Introduction

The COVID-19 epidemic began in China at the end of

2019, and became a pandemic by 2020(1). The first case of infection in Japan

was reported on January 14, 2020(2). As the number of infected individuals

increased rapidly, the government and municipalities called for

voluntary restraints on events that could increase the risk of

infection, such as cross-prefecture travel and dining, affecting

numerous areas, including public administration, medical facilities

and educational institutions. Medical facilities took measures such

as postponing routine medical examinations and non-urgent

surgeries. To reduce the risk of infection, patients began to avoid

visits to doctors, particularly for pediatrics and otolaryngology

in Japan (3). In emergency

transport, an increase in the number of difficult cases and a

longer time spent at the scene were noted (4). Similarly, Taiwan and Germany

experienced a decline in the number of emergency transport requests

(5,6), making it challenging to find suitable

facilities for certain cases (7).

The present study examined the impact of COVID-19

infection on the emergency transfers of patients with obstetric and

gynecological diseases in Kochi Prefecture, Japan. Kochi Prefecture

has a population of ~680,000. In 2021, the percentage of older

adults aged ≥65 years was 35.2%, markedly higher than the national

average of 28.4% (8). Surrounded

by the Pacific Ocean and the Shikoku Mountains, Kochi Prefecture is

situated in a difficult location for receiving medical care beyond

the prefectural border, apart from some areas, and the provision of

medical care must be completed within the prefecture. The numbers

of physicians and hospital beds per 100,000 individuals have

exhibited a steady decline in Kochi Prefecture. However, it is

still higher than the national average, partly owing to the decline

in the population in Kochi. As of 2022, there were 313.9 physicians

(national average, 253.6) and 1,105.2 general hospital beds

(national average, ~701.4) per 100,000 individuals (9). According to the Fire and Disaster

Management Agency of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and

Communications, there were about 40,000 emergency medical calls per

year, with 581.5 calls per 10,000 individuals in 2021. In the same

year, the national figure was 491.2 dispatches per 10,000, and

Kochi Prefecture had a higher number of dispatches per population

than the national average (10).

As of 2021, seven general hospitals, six clinics and

one midwifery center were handling childbirth deliveries in Kochi

Prefecture. Of note, ~30% of deliveries in Kochi are performed at

clinics. Owing to the aging of obstetricians and gynecologists,

more temporary facilities have suspended deliveries in recent

years. Thus, obstetric and gynecological care, particularly

perinatal care, is not robust. Although the number of deliveries is

decreasing with the declining birthrate, the number of high-risk

pregnancies is increasing owing to the higher age of pregnant

women, patients with complex social backgrounds and pregnancies

complicated by psychiatric disorders. Moreover, the number of cases

that require individualized care is increasing.

Notably, access to and the quality of medical care

in Japan is high by global standards, and the disparity between

regions in the country is the lowest worldwide (11). However, the regional cities in

Japan are experiencing a declining population and an uneven

distribution of medical facilities and physicians. The challenges

in rural areas, where medical resources and medical institutions

are limited, could differ from those in urban areas, where there

are many medical institutions or major medical departments, such as

internal medicine.

When a situation such as the recent pandemic occurs

and causes a prolonged disruption to the medical field, making the

most of limited medical resources is an important issue. The

present study first examined the extent to which the pandemic

caused confusion in the medical field, focusing on the field of

obstetrics and gynecology, which is not directly related to the

practice of COVID-19 medical care. As regards making the most of

limited medical resources, by focusing on departments with limited

resources, the present study provides insight that may be useful

during emergencies. The changes in emergency transfers for

obstetric and gynecological cases in Kochi Prefecture in the pre-

and post-pandemic period were compared in an aim to discover clues

with which to solve the issue of facilitating emergency medical

care in an emergency situation.

Subjects and methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted by

extracting data on emergency transport of obstetric and

gynecological diseases in Kochi Prefecture from January, 209 to

December, 2021 from the database ‘Kochi-Iryo-Net’ (https://www.kochi-iryo-net/).

Japan has a nationwide fire/ambulance service that

can be availed by dialing the emergency number 119. This

taxpayer-funded service is available to anyone, anytime and

anywhere at no charge. When an individual calls 119 during an

emergency, the nearest fire station dispatches an ambulance to the

patient, locates a receiving hospital based on the chief complaint

and condition of the patient, and subsequently transfers the

patient to medical personnel. Fire stations are operated and

managed by municipal governments, and each station is equipped with

fire engines and ambulances according to the size of the local

population. As of 2021, there were 41 fire stations in Kochi

Prefecture.

The Kochi-Iryo-Net is a database established in 2015

as part of the medical and disaster information system of Kochi

Prefecture. The database contains information about fire and

ambulance dispatches and crew details, dates and times of calls,

destination medical institutions and distance between patients from

the fire department. Upon arrival at the destination (medical

institution), an attending doctor recorded pertinent information

regarding institution names, locations where patients were

collected, types and degrees of conditions or urgency in the

institutional medical record database. The Kochi Prefectural

Government then integrated this information into the Kochi-Iryo-Net

database. The data that support the findings of the present study

are available from the Kochi Prefecture database. However, these

data are not publicly available as they report the surveillance

conducted by Kochi Prefecture Healthcare Policy Division Department

for monitoring emergency medical care.

Study participants

From the Kochi-Iryo-Net, data were extracted on

transports made between January, 2019 and December, 2021 that

indicated obstetrics and gynecology as the disease classification.

Since the disease name was written in a free description format by

the receiving physician, it was additionally converted to the

ICD-10 code for the corresponding disease name.

The period from January to December, 2019 was

defined as the pre-expansion period of COVID-19 infection

(pre-pandemic), and that from January, 2020 to December, 2021 was

considered as the expansion period of COVID-19 infection (during

the post-pandemic period).

In order to protect patient privacy, all data were

anonymized by the Kochi Prefecture Medical Policy Division. The

data obtained were already in an anonymized state. The study

protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kochi University

School of Medicine (approval no. 2021-142). The present study was

conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and

Biological Research Involving Human Subjects by the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; the Ministry of

Health, Labour and Welfare; and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and

Industry and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 amendment).

Variables

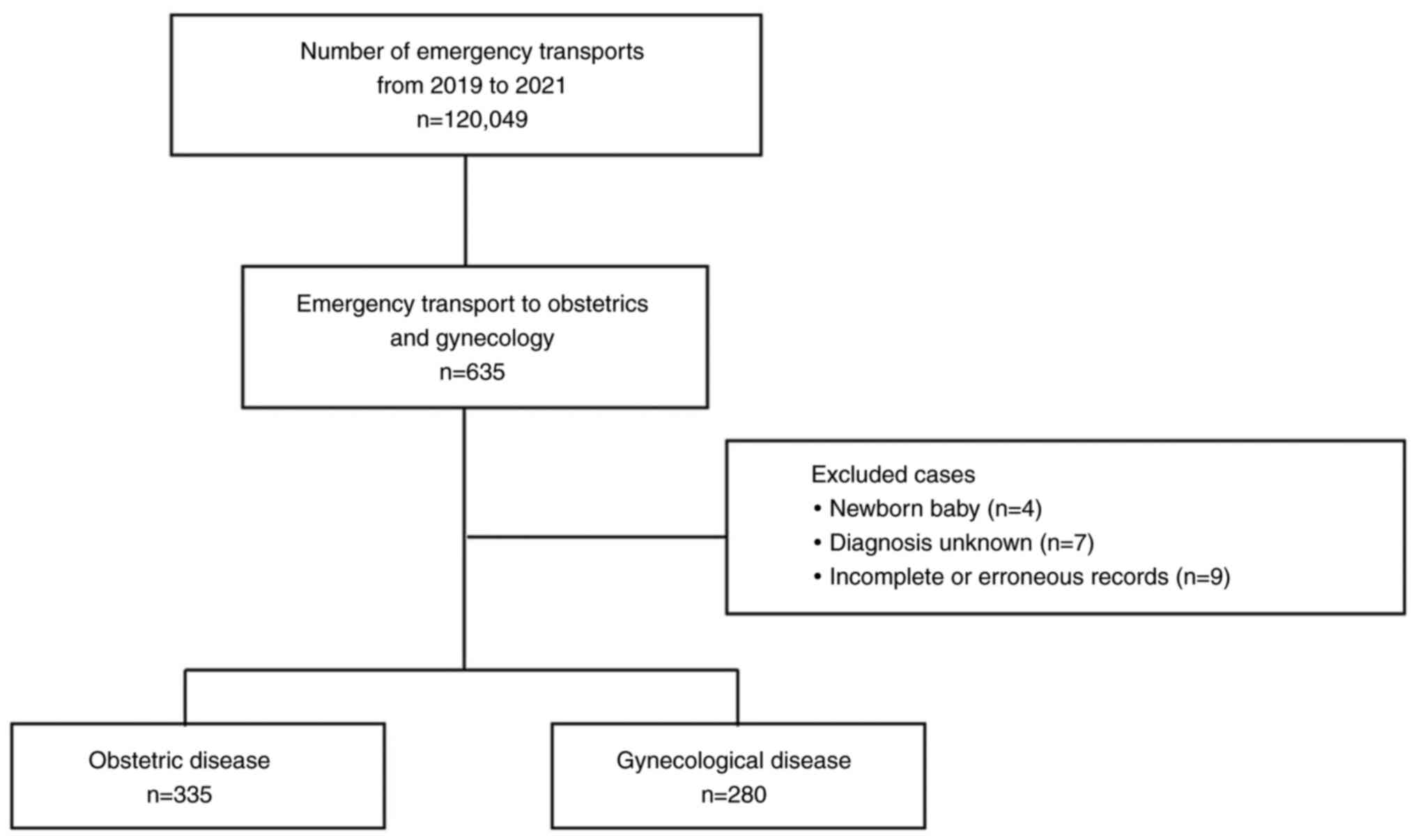

Only the cases classified as obstetrics and

gynecology diseases were included in the present study. Cases

classified as ‘O: Pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum’ by the

ICD-10 code were classified as obstetric cases, and those with

other codes were classified as gynecological cases. Newborns who

were transported together with their mothers for out-of-hospital

deliveries (n=4), cases with unknown diseases (n=7), and those with

incorrectly entered or incompletely recorded transport dates and

times (n=9) were excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

The type of transport was examined separately for

transfers and non-transfers. The time required for transport was

examined in terms of the time required to arrive at the scene, time

spent at the scene, and time from the emergency call to the

transfer to the physician at the receiving facility.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata/MP 16.0

software (StataCorp LLC). Chi-squared tests were performed to

evaluate the number of transports, severity and type of transport,

and the P-values obtained were corrected using the Bonferroni

method. A Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to examine age and

transport time. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Between January, 2019 and December, 2021, a total of

120,049 emergency cases were transported in Kochi Prefecture, of

which 635 were sent to obstetrics and gynecology departments

(Fig. 1).

The number of transports, post-transportation

outcomes and type of transport for obstetric diseases are presented

in Table I. However, there was no

significant difference in the number of transports before and after

COVID-19. There were 88 transfers between hospitals (75.2%) before

the spread of COVID-19 infection; however, the number decreased to

77 (72.6%) in 2020 and 68 (60.7%) in 2021. As regards

post-transportation outcomes, 2.6% of cases were managed as

outpatients before the spread of COVID-19 infection; however, after

the spread of COVID-19 infection, the number of cases increased to

6 (5.7%) and 21 (18.8%) in 2020 and 2021, respectively. The number

of cases admitted to the hospital after transport was 114 (97.4%)

in 2019, 100 (94.3%) in 2020 and 91 (81.2%) in 2021, exhibiting a

decreasing trend. During this period, no cases were deceased at the

time of transport.

| Table IEmergency transport of patients with

obstetric diseases. |

Table I

Emergency transport of patients with

obstetric diseases.

| | Pre-pandemic | Post-pandemic | |

|---|

| Parameter | All | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | P-value |

|---|

| Number of

transports | | | | | 0.98 |

|

All | 120,049 | 41,740 | 38,585 | 39,724 | |

|

Obstetric

disease | 335 | 117 | 106 | 112 | |

| Outcome, n (%) | | | | | <0.01 |

|

Outpatient | 30 | 3 (2.6) | 6 (5.7) | 21 (18.8) | |

|

Hospitalization | 305 | 114 (97.4) | 100 (94.3) | 91 (81.2) | |

| Type of transport, n

(%) | | | | | 0.04 |

|

Transfer | 233 | 88 (75.2) | 77 (72.6) | 68 (60.7) | |

|

No

transfer | 102 | 29 (24.8) | 29 (27.4) | 44 (39.3) | |

The numbers of childbirth deliveries and childbirth

delivery facilities in Kochi Prefecture over the 3-year period are

presented in Table II. The number

of emergency transports for obstetric diseases as a percentage of

the number of childbirth deliveries remained at a similar rate of

2.5-2.7% per year. The outcome, age of the patients, and time

required for transport for the cases excluding transfers are

presented in Table III.

Significantly fewer cases were admitted to the hospital after

transport, and more patients were managed as outpatients. The age

of tge patients transported did not differ significantly. The time

required to arrive at the scene was 7-8 min, the time spent at the

scene was 9-12 min, and the time elapsed from the emergency call to

the physician at the receiving facility was 35-40 min; however,

there was no significant difference in time to transport before and

after the spread of COVID-19 infection.

| Table IINumber of deliveries, delivery

facilities and transports in Kochi Prefecture. |

Table II

Number of deliveries, delivery

facilities and transports in Kochi Prefecture.

| Parameter | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|

| No. of childbirth

deliveries in the prefecture | 4,731 | 4,303 | 4,090 |

| Facilities advocating

obstetrics and gynecology | 13 | 14 | 14 |

| Childbirth delivery

facility | | | |

|

General

hospital | 7 | 7 | 7 |

|

Clinic | 7 | 6 | 6 |

|

Maternity

hospital | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Transport | 117 | 106 | 112 |

|

(per

childbirth delivery) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| Transfer | 88 | 77 | 68 |

|

(per

childbirth delivery) | 1.86 | 1.79 | 1.66 |

| No transfer | 29 | 29 | 44 |

|

(per

childbirth delivery) | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Table IIIEmergency transport patients other

than those transferred owing to obstetric diseases. |

Table III

Emergency transport patients other

than those transferred owing to obstetric diseases.

| | Pre-pandemic | Post-pandemic | |

|---|

| Parameter | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | P-value |

|---|

| No. of

transports | 29 | 29 | 44 | |

| Outcome, n (%) | | | | 0.03 |

|

Outpatient | 3 (10.3) | 6 (20.7) | 19 (43.2) | |

|

Hospitalization | 26 (89.7) | 23 (79.3) | 25 (56.8) | |

| Age, years; median

(quartile range) | 30 (25-30) | 30 (25-35) | 30 (25-35) | 0.07 |

| Time of transport,

min; median (quartile range) | | | | |

|

Time

required to arrive on-site | 7 (6-9) | 8 (7-10) | 8 (6-10) | 0.34 |

|

On-site

time | 9 (6-13) | 10 (7-13) | 12 (7.5-16) | 0.13 |

|

Time

required for hospitalization | 34 (27-44) | 42 (28-49) | 37 (31.5-45) | 0.41 |

The number of transports, post-transportation

outcomes and type of transport for gynecological diseases are

presented in Table IV. The

outcome, age of the patient and time required for transport for the

cases excluding transfers are presented in Table V. No significant differences were

observed in outcomes, type of transport, the age of the patients

and time required for transport.

| Table IVEmergency transport of patients with

gynecological diseases. |

Table IV

Emergency transport of patients with

gynecological diseases.

| | Pre-pandemic | Post-pandemic | |

|---|

| Parameter | All | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | P-value |

|---|

| Number of

transports | | | | | 0.35 |

|

All | 120,049 | 41,740 | 38,585 | 39,724 | |

|

Gynecological

disease | 280 | 108 | 81 | 91 | |

| Outcome, n (%) | | | | | 0.18 |

|

Outpatient | 144 | 58 (53.7) | 42 (51.9) | 44 (48.4) | |

|

Hospitalization | 136 | 50 (46.3) | 39 (48.1) | 47 (51.6) | |

| Type of transport,

n (%) | | | | | 0.97 |

|

Transfer | 56 | 21 (19.4) | 16 (19.8) | 19 (20.9) | |

|

No

transfer | 224 | 87 (80.6) | 65 (80.3) | 72 (79.1) | |

| Table VPatients transported to emergency

departments other than transfers owing to gynecological

diseases. |

Table V

Patients transported to emergency

departments other than transfers owing to gynecological

diseases.

| | Pre-pandemic | Post-pandemic | |

|---|

| Parameter | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | P-value |

|---|

| No. of

transports | 87 | 65 | 72 | |

| Outcome, n (%) | | | | 0.71 |

|

Outpatient | 54 (62.1) | 42 (64.6) | 43 (59.7) | |

|

Hospitalization | 33 (37.9) | 23 (35.4) | 29 (40.3) | |

| Age, years; median

(quartile range) | 35 (20-50) | 35 (25-50) | 37.5 (25-62.5) | 0.40 |

| Time of transport,

min; median (quartile range) | | | | |

|

Time

required to arrive on site | 8 (7-10) | 8 (6-10) | 8 (6-9.5) | 0.51 |

|

On-site

time | 13 (9-18) | 14 (10-18) | 14 (9-18) | 0.95 |

|

Time

required for hospitalization | 36 (30-42) | 36 (30-42) | 39 (30.5-49.5) | 0.54 |

Discussion

Using data on emergency transports in Kochi

Prefecture, the present study examined the impact of COVID-19

infection on emergency obstetric and gynecological care. No marked

changes were observed in the number of emergency transports, or the

time required for transport, suggesting that the measures taken to

prevent infection had minimal impact on emergency care.

To date, at least to the best of our knowledge, no

study has examined emergency transport for obstetrics and

gynecology cases on a regional basis. In Osaka, one of the largest

cities in Japan, the number of cases of difficulty in transporting

pregnant women was lower than that of other cases and remained the

same even under pandemic conditions (12).

The present study covered the period from 2019 to

2021; 2019 was considered pre-pandemic, and 2020 and 2021 were

during the post-pandemic period. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic,

in 2020, unknown infectious diseases spread globally, infection

control measures were in a state of flux, and medical practices

underwent a period of great uncertainty (13). In addition, numerous infected

individuals were older adults with a high risk of serious illness

if they became infected (13). By

2021, infection control measures had been established to a certain

extent. The number of infected individuals was increasing, although

the main source of infection was young individuals, and the number

of severe cases decreased. During this period, the number of

pregnant women infected with COVID-19 also increased, and infected

pregnant women were at a high risk of developing severe illness

(14). Thus, the situations of

infected patients varied slightly during the pandemic.

As regards the impact of COVID-19 on obstetrics and

gynecology during this period, in April 2020, the Japanese Society

of Reproductive Medicine issued a statement on the postponement of

fertility treatment (15), and the

Japanese Society of Surgery proposed the postponement of

non-emergency surgery (16). In

fact, according to a survey by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, the number of surgeries (for both benign and malignant

diseases) and the number of patients seeking fertility treatment

decreased (17). As regards

prenatal check-ups, some facilities reported that they made efforts

to provide remote medical care as an infection control measure

(18,19); however, they were not requested to

take measures such as reducing the number of patient visits.

However, there were calls for individuals to refrain

from moving to other prefectures as a countermeasure against

infection. As a result, some facilities refused to transfer

patients from other prefectures for delivery, or requested that

individuals stay at home for 2 weeks after moving.

In the present study, emergency transport in the

field of obstetrics and gynecology was examined separately for

obstetric and gynecological diseases during the period when the

above measures were taken in daily medical care. For gynecological

diseases, the number of transports and the time required for

transport did not change over the 3-year study period, and it is

considered that the same operations carried out in peacetime were

continued even in the pandemic situation.

By contrast, in Kochi Prefecture, there were two

changes in obstetric conditions: A decrease in the proportion of

transfers and a decrease in the number of patients admitted to

hospital after emergency transport (Table I). Transfer to another hospital for

obstetric disorders refers to the transfer of a pregnant woman who

had been managed in a primary or secondary facility to a

higher-level facility with a neonatal intensive care unit or

maternal fetal intensive care unit owing to a sudden change in her

condition. The decline in hospital transfers may be due to changes

in the management of pregnant women, such as the early referral of

patients who are at a high risk for preterm birth, etc., to

higher-level facilities. In cases in which shortening of the

cervical length or uterine contractions were observed during the

preterm period at the primary facility, hospitalization management

was previously administered at the primary facility and pregnant

women were transported when the disease worsened. During this

period, however, there was an increase in referrals to higher-level

facilities at an early stage, rather than hospitalization

management at primary facilities. This may have been due in part to

a decrease in the number of primary facilities where

hospitalization management could be provided. To avoid bringing

infections into the hospital, patient hospitalizations other than

those for delivery may have been avoided as much as possible.

Subsequently, the decrease in the number of cases

requiring hospitalization after transportation was considered.

Usually, pregnant women have a family doctor and receive regular

check-ups. If there is a change in their condition, they first

consult with their family doctor and ask whether they should

schedule an appointment. The fact that pregnant women request an

ambulance means that their condition has suddenly changed and they

are not in a situation in which they can consult by phone. However,

there was an increase in the number of cases not requiring

hospitalization as they were judged to have been mild. This finding

may be due to an increase in the number of cases that were

undecided between hospitalization and careful outpatient management

at the time of transport, and outpatient management was opted over

hospitalization. This situation may have occurred as numerous

facilities imposed visiting restrictions due to COVID-19, and

patients preferred outpatient management, or as medical

institutions avoided hospitalization due to a hospital bed shortage

or to reduce the chance of bringing COVID-19 into the hospital.

However, it cannot be ruled out that there was an increase in the

number of cases in which emergency calls were made even though the

symptoms were mild. This could be due to the social unrest caused

by COVID-19 or also since more facilities blocked deliveries and

emergency calls made on holidays and during the night as the family

doctor could not be reached. This point requires further

investigation as countermeasures vary depending on the cause. In

the former case, it is necessary to raise awareness about the

proper use of ambulances. In the latter case, it is necessary to

review the medical system. In addition, the indications and timing

of therapeutic interventions, such as inpatient treatment, may

differ depending on whether the patient is being treated at a

primary or higher-level facility. Moreover, during this period, the

pandemic may have affected the implementation of these

interventions. Using a more objective measure of severity to

confirm what changed (e.g., scoring urgency based on patient

background, symptoms, laboratory findings) was also considered

crucial. In addition, accumulating more detailed information on

symptoms and findings may facilitate the future development of

tools to assist diagnosis using artificial intelligence and other

methods (20,21).

The present study used a database covering emergency

transports within Kochi Prefecture. The number of individuals

infected with COVID-19 is reported by prefecture (those diagnosed

with COVID-19 are tabulated by prefecture and published on

prefectural websites, etc.), which makes it easier to identify

trends based on infection status than reports from a single center,

which we believe is a strength of this study.

Despite its strengths, the present study has the

following limitations: The names of diseases in the database were

freely described, and for some cases, it was difficult to grasp the

number of weeks of pregnancy and accurate diagnoses. There were

also cases in which the outcome was unknown. In the field of

obstetrics, maternal deaths, stillbirths, premature births and

other complications have increased since the pandemic occurred

(22,23). Conversely, there have been reports

of an increase in maternal transport, although the rate of

premature births remained the same as before the pandemic (24). Details such as changes in diseases

could not be evaluated in the present study. In addition, the

present study evaluated the cases of difficult transportation only

based on the time required for transportation. Difficult

transportation is generally evaluated by the number of facilities

that were requested to accept transportation and the extension of

on-site stay time. However, owing to the unique circumstances of

Kochi, these indicators may not be able to determine difficult

transportation. First, the number of facilities contacted was not

listed in the data used herein. In Kochi, the number of hospitals

is limited, and the number of facilities that can accept

transportation is limited. Therefore, the number of times

transportation was requested was not an indicator of cases of

difficult transportation even if it was listed. Second, on-site

stay time was associated with the time it takes to determine the

patient's destination, which is usually performed after the patient

has been placed in an ambulance. However, Kochi Prefecture is

geographically wide from east to west, and medical institutions are

concentrated in the center of the prefecture. Therefore, in some

areas, the time on site may not be an indicator of difficulty of

transport, as patients often leave the site and head to the central

part of the prefecture before a decision is made on where to

transport them. The fact that hospitals could maintain normal

medical functions to a certain extent in the department of

obstetrics and gynecology, which was not directly affected by

COVID-19 infection, was a factor that prevented major disruptions

in emergency transport. With fewer facilities handling deliveries

owing to a shrinking population, it is unclear whether facilities

can maintain their medical functions when a new pandemic or other

socially disruptive event occurs in the future. Furthermore, it has

been predicted that Kochi Prefecture will be hit by a huge Nankai

Trough earthquake in the near future, at which time medical

treatment functions will be temporarily paralyzed, and will likely

take some time to recover (25).

In considering emergency obstetrics and gynecology care in rural

areas, one future challenge is establishing a medical care system

that does not disadvantage patients, such as by decreasing the

number of delivery facilities, in an environment that changes year

by year. To this end, strengthening cooperation between hospitals

and clinics, applying artificial intelligence technology to support

diagnoses, using information and communication technology, and

broadening the area of medical cooperation are some of the measures

that can be implemented.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Ryuhei Nagai,

Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Kochi Medical School, Kochi University, Dr Nagamasa Maeda,

Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kochi

Medical School, Kochi University, Dr Kingo Nishiyama, Professor of

the Department of Disaster and Emergency Medicine, Kochi Medical

School, Kochi University, and Dr Narifumi Suganuma, Professor of

the Department of Environmental Medicine, Kochi Medical School,

Kochi University, for their advice and guidance in the preparation

of this study. The authors are also grateful to Ms. Marina Minami,

Department of Environmental Medicine, Integrated Center for

Advanced Medical Technologies (ICAM-Tech), Kochi Medical School,

Kochi University, for her great support and specific advice on

statistical analysis and for proofreading the entire manuscript.

The authors also received suggestions from Ms. Hina Miyata, Medical

Course, Kochi Medical School, Kochi University, who is conducting

similar research. Above all, the authors would like to thank the

staff of the Kochi Prefecture Medical Policy Division for providing

data for this study, as well as the members of the emergency

medical team and other medical professionals who cooperated with

Kochi-Iryo-Net daily to collect information.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the present findings are under

license from Kochi Prefecture and are not publicly available. The

dataset is surveillance conducted by the Kochi Prefecture

Healthcare Policy Division Department, for monitoring emergency

medical care and is not publicly available, although its use may be

permitted following ethical review.

Authors' contributions

TT was involved in the conceptualization and

methodology of the study, and in the writing the original draft of

the manuscript. MM and HM were involved in the study methodology.

RN and KN were involved in the study methodology, and supervised

the study. TT and MM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors (TT, MM, HM, RN, KN, NS, and NM) were involved in the

interpretation of and in reporting the findings of the study. All

authors were involved in the conceptualization of the study,

contributed to, and have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

An opt-out recruitment was adopted to obtain consent

in the present study on the Kochi-Iryo-Net website. There was no

objection from participants to use their information. The present

study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Kochi

University School of Medicine in 2021 (no. 2021-142). The present

study was approved by and complied with the Ethical Guidelines for

Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects of the

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; the

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; and the Ministry of

Economy, Trade and Industry and the Declaration of Helsinki (2013

amendment).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chams N, Chams S, Badran R, Shams A, Araji

A, Raad M, Mukhopadhyay S, Stroberg E, Duval EJ, Barton LM and

Hussein IJ: COVID-19: A multidisciplinary review. Front Public

Health. 8(383)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Imai N, Gaythorpe KAM, Bhatia S, Mangal

TD, Cuomo-Dannenburg G, Unwin HJT, Jauneikaite E and Ferguson NM:

COVID-19 in Japan, January-March 2020: Insights from the first

three months of the epidemic. BMC Infect Dis.

22(493)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yumiko M: Impact of new coronavirus

infections on clinic management. Japan Medical Association Research

Institute, 2021 (In Japanese). https://www.jmari.med.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/RE106.pdf.

Accessed April 30, 2024.

|

|

4

|

Igarashi Y, Yabuki M, Norii T, Yokobori S

and Yokota H: Quantitative analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on

the emergency medical services system in Tokyo. Acute Med Surg.

8(e709)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tai HCH, Kao YH, Lai YW, Chen JH, Chen WL

and Chung JY: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical-seeking

behavior in older adults by comparing the presenting complaints of

the emergency department visits. BMC Emerg Med.

23(63)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hegenberg K, Althammer A, Gehring C,

Prueckner S and Trentzsch H: Pre-hospital emergency medical

services utilization amid COVID-19 in 2020: Descriptive study based

on routinely collected dispatch data in Bavaria, Germany.

Healthcare (Basel). 11(1983)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ryu MY, Park HA, Han S, Park HJ and Lee

CA: Emergency transport refusal during the early stages of the

COVID-19 pandemic in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. Int J Environ

Res Public Health. 19(8444)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kochi Prefecture: Chapter 2: Current

Situation and Future Projections for the Elderly, etc. (In

Japanese). https://www.pref.kochi.lg.jp/doc/2018022700035/file_contents/file_20212184113656_1.pdf.

Accessed April 30, 2024.

|

|

9

|

Japan Medical Association: Japan medical

analysis platform. Regional Statistics: Kochi (In Japanese).

https://jmap.jp/cities/detail/pref/39. Accessed April

30, 2024.

|

|

10

|

Ministry of Internal Affairs and

Communications Fire and Disaster Management Agency: The State of

Emergency and Rescue Services, 2022 edition (In Japanese).

https://www.fdma.go.jp/publication/rescue/post-4.html.

Accessed April 30, 2024.

|

|

11

|

Fullman N, Yearwood J, Abay SM, Abbafati

C, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abebe Z, Abebo TA, Aboyans

V, et al: Measuring performance on the healthcare access and

quality index for 195 countries and territories and selected

subnational locations: A systematic analysis from the global burden

of disease study 2016. Lancet. 391:2236–2271. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ota K, Nishioka D, Katayama Y, Kitamura T,

Masui J, Ota K, Nitta M, Matsuoka T and Takasu A: Influence of the

COVID-19 outbreak on transportation of pregnant women in an

emergency medical service system: Population-based, ORION registry.

Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 157:366–374. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

El-Shabasy RM, Nayel MA, Taher MM,

Abdelmonem R, Shoueir KR and Kenawy ER: Three waves changes, new

variant strains, and vaccination effect against COVID-19 pandemic.

Int J Biol Macromol. 204:161–168. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kumar R, Yeni CM, Utami NA, Masand R,

Asrani RK, Patel SK, Kumar A, Yatoo MI, Tiwari R, Natesan S, et al:

SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and pregnancy-related

conditions: Concerns, challenges, management and mitigation

strategies-a narrative review. J Infect Public Health. 14:863–875.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Japanese Society for Reproductive

Medicine: Statement from the Japanese Society for Reproductive

Medicine on new coronavirus infection (COVID-19), 2020 (In

Japanese). http://www.jsrm.or.jp/announce/187.pdf. Accessed April

30, 2024.

|

|

16

|

Japan Surgical Society: Recommendations

for surgical procedures for patients with positive or suspected new

coronavirus, 2020 (In Japanese). https://jp.jssoc.or.jp/modules/aboutus/index.php?content_id=53.

Accessed April 30, 2024.

|

|

17

|

Komatsu H, Banno K, Yanaihara N and Kimura

T: Board Members of Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Prevention and practice during the COVID-19 emergency declaration

period in Japanese obstetrical/gynecological facilities. J Obstet

Gynaecol Res. 46:2237–2241. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nakagawa K, Umazume T, Mayama M, Chiba K,

Saito Y, Kawaguchi S, Morikawa M, Yoshino M and Watari H:

Feasibility and safety of urgently initiated maternal telemedicine

in response to the spread of COVID-19: A 1-month report. J Obstet

Gynaecol Res. 46:1967–1971. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mallampati DP, Talati AN, Fitzhugh C,

Enayet N, Vladutiu CJ and Menard MK: Statewide assessment of

telehealth use for obstetrical care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 5(100941)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Li W, Dong Y, Liu W, Tang Z, Sun C, Lowe

S, Chen S, Bentley R, Zhou Q, Xu C, et al: A deep belief

network-based clinical decision system for patients with

osteosarcoma. Front Immunol. 13(1003347)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Li W, Zhou Q, Liu W, Xu C, Tang ZR, Dong

S, Wang H, Li W, Zhang K, Li R, et al: A machine learning-based

predictive model for predicting lymph node metastasis in patients

with Ewing's Sarcoma. Front Med (Lausanne).

9(832108)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R,

Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, O'Brien P, Morris E,

Draycott T, Thangaratinam S, et al: Effects of the COVID-19

pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 9:e759–e772. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Molina RL, Tsai TC, Dai D, Soto M,

Rosenthal N, Orav EJ and Figueroa JF: Comparison of pregnancy and

birth outcomes before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw

Open. 5(e2226531)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Homma C, Hasegawa J, Nishimura Y, Furuya

N, Nakamura M and Suzuki N: Declaration of emergency state due to

COVID-19 spread in Japan reduced maternal transports without

reduction in preterm delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 161:854–860.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Watanabe T, Katata C, Matsushima S, Sagara

Y and Maeda N: Perinatal care preparedness in Kochi prefecture for

when a Nankai Trough earthquake occurs: Action plans and disaster

liaisons for pediatrics and perinatal medicine. Tohoku J Exp Med.

257:77–84. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|