Introduction

Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) is an uncommon

condition that occurs in urinary catheterized patients with urinary

tract infection (UTI). It was first described in 1978, though a

possible mechanism was not established until 1988 (1,2). With

regard to the mechanism, tryptophan is metabolized by intestinal

bacteria, after which the by-product indoxyl sulfate is expelled

into the urine and digested into indoxyl by sulfatases/phosphatases

produced by certain bacteria including Escherichia coli (E.

coli), Proteus mirabilis, Morganella morganii (M. morganii),

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Providencia stuartii, Providencia

rettgeri and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2,3). This

indoxyl may convert into indigo and indirubin in the urine drainage

bag and create purple discoloration (2).

A higher prevalence of PUBS has been reported in

females and in patients with alkaline urine, an indwelling urinary

catheter and constipation (3). The

majority of patients with PUBS are catheterized due to significant

disability, typically being chair-bound or bed-bound elderly

patients (3). In previous years, PUBS

has been considered to be a benign syndrome rather than a disease

with lethal potential, and appropriate empirical oral antibiotics

including ciprofloxacin remain to be suggested for its treatment

(3). To the best of our knowledge,

there have been no previous studies on the clinicopathological or

epidemiological trends of PUBS; therefore, the current study

retrospectively reviewed PUBS cases for characteristic analysis. A

systematic review of PUBS cases reported between October 1980 and

August 2016 was conducted, in which data regarding patient age and

gender, comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, uremia, constipation and

residence in long-term care facility), vital signs (presence or

absence of fever), laboratory tests results [seral white blood cell

(WBC) count, urine pH value] and mortality were evaluated. This

aimed to identify trends in the epidemiology of PUBS. Through the

systematic approach, the different clinicopathological aspects and

general trends of PUBS were determined.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and article

selection

A systematic review was designed to investigate

clinicopathological characteristics in PUBS, including patient age

and gender, urine pH value, presence of fever, shock (defined by

hypotension), WBC count, constipation and comorbidities (diabetes

mellitus, uremia), urine culture bacteriology, rates of patients in

long-term care units and mortality. To determine the trends in the

epidemiology of PUBS, the differences in these characteristics over

three decades were also analyzed. A search was performed for

articles in the PubMed database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) including the

word ‘purple urine bag syndrome’ in the title, published in the

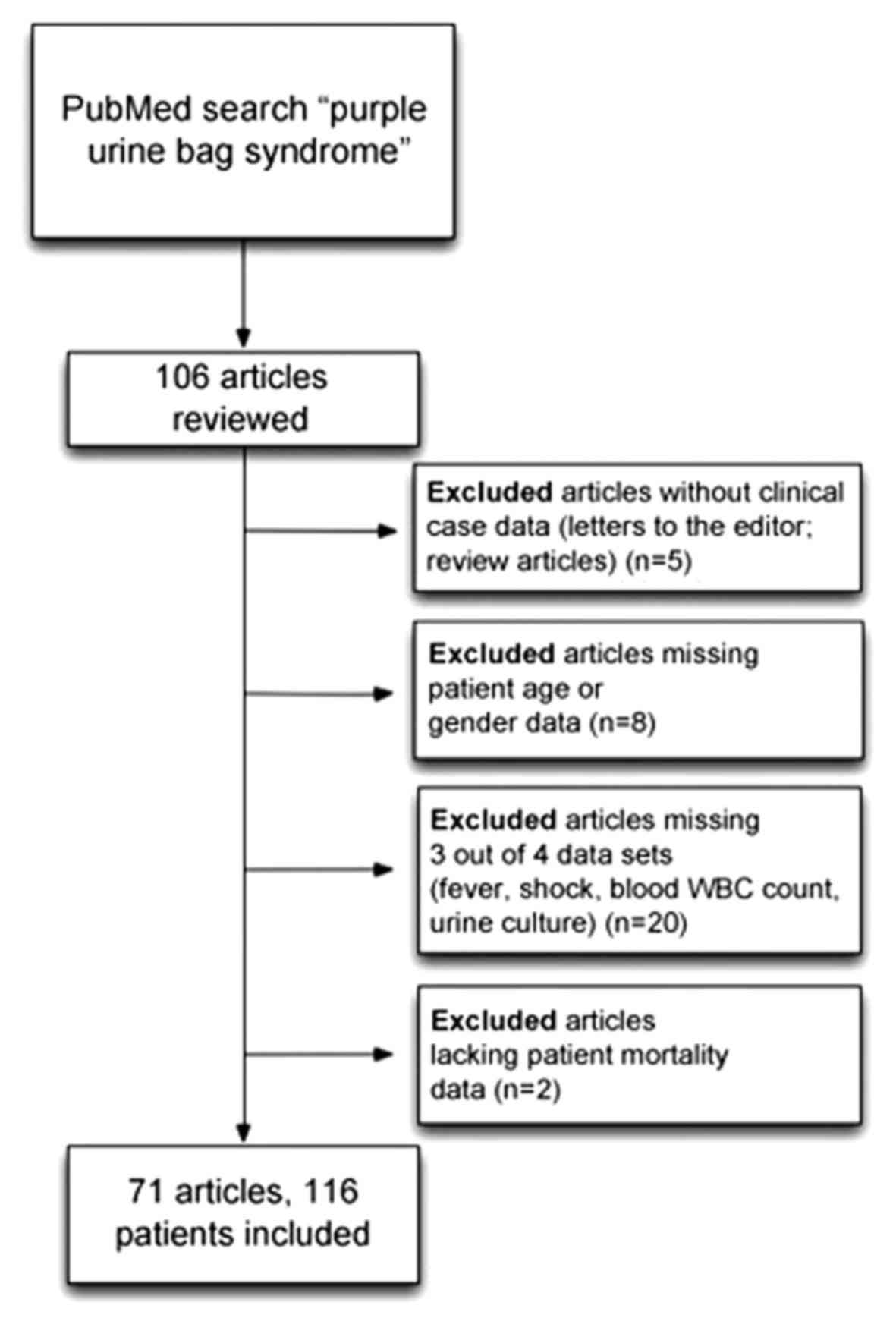

period from January 1, 1980 to September 1, 2016. A total 106

relevant articles were identified. Of these, 33 articles were

excluded owing to ineligibility or lack of essential information.

The full exclusion criteria are depicted in (Fig. 1). Therefore, 71 articles with patient

data on 116 cases (4–74) were collected for review (Table I). The articles were divided into

three groups by publication year: 1991 to 2000, 2001 to 2010 and

2011 to 2016. The following clinical features were defined as: i)

Elderly patients: age ≥65 years old; ii) fever: body temperature

≥38°C; iii) hypotension: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg or

diastolic blood pressure <60 mmHg.

| Table I.Case demongraphics of the 71 articles

included in the present study. |

Table I.

Case demongraphics of the 71 articles

included in the present study.

| Author | Year | Language | Country | Cases | Mean age ± SD

(years old) | Refs. |

|---|

| Umeki | 1993 | Japanese | Japan | 4 | 80±1.41 | (4) |

| Nobukuni et

al | 1995 | Japanese | Japan | 5 | 60.4±10.61 | (5) |

| Al-Jubouri and

Vardhan | 2001 | English | UK | 1 | 85 | (6) |

| Ihama and

Hokama | 2002 | English | Japan | 1 | 93 | (7) |

| Vallejo-Manzur

et al | 2005 | English | USA | 1 | 72 | (9) |

| Wang et

al | 2005 | English | Taiwan | 2a | 61 | (10) |

| Rohaut et

al | 2005 | French | France | 1 | 81 | (8) |

| Achtergael et

al | 2006 | English | Belgium | 1 | 77 | (11) |

| Beunk et

al | 2006 | English | UK | 1 | 84 | (12) |

| Tang | 2006 | English | Hong Kong | 2 | 76±8.49 | (13) |

| Su et

al | 2007 | English | Taiwan | 1 | 61 | (20) |

| Nair et

al | 2007 | English | UK | 1 | 83 | (18) |

| Bar-Or et

al | 2007 | English | USA | 1 | 68 | (14) |

| Gautam et

al | 2007 | English | India | 1 | 70 | (15) |

| Ting et

al | 2007 | English | Taiwan | 1 | 72 | (21) |

| Lazimy et

al | 2007 | French | France | 1 | 74 | (17) |

| Harun et

al | 2007 | English | Brunei | 2 | 60±21.21 | (16) |

| Pillai et

al | 2007 | English | UK | 1 | 76 | (19) |

| Lin et

al | 2008 | English | Taiwan | 10 | 75.3±2.12 | (24) |

| Chiang et

al | 2008 | Chinese | Taiwan | 1 | 73 | (22) |

| Chung et

al | 2008 | English | Taiwan | 1 | 85 | (23) |

| Vidarsdottir et

al | 2008 | Icelandic | Iceland | 1 | 72 | (27) |

| Shiao et

al | 2008 | English | Taiwan | 14 | 80.9±11.5 | (26) |

| Muneoka et

al | 2008 | Japanese | Japan | 6 | 87.7±16.26 | (25) |

| Tasi et

al | 2009 | English | Taiwan | 2 | 64±19.8 | (30) |

| Al-Sardar and

Haroon | 2009 | English | UK | 1 | 82 | (28) |

| Wu et

al | 2009 | English | Taiwan | 1 | 95 | (32) |

| van Iersel and

Mattijssen | 2009 | English | Netherlands | 1 | 72 | (31) |

| Pillai et

al | 2009 | English | Singapore | 1 | 69 | (29) |

| Ferrara et

al | 2010 | English | Italy | 1 | 81 | (33) |

| Hirzallah and

D'Souza | 2010 | English | Jordan | 1 | 78 | (34) |

| Siu and

Watanabe | 2010 | English | USA | 1 | 48 | (35) |

| Su et

al | 2010 | English | Taiwan | 1 | 81 | (36) |

| Kang et

al | 2011 | English | Korea | 3 | 74.7±0 | (37) |

| Keenan and

Thompson | 2011 | English | USA | 1 | 97 | (38) |

| Khan et

al | 2011 | English | USA | 1 | 39 | (39) |

| Peters et

al | 2011 | English | Australia | 1 | 82 | (40) |

| Zeier et

al | 2011 | English | Singapore | 1 | 75 | (41) |

| Bocrie et

al | 2012 | English | France | 1 | 87 | (42) |

| Cantaloube et

al | 2012 | French | France | 2 | 81.5±0.71 | (43) |

| Dominguez Alegria

et al | 2012 | Spanish | Spain | 1 | 78 | (44) |

| Meekins et

al | 2012 | English | USA | 1 | 67 | (45) |

| Montasir and

Mustaque | 2013 | English | Bangladesh | 1 | 86 | (46) |

| Bhattarai et

al | 2013 | English | USA | 1 | 87 | (47) |

| Canavese et

al | 2013 | English | Italy | 3 | 79±19.52 | (48) |

| Duff | 2013 | English | USA | 1 | 57 | (49) |

| Iglesias Barreira

et al | 2013 | Spanish | Spain | 2 | 93.5±2.12 | (50) |

| Mohamad and

Chong | 2013 | English | Brunei | 1 | 78 | (51) |

| Ungprasert et

al | 2013 | English | USA | 1 | 44 | (52) |

| Wolff et

al | 2013 | French | France | 1 | 90 | (53) |

| Yaqub et

al | 2013 | English | Pakistan | 1 | 83 | (54) |

| Agapakis et

al | 2014 | English | Greece | 1 | 82 | (55) |

| Chassin-Trubert

et al | 2014 | Spanish | Chile | 1 | 72 | (56) |

| Delgado et

al | 2014 | English | Mexico | 1 | 60 | (57) |

| Hloch et

al | 2014 | Czech | Czech Republic | 1 | 73 | (58) |

| Restuccia and

Blasi | 2014 | English | Italy | 1 | 81 | (59) |

| Sheehan | 2014 | English | USA | 1 | 80 | (60) |

| Abubacker et

al | 2015 | English | India | 1 | 36 | (61) |

| Alex et

al | 2015 | English | India | 1 | 83 | (62) |

| Karim et

al | 2015 | English | USA | 1 | 83 | (63) |

| Kenzaka | 2015 | English | Japan | 1 | 72 | (64) |

| Mohamed Faisal

et al | 2015 | English | Malaysia | 1 | 68 | (65) |

| Mondragon-Cardona

et al | 2015 | English | Colombia | 1 | 71 | (66) |

| Neweling and

Janssens | 2015 | German | Germany | 1 | 78 | (67) |

| Redwood et

al | 2015 | English | USA | 1 | 90 | (68) |

| Van Keer et

al | 2015 | English | Belgium | 2 | 80.5±0.71 | (69) |

| Demelo-Rodriguez

et al | 2016 | English | Spain | 1 | 83 | (70) |

| Faridi et

al | 2016 | English | India | 1 | 76 | (71) |

| Richardson-May | 2016 | English | UK | 1 | 94 | (72) |

| Sriramnaveen et

al | 2016 | English | India | 1 | 85 | (73) |

| Tul Llah et

al | 2016 | English | USA | 1 | 52 | (74) |

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed with SPSS statistical software

for Windows, version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Values are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical

χ2 tests were performed and the threshold for

significance was set at P<0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Description of the selected

articles

In the present study, 106 relevant articles were

retrieved. Following application of the inclusion and exclusion

criteria, 71 eligible articles (4–74) were

selected (57 in English, 4 in French, 3 in Spanish, 3 in Japanese,

1 in Chinese, 1 in German, 1 in Icelandic and 1 in Czech; Fig. 1 and Table

I). All the selected articles were images in clinical medicine,

individual case reports or serial case reports. The 71 articles

included a total of 116 PUBS cases aged from 36 to 100 years old

with a mean age ± standard deviation of 75.6±12.8 years. Of these,

47 cases were male (40.5%) and 69 were female (59.5%). Of these, 98

cases (84.5%) were elderly (≥65 years old).

Clinical characteristics in PUBS

The mean age of the patients was 75.6 years old, and

PUBS was more commonly observed in females than in males (1.5:1

ratio). As PUBS is associated with infectious pathology, mean WBC

was determined for the cases, which was elevated to 12,242

cells/µl. Only 11.8% of cases presented with fever, and 8.6% of

cases with shock. There were 6.9% of cases with acidic urine

(pH<7), while the remaining cases (93.1%) had urine pH>7. The

majority of cases (69.8%) had constipation, and 58.3% lived in

long-term care units. Regarding chronic co-morbidity, 19.2% of

cases had diabetes mellitus and 18.8% were uremic patients. Overall

mortality rate was 6.8%, thus indicating that PUBS may be

associated with patients' mortality and not always a benign

process.

Clinical characteristics in trend per

decade of PUBS cases

Regarding patient age, urine pH value, the presence

of fever, shock or uremia, a history of diabetes, and residence in

a long-term care unit, there were no significant changes over

subsequent decades among the PUBS cases (Table II). However, an increase in WBC count

from 2001–2010 to 2011–2016 (P=0.002; Table II), and in the male: female ratio

with each decade (P=0.018; Table I

and Fig. 2) were identified. Notably,

WBC count reached 17,060±14,480 cells/µl in the most recent five

years. Conversely, decreases in constipation rates (P=0.011;

Table II) and mortality rates

(P=0.001; Table II and Fig. 3) were also identified over the

subsequent decades. These decreasing rates may be attributed to

advancements in antibiotic treatment and the application of early

goal-directed-therapy (EGDT).

| Table II.Comparisons of purple urine bag

syndrome cases (n=116) over the last three decades. |

Table II.

Comparisons of purple urine bag

syndrome cases (n=116) over the last three decades.

|

|

| Decade, mean±SD or

% (total cases, n) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | Total period, mean

± SD or % (total cases, n) | 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | 2011–2016 | P-value

(two-tailed) |

|---|

| Age | 75.6±12.8

(116) | 69.1±13.1 (9) | 75.9±11.3 (59) | 75.8±16.8 (48) | 0.857 |

| Mean WBC count,

cells/µl | 12,242.7±10,661.5

(27) | NA | 9,203.3±3,736.7

(15) | 17,060.0±14,480.4

(12) | 0.002 |

| Urine pH value | 8.0±0.9 (72) | 8.1±0.7 (6) | 8.0±0.9 (36) | 8.0±1.1 (30) | 0.368 |

| Male: female | 47:69 (116) | 2:7 (9) | 22:39 (61) | 23:23 (46) | 0.018 |

| Fever | 12.1 (14/116) | 22.2 (2/9) | 9.8 (6/61) | 13.0 (6/46) | 0.360 |

| Shock | 8.6 (10/116) | 0.0 (0/9) | 9.8 (6/61) | 8.7 (4/46) | 0.418 |

| Constipation | 69.8 (44/63) | 100.0 (4/4) | 68.4 (26/38) | 66.7 (14/21) | 0.011 |

| Diabetes

mellitus | 19.2 (19/99) | 11.1 (1/9) | 25.6 (11/43) | 14.9 (7/47) | 0.266 |

| Uremia | 18.8 (21/112) | 11.1 (1/9) | 20.0 (12/60) | 18.6 (8/43) | 0.267 |

| Long-term care

unit | 58.3 (35/60) | NA | 60.0 (27/45) | 53.3 (8/15) | 0.057 |

| Mortality | 6.8 (8/116) | 11.1 (1/9) | 8.2 (5/61) | 4.3 (2/46) | 0.001 |

Bacteriology statistics

Bacterial species identified in urine cultures of

the PUBS patients are listed in Table

II. Culture results were not available for 9 cases, and there

was no bacteria growth for 2 cases. Among the 105 patients with

positive results, 3 patients yielded unidentified mixed organisms.

The top five most common bacterial species identified were E.

coli., Enterococcus spp., Proteus spp., M. morganii and

Klebsiella spp.

Discussion

It is well established that urinary tract infection

(UTI) may occur at variable ages, while PUBS is commonly observed

in elderly compared with non-elderly patients (3), as in the present report (84.5 vs.

15.5%). As we know, PUBS can be observed in sepsis of asymptomatic

bacteriuria (ABU) or CA-UTI.

The mechanism of PUBS originates from the dietary

digestion and absorption of tryptophan in the bowel. Bacteria in

the intestine metabolize the tryptophan to indole, and further

hepatic enzymes form the conjugate indoxyl sulfate for secretion

into urine by the kidneys. In the urinary tract, gram-negative

bacteria phosphatases and sulfatases metabolize the indoxyl sulfate

to indoxyl, and through oxidation, this may convert to indigo and

indirubin (2). For patients with

indwelling catheters, blue indigo deposited on the urine drainage

bag surface and red indirubin dissolved in the urine mixes into a

purple discoloration (2). A previous

study demonstrated that not all bacterial organisms of the same

species produce the phosphatase and sulfatase enzymes (2). Based on the above mechanism, bacteriuria

should be present in all patients with PUBS, which should be

diagnosed as ABU for those without clinical symptoms or signs

including fever or shock. A case control study reported that

bacterial counts in urine were significantly higher (by 1 to 2

logs) in patients with PUBS compared with those without the

syndrome, thus suggesting that a higher bacterial load in the urine

is an important factor leading to PUBS (75).

Regarding gender, females are generally more

vulnerable to UTI and PUBS, and female gender has been previously

considered a risk factor of catheter-associated (CA)-UTI among

urinary catheterized patients (76,77). In

the present study, the number of PUBS cases became equal between

the genders within the most recent 5 years. A similar finding was

observed in a recent prospective observational study performed

between November 2011 and October 2013 (78). This study analyzed the incidence of

healthcare-associated urinary tract infections in patients admitted

to the urology ward of University Hospital 12 de Octubre in Spain

with an indwelling urinary catheter. The incidence of CA-UTI in

males vs. females was 8.22 vs. 8.46% without significant difference

(78). The study also analyzed the

four most frequently cultured bacteria species in CA-UTI (E.

coli, Enterococcus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas) and identified no

significant difference between genders. The diversities in the

results of these studies results may be affected by other

unidentified factors, including urinary catheter management or

personal hygiene influence.

In accordance with PUBS being associated with

infectious pathology of the urinary tract, the mean WBC count of

all reviewed cases was elevated to 12,242/µl. Furthermore, WBC

count significantly increased with time between 2001–2010 and

2011–2016.

There were 11.8% of PUBS cases presenting with fever

and 8.6% of cases presenting with hypotension without significant

difference between the decades. A total of 58.3% of subjects lived

in long-term care units, and 19.2% had a history of diabetes. Urine

pH value was the most stationary variable in each decade, varying

between 8.0 and 8.1, which is compatible with the recognized

conclusion from studies on PUBS: That PUBS more readily occurs in

alkaline over acidic urine (2–4).

A small cohort study of Taiwanese patients

demonstrated chronic kidney disease (CKD) to be a risk factor for

PUBS (79). The serum and urine

levels of indoxyl sulfate are increased markedly in patients with

chronic kidney disease or in those undergoing dialysis due to

impaired renal clearance (80). In

the present study, 18.8% of PUBS cases had a history of uremia.

Previous studies have also indicated comorbid conditions including

diabetes mellitus, dementia and iron deficiency anemia are

independent risk factors for ABU and UTI (80,81).

It has previously been concluded there is an

association of CA-UTI with increased mortality rate and prolonged

length of stay in acute care facilities (82). Furthermore, for PUBS involving

Fournier's gangrene in immunosuppressed patients, the morbidity and

mortality rates were increased (30).

Nevertheless, in uremic patients with PUBS, the elimination of

indoxyl sulfate during dialysis is limited as it is bound to

albumin, leading to exponential increase in serum indoxyl sulfate

concentration. When treating patients with CKD and PUBS, clinicians

should consider the elevated serum and urinary concentration of

indoxyl sulfate due to its potential role in the progression of

CKD, as well as its contribution to cardiovascular events (57).

Constipation is considered to be a predisposing

factor in PUBS due to the increased time it elicits for bacterial

deamination. In the present study, constipation rate significantly

decreased after 2001, though this may have been an artifact based

on the relatively small number of cases reported in the decade of

1991–2000.

Overall mortality rate was 6.8%, thus indicating

that PUBS is not always a benign process. However, mortality rate

declined with time over the three decades, concordant with the

introduction of EGDT for severe sepsis in 2001 (83). Therefore, this progress may be

attributed to the new recommendation of EGDT, which may achieve

aggressive correction of septic shock when combined with early

appropriate antibiotic administration. Nonetheless, the mortality

rate of patients with severe sepsis declined following the

implementation of EGDT (84–87). A recent meta-analysis study also

concluded that important factors contributing to improved outcome

are time-to-first antibiotic administration and appropriate

antibiotic use (88).

In conclusion, the ratio of males: females with PUBS

increased over recent decades. Therefore, the urine color in

catheterized patients should be monitored not only in female but

also male patients. PUBS may not always be a benign process, and

emphasis is required on early examination and aggressive antibiotic

administration. Although WBC count was elevated over the recent

decades, the morality rate was lowest in the most recent five years

and decreased by decade; the overall mortality rate was 6.8%, and

lowered to 4.3% in the last five years.

This was a case-controlled study that searched

relevant articles in the PubMed database. A limitation of this may

have been the exclusion of cases based on inadequate information,

leading to bias and introducing confounding factors. Furthermore,

the relatively small number of PUBS studies in each decade may have

limited the accuracy of statistical analyses. There may also be

cases of PUBS unreported in the PubMed database which were

unaccounted for.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed data sets generated during the study

are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

The final version of the manuscript has been read

and approved by all authors. YHW collected the data and wrote the

draft. SYJ planned and revised the study and is the primary

correspondent.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Barlow GB and Dickson JAS: PURPLE URINE

BAGS. Lancet. 311:220–221. 1978. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Dealler SF, Hawkey PM and Millar MR:

Enzymatic degradation of urinary indoxyl sulfate by Providencia

stuartii and Klebsiella pneumoniae causes the purple urine bag

syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 26:2152–2156. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Su FH, Chung SY, Chen MH, Sheng ML, Chen

CH, Chen YJ, Chang WC, Wang LY and Sung KY: Case analysis of purple

urine-bag syndrome at a long-term care service in a community

hospital. Chang Gung Med J. 28:636–642. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Umeki S: Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS)

associated with strong alkaline urine. Kansenshogaku Zasshi.

67:1172–1177. 1993.(In Japanese). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nobukuni K, Kawahara S, Nagare H and

Fujita Y: Study on purple pigmentation in five cases with purple

urine bag syndrome. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 69:1269–1271. 1995.(In

Japanese). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Al-Jubouri MA and Vardhan MS: A case of

purple urine bag syndrome associated with Providencia rettgeri. J

Clin Pathol. 54:4122001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ihama Y and Hokama A: Purple urine bag

syndrome. Urology. 60:9102002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rohaut B, Bachmeyer C, Lecomte I, Ravet N

and Grateau G: A urine bag turns purple. Rev Med Interne.

26:666–667. 2005.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vallejo-Manzur F, Mireles-Cabodevila E and

Varon J: Purple urine bag syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 23:521–524.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang IK, Ho DR, Chang HY, Lin CL and

Chuang FR: Purple urine bag syndrome in a hemodialysis patient.

Intern Med. 44:859–861. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Achtergael W, Michielsen D, Gorus FK and

Gerlo E: Indoxyl sulphate and the purple urine bag syndrome: A case

report. Acta Clin Belg. 61:38–41. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Beunk J, Lambert M and Mets T: The purple

urine bag syndrome. Age Ageing. 35:5422006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tang MW: Purple urine bag syndrome in

geriatric patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 54:560–561. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bar-Or D, Rael LT, Bar-Or R, Craun ML,

Statz J and Garrett RE: Mass spectrometry analysis of urine and

catheter of a patient with purple urinary bag syndrome. Clin Chim

Acta. 378:216–218. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gautam G, Kothari A, Kumar R and Dogra PN:

Purple urine bag syndrome: A rare clinical entity in patients with

long term indwelling catheters. Int Urol Nephrol. 39:155–156. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Harun NS, Nainar SK and Chong VH: Purple

urine bag syndrome: A rare and interesting phenomenon. South Med J.

100:1048–1050. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lazimy Y, Delotte J, Machiavello JC,

Lallement M, Imbenotte M and Bongain A: Purple urine bag syndrome:

A case report. Prog Urol. 17:864–865. 2007.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nair UV, Chattopadhyay I, Giles M, Curtis

G and Mannion PT: Purple urine bag syndrome in an octogenarian

male. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 68:1052007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pillai RN, Clavijo J, Narayanan M, et al:

An association of purple urine bag syndrome with intussusception.

Urology. 70:812 e1–2. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Su YJ, Lai YC and Chang WH: Purple urine

bag syndrome in a dead-on-arrival patient: case report and articles

reviews. Am J Emerg Med. 25:861 e5–6. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ting IW, Wang R, Wu VC, Hsueh PR and Hung

KY: Purple urine bag syndrome in a hemodialysis patient. Kidney

Int. 71:9562007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chiang HC, Huang MS and Cheng CC: An

experience providing home care to a victim of cerebral vascular

accident and purple urine bag syndrome. Hu Li Za Zhi. 55:98–104.

2008.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chung SD, Liao CH and Sun HD: Purple urine

bag syndrome with acidic urine. Int J Infect Dis. 12:526–527. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lin CH, Huang HT, Chien CC, Tzeng DS and

Lung FW: Purple urine bag syndrome in nursing homes: Ten elderly

case reports and a literature review. Clin Interv Aging. 3:729–734.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Muneoka K, Igawa M, Kurihara N, Kida J,

Mikami T, Ishihara I, Uchida J, Shioya K, Uchida S and Hirasawa H:

Biochemical and bacteriological investigation of six cases of

purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) in a geriatric ward for dementia.

Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 45:511–519. 2008.(In Japanese).

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shiao CC, Weng CY, Chuang JC, Huang MS and

Chen ZY: Purple urine bag syndrome: A community-based study and

literature review. Nephrology (Carlton). 13:554–559. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Vidarsdottir H, Palsson R and Gudbjartsson

T: Case of the month; purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS).

Laeknabladid. 94:383–385. 2008.(In Icelandic). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Al-Sardar H and Haroon D: Purple urinary

bag syndrome. Am J Med. 122:e1–e2. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pillai BP, Chong VH and Yong AM: Purple

urine bag syndrome. Singapore Med J. 50:e193–e194. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tasi YM, Huang MS, Yang CJ, Yeh SM and Liu

CC: Purple urine bag syndrome, not always a benign process. Am J

Emerg Med. 27:895–897. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

van Iersel M and Mattijssen V: Purple

urine bag syndrome. Neth J Med. 67:340–341. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu HH, Yang WC and Lin CC: Purple urine

bag syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 337:3682009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ferrara F, D'Angelo G and Costantino G:

Monolateral purple urine bag syndrome in bilateral nephrostomy.

Postgrad Med J. 86:6272010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hirzallah MI and D'Souza DL: Purple urine

bag syndrome in a patient with a nephrostomy tube. N Z Med J.

123:68–70. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Siu G and Watanabe T: Purple urine bag

syndrome in rehabilitation. PM R. 2:303–306. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Su HK, Lee FN, Chen BA and Chen CC: Purple

urine bag syndrome. Emerg Med J. 27:7142010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kang KH, Jeong KH, Baik SK, Huh WY, Lee

TW, Ihm CG, Lee SH and Moon JY: Purple urine bag syndrome: Case

report and literature review. Clin Nephrol. 75:557–559. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Keenan CR and Thompson GR III: Purple

urine bag syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 26:15062011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Khan F, Chaudhry MA, Qureshi N and Cowley

B: Purple urine bag syndrome: An alarming hue? A brief review of

the literature. Int J Nephrol. 2011:4192132011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Peters P, Merlo J, Beech N, Giles C, Boon

B, Parker B, Dancer C, Munckhof W and Teng HS: The purple urine bag

syndrome: A visually striking side effect of a highly alkaline

urinary tract infection. Can Urol Assoc J. 5:233–234. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zeier MG, Lee KG and Tan CS: An elderly

nursing home resident with unusual urine bag discoloration. NDT

Plus. 4:445–446. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bocrie OJ, Bouchoir E, Camus A, Popitean L

and Manckoundia P: Purple urine bag syndrome in an elderly subject.

Braz J Infect Dis. 16:597–598. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cantaloube L, Lebaudy C, Hermabessière S

and Rolland Y: Pastel in the urine bag. Geriatr Psychol

Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 10:5–8. 2012.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Domínguez Alegría AR, Vélez Díaz-Pallares

M, Moreno Cobo MA, Arrieta Blanco F and Bermejo Vicedo T: Purple

urine bag syndrome in elderly woman with nutritional supplements.

Nutr Hosp. 27:2130–2132. 2012.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Meekins PE, Ramsay AC and Ramsay MP:

Purple urine bag syndrome. West J Emerg Med. 13:499–500. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Al Montasir A and Al Mustaque A: Purple

urine bag syndrome. J Family Med Prim Care. 2:104–105. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Bhattarai M, Bin Mukhtar H, Davis TW,

Silodia A and Nepal H: Purple urine bag syndrome may not be benign:

A case report and brief review of the literature. Case Rep Infect

Dis. 2013:8638532013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Canavese C, Airoldi A, Quaglia M, Barbè

MC, Brustia M, Vidali M, Bagnati M, Andreone S, Corrà T, Sciarrabba

C, et al: Recognizing purple bag syndrome at first look. J Nephrol.

26:465–469. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Duff ML: Case report: Purple urine bag

syndrome. J Emerg Med. 44:e335–e336. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Iglesias Barreira R, Albiñana Pérez MS,

Rodríguez Penín I and Bilbao Salcedo J: Purple urine bag syndrome

in two institutionalised patients. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol.

48:45–47. 2013.(In Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Mohamad Z and Chong VH: Purple urine bag:

Think of urinary tract infection. Am J Emerg Med. 31:265 e5–6.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Ungprasert P, Ratanapo S, Cheungpasitporn

W, Kue-A-Pai P and Bischof EF Jr: Purple urine bag syndrome. Clin

Kidney J. 6:3442013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wolff N, Indaburu I, Muller F and Mariescu

Depaire N: Purple urine bag syndrom. Prog Urol. 23:538–539.

2013.(In French). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Yaqub S, Mohkum S and Mukhtar KN: Purple

urine bag syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Indian

J Nephrol. 23:140–142. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Agapakis D, Massa E, Hantzis I, Paschoni E

and Satsoglou E: Purple Urine Bag Syndrome: A case report of an

alarming phenomenon. Hippokratia. 18:92–94. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Chassin-Trubert CAM: Purple urine bag

syndrome: Report of one case. Rev Med Chil. 142:1482–1484. 2014.(In

Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Delgado G, Martínez-Reséndez M and

Camacho-Ortiz A: Purple urine bag syndrome in end-stage chronic

kidney disease. J Bras Nefrol. 36:542–544. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hloch O, Gladišová D and Horáčková M:

Purple urine bag syndrome - rare but substantial symptom of urinary

infection. Vnitr Lek. 60:512–513. 2014.(In Czech). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Restuccia MR and Blasi M: A PUBS Case in a

Palliative Care Unit Experience. Case Rep Oncol Med.

2014:1697822014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sheehan M: Monolateral purple urine bag

syndrome in a patient with bilateral nephrostomy tubes. Urol Nurs.

34:135–138. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Abubacker NR, Jayaraman SMRK, Sivanesan MK

and Mathew R: Purple Urine Bag Syndrome. J Clin Diagn Res.

9:OD01–OD02. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Alex R, Manjunath K, Srinivasan R and Basu

G: Purple urine bag syndrome: Time for awareness. J Family Med Prim

Care. 4:130–131. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Karim A, Abed F and Bachuwa G: A

unilateral purple urine bag syndrome in a patient with bilateral

nephrostomy tubes. BMJ Case Rep. 2015.https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-212913

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Kenzaka T: Purple urine bag syndrome in a

patient with a urethral balloon catheter and a history of ileal

conduit urinary diversion. Korean J Intern Med. 30:4202015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Mohamed Faisal AH, Shathiskumar G and

Nurul Izah A: Purple urine bag syndrome: Case report from a nursing

home resident with a false alarm of urosepsis. Med J Malaysia.

70:265–266. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Mondragón-Cardona A, Jiménez-Canizales CE,

Alzate-Carvajal V, Bastidas-Rivera F and Sepúlveda-Arias JC: Purple

urine bag syndrome in an elderly patient from Colombia. J Infect

Dev Ctries. 9:792–795. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Neweling F and Janssens U: Lila Urin bei

einem Patienten mit beidseitiger Nephrostomie. Med Klin Intensivmed

Notf Med. 111:731–733. 2016.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Redwood R, Medlin J and Pulia M: Elderly

Man With Dark Urine. Purple urine bag syndrome. Ann Emerg Med.

66:436, 4402015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Van Keer J, Detroyer D and Bammens B:

Purple Urine Bag Syndrome in Two Elderly Men with Urinary Tract

Infection. Case Rep Nephrol. 2015:7469812015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Demelo-Rodríguez P, Galán-Carrillo I and

Del Toro-Cervera J: Purple urine bag syndrome. Eur J Intern Med.

35:e3–e4. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Faridi MS, Rahman MJ, Mibang N, Shantajit

N and Somarendra K: Purple Urine Bag Syndrome- An Alarming

Situation. J Clin Diagn Res. 10:PD05–PD06. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Richardson-May J: Single case of purple

urine bag syndrome in an elderly woman with stroke. BMJ Case Rep.

Aug 3–2016.https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215465

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Sriramnaveen P, Reddy YS, Sridhar A,

Kishore CK, Manjusha Y and Sivakumar V: Purple urine bag syndrome

in chronic kidney disease. Indian J Nephrol. 26:67–68. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Tul Llah S, Khan S, Dave A, Morrison AJ,

Jain S and Hermanns D: A Case of Purple Urine Bag Syndrome in a

Spastic Partial Quadriplegic Male. Cureus. 8:e5522016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Mantani N, Ochiai H, Imanishi N, Kogure T,

Terasawa K and Tamura J: A case-control study of purple urine bag

syndrome in geriatric wards. J Infect Chemother. 9:53–57. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Vincitorio D, Barbadoro P, Pennacchietti

L, Pellegrini I, David S, Ponzio E and Prospero E: Risk factors for

catheter-associated urinary tract infection in Italian elderly. Am

J Infect Control. 42:898–901. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Eckenrode S, Bakullari A, Metersky ML,

Wang Y, Pandolfi MM, Galusha D, Jaser L and Eldridge N: The

association between age, sex, and hospital-acquired infection

rates: Results from the 2009–2011 National Medicare Patient Safety

Monitoring System. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 35 Suppl 3:S3–S9.

2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Jiménez-Alcaide E, Medina-Polo J,

García-González L, Arrébola-Pajares A, Guerrero-Ramos F,

Pérez-Cadavid S, Sopeña-Sutil R, Benítez-Sala R, Alonso-Isa M,

Lara-Isla A, et al: Healthcare-associated urinary tract infections

in patients with a urinary catheter: Risk factors, microbiological

characteristics and patterns of antibiotic resistance. Arch Esp

Urol. 68:541–550. 2015.(In Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Yang CJ, Lu PL, Chen TC, Tasi YM, Lien CT,

Chong IW and Huang MS: Chronic kidney disease is a potential risk

factor for the development of purple urine bag syndrome. J Am

Geriatr Soc. 57:1937–1938. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Jackson SL, Boyko EJ, Scholes D, Abraham

L, Gupta K and Fihn SD: Predictors of urinary tract infection after

menopause: A prospective study. Am J Med. 117:903–911. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Nicolle LE: Urinary tract infections in

the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 25:423–436. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Chant C, Smith OM, Marshall JC and

Friedrich JO: Relationship of catheter-associated urinary tract

infection to mortality and length of stay in critically ill

patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational

studies. Crit Care Med. 39:1167–1173. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J,

Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E and Tomlanovich M; Early

Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group, : Early goal-directed

therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl

J Med. 345:1368–1377. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Liu B, Ding X and Yang J: Effect of early

goal directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and/or

septic shock. Curr Med Res Opin. 32:1773–1782. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Xing L, Tong L, Jun L, Xinjing G and Lei

X: Effect of early goal-directed therapy on mortality in patients

with severe sepsis or septic shock: A Meta analysis. Zhonghua Wei

Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 27:735–738. 2015.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Cai G, Tong H, Hao X, Hu C, Yan M, Chen J

and Yan J: The effects of early goal-directed therapy on mortality

rate in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: A systematic

literature review and Meta-analysis. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu

Yi Xue. 27:439–442. 2015.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Puskarich MA, Marchick MR, Kline JA,

Steuerwald MT and Jones AE: One year mortality of patients treated

with an emergency department based early goal directed therapy

protocol for severe sepsis and septic shock: A before and after

study. Crit Care. 13:R1672009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Kalil AC and Kellum JA: Is Early

Goal-Directed Therapy Harmful to Patients With Sepsis and High

Disease Severity? Crit Care Med. 45:1265–1267. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|