Proteins, the material basis of life, are essential

components of all cells, tissues and organs in the body.

Intracellular proteins are predominantly degraded through the

lysosomal pathway, cysteine-containing aspartate protease pathway

and ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (1–4). The

ubiquitin-proteasome system is the primary protein degradation

pathway in vivo. More than 80% of proteins in the body are

degraded through this pathway, which is involved in various

metabolic processes in the body (4). The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway can

degrade the cell cycle protein cyclin (5,6),

spindle-related proteins (7), cell

surface receptors such as epidermal growth factor (8), transcription factors (9), the tumor inhibitory factor p53 and

oncogenic products (10). In

addition, abnormal intracellular proteins are degraded by the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway under stress conditions. Ubiquitin,

ubiquitin-activating (E1) enzymes, ubiquitin-binding (E2) enzymes,

ubiquitin ligases (E3), protein hydrolases and deubiquitinating

enzymes are the main components of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

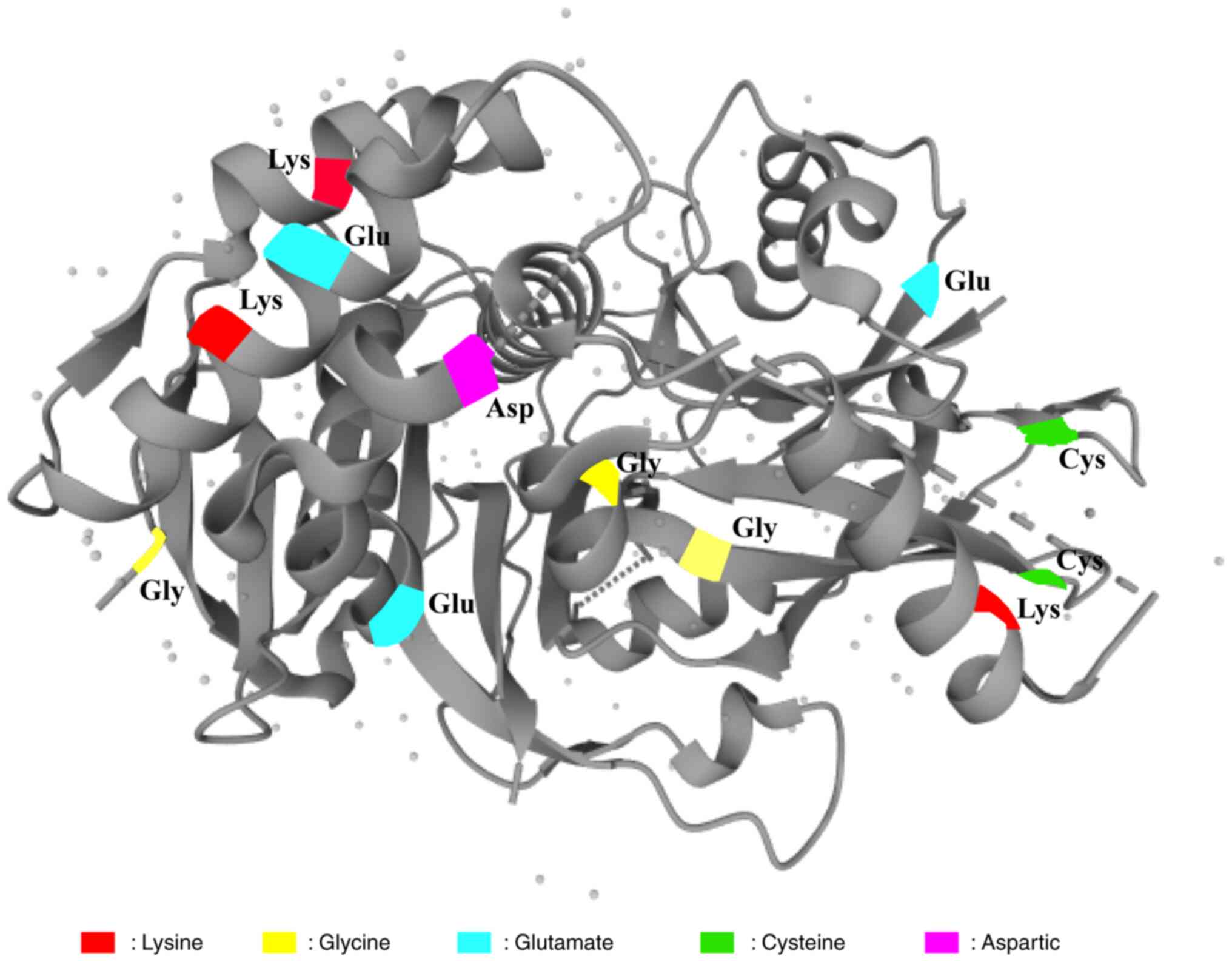

(9,11). In the presence of ATP, the glycine

(Gly) residue at the C-terminus of ubiquitin forms a high-energy

lipid bond with the sulfur group (SH) of the cysteine residue of an

E1 enzyme, and the activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred

to an E2 enzyme. In the presence of an E3 ubiquitin ligase,

ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 enzyme to the substrate

protein, forming an isopeptide bond with the ε-NH2 group of the Lys

residue of the substrate protein. Subsequently, the C-terminus of

the next ubiquitin molecule is connected to the Lys48 residue of

the previous ubiquitin molecule, thus completing

polyubiquitination. The ubiquitinated substrate proteins are

recognized by cap-shaped regulatory particles of the 19S proteasome

and transported into the cylindrical core of 20S, where they are

hydrolyzed into oligopeptides and amino acids by various enzymes

and are eventually released from the proteasome, thereby completing

ubiquitin-mediated degradation (12–14).

Ubiquitin molecules involved in ubiquitination are dissociated from

substrate proteins and can be reused in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). E3 ubiquitin ligases, which serve

a key role in ubiquitin-mediated degradation of proteins,

specifically mark the substrate proteins and attach ubiquitin to

them for degradation (9,15). Deubiquitination is an important

mechanism for maintaining intracellular protein stability and is

closely associated with the development of cancer. Deubiquitinating

enzymes (DUBs) hydrolyze the isopeptide bonds in ubiquitinated

substrate proteins, thereby dissociating the ubiquitinated

molecules from the substrate proteins and inhibiting

ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. A flowchart demonstrating

the mechanism of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is shown in

Fig. 1 (16–18).

DUBs are a large family of proteasomes. It is known that ~100 DUBs

are encoded by the human genome, which can be classified as

ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ubiquitin-specific

proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor-related proteases (OTUs),

Machado-Joseph disease (MJD) deubiquitinases and metalloproteases

(19–22). Except for the metalloproteinase

family, all other deubiquitinases are cysteine proteases; of which,

USPs are the most structurally diverse class of deubiquitinases

with the largest known membership. USPs inhibit protein degradation

by removing ubiquitin from substrate proteins through interaction

with a catalytic triplet of residues (cysteine, histidine and

aspartate) (23). USPs are involved

in regulation of apoptosis (23),

protein transport (24), regulation

of the cell cycle (25), DNA damage

repair (26), chromatin remodeling

and protein signaling (27,28). In addition to inhibiting the

degradation of ubiquitinated substrate proteins, USPs can regulate

related signaling pathways by affecting protein activity. For

example, in the TGF-β signaling pathway, USP15 and CYLD lysine 63

deubiquitinase (CYLD) affect the stability of the mothers against

decapentaplegic (SMAD) protein in Drosophila by antagonizing

SMAD protein-specific E3 ligase 2, which in turn negatively

regulates the activation of the TGF-β pathway (29). USP is involved in the regulation of

multiple cancer-related pathways, including p53,

Wnt/β-catenin, TGF-β and protein kinase B (Akt) pathways. For

example, the overexpression of USP2a stabilizes murine double

minute 2 (MDM2) through direct deubiquitination, thereby enhancing

the degradation of the tumor suppressor protein p53. The

downregulation of p53 eventually leads to tumor progression

(30). Overexpression of USP10

directly deubiquitinates and stabilizes Krüppel-like factor 4

protein, which directly binds to the promoter region of tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 (a tumor suppressor gene) to

promote its transcription and exert positive anti-tumor effects

(31).

Normal cell division, proliferation, differentiation

and ageing maintain the self-stability of the body. Cell cycle

disturbances can lead to abnormal cell proliferation, which is a

common feature of tumor cells (57). The role of USP2 in cell cycle

regulation has been well demonstrated (59,60).

CCND1 is abnormally overexpressed in various tumor cells. Shan

et al (61) screened 76 DUBs

in vitro to assess their catalytic ability to target CCND1.

They identified USP2 as a specific DUB of CCND1, which can directly

interact with CCND1, reduce the polymeric ubiquitination-dependent

degradation of CCND1 and promote tumor cell proliferation. In the

human embryonic kidney cell line 293T, USP2a has been shown to

deubiquitinate CCND1, thereby facilitating cell cycle progression

from the G1 to the S phase (38). A study demonstrated that the protein

expression of CCND1 is significantly higher in human breast cancer

MCF-7 cells and prostate cancer PC3 cells than in normal cells

(38). USP2 knockdown

attenuates CCND1 deubiquitination and stability, promotes

ubiquitin-mediated degradation, reduces CCND1 expression, inhibits

cell progression from the G1 to the S phase and

suppresses cell proliferation (38). In addition, USP2a is a

downstream target of lithocholic acid (LCA) hydroxyamide (LCAHA),

and LCAHA can destabilize CCND1 by inhibiting the expression of the

deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a (62). It induces

G0/G1 phase arrest in colon cancer cells

(HCT116), thus exerting an active anti-tumor effect (62). Leptin and adiponectin are two

hormones secreted by adipose tissue that have contradictory effects

on USP2 expression in tumor cells. Leptin targets USP2 to

upregulate the protein expression of CCND1 to promote cell cycle

progression and tumorigenesis(63).

Adiponectin targets USP2 to promote ubiquitin-mediated

degradation of CCND1 protein, resulting in cell cycle arrest and

inhibition of tumor progression (63). As the intracellular overexpression

of CCND1 is a decisive factor in the development of some tumors,

CCND1 has been used to assess the potential of USP2 inhibitors as

important indicators of the efficacy of antineoplastic drugs

(49,64). USP2 can directly recognize

and deubiquitinate CCND1, thereby preventing its degradation,

stabilizing its expression and promoting tumor development.

Similarly, USP2a can inhibit CCNA1 protein degradation through

deubiquitination, stabilize CCNA1 protein expression and promote

the progression of bladder cancer T24 cells from G1 to S

phase, which in turn promotes bladder cancer T24 cell proliferation

(65).

Aurora-A, a serine/threonine protein kinase, is a

mitotic regulator essential for the replication, maturation and

segregation of centrosomes and the subsequent spindle assembly.

Overexpression of Aurora-A inhibits Hec1 phosphorylation at serine

55 (Hec1-S55) during metaphase and destabilizes the

kinetochore-microtubule attachment, which in turn induces tumor

development (71,72). Shi et al (73) reported that USP2a reverses

ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Aurora-A and promotes mitosis in

pancreatic cancer MIA PaCa-2 cells. They used small interfering

RNAs (siRNAs) to knock down USP2a in MIA PaCa-2 cells, which

enhanced ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Aurora-A and

significantly inhibited the proliferation of tumor cells.

Therefore, USP2a may promote tumor cell proliferation by

stabilizing the Aurora-A protein, and targeting USP2a may

represent an effective strategy for inhibiting the abnormal

proliferation of tumor cells.

EMT is an important biological process in which

epithelial cells acquire the ability to migrate and invade

(74). TGF-β signaling can induce

the transcription of related genes, promote EMT and enhance the

migratory and invasive capabilities of tumor cells (75,76).

TGF-β binds to two types of transmembrane serine/threonine kinase

receptor heterologous complexes to initiate cellular responses

(77). Receptor kinases activate

the intracellular signaling protein SMAD to form heterologous

protein complexes that are transferred to the nucleus, where they

regulate the transcription of EMT-related genes, such as Snail,

Slug (zinc-finger proteins), Twist, N-cadherin and E-cadherin

(78). USP2a promotes the migratory

and invasive capabilities of non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells

by removing the K33-linked polyubiquitin chain from the TGF-β

receptor, thereby promoting the binding of receptor-regulated SMAD

(R-SMAD) to the TGF-β receptor and upregulating the expression of

Snail (79). A study demonstrated

that knockdown of USP2a or treatment with the USP2a-specific

inhibitor ML364 (10 µM) effectively inhibits the migratory and

invasive capabilities of tumor cells. In addition, ML364

significantly prolongs the survival of nude mice injected with

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Hep3B cells (via the tail vein) and

attenuated lung metastasis (79).

Therefore, USP2a may serve as a potential therapeutic target

for cancer.

Drug resistance and metastasis are the major causes

of death among patients with cancer. Developing effective

strategies for reversing drug resistance and elucidating mechanisms

underlying drug resistance constitute the primary focus of modern

medical research. Clinical conventional chemotherapeutic drugs

mainly exert their cytotoxic effects by inducing apoptosis through

the mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated

autophagic pathways (93–95). The anti-apoptotic regulator cFILP

serves an important role in death receptor signaling, and its

overexpression is one of the primary mechanisms through which tumor

cells acquire drug resistance (96,97).

On the one hand, cFILP competes with the precursor caspase-8 to

bind to Fas-associated death domain-containing protein (FADD),

which inhibits apoptosis and promotes drug resistance in tumor

cells (98). On the other hand,

cFILP interacts with Akt and enhances the anti-apoptotic function

of Akt by regulating the activity of glycogen synthase kinase-3 β

(GSK3β) to promote drug resistance in tumor cells (99,100).

Previous studies have reported that USP2 stabilizes the

protein expression of cFILP and promotes the proliferation of HCC

Huf7 cells through deubiquitination. Inhibition of USP2 can

reduce cFILP expression in sorafenib-resistant Huf7-SR cells,

promote apoptosis and increase sorafenib sensitivity (98). Additionally, USP2 negatively

regulates the expression of miRNA-1915-3P in oxaliplatin-resistant

colorectal cancer (CRC) cells; inhibits apoptosis and promotes the

proliferative, migratory and invasive capabilities of tumor cells.

Knockdown of USP2 promotes apoptosis and increases the

sensitivity of CRC cells to oxaliplatin (101). In addition, knockdown of

USP2 or treatment with ML363 enhances the sensitivity of

triple-negative breast cancer cells to doxorubicin (102).

In molecularly targeted therapy, specific oncogenes

or gene fragments can be targeted and corresponding targeted drugs

can be developed to act at the cellular level. When these targeted

drugs enter the human body, they specifically target the

cancer-inducing sites, leading to the specific elimination of tumor

cells without damaging normal cells (103–105). Therefore, molecularly targeted

therapy is considered an effective therapeutic strategy for cancer

in modern medicine and is a major focus of cancer research.

USP7, a member of the DUB family, can promote tumor

development by stabilizing the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2, promoting

p53 degradation and reducing the expression of downstream proteins

of p53 (106,107). Elevated USP7 expression is

closely associated with the development of several cancers and

USP7 is an important target for the treatment of prostate

cancer (108), malignant melanoma

(109), ovarian cancer (110), multiple myeloma (111) and CRC (112). In addition to USP7, other

USPs such as CYLD, USP1, USP6, USP8, USP9X, USP11, USP15 and

USP28, are considered potential therapeutic targets for

various cancers (23). Studies have

demonstrated that USP2, a multifunctional cysteine protease,

is a key regulator of ubiquitin-mediated degradation of fatty acid

synthase (FAS), MDM2, MDM4, epidermal growth factor receptor

(EGFR), the cell cycle proteins A1 and D1 and other oncogenic

proteins, and is closely associated with the development of a

number of tumors (59,91,106,113). Therefore, targeting USP2 is

a promising strategy for tumor treatment. This section discusses

the current research status of USP2 in cancer therapy and

summarizes the targets and related molecular mechanisms of

USP2 (Table I and Fig. 3).

The Twist protein is a highly conserved basic

helix-loop-helix transcription factor that is repressed in normal

tissue cells but overexpressed in triple-negative breast cancer and

various metastatic tumors (115,116). It serves a key role in the

self-renewal and EMT of tumor stem cells (117,118). USP2 is associated with the

upregulation of Twist protein in clinical tumor specimens.

Inhibition of USP2 expression promotes the

ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Twist, thereby inhibiting tumor

stem cell properties in vitro and tumorigenicity in

vivo (102). The USP2

inhibitor ML364 inhibits tumor growth and enhances the sensitivity

to Adriamycin (102). In addition,

the molecular chaperone function of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90)

serves a critical role in maintaining the stability of various

intracellular proteins and is closely associated with the

development of several tumors (119,120). Clinical trials have demonstrated

the anticancer effects of multiple HSP90 inhibitors, both as

monotherapy and combination therapy with ErbB2-targeting agents

(121,122). A preliminary clinical trial of

tanespimycin (17-AAG) provides additional evidence for the use of

HSP90 inhibitors in the treatment of ErbB2-positive breast cancer

(123). In a recent study, HSP90

inhibitors were found to promote the ubiquitin-mediated degradation

of ErbB2; however, these effects were reversed by USP2.

Additionally, ML364 not only enhanced the degradation of ErbB2 by

HSP90 inhibitors but also inhibited the growth of ErbB2-positive

breast cancer cells and transplanted tumors in mice in vivo

(56). Therefore, USP2 may

serve as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for breast

cancer.

Antisense RNAs refer to RNA molecules that are

complementary to mRNAs. They inhibit the translation of mRNAs and

block gene function by specifically and complementarily binding to

mRNAs (124). Given the medicinal

value of antisense RNAs, their role in cell growth and

differentiation needs to be intensively investigated (125). The expression of

ubiquitin-specific peptidase 2 antisense RNA 1 (lncRNA USP2-AS1), a

USP2-specific antisense RNA, is significantly higher in HCC tissues

than in paraneoplastic tissues. The high expression of USP2-AS1 is

significantly associated with a poorer prognosis. Knockdown of

USP2-AS1 promotes the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Y-box

binding protein 1-mediated hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; inhibits

the proliferative, migratory and invasive abilities of HCC cells

and reduces the tumorigenicity of HCC cells in mice (126).

Oxaliplatin is widely used as the first-line

chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of advanced CRC in

clinical settings. The expression of miRNA-1915-3P is reduced in

oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells and overexpression of miRNA-1915-3P

downregulates the oncogenes

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 and

USP2, thus inhibiting tumor proliferation, metastasis and

invasion (101). USP2 is a

negative regulator of miRNA-1915-3P. Overexpression of USP2

restores the proliferative capacity of tumor cells, whereas its

knockdown inhibits tumor cell proliferation (101). Therefore, small-molecule

inhibitors of USP2 may be used to induce oxaliplatin

sensitivity in advanced CRC.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is an astrocytic tumor

characterized by rapid growth, high malignancy and high mortality

rates (132). As a

cancer-promoting factor, TGF-β serves an important role in the

development of GBM (133,134). SMAD7, a key negative regulator of

TGF-β signaling, exerts its inhibitory effects on TGF-β by blocking

receptor activity and inducing receptor degradation (135). USP2 expression is

significantly lower in GBM tissues than in normal human brain

tissues and the prognosis of patients with lower USP2

expression is worse. Overexpression of USP2 can break the

isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and the Lys27 and Lys48 residues

of SMAD7 protein, reduce the recruitment of SMAD7 protein to the E3

ubiquitin ligase HERC3 and inhibit ubiquitin-mediated degradation

of SMAD7, thereby inhibiting the activation of the TGF-β signaling

pathway and the progression of GBM (54). Abnormal DNA methylation transferase

3A (DNMT3A)-mediated methylation of USP2 is the main cause

of low expression of USP2 in GBM tissues, and the DNMT3A

inhibitor GSI-1027 can induce USP2 expression to exert

anti-tumor effects against GBM (54).

Previous studies have reported that MDM4 can

promote endogenous apoptosis by regulating the expression of

oncogene p53 and that USP2a can interact with MDM4 to

inhibit its ubiquitin-mediated degradation (91,136,137). The expression of MDM4 and USP2a is

significantly lower in GBM tissues than in normal brain tissues and

is positively associated with the prognosis of GBM; that is, the

higher the expression, the more improved the prognosis. Knockdown

of USP2a promotes UV irradiation-induced cytochrome c

release, p53 protein expression and apoptosis in U87MG glioma

cells, whereas simultaneous upregulation of MDM4 can reverse these

effects (91). Therefore,

USP2 and MDM4 may serve as effective targets for the

treatment of GBM.

Bladder cancer is the most common life-threatening

tumor of the urinary system. Tight junction protein 1 (TJP1)

interacts with TWIST1 to enhance the invasive ability of tumor

cells and promotes bladder cancer progression by affecting vascular

remodeling (53). TJP1 expression

is significantly higher in clinical bladder cancer tissues compared

with healthy bladder tissues and is associated with tumor

angiogenesis and overall survival of patients (138). In vitro studies have

demonstrated that overexpression of TJP1 promotes the expression of

TWIST1 and chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) in tumor cells,

stimulating tumor cells to recruit more macrophages, which secrete

VEGF under CCL2 stimulation and enhance tumor angiogenesis.

Knockdown of TJP1 inhibits, and overexpression of TWIST1 promotes,

vascular remodeling in bladder cancer. TJP1 promotes vascular

remodeling by reversing ubiquitin-mediated degradation of TWIST1 by

recruiting USP2, whereas knockdown of USP2 promotes

ubiquitin-mediated degradation of TWIST1, reduces tumor

angiogenesis and exerts positive anti-tumor effects (53). In addition, USP2a gene is

highly expressed in bladder cancer cells and there is a physical

interaction between USP2a and CCNA1. USP2a inhibits

ubiquitination degradation of CCNA1 protein through

deubiquitylation, which in turn increases CCNA1 protein expression

and exerts a positive pro-oncogenic effect. Therefore, USP2

and TJP1 may serve as effective therapeutic targets for

bladder cancer.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is caused by the

clonal proliferation of T lymphocytes originating in the skin and

is a type of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Psoralen with

ultraviolet A (PUVA) phototherapy is a common treatment strategy

for CTCL in clinical settings (145,146). A study demonstrated that

USP2 is expressed in both quiescent and activated T

lymphocytes, and its expression is significantly reduced in

advanced CTCL. Treatment of MyLa2000 cells with PUVA or the

p53 agonist nutlin3a significantly increases the protein

expression of USP2 and p53 and promoted apoptosis (90). Silencing of USP2, which acts

as a tumor suppressor, reduces the protein expression of MDM2 and

enhances the transcriptional activity of p53, thereby

promoting apoptosis and enhancing the sensitivity of MyLa2000 cells

to PUVA and nutlin3a. In addition, p53 induced USP2

expression and stabilized MDM2 protein via deubiquitination, which

in turn inhibited the pro-apoptotic activity of p53, forming

a negative feedback loop (90).

Therefore, small-molecule inhibitors of USP2 may serve as

sensitizing agents in CTCL.

E2F transcription factor 4 (E2F4), a key factor

regulating cell cycle progression, binds to DNA to promote the

progression of cells from the G0 to the G1

and S phases and is involved in tumor progression (147). E2F4 can directly regulate

the transcription of ATG2A and ULK2 proteins, leading to the

autophagic degradation of metallothionein; it can maintain zinc

homeostasis in tumor cells and promote the proliferative, migratory

and invasive abilities of gastric cancer cells (59). High expression of USP2 and

E2F4 in gastric cancer tissues is associated with a poor

prognosis. Emetine, an autophagy inhibitor, can block the

interaction between USP2 and E2F4 and promote E2F4 degradation for

an oncogenic effect, which can be reversed upon USP2

overexpression (59). Therefore,

USP2 and E2F4 may serve as potential biomarkers for

maintaining zinc homeostasis in the treatment of gastric

cancer.

Previous studies have demonstrated the involvement

of multiple USPs in the tumorigenesis and chemotherapy resistance

of lung cancer (148,149). USPs may serve as therapeutic

targets for lung cancer. For instance, inhibition of USP1

and USP51 can increase cisplatin sensitivity in lung cancer

(150,151); inhibition of USP5 and

USP28 can promote apoptosis of tumor cells (152,153) and promotion of USP52 and USP7 can

inhibit the proliferative, migratory and invasive abilities of lung

cancer cells (107,154). However, the role of USP2 in lung

cancer remains elusive. Zhang et al (155) reported that USP2 expression is

upregulated in the lung cancer cell lines H1229 and H1270.

Knockdown of USP2 promotes ubiquitin-mediated degradation of SKP2

and inhibits the growth of tumor cells. Mechanistically, USP2

interacts with SKP2 and stabilizes its expression to promote lung

cancer progression. Therefore, USP2 and SKP2 may

serve as potential therapeutic targets for lung cancer.

Renal clear cell carcinoma is a common malignant

tumor of the urinary system. The proliferation and apoptosis of

cancer cells cannot be achieved without the participation of USPs

(156,157). The clinical significance of

USP2 in renal clear cell carcinoma has been demonstrated

(158). The mRNA and protein

expression of USP2 is significantly lower in cancer tissues than in

para-cancerous and healthy kidney tissues. Studies have verified

the low protein expression of USP2 in most cancer tissues

via immunohistochemical analysis (56,159,160). Overexpression of USP2

inhibits the proliferative, migratory and invasive abilities of

kidney cancer cells (A498 and CAKi-1) (158). In addition, the abnormal

expression of USP2 is closely related to the clinical stage,

pathological grade and prognosis of patients with renal cancer, and

USP2 has been identified as an independent risk factor for

renal clear cell carcinoma (158).

Therefore, USP2 is a potential target for the diagnosis and

treatment of renal clear cell carcinoma.

With the rapid development of structural biology

and small-molecule drugs, targeted therapy has emerged as the most

promising strategy in clinical tumor treatment. Recent studies have

revealed the role of DUBs in life activities and identified DUBs as

potential therapeutic targets for tumors (170). USP2 is closely associated

with the development of various tumors, such as breast cancer,

liver cancer, CRC, GBM and hematological tumors (49,53,54,56,126).

At present, ML364 is the most common small-molecule inhibitor used

in clinical trials; other inhibitors include Q29, STD1T and LCAHA

(23). The chemical structures of

these small-molecule inhibitors are shown in Fig. 4, and key information regarding their

mechanism of action and targets is summarized in Table II. The use of USP2 as a

target for tumor treatment has received increasing attention from

researchers. Although several USP2-targeted agents have

shown positive anticancer effects in different cancers, the

identified targeting agents are undergoing preclinical

investigation at present. Therefore, these agents should be

evaluated via complex and comprehensive techniques to provide a

theoretical basis for their clinical application.

LCA, a secondary bile acid, serves an important

role in lipid metabolism, and several derivatives of LCA have

anticancer activity (173,174). The most active, LCAHA (Fig. 4C; IC50=5.8 µM), can

directly inhibit the biological activity of USP2a, induce

G0/G1-phase arrest in HCT116 cells and

ubiquitously degrade cell cycle protein D1, thereby exerting

positive anticancer effects (62).

6-TG is a clinical agent for the treatment of AML

and chronic granulocytic leukemia (161,162) (Fig.

4E). Chuang et al (139) used enzyme kinetic and X-ray

crystallographic data to verify that 6-TG is a small-molecule

inhibitor of USP2 that forms covalent bonds with the Cys276

residue of USP2 to inhibit its expression. This finding

provides a rationale for the clinical use of 6-TG in the treatment

of tumors with USP2 upregulation.

Chalcones, members of the flavonoid family, can

regulate the malignant behavior of tumors, such as tumor accretion,

invasion and metastasis, by targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome

system (176,177). Issaenko et al (178) found that the chalcone derivative

RA-9 (Fig. 4G) inhibits the

activity of USP2, USP5 and USP8; downregulates the expression of

CCND1 in breast, ovarian and cervical cancer cells, upregulates the

expression of oncogenes p53, p27 and p16 to promote

apoptosis and exerts positive anticancer effects.

Ubiquitination, one of the post-translational

modifications, serves an important role in the development and

malignant behavior of several cancers and influences protein

expression and signal transduction. DUBs can regulate the stability

of substrate proteins by removing ubiquitin tags, thereby

regulating the cascade responses of the cell cycle, DNA damage

repair, invasion, metastasis and other signaling pathways.

Targeting DUBs represents an effective strategy for the treatment

of cancer. Some USP-targeted drugs are undergoing investigation in

phase II clinical trials. USP2 primarily influences the expression

of CCND1, MDM2, p53 and other proteins by regulating

ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, which in turn affects tumor

development. However, the following questions remain to be

addressed: i) How do transcription factors recognize USP2

and regulate its transcription? ii) In addition to affecting the

cell cycle and cell death, does USP2 regulate other

biological processes? iii) What are the specific molecular

mechanisms through which USP2 regulates the expression of

related factors?

Not applicable.

The present study was funded by The National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82260535) and The 2022 National

Foundation incubation Program of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou

Medical University (grant no. gyfynsfc-2022-7).

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as

no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current

study.

SLZ, YG, and SJZ contributed to the review of data

collection, manuscript writing and revision. SZ was involved in the

consultation process and article revision. YWZ and ZW participated

in the collection and arrangement of materials.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Ding Y, Xing D, Fei Y and Lu B: Emerging

degrader technologies engaging lysosomal pathways. Chem Soc Rev.

51:8832–8876. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jiang TY, Shi YY, Cui XW, Pan YF, Lin YK,

Feng XF, Ding ZW, Yang C, Tan YX, Dong LW and Wang HY: PTEN

deficiency facilitates exosome secretion and metastasis in

cholangiocarcinoma by impairing TFEB-mediated lysosome biogenesis.

Gastroenterology. 164:424–438. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Karbowski M, Oshima Y and Verhoeven N:

Mitochondrial proteotoxicity: implications and ubiquitin-dependent

quality control mechanisms. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:5742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sinam IS, Chanda D, Thoudam T, Kim MJ, Kim

BG, Kang HJ, Lee JY, Baek SH, Kim SY, Shim BJ, et al: Pyruvate

dehydrogenase kinase 4 promotes ubiquitin-proteasome

system-dependent muscle atrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle.

13:3122–3136. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

O'Brien S, Kelso S, Steinhart Z, Orlicky

S, Mis M, Kim Y, Lin S, Sicheri F and Angers S: SCF

FBXW7 regulates G2-M progression through control of

CCNL1 ubiquitination. EMBO Rep. 23:e550442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Capecchi MR and Pozner A: ASPM regulates

symmetric stem cell division by tuning Cyclin E ubiquitination. Nat

Commun. 6:87632015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang L, Li Q, Yang J, Xu P, Xuan Z, Xu J

and Xu Z: Cytosolic TGM2 promotes malignant progression in gastric

cancer by suppressing the TRIM21-mediated

ubiquitination/degradation of STAT1 in a GTP binding-dependent

modality. Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:123–149. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Feng X, Jia Y, Zhang Y, Ma F, Zhu Y, Hong

X, Zhou Q, He R, Zhang H, Jin J, et al: Ubiquitination of UVRAG by

SMURF1 promotes autophagosome maturation and inhibits

hepatocellular carcinoma growth. Autophagy. 15:1130–1149. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li H, Wang N, Jiang Y, Wang H, Xin Z, An

H, Pan H, Ma W, Zhang T, Wang X and Lin W: E3 ubiquitin ligase

NEDD4L negatively regulates inflammation by promoting

ubiquitination of MEKK2. EMBO Rep. 23:e546032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nan Y, Luo Q, Wu X, Chang W, Zhao P, Liu S

and Liu Z: HCP5 prevents ubiquitination-mediated UTP3 degradation

to inhibit apoptosis by activating c-Myc transcriptional activity.

Mol Ther. 31:552–568. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cao HJ, Jiang H, Ding K, Qiu XS, Ma N,

Zhang FK, Wang YK, Zheng QW, Xia J, Ni QZ, et al: ARID2 mitigates

hepatic steatosis via promoting the ubiquitination of JAK2. Cell

Death Differ. 30:383–396. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mattiroli F and Penengo L: Histone

ubiquitination: An integrative signaling platform in genome

stability. Trends Genet. 37:566–581. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Roberts JZ, Crawford N and Longley DB: The

role of ubiquitination in apoptosis and necroptosis. Cell Death

Differ. 29:272–284. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang K, Liu J, Li YL, Li JP and Zhang R:

Ubiquitination/de-ubiquitination: A promising therapeutic target

for PTEN reactivation in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1877:1887232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu J, Wei L, Hu N, Wang D, Ni J, Zhang S,

Liu H, Lv T, Yin J, Ye M and Song Y: FBW7-mediated ubiquitination

and destruction of PD-1 protein primes sensitivity to anti-PD-1

immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

10:e0051162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu Z, Wang T, She Y, Wu K, Gu S, Li L,

Dong C, Chen C and Zhou Y: N6-methyladenosine-modified

circIGF2BP3 inhibits CD8+ T-cell responses to facilitate

tumor immune evasion by promoting the deubiquitination of PD-L1 in

non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 20:1052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wu L, Zhao N, Zhou Z, Chen J, Han S, Zhang

X, Bao H, Yuan W and Shu X: PLAGL2 promotes the proliferation and

migration of gastric cancer cells via USP37-mediated

deubiquitination of Snail1. Theranostics. 11:700–714. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xie H, Zhou J, Liu X, Xu Y, Hepperla AJ,

Simon JM, Wang T, Yao H, Liao C, Baldwin AS, et al: USP13 promotes

deubiquitination of ZHX2 and tumorigenesis in kidney cancer. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 119:e21198541192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rasaei R, Sarodaya N, Kim KS, Ramakrishna

S and Hong SH: Importance of deubiquitination in

macrophage-mediated viral response and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci.

21:80902020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sun T, Liu Z and Yang Q: The role of

ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer metabolism. Mol

Cancer. 19:1462020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cai J, Culley MK, Zhao Y and Zhao J: The

role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in the regulation of

cell junctions. Protein Cell. 9:754–769. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhou Y, Park SH and Chua NH:

UBP12/UBP13-mediated deubiquitination of salicylic acid receptor

NPR3 suppresses plant immunity. Mol Plant. 16:232–244. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen S, Liu Y and Zhou H: Advances in the

development ubiquitin-specific peptidase (USP) inhibitors. Int J

Mol Sci. 22:45462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sato Y, Goto E, Shibata Y, Kubota Y,

Yamagata A, Goto-Ito S, Kubota K, Inoue J, Takekawa M, Tokunaga F

and Fukai S: Structures of CYLD USP with Met1- or Lys63-linked

diubiquitin reveal mechanisms for dual specificity. Nat Struct Mol

Biol. 22:222–229. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Maertens GN, El Messaoudi-Aubert S,

Elderkin S, Hiom K and Peters G: Ubiquitin-specific proteases 7 and

11 modulate Polycomb regulation of the INK4a tumour suppressor.

EMBO J. 29:2553–2565. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Cruz L, Soares P and Correia M:

Ubiquitin-Specific proteases: Players in cancer cellular processes.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 14:8482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mansilla A, Martin FA, Martin D and Ferrus

A: Ligand-independent requirements of steroid receptors EcR and USP

for cell survival. Cell Death Differ. 23:405–416. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

An Z, Liu Y, Ou Y, Li J, Zhang B, Sun D,

Sun Y and Tang W: Regulation of the stability of RGF1 receptor by

the ubiquitin-specific proteases UBP12/UBP13 is critical for root

meristem maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:1123–1128. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lim JH, Jono H, Komatsu K, Woo CH, Lee J,

Miyata M, Matsuno T, Xu X, Huang Y, Zhang W, et al: CYLD negatively

regulates transforming growth factor-β-signalling via

deubiquitinating Akt. Nat Commun. 3:7712012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bonacci T and Emanuele MJ: Dissenting

degradation: Deubiquitinases in cell cycle and cancer. Semin Cancer

Biol. 67((Pt 2)): 145–158. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang X, Xia S, Li H, Wang X, Li C, Chao Y,

Zhang L and Han C: The deubiquitinase USP10 regulates KLF4

stability and suppresses lung tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ.

27:1747–1764. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Baek SH, Choi KS, Yoo YJ, Cho JM, Baker

RT, Tanaka K and Chung CH: Molecular cloning of a novel

ubiquitin-specific protease, UBP41, with isopeptidase activity in

chick skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 272:25560–25565. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gousseva N and Baker RT: Gene structure,

alternate splicing, tissue distribution, cellular localization, and

developmental expression pattern of mouse deubiquitinating enzyme

isoforms Usp2-45 and Usp2-69. Gene Expr. 11:163–179. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Moremen KW, Touster O and Robbins PW:

Novel purification of the catalytic domain of Golgi

alpha-mannosidase II. Characterization and comparison with the

intact enzyme. J Biol Chem. 266:16876–16885. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, Shenmen

CM, Grouse LH, Schuler G, Klein SL, Old S, Rasooly R, Good P, et

al: The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA

project: The Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC). Genome Res.

14((10B)): 2121–2127. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T,

Sugiyama T, Irie R, Wakamatsu A, Hayashi K, Sato H, Nagai K, et al:

Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length

human cDNAs. Nat Genet. 36:40–45. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Luo H, Ji Y, Gao X, Liu X and Wu Y and Wu

Y: Ubiquitin specific protease 2: Structure, isoforms, cellular

function, relateddiseases and its inhibitors. Oncologie. 24:85–99.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhu HQ and Gao FH: The molecular

mechanisms of regulation on USP2′s alternative splicing and the

significance of its products. Int J Biol Sci. 13:1489–1496. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pouly D, Chenaux S, Martin V, Babis M,

Koch R, Nagoshi E, Katanaev VL, Gachon F and Staub O: USP2-45 is a

circadian clock output effector regulating calcium absorption at

the post-translational level. PLoS One. 11:e01451552016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Tong X, Buelow K, Guha A, Rausch R and Yin

L: USP2a protein deubiquitinates and stabilizes the circadian

protein CRY1 in response to inflammatory signals. J Biol Chem.

287:25280–25291. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Molusky MM, Li S, Ma D, Yu L and Lin JD:

Ubiquitin-specific protease 2 regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis and

diurnal glucose metabolism through 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

1. Diabetes. 61:1025–1035. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kitamura H, Kimura S, Shimamoto Y, Okabe

J, Ito M, Miyamoto T, Naoe Y, Kikuguchi C, Meek B, Toda C, et al:

Ubiquitin-specific protease 2–69 in macrophages potentially

modulates metainflammation. FASEB J. 27:4940–4953. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang S, Wu H, Liu Y, Sun J, Zhao Z, Chen

Q, Guo M, Ma D and Zhang Z: Expression of USP2-69 in mesangial

cells in vivo and in vitro. Pathol Int. 60:184–192. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Haimerl F, Erhardt A, Sass G and Tiegs G:

Down-regulation of the de-ubiquitinating enzyme ubiquitin-specific

protease 2 contributes to tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced

hepatocyte survival. J Biol Chem. 284:495–504. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li Y, Kim BG, Qian S, Letterio JJ, Fung

JJ, Lu L and Lin F: Hepatic stellate cells inhibit T cells through

active TGF-β1 from a cell surface-bound latent TGF-β1/GARP complex.

J Immunol. 195:2648–2656. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Mao X, Luo W, Sun J, Yang N, Zhang LW,

Zhao Z, Zhang Z and Wu H: Usp2-69 overexpression slows down the

progression of rat anti-Thy1.1 nephritis. Exp Mol Pathol.

101:249–258. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kitamura H, Ishino T, Shimamoto Y, Okabe

J, Miyamoto T, Takahashi E and Miyoshi I: Ubiquitin-Specific

protease 2 modulates the lipopolysaccharide-elicited expression of

proinflammatory cytokines in macrophage-like HL-60 cells. Mediators

Inflamm. 2017:69094152017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Mahul-Mellier AL, Datler C, Pazarentzos E,

Lin B, Chaisaklert W, Abuali G and Grimm S: De-ubiquitinating

proteases USP2a and USP2c cause apoptosis by stabilising RIP1.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1823:1353–1365. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Davis MI, Pragani R, Fox JT, Shen M,

Parmar K, Gaudiano EF, Liu L, Tanega C, McGee L, Hall MD, et al:

Small molecule inhibition of the ubiquitin-specific protease USP2

Accelerates cyclin D1 degradation and leads to cell cycle arrest in

colorectal cancer and mantle cell lymphoma models. J Biol Chem.

291:24628–24640. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Bedard N, Yang Y, Gregory M, Cyr DG,

Suzuki J, Yu X, Chian RC, Hermo L, O'Flaherty C, Smith CE, et al:

Mice lacking the USP2 deubiquitinating enzyme have severe male

subfertility associated with defects in fertilization and sperm

motility. Biol Reprod. 85:594–604. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Xu Q, Liu M, Zhang F, Liu X, Ling S, Chen

X, Gu J, Ou W, Liu S and Liu N: Ubiquitin-specific protease 2

regulates Ang II-induced cardiac fibroblasts activation by

up-regulating cyclin D1 and stabilizing β-catenin in vitro. J Cell

Mol Med. 25:1001–1011. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hashimoto M, Fujimoto M, Konno K, Lee ML,

Yamada Y, Yamashita K, Toda C, Tomura M, Watanabe M, Inanami O and

Kitamura H: Ubiquitin-Specific protease 2 in the ventromedial

hypothalamus modifies blood glucose levels by controlling

sympathetic nervous activation. J Neurosci. 42:4607–4618. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liu XQ, Shao XR, Liu Y, Dong ZX, Chan SH,

Shi YY, Chen SN, Qi L, Zhong L, Yu Y, et al: Tight junction protein

1 promotes vasculature remodeling via regulating USP2/TWIST1 in

bladder cancer. Oncogene. 41:502–514. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Tu Y, Xu L, Xu J, Bao Z, Tian W, Ye Y, Sun

G, Miao Z, Chao H, You Y, et al: Loss of deubiquitylase USP2

triggers development of glioblastoma via TGF-β signaling. Oncogene.

41:2597–2608. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Nadolny C, Zhang X, Chen Q, Hashmi SF, Ali

W, Hemme C, Ahsan N, Chen Y and Deng R: Dysregulation and

activities of ubiquitin specific peptidase 2b in the pathogenesis

of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 11:4746–4767.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang J, Liu S, Li Q, Shi Y, Wu Y, Liu F,

Wang S, Zaky MY, Yousuf W, Sun Q, et al: The deubiquitylase USP2

maintains ErbB2 abundance via counteracting endocytic degradation

and represents a therapeutic target in ErbB2-positive breast

cancer. Cell Death Differ. 27:2710–2725. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Qu Q, Mao Y, Xiao G, Fei X, Wang J, Zhang

Y, Liu J, Cheng G, Chen X, Wang J and Shen K: USP2 promotes cell

migration and invasion in triple negative breast cancer cell lines.

Tumour Biol. 36:5415–5423. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liang XR, Liu YF, Chen F, Zhou ZX, Zhang

LJ and Lin ZJ: Cell Cycle-Related lncRNAs as innovative targets to

advance cancer management. Cancer Manag Res. 15:547–561. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Xiao W, Wang J, Wang X, Cai S, Guo Y, Ye

L, Li D, Hu A, Jin S, Yuan B, et al: Therapeutic targeting of the

USP2-E2F4 axis inhibits autophagic machinery essential for zinc

homeostasis in cancer progression. Autophagy. 18:2615–2635. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhu M, Wang H, Ding Y, Yang Y, Xu Z, Shi L

and Zhang N: Ribonucleotide reductase holoenzyme inhibitor COH29

interacts with deubiquitinase ubiquitin-specific protease 2 and

downregulates its substrate protein cyclin D1. FASEB J.

36:e223292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Shan J, Zhao W and Gu W: Suppression of

cancer cell growth by promoting cyclin D1 degradation. Mol Cell.

36:469–476. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Magiera K, Tomala M, Kubica K, De Cesare

V, Trost M, Zieba BJ, Kachamakova-Trojanowska N, Les M, Dubin G,

Holak TA and Skalniak L: Lithocholic acid hydroxyamide destabilizes

cyclin D1 and Induces G (0)/G (1) arrest by inhibiting

deubiquitinase USP2a. Cell Chem Biol. 24:458–470. e182017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Nepal S, Shrestha A and Park PH: Ubiquitin

specific protease 2 acts as a key modulator for the regulation of

cell cycle by adiponectin and leptin in cancer cells. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 412:44–55. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Tomala MD, Magiera-Mularz K, Kubica K,

Krzanik S, Zieba B, Musielak B, Pustula M, Popowicz GM, Sattler M,

Dubin G, et al: Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of

USP2a. Eur J Med Chem. 150:261–267. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kim J, Kim WJ, Liu Z, Loda M and Freeman

MR: The ubiquitin-specific protease USP2a enhances tumor

progression by targeting cyclin A1 in bladder cancer. Cell Cycle.

11:1123–1130. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Gabay M, Li Y and Felsher DW: MYC

activation is a hallmark of cancer initiation and maintenance. Cold

Spring Harb Perspect Med. 4:a0142412014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Stine ZE, Walton ZE, Altman BJ, Hsieh AL

and Dang CV: MYC, Metabolism, and Cancer. Cancer Discov.

5:1024–1039. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wu CH, van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Fan AC,

Bachireddy P and Felsher DW: Cellular senescence is an important

mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 104:13028–13033. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Zhuang D, Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Tang

WH, Patil S, Wawrzyniak JA, Berman AE, Giordano TJ, Prochownik EV,

Soengas MS and Nikiforov MA: C-MYC overexpression is required for

continuous suppression of oncogene-induced senescence in melanoma

cells. Oncogene. 27:6623–6634. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Li B, Zhang G, Wang Z, Yang Y, Wang C,

Fang D, Liu K, Wang F and Mei Y: c-Myc-activated USP2-AS1

suppresses senescence and promotes tumor progression via

stabilization of E2F1 mRNA. Cell Death Dis. 12:10062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Iemura K, Natsume T, Maehara K, Kanemaki

MT and Tanaka K: Chromosome oscillation promotes Aurora A-dependent

Hec1 phosphorylation and mitotic fidelity. J Cell Biol.

220:e2020061162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Li P, Chen T, Kuang P, Liu F, Li Z, Liu F,

Wang Y, Zhang W and Cai X: Aurora-A/FOXO3A/SKP2 axis promotes tumor

progression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and dual-targeting

Aurora-A/SKP2 shows synthetic lethality. Cell Death Dis.

13:6062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Shi Y, Solomon LR, Pereda-Lopez A, Giranda

VL, Luo Y, Johnson EF, Shoemaker AR, Leverson J and Liu X:

Ubiquitin-specific cysteine protease 2a (USP2a) regulates the

stability of Aurora-A. J Biol Chem. 286:38960–38968. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Gu Y, Zhang Z, Camps MGM, Ossendorp F,

Wijdeven RH and Ten Dijke P: Genome-wide CRISPR screens define

determinants of epithelial-mesenchymal transition mediated immune

evasion by pancreatic cancer cells. Sci Adv. 9:eadf99152023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Chen J, Ding ZY, Li S, Liu S, Xiao C, Li

Z, Zhang BX, Chen XP and Yang X: Targeting transforming growth

factor-β signaling for enhanced cancer chemotherapy. Theranostics.

11:1345–1363. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

He Q, Cao H, Zhao Y, Chen P, Wang N, Li W,

Cui R, Hou P, Zhang X and Ji M: Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Stabilizes

Integrin alpha4β1 complex to promote thyroid cancer cell metastasis

by activating transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway.

Thyroid. 32:1411–1422. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Tuersuntuoheti A, Li Q, Teng Y, Li X,

Huang R, Lu Y, Li K, Liang J, Miao S, Wu W and Song W: YWK-II/APLP2

inhibits TGF-β signaling by interfering with the TGFBR2-Hsp90

interaction. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. Jul 19–2023.(Epub

ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Miyazawa K and Miyazono K: Regulation of

TGF-β family signaling by inhibitory smads. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 9:a0220952017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Zhao Y, Wang X, Wang Q, Deng Y, Li K,

Zhang M, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Wang HY, Bai P, et al: USP2a supports

metastasis by tuning TGF-β signaling. Cell Rep. 22:2442–2454. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Blenman KRM, Marczyk M, Karn T, Qing T, Li

X, Gunasekharan V, Yaghoobi V, Bai Y, Ibrahim EY, Park T, et al:

Predictive markers of response to neoadjuvant durvalumab with

nab-paclitaxel and dose-dense doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide in

basal-like triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

28:2587–2597. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Cui Y, Zhao M, Yang Y, Xu R, Tong L, Liang

J, Zhang X, Sun Y and Fan Y: Reversal of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and inhibition of tumor stemness of breast cancer cells

through advanced combined chemotherapy. Acta Biomater. 152:380–392.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Ahangari F, Becker C, Foster DG,

Chioccioli M, Nelson M, Beke K, Wang X, Justet A, Adams T, Readhead

B, et al: Saracatinib, a selective src kinase inhibitor, blocks

fibrotic responses in preclinical models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am

J Respir Crit Care Med. 206:1463–1479. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

van der Wal T and van Amerongen R: Walking

the tight wire between cell adhesion and WNT signalling: A

balancing act for beta-catenin. Open Biol. 10:2002672020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kim J, Alavi Naini F, Sun Y and Ma L:

Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 2a (USP2a) deubiquitinates and

stabilizes β-catenin. Am J Cancer Res. 8:1823–1836, eCollection

2018. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Pichiorri F, Suh SS, Rocci A, De Luca L,

Taccioli C, Santhanam R, Zhou W, Benson DM Jr, Hofmainster C, Alder

H, et al: Retraction notice to: Downregulation of p53-inducible

microRNAs 192, 194, and 215 Impairs the p53/MDM2 autoregulatory

loop in multiple myeloma development. Cancer Cell. 40:14412022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wu B and Ellisen LW: Loss of p53 and

genetic evolution in pancreatic cancer: Ordered chaos after the

guardian is gone. Cancer Cell. 40:1276–1278. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Hassin O and Oren M: Drugging p53 in

cancer: One protein, many targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22:127–144.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Dobbelstein M and Levine AJ: Mdm2: Open

questions. Cancer Sci. 111:2203–2211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Stevenson LF, Sparks A, Allende-Vega N,

Xirodimas DP, Lane DP and Saville MK: The deubiquitinating enzyme

USP2a regulates the p53 pathway by targeting Mdm2. EMBO J.

26:976–986. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Wei T, Biskup E, Gjerdrum LM, Niazi O,

Odum N and Gniadecki R: Ubiquitin-specific protease 2 decreases

p53-dependent apoptosis in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget.

7:48391–48400. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Wang CL, Wang JY, Liu ZY, Ma XM, Wang XW,

Jin H, Zhang XP, Fu D, Hou LJ and Lu YC: Ubiquitin-specific

protease 2a stabilizes MDM4 and facilitates the p53-mediated

intrinsic apoptotic pathway in glioblastoma. Carcinogenesis.

35:1500–1509. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Shrestha M and Park PH: p53 signaling is

involved in leptin-induced growth of hepatic and breast cancer

cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 20:487–498. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chen W, Shi K, Liu J, Yang P, Han R, Pan

M, Yuan L, Fang C, Yu Y and Qian Z: Sustained co-delivery of

5-fluorouracil and cis-platinum via biodegradable thermo-sensitive

hydrogel for intraoperative synergistic combination chemotherapy of

gastric cancer. Bioact Mater. 23:1–15. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Wang J, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Xiang L, Pang H,

Xiong K, Lu Y, Li J, Dai J, Lin S and Fu S: Radiotherapy-induced

enrichment of EGF-modified doxorubicin nanoparticles enhances the

therapeutic outcome of lung cancer. Drug Deliv. 29:588–599. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Smith ER, Wang JQ, Yang DH and Xu XX:

Paclitaxel resistance related to nuclear envelope structural

sturdiness. Drug Resist Updat. 65:1008812022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Jang JH, Lee TJ, Sung EG, Song IH and Kim

JY: Dapagliflozin induces apoptosis by downregulating

cFILPL and increasing cFILPS instability in

Caki-1 cells. Oncol Lett. 24:4012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Poukkula M, Kaunisto A, Hietakangas V,

Denessiouk K, Katajamaki T, Johnson MS, Sistonen L and Eriksson JE:

Rapid turnover of c-FLIPshort is determined by its unique

C-terminal tail. J Biol Chem. 280:27345–27355. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Liu D, Fan Y, Li J, Cheng B, Lin W, Li X,

Du J and Ling C: Inhibition of cFLIP overcomes acquired resistance

to sorafenib via reducing ER stress-related autophagy in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 40:2206–2214. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Iyer AK, Azad N, Talbot S, Stehlik C, Lu

B, Wang L and Rojanasakul Y: Antioxidant c-FLIP inhibits Fas

ligand-induced NF-kappaB activation in a phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase/Akt-dependent manner. J Immunol. 187:3256–3266. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Quintavalle C, Incoronato M, Puca L,

Acunzo M, Zanca C, Romano G, Garofalo M, Iaboni M, Croce CM and

Condorelli G: c-FLIPL enhances anti-apoptotic Akt functions by

modulation of Gsk3β activity. Cell Death Differ. 24:11342017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Xiao Z, Liu Y, Li Q, Liu Q, Liu Y, Luo Y

and Wei S: EVs delivery of miR-1915-3p improves the

chemotherapeutic efficacy of oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 88:1021–1031. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

He J, Lee HJ, Saha S, Ruan D, Guo H and

Chan CH: Inhibition of USP2 eliminates cancer stem cells and

enhances TNBC responsiveness to chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis.

10:2852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Min HY and Lee HY: Molecular targeted

therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med. 54:1670–1694. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Assoun S, Lemiale V and Azoulay E:

Molecular targeted therapy-related life-threatening toxicity in

patients with malignancies. A systematic review of published cases.

Intensive Care Med. 45:988–997. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Rosenberg T, Yeo KK, Mauguen A,

Alexandrescu S, Prabhu SP, Tsai JW, Malinowski S, Joshirao M,

Parikh K, Farouk Sait S, et al: Upfront molecular targeted therapy

for the treatment of BRAF-mutant pediatric high-grade glioma. Neuro

Oncol. 24:1964–1975. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Harakandi C, Nininahazwe L, Xu H, Liu B,

He C, Zheng YC and Zhang H: Recent advances on the intervention

sites targeting USP7-MDM2-p53 in cancer therapy. Bioorg Chem.

116:1052732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Huang YT, Cheng AC, Tang HC, Huang GC, Cai

L, Lin TH, Wu KJ, Tseng PH, Wang GG and Chen WY: USP7 facilitates

SMAD3 autoregulation to repress cancer progression in p53-deficient

lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 12:8802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Park SH, Fong KW, Kim J, Wang F, Lu X, Lee

Y, Brea LT, Wadosky K, Guo C, Abdulkadir SA, et al:

Posttranslational regulation of FOXA1 by Polycomb and BUB3/USP7

deubiquitin complex in prostate cancer. Sci Adv. 7:eabe22612021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Su D, Wang W, Hou Y, Wang L, Yi X, Cao C,

Wang Y, Gao H, Wang Y, Yang C, et al: Bimodal regulation of the

PRC2 complex by USP7 underlies tumorigenesis. Nucleic Acids Res.

49:4421–4440. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Zhang L, Wang H, Tian L and Li H:

Expression of USP7 and MARCH7 is correlated with poor prognosis in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 239:165–175. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Liu M, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Jin J, Cao Y, Fang

Z, Geng L, Yang L, Yu M, Bu Z, et al: IKZF1 selectively enhances

homologous recombination repair by interacting with CtIP and USP7

in multiple myeloma. Int J Biol Sci. 18:2515–2526. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Zhu Y, Gu L, Lin X, Cui K, Liu C, Lu B,

Zhou F, Zhao Q, Shen H and Li Y: LINC00265 promotes colorectal

tumorigenesis via ZMIZ2 and USP7-mediated stabilization of

β-catenin. Cell Death Differ. 27:1316–1327. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Ullah S, Junaid M, Liu Y, Chen S, Zhao Y

and Wadood A: Validation of catalytic site residues of Ubiquitin

Specific Protease 2 (USP2) by molecular dynamic simulation and

novel kinetics assay for rational drug design. Mol Divers.

27:1323–1332. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Metzig M, Nickles D, Falschlehner C,

Lehmann-Koch J, Straub BK, Roth W and Boutros M: An RNAi screen

identifies USP2 as a factor required for TNF-α-induced NF-κB

signaling. Int J Cancer. 129:607–618. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Shi J, Wang Y, Zeng L, Wu Y, Deng J, Zhang

Q, Lin Y, Li J, Kang T, Tao M, et al: Disrupting the interaction of

BRD4 with diacetylated Twist suppresses tumorigenesis in basal-like

breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 25:210–225. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Peinado H and Cano A: A hypoxic twist in

metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 10:253–254. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Mladinich M, Ruan D and Chan CH: Tackling

cancer stem cells via inhibition of EMT transcription factors. Stem

Cells Int. 2016:52858922016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan

A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al: The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties

of stem cells. Cell. 133:704–715. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Kim JY, Cho TM, Park JM, Park S, Park M,

Nam KD, Ko D, Seo J, Kim S, Jung E, et al: A novel HSP90 inhibitor

SL-145 suppresses metastatic triple-negative breast cancer without

triggering the heat shock response. Oncogene. 41:3289–3297. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Shih YY, Lin HY, Jan HM, Chen YJ, Ong LL,

Yu AL and Lin CH: S-glutathionylation of Hsp90 enhances its

degradation and correlates with favorable prognosis of breast

cancer. Redox Biol. 57:1025012022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Leow CC, Chesebrough J, Coffman KT,

Fazenbaker CA, Gooya J, Weng D, Coats S, Jackson D, Jallal B and

Chang Y: Antitumor efficacy of IPI-504, a selective heat shock

protein 90 inhibitor against human epidermal growth factor receptor

2-positive human xenograft models as a single agent and in

combination with trastuzumab or lapatinib. Mol Cancer Ther.

8:2131–2141. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L and Rosen

N: Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: Combinatorial therapeutic

exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann N Y Acad

Sci. 1113:202–216. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Modi S, Stopeck A, Linden H, Solit D,

Chandarlapaty S, Rosen N, D'Andrea G, Dickler M, Moynahan ME,

Sugarman S, et al: HSP90 inhibition is effective in breast cancer:

A phase II trial of tanespimycin (17-AAG) plus trastuzumab in

patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer progressing on

trastuzumab. Clin Cancer Res. 17:5132–5139. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Sesto N, Wurtzel O, Archambaud C, Sorek R

and Cossart P: The excludon: A new concept in bacterial antisense

RNA-mediated gene regulation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 11:75–82. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Qu X, Alsager S, Zhuo Y and Shan B: HOX

transcript antisense RNA (HOTAIR) in cancer. Cancer Lett.

454:90–97. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Chen SP, Zhu GQ, Xing XX, Wan JL, Cai JL,

Du JX, Song LN, Dai Z and Zhou J: LncRNA USP2-AS1 promotes

hepatocellular carcinoma growth by enhancing YBX1-Mediated HIF1α

protein translation under hypoxia. Front Oncol. 12:8823722022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Pirnia F, Schneider E, Betticher DC and

Borner MM: Mitomycin C induces apoptosis and caspase-8 and −9

processing through a caspase-3 and Fas-independent pathway. Cell

Death Differ. 9:905–914. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Wang WD, Shang Y, Wang C, Ni J, Wang AM,

Li GJ, Su L and Chen SZ: c-FLIP promotes drug resistance in

non-small-cell lung cancer cells via upregulating FoxM1 expression.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 43:2956–2966. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Yang Y, Hou JQ, Qu LY, Wang GQ, Ju HW,

Zhao ZW, Yu ZH and Yang HJ: Differential expression of USP2, USP14

and UBE4A between ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma and adjacent

normal tissues. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 23:504–506.

2007.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Guo B, Yu L, Sun Y, Yao N and Ma L: Long

Non-Coding RNA USP2-AS1 accelerates cell proliferation and

migration in ovarian cancer by sponging miR-520d-3p and

Up-Regulating KIAA1522. Cancer Manag Res. 12:10541–10550. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Li D, Bao J, Yao J and Li J: lncRNA

USP2-AS1 promotes colon cancer progression by modulating Hippo/YAP1

signaling. Am J Transl Res. 12:5670–5682, eCollection 2020.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Tatari N, Khan S, Livingstone J, Zhai K,

McKenna D, Ignatchenko V, Chokshi C, Gwynne WD, Singh M, Revill S,

et al: The proteomic landscape of glioblastoma recurrence reveals

novel and targetable immunoregulatory drivers. Acta Neuropathol.

144:1127–1142. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Ji YR, Cheng CC, Lee AL, Shieh JC, Wu HJ,

Huang AP, Hsu YH and Young TH: Poly (allylguanidine)-coated

surfaces regulate TGF-β in glioblastoma cells to induce apoptosis

via NF-κB Pathway Activation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces.

13:59400–59410. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Joseph JV, Magaut CR, Storevik S, Geraldo

LH, Mathivet T, Latif MA, Rudewicz J, Guyon J, Gambaretti M, Haukas

F, et al: TGF-β promotes microtube formation in glioblastoma

through thrombospondin 1. Neuro Oncol. 24:541–553. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Yan X, Liao H, Cheng M, Shi X, Lin X, Feng

XH and Chen YG: Smad7 protein interacts with receptor-regulated

smads (R-Smads) to inhibit transforming growth factor-β

(TGF-β)/smad signaling. J Biol Chem. 291:382–392. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Girish V, Lakhani AA, Thompson SL, Scaduto

CM, Brown LM, Hagenson RA, Sausville EL, Mendelson BE, Kandikuppa

PK, Lukow DA, et al: Oncogene-like addiction to aneuploidy in human

cancers. Science. Jul 6–2023.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Mejia-Hernandez JO, Raghu D, Caramia F,

Clemons N, Fujihara K, Riseborough T, Teunisse A, Jochemsen AG,

Abrahmsén L, Blandino G, et al: Targeting MDM4 as a novel

therapeutic approach in prostate cancer independent of p53 status.

Cancers (Basel). 14:39472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Tsai KW, Kuo WT and Jeng SY: Tight

junction protein 1 dysfunction contributes to cell motility in

bladder cancer. Anticancer Res. 38:4607–4615. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Chuang SJ, Cheng SC, Tang HC, Sun CY and

Chou CY: 6-Thioguanine is a noncompetitive and slow binding

inhibitor of human deubiquitinating protease USP2. Sci Rep.

8:31022018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Renatus M, Parrado SG, D'Arcy A, Eidhoff

U, Gerhartz B, Hassiepen U, Pierrat B, Riedl R, Vinzenz D,

Worpenberg S and Kroemer M: Structural basis of ubiquitin

recognition by the deubiquitinating protease USP2. Structure.

14:1293–1302. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Kitamura H and Hashimoto M: USP2-Related

cellular signaling and consequent pathophysiological outcomes. Int

J Mol Sci. 22:12092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Graner E, Tang D, Rossi S, Baron A, Migita

T, Weinstein LJ, Lechpammer M, Huesken D, Zimmermann J, Signoretti

S and Loda M: The isopeptidase USP2a regulates the stability of

fatty acid synthase in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 5:253–261.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Cheng JC, Bai A, Beckham TH, Marrison ST,

Yount CL, Young K, Lu P, Bartlett AM, Wu BX, Keane BJ, et al:

Radiation-induced acid ceramidase confers prostate cancer

resistance and tumor relapse. J Clin Invest. 123:4344–4358. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Mizutani N, Inoue M, Omori Y, Ito H,

Tamiya-Koizumi K, Takagi A, Kojima T, Nakamura M, Iwaki S,

Nakatochi M, et al: Increased acid ceramidase expression depends on

upregulation of androgen-dependent deubiquitinases, USP2, in a

human prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP. J Biochem. 158:309–319.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Vieyra-Garcia PA and Wolf P: A deep dive

into UV-based phototherapy: Mechanisms of action and emerging

molecular targets in inflammation and cancer. Pharmacol Ther.

222:1077842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Nakahashi K, Nihira K, Suzuki M, Ishii T,

Masuda K and Mori K: A novel mouse model of cutaneous T-cell

lymphoma revealed the combined effect of mogamulizumab with

psoralen and ultraviolet a therapy. Exp Dermatol. 31:1693–1698.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Hsu J and Sage J: Novel functions for the

transcription factor E2F4 in development and disease. Cell Cycle.

15:3183–3190. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Moghadami AA, Aboutalebi Vand Beilankouhi

E, Kalantary-Charvadeh A, Hamzavi M, Mosayyebi B, Sedghi H,

Ghorbani Haghjo A and Nazari Soltan Ahmad S: Inhibition of USP14

induces ER stress-mediated autophagy without apoptosis in lung

cancer cell line A549. Cell Stress Chaperones. 25:909–917. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Liu C, Chen Z, Ding X, Qiao Y and Li B:

Ubiquitin-specific protease 35 (USP35) mediates cisplatin-induced

apoptosis by stabilizing BIRC3 in non-small cell lung cancer. Lab

Invest. 102:524–533. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Chen J, Dexheimer TS, Ai Y, Liang Q,

Villamil MA, Inglese J, Maloney DJ, Jadhav A, Simeonov A and Zhuang

Z: Selective and cell-active inhibitors of the USP1/UAF1

deubiquitinase complex reverse cisplatin resistance in non-small

cell lung cancer cells. Chem Biol. 18:1390–1400. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

151

|

Zhou F, Du C, Xu D, Lu J, Zhou L, Wu C, Wu

B and Huang J: Knockdown of ubiquitin-specific protease 51

attenuates cisplatin resistance in lung cancer through

ubiquitination of zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox 1. Mol Med

Rep. 22:1382–1390. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Zhang L, Xu B, Qiang Y, Huang H, Wang C,

Li D and Qian J: Overexpression of deubiquitinating enzyme USP28

promoted non-small cell lung cancer growth. J Cell Mol Med.

19:799–805. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Zhang Z, Cui Z, Xie Z, Li C, Xu C, Guo X,

Yu J, Chen T, Facchinetti F, Bohnenberger H, et al: Deubiquitinase

USP5 promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation by

stabilizing cyclin D1. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 10:3995–4011. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Zhu M, Zhang H, Lu F, Wang Z, Wu Y, Chen

H, Fan X, Yin Z and Liang F: USP52 inhibits cell proliferation by

stabilizing PTEN protein in non-small cell lung cancer. Biosci Rep.

41:BSR202104862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Zhang F, Zhao Y and Sun Y: USP2 is an SKP2

deubiquitylase that stabilizes both SKP2 and its substrates. J Biol

Chem. 297:1011092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

156

|

Zhou J, Wang T, Qiu T, Chen Z, Ma X, Zhang