Introduction

Cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases and the

leading cause of death worldwide. The global cancer incidence and

mortality were estimated at nearly 19 million new cases and 10

million deaths in 2020, with lung, colorectal, breast and prostate

cancer accounting for the majority of the diagnosed cancers

worldwide (1,2). Despite the increasing survival rates

of cancer patients observed in the past decades due to improved and

game-changing therapies, the global incidence of cancer keeps

increasing and is estimated to reach 28 million per year in 2040,

leading to a physical, emotional and financial burden to the

patients and their families, and a strain on resources of the

public health system (2,3). The cancer burden has been attributed

to the inequitable access to cancer prevention, early detection,

screening and treatment of the population, particularly in low- and

middle-income countries. In addition, an increase in the price of

cancer drugs has been recorded in recent years. Cancer is predicted

to cost $25.2 trillion to the world economy from 2020 to 2050,

bringing severe financial distress to the economy, affected

patients and families, and the public health system (4,5).

Furthermore, highly effective treatments, including radiotherapy,

chemotherapy, surgery, targeted therapy and hormonal treatments,

which significantly contribute to the overall reduction of cancer

mortality, recurrence and spread and increase in survival rate,

have limitations in curing cancer, particularly in patients with

delayed diagnoses and in patients with cancer therapy resistance,

resulting in a worse survival outcome (6,7).

Drug repositioning, an approach to using approved

drugs to treat diseases outside their original indication scope,

has gained significant attention in recent years (8). Repurposing existing drugs reduces the

exorbitant cost of developing new drugs, estimated to be between

$314 million and $2.8 billion per medication in 2018. It shortens

the time taken for the drug approval process, which can otherwise

take 10 to 15 years to reach the market (8,9).

Furthermore, repurposed drugs have a decreased likelihood of

clinical failure due to adverse effects, as their safety and dosing

have already received clinical approval (10). Consequently, repurposing drugs for

cancer treatment represents a cost-effective method for cancer

therapy.

Various antipsychotic drugs including penfluridol

(PF), phenothiazine, pimozide, chlorpromazine and thioridazine have

been discovered to have anticancer properties and have been

identified as a promising alternative cancer treatment (11). Several studies have reported that

patients taking antipsychotic drugs have a lower cancer incidence

compared to the general population (12). PF is a well-established

first-generation diphenylbutylpiperidine (DPBP) antipsychotic drug

used to treat chronic schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders,

and has been found to inhibit cancer (11,13).

Indeed, PF inhibits cancer cell proliferation and induces apoptosis

and autophagy in various cancer cell lines (14). PF has a half-life of 70 h, can cross

the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and block the dopamine receptor

(DRD2) binding sites, making it a potent drug for the treatment of

brain cancers, as well as cancers with high brain metastasis

ability (13,15,16).

This scoping review aimed to briefly investigate the anticancer

properties of PF, focusing on in vivo and in vitro

studies and providing a concise overview of PF's anticancer

mechanism of action.

Methodology

Protocol

This scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for

Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist and PRISMA-ScR Tip sheets

(17). The review was conducted in

five stages according to Mak and Thomas's (18) steps for conducting a scoping review:

i) Identify the research question; ii) identify relevant studies;

iii) select the studies to be included in the review; iv) charting

data; and v) collate, summarize and report results.

Identification of the research

question

This review aimed to investigate the effect of PF on

cancer. Following the standard recommendation for a broader

research question (19), a primary

research question was developed: What are the effects of PF on

cancer? This research question provided sufficient literature to

warrant the scoping review and envelop the studies on PF as a

treatment for cancer. Hence, no further narrowing of the research

question was necessary.

Identification of relevant

studies

A literature search was conducted using the Scopus

(https://www-scopus-com.uitm.idm.oclc.org), PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Web

of Science (WoS; http://www-webofscience-com.uitm.idm.oclc.org)

databases with the search string ‘penfluridol’ AND ‘cancer’. The

search, conducted in November 2023, included no additional

filters.

Study selection

Following the search, the identified records were

assessed in two phases. In the first phase, one author (AAIM)

evaluated the obtained articles by their titles and excluded

duplicate articles, review papers and retracted papers. The same

author screened the remaining journal papers based on their titles

and abstracts. Any articles with no relation to the roles of PF in

treating cancers according to their titles and abstracts and any

conference abstracts were excluded. In the second phase, one author

(AAIM) retrieved and assessed the remaining articles' full text. In

the end, original research articles on the roles, functions,

importance and mechanisms of PF in treating cancer written in

English were retained and included in the scoping review. The

second author (AAR) was consulted for their opinion on the obtained

data throughout the study selection stages.

Mendeley Desktop version 1.19.8 (Elsevier) and

Microsoft Excel version 16.89.1 (Microsoft Corporation) were used

to sort out the literature and identify the articles' duplication

by independently filtering out the articles' DOIs, titles and

abstracts.

Charting the data

Microsoft Excel version 16.89.1 (Microsoft

Corporation) was used to organize the data from the selected

articles. Data extraction was performed following the PRISMA

guidelines by (AAIM). The extracted data were categorised into

author names, publication year, type of cancer, dose of PF, study

design, significant findings, key findings and limitations.

Collating, summarizing and reporting

of the results

The extracted data were tabulated in Microsoft Excel

version 16.89.1 (Microsoft Corporation) with rows relating to the

articles and columns that classify the variables and contain the

relevant information. This table was used to classify and report

the information collected.

Results

Article selection

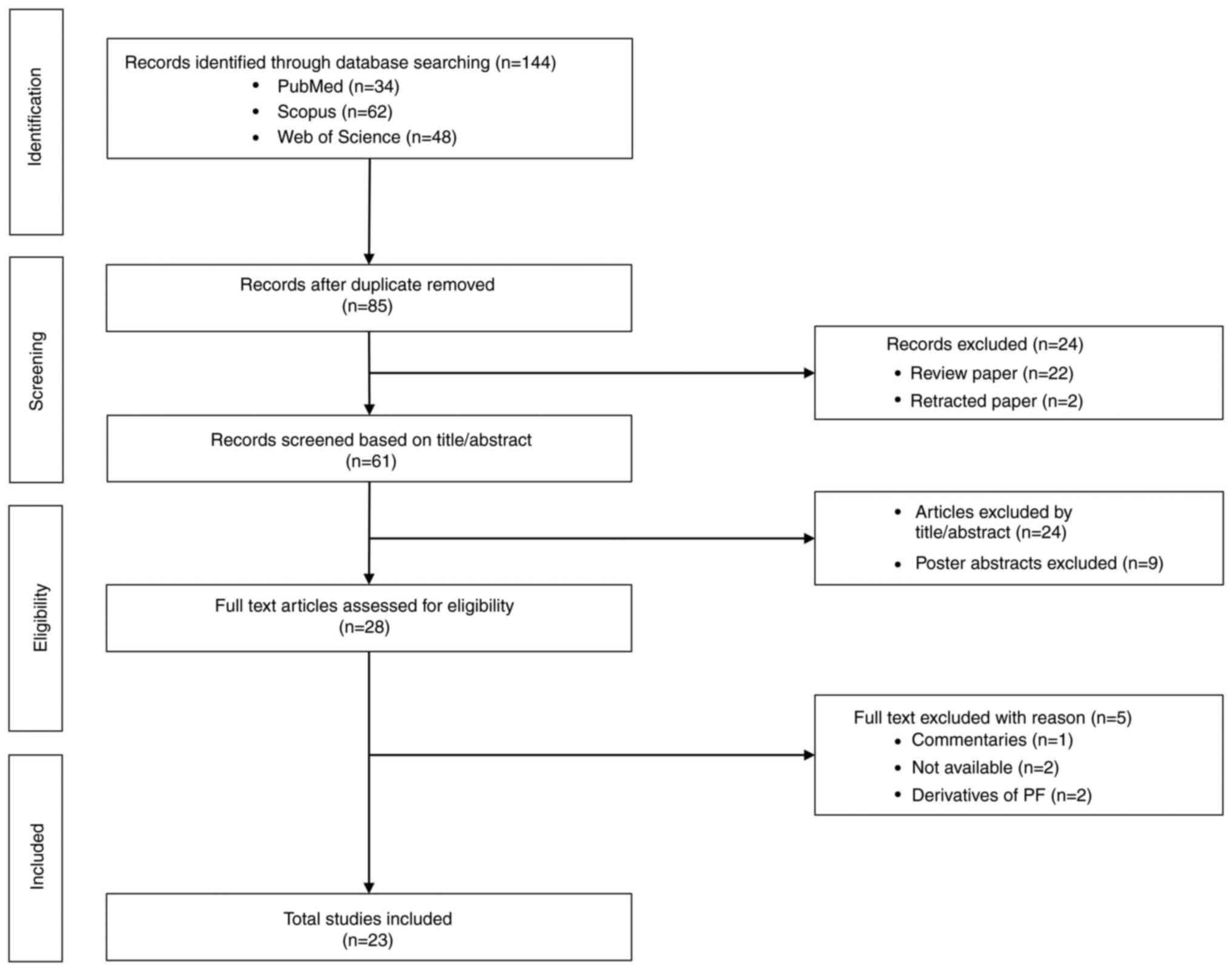

The primary search yielded 144 articles, 34 from

PubMed, 62 from Scopus and 48 from WoS. A total of 59 duplicates

were removed, resulting in 85 records retained and screened

further. Subsequently, a total of 24 articles were eliminated due

to being reviews (n=22) and retracted papers (n=2). The remaining

61 articles were screened based on title and abstract and 24

articles with no relation to the roles of PF in treating cancers

and poster abstracts (n=9) were excluded. A total of 28 records

were identified as eligible for further full-text assessment. Of

the 28 articles, five were excluded due to lack of availability

(n=2), focusing on PF derivatives (n=2) and commentaries (n=1).

Finally, 23 original research studies in English were retained for

this scoping review. The PRISMA flowchart on the paper selection is

presented in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The main findings are summarised and presented in

Table I. Out of the 23 original

articles included in this review, 4 evaluated the anticancer effect

of PF on breast cancer, 4 on lung cancer, 4 on pancreatic cancer, 3

on glioblastoma, 1 on bladder cancer, 1 on gallbladder cancer, 1 on

oesophageal cancer, 1 on leukaemia cancer and 1 on renal cancer.

The remaining 3 articles included in this review studied the effect

of PF on various types of cancer. All of the studies in this review

included an in vitro model of a cell line supplemented with

0 to 40 µM PF, while most studies used an in vivo model

treated with PF at 1 to 10 mg/kg.

| Table I.The effect of penfluridol on

cancer. |

Table I.

The effect of penfluridol on

cancer.

| Type of cancer | Author(s),

year | Study model | Doses | Treatment

duration | Findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Breast | Hedrick | SKBR3 & | 0.7–7.5 µM | 24 h | PF inhibited cell

growth and cell migration and | (20) |

|

| et al

2017 | MDA-MB- |

|

| induced cell

apoptosis. PF induced ROS in breast |

|

|

|

| 231 cells |

|

| cancer cells by

downregulating the expression of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sp transcript

factor (Sp1, Sp2 and Sp4) and cMyc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (miR-27a and

miR-20/miR-17). PF repressed the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| expression of α5-,

α6-, β1 and β4-integrin. |

|

|

|

| Female | 10 mg/kg/ | 19 days | PF decreased the

tumour volume, inhibited tumour |

|

|

|

| athymic | day |

| growth and induced

apoptosis. PF ROS-dependently |

|

|

|

| nude mice |

|

| reduced the

expression of Sp1, Sp3, Sp4 and Sp- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| regulated genes

(α6-, α5-, β1- and β4-integrins). |

|

|

| Gupta | MCF-7, | 0-20 µM | 24-72 h | PF treatment

inhibited the cell growth and colony | (21) |

|

| et al

2019 | MCF-7HH, |

|

| formation of

PXT-sensitive and PXT-resistant cells |

|

|

|

| MCF-7PR, |

|

| in a concentration-

and time-dependent manner. PF |

|

|

|

| 4T1 &

4T1PR |

|

| downregulated the

expression of HER2, β-catenin, |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| c-Myc, TCF-1,

TCF-4, p-GSK3β and cyclin D1. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| induced apoptosis

in breast cancer cells. A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| combination of PXT

and PF significantly reduced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the cancer cells'

viability, suppressing the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| chemoresistance

markers while enhancing apoptosis. |

|

|

|

| Female | 10 mg/kg/ | 23 days | PF significantly

suppressed the growth of paclitaxel- |

|

|

|

| Balb/c mice | day |

| resistant cells

alone or in combination with 5 mg/kg/3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| days PXT. PF alone

and PF combined with PXT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| inhibited HER2 and

β-catenin expression and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| increased

apoptosis. |

|

|

| Ranjan | MDA-MB- | 0-20 µmol/l | 24-72 h | PF suppressed the

proliferation, migration and | (22) |

|

| et al

2016 | 231, 4T1 & |

|

| invasion of breast

cancer. PF treatment inhibited |

|

|

|

| HCC1806 |

|

| cells' survival and

motility by reducing the |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| expression of

integrin α6, integrin β4, FAK, paxillin, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rac1/2/3 and ROCK1

and inducing apoptosis. |

|

|

|

| Female Balb/ | 10 mg/kg | 27 days | PF suppressed

tumour growth by inhibiting |

|

|

|

| c mice |

|

| β4-integrin and

enhancing apoptosis in mice. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Intracardiac or

intracranial injection of breast cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| cells revealed

similar results. |

|

|

| Srivastava | HUVECs & | 0-5 µM | 24-48 h | Low doses of PF

blocked the angiogenesis- | (23) |

|

| et al

2020 | MDA-MB-23 |

|

| suppressed

VEGF-induced primary endothelial cell |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| migration and tube

formation of the cancer cells. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| inhibited the Src

and Akt signalling pathways. |

|

|

|

| C57B/L6 | 1 mg/kg | 11 days | Low dose of PF

blocked VEGF- and FGF-induced |

|

|

|

| mice |

|

| angiogenesis. |

|

| Lung | Lai et

al | A549 & | 0-7.5 µM | 24 h | PF inhibited lung

tumour growth by reducing | (24) |

|

| 2022 | HCC827 |

|

| mitochondrial ATP

production and downregulating |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| NADH levels. PF

mediated the suppression of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| mitochondrial

biogenesis, impeded the level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of PGC-1α protein

and mRNA, SIRT1 and p53, and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| induces AMPK

activation. |

|

|

|

| NOD-SCID | 5 m/kg | 28 days | PF inhibited the

growth and metastasis of lung |

|

|

|

| mice |

|

| cancer in mice.

These results were enhanced in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| combination with

2DG. PF decreased the expression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of PGC-1α and

SIRT1. |

|

|

| Xue et

al | A549, H446, | 0-20 µM | 24-72 h | PF inhibited lung

cancer cell growth and viability | (26) |

|

| 2020 | H1993, |

|

| with G0/G1 cell

cycle phase arrest by enhancing the |

|

|

|

| SPC-A1 & |

|

| expression level of

p21/p27 and decreasing the |

|

|

|

| LL2 cells |

|

| expression levels

of the cyclin-CDK complex. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| induced apoptosis

via the mitochondria-mediated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| intrinsic apoptosis

pathway and inhibited the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| migration and

invasion of lung cancer cells. |

|

|

|

| Female | 10 mg/kg | 26 days | PF inhibited tumour

growth in an A549 cell |

|

|

|

| Balb/c |

|

| xenograft mouse

model. PF blocked the proliferation |

|

|

|

| nude mice |

|

| and metastasis of

lung cancer in mice by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| regulating the AKT

and MMP signalling pathways |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| while inducing

apoptosis. |

|

|

| Hung | NSCLC, | 7.5–10 µM | 24-72 h | PF suppressed cell

proliferation by inducing ER | (25) |

|

| et al

2019 | A549, |

|

| stress- mediated

autophagosome accumulation to |

|

|

|

| HCC827 & |

|

| deplete ATP energy.

PF inhibited cell migration. |

|

|

|

| BEAS-2B |

|

| PF induced

nonapoptotic cell death by blocking |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| autophagic flux and

autophagosome formation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of LC3B-II protein

in lung cancer cells. |

|

|

|

| NOD-SCID | 5-10 mg/kg | 35 days | PF inhibited the

growth and the metastasis of lung |

|

|

|

| mice |

|

| cancer in mice by

inducing an accumulation of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

autophagosome-related protein. |

|

|

| Hung | A549, H23, | 0-20 µM | 24-72 h | PF reduced the

migration, invasion and adhesion | (27) |

|

| et al

2021 | HCC827, |

|

| of LADC cells. PF

inhibited MMP-12 by |

|

|

|

| PC9, H1975, |

|

| downregulating the

uPA/uPAR/TGF-β/Akt axis to |

|

|

|

| HMEC-1 & |

|

| modulate the

motility and adhesion of LADC cells. |

|

|

|

| BEAS-2B |

|

| PF inhibited EMT

byupregulating E-cadherin and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| downregulating

N-cadherin. |

|

|

|

| Male NOD- | 2.5 µM | 5 weeks | PF suppressed lung

metastasis and colony formation. |

|

|

|

| SCID mice |

|

| PF increased the

expression of E-cadherin levels and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| decreased

N-cadherin and MMP-12 levels in tumour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| tissues. |

|

| Pancreatic | Ranjan | AsPC-1, | 0-10 µM | 24-72 h | PF induced ER

stress in pancreatic cancer cells | (28) |

|

| et al

2017 | BxPC-3 & |

|

| characterised by

the upregulation of ER stress |

|

|

|

| Panc-1 cells |

|

| markers of BIP,

CHOP and IRE1α. PF-induced ER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| stress led to

autophagy. |

|

|

|

| Female | 10 mg/kg | 3 weeks | PF-treated mice had

a high level of BIP, CHOP |

|

|

|

| athymic |

|

| and IRE1α

expression in the tumour lysates and a |

|

|

|

| nude mice |

|

| reduction of tumour

mass. |

|

|

| Ranjan and | BxPC-3 & | 0-20 µM | 24-72 h | PF induced

apoptosis and inhibited the growth of | (29) |

|

| Srivastava | AsPC-1 |

|

| pancreatic cancer

cells. PF enhanced autophagy in |

|

|

| 2016 |

|

|

| pancreatic cancer

cells mediated by apoptosis. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| impeded the

formation of lysosomes. |

|

|

|

| Female | 10 mg/kg | 27 & 59 | PF reduced the

growth of BxPC-3 tumour xenografts |

|

|

|

| athymic |

| days | and the development

of orthotopically implanted |

|

|

|

| nude mice |

|

| pancreatic tumours

by 80% by inducing autophagy- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| mediated apoptosis

in the tumours. |

|

|

| Dandawate | AsPC-1, | 0-40 µM | 24-72 h | PF highly bound to

the JAK2 domain PRLR. PF | (30) |

|

| et al

2020 | BxPC-3, |

|

| suppresses

pancreatic cancer cells' proliferation and |

|

|

|

| Panc-1, |

|

| colony and spheroid

formation. PF enhanced PDAC |

|

|

|

| MiaPaCa-2,

& |

|

| autophagy. The PF

mechanism of inhibition of |

|

|

|

| UNKC-6141 |

|

| PDAC cell growth

did not proceed through DRD2. |

|

|

|

| Male C57BL/6 | 5 mg/kg | 28 & 35 | PF decreased the

weight of the orthotopic tumours. |

|

|

|

|

|

| days | PF significantly

inhibited the tumour weight and |

|

|

|

| mice &

PDX- |

|

| volume in xenograft

tumours. PF reduced PDAC |

|

|

|

| carrying |

|

| tumour growth by

inducing autophagy. |

|

|

|

| NGS mice |

|

|

|

|

|

| Chien | Panc0403, | 0-10 µM | 0-36 h | PF inhibited

pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and | (31) |

|

| et al

2015 | SU8686, |

|

| growth and induced

apoptosis. PF decreased the |

|

|

|

| MiaPaCa2, |

|

| phosphorylation

levels of SRC, AKT and p70S6K. |

|

|

|

| Panc1, |

|

| PF induced the

activation of PP2A protein |

|

|

|

| Panc0504, |

|

| phosphatase leading

to pancreatic cancer cell death. |

|

|

|

| AsPc1, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Panc1005, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Panc0203, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Panc0327, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BxPc3 & |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HPDE |

|

|

|

|

| Glioblastoma | Ranjan and | GBM43, | 0-20 µM | 24-72 h | PF reduced the

survival rate and induced apoptosis | (32) |

|

| Srivastava | GBM10, |

|

| in glioblastoma

cell lines. PF treatment suppressed |

|

|

| 2017 | GBM44, |

|

| the phosphorylation

of Akt at Ser473 and decreased |

|

|

|

| GBM28, |

|

| the expression of

GLI1, OCT4, Nanog and Sox2. |

|

|

|

| GBM14 & |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U251MG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Athymic nude | 10 mg/ | 39-54 | PF treatment

inhibited the growth and reduced the |

|

|

|

| mice | kg/day |

| volume of days

in vivo glioblastoma tumour models. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PF reduced pAkt,

GL1 and OCT4 and enhanced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| apoptosis. |

|

|

| Kim et

al | CSC2, X01, | 0-20 µM | 24-72 h | PF suppressed the

growth of GSCs in a dose- and | (33) |

|

| 2019 | 0315, 528NS, |

|

| time- dependent

manner. PF suppressed the stemness |

|

|

|

| 83NS, U87MG |

|

| of GSCs and

inhibited their sphere-forming ability |

|

|

|

| & T98G

cells |

|

| and invasiveness.

PF inhibited the EMT potential |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| in human GSCs. |

|

|

|

| Female Balb/c | 0.8 | 60 days | PF decreased

invasion and tumour volume in |

|

|

|

| nude mice | mg/kg/ |

| orthotopic

xenografts by reducing GLI1, uPAR, |

|

|

|

|

| week |

| SOX2 and vimentin

expression. With a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| combination of PF

and TMZ, the tumour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| disappeared in the

mice. |

|

|

| Ranjan | Female | 10 mg/kg | 40-48 | PF treatment

suppressed glioblastoma tumour | (34) |

|

| et al

2017 | athymic |

| days | growth by reducing

murine myeloid-derived |

|

|

|

| nude mice

& |

|

| suppressor cells

(MDSC). PF enhanced splenic cell |

|

|

|

| female SCID- |

|

| proliferation,

increased M1 macrophages and |

|

|

|

| NOD mice |

|

| suppressed

T-regulatory cells and inflammation in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the tumour. |

|

| Gallbladder | Hu et

al | EH-GB1, | 0-10 µM | 24-72 h | PF inhibited the

proliferation and migration of | (35) |

|

| 2022 | GBC-SD & |

|

| gallbladder cancer

(GBC) cells and enhanced |

|

|

|

| SGC-996 |

|

| apoptosis. PF

treatment caused the activation |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| of

AMPK/PFKB3-mediated glycolysis in GBCs, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| and a combination

of PF and 2-DG or AMPK |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| inhibitor CC

improved the anticancer effect of PF. |

|

|

|

| Old female | 10 mg/kg | 15 days | PF suppressed lung

tumour growth. PF promoted |

|

|

|

| nude mice |

|

| apoptosis and the

activation of AMPK/PFKFB3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| signaling. |

|

| Bladder | van der | UCB & | 0-100 µM | 0-40 h | PF inhibited the

cell viability and clonogenicity | (36) |

|

| Horst et

al | UM-UC- |

|

| of the UCB cell

line. PF induced lysosomal |

|

|

| 2020 | 3luc2 cells |

|

| leakage and

destabilized lysosomal structures in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| human UCB cells,

resulting in the redistribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of

phosphatidylserine from the internal to the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| external membrane

surface, an early indicator |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| of apoptosis. |

|

|

|

| Female Balb/c | 130 µg/kg | 29 days | PF significantly

decreased tumour growth, |

|

|

|

| nude mice | per week |

| invasion and

metastasis in mice. |

|

| Oesophageal | Zheng | KYSE30, | 0-10 µmol/l | 24-72 h | PF inhibited

proliferation and colony formation | (37) |

|

| et al

2020 | KYSE150 & |

|

| and enhanced the

apoptosis of the esophageal |

|

|

|

| KYDEE270 |

|

| squamous cell

carcinoma (ESCC) cells. The |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| inhibition of the

cells was mediated by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AMPK/FOXO3a/BIM

signalling. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| inhibited

glycolysis. |

|

|

|

| Female Balb/c | 9-18 mg/kg | 42 days | PF decreased tumour

volume and cell |

|

|

|

| nude mice |

|

| proliferation and

induced apoptosis in tumour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| xenograft mice. PF

inhibited glycolysis. |

|

| Leukaemia | Wu et

al | HL-60, U937 | 7.5–20 µM | 24-72 h | PF inhibited the

proliferation of AML cells. | (38) |

|

| 2019 | & MV4-11 |

|

| PF induced

apoptosis by activating PP2A to |

|

|

|

| cell lines |

|

| suppress Akt and

MAPK activities. PF |

|

|

|

| with FLT3-WT |

|

| triggered

autophagic responses by inducing |

|

|

|

| or FLT3-ITD |

|

| the elevation of

intracellular ROS levels. |

|

| Renal | Tung | 786-O, | 0-25 µM | 24-72 h | PF decreased the

proliferation and colony | (39) |

|

| et al

2022 | Caki-1, A498 |

|

| formation of RCC

cells. PF induced autophagy |

|

|

|

| & ACHN

cells |

|

| through the ER

stress-mediated UPR, leading |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| to apoptosis. PF

reduced stemness and sphere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| formation in RCC

cells. |

|

|

|

| NOD-scid | 5 µM | 5 weeks | PF reduced the

tumour volume and growth by |

|

|

|

| IL2Rγ |

|

| suppressing the

GLI1 and proliferation |

|

|

|

| (NSG) mice |

|

| index Ki-67. |

|

| Diverse | Wu et

al | B16, LL/2, | 0-9 µmol/l | 24-72 h | PF inhibited the

proliferation of melanoma, | (40) |

|

| 2014 | CT26 & |

|

| lung carcinoma,

colon carcinoma and breast |

|

|

|

| 4T1 cells |

|

| cancer cells in a

time-dependent manner. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| increased the

accumulation of unesterified |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| cholesterol in the

cancer cells. |

|

|

|

| Female | 0.06–0.12 mg/ | 45 days | PF suppressed lung,

colon, melanoma and |

|

|

|

| C57BL/6 | week |

| breast tumour

growth, and tumour weight of |

|

|

|

| mice & |

|

| the mice. PF

decreased the total cholesterol |

|

|

|

| Balb/c mice |

|

| in the tumour

tissue of the mice. |

|

|

| Varalda | HCT116, | 10-160 µmol/l | 24-72 h | PF inhibited the

proliferation of colorectal | (14) |

|

| et al

2020 | SW620, |

|

| and breast cancer

and glioblastoma cells. |

|

|

|

| MCF7, MDA- |

|

| PF reduced MCF7 and

HCT116 cell motility |

|

|

|

| MB-231, |

|

| and migration. PF

induced mitochondrial |

|

|

|

| U87 & U251 |

|

| and lysosomal

membrane alteration and |

|

|

|

| cells |

|

| phospholipid

aggregation in cancer cells. PF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| suppressed the mTOR

pathway, induced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| by AMPK activation

and autophagy. |

|

|

| Du et

al | HeLa | 5 µmol/l | 24 h | PF has high

radiosensitivity activity. PF | (41) |

|

| 2018 |

|

|

| inhibited the

repair of DSBs post-IR in HeLa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| cells by reducing

NHEJ repair and preventing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| the activation of

DNA-PKcs. |

|

Synthesis of the results

Breast cancer

PF was found to exert its anticancer properties on

breast cancer through multiple pathways. PF inhibits cell

proliferation in breast cancer cells (20–23).

For instance, in the relevant studies, PF successfully reduced the

tumour volume and weight in the in vivo model of breast

cancer. Furthermore, PF was found to reduce cell migration through

reactive oxygen species (ROS) (20), the integrin pathway (22) and the VEGF pathway (23). In addition, PF was capable of

inducing apoptosis in breast cancer cells (20–22).

While Hedrick et al (20)

imparted that the anticancer properties of PF in breast cancer are

ROS-dependent, Gupta et al (21) revealed that PF downregulates the

expression of chemoresistance markers in paclitaxel (PXT)-resistant

breast cancer, leading to apoptosis. In fact, cotreatment of PF

with glutathione attenuated the effect of PF on breast cancer

(20), and the combination of PF

and PXT decreased the expression of human EGFR 2 (HER2), β-catenin

and cyclin D, simultaneously enhancing apoptosis (21). It is worth mentioning that chronic

administration of PF failed to elicit any significant toxic or

behavioural side effects in mice (22) and that low concentrations of PF can

block angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo (23).

Lung cancer

Studies on PF in the treatment of lung cancer

revealed that PF inhibits lung tumour growth by inducing

mitochondrial ATP energy loss in vivo and in vitro

(24). Similar results were

obtained pertaining to autophagy (25). PF inhibited lung cancer

proliferation, migration and metastasis in vivo and in

vitro by regulating the AKT and MMP signalling pathway

(26,27). PF suppressed MMPs and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) required for cancer cell

motility and adhesion (27).

Induced G0/G1 phase arrest, ROS and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

stress, as well as loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential

(ΔΨm), were noted in PF-treated lung cancer (25,26).

On the other hand, PF in combination with glycolysis inhibitor

2-deoxy-D-glucose synergistically enhanced the inhibitory effect of

PF on lung cancer cell growth and the total amount of mitochondria

(24). No side effects were noted

in the mice used in these studies.

Pancreatic cancer

In pancreatic cancer, PF was reported to induce

autophagy (28–30) and apoptosis (29,31) in

in vitro and in vivo models. PF inhibited the

proliferation and colony formation of pancreatic cancer cells

(28–31) through the suppression of prolactin

receptor (PRLR) signalling (30)

and the activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) protein

phosphatase (31). A study by

Ranjan & Srivastava (29)

revealed that PF induced autophagy-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic

cancer. However, while PF exerts its antipsychotic activity by

blocking the DRD2 receptors, the antiproliferative activity of PF

in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is not related to DRD2 and does

not trigger protein degradation (30).

Glioblastoma

In glioblastoma, PF appeared to reduce the growth of

glioblastoma cells and a tumour model through the apoptosis pathway

(32). In addition, GLA1 was

downregulated in a glioblastoma cancer model treated with PF

(32,33). On the other hand, Ranjan et

al (34) showed that PF

treatment suppresses glioblastoma growth through immune regulation,

while Kim et al (33)

denoted that it is by reducing the sphere formation, stemness and

invasiveness of the cells. Of note, a combination of PF and

temozolomide (TMZ) produced maximal antiproliferative and antitumor

effects in in vivo and in vitro models (33).

Other cancers

PF inhibited the cell proliferation and colony

formation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) cells

(37), renal cell carcinoma (RCC)

cell lines (39), acute myeloid

leukaemia (AML) cells (38),

gallbladder cancer (35), bladder

cancer (36), colorectal and breast

cancer, glioblastomas, lung cancer and melanoma cells (14,40).

For instance, PF reduces glycolysis and promotes cell apoptosis

(35,36). Apoptosis was induced in cancer cells

through repressed glycolysis (37)

and activation of PP2A (38) in

ESCC and AML cells, respectively. Combining 2-deoxy-D-glucose

(2-DG) or AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) inhibitor Compound C

(CC) significantly improved PF's anticancer effect in gallbladder

cancer (35). Furthermore, PF

enhanced autophagy in cancer cells by upregulating ER stress and

ROS (38,39). It is worth highlighting that the

anticancer activities of PF on RCC partially occurred through DRD2

(39) and that PF suppresses the

mTOR pathway in various cell lines (14). Besides that, in vivo studies

uncovered that PF effectively prolongs the survival rate of mice

bearing lung tumours and enhances the decrease of total cholesterol

in tumour tissues with no significant difference in the serum

cholesterol levels of the PF-treated mice (40). No side effects to the vital organs

of the PF-treated mice were noted despite the decrease in tumour

growth and volume in vivo (37,39).

In addition, PF-treated urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (UCB)

orthotopic xenograft mice exhibited normal murine urothelium,

epithelial tissue integrity, proliferation index (proliferating

cell nuclear antigen), viable epithelial cell numbers and

fragmented keratin (36). In the

meantime, extensive research by Du et al (41) unveiled that PF has high

radiosensitizing activity and can suppress the activity of

non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).

Discussion

PF

PF

{4-(4-chloro-α,α,α,-trifluoro-m-tolyl)-1-[4,4-bis-(p-fluorophenyl)-butyl]-4-piperidinol}

is a DPBP, first-generation antipsychotic drug used to treat

chronic schizophrenia, Tourette's syndrome, acute psychosis and

other psychotic disorders discovered by Janssen Pharmaceutical in

1968 (15,42,43).

PF is a long-lasting neuroleptics drug orally administered once a

week with a half-life of 66 h and a terminal plasma half-life of

199 h (44). Indeed, PF is highly

lipophilic and is deposited in the adipose tissue after absorption

in the gastrointestinal tract, which heightens its prolonged

duration of action, since PF is gradually released from these

reservoirs (15,44). PF is excreted via urine and faeces

(45). The maximal weekly dose of

PF treatment for patients with chronic schizophrenia varies between

60 and 140 mg (46,47). According to Andrade (48), long half-life antipsychotic drugs

significantly reduce the withdrawal or discontinuation syndrome of

the drug but can be disadvantageous in case of toxicity or side

effects. For instance, PF treatment fosters various adverse

effects, including depression, agitation, drowsiness, tachycardia,

hypotension, insomnia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (49). Therefore, a low dose of PF treatment

is recommended.

PF is capable of penetrating the BBB, making it a

promising option for the treatment of brain-metastasized cancers

(33). Airoldi et al

(43) revealed that despite the

distribution of PF in the adipose tissue being higher, PF remains

concentrated in the brain with the highest concentration recorded

in the hemisphere part of the brain 1 h after the injection and the

mesencephalon 24 h after the injection of 0.5 mg/kg PF in rats. PF

acts by blocking the dopamine receptor, particularly DRD2, where it

binds with a high affinity, leading to the inhibition of

dopaminergic neurotransmission (13,15,16). A

former study by Enyeart et al (50) revealed that the PF also blocks the

T-type and L-type calcium channels at low concentrations.

Additionally, Vlachos et al (12) have reported that patients taking

antipsychotic drugs have a lower cancer incidence compared to the

general population (12).

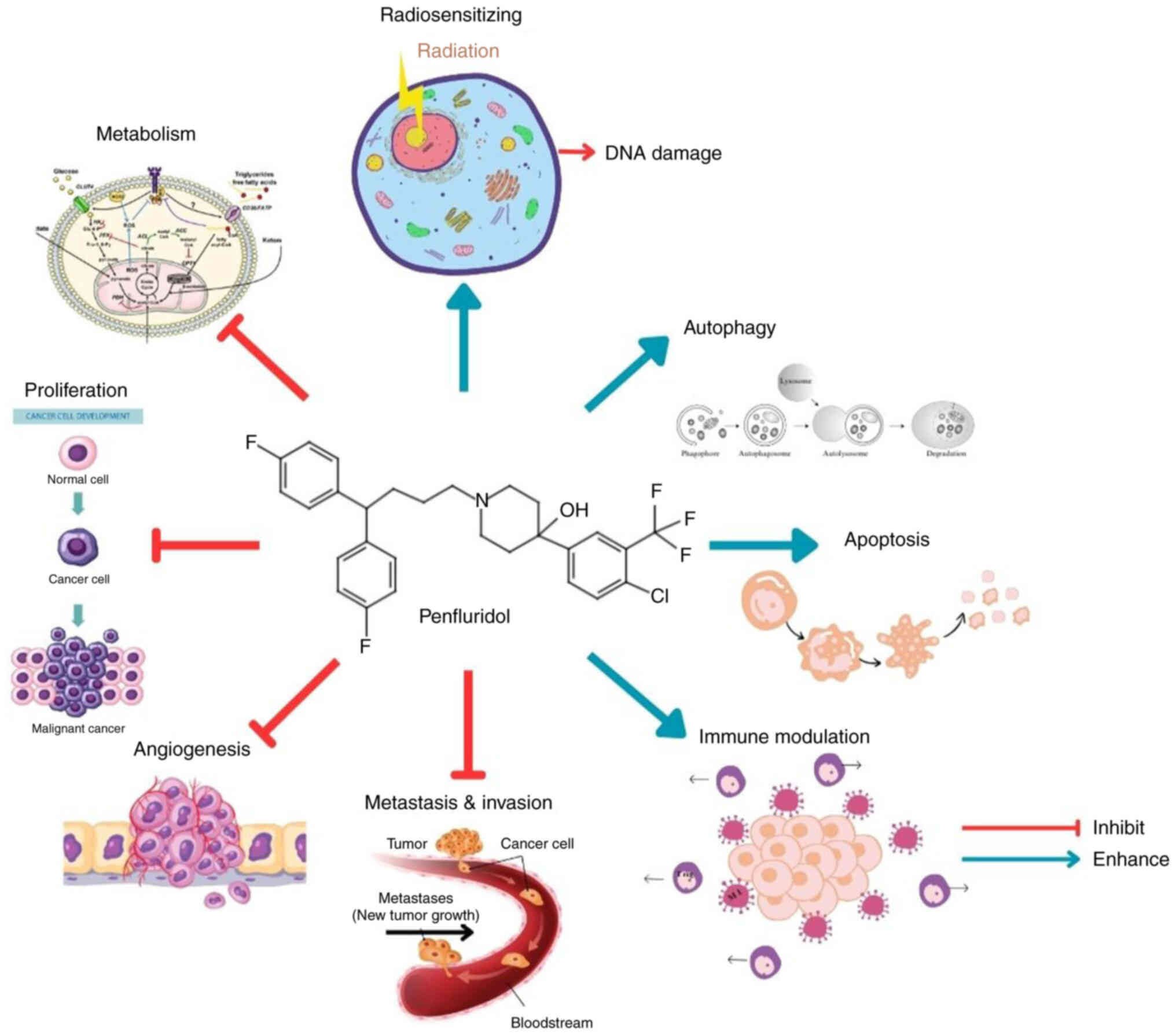

Henceforth, examining the anticancer properties of PF may offer

valuable insight. Fig. 2 summarises

the anticancer activities of PF.

The anticancer properties of PF

PF was found to inhibit cell proliferation in a

dose- and time-dependent manner in all the cancer cells reported in

this review (14,20–41).

For instance, <10 µmol/l of PF induced 50% cell death in various

cancer cell lines (14), while

<2.5 µM of PF inhibited the proliferation and colony formation

of lung and renal cancer cells (25,39).

Meanwhile, 0.12 mg/week of PF remarkably prolonged the survival

time in the LL/2 in vivo cancer model (40), indicating that a low concentration

of PF can provide anticancer properties. The antiproliferative

effects of PF are not mediated by major neuroreceptor systems

(14), but instead by interfering

with the mechanism involved in cancer growth. Indeed, PF induced

cell death by downregulating the cell growth proteins (cyclin D and

MYC) and expression of the G2-M phase of cell cycle arrest protein

cyclin B1 and p21 in pancreatic cells (31). The regulatory protein of the

transition between the G2 to M phase has a significant role in the

proliferation of the tumour and inhibition of these proteins led to

cell-cycle arrest and eventually apoptosis (51,52).

In addition, PF activates PP2A, mediating apoptosis and cell death

(31,38). PP2A is a positive regulator of

apoptosis and activation of PP2A dephosphosphorylates and

inactivates anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, inducing apoptosis (53).

On the other hand, PF increased ROS levels in lung

cancer cells, leading to cell death (26). ROS functions as a double-edged sword

in cancer cells and can act as a tumour-promoting or suppressing

agent (54,55). Cancer cells possess elevated levels

of ROS in comparison to normal cells due to their fast

proliferation and alteration in cellular metabolism, particularly

the reprogrammed metabolism to aerobic glycolysis (56,57).

Moderate levels of ROS are necessary for cancer cell proliferation,

invasion, migration and angiogenesis, while excessively elevated

ROS increase cancer cell damage and death (58,59).

Indeed, PF induced ROS production triggering autophagy in AML cells

(38). Furthermore, Hedrick et

al (20) revealed that PF

enhances ROS production, leading to the downregulation of cMyc

expression and decreased expression of Sp1, Sp3, Sp4 and

Sp-regulated genes in vitro and in an in vivo model

of breast cancer, hence inhibiting cell viability and inducing

apoptosis. The specificity proteins Sp and the multifaceted

oncogene c-Myc are essential regulators of cellular proliferation,

metabolism, metastasis and apoptosis, which, when upregulated,

conduce to the progression of cancer (60–63).

Furthermore, Sp regulates the activation or repression of

integrins, transmembrane receptors which partake in cancer

development, progression, invasion, metastasis and resistance to

therapy (64–67). Ranjan et al (22) showed that PF reduced the expression

of α6, α4, αv, β4, β1 and β3 integrins, as well as the downstream

effector molecules of integrin signalling, including focal adhesion

kinase (FAK), phosphorylated paxillin and paxillin in breast cancer

(22). Desgrosellier & Cheresh

(68) revealed that integrin

signalling plays a significant role in cancer migration,

proliferation and invasion and inhibition of integrins lead to the

repression of tumour invasion and growth.

Apart from that, PF enhances energy loss. For

instance, according to Lai et al (24), PF inhibits non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC) cell growth by increasing ATP energy loss through

the suppression of mitochondrial ATP production activity and

biogenesis. Similarly, suppression of ATP increased the formation

and accumulation of autophagosomes in NSCLC, leading to death

(25). Indeed, cancer cells require

a considerable energy supply for their metabolism (69). This phenomenon known as the Warburg

effect is marked by an elevated glycolysis in the cancer cells,

including aerobic glycolysis to meet the energy needs of the cells

to grow (70). Several studies have

shown that targeting the metabolism of cancer cells impacts the

growth of the cancer and inhibition of the glycolysis reduced the

biosynthesis of ATP, a constituent of DNA, RNA and phospholipids

(71), thus suppressing cancer cell

growth. PF inhibited ESCC cell proliferation by repressing

glycolysis through AMPK signalling (37). The activation of AMPK/forkhead box

(FOX)O3a/BCL-2-interacting mediator (BIM) signalling in an

oesophageal cell line induced apoptosis (37). In addition, Hu et al

(35) reported that the combination

of glycolytic inhibitor 2-DG or AMPK inhibitor CC with PF treatment

significantly inhibited the proliferation of gallbladder cancer.

Furthermore, PF dysregulated cholesterol homeostasis by enhancing

the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol in LL/2, 4T1, B16 and

CT26 cancer cells and decreased the total cholesterol in tumour

tissues of PF-treated mice (40).

Cholesterol plays a significant role in tumour cell growth

(72). Henceforth, PF has potential

anti-metabolic properties for the treatment of cancer.

Apoptosis and autophagy, programmed cell death

pathways crucial in maintaining cellular and organismal

homeostasis, are the main mechanisms researched in cancer (73,74).

PF was found to enhance apoptosis by inducing nuclear

fragmentation, poly-ADP ribose polymerase cleavage, caspase-3

activation and condensed nuclear chromatin (21,29,38).

Similarly, PF upregulated the expression levels of the proapoptotic

proteins BIM, BAX and p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA)

and downregulated the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 in pancreatic cancer

(31). Then again, PF induced G0/G1

phase arrest and, vehemently, cell apoptosis in lung cancer via the

mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (26). For instance, Xue et al

(26) reported that PF increased

the loss of ΔΨm. Thus, PF induces tumour suppression through

apoptosis. Despite that, Hung et al (25) remarked that PF's antiproliferative

effect on NSCLC cells is independent of apoptosis. In fact, instead

of the apoptotic characteristics, formation of autophagosome

protein light chain (LC)3B-II and expression of autophagosome

markers autophagy-related protein 5, Beclin-1 and p62 were recorded

in PF-treated NSCLC cells, implying that PF enhances cell death

through autophagy (25,73,75,76).

Indeed, PF promoted an increase in LC3-II and p62 protein

expression, phospholipid aggregates and lysosomal membrane damage

and consequently cell death in various cell lines (14,29,30).

In addition, in in vivo and in vitro studies of

PF-treated lung and pancreatic cancer, an increase in ER stress was

observed, which stimulated autophagy, noticeable by the

overexpression of binding protein, C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP)

and inositol-requiring 1α, increased unfolded protein response

(UPR) signals and activation of p38/MAPK (25,28).

Pre-treatment of the pancreatic cells with pharmacological

inhibitors such as sodium phenylbutyrate and mithramycin or

silencing of CHOP, followed by PF treatment, considerably

suppressed autophagy, revealing that PF-induced enhancement of ER

stress leads to autophagy in pancreatic cancer (28). Of note, blocking autophagy with

pharmacological inhibitors significantly increases PF-induced

apoptosis in AML cells (38).

However, treatment of BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 with autophagy inhibitors

and LC3B silencing followed by PF treatment resulted in a

significant reduction of apoptosis, suggesting that PF induces

autophagy-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic cancer (29). Similar results were obtained in RCC

cell lines, where PF induced autophagy-mediated apoptosis through

the upregulation of ER stress-mediated UPR (39). Therefore, PF enhances autophagy and

autophagy-mediated apoptosis in cancer.

In addition, PF constrained migration, adhesion,

invasion and metastasis in cancer cells (27,36).

Metastasis, a hallmark of cancer-cell migration from their initial

site, is a crucial factor of cancer therapy failure associated with

an unfavourable prognosis and cancer-associated death (77). PF treatment significantly reduced

cell migration and invasion by reducing the expression of

phosphorylated Rac family small GTPase 1 (Rac1), Rac1/2/3 and

Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 proteins in

triple-negative breast cancer cells (22). Furthermore, Kim et al

(33) revealed that PF inhibited

stemness by reducing the expression of SOX2, Nestin and optical

coherence tomography angiography and invasiveness by decreasing the

expression of integrin α6 and urokinase plasminogen activator

receptor in glioma-sphere forming cells. In addition, PF reduced

the potential for EMT, associated with cancer migration, invasion,

stemness and metastasis, of glioblastoma cancer models by

downregulating the expression of EMT markers (vimentin, Zeb 1,

N-cadherin, Snail and Slug) (33,78,79).

Besides that, PF reduced the expression of glioma-associated

oncogene homolog 1 and OCT4 in several glioblastoma cell lines

(32) and reduced lung cancer

migration in vivo and in vitro by blocking the

FAK-related migration signalling pathway and regulating the AKT and

MMP signalling pathway (26).

Despite PF's ability to constrain the mobility of bladder cancer

cells, no notable effects were registered in the urothelium and

epithelial tissue of UCB orthotopic xenograft mice (36). Therefore, PF exhibits anti-migration

and anti-metastasis properties without any side effects.

PF significantly inhibits angiogenesis, a mechanism

by which tumours acquire new nutrients for cell metabolism, leading

to cancer growth (80). Research by

Srivastava et al (23)

revealed that PF inhibits angiogenesis in in vitro and in

vivo models of triple-negative breast cancer by suppressing

VEGF-induced Src and Akt activation to prevent VEGF activity

(23). VEGF is a major angiogenic

agent in tumours that can initiate the growth and metastasis of

tumours (81). Furthermore, PF

increased the immune surveillance in glioblastoma cancer (33). Indeed, PF reduced the number of

regulatory T cells (Treg), suppressed the expression of FoxP3 and

CD4 by Tregs and increased M1 macrophages (increase of CD86 and

IL-12 expression), but also inhibited tumour inflammation markers

[C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4) and IFNγ] responsible for

tumour progression, as observed in PF-treated mouse glioblastoma

cancer model (33,34). CCL4 has been identified as a marker

of tumour proliferation in RCC and is associated with immune

checkpoint genes, including lymphocyte activating 3, cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 and programmed cell death protein

1 in RCC (82). Hence, the

reduction of CCL4 in glioblastoma by PF indicates that PF

suppresses the progression and immunity of the cancer cells.

Therefore, PF can impede angiogenesis in tumours and modulate the

immune system.

Lastly, PF considerably downregulated the expression

of the chemoresistance markers HER2, β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc

in PXT-resistant breast cancer (21). Indeed, chemoresistance promoted

cancer relapses and metastasis, thus leading to a more aggressive

form of cancer (83,84). Gupta et al (21) revealed that PF reduced the tumour

volume in PXT-resistant breast cancer female Balb/c mice by 40%,

but the combination of PF and PXT induced apoptosis and decreased

the expression of HER2, β-catenin and cyclin D1. Moreover, Du et

al (41) unveiled that PF has

radiosensitizing activity and can suppress the NHEJ activity/repair

of the ionizing radiation (IR)-induced DNA double-strand breaks

(DSBs). Radiosensitizers heighten the lethal effect of radiotherapy

on tumours by boosting DNA damage and free radical production

without affecting normal tissue (85) and PF impaired the IR-induced DNA

damage repair, enhanced the formation of DSB markers (γ-H2AX and

tumour protein 53 binding protein 1 foci) and inhibited the repair

of DSB post-IR in HeLa cells, thus promoting the cytotoxicity of IR

in HeLa cells (41). Taken

together, it can be suggested that PF is likely an excellent

chemo-radiotherapeutic agent.

Overall, PF exhibits several anticancer effects in

various cancer cell lines. PF affects the proliferation of cancer

cells, provides radiosensitizing activity, induces apoptosis and

autophagy, inhibits the invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of

cancer, and reduces the immunosuppressive effect of cancer

cells.

PF treatment induced apoptosis via the

mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in lung cancer and via the

suppression of Akt in glioblastoma. In addition, PF instigated

apoptosis through nuclear fragmentation, PARP cleavage and caspase

3 activation in leukaemia and through the activation of the BIM,

BAX and PUMA proapoptotic proteins in pancreatic cancer. PF

inhibited cell proliferation in lung cancer via mitochondrial ATP

energy loss and the inhibition of glycolysis, which consequently

led to autophagy and cell death. Similarly, in gallbladder, bladder

and oesophageal cancer, PF promoted apoptosis via inhibition of

glycolysis. However, in pancreatic cancer, PF induced autophagy via

induction of ER stress but suppressed the mTOR pathway in numerous

cancer cell lines. Upregulation of ROS by PF has been associated

with the ability of PF to enhance autophagy in renal cancer and

leukaemia. However, ROS led to the downregulation of cMyc and Sp

resulting in apoptosis in breast cancer. PF inhibited cell

migration via integrin and the VEGF pathway in breast cancer. PF

induced cell death via the activation of PP2A and PRLR signalling

in pancreatic cancer but PP2A in leukaemia cells. PF modulated the

immune system in glioblastoma cells by reducing the number of Tregs

and increasing M1 macrophages. In HeLa cells, PF was able to reduce

DNA repair by inhibiting the activity of NHEJ.

Limitation of PF and future direction

The dosage of PF as an anticancer drug exceeds the

clinical therapeutic range of PF as an antipsychotic. Indeed, the

10 mg/kg dose treatment of PF regularly used in in vivo

studies, including in chronic treatment, has successfully reduced

the tumour size and weight without triggering any major side

effects, as no significant changes in the body weight of the mice

and clinical chemical blood analysis parameters were observed

(29), and this 10 mg/kg dose of PF

is equivalent to the dose of 0.83 mg/kg in humans. Thus, for a

person weighing 60 kg, the human equivalent dose of PF would be ~50

mg (21). However, most of the

available studies indicate that mice are given PF treatment daily,

which exceeds the maximum weekly dose of PF for chronic

schizophrenia patients, which varies between 60 and 140 mg

(46,47). Of note, this high dose may cause

various adverse effects (49). In

fact, since PF interacts extensively with most G-protein coupled

receptors at levels consistent with the recommended anticancer

dosage, which is 50 mg per day for humans, the off-target central

nervous system (CNS) activity of PF as an anticancer drug will

exacerbate the drug's neurological side effects (86). Therefore, studying other mechanisms

of PF delivery to targeted sites, including the use of

nanotechnology, could potentially reduce the CNS side effects of

the drug.

Nonetheless, a study by Kim et al (33) on an orthotopic mouse glioblastoma

model revealed that a lower dose of 0.8 mg/week of PF, which is

equivalent to 4 mg/week in an adult patient with a body weight of

60 kg, showed effective antitumor activity. In this study, PF

significantly reduced the proliferation, invasion, migration and

stemness of glioblastoma cells, as well as the tumour size and

invasion in vivo, indicating that a lower dose of PF has a

potent anticancer effect (33).

Similarly, 0.12 mg/week of PF resulted in significant inhibition of

the tumour and prolonged the survival time in an LL/2 lung cancer

in vivo model (40).

Furthermore, Kim et al (33)

demonstrated that a combination of 0.8 mg/kg of PF with TMZ

provides better anticancer properties and prolonged survival in the

mouse model. Hence, a lower dose of PF alone or in combination with

other chemotherapeutic drugs may be considered for future clinical

and in vivo studies.

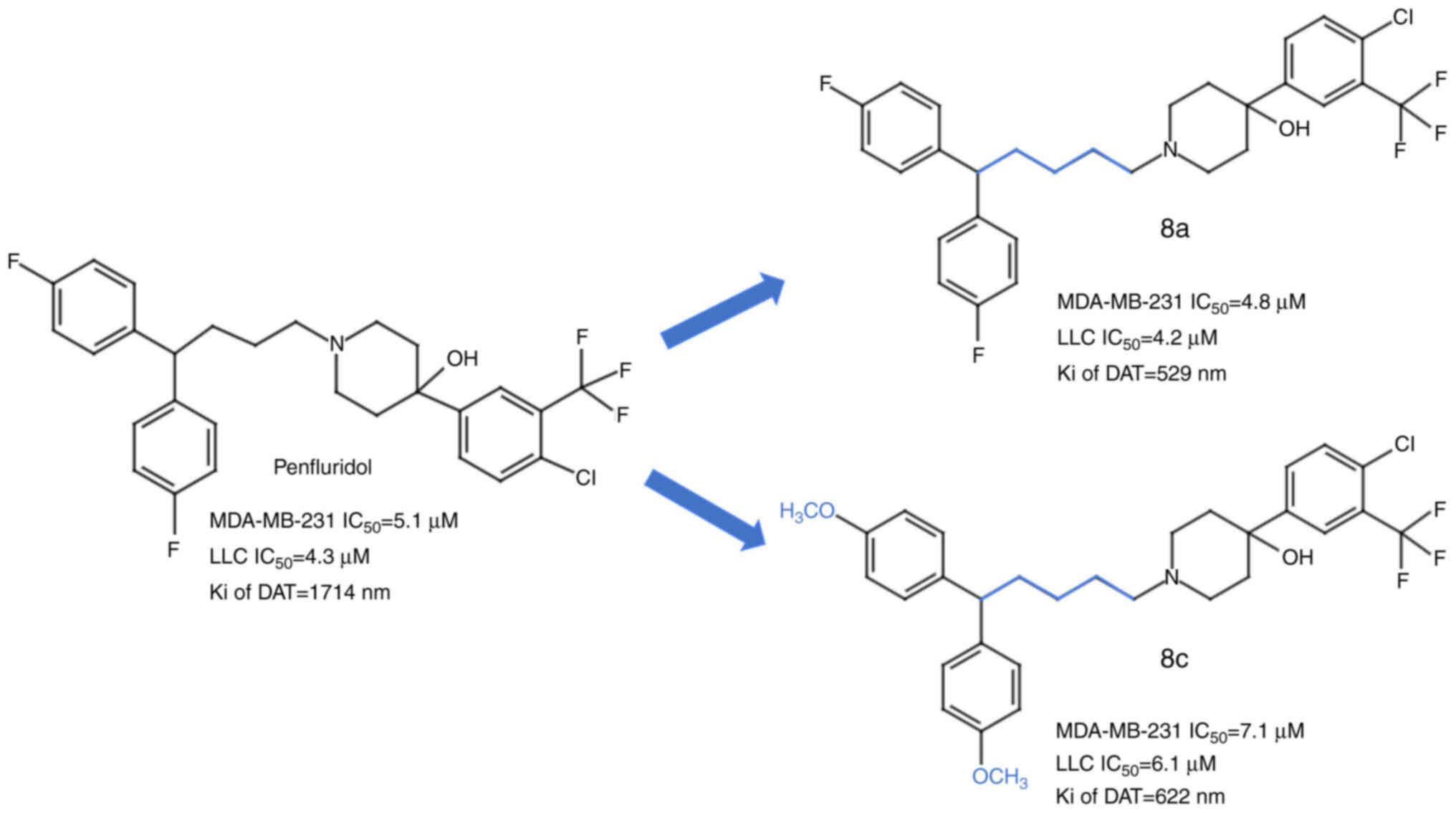

In addition, Ashraf-Uz-Zaman et al (86,87)

suggested the usage of PF derivatives with enhanced anticancer

activity and a weakened antipsychotic effect. Their study

identified 2 PF analogue compounds with less affinity for the CNS

and greater anticancer properties than PF (87) (Fig.

3). These compounds, which harbour modifications of PF in the

spacer linker by the addition of one carbon in the chain and the

introduction of a functional methoxy group (8c), displayed no

toxicity in mice and successfully inhibited the cell proliferation

of the metastatic triple-negative breast cancer cell line

MDA-MB-231 and the lung carcinoma cell line LLC (87). A further study by Ashraf-Uz-Zaman

et al (86) identified other

PF derivatives with the ability to induce apoptosis in the

MDA-MB-231 cell line without affecting the cell cycle. Nonetheless,

these compounds have yet to be tested and compared with PF in

various cancers. Therefore, more thorough research needs to be done

on the PF and PF derivatives to validate them as a clinical

therapeutic option for cancer.

Conclusion

This scoping review provides an overview of the

anticancer properties of PF in various cancers. It is crucial to

investigate potential cost- and time-effective drugs for managing

cancer. Based on the available studies, repurposing PF for cancer

treatment has promising effects, particularly in cancer with low

survival rates and high resistance to the current treatment. PF

inhibited the growth, metastasis and migration of various cancers,

including glioblastoma, as well as breast, lung, pancreatic, renal,

bladder and oesophageal cancer in vitro and in vivo

through distinctive mechanisms. Less than 10 µM of PF can provide

anticancer activity in vitro. Nonetheless, the in

vivo dose of PF exceeds the dose required for antipsychotic

treatment; therefore, the subsequent development of PF derivatives

with elevated anticancer and reduced antipsychotic activities was

deemed necessary. In addition, despite the approval of PF as a

valuable anticancer agent, dose-related side effects in the

clinical setting and in other types of cancer have yet to be

studied. Henceforth, extensive research on the effect of PF on

other cancers and in patients needs to be performed. In addition,

this scoping review focused on original articles published and

indexed in PubMed, Scopus and WoS before November 2023 in English.

Therefore, non-indexed, grey literature, studies in other languages

and review papers were overlooked. Furthermore, only articles

focusing on PF were considered and no clinical studies were

included in this review. Thus, future scoping reviews on the

anticancer properties of PF should include PF derivatives and

clinical studies when available.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of

Higher Education Malaysia (grant no.

FRGS/1/2023/SKK10/UITM/02/1).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AAIM contributed to the conceptualization,

methodology, validation, formal analysis, data collection,

visualisation, writing of the original draft and reviewing and

editing. AAR contributed to the conceptualization of the study,

reviewed and edited the manuscript as well as supervised the

preparation of and validated the manuscript. Data authentication is

not applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Asma Ali Ibrahim Mze (ORCID no.

0009-0002-1848-6160); Amirah Abdul Rahman (ORCID no.

0000-0002-3566-1787).

References

|

1

|

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I,

Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A and Bray F: Cancer statistics for the

year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. Apr 5–2021.(Epub ahead of

print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

World Health Organization (WHO), . Cancer.

WHO; Geneva: 2022

|

|

4

|

Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, Kuhn M, Yang J,

Jiao L, Wang Z, Li W, Geldsetzer P, Bärnighausen T, et al:

Estimates and projections of the global economic cost of 29 cancers

in 204 countries and territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol.

9:465–472. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gordon N, Stemmer SM, Greenberg D and

Goldstein DA: Trajectories of injectable cancer drug costs after

launch in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 36:319–325. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hendouei N, Saghafi F, Shadfar F and

Hosseinimehr SJ: Molecular mechanisms of anti-psychotic drugs for

improvement of cancer treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 856:1724022019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Qu LG, Brand NR, Chao A and Ilbawi AM:

Interventions addressing barriers to delayed cancer diagnosis in

low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Oncologist.

25:e1382–e1395. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Masuda T, Tsuruda Y, Matsumoto Y, Uchida

H, Nakayama KI and Mimori K: Drug repositioning in cancer: The

current situation in Japan. Cancer Sci. 111:1039–1046. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wouters OJ, McKee M and Luyten J:

Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New

Medicine to Market, 2009–2018. JAMA. 323:844–853. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Low ZY, Farouk IA and Lal SK: Drug

Repositioning: New approaches and future prospects for

life-debilitating diseases and the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak.

Viruses. 12:10582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Brown JS: Treatment of cancer with

antipsychotic medications: Pushing the boundaries of schizophrenia

and cancer. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 141:1048092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Vlachos N, Lampros M, Voulgaris S and

Alexiou GA: Repurposing antipsychotics for cancer treatment.

Biomedicines. 9:17852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shaw V, Srivastava S and Srivastava SK:

Repurposing antipsychotics of the diphenylbutylpiperidine class for

cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 68:75–83. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Varalda M, Antona A, Bettio V, Vachamaram

A, Yellenki V, Massarotti A, Baldanzi G and Capello D: Psychotropic

drugs show anticancer activity by disrupting mitochondrial and

lysosomal function. Front Oncol. 10:5621962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Soares BG and Lima MS: Penfluridol for

schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2006:CD0029232006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chokhawala K and Lee S: Antipsychotic

medications. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure

Island, FL: 2023

|

|

17

|

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK,

Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et

al: PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist

and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 169:467–473. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mak S and Thomas A: Steps for conducting a

scoping review. J Grad Med Educ. 14:565–567. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Arksey H and O'Malley L: Scoping studies:

Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol.

8:19–32. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hedrick E, Li XX and Safe S: Penfluridol

represses integrin expression in breast cancer through induction of

reactive oxygen species and downregulation of Sp transcription

factors. Mol Cancer Ther. 16:205–216. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gupta N, Gupta P and Srivastava S:

Penfluridol overcomes paclitaxel resistance in metastatic breast

cancer. Sci Rep. 9:50662019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ranjan A, Gupta P and Srivastava SK:

Penfluridol: An antipsychotic agent suppresses metastatic tumor

growth in triple-negative breast cancer by inhibiting integrin

signaling axis. Cancer Res. 76:877–890. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Srivastava S, Zahra FT, Gupta N, Tullar

PE, Srivastava SK and Mikelis CM: Low Dose of Penfluridol Inhibits

VEGF-Induced Angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 21:7552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lai TC, Lee YL, Lee WJ, Hung WY, Cheng GZ,

Chen JQ, Hsiao M, Chien MH and Chang JH: Synergistic tumor

inhibition via energy elimination by repurposing penfluridol and

2-Deoxy-D-Glucose in lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14:27502022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hung WY, Chang JH, Cheng Y, Cheng GZ,

Huang HC, Hsiao M, Chung CL, Lee WJ and Chien MH: Autophagosome

accumulation-mediated ATP energy deprivation induced by penfluridol

triggers nonapoptotic cell death of lung cancer via activating

unfolded protein response. Cell Death Dis. 10:5382019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Xue Q, Liu Z, Feng Z, Xu Y, Zuo W, Wang Q,

Gao T, Zeng J, Hu X, Jia F, et al: Penfluridol: An antipsychotic

agent suppresses lung cancer cell growth and metastasis by inducing

G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 121:1095982020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hung WY, Lee WJ, Cheng GZ, Tsai CH, Yang

YC, Lai TC, Chen JQ, Chung CL, Chang JH and Chien MH: Blocking

MMP-12-modulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition by repurposing

penfluridol restrains lung adenocarcinoma metastasis via

uPA/uPAR/TGF-β/Akt pathway. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 44:1087–1103. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ranjan A, German N, Mikelis C,

Srivenugopal K and Srivastava SK: Penfluridol induces endoplasmic

reticulum stress leading to autophagy in pancreatic cancer. Tumour

Biol. 39:10104283177055172017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ranjan A and Srivastava SK: Penfluridol

suppresses pancreatic tumor growth by autophagy-mediated apoptosis.

Sci Rep. 6:261652016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Dandawate P, Kaushik G, Ghosh C, Standing

D, Ali Sayed AA, Choudhury S, Subramaniam D, Manzardo A, Banerjee

T, Santra S, et al: Diphenylbutylpiperidine Antipsychotic Drugs

Inhibit Prolactin Receptor Signaling to Reduce Growth of Pancreatic

Ductal Adenocarcinoma in Mice. Gastroenterology. 158:1433–1449.e27.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chien W, Sun QY, Lee KL, Ding LW, Wuensche

P, Torres-Fernandez LA, Tan SZ, Tokatly I, Zaiden N, Poellinger L,

et al: Activation of protein phosphatase 2A tumor suppressor as

potential treatment of pancreatic cancer. Mol Oncol. 9:889–905.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ranjan A and Srivastava SK: Penfluridol

suppresses glioblastoma tumor growth by Akt-mediated inhibition of

GLI1. Oncotarget. 8:32960–32976. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kim H, Chong K, Ryu BK, Park KJ, Yu MO,

Lee J, Chung S, Choi S, Park MJ, Chung YG and Kang SH: Repurposing

penfluridol in combination with temozolomide for the treatment of

glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 11:13102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ranjan A, Wright S and Srivastava SK:

Immune consequences of penfluridol treatment associated with

inhibition of glioblastoma tumor growth. Oncotarget. 8:47632–47641.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hu J, Cao J, Jin R, Zhang B, Topatana W,

Juengpanich S, Li S, Chen T, Lu Z, Cai X and Chen M: Inhibition of

AMPK/PFKFB3 mediated glycolysis synergizes with penfluridol to

suppress gallbladder cancer growth. Cell Commun Signal. 20:1052022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

van der Horst G, van de Merbel AF, Ruigrok

E, van der Mark MH, Ploeg E, Appelman L, Tvingsholm S, Jäätelä M,

van Uhm J, Kruithof-de Julio M, et al: Cationic amphiphilic drugs

as potential anticancer therapy for bladder cancer. Mol Oncol.

14:3121–3134. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zheng C, Yu X, Liang Y, Zhu Y, He Y, Liao

L, Wang D, Yang Y, Yin X, Li A, et al: Targeting PFKL with

penfluridol inhibits glycolysis and suppresses esophageal cancer

tumorigenesis in an AMPK/FOXO3a/BIM-dependent manner. Acta Pharm

Sin B. 12:1271–1287. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wu SY, Wen YC, Ku CC, Yang YC, Chow JM,

Yang SF, Lee WJ and Chien MH: Penfluridol triggers cytoprotective

autophagy and cellular apoptosis through ROS induction and

activation of the PP2A-modulated MAPK pathway in acute myeloid

leukemia with different FLT3 statuses. J Biomed Sci. 26:632019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tung MC, Lin YW, Lee WJ, Wen YC, Liu YC,

Chen JQ, Hsiao M, Yang YC and Chien MH: Targeting DRD2 by the

antipsychotic drug, penfluridol, retards growth of renal cell

carcinoma via inducing stemness inhibition and autophagy-mediated

apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 13:4002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wu LL, Liu YY, Li ZX, Zhao Q, Wang X, Yu

Y, Wang YY, Wang YQ and Luo F: Anti-tumor effects of penfluridol

through dysregulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 15:489–494. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Du J, Shang J, Chen F, Zhang Y, Yin N, Xie

T, Zhang H, Yu J and Liu F: A CRISPR/Cas9-Based screening for

non-homologous end joining inhibitors reveals ouabain and

penfluridol as radiosensitizers. Mol Cancer Ther. 17:419–431. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, Schellekens KH,

Lenaerts FM, Verbruggen FJ, Van Nueten JM and Schaper WK: The

pharmacology of penfluridol (R 16341) a new potent and orally

long-acting neuroleptic drug. Eur J Pharmacol. 11:139–154. 1970.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Airoldi L, Marcucci F, Mussini E and

Garattini S: Distribution of penfluridol in rats and mice. Eur J

Pharmacol. 25:291–295. 1974. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Andrade C: Psychotropic drugs with long

half-lives: Implications for drug discontinuation, occasional

missed doses, dosing interval, and pregnancy planning. J Clin

Psychiatry. 83:22f145932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bhattacharyya R, Bhadra R, Roy U,

Bhattacharyya S, Pal J and Saha SS: Resurgence of penfluridol:

Merits and demerits. East J Psychiatry. 18:23–29. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Nikvarz N, Vahedian M and Khalili N:

Chlorpromazine versus penfluridol for schizophrenia. Cochrane

database Syst Rev. 9:CD0118312017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang RI, Larson C and Treul SJ: Study of

penfluridol and chlorpromazine in the treatment of chronic

schizophrenia. J Clin Pharmacol. 22:236–242. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Andrade C: The practical importance of

half-life in psychopharmacology. J Clin Psychiatry.

83:22f145842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Clarke Z: Penfluridol. Elsevier; New York,

NY: pp. 1–4. 2007

|

|

50

|

Enyeart JJ, Biagi BA, Day RN, Sheu SS and

Maurer RA: Blockade of low and high threshold Ca2+ channels by

diphenylbutylpiperidine antipsychotics linked to inhibition of

prolactin gene expression. J Biol Chem. 265:16373–16379. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Cabrera M, Gomez N, Remes Lenicov F,

Echeverría E, Shayo C, Moglioni A, Fernández N and Davio C: G2/M

cell cycle arrest and tumor selective apoptosis of acute leukemia

cells by a promising benzophenone thiosemicarbazone compound. PLoS

One. 10:e01368782015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Abbas T and Dutta A: p21 in cancer:

Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:400–414. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Boudreau RT, Conrad DM and Hoskin DW:

Apoptosis induced by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibition in T

leukemia cells is negatively regulated by PP2A-associated p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase. Cell Signal. 19:139–151. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Nakamura H and Takada K: Reactive oxygen

species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer

Sci. 112:3945–3952. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yang H, Villani RM, Wang H, Simpson MJ,

Roberts MS, Tang M and Liang X: The role of cellular reactive

oxygen species in cancer chemotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

37:2662018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Shah MA and Rogoff HA: Implications of

reactive oxygen species on cancer formation and its treatment.

Semin Oncol. 48:238–245. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Singh R and Manna PP: Reactive oxygen

species in cancer progression and its role in therapeutics. Explor

Med. 3:43–57. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Perillo B, Di Donato M, Pezone A, Di Zazzo

E, Giovannelli P, Galasso G, Castoria G and Migliaccio A: ROS in

cancer therapy: The bright side of the moon. Exp Mol Med.

52:192–203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kim SJ, Kim HS and Seo YR: Understanding

of ROS-Inducing strategy in anticancer therapy. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2019:53816922019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Miller DM, Thomas SD, Islam A, Muench D

and Sedoris K: c-Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res.