Introduction

Nickel (Ni) compounds are classified as Group 1

carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Previous studies reported that workers processing and refining

sulfidic nickel ores have increased risk of pulmonary and sinonasal

cancers (1–6). Previously, special AT-rich

sequence-binding protein (SATB2), a nuclear matrix-associated

protein, was identified as the only common gene upregulated in

BEAS-2B cells transformed by nickel, arsenic, vanadate, and

hexavalent chromium (7). It is a

member of the family of special AT-rich sequence-binding proteins

and is an embryonic gene important in regulating stem cell

differentiation and development (8).

SATB2 overexpression has been observed in numerous cancers, such as

colon, breast, ovarian, lung, and sinonasal carcinomas (9–12). SATB2

has been increasingly studied in cancer development and is

considered to be a biomarker for colon cancer (9,13). SATB2

is upstream of numerous prognostic markers of colorectal cancer

(CRC) such as acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain 6 (ACSL6) and Vav

guanine nucleotide exchange factor 3 (VAV3) (14). Numerous downstream targets of SATB2

such as Bcl-2, Bsp, c-Myc, Klf4, Hoxa2 and Nanog are also important

regulators of cell pluripotency and survival (15). Thus, it is considered that

inappropriate induction of SATB2 in normal mammalian cells may act

as a driver of cell transformation.

In fact, the critical role of SATB2 in Ni-induced

BEAS-2B cell transformation has been identified (16) and in the present study the upstream

regulators for SATB2 signaling were investigated. Runt-related

transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) is a master regulator of

osteogenesis and it has a number of overlapping functions with

SATB2 (17,18). The interaction between RUNX2 and SATB2

in osteogenesis has been identified in several previous studies

(19–26). RUNX2 was detected in a limited number

of non-osseous tissues, while increased expression of RUNX2 has

been described in the progression and metastasis of several human

cancers. Overexpression of RUNX2 was observed in prostate,

pancreatic, breast, thyroid, and bone cancers (27–30).

Increased expression of RUNX2 suppressed microRNA (miRNA or miR)-31

allowing SATB2 protein translation and initiation of

carcinogenesis. Moreover, genes located downstream of RUNX2, such

as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), vascular epithelial growth

factor (VEGF), bone sialoprotein (BSP) and c-Myc were also involved

in promoting cancer cell metastasis (31–34). Genes

such as SRY-box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), snail family

transcriptional repressor 2 (SNAI2), snail family transcription

repression 3 (SNAI3), twist family bHLH transcription factor 1

(TWIST1) and SMAD family member 3 (SMAD3) regulated by RUNX2

induced cell invasion (35,36). RUNX2 modulated SATB2 expression by

suppressing the expression of miRNAs that directly target SATB2

mRNA in both osteogenesis and carcinogenesis (22,23,26,37–41).

Expression of RUNX2 appears to be a critical upstream event leading

to the increase of SATB2 and transforming BEAS-2B cells.

miRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that are known to

mediate mRNA degradation and inhibit translation of proteins as

well as altering chromatin structure during early development,

differentiation, metabolic control and cell death (42–45). The

expression of miRNAs has been revealed to be globally suppressed in

tumors (46). Several studies have

reported that altered miRNA expression is involved in various

stages of Ni carcinogenesis (47).

SATB2 has been revealed to be negatively regulated by several

miRNAs that target its 3′-untranslated region (UTR) during

osteogenesis and carcinogenesis, including miR-211, miR-31,

miR-23a/27a/24-2 cluster, miR-499, miR-34c, miR-875, miR-599

(10,23,37,38,40,48–54).

miR-31 was identified as a negative regulator for SATB2 in

arsenic-induced BEAS-2B transformation (40). In fact, miR-31 was also targeted by

RUNX2 and miR-31 allowed RUNX2 to regulate and increase SATB2

during osteogeneses (21,22). The aim of the study was to investigate

whether RUNX2 is an upstream regulator for SATB2, mediating

Ni-induced BEAS-2B cell transformation by regulating the expression

level of miR-31. This carcinogenic pathway mirrors what occurs

during normal bone development.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

BEAS-2B human bronchial epithelial cells were

obtained from the American Type Culture Collect (ATCC). Before the

start of the present study, the cells were examined at Genetica DNA

Laboratories and were revealed to be 100% authentic against a

reference BEAS-2B cell line (ATCC CRL-9609). Cells were cultured in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Atlanta Biologicals, Inc.; R&D Systems, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at

37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Ni-transformed (Ni-T) BEAS-2B cells were developed

by chronic exposure to 0.25 mM NiSO4 for 4 weeks

(7). Cells were seeded by single cell

suspension into soft agar and colonies were isolated and grown in

monolayer on culture dishes. Each clone was analyzed using

Affymetrix gene expression arrays and the clones with highest SATB2

expression were selected for the present study. The Ni-T cells were

maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% p/s at 37°C in

a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Stable overexpression and

knockdown

Stable overexpression of miR-31 in Ni-T cells was

achieved using miR-31 construct (cat. no. HmiR0138-MR04-10), which

was purchased from GeneCopoeia, Inc. RUNX2 plasmid constructs

(clone ID OHU22872D) were acquired from Genscript. Short hairpin

(sh)-RUNX2 (cat. no. HSH021333-CU6; scrambled control ID

CSHCTR001-1-CU6.1) and miR-31 inhibitor plasmid (cat. no.

HmiR-AN0401-AM01; control ID CmiR-AN0001-AM01) were obtained from

GeneCopoeia, Inc. The sequence for sh-RUNX2 and sh-miR-31 were as

follows: sh-RUNX2-a: 5′-GCAGCACGCTATTAAATCCAA-3′; sh-RUNX2-b:

5′-GCAGAATGGATGAATCTGTTT-3′; sh-RUNX2-c: GCGACCATATTGAAATTCCTC-3′;

scrambled control: 5′-GCTTCGCGCCGTAGTCTTA-3′; sh-miR-31:

5′-AGGCAAGAUGCUGGCAUAGCU-3′. Each plasmid was purified by a Qiagen

QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (cat. no. 27104) before transfection,

using the Lipofectamine™ LTX reagent with PLUS kit (cat. no.

15338030; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) used

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells

were plated in 2 ml growth medium in a 6-well plate and were

~70-80% confluent during transfection. For each transfection, 2.5

µg of purified plasmid was diluted in 250 µl Opti-MEM. Immediately

before transfection, 2.5 µl PLUS reagent was added to the diluted

plasmid. Then, 10 µl Lipofectamine™ LTX reagent was diluted in 250

µl Opti-MEM and then mixed with the plasmid and PLUS reagent. The

mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature before adding

into the well. The medium was replaced with fresh complete DMEM 24

h after transfection. The cells were divided onto 10 cm2

dishes 48 h after transfection and selection reagents (500 µg/ml

hygromycin or 0.5 µg/ml puromycin) were added. After selection for

2 weeks (hygromycin) or 3 days (puromycin), the pooled clones were

harvested for western blotting and RT-qPCR analysis.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR

Cells were lysed by TRI-reagent (Molecular Research

Center, Inc.) (1 ml/well of a 6-well plate). RNA was extracted

using 200 µl chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and centrifuged

at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, separating the RNA in the aqueous

phase. RNA was then precipitated by 500 µl isopropanol and washed

twice with 750 µl of 75% ethanol. RNA pellets were obtained by

centrifugation for 5 min at 13,000 × g at 4°C and air-dried for 10

min. RNA was solubilized in RNase-free water and heat-inactivated

at 65°C for 10 min.

Single-strand cDNA was generated from 250 ng RNA by

First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (cat. no. E6300; New England

Biolabs, Inc.) using random primers according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The primer and RNA mix were denatured at 70°C for 5

min. Reaction enzyme and buffer were mixed at a ratio of 1:5 and

added into each sample for cDNA synthesis. Samples were incubated

at 25°C for 5 min, followed by cDNA synthesis reaction at 42°C for

1 h and then the enzymes were inactivated at 80°C for 5 min.

Quantitative PCR analysis was performed by SYBR green qPCR Master

Mix (Roche Diagnostics). A total of 4 ng cDNA product and master

mix were added into each well of a 384-well plate. The reaction was

performed on an ABI PRISM 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and each sample was run in triplicate. The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 30

cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 10 min.

Relative gene expression level was quantified using the

2−ΔΔCq method (55) and

normalized to the expression of the house-keeping gene

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

miRNA extraction was performed according to the

manufacturer's instructions using the miRVana RNA isolation kit

(cat. no. AM1560, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

quantified by a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. cDNA was synthesized

using a TaqMan microRNA reverse transcription kit (cat. no.

4366596; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for miR-31, according to

the manufacturer's instructions. The relative expression level was

normalized to the expression of U6. Finally, qPCR analysis was

conducted by TaqMan primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on an

7900HT system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 40

cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Primers were designed

using the Primer Expression Software (v3.0.1; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and the sequences were as follows: RUNX2 forward,

5′-GAGTCCTTCTGTGGCATGCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGCCTGGTGGTGTCATTAG-3′;

SATB2 forward, 5′-TCTCCCCAAACACACCATCA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCAGCTCCTCGTCCTTATATTCA-3′; SIRT6 forward,

5′-TTTTTCTCTCGTGGTCTCACTTTGT-3′ and reverse,

5′-ACGGAGGGCAGGTGTAACC-3′; BSP forward, 5′-AAAGTGAGAACGGGGAACCTT-3′

and reverse, 5′-GATGCAAAGCCAGAATGGAT-3′; VEGF forward,

5′-CTTGCCTTGCTGCTCTAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGCTTGAAGATGTACTCG-3′;

GAPDH forward, 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGA-3′; miR-31 promoter A forward,

5′-TGCTATCTGCAGTACTGTGCTGAGG-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGAGAGGCTGTGGTTAGTTCCTGCT-3′; miR-31 promoter B forward,

5′-ACTGCCTTGACTTCCTGCCTTGGTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TAGCTAGGTCTGTACCCTGTCTCAG-3′.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed by heating in

boiling buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM sodium

orthovanadate). Samples were boiled at 100°C for 10 min and

sonicated on high for 15 min at 4°C. The cell debris was removed by

13,000 × g centrifugation for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant was

collected. The protein concentration was analyzed using the

Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). A total of 5

different dilutions of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) were prepared in boiling buffer to create the standard

curve. The absorbance was measured at 595 nm on spectrophotometer

SpectraMax M2 (Molecular Devices, LLC). Samples (30 µg each) were

mixed with a 6X SDS sample buffer (375 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 6% SDS,

4.8% glycerol, 9% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.03% bromophenol blue) and

separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were then transferred

onto a 0.45-µm nitrocellulose membrane at 100 V for 60 min. After

blocking with 5% skimmed milk in TBS for 30 min at room

temperature, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody in 5%

milk/TBS solution overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used

were: Anti-RUNX2 (1:200; product no. sc101145; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) anti-SATB2 (1:100; product no. ab51502; Abcam)

and anti-β-actin (1:1,000; product no. 3700S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.).

The membrane was washed with TBST (Tris-buffered

saline with 0.1% Tween-20 detergent) for 5 min 3 times before

horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody incubation

for 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibodies used were as

follows: HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (1:2,000 dilution; cat. no.

sc-516102; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.); or HPR-conjugated

anti-rabbit (1:2,000 dilution; cat. no. sc-2357; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). The protein bands were visualized by the

chemiluminescence after incubating the membrane in an

enhanced-chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for 2 min at room temperature and imaging films were

developed by an OPTIMAX X-Ray Film Processor (Merry X-Ray

Corporation). To control for sample loading and protein transfer,

β-actin was probed as an internal reference control. Quantification

of immunodetected protein bands was performed by ImageJ software

(V1.53e, National Institutes of Health).

Soft agar assay

Approximately 5,000 cells were mixed in a top layer

of 0.35% 2-hydroxyethylagarose (Type VII low gelling temperature;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)/DMEM upon a bottom layer of 0.5%

2-hydroxethylagarose/DMEM in a 6-well plate. A total of 200 cells

for each sample were seeded onto a 10 cm2 dish and

cultured for two weeks to assess plating efficiency. The colonies

in the plates were stained by 5% Giemsa solution (40% methanol/60%

glycerol) for ~4 h at room temperature (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and the number of colonies were determined. The cells in

agarose were humidified with 200 µl DMEM for each well twice a week

and cultured for four weeks until individual colonies were visible

under the light microscope at a magnification of ×20. Each well was

stained with 0.1% INT/BCIP solution (Roche Diagnostics) in 0.1 M

Tris/0.05 M MgCl2/0.1 M NaCl at 4°C overnight, and

images were captured by a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager Gel-Doc XR+

system and analyzed on the Image Lab software (v2.0.1 build 18;

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The number of colonies were counted by

ImageJ software using defined particle size of 6-infinity pixel

units and circularity of 0.30–1.00.

Scratch test

Cells were plated onto gridded plates (2×2 mm grids

on the bottom) (Nalge Nunc International). Upon reaching 90–100%

confluency, cells were washed with PBS twice and a single scratch

was produced across the monolayer between the grids by a 200-µl

pipette tip held perpendicular to the plate bottom. The plates were

gently washed with PBS to remove detached cells and cells were then

maintained in serum-free medium to inhibit proliferation that might

interfere with measurement of cell migration. For the CADD522

group, cells were cultured in medium containing 50 µM CADD522

during this experiment. CADD522 is a small molecule inhibitor for

RUNX2, and it was kindly provided by Dr. Antonino Passaniti from

University of Maryland School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD, USA).

Images were captured every 24 h after the scratch using a Nikon

digital DS-Fil1-U3 camera linked with a microscope by bright field

light at a magnification of ×20 and controlled by NIS-Elements F3.2

software on a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope (Nikon Corporation).

The wound healing rate was estimated by calculating the percentage

of the area of the wound covered or migrated during 48 h in the

image (wound area at 0 h-wound area at 48 h)/wound area at 0 h

×100%) measured by ImageJ software (v1.53e).

Invasion assay

The Matrigel-coated invasion chambers (Corning,

Inc.) were placed in a 24-well plate and balanced with low serum

medium (0.1% FBS/DMEM) at 37°C for 3 h. The medium was carefully

removed, and the lower wells were filled with 1 ml 10% FBS/DMEM.

Cells were washed with PBS twice and 5×104 cells were

suspended in 400 µl of 0.1% FBS/DMEM and seeded into each upper

chamber. For the CADD522 group, cells were pretreated with 50 µM

CADD522 for 24 h at 37°C and the medium in the chamber contained 50

µM CADD522. After culturing for 24 h, Transwell chambers were

washed with PBS and fixed by 10% formalin for 5 min and methanol

for 20 min at room temperature. The membranes in the bottom

chambers were stained with 10% Giemsa overnight at room temperature

and washed with H2O three times on the following day.

Non-invasive cells were inside of the chamber and were gently

removed by wet cotton swabs. The images were captured with a bright

field light microscope at a magnification of ×20 controlled by

NIS-Elements F3.2 software on a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope.

Three fields were randomly selected for each chamber membrane and

the number of invading cells were determined by ImageJ software

(v1.53e).

Cell viability and cytotoxicity

assay

Cell viability and cytotoxicity were assessed by the

CellTiter-Fluor Cell Viability Assay kit and CytoTox-Fluor

Cytotoxicity Assay kit (cat. nos. G6080 and G9260, respectively;

both from Promega Corporation) used according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate and then

treated with CADD522 at the indicated time-point and doses (25, 50,

100, 150 and 300 µg/ml for 48 h, respectively). Each treatment was

repeated 4 times. GF-AFC substrate and bis-AAF-R110 substrate were

diluted (200X) in the indicated assay buffers and mixed with

culture media at a ratio of 1:5. A total of 60 µl mixture was added

into each well. Plates were then incubated in the dark for 1 h at

room temperature. Cell viability was measured at

400Ex/505Em nm, and cell toxicity was

assessed at 485Ex/520Em nm on a fluorescence

plate.

RNA stability assay

Actinomycin D can form a stable complex with DNA and

block DNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity to inhibit new mRNA

synthesis, allowing measurements of mRNA decay (56). Briefly, approximately 1×105

cells were seeded on a 6-well plate. For the CADD522 treatment

group, cells were treated with CADD522 at 50 µg/ml for 24 h at 37°C

before collection. Cells were then treated with 10 µg/ml of

actinomycin D (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for

indicated time intervals (0, 8, 16 and 24 h) at 37°C. Cells were

then washed twice with PBS and collected by TRI-reagent and

subjected to RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis with random primers and

RT-qPCR analysis for SATB2 mRNA expression.

ChIP assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was used to

confirm the binding of RUNX2 in the promoter region of miR-31. Ni-T

cells were treated with 50 µM CADD522 for 48 h and were crosslinked

with 1% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in DMEM for 10 min

at room temperature. The crosslink reaction was stopped by treating

cells with 250 mM glycine for 5 min and were washed twice with cold

PBS supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors (1 tablet

in 10 ml buffer; cOmplete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor

cocktail; MilliporeSigma). The ChIP Assay kit (cat. no. 17-295;

MilliporeSigma) was used for immunoprecipitation of DNA-protein

complexes and reverse crosslinked DNA. Briefly, cells were

collected and suspended in SDS lysis buffer provided in the kit and

followed by sonication at 60 kHz to shear DNA between 200 and 1,000

base pairs. The chromatin size was verified on a 2% agarose gel.

Once the sonication conditions were optimized (36 cycles at 40%

power), samples were then diluted in ChIP dilution buffer. The

chromatin complex was then immunoprecipitated with anti-RUNX2

antibody (1:50; cat. no. ab236639; Abcam) or anti-IgG (1:50; cat.

no. 12-370; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) as a control overnight at

4°C. The following day, Protein A Agarose/Salmon Sperm DNA (50%

Slurry) was added at 4°C and incubated for 1 h. The beads were then

collected by centrifugation at 200 × g at 4°C for 1 min to remove

unbound non-specific DNA. The beads were washed in the following

order: Low salt, high salt, LiCl, and TE buffer. The RUNX2 protein

was then eluted from the antibody by elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1M

NaHCO3) and the protein-DNA crosslinks were reversed by heating at

65°C for 4 h. Samples were then treated with 10 µl of 0.5 M

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 20 µl of 1 M Tris-HCl, 2 µl

of 10 mg/ml Proteinase K, and 5 µl of 10 mg/ml RNase A and

incubated at 45°C for 1 h to digest proteins and RNAs. DNA was then

recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol

precipitation. To increase recovery of DNA, glycogen and sodium

acetate were added. DNA was eluted in TE buffer and the

concentration of DNA in the samples was analyzed by PicoGreen (cat.

no. P7589, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For qPCR

analysis, approximately 0.2 ng of DNA was used per well on 384-well

plates. The Ct values were determined using the percent input

method [100*2^ (Adjusted input-Ct (IP)] to calculate

enrichment.

Bioinformatics

To identify the target genes for miRNA or regulator

miRNAs for a particular gene, the potential interaction of the 3′

UTR of the genes with miRNAs was searched and confirmed by miRNA

target prediction databases TargetScanHuman v7.2 (www.targetscan.org). The promoter of miR-31 was

identified by searching the FANTOM5 data website (http://fantom.gsc.riken.jp), which is based on

prediction of the promoters of protein-coding genes, and the

specific promoter sequence upstream from the transcription start

site (TSS) of miR-31 host gene MIR31HG (RefSeq NR_027054) was

obtained at Ensembl website (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html).

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed at least three times

unless otherwise indicated and statistical significance of the

study was assessed using the mean ± standard deviation (SD) by the

two-tailed, unpaired t-test to compare the means of two groups or a

one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey's test for comparison of the means

of more than two groups using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad

Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Ni-T BEAS-2B cells exhibit enhanced

anchorage-independent growth, migration and invasion, as well as

increased SATB2 and RUNX2

Ni-induced cell transformation has been documented

in numerous cell studies (7,57–63). Ni-T

human lung epithelial cells were obtained following four weeks of

chronic exposure to 0.25 mM NiSO4 and isolated from

colonies that grew in soft agar (7).

As demonstrated in Fig. 1A and B,

Ni-T cells exhibited increased colony growth in agar compared with

normal BEAS-2B cells, indicating the acquisition of

anchorage-independent growth. Cellular anchorage-independent growth

in the soft agar matrix implies malignant transformation (64). Cell migration and invasion are key

processes for cancer metastasis and are also hallmarks of

malignancy (65). Cell migration

ability was determined by the scratch test. Cell invasion was

assessed by culturing cells in invasion chambers coated with

Matrigel matrix, which only allows cells with metastatic ability to

invade and transfer (66). As

revealed in Fig. 1C-F, Ni-T cells

demonstrated higher wound-healing capacity and increased cell

invasion compared with normal BEAS-2B cells.

In previous studies, SATB2 was indicated to be an

important mediator of Ni-induced cell transformation (7,16). It was

reported that knockdown of SATB2 in Ni-T cells reduced

anchorage-independent growth, cell migration, and tumor formation

in nude mice (16). SATB2 mRNA and

protein levels were significantly increased in Ni-T cells (Fig. 1G and H). To further study the

mechanisms of SATB2 induction, RUNX2 levels were measured, as the

latter is an upstream regulator for SATB2. RUNX2 was revealed as a

master regulator for osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells

(67). It is not commonly expressed

in normal mammalian cells, but it has been revealed to be increased

in numerous cancers (68). RUNX2

indirectly regulates SATB2 expression by inhibiting miRNAs in both

osteogenesis and cancers. The mRNA and protein levels of RUNX2 were

examined in Ni-T cells. As revealed in Fig. 1I and J, the expression of RUNX2 was

increased as compared with control BEAS-2B cells, indicating a

possible role of RUNX2 in Ni-mediated induction of SATB2.

Overexpression of RUNX2 promotes

cancer hallmarks in BEAS-2B cells

RUNX2 appears to be an upstream regulator of SATB2.

To investigate whether SATB2 can be induced by RUNX2 in BEAS-2B

cells, RUNX2 was stably overexpressed in BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 2A and B). The mRNA and protein levels

of SATB2 were increased by expressing RUNX2 (Fig. 2A and C). Overexpression of SATB2 in

BEAS-2B cells increased anchorage-independent growth (16). RUNX2 is an oncogene that plays an

important role in the progression and metastasis of several human

cancers (27–29,69).

Cancer hallmarks were examined in BEAS-2B cells stably expressing

RUNX2. To assess whether this was sufficient to promote

transformation, BEAS-2B cells overexpressing RUNX2 that were

cultured in soft agar demonstrated increased colony growth compared

with an empty vector control (Fig. 2D and

E). Overexpression of RUNX2 in BEAS-2B cells also promoted

acceleration of wound healing and cell invasion compared with an

empty vector control (Fig. 2F-I).

These findings indicated that RUNX2 induced cancer hallmarks in

BEAS-2B cells by inducing SATB2.

Inhibition of RUNX2 activity in

Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells eliminates cancer hallmarks

Previous studies have reported the role of RUNX2 in

lung cancer and inhibition of RUNX2 has been revealed to suppress

tumorigenesis in lung cancer cells (70–72). A

previous study using computer-assisted drug design (CADD) screening

detected a novel inhibitor of RUNX2 transcriptional activity termed

CADD522 (73–75). This inhibitor was used in Ni-T cells

to investigate whether inhibition of RUNX2 activity can suppress

cancer-related properties. Cell viability and cytotoxicity were

assessed by treating BEAS-2B cells for 24 h at 0–150 µM of CADD522.

There was no loss of cell viability or increased cytotoxicity at 50

µM of CADD522 for 24 h (Fig. 3A and

B). Since BEAS-2B cells tolerated a dose of 50 µM, this dose

was selected for further studies. To confirm that RUNX2 activity

can be suppressed by CADD522, Ni-T cells were treated with 50 µM

CADD522 for 24 h. RUNX2 mRNA and protein levels were not

significantly reduced in treated BEAS-2B or Ni-T cells (Fig. 3C and D). However downstream target

genes of RUNX2, VEGF and BSP were significantly inhibited by 50 µM

CADD522 treatment for 24 h in Ni-T cells (Fig. 3E-F). In addition, SIRT6 (sirtuin 6),

that was negatively regulated by RUNX2, was increased by CADD522

(Fig. 3G), indicating that CADD522

repressed RUNX2 trans-activity. SATB2 mRNA and protein were also

found reduced in Ni-T cells treated with 50 µM CADD522 (Fig. 3H and I).

| Figure 3.Inhibition of RUNX2 activity in Ni-T

BEAS-2B cells reverses cancer hallmarks. (A and B) Cell viability

and cytotoxicity assays in BEAS-2B cells treated with CADD522 for

24 h. (C and D) The expression levels of RUNX2 protein and mRNA in

CADD522-treated BEAS-2B cells and Ni-T cells by western blotting

and RT-qPCR assays. (E-G) The expression level of RUNX2 downstream

genes, VEGF, BSP, and SIRT6 mRNA in Ni-T cells treated with 50 µM

CADD522 by RT-qPCR. (H and I) The expression level of SATB2 protein

and mRNA in BEAS-2B cells and Ni-T cells treated with 50 µM CADD522

by western blotting and RT-qPCR assays. (J and K) Soft agar assay

of BEAS-2B cells and Ni-T cells treated with CADD522 at 50 µM and

compared with that treated with control. (L and M) The invasion of

BEAS-2B cells and Ni-T cells treated with CADD522 at 50 µM was

measured by Transwell assay and images were captured at a

magnification of ×20. (N and O) Cell migration ability in BEAS-2B

cells Ni-T cells with inhibited RUNX2 activity was measured by

scratch wound healing assays, and images were captured at a

magnification of ×20. Statistical significance was calculated by

the GraphPad Prism software using ANOVA for comparisons among

groups. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. RUNX2, runt-related

transcription factor 2; Ni-T, Ni-transformed; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; VEGF, vascular epithelial growth

factor; BSP, bone sialoprotein; SIRT6, sirtuin 6; SATB2, AT-rich

sequence-binding protein 2. |

The anchorage independent growth of cells was

analyzed by culturing Ni-T cells in soft agar containing 50 µM

CADD522 for 4 weeks. The colony number and size were significantly

reduced in CADD522-treated Ni-T cells compared with control

(Fig. 3J and K). The metastatic

potential of Ni-T treated with CADD522 was assessed in cell

invasion and migration assays. As revealed in Fig. 3L and M, CADD522-treated Ni-T cells

demonstrated reduced wound healing rate and invasion as compared

with the control.

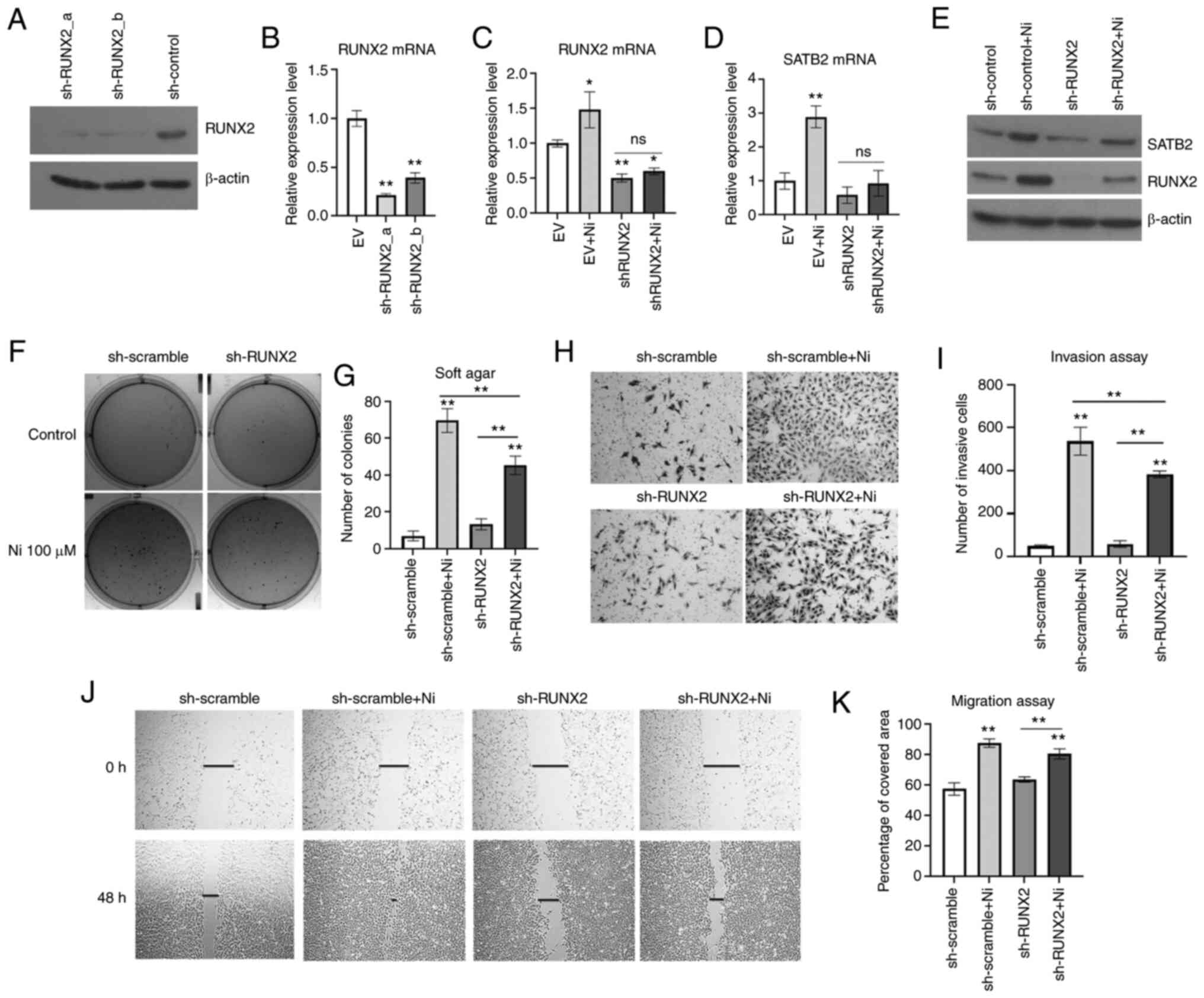

Knockdown of RUNX2 prevents Ni-induced

transformation in BEAS-2B cells

To further study the role of RUNX2 in Ni-induced

BEAS-2B transformation, RUNX2 was knocked down in normal BEAS-2B

cells by shRNA stable transfection prior to a chronic exposure to

Ni (Fig. 4A and B). NiCl2

and NiSO4 are two common soluble forms of Ni compounds

used in cell transformation studies (7,57–63). The RUNX2-knockdown cells experienced

massive cell death after treatment of 0.25 mM NiCl2 for

2 weeks. Thus, a lower dose and a longer treatment time were tried

with this compound. Cells were treated with 100 µM NiCl2

for 6 consecutive weeks to induce cell transformation. As

demonstrated in Fig. 4C-E, the

scramble control cells demonstrated significantly higher levels of

RUNX2 compared with shRUNX2-transfected cells. Chronic exposure to

Ni induced both RUNX2 and SATB2 level in control cells, while in

RUNX2-knockdown cells, Ni failed to increase the levels of RUNX2 or

SATB2 compared with controls. These results indicated that

inhibition of RUNX2 decreased the induction of SATB2 by Ni chronic

exposure.

Ni-induced cancer hallmarks were investigated in

BEAS-2B cells harboring knockdown of RUNX2. As revealed in Fig. 4F and G, Ni-treated BEAS-2B cells with

knockdown of RUNX2 demonstrated significantly reduced

anchorage-independent growth compared with the control. Although

knockdown of RUNX2 only slightly reduced cell migration of BEAS-2B

cells chronically treated with Ni (Fig.

4H and I), Ni-treated cells with knockdown of RUNX2

demonstrated a reduced invasiveness (Fig.

4J and K). These findings indicated that RUNX2 was essential in

maintaining the cancer hallmarks of Ni-T cells, which was likely

dependent on SATB2.

miR-31 connects RUNX2 and SATB2 in

Ni-induced cell transformation

SATB2 is maintained at low levels in most mature

organisms, and it is regulated by post-transcriptional

modifications and several miRNAs (48,76).

miR-31 is a negative regulator for SATB2 (22,38,40,41).

In a previous study, it was demonstrated that arsenic induced SATB2

level by inhibiting miR-31 in BEAS-2B cells (40). miR-31 could directly target SATB2 at

the 3′ UTR to diminish SATB2 mRNA stability and translation

(22,41). miR-31 has also been revealed to be

downstream of RUNX2 during osteogenic differentiation (22). It connects RUNX2 and SATB2 by acting

as a direct target of RUNX2 and an upregulator of SATB2 in

osteogenesis and carcinogenesis. A search of the promoter of miR-31

on Ensembl genome browser revealed a core binding sequence for

RUNX2 upstream of TSS of miR-31 (Fig.

5A). An illustration of RUNX2 binding at the miR-31 promoter

region and inhibiting its transcription is demonstrated in Fig. 5B. Furthermore, miR-31 complementary

base pairing was revealed with the sequence on SATB2 mRNA 3′ UTR

region to mediate its mRNA degradation and translation repression

and two target sites on 3′ UTR of SATB2 mRNA were identified by

TargetScan.

The expression level of miR-31 in Ni-T cells was

reduced compared with normal BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 5C). To confirm whether miR-31 was

regulated by RUNX2, BEAS-2B cells overexpressing RUNX2 and

CADD522-treated Ni-T cells were subjected to miRNA extraction and

qPCR analysis for the expression level of miR-31. Overexpression of

RUNX2 in BEAS-2B cells reduced the expression level miR-31 compared

with the vector control (Fig. 5D),

while increased miR-31 expression levels were observed in Ni-T

cells and BEAS-2B cells with inhibited RUNX2 activity (Fig. 5E). The physical binding of RUNX2 to

the core binding site on miR-31 promoter was demonstrated by Deng

et al (22). To further

investigate the mechanism by which CADD522 induced the expression

level of miR-31, the binding of RUNX2 at the core binding site of

miR-31 promotor region was examined by ChIP in Ni-T cells. A primer

that spans the binding site in the promoter of miR-31 was used for

qPCR analysis and another primer spanning an unrelated promoter

region was used as a negative control. The binding of RUNX2 to

miR-31 promoter was confirmed. Upon treatment with CADD522, the

binding of RUNX2 was slightly reduced as compared with control

(Fig. 5F), indicating that CADD522

alleviated the inhibitory effect by RUNX2 on miR-31 promoter and

thereby increased the expression level of miR-31.

It is known that miRNAs target downstream mRNAs by

promoting mRNA degradation and reducing translation (77). Since CADD52 induced expression of

miR-31, an inhibition of DNA transcription by actinomycin D in

CADD522-treated Ni-T cells was conducted to assess the stability of

SATB2 mRNA. CADD522-treated Ni-T cells had less SATB2 mRNA

stability compared with the control (Fig.

5G), indicating that increased SATB2 mRNA degradation was the

operative event. These findings indicated that RUNX2 increased

SATB2 by suppressing the expression of miR-31, since RUNX2 directly

targeted miR-31 promoter to negatively regulate its expression, and

miR-31 was hypothesized to contribute to decreased stability of

SATB2 mRNA in Ni-T cells.

Overexpression of miR-31 represses

Ni-induced cancer hallmarks

miRNAs target downstream mRNAs by base-paring with a

complementary sequence on their 3′ UTR, while the levels of target

mRNAs are not necessarily affected by miRNAs. Genes not affected by

the binding of targeting miRNAs are termed tuning genes, and those

that can be turned off by the binding of miRNAs are termed switch

genes (44,78). To investigate whether miR-31 regulates

the level of SATB2 in Ni-T cells, miR-31 was ectopically expressed

(Fig. 6A). SATB2 protein and mRNA

expression levels were measured by western blotting and qPCR. As

revealed in Fig. 6B and C,

ectopically expressed miR-31 in Ni-T cells suppressed the protein

and mRNA levels of SATB2. However, unlike CADD522 which promoted

SATB2 mRNA degradation, the stability of SATB2 mRNA was not

significantly impaired in miR-31 overexpressed cells compared with

vector control (Fig. 6D). This may be

due to suppressed transcription of miR-31 under the treatment of

actinomycin D, failing to show the direct link between miR-31 and

SATB2.

Since exogenous expression of miR-31 in Ni-T cells

reduced SATB2 levels, and knockdown of SATB2 was revealed to reduce

cell transformation (16), it was

hypothesized that cell transformation and metastasis would also be

inhibited in Ni-T cells stably expressing exogenous miR-31. The

colony number and size in soft agar were significantly decreased in

miR-31-overexpressing cells compared with the vector control as

demonstrated in Fig. 6E and F. To

investigate whether the expression of miR-31 in Ni-T cells also

suppressed cellular metastasis, both migration and invasion were

analyzed using the scratch test and invasion assay, respectively.

As demonstrated in Fig. 6G and H, the

wound healing rate was reduced in Ni-T cells ectopically expressing

miR-31 compared with the control, indicating a decreased cell

migration ability. The number of invasive cells was also

significantly reduced in miR-31-overexpressed cells (Fig. 6I and J). Collectively, overexpression

of miR-31 reduced cell transformation and metastatic potential in

Ni-T cells, indicating that miR-31 could be a critical regulator in

Ni-induced cell transformation by its effects on SATB2

expression.

Inhibition of miR-31 increases cancer

hallmarks in BEAS-2B cells

To further examine the role of miR-31 in cell

transformation, miR-31 was knocked down in BEAS-2B cells by shRNA

(Fig. 7A). The mRNA and protein

levels of SATB2 were increased in one of the clones of

miR-31-knockdown BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 7B

and C). Inhibition of miR-31 level in BEAS-2B cells

significantly promoted anchorage-independent growth as compared

with the scramble shRNA-transfected controls (Fig. 7D and E). The cell metastasis was

investigated in BEAS-2B cells with knockdown of miR-31. Cells with

reduced expression of miR-31 exhibited increased migration compared

with the scramble shRNA control (Fig. 7F

and G). Furthermore, knockdown of miR-31 effectively increased

the invasiveness as compared with the control (Fig. 7H and I). Collectively, these results

indicated that miR-31 played an important role in inhibiting cell

transformation and metastasis in BEAS-2B cells.

Discussion

The present study proposed a signaling pathway,

RUNX2/miR-31/SATB2, that drives Ni-induced BEAS-2B cell

transformation. Expression of SATB2 and RUNX2 were both increased

in Ni-transformed BEAS-2B cells (Ni-T) and miR-31 levels were

reduced. Ectopic expression of RUNX2 in BEAS-2B cells promoted

cancer hallmarks, while an inhibition of RUNX2 in Ni-T cells or

knockdown of RUNX2 in BEAS-2B cells prior to Ni treatment

significantly prevented the induction of SATB2 as well as

carcinogenesis. These results indicated an important role of RUNX2

in Ni-induced cell transformation, which is likely mediated by

inducing the expression of SATB2. miR-31 was demonstrated to be an

upstream negative regulator of SATB2 in arsenic-transformed BEAS-2B

cells (40). miR-31 is targeted by

RUNX2 at the promoter and its expression level was revealed to be

regulated by RUNX2 in BEAS-2B cells. Knockdown of miR-31 in normal

BEAS-2B cells increased SATB2 level and cancer hallmarks, while

overexpression of miR-31 in Ni-T cells reversed transformation by

decreasing SATB2. Different doses and treatment times for soluble

Ni-induced cell transformation have been reported in numerous

studies (7,57–63),

however a dose-response effect of soluble Ni on cell growth,

migration and invasion has not been well explored in the same

detail and could be studied in the future. Furthermore, a

dose-response relationship between soluble Ni exposure and

expression levels of these components will be explored in future

studies. Collectively, these results indicated that long-term

soluble NiSO4 exposure induced SATB2 expression through

the induction of RUNX2 and inhibition of miR-31 which is a

mechanism for Ni-induced BEAS-2B cell transformation.

Ni-induced cell transformation occurs through

several mechanisms, including the hypoxia-inducible signaling

pathway, epigenetic changes including DNA methylation, histone

acetylation and miRNA regulation, tumor suppressor gene loss and

oncogene activation (79).

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a heterodimeric transcriptional

factor that consists of 2 subunits, HIF-1α and HIF-1β, both of

which are required for HIF-1 to function; HIF-1β is integral in

HIF-1 heterodimer formation, while HIF-1α is the key regulatory

subunit and is responsible for HIF-1 transcriptional activity

(80). Previous studies demonstrated

that Ni could replace iron in the HIF prolyl hydroxylases and thus

inhibit the association of HIF-1α with Von-Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3

ubiquitin ligase, which in turn stabilizes HIF protein (81–83). RUNX2

was also revealed to cause accumulation of HIF-1α protein in

chondrocytes since it stabilizes HIF-1α by competition with pVHL at

the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) of HIF-1α and

prevents HIF-1α ubiquitination (84).

Another study confirmed the physical binding of the Runt domain of

RUNX2 with HIF-1α and indicated that RUNX2 and HIF-1α interaction

induced the expression of the downstream gene vascular epithelial

growth factor (VAGF) (85). Recently

SATB2 was also revealed to regulate HIF-1a expression under hypoxia

signaling and mediate cell stemness, proliferation and cell

survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma (86). These findings indicated that both

RUNX2 and SATB2 may also be involved in the mechanism of the

Ni-induced hypoxia signaling pathway.

Carcinogenic mechanisms induced by Ni can ultimately

lead to the activation of proto-oncogenes or inactivation of tumor

suppressor genes such as p53 (87–89). SATB2

was reported to be an oncogene in numerous cancers (48). SATB2 was indicated as a diagnostic

marker for CRC since SATB2 stained positively in 71–97% of primary

and metastatic CRC biopsies (90). A

reduced expression level of SATB2 in colon cancer was associated

with poor prognosis, while increased SATB2 expression enhanced

therapeutic sensitivity (90–94). A previous study demonstrated that

SATB2 induction and subsequent transformation of colon epithelial

cells (CRL-1831) was mediated through Wnt/β-catenin/T-cell factor

(TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) pathway (13). Numerous downstream genes of the

pathway have been associated with carcinogenesis, including c-Myc

and VEGF (95). In fact, these genes

are also downstream of RUNX2 (96,97). RUNX2

has been linked with SATB2 by numerous osteo-specific markers and

miRNAs during bone development and carcinogenesis (19,20,22–25,39).

RUNX2 was indicated to be a novel prognostic marker

in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) since its expression was

revealed to be tightly related with tumor size, stage, and lymph

node metastasis (72). The present

study focused on the role of RUNX2 in Ni-T cells and confirmed that

RUNX2 is an upstream regulator of SATB2, and it is important in

mediating cell transformation induced by Ni. Inhibition of RUNX2

was achieved by two methods in the present study, a small molecule

inhibitor and gene knockdown. The advantage of small molecule drugs

is functioning rapidly, continuously, and often reversibly across

cell types and species (98) From a

clinical point of view, it has the potential for therapeutic

development, and the results of the present study could possibly

add meaning to it. A concern in the use of small molecule

inhibitors of RUNX2 would be its off-target effects. A previous

study has demonstrated that CADD522 is specific for the RUNX family

and highly specific in targeting RUNX2 transcriptional activity

(75). Stable knockdown of RUNX2 by

shRNA in normal BEAS-2B cells was carried out to provide further

evidence that RUNX2 is critical in maintaining cancer hallmarks

during Ni-induced transformation. Although SATB2 is considered a

tumor suppressor for NSCLC (99),

SATB2 levels increased in Ni-T BEAS-2B cells. In addition,

inhibition of the expression level of SATB2 in Ni-T cells reduced

cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth (100). SATB2 was also induced by arsenic in

BEAS-2B transformed cells, and this induction was demonstrated to

be achieved by downregulated miR-31, which was required to induce

malignant transformation of BEAS-2B cells (40).

RUNX2 acts as an upstream regulator of miR-31 by

directly targeting its promoter region in bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells (22). The expression

level of miR-31 was negatively regulated by RUNX2 following

Ni-transformation, and the binding of RUNX2 at miR-31 promoter was

demonstrated. miR-31 is a negative regulator of SATB2 since

overexpression of miR-31 suppressed SATB2 level in Ni-T cells,

while inhibition of miR-31 restored SATB2 to normal low levels.

miRNAs function by binding to the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs and

subsequently mediate mRNA de-capping, triggering degradation, as

well as reducing mRNA translation (101). SATB2 mRNA was directly targeted by

miR-31 in CRC and breast cancer cells (38,53). In

the present study, it was observed that miR-31 affected SATB2

levels, and further studies on the mechanism by which miR-31

regulates SATB2 in this pathway are required.

Two target sequences that miR-31 bind to the 3′ UTR

of SATB2 mRNA were identified. Inhibition of RUNX2 transcriptional

activity by CADD522 increased miR-31 levels, reducing the half-life

of SATB2 mRNA, indicating that miR-31 promoted SATB2 mRNA

degradation. miR-31 is a highly evolutionarily conserved miRNA and

its expression was revealed to be disrupted in the progression of

numerous cancers and diseases such as psoriasis and systemic lupus

erythematosus (102). The

transcriptional regulation of miR-31 is suppressed in breast,

prostate, liver, leukemia, and melanoma cancers, and this is partly

mediated by hypermethylation of a CpG island in miR-31 promoter

(103–107). In fact, DNA methylation is the most

prevalent epigenetic event in Ni-induced lung cancer (81,108–112).

Ni elicited global hypermethylation and suppressed key tumor

suppressor genes to induce senescence as part of its carcinogenic

pathway (113). Ni was also revealed

to alter the expression levels of numerous ncRNAs by regulating the

activity of DNA methyltransferases (DMNTs) (47). The level of miR-31 was reduced in Ni-T

cells, allowing SATB2 protein to be expressed. In addition,

RUNX2/miR-31 may not be the only upstream signaling for

SATB2-mediated carcinogenesis induced by Ni since RUNX2 and SATB2

are regulated by other miRNAs such as miR-23a/27a/24-2 in cancer

cells (23).

The present study described a signaling pathway

leading to increased SATB2 in Ni-induced BEAS-2B transformation. It

demonstrated that induced expression of RUNX2 by Ni-suppressed

miR-31 expression by silencing its promoter, thereby allowing SATB2

mRNA translation, and increasing the protein level of SATB2,

leading to cell transformation. Since SATB2 is a common gene

significantly induced by different heavy metals in BEAS-2B cells

(7), it would be of interest to

investigate whether this is a shared pathway for other

metal-induced lung carcinogenesis in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Institutes of Health grants (grant nos. ES000260, ES023174,

ES029359, ES030583 CA229234 and ES026138).

Availability of data and materials

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study

are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Author's contributions

MC, YZ and AJ contributed to the conception and

design of the study. AJ performed preliminary experiments to

establish the methodology to assess RUNX2 and miR-31 expression in

cells. QYC generated miR-31 overexpression and knockdown clones,

confirmed that these clones had authentic overexpression and

knockdown and conducted cell transformation assays for these

clones. YZ performed all of the remaining experiments that are

reported in the study. YZ, QYC and NR analyzed the data and

produced the final images of the study using the software mentioned

in the study. HS and NR provided technical support and data

interpretation for the study. YZ prepared the first draft of the

manuscript. YZ and MC revised the manuscript according to the

comments from the reviewers and editors. HS also assisted in

confirming and providing detailed methods of the study. MC

supervised the preparation of the manuscript and was the PI on NIH

grants that financially supported this publication. All authors

have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Huvinen M and Pukkala E: Cancer incidence

among Finnish ferrochromium and stainless steel production workers

in 1967–2011: A cohort study. BMJ Open. 3:e0038192013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Grimsrud TK and Andersen A: Evidence of

carcinogenicity in humans of water-soluble nickel salts. J Occup

Med Toxicol. 5:72010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Andersen A, Berge SR, Engeland A and

Norseth T: Exposure to nickel compounds and smoking in relation to

incidence of lung and nasal cancer among nickel refinery workers.

Occup Environ Med. 53:708–713. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Seilkop SK and Oller AR: Respiratory

cancer risks associated with low-level nickel exposure: An

integrated assessment based on animal, epidemiological, and

mechanistic data. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 37:173–190. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Anttila A, Pukkala E, Aitio A, Rantanen T

and Karjalainen S: Update of cancer incidence among workers at a

copper/nickel smelter and nickel refinery. Int Arch Occup Environ

Health. 71:245–250. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Moulin JJ, Clavel T, Roy D, Dananche B,

Marquis N, Fevotte J and Fontana JM: Risk of lung cancer in workers

producing stainless steel and metallic alloys. Int Arch Occup

Environ Health. 73:171–180. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Clancy HA, Sun H, Passantino L, Kluz T,

Munoz A, Zavadil J and Costa M: Gene expression changes in human

lung cells exposed to arsenic, chromium, nickel or vanadium

indicate the first steps in cancer. Metallomics. 4:784–793. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Savarese F, Davila A, Nechanitzky R, De La

Rosa-Velazquez I, Pereira CF, Engelke R, Takahashi K, Jenuwein T,

Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Fisher AG and Grosschedl R: Satb1 and Satb2

regulate embryonic stem cell differentiation and Nanog expression.

Genes Dev. 23:2625–2638. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Magnusson K, de Wit M, Brennan DJ, Johnson

LB, McGee SF, Lundberg E, Naicker K, Klinger R, Kampf C, Asplund A,

et al: SATB2 in combination with cytokeratin 20 identifies over 95%

of all colorectal carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 35:937–948. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jiang G, Cui Y, Yu X, Wu Z, Ding G and Cao

L: miR-211 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma by downregulating

SATB2. Oncotarget. 6:9457–9466. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cartularo L, Kluz T, Cohen L, Shen SS and

Costa M: Molecular mechanisms of malignant transformation by low

dose cadmium in normal human bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One.

11:e01550022016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fukuhara M, Agnarsdottir M, Edqvist PH,

Coter A and Ponten F: SATB2 is expressed in Merkel cell carcinoma.

Arch Dermatol Res. 308:449–454. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yu W, Ma Y, Shankar S and Srivastava RK:

SATB2/β-catenin/TCF-LEF pathway induces cellular transformation by

generating cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep.

7:109392017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bae T, Rho K, Choi JW, Horimoto K, Kim W

and Kim S: Identification of upstream regulators for prognostic

expression signature genes in colorectal cancer. BMC Syst Biol.

7:862013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yu W, Ma Y, Shankar S and Srivastava RK:

Role of SATB2 in human pancreatic cancer: Implications in

transformation and a promising biomarker. Oncotarget.

7:57783–57797. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wu F, Jordan A, Kluz T, Shen S, Sun H,

Cartularo LA and Costa M: SATB2 expression increased

anchorage-independent growth and cell migration in human bronchial

epithelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 293:30–36. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhao X, Qu Z, Tickner J, Xu J, Dai K and

Zhang X: The role of SATB2 in skeletogenesis and human disease.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 25:35–44. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Komori T: Regulation of skeletal

development by the Runx family of transcription factors. J Cell

Biochem. 95:445–453. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z,

Deng JM, Behringer RR and de Crombrugghe B: The novel zinc

finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for

osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 108:17–29.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tang W, Li Y, Osimiri L and Zhang C:

Osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osterix (Osx) is an

upstream regulator of Satb2 during bone formation. J Biol Chem.

286:32995–33002. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yu L, Xu Y, Qu H, Yu Y, Li W, Zhao Y and

Qiu G: Decrease of miR-31 induced by TNF-α inhibitor activates

SATB2/RUNX2 pathway and promotes osteogenic differentiation in

ethanol-induced osteonecrosis. J Cell Physiol. 234:4314–4326. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Deng Y, Wu S, Zhou H, Bi X, Wang Y, Hu Y,

Gu P and Fan X: Effects of a miR-31, Runx2, and Satb2 regulatory

loop on the osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem

cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22:2278–2286. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hassan MQ, Gordon JA, Beloti MM, Croce CM,

van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS and Lian JB: A network connecting

Runx2, SATB2, and the miR-23a~27a~24-2 cluster regulates the

osteoblast differentiation program. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

107:19879–19884. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dobreva G, Chahrour M, Dautzenberg M,

Chirivella L, Kanzler B, Farinas I, Karsenty G and Grosschedl R:

SATB2 is a multifunctional determinant of craniofacial patterning

and osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 125:971–986. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dowrey T, Schwager EE, Duong J, Merkuri F,

Zarate YA and Fish JL: Satb2 regulates proliferation and nuclear

integrity of pre-osteoblasts. Bone. 127:488–498. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang J, Tu Q, Grosschedl R, Kim MS,

Griffin T, Drissi H, Yang P and Chen J: Roles of SATB2 in

osteogenic differentiation and bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part

A. 17:1767–1776. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kayed H, Jiang X, Keleg S, Jesnowski R,

Giese T, Berger MR, Esposito I, Lohr M, Friess H and Kleeff J:

Regulation and functional role of the Runt-related transcription

factor-2 in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 97:1106–1115. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pratap J, Lian JB, Javed A, Barnes GL, van

Wijnen AJ, Stein JL and Stein GS: Regulatory roles of Runx2 in

metastatic tumor and cancer cell interactions with bone. Cancer

Metastasis Rev. 25:589–600. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Niu DF, Kondo T, Nakazawa T, Oishi N,

Kawasaki T, Mochizuki K, Yamane T and Katoh R: Transcription factor

Runx2 is a regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

invasion in thyroid carcinomas. Lab Invest. 92:1181–1190. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Thomas DM, Johnson SA, Sims NA, Trivett

MK, Slavin JL, Rubin BP, Waring P, McArthur GA, Walkley CR,

Holloway AJ, et al: Terminal osteoblast differentiation, mediated

by runx2 and p27KIP1, is disrupted in osteosarcoma. J Cell Biol.

167:925–934. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Akech J, Wixted JJ, Bedard K, van der Deen

M, Hussain S, Guise TA, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Languino LR,

Altieri DC, et al: Runx2 association with progression of prostate

cancer in patients: Mechanisms mediating bone osteolysis and

osteoblastic metastatic lesions. Oncogene. 29:811–821. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Sun X, Wei L, Chen Q and Terek RM: HDAC4

represses vascular endothelial growth factor expression in

chondrosarcoma by modulating RUNX2 activity. J Biol Chem.

284:21881–21890. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Papachristou DJ, Papachristou GI,

Papaefthimiou OA, Agnantis NJ, Basdra EK and Papavassiliou AG: The

MAPK-AP-1/-Runx2 signalling axes are implicated in chondrosarcoma

pathobiology either independently or via up-regulation of VEGF.

Histopathology. 47:565–574. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Inman CK and Shore P: The osteoblast

transcription factor Runx2 is expressed in mammary epithelial cells

and mediates osteopontin expression. J Biol Chem. 278:48684–48689.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Baniwal SK, Khalid O, Gabet Y, Shah RR,

Purcell DJ, Mav D, Kohn-Gabet AE, Shi Y, Coetzee GA and Frenkel B:

Runx2 transcriptome of prostate cancer cells: Insights into

invasiveness and bone metastasis. Mol Cancer. 9:2582010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yuen HF, Kwok WK, Chan KK, Chua CW, Chan

YP, Chu YY, Wong YC, Wang X and Chan KW: TWIST modulates prostate

cancer cell-mediated bone cell activity and is upregulated by

osteogenic induction. Carcinogenesis. 29:1509–1518. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Aprelikova O, Yu X, Palla J, Wei BR, John

S, Yi M, Stephens R, Simpson RM, Risinger JI, Jazaeri A and

Niederhuber J: The role of miR-31 and its target gene SATB2 in

cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 9:4387–4398. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang MH, Yu J, Chen N, Wang XY, Liu XY,

Wang S and Ding YQ: Elevated microRNA-31 expression regulates

colorectal cancer progression by repressing its target gene SATB2.

PLoS One. 8:e853532013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang Y, Xie RL, Croce CM, Stein JL, Lian

JB, van Wijnen AJ and Stein GS: A program of microRNAs controls

osteogenic lineage progression by targeting transcription factor

Runx2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:9863–9868. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen QY, Li J, Sun H, Wu F, Zhu Y, Kluz T,

Jordan A, DesMarais T, Zhang X, Murphy A and Costa M: Role of

miR-31 and SATB2 in arsenic-induced malignant BEAS-2B cell

transformation. Mol Carcinog. 57:968–977. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ge J, Guo S, Fu Y, Zhou P, Zhang P, Du Y,

Li M, Cheng J and Jiang H: Dental follicle cells participate in

tooth eruption via the RUNX2-miR-31-SATB2 Loop. J Dent Res.

94:936–944. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li Z, Hassan MQ, Volinia S, van Wijnen AJ,

Stein JL, Croce CM, Lian JB and Stein GS: A microRNA signature for

a BMP2-induced osteoblast lineage commitment program. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 105:13906–13911. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li Z, Hassan MQ, Jafferji M, Aqeilan RI,

Garzon R, Croce CM, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS and Lian JB:

Biological functions of miR-29b contribute to positive regulation

of osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 284:15676–15684. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Genomics,

biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 116:281–297. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pawlicki JM and Steitz JA: Nuclear

networking fashions pre-messenger RNA and primary microRNA

transcripts for function. Trends Cell Biol. 20:52–61. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra

E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA,

et al: MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature.

435:834–838. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhu Y, Chen QY, Li AH and Costa M: The

role of non-coding RNAs involved in nickel-induced lung

carcinogenic mechanisms. Inorganics. 7:812019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Chen QY, Des Marais T and Costa M:

Deregulation of SATB2 in carcinogenesis with emphasis on

miRNA-mediated control. Carcinogenesis. 40:393–402. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Tian W, Wang G, Liu Y, Huang Z, Zhang C,

Ning K, Yu C, Shen Y, Wang M, Li Y, et al: The miR-599 promotes

non-small cell lung cancer cell invasion via SATB2. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 485:35–40. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

El Bezawy R, Cominetti D, Fenderico N,

Zuco V, Beretta GL, Dugo M, Arrighetti N, Stucchi C, Rancati T,

Valdagni R, et al: miR-875-5p counteracts epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition and enhances radiation response in prostate cancer

through repression of the EGFR-ZEB1 axis. Cancer Lett. 395:53–62.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gu J, Wang G, Liu H and Xiong C: SATB2

targeted by methylated miR-34c-5p suppresses proliferation and

metastasis attenuating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in

colorectal cancer. Cell Prolif. 51:e124552018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Sun X, Liu S, Chen P, Fu D, Hou Y, Hu J,

Liu Z, Jiang Y, Cao X, Cheng C, et al: miR-449a inhibits colorectal

cancer progression by targeting SATB2. Oncotarget. 8:100975–100988.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Luo LJ, Yang F, Ding JJ, Yan DL, Wang DD,

Yang SJ, Ding L, Li J, Chen D, Ma R, et al: miR-31 inhibits

migration and invasion by targeting SATB2 in triple negative breast

cancer. Gene. 594:47–58. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Gong Y, Xu F, Zhang L, Qian Y, Chen J,

Huang H and Yu Y: MicroRNA expression signature for Satb2-induced

osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow stromal cells. Mol Cell

Biochem. 387:227–239. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ratnadiwakara M and Änkö ML: mRNA

stability assay using transcription inhibition by actinomycin D in

mouse pluripotent stem cells. Bio-Protocol. 8:e30722018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Costa M: Molecular mechanisms of nickel

carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 31:321–337. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Chen QY and Costa M: A comprehensive

review of metal-induced cellular transformation studies. Toxicol

Appl Pharmacol. 331:33–40. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Huang H, Zhu J, Li Y, Zhang L, Gu J, Xie

Q, Jin H, Che X, Li J, Huang C, et al: Upregulation of SQSTM1/p62

contributes to nickel-induced malignant transformation of human

bronchial epithelial cells. Autophagy. 12:1687–1703. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Pang Y, Li W, Ma R, Ji W, Wang Q, Li D,

Xiao Y, Wei Q, Lai Y, Yang P, et al: Development of human cell

models for assessing the carcinogenic potential of chemicals.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 232:478–486. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Rani AS, Qu DQ, Sidhu MK, Panagakos F,

Shah V, Klein KM, Brown N, Pathak S and Kumar S: Transformation of

immortal, non-tumorigenic osteoblast-like human osteosarcoma cells

to the tumorigenic phenotype by nickel sulfate. Carcinogenesis.

14:947–953. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang L, Fan J, Hitron JA, Son YO, Wise JT,

Roy RV, Kim D, Dai J, Pratheeshkumar P, Zhang Z and Shi X: Cancer

stem-like cells accumulated in nickel-induced malignant

transformation. Toxicol Sci. 151:376–387. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang Q, Salnikow K, Kluz T, Chen LC, Su

WC and Costa M: Inhibition and reversal of nickel-induced

transformation by the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 192:201–211. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Borowicz S, Van Scoyk M, Avasarala S,

Karuppusamy Rathinam MK, Tauler J, Bikkavilli RK and Winn RA: The

soft agar colony formation assay. J Vis Exp. e519982014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Jiang WG, Sanders AJ, Katoh M, Ungefroren

H, Gieseler F, Prince M, Thompson SK, Zollo M, Spano D, Dhawan P,

et al: Tissue invasion and metastasis: Molecular, biological and

clinical perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol. 35 Suppl:S244–S275. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sahai E: Mechanisms of cancer cell

invasion. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 15:87–96. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A,

Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, et al:

Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone

formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell.

89:755–764. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Valenti MT, Serafini P, Innamorati G, Gili

A, Cheri S, Bassi C and Dalle Carbonare L: Runx2 expression: A

mesenchymal stem marker for cancer. Oncol Lett. 12:4167–4172. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Thomas DM, Carty SA, Piscopo DM, Lee JS,

Wang WF, Forrester WC and Hinds PW: The retinoblastoma protein acts

as a transcriptional coactivator required for osteogenic

differentiation. Mol Cell. 8:303–316. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Bai X, Meng L, Sun H, Li Z, Zhang X and

Hua S: MicroRNA-196b Inhibits cell growth and metastasis of lung

cancer cells by targeting Runx2. Cell Physiol Biochem. 43:757–767.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Herreno AM, Ramirez AC, Chaparro VP,

Fernandez MJ, Canas A, Morantes CF, Moreno OM, Bruges RE, Mejia JA,

Bustos FJ, et al: Role of RUNX2 transcription factor in epithelial

mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer lung cancer:

Epigenetic control of the RUNX2 P1 promoter. Tumour Biol.

41:10104283198510142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Li H, Zhou RJ, Zhang GQ and Xu JP:

Clinical significance of RUNX2 expression in patients with nonsmall

cell lung cancer: A 5-year follow-up study. Tumour Biol.

34:1807–1812. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Underwood KF, D'Souza DR, Mochin-Peters M,

Pierce AD, Kommineni S, Choe M, Bennett J, Gnatt A, Habtemariam B,

MacKerell AD Jr and Passaniti A: Regulation of RUNX2 transcription

factor-DNA interactions and cell proliferation by vitamin D3

(cholecalciferol) prohormone activity. J Bone Miner Res.

27:913–925. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Underwood KF, Mochin MT, Brusgard JL, Choe

M, Gnatt A and Passaniti A: A quantitative assay to study protein:

DNA interactions, discover transcriptional regulators of gene

expression, and identify novel anti-tumor agents. J Vis Exp.

78:e505122013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Kim MS, Gernapudi R, Choi EY, Lapidus RG

and Passaniti A: Characterization of CADD522, a small molecule that

inhibits RUNX2-DNA binding and exhibits antitumor activity.

Oncotarget. 8:70916–70940. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Dobreva G, Dambacher J and Grosschedl R:

SUMO modification of a novel MAR-binding protein, SATB2, modulates

immunoglobulin mu gene expression. Genes Dev. 17:3048–3061. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y and Peng C:

Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and

circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9:4022018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Flynt AS and Lai EC: Biological principles

of microRNA-mediated regulation: Shared themes amid diversity. Nat

Rev Genet. 9:831–842. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Cameron KS, Buchner V and Tchounwou PB:

Exploring the molecular mechanisms of nickel-induced genotoxicity

and carcinogenicity: A literature review. Rev Environ Health.

26:81–92. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Lee JW, Bae SH, Jeong JW, Kim SH and Kim

KW: Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)alpha: Its protein stability

and biological functions. Exp Mol Med. 36:1–12. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Ke Q and Costa M: Hypoxia-inducible

factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol Pharmacol. 70:1469–1480. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Li Q, Chen H, Huang X and Costa M: Effects

of 12 metal ions on iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP-1) and

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-regulated

genes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 213:245–255. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Davidson TL, Chen H, Di Toro DM, D'Angelo

G and Costa M: Soluble nickel inhibits HIF-prolyl-hydroxylases

creating persistent hypoxic signaling in A549 cells. Mol Carcinog.

45:479–489. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Lee SH, Che X, Jeong JH, Choi JY, Lee YJ,

Lee YH, Bae SC and Lee YM: Runx2 protein stabilizes

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α through competition with von

Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL) and stimulates angiogenesis in growth

plate hypertrophic chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 287:14760–14771.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kwon TG, Zhao X, Yang Q, Li Y, Ge C, Zhao

G and Franceschi RT: Physical and functional interactions between

Runx2 and HIF-1α induce vascular endothelial growth factor gene

expression. J Cell Biochem. 112:3582–3593. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Dong W, Chen Y, Qian N, Sima G, Zhang J,

Guo Z and Wang C: SATB2 knockdown decreases hypoxia-induced

autophagy and stemness in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett.

20:794–802. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Ali T, Mushtaq I, Maryam S, Farhan A, Saba

K, Jan MI, Sultan A, Anees M, Duygu B, Hamera S, et al: Interplay

of N acetyl cysteine and melatonin in regulating oxidative

stress-induced cardiac hypertrophic factors and microRNAs. Arch

Biochem Biophys. 661:56–65. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Clemens F, Verma R, Ramnath J and Landolph

JR: Amplification of the Ect2 proto-oncogene and over-expression of

Ect2 mRNA and protein in nickel compound and

methylcholanthrene-transformed 10T1/2 mouse fibroblast cell lines.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 206:138–149. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Chiocca SM, Sterner DA, Biggart NW and

Murphy EC Jr: Nickel mutagenesis: Alteration of the MuSVts110

thermosensitive splicing phenotype by a nickel-induced duplication

of the 3′ splice site. Mol Carcinog. 4:61–71. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhang YJ, Chen JW, He XS, Zhang HZ, Ling

YH, Wen JH, Deng WH, Li P, Yun JP, Xie D and Cai MY: SATB2 is a

promising biomarker for identifying a colorectal origin for liver

metastatic adenocarcinomas. EBioMedicine. 28:62–69. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Dragomir A, de Wit M, Johansson C, Uhlen M

and Ponten F: The role of SATB2 as a diagnostic marker for tumors

of colorectal origin: Results of a pathology-based clinical