1. Introduction

Children commonly present with acute pain that is

either localized or generalized in the body. The pain may

occasionally be underrated and thus inadequately treated with the

possible consequence of significant issues for the health of the

affected child. The revised International Association for the Study

of Pain defines pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional

experience associated with or resembling that associated with

actual or potential tissue damage (1). The clinical assessment of pain in

pediatric patients must include several aspects, such as the

psychological history of the child and their family, a thorough

physical examination, and when necessary, laboratory analyses and

radiological findings. Clinical indications should be drawn from

the quality, location, duration, frequency and intensity of the

pain. Pain is regarded as a symptom of an underlying condition, and

perceptions of pain may be felt in accordance with different

factors, such as the age, cognition, sex, previous pain

experiences, temperament and psychological attitude of each patient

(1). Pain has been temporally

distinguished as acute and chronic and arbitrarily defined as acute

when it lasts for 3 months and chronic when the duration is 6

months (2,3). Acute pain may also be referred to as

a painful episode that is transitory and only lasts until the

noxious stimulus ends or the underlying damage or pathological

event(s) have been removed. Acute pain may further be a temporal

manifestation of a chronic disorder.

Pain is a subjective experience (4). Despite the development and greater

awareness of instruments, guidelines, and educational and training

strategies, recent studies have shown that clinicians still do not

pay sufficient attention to pain management, particularly in

children. Inadequate clinical evaluations, inappropriate scale

measurements and the treatment of acute pain in various situations

have been clearly identified as contributing to this issue

(5). In children who are <2

years of age, the situation is more pronounced, as the pain, even

if treated, is sometimes managed with incorrect or inadequate

dosages (5). Acute pediatric pain

evaluations must include the pain quality, characteristics,

location, onset, duration, aggravating and alleviating factors, and

the impact on function (6-9).

In children and adolescents, the intensity and quality of pain may

be assessed using self-report measures, such as drawings, images of

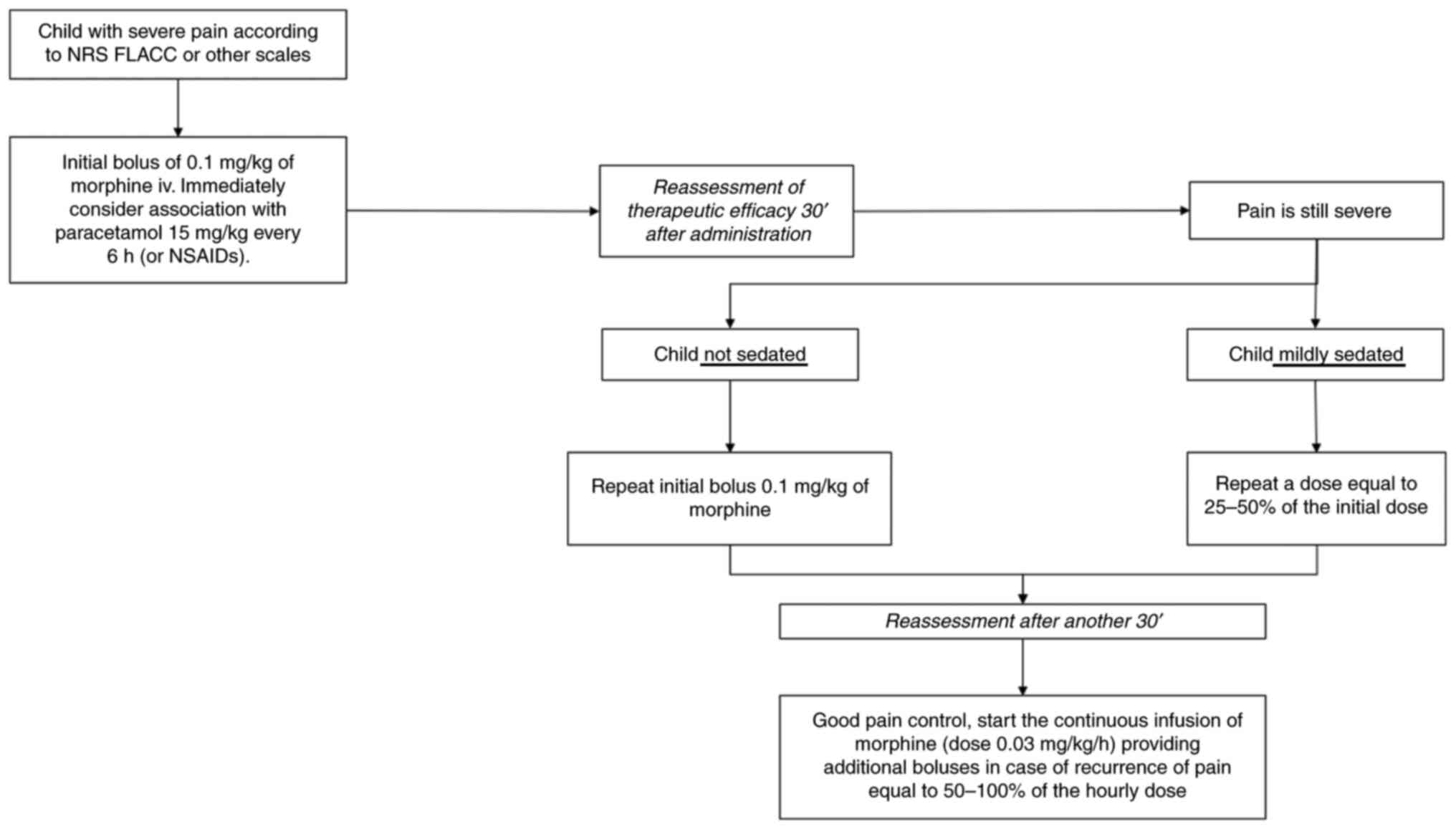

faces, graded color intensities and other systems (8). The aim of the present review was

therefore to report the modalities used to measure the presence and

grades of acute pain in children, and the different strategies to

approach and treat such pain in different clinical situations. A

flowchart for the management of children with severe pain is

presented in Fig. 1.

2. Literature search methods

A literature review was conducted by collecting

articles, including clinical trials, primary research articles and

reviews from online bibliographic databases (i.e., MEDLINE, Embase,

PubMed, Cochrane Central and Scopus) covering the period from

January, 2000 to December, 2022. The key words used for the search

were derived from medical subject heading terms, namely ‘pain and

children (pediatric)’, ‘pediatric’, ‘child’, ‘infant’, ‘toddler’ OR

pain therapeutic strategies (‘analgesic’ or ‘analgesia’) OR pain

pharmacological treatments OR opioid medications OR pain and

nonpharmacological therapies. Relevant studies were examined

manually and are included in the present reference list. As the

subject of the present study was notably wide, the literature data

that were included were those that were, in the authors' opinion,

more representative.

Once the initial results had been collected, two

reviewers analyzed the titles and abstracts and screened them for

the inclusion criteria, which were studies with any level of

evidence that reported clinical results published over the past 22

years (2000-2022). Comparative, cross-sectional, retrospective,

prospective and survey studies, case series, and case reports on

the pediatric population were included. All the articles written in

languages other than English were excluded. Articles that dealt

with different topics, had poor scientific methodologies, or were

without an accessible abstract were also excluded. In addition,

articles that did not match the inclusion criteria were ruled out.

After removing the duplicate records, the main search articles that

related to the study were included.

3. Acute pain in children

Diverse events cause acute pain in children, which

affects various body organs and requires treatment by different

types of specialists. Numerous clinical studies have addressed

scale measurements of pain and clinical trials for pain treatment.

However, to the best of our knowledge, no common agreement has been

reached on the methods to use to measure pain in children or

treatment strategies, although several options have been proposed

for each topic. The present literature review indicates that a wide

range of scales are used to measure acute pediatric pain, with

different options employed for pharmacological and

non-pharmacological treatment strategies.

The causes and treatment of acute pain are

significant challenges, particularly among children and

adolescents. Current guidelines recommend assessing and relieving

(1,3,8) pain

in all children in all instances; yet in clinical practice,

particularly in the pediatric population, management is suboptimal

and not completed (5). In a survey

of acute pain management in children that involved 929 Italian

pediatricians, Marseglia et al (10) reported the results obtained for

6,335 patients with a uniform distribution of different types of

acute pain. Pain was more frequently found to be of moderate

intensity (42.2%, P<0.001) and a short duration (within a few

days: 98.4%, P<0.001). Only 50.1% of the respondents used an

algometric scale to measure pain, and 60.5% always prescribed a

treatment. In the group of children with mild to moderate pain

(n=4,438), the most commonly used first-line nonopioid treatments

were ibuprofen (53.3%) and acetaminophen (44.4%) (10). In the authors' experience,

analgesics can be used without causing complications; however, the

side-effects of these analgesics should be taken into

consideration, as these can aggravate issues that already present

in patients with comorbidities. For example, non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cause gastric toxicity, which

adds to basic reflux, and a reduction in renal flow, which adds to

the poor intake of water. The hepatotoxic effect of paracetamol can

contribute to malnutrition and the effects of cytochrome inhibitor

drugs. Opioids can worsen constipation, nausea and dystonia and can

cause itching, which the child will not be able to scratch, as well

as urinary retention (globus vesicalis), particularly if the child

is receiving glycopyrrolate therapy.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a

step approach, with pain divided into mild, moderate and severe

(11). In the case of mild pain,

the suggested treatment is non-opioid medications. For moderate

pain, weak opioids should be used, with strong opioids used for

severe pain. The most difficult task in the evaluation is the

individuation of the pain condition and the application of the

appropriate therapy.

In the assessment of acute pain in children, among

the other key factors, are the evaluation of the grade of the pain

and the correct treatment required for its attenuation or

cessation.

4. Scales for pain grade measurement in

pediatric patients

Various tools are available to measure the grades of

acute pain in children. A list of scales to measure the properties

of self-reported pain intensity is presented in Table I. No single scale is advocated as

optimal for use with all types of pain or across the developmental

age span. Scales must be applied with due consideration of several

factors, including the age of the child, the clinical localization

and severity of the pain, and the cognitive and psychological

structure of the child (9,12-14).

In children with neurocognitive disabilities and in the context of

emergency rooms/urgent situations, the measurement of the severity

of pain becomes more complex and difficult. The

inability/difficulty of children to communicate verbally or

non-verbally, the presence of stereotyped or involuntary movements,

altered facial and body expressiveness, and sensory disabilities

may limit the validity of pain measurement.

| Table IAcute pain scales. |

Table I

Acute pain scales.

| Scale name | Type of scale | Age | Scoring system | Scale | Indications |

|---|

| Faces Pain Rating

Scale |

Self-evaluation | 4-8 years | Picture-based scale

where child select 1 of 6 faces to represent their pain

experience | 0-10 (0-3 mild, 4-6

moderate, 7-10 severe) | Cognitively

adequate child with motor impairment |

| Numerical Rating

Scale (NRS) | | >8 years | Ask the patient to

assign a number to their pain (0 no pain, 10 worst pain ever) | 0-10 (0-3 mild, 4-6

moderate, 7-10 severe) | Cognitively

adequate child without motor impairment |

| FLACC (Face Legs

Activity Cry Consolability) |

Hetero-valuation | 0-3 years | 5 Behaviour items

each scored from 0 to 2 to a total of 10 points | 0-10 (0-3 mild, 4-6

moderate, 7-10 severe) | |

| FLACC-R

(Revised) | | 2 months-7 years or

any age nonverbal or with intellectual impairment | Compared to ‘FLACC’

includes additional pain behaviours often found in children who are

non-verbal or with cognitive impairment | 0-10 (0-3 mild, 4-6

moderate, ≥7 severe) | |

| NCCPC-R

(Non-Communicating Children's Pain Checklist-Revised) | | 3-18 years | Scale with 30 total

items with 7 subscales (vocal, social, facial, activity, body and

limbs, physiological, and eating/sleeping) each item scored from 0

to 3 according to the frequency of its occurrence. | Total score of ≥7

indicates pain. | Children with

cognitive impairment, non-verbal or unable by age to provide pain

self-assessment |

| PPP (Pediatric Pain

Profile) | | 1-18 years | Two-part

individualized measure allowing caregivers to describe their

child's pain behaviours on good days and bad days and complete a

20-item measure scored on a 0-3 scale | Total score of ≥14

indicates clinically significant pain, 10-19 is mild, 20-29 is

moderate, 30-39 is severe, and >40 is very severe pain. | |

| EVENDOL (EValuation

ENfant DOuLeur) | | 0-7 years | Five items (vocal

or verbal expression, Facial expression, movements, postures,

interaction with the environment) evaluated at rest and at

mobilization, | Total score ranges

from 0 to 15. Treatment threshold ≥4 | |

| Color Analogue

Scale (CAS) | | 4-10 years | Gradations in

colour, area and length so as to easily associate scale positions

with diffused levels of pain intensity | The back of the

tool has a numerical rating scale providing means to assign a

numerical pain score between 1 and 10 cm in 0,25 cm increment | |

5. Therapeutic strategies

Various types of acute pediatric treatments are

available depending on the age of the patient, the intensity of the

pain, and the characteristics and types of organs affected. As the

topic is extremely wide, the present review summarizes the

treatment strategies more frequently used. The therapeutic

strategies can be divided into non-pharmacological techniques and

pharmacological drugs. The use of several other analgesics is not

considered (e.g., nitrous oxide, methoxyflurane, ketamine,

diamorphine) as this was beyond the scope of the present

review.

Non-pharmacological techniques

Research has shown that non-pharmacological options,

including physical and psychological strategies, may be helpful in

treating pain. Children may benefit from cognitive behavioral

strategies, such as the use of imagery or relaxation. The

application of non-pharmacological techniques has been employed to

control pain, stress, and anxiety in children and their parents

(9). The present review provides a

summary of some of the suggested non-pharmacological strategies

aimed at the attenuation or cessation of acute pain in children. In

their review of 39 trials with 3,394 participants, Uman et

al (15) examined the effects

of psychological interventions on needle-related procedural pain

and distress in children and adolescents aged 2-19 years. They

found strong evidence in support of distraction and hypnosis for

needle-related pain and distress in this population (15). Similarly, Accardi and Milling

(16) reported the effectiveness

of hypnosis in reducing procedure-related pain in children. A

systematic literature search on non-pharmacological interventions

used for pain management in children in emergency departments was

conducted by Wente (9). Among the

14 articles examined, distraction was used in 10 studies, sucrose

in two studies, cold application in one study, and parental holding

and positioning in one study. Furthermore, decreased pain, distress

and anxiety in the parent, child, and/or observer were noted when

these procedures were used (9).

Cognitive-behavioral strategies should be related to the age and

degree of cognitive development of the patient: The oral

administration of sucrose and glucose, kangaroo care, tactile

stimulation, rocking, singing and soft music, and an environment

with soft, fused lights can be effective for infants. For children

of school age, the application of cold spray, ice, hot moist packs,

massaging and pressure can be useful and satisfying. Furthermore,

the use of bandages, dressings and splints are other simple systems

that can be used to reduce pain symptoms and anxiety, as these

cover the view of the ‘wound’ that is causing psychophysical

distress in the child (2). A study

involving 98 children and 97 control children/parents examined the

beliefs of parents about pain and the efficacy of a parental

educational intervention on pain intensity in children and the

experience of pain-related unpleasantness at 24 h post-discharge

from the emergency department (17). According to the researchers, the

active participation of parents in their child's pain management

may be more effective than a passive educational intervention

(17). Music therapy has also been

shown to be a form of distraction that alleviates some types of

pain and distress experienced by children undergoing medical

procedures in a pediatric emergency department (18). In a previous comprehensive review

that included 13 studies and involved 778 patients, the effects of

music therapy and opioid treatment on pain anxiety among patients

who underwent orthopedic surgery were evaluated. Significant

differences were found between the two groups regarding the use of

music therapy to reduce pain; however, no statistically significant

differences were found in the use of opioids and physiological

variables between the two groups. The authors maintained that the

timing, duration, and type of music intervention can be modified in

relation to specific clinical settings and medical teams (19). A summary of the non-pharmacological

techniques used for pain management in children is presented in

Table II.

| Table IINon-pharmacological therapy. |

Table II

Non-pharmacological therapy.

| Type of method | Age |

|---|

| Physical

methods | |

|

Comforting

touch (cuddles, stroking, holding) | All ages |

|

Comfort

positioning | All ages |

|

Cutaneous

stimulation | >1 months |

|

Pressure/massage | All ages |

|

Hot/cold

treatments | All ages |

|

Pacifier and

sucrose solution | <1 years |

|

Cognitive-comportamental methods | |

|

Information/communication | >6 years |

|

Psychological

preparations | >6 years |

|

Direct

involvement in pain management/assessment | >6 years |

|

Distraction

tools (music, videos, apps, toys with light/sounds) | All ages |

|

Desensitization | >2 years |

|

View/imagery

(story-telling, guided imagery, favor activity) | >6 years |

|

Relaxation

(deep breathing, music, muscles relaxing) | All ages |

|

Breathing

out/controlled breathing | Teenagers |

Criticism has been expressed as regards the use of

non-pharmacological treatments in the context of acute pediatric

pain where pharmacological, physical (splint, ice) and

psychological (distraction, breathing) treatments may be more

effective. In addition, the literature provides evidence of the

difficulties faced by nurses in applying non-pharmacological

treatments due to inadequate cooperation from physicians, the heavy

workloads of nurses and multiple responsibilities, the low ratio of

nurses per patient, and the unfavorable attitudes of nurses to

non-pharmacological pain management (20).

Pharmacological strategies

Pharmacological therapies are the most commonly used

types of treatments for any type of pain. The drugs commonly

utilized, as well as the routes of administration, doses and

indications on their use are summarized in Table III.

| Table IIIPharmacological therapies for acute

pain. |

Table III

Pharmacological therapies for acute

pain.

| Drug | Route of

administration | Single dose | Maximum dose | Indications |

|---|

| Non-opioids | | | | |

|

Paracetamol | Per os | 10-15 mg/kg, every

4-6 h | 60-75 mg/kg/die (4

g/die) | From birth |

| | Rectal | 15-20 mg/kg, every

4-6 h | 60-90

mg/kg/die | |

| | i.v. | Per os | 90

g/kg/die | |

|

NSAIDs | | | | |

|

Ibuprofen | Per os | 5-10 mg/kg, every

6-8 h | 20-30

mg/kg/die | >3 months |

|

Ketoprofen | Per os | 1-3 mg/kg, every

8-12 h | 4-9 mg/kg/die | >6 years |

|

Ketorolac | Per os | 0.5 mg/kg, every

6-8 h | 3 g/kg/die | >16 years |

|

Naproxen

sodium | Per os | 1 mg/kg, every 8

h | 3 g/kg/die | >14 years |

|

Acetylsalicylic

acid | i.v. | 5-10 mg/kg, every

8-12 h | 20 g/kg/die | Not indicated in

pediatric age. If necessary >2 years |

| Opioids | Per os

(i.v.) | 10 mg/kg, every 6-8

h | 80 g/kg/die | >16 years |

|

Weak | | | | |

|

Codeine | Per os or

rectal | 0.5-1 mg/kg, every

6-8 h | 240 mg/die | >12 years |

|

Tramadol

hydrochloride | Per os | 1-2 mg/kg, every

6-8 h | 400 mg/die | >1 year |

|

Strong | | | | |

|

Fast-release

morphine sulfate | i.v. | 0.15-0.3 mg/kg,

every 4 h | | >1 year |

|

Morphine

hydrochloride | i.v. | Bolus 0.05-0.1

mg/kg, every 2-4 h | 5 mg/dose | From birth |

| | | CI 0.02-0.03

mg/kg/h | | |

|

Fentanyl | Intra nasal

injections | 1-2 µg/kg/dose

(repeatable after 30-60 min) | 100 µg | |

| | i.v. | Bolus 0.001-0.002

mg/kg; CI 0.001 mg/kg/h | | >2 years |

Non-opioid medications. The non-opioid pain

medications most commonly used are NSAIDs, which act via their

inhibitory actions on cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 enzymes. COX-2 enzymes

facilitate the production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins; thus,

prostaglandin production is inhibited to obtain an analgesic

effect. Among the most commonly used NSAIDs is ibuprofen. Other

COX-2 inhibitors, such as indomethacin, meloxicam and Celebrex, are

more frequently used to treat inflammatory and rheumatological

disorders than acute pain (20,21A previous randomized controlled

trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen and codeine treatment for acute

pain in children with musculoskeletal trauma conducted by Clark

et al (21) involved 336

pediatric patients with 100 children in each treatment group.

According to the authors of that study, ibuprofen provided the

optimal analgesic effect of the three medications studied. In

another study, a group of children presenting with uncomplicated

extremity fractures was treated in a randomized trial with the oral

administration of either morphine or ibuprofen (22). In that trial, 66 children were in

the morphine group and 68 in the ibuprofen group. No significant

differences in analgesic efficacy were reported between the groups,

although morphine was associated with a significantly greater

number of adverse effects. The authors of that study maintained

that ibuprofen remains safe and effective for outpatient pain

management in children with uncomplicated fractures (22). In another randomized clinical trial

performed by Chang et al (23), of 411 patients with acute extremity

pain (mean score, 8.7 on an 11-point numerical rating scale) in an

emergency department, no significant differences in pain reduction

at 2 h were found. The main pain scores decreased by 4.3 with

ibuprofen and acetaminophen, 4.4 with oxycodone and acetaminophen,

3.5 with hydrocodone and acetaminophen, and 3.9 with codeine and

acetaminophen. According to the authors of that study, the

analgesic effects of NSAIDs were equally efficacious as opioids

when treating musculoskeletal pain in adult patients (23).

As is well known, the use of ibuprofen is not

recommended for patients with hemorrhagic pathologies, significant

dehydration, gastrointestinal disorders and impaired renal

function. Jelinek (24)

demonstrated that the intravenous administration of ketorolac

exhibited an equivalent efficacy in reducing moderate to severe

pain as intravenous morphine, although with fewer side-effects.

Marzuillo et al (25)

reviewed the pharmacokinetics of ketorolac and confirmed its

efficacy without severe side-effects, if used for a short period of

time. Recently, a pilot single central randomized controlled trial

demonstrated that ketorolac had comparable results to morphine when

used in children aged 6-17 years with suspected appendicitis

(26). The use of ketorolac

sublingually as a valid alternative in the absence of intravenous

access was also suggested (26).

Neri et al (27)

demonstrated that sublingual ketorolac and tramadol were equally

effective. In cases of suspected bone fractures, studies have shown

that sublingual ketorolac and tramadol are effective analgesics for

pain management in children aged 4-17 years (25,26).

Paracetamol has been cited in numerous studies as

the first-line analgesic agent in emergency departments. Its

efficacy is valuable at the correct dose (15 mg/kg) in the

treatment of mild to moderate pain. It is characterized by its

rapid action and the possibility of different routes of

administration (28). A previous

meta-analysis revealed that the safety and tolerability profiles of

paracetamol and ibuprofen were similar in terms of their efficacy

for both pain and fever, and they were rarely associated with

severe side-effects (28). In

instances of mild or moderate pain, it is preferable to administer

paracetamol per os to achieve fairly rapid action and

excellent tolerance in the majority of children. By contrast, the

rectal route is burdened by slow absorption and unpredictable

efficacy both with respect to action time and analgesic capacity

(29). In a multicenter emergency

department study in 2018, Benini et al (7) found that both paracetamol and

ibuprofen were inappropriately used in 83 and 63% of pediatric

cases, respectively.

Ketamine, a drug that blocks the effects of

glutamate, has been shown to be an effective analgesic in children

when administered at sub-dissociative doses (30). Back pain, headache, extremity or

musculoskeletal pain, acute abdominal pain and renal colic are

controlled by the intravenous administration of ketamine when used

appropriately (31,32). In recent years, two systematic

reviews and meta-analyses demonstrated that ketamine was

non-inferior to opioid medications for acute pain management, as it

had a similar analgesic effect and safety profile (33,34).

Opioid medications. Opioid infusion is

usually indicated for patients with chronic pain. OF note, a bolus

of an intravenous opioid is advised for patients with sudden-onset

severe pain or reserved for breakthrough pain for patients who are

already receiving opioid infusions. Researchers have recommended

that the starting opioid in opioid-naïve patients should be

morphine or hydromorphone (30).

Typically, immediate-release oral opioids are ordered for pain at

intervals of 3-4 h to minimize breakthrough pain and opioid

side-effects (30). Additional

smaller doses can be administered every 2 h for breakthrough doses.

In general, oral use is preferred over intravenous administration,

except in cases of poor absorption or an inability to administer

drugs enterally (i.e., colitis, mucositis, vomiting). The

sublingual route of administration is safe and efficacious both for

ketorolac and opioids (34,35).

In the trauma setting, intranasal sufentanil or diamorphine

administration have both been reported as highly efficacious in the

treatment of severe pain (36,37).

6. Conclusion

The role of the pediatricians in the treatment of

acute pain is extremely complex due to the poor collaboration of

and difficulties encountered by the children and their parents to

correctly indicate the duration, intensity and localization of the

pain. The task of pediatricians consists of carefully evaluating

the underlying cause for acute pain in children to consequently

administer appropriate treatment. The list of methodologies used to

reveal the scales of acute pain and the type of treatment to be

used for specific causes of acute pain is wide. Thus, treatment

needs to be carried out according to the duration, localization and

severity of the pain, reflecting the experience of the single

pediatric specialist.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

PP, RF, LM, MCF and ADN conceived and designed the

study. GT and ADS performed the literature search. CM, LS and MCF

analyzed the data obtained from the literature. PP, AP and RF wrote

the manuscript. All authors (ADN, LS, MCF, GT, CM, ADS, SS, AP, MC,

RF, LM and PP) were involved in the preparation of the final draft

and in the revision of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB,

Flor H, Gibson S, Keefe FJ, Mogil JS, Ringkamp M, Sluka KA, et al:

The revised international association for the study of pain

definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain.

161:1976–1982. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Coda BA and Bonica JJ: General

considerations of acute pain. In: Loeser JD, Butler SH, Chapman CR

and Turk DC (eds) Bonica's management of pain, 3rd edition.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp222-240,

2001.

|

|

3

|

Olson KA: Pain in children. Children can

experience a wide variety of painful conditions-from migraine

headaches to growing pains. Pract Pain Manag. 15:1–18. 2015.

|

|

4

|

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee

on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on

Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. The assessment and

management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents.

Pediatrics. 108:793–497. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Mathews L: Pain in children: Neglected,

unaddressed and mismanaged. Indian J Palliat Care. 17

(Suppl):S70–S73. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ferrante P, Cuttini M, Zangardi T,

Tomasello C, Messi G, Pirozzi N, Losacco V, Piga S and Benini F:

PIPER Study Group. Pain management policies and practices in

pediatric emergency care: A nationwide survey of Italian hospitals.

BMC Pediatr. 13(139)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Benini F, Castagno E, Barbi E, Congedi S,

Urbino A, Biban P, Calistri L and Mancusi RL: Multicentre emergency

department study found that paracetamol and ibuprofen were

inappropriately used in 83 and 63% of paediatric cases. Acta

Paediatr. 107:1766–1774. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gai N, Naser B, Hanley J, Peliowski A,

Hayes J and Aoyama K: A practical guide to acute pain management in

children. J Anesth. 34:421–433. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wente SJK: Nonpharmacologic pediatric pain

management in emergency departments: A systematic review of the

literature. J Emerg Nurs. 39:140–150. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Marseglia GL, Alessio M, Da Dalt L,

Giuliano M, Ravelli A and Marchisio P: Acute pain management in

children: A survey of Italian pediatricians. Ital J Pediatr.

45(156)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ventafridda V, Saita L, Ripamonti C and De

Conno F: WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain.

Int J Tissue React. 7:93–96. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Birnie KA, Hundert AS, Lalloo C, Nguyen C

and Stinson JN: Recommendations for selection of self-report pain

intensity measures in children and adolescents: A systematic review

and quality assessment of measurement properties. Pain. 160:5–18.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Stinson JN, Kavanagh T, Yamada J, Gill N

and Stevens B: Systematic review of the psychometric properties,

interpretability and feasibility of self-report pain intensity

measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents.

Pain. 125:143–157. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bulloch B, Garcia-Filion P, Notricia D,

Bryson M and McConahay T: Reliability of the color analog scale:

Repeatability of scores in traumatic and nontraumatic injuries.

Acad Emerg Med. 16:465–469. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ and

Kisely SR: Psychological interventions for needle-related

procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev: CD005179, 2006.

|

|

16

|

Accardi MC and Milling LS: The

effectiveness of hypnosis for reducing procedure-related pain in

children and adolescents: A comprehensive methodological review. J

Behav Med. 32:328–339. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

LeMay S, Johnston C, Choinière M, Fortin

C, Hubert I, Fréchette G, Kudirka D and Murray L: Pain management

interventions with parents in the emergency department: A

randomized trial. J Adv Nurs. 66:2442–2449. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hartling L, Newton AS, Liang Y, Jou H,

Hewson K, Klassen TP and Curtis S: Music to reduce pain and

distress in the pediatric emergency department: A randomized

clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 167:826–835. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Patiyal N, Kalyani V, Mishra R, Kataria N,

Sharma S, Parashar A and Kumari P: Effect of music therapy on pain,

anxiety, and use of opioids among patients underwent orthopedic

surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus.

13(e18377)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zeleke S, Kassaw A and Eshetie Y:

Non-pharmacological pain management practice and barriers among

nurses working in debre tabor comprehensive specialized hospital,

ethiopia. PLoS One. 16(e0253086)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, Gaboury I

and Passi B: A randomized, controlled trial of acetaminophen,

ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with

musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 119:460–467. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Poonai N, Bhullar G, Lin K, Papini A,

Mainprize D, Howard J, Teefy J, Bale M, Langford C, Lim R, et al:

Oral administration of morphine versus ibuprofen to manage

postfracture pain in children: A randomized trial. CMAJ.

186:1358–1363. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP

and Baer J: Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid

analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: A

randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 318:1661–1667. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Jelinek GA: Ketorolac versus morphine for

severe pain. Ketorolac is more effective, cheaper, and has fewer

side effects. BMJ. 321:1236–1237. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Marzuillo P, Calligaris L, Amoroso S and

Barbi E: Narrative review shows that the short-term use of

ketorolac is safe and effective in the management of

moderate-to-severe pain in children. Acta Paediatr. 107:560–567.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Eltorki M, Busse JW, Freedman SB, Thompson

G, Beattie K, Serbanescu C, Carciumaru R, Thabane L and Ali S:

Intravenous ketorolac versus morphine in children presenting with

suspected appendicitis: A pilot single-centre non-inferiority

randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 12(e056499)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Neri E, Maestro A, Minen F, Montico M,

Ronfani L, Zanon D, Favret A, Messi G and Barbi E: Sublingual

ketorolac versus sublingual tramadol for moderate to severe

post-traumatic bone pain in children: A double-blind, randomised,

controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 98:721–724. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kanabar DJ: A clinical and safety review

of paracetamol and ibuprofen in children. Inflammopharmacology.

25:1–9. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mak WY, Yuen V, Irwin M and Hui T:

Pharmacotherapy for acute pain in children: Current practice and

recent advances. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 12:865–881.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chumpitazi CE, Chang C, Atanelov Z,

Dietrich AM, Lam SHF, Rose E, Ruttan T, Shahid S, Stoner MJ, Sulton

C, et al: Managing acute pain in children presenting to the

emergency department without opioids. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians

Open. 3(e12664)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Schwenk ES, Viscusi ER, Buvanendran A,

Hurley RW, Wasan AD, Narouze S, Bhatia A, Davis FN, Hooten WM and

Cohen SP: Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine

infusions for acute pain management from the American society of

regional anesthesia and pain medicine, the American academy of pain

medicine, and the American society of anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth

Pain Med. 43:456–466. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Majidinejad S, Esmailian M and Emadi M:

Comparison of intravenous ketamine with morphine in pain relief of

long bones fractures: A double blind randomized clinical trial.

Emerg (Tehran). 2:77–80. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Karlow N, Schlaepfer CH, Stoll CRT,

Doering M, Carpenter CR, Colditz GA, Motov S, Miller J and Schwarz

ES: A systematic review and meta-analysis of ketamine as an

alternative to opioids for acute pain in the emergency department.

Acad Emerg Med. 25:1086–1097. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Balzer N, McLeod SL, Walsh C and Grewal K:

Low-dose ketamine for acute pain control in the emergency

department: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med.

28:444–454. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Díaz-Chávez EP, Medina-Chávez JL,

Avalos-González J, Hernández-Moreno JJ, Cabrera-Mendoza AU and

Trujillo-Hernández B: Comparison of sublingual ketorolac vs IV

metamizole in the management of pain after same-day surgery. Cir

Cir. 77:45–49. 2009.PubMed/NCBI(In Spanish).

|

|

36

|

Minkowitz HS, Singla NK, Evashenk MA,

Hwang SS, Chiang YK, Hamel LG and Palmer PP: Pharmacokinetics of

sublingual sufentanil tablets and efficacy and safety in the

management of postoperative pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 38:131–139.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Borland M, Jacobs I, King B and O'Brien D:

A randomized controlled trial comparing intranasal fentanyl to

intravenous morphine for managing acute pain in children in the

emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 49:335–340. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|