126:4139–4147. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zheng Q, Wang B, Gao J, Xin N, Wang W,

Song X, Shao Y and Zhao C: CD155 knockdown promotes apoptosis via

AKT/bcl-2/bax in colon cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 22:131–140.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Stanietsky N, Simic H, Arapovic J, Toporik

A, Levy O, Novik A, Levine Z, Beiman M, Dassa L, Achdout H, et al:

The interaction of TIGIT with PVR and PVRL2 inhibits human NK cell

cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:17858–17863. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Johnston RJ, Comps-Agrar L, Hackney J, Yu

X, Huseni M, Yang Y, Park S, Javinal V, Chiu H, Irving B, et al:

The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T

cell effector function. Cancer Cell. 26:923–937. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Kong Y, Zhu L, Schell TD, Zhang J, Claxton

DF, Ehmann WC, Rybka WB, George MR, Zeng H and Zheng H: T-Cell

immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) associates with

CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and poor clinical outcome in AML

patients. Clin Cancer Res. 22:3057–3066. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Chauvin JM, Pagliano O, Fourcade J, Sun Z,

Wang H, Sander C, Kirkwood JM, Chen Th, Maurer M, Korman AJ and

Zarour HM: TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific

CD8+ T cells in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest.

125:2046–2058. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Guillerey C, Harjunpää H, Carrié N, Kassem

S, Teo T, Miles K, Krumeich S, Weulersse M, Cuisinier M and

Stannard K: TIGIT immune checkpoint blockade restores

CD8+ T-cell immunity against multiple myeloma. Blood.

132:1689–1694. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Lee WJ, Lee YJ, Choi ME, Yun KA, Won CH,

Lee MW, Choi JH and Chang SE: Expression of lymphocyte-activating

gene 3 and T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM

domains in cutaneous melanoma and their correlation with programmed

cell death 1 expression in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Am

Acad Dermatol. 81:219–227. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

O'Brien SM, Klampatsa A, Thompson JC,

Martinez MC, Hwang WT, Rao AS, Standalick JE, Kim S, Cantu E,

Litzky LA, et al: Function of human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res.

7:896–909. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

He W, Zhang H, Han F, Chen X, Lin R, Wang

W, Qiu H, Zhuang Z, Liao Q, Zhang W, et al: CD155T/TIGIT signaling

regulates CD8+ T-cell metabolism and promotes tumor

progression in human gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 77:6375–6388.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Zhang C, Wang Y, Xun X, Wang S, Xiang X,

Hu S, Cheng Q, Guo J, Li Z and Zhu J: TIGIT can exert

immunosuppressive effects on CD8+ T cells by the

CD155/TIGIT signaling pathway for hepatocellular carcinoma in

vitro. J Immunother. 43:236–243. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kurtulus S, Sakuishi K, Ngiow SF, Joller

N, Tan DJ, Teng MW, Smyth MJ, Kuchroo VK and Anderson AC: TIGIT

predominantly regulates the immune response via regulatory T cells.

J Clin Invest. 125:4053–4062. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Fourcade J, Sun Z, Chauvin JM, Ka M, Davar

D, Pagliano O, Wang H, Saada S, Menna C, Amin R, et al: CD226

opposes TIGIT to disrupt tregs in melanoma. JCI Insight.

26:e1211572018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Zhang Q, Bi J, Zheng X, Chen Y, Wang H, Wu

W, Wang Z, Wu Q, Peng H, Wei H, et al: Blockade of the checkpoint

receptor TIGIT prevents NK cell exhaustion and elicits potent

anti-tumor immunity. Nat Immunol. 19:723–732. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Stålhammar G, Seregard S and Grossniklaus

HE: Expression of immune checkpoint receptors Indoleamine

2,3-dioxygenase and T cell Ig and ITIM domain in metastatic versus

nonmetastatic choroidal melanoma. Cancer Med. 8:2784–2792.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Tang W, Pan X, Han D, Rong D, Zhang M,

Yang L, Ying J, Guan H, Chen Z and Wang X: Clinical significance of

CD8+ T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM

domains+ in locally advanced gastric cancer treated with

SOX regimen after D2 gastrectomy. Oncoimmunology. 8:e15938072019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Degos C, Heinemann M, Barrou J, Boucherit

N, Lambaudie E, Savina A, Gorvel L and Olive D: Endometrial tumor

microenvironment alters human NK cell recruitment, and resident NK

cell phenotype and function. Front Immunol. 10:8772019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zhang B, Zhao W, Li H, Chen Y, Tian H, Li

L, Zhang L, Gao C and Zheng J: Immunoreceptor TIGIT inhibits the

cytotoxicity of human cytokine-induced killer cells by interacting

with CD155. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 65:305–314. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Joller N, Hafler JP, Brynedal B, Kassam N,

Spoerl S, Levin SD, Sharpe AH and Kuchroo VK: Cutting edge: TIGIT

has T cell-intrinsic inhibitory functions. J Immunol.

186:1338–1342. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Joller N, Lozano E, Burkett PR, Patel B,

Xiao S, Zhu C, Xia J, Tan TG, Sefik E, Yajnik V, et al: Treg cells

expressing the coinhibitory molecule TIGIT selectively inhibit

proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cell responses. Immunity. 40:569–581.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lozano E, Dominguez-Villar M, Kuchroo V

and Hafler DA: The TIGIT/CD226 axis regulates human T cell

function. J Immunol. 188:3869–3875. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

De Vlaeminck Y, González-Rascón A,

Goyvaerts C and Breckpot K: Cancer-Associated myeloid regulatory

cells. Front Immunol. 7:1132016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Liu S, Zhang H, Li M, Hu D, Li C, Ge B,

Jin B and Fan Z: Recruitment of Grb2 and SHIP1 by the ITT-like

motif of TIGIT suppresses granule polarization and cytotoxicity of

NK cells. Cell Death Differ. 20:456–464. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Gao H, Sun Y, Wu Y, Luan B, Wang Y, Qu B

and Pei G: Identification of beta-arrestin2 as a G protein-coupled

receptor-stimulated regulator of NF-kappaB pathways. Mol Cell.

14:303–317. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Sun L, Deng L, Ea CK, Xia ZP and Chen ZJ:

The TRAF6 ubiquitin ligase and TAK1 kinase mediate IKK activation

by BCL10 and MALT1 in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell. 14:289–301. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Chen ZJ: Ubiquitination in signaling to

and activation of IKK. Immunol Rev. 246:95–106. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Asaoka Y, Ijichi H and Koike K: PD-1

blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med.

373:19792015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Josefsson SE, Beiske K, Blaker YN, Førsund

MS, Holte H, Østenstad B, Kimby E, Köksal H, Wälchli S, Bai B, et

al: TIGIT and PD-1 mark intratumoral T cells with reduced effector

function in B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Res.

7:355–362. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Hung AL, Maxwell R, Theodros D, Belcaid Z,

Mathios D, Luksik AS, Kim E, Wu A, Xia Y, Garzon-Muvdi T, et al:

TIGIT and PD-1 dual checkpoint blockade enhances antitumor immunity

and survival in GBM. Oncoimmunology. 7:e14667692018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zhang X, Zhang H, Chen L, Feng Z, Gao L

and Li Q: TIGIT expression is upregulated in T cells and causes T

cell dysfunction independent of PD-1 and Tim-3 in adult B lineage

acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell Immunol. 344:1039582019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Harjunpaa H and Guillerey C: TIGIT as an

emerging immune checkpoint. Clin Exp Immunol. 200:108–119. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Valsecchi ME: Combined nivolumab and

ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med.

373:12702015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|