Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) include hydrogen

peroxide, nitric oxide, superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals and

peroxynitrite. A growing body of evidence suggests that ROS within

cells act as second messengers in the regulation of many important

cellular events, including transcription factor activation, gene

expression and cellular proliferation, differentiation and

senescence (1,2). An excessive production of ROS

frequently leads to serious damage in cells, while mild increases

in ROS can induce cellular senescence (3,4).

ROS can therefore function as antitumorigenic agents (5–7).

Many anticancer therapies, such as the chemotherapeutic agent

doxorubicin, etoposide and cisplatin, in addition to radiotherapy

and photodynamic therapy, can lead to the generation of superoxide

and oxygen radicals within carcinoma cells (8,9).

In this sense, the modulation of oxidative stress could be a target

of anticancer therapies.

A variety of proteins function as ROS scavengers,

such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase,

thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), ascorbate, glutathione. Among them,

TrxR has been suggested as a new target for anticancer drug

development because TrxR is overexpressed in colon, pancreas, lung

and other cancers (10–12) and knockdown of TrxR could

dramatically reduce tumor growth and metastasis in a lung carcinoma

mouse model (13). Developing the

novel TrxR targeting compound is promising in the treatment of

cancer (14).

Oridonin is an ent-kaurane diterpenoid derived from

Rabdosia rubescens (15).

Studies have shown that oridonin induces apoptosis in a variety of

cancer cells including cells from prostate cancer, breast cancer,

non-small cell lung cancer, acute leukemia, glioblastoma multiforme

and melanoma (16–19). In addition, oridonin can also

inhibit cell cycle progression and enhance phagocytosis of

apoptotic cells by macrophages (20). However, the mechanisms underlying

the antitumor activity of oridonin are not fully understood.

Interestingly, exposure of acute promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells

to oridonin resulted in a significant increase in ROS generation

while the ROS scavenger, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), completely

protected NB4 cells from oridonin-induced apoptosis (16). These findings indicate that ROS

signaling is involved in oridonin-induced apoptosis. Recently, we

demonstrated that oridonin could induce potent growth inhibition,

apoptosis, and senescence of colorectal cancer cells in

vitro and in vivo (21). However, the exact mechanism of

this process remains largely unknown.

In the present study, the role of ROS and

thioredoxin reductase in oridonin-induced cell death and senescence

in human colorectal cancer (SW1116) cells were investigated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The colorectal cancer cell line SW1116 was purchased

from the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences. The cells

were maintained in a humidified room air containing 5%

CO2 at 37°C and cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco-BRL)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL). Cells in the logarithmic phase

of growth were used in all experiments.

Reagents

Oridonin (98% purity) provided by Dr Tang Qingjiu

(Shanghai Academy of Agricultural Sciences) was dissolved in DMSO

(Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a stock concentration of 10 mg/ml and

stored at −20°C. The cell-permeable ROS scavenger NAC was obtained

from Sigma and dissolved in sterile H2O to a stock

concentration of 100 mM. Catalase was obtained from Sigma and

dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at 4,733 U/ml. All

stock solutions were wrapped in foil and maintained at 4°C or

−20°C.

Detection and measurement of

intracellular hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion

concentrations

Two oxidation-sensitive fluorescent probe dyes,

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA, Invitrogen,

Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and dihydroethidium (DHE, Invitrogen

Molecular Probes), were used to measure the intracellular hydrogen

peroxide and superoxide anion concentrations, respectively. DCF-DA

is deacetylated intracellularly by nonspecific esterases and is

further oxidized by cellular peroxides to the fluorescent compound

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein. DHE is a fluorogenic probe that detects

superoxide anion radicals with high selectivity. DHE is

cell-permeable and reacts with superoxide anions to form ethidium,

which in turn intercalates deoxyribonucleic acid and exhibits a red

fluorescence. Briefly, cells were treated with oridonin in the

presence or absence of NAC or catalase for the indicated time

periods. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells

were incubated with 20 μM DCF-DA or 5 μM DHE at 37°C for 30 min

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The fluorescence

signals were detected by a FACStar flow cytometer (Beckman

Coulter). For each sample, 5,000 or 10,000 events were collected.

Hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion levels were expressed in

terms of mean fluorescence intensity.

Detection of intracellular glutathione

(GSH)

Cellular GSH levels were analyzed using

5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (CMFDA, Invitrogen, Molecular

Probes). Cytoplasmic esterases convert nonfluorescent CMFDA to

fluorescent 5-chloromethylfluorescein, which can then react with

the glutathione. CMFDA is a useful membrane-permeable dye for

determining levels of intracellular glutathione (22–25). Briefly, cells were treated with

oridonin in the presence or absence of ROS scavengers, or catalase

for the indicated time periods. After washing with PBS, the cells

were incubated with 5 μM CMFDA at 37°C for 30 min according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. CMF fluorescence was detected by the

FACStar flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). For each sample, 5,000 or

10,000 events were collected.

Annexin V/PI staining

Apoptosis was determined using Annexin V-fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC) staining and PI labeling. Annexin V can

identify the externalization of phosphatidylserine during apoptotic

progression and therefore can detect cells in early apoptosis.

Briefly, cells were treated with oridonin in the presence or

absence of NAC or catalase for the indicated time periods. After

washing twice with cold PBS, cells were resuspended in 500 μl of

binding buffer [10 mM HEPES/NaOH (pH 7.4), 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM

CaCl2] at a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml.

Next, 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and 10 μl

of 20 μg/ml PI were added to these cells, which were analyzed with

a FACStar flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Viable cells were

negative for both PI and Annexin V, apoptotic cells were positive

for Annexin V and negative for PI, and late apoptotic dead cells

displayed both high Annexin V and PI labeling. Non-viable cells

that had undergone necrosis were positive for PI and negative for

Annexin V.

Cell senescence assay

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity was

determined with a senescence detection kit (Biovision, Mountain

View, CA) using fixed cells (26). The development of a blue color in

the cytoplasm was detected and photographed using a Nikon (Nikon

Instruments Inc., Lewisville, TX) inverted microscope equipped with

a color CCD camera. Four pictures were taken of each well.

β-galactosidase-stained cells and unstained cells were counted and

used to calculate a final average ratio of the number of stained to

unstained cells in each well.

Western blot analysis

Cells were incubated with oridonin and/or NAC for

the indicated time periods. Cells were then washed in PBS and

suspended in five volumes of lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9),

20% glycerol, 200 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, 1%

protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)]. The lysates were then

collected and stored at −20°C. Protein concentrations in the

supernatants were determined by the Bradford method. Supernatant

samples containing 20 μg of total protein were resolved on 10–15%

SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto Immobilon-P PVDF membranes

(Millipore, MA) by electroblotting; membranes were then probed with

anti-PARP, p16, c-Myc and p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.,

Santa Cruz, CA) primary antibodies and subsequently with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The

membrane blots were developed using the ECL kit (Amersham,

Arlington Heights, IL).

Determination of TrxR activity by the

dithionitrobenzene reduction assay

All experiments were performed in 96-well plates.

Recombinant active rat TrxR (0.05 units) was incubated with various

concentrations of oridonin for 60 min. TrxR activity was assayed by

the dithionitrobenzene method in a solution containing 50 mM

Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 μM NADPH, 5 mM DTNB, and 1 mM EDTA. The

absorbance at 412 nm was measured with a Synergy H4 Hybrid

Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). A blank reading without

TrxR was subtracted from every sample. TrxR enzyme activity was

calculated as a percentage of the activity of the DMSO

vehicle-treated sample.

Determination of TrxR activity in cell

lysates

The activity of TrxR in cell lysates was measured

using the TrxR assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) according

to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were collected

by scraping and were homogenized on ice in cold buffer (50 mM

potassium phosphate and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). The protein

concentration in the supernatant of the lysate was determined using

the Bradford method. Protein samples, NADPH, and DTNB were added to

the assay buffer in 96-well plates and gently mixed. The absorbance

at 412 nm was measured with a Synergy H4 Hybrid Microplate Reader.

A blank reading without protein was subtracted from every sample.

TrxR enzyme activity was calculated as a percentage of the activity

of the DMSO vehicle-treated control sample.

Statistical analysis

The Student’s t-test was used to evaluate the

differences between two different groups. A P-value <0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

Oridonin increases hydrogen peroxide and

decreases superoxide anion and glutathione levels in SW1116

cells

First, the production of intracellular hydrogen

peroxide was assessed in oridonin-treated SW1116 cells using the

DCF-DA fluorescence dye. As shown in Fig. 1A, oridonin increased the

intracellular hydrogen peroxide level in a dose-dependent manner.

Treatment with oridonin at 6.25 μM for 2 h increased the

intracellular hydrogen peroxide levels, compared with those in the

untreated control cells. The intracellular superoxide anion level

in oridonin-treated SW1116 cells was assessed using the DHE

fluorescence dye. Red fluorescence derived from DHE, which reflects

superoxide anion accumulation, decreased significantly in SW1116

cells treated with 50 and 100 μM oridonin, compared with the

untreated control cells (Fig.

1B).

As an important component of the antioxidant system,

cellular GSH has been shown to be crucial for the regulation of

cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, apoptosis and

senescence. We therefore analyzed the changes of GSH level in

oridonin-treated SW1116 cells by using the CMF fluorescence probe.

Oridonin at 50 or 100 μM significantly decreased the level of

intracellular GSH content at 2 h (Fig. 1C), indicating the depletion of

intracellular GSH content of SW1116 cells. The decrease of CMF

fluorescence was observed within 120 min at the exposure to

oridonin (50 and 100 μM) (Fig.

1C). However, at a lower concentration (6.25–25 μM), a slight

increase of the CMF fluorescence was detected at 2 h.

The ROS scavenger NAC protects SW1116

cells from oridonin-induced apoptosis or senescence

To determine the role of ROS production in

oridonin-induced apoptosis and senescence, SW1116 cells were

treated with oridonin in the presence or absence of NAC, a well

known ROS scavenger, for 2 h. As expected, NAC fully reversed the

oridonin-induced increase in hydrogen peroxide as well as the

decrease in superoxide anion and GSH levels (Fig. 2A–C). Next, effects of NAC on

oridonin-induced cell death and senescence in SW1116 cells were

also examined. As shown in Fig. 2D

and E, co-treatment with NAC and oridonin completely protected

the cells from oridonin-induced cell death and senescence.

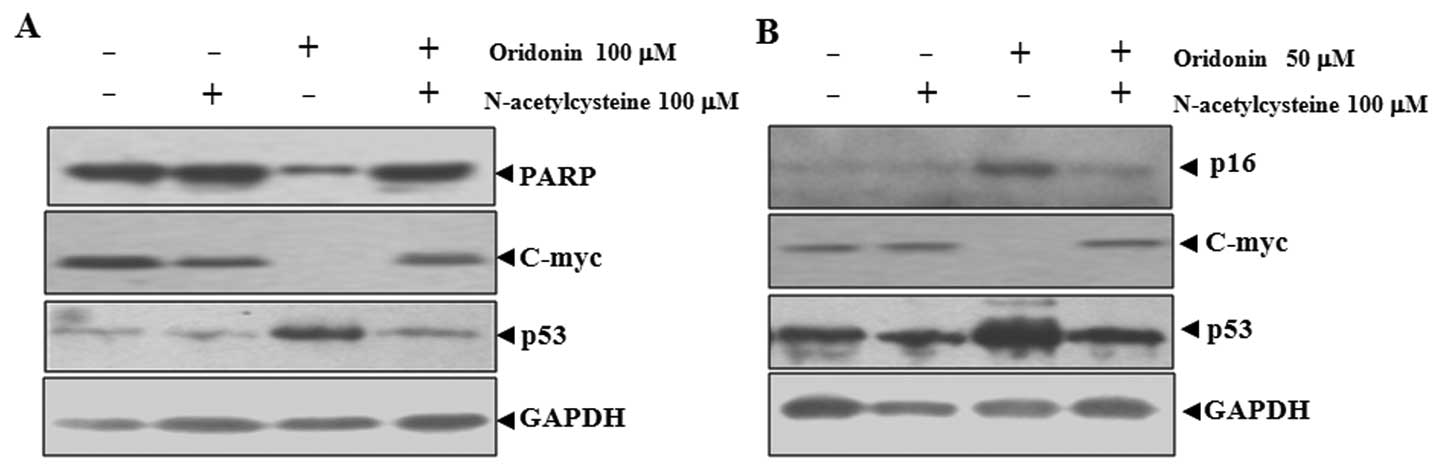

NAC abrogates oridonin-induced changes in

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), p16, p53 and c-Myc in SW1116

cells

Oridonin-induced apoptosis and senescence were

related to the upregulation of p53 and p16 and downregulation of

c-Myc (21). Because NAC can

inhibit oridonin-induced apoptosis and senescence, the effect of

NAC on the expression of these proteins was examined. As shown in

Fig. 3A, the application of

oridonin at 100 μM mainly led to apoptosis in SW1116 cells, as

indicated by the degradation of PARP, which is a major substrate

for caspases and a marker for apoptosis (27). Co-treatment with NAC inhibited the

degradation of PARP. At 50 μM, oridonin mainly induced senescence

in SW1116 cells, as reflected by the induction of p16, a hallmark

of both replicative and accelerated senescence (28). In this case, co-treatment with NAC

inhibited the induction of p16 (Fig.

3B).

The inactivation of c-Myc and the activation of p53

are important for both apoptosis and senescence (29–32). NAC co-treatment abrogated

oridonin-induced downregualtion of c-Myc and upregulation of p53 in

parallel with the inhibition of apoptosis and senescence (Fig. 3). These results indicated that

c-Myc and p53 are involved in oridonin-induced senescence and

apoptosis.

Effects of catalase on ROS production,

apoptosis and senescence in oridonin-treated SW1116 cells

To further determine the role of hydrogen peroxide

in oridonin-induced apoptosis and senescence, SW1116 cells were

treated with oridonin in the presence or absence of catalase (30

U/ml), a hydrogen peroxide-scavenging enzyme (33). Catalase partially reversed an

oridonin-induced increase in hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 4A) but not the decrease of

superoxide anion and GSH (Fig. 4B and

C). Interestingly, catalase significantly decreased the

percentage of Annexin V-positive cells (Fig. 4D) but not the

senescence-associated β-galactosidase-positive cells induced by

oridonin (Fig. 4E).

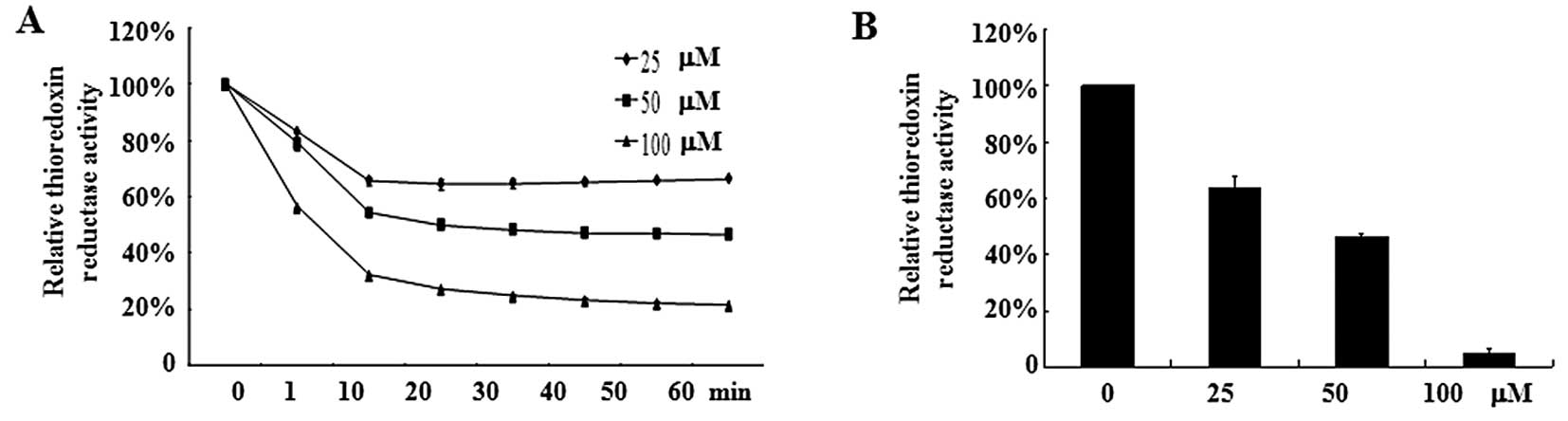

Oridonin inhibits TrxR activity

TrxR, an oxidoreductase that reduces oxidized

proteins, represents an important valid target for cancer therapy.

Because TrxR is easily targeted by electrophilic compounds and

oridonin is a Michael acceptor with electrophilic propensity, we

assumed that oridonin may directly inhibit TrxR activity, which

causes an increase of hydrogen peroxide. As shown in Fig. 5A, oridonin caused a dose-dependent

reduction of TrxR activity in vitro. Incubation of TrxR with

100 μM oridonin led to an 80% decrease in TrxR activity compared

with DMSO treatment. In line with this result, SW1116 cells treated

with oridonin at 50 or 100 μM for 2 h exhibited a marked decrease

in TrxR activity (Fig. 5B). These

results indicate that TrxR is one of the targets for oridonin.

Discussion

We previously reported that oridonin induces potent

growth inhibition, apoptosis, and senescence of colorectal cancer

cells in vitro and in vivo (21). However, the underlying mechanism

is largely unknown. In this study, we demonstrated that the

antitumor activity of oridonin was attributed to its ROS increasing

activity. Furthermore, TrxR inhibition is involved in this

process.

ROS serve many cellular functions including actins

as growth stimulants, second messengers, aging accelerants, cell

death inducers and antibacterial agents. Based on our previous

results and those of others (16,34), we hypothesized that oridonin may

induce apoptosis and senescence in colon cancer cells via

increasing ROS. Although it is currently not possible to precisely

quantify the amount of subcellular ROS, tools to detect several

kinds of ROS in the cells are available. With these chemical

probes, we found that exposure to oridonin led to the increase of

hydrogen peroxide and decrease of superoxide anions and GSH in

SW116 cells and that the effects of oridonin on ROS level were

dose-dependent. In the cellular environment, hydrogen peroxide can

be derived from superoxide anions; this derivation can either occur

spontaneously or can be catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (35). Whether oridonin could enhance the

conversion of superoxide anions to hydrogen peroxide or inhibit the

production of superoxide anions is currently unknown.

Many studies have demonstrated that hydrogen

peroxide plays an important role in chemotherapy-induced apoptosis

and senescence in cells (6–9).

At low or mild concentrations, ROS seem to protect the cells or

induce cell senescence, while at high concentration, ROS can

initiate cell death by damaging many biological molecules. To

reveal the role of hydrogen peroxide in oridonin-induced apoptosis,

NAC, an ROS scavenger, were used in combination with oridonin. NAC

completely abrogated the oridonin-induced increases of hydrogen

peroxide levels and decreases of superoxide anion levels.

Accordingly, oridonin induced apoptosis and senescence and the

relevant changes of p53, p16 and c-Myc were also abrogated. These

data indicate that hydrogen peroxide plays a key role in

oridonin-induced apoptosis and senescence. Interestingly, when the

levels of hydrogen peroxide were partially decreased by catalase,

only the apoptosis but not the senescence was significantly

reversed, indicating that the concentration of hydrogen peroxide

determined the cell fate. These data suggest that hydrogen peroxide

may play a major role in oridonin-induced apoptosis and senescence,

although we cannot rule out tht other ROS, such as nitric oxide, or

hydroxyl radicals may also be involved.

The mammalian thioredoxin system, which consists of

NADPH, thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase, plays an important

role in protecting cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis

(36). As overexpression of TrxR

has been reported in several human cancers and is associated with

decreased survival and resistance to chemotherapy, TrxR has been

proposed as a target for anticancer drug development. Considering

the extensive involvement of TrxR in the redox regulations and its

close link with cancer and that it is easily attacked by

electrophilic compound, we investigated the effect of oridonin on

TrxR activity. Interestingly, oridonin dose-dependently inhibited

the activity of TrxR in vitro and in cells. The trend was

correlated to that of oridonin-induced hydrogen peroxide increase.

Thus, oridonin may induce the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide by

targeting TrxR.

In summary, we show here that hydrogen peroxide

plays an important role in oridonin-induced apoptosis and

senescence in colon cancer cells. We also provided evidence for the

first time that oridonin could inhibit TrxR activity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Basic

Research Program of China (no. 2010CB912104), the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (nos. 81070433, 91013008 and 81172322),

the Science and Technology Committee of Baoshan District (08-E-13),

and the Number 3 People’s Hospital affiliated with the Shanghai

Jiao-Tong University School of Medicine (syz07-04).

References

|

1

|

C GonzalezG Sanz-AlfayateMT AgapitoA

Gomez-NinoA RocherA ObesoSignificance of ROS in oxygen sensing in

cell systems with sensitivity to physiological hypoxiaRespir

Physiol

Neurobiol1321741200210.1016/S1569-9048(02)00047-212126693

|

|

2

|

CP BaranMM ZeiglerS TridandapaniCB

MarshThe role of ROS and RNS in regulating life and death of blood

monocytesCurr Pharm

Des10855866200410.2174/138161204345286615032689

|

|

3

|

J YamadaS YoshimuraH YamakawaCell

permeable ROS scavengers, Tiron and Tempol, rescue PC12 cell death

caused by pyrogallol or hypoxia/reoxygenationNeurosci

Res4518200310.1016/S0168-0102(02)00196-712507718

|

|

4

|

A TakahashiN OhtaniK YamakoshiMitogenic

signalling and the p16INK4a-Rb pathway cooperate to enforce

irreversible cellular senescenceNat Cell

Biol812911297200610.1038/ncb149117028578

|

|

5

|

S MenaA OrtegaJM EstrelaOxidative stress

in environmental-induced carcinogenesisMutat

Res6743644200910.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.01718977455

|

|

6

|

AT ShawMM WinslowM MagendantzSelective

killing of K-ras mutant cancer cells by small molecule inducers of

oxidative stressProc Natl Acad Sci

USA10887738778201110.1073/pnas.110594110821555567

|

|

7

|

L RajT IdeAU GurkarSelective killing of

cancer cells by a small molecule targeting the stress response to

ROSNature475231234201110.1038/nature1016721753854

|

|

8

|

RH EngelAM EvensOxidative stress and

apoptosis: a new treatment paradigm in cancerFront

Biosci11300312200610.2741/179816146732

|

|

9

|

P StorzReactive oxygen species in tumor

progressionFront Biosci1018811896200510.2741/166715769673

|

|

10

|

Y SunB RigasThe thioredoxin system

mediates redox-induced cell death in human colon cancer cells:

implications for the mechanism of action of anticancer agentsCancer

Res6882698277200810.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-201018922898

|

|

11

|

H HanDJ BearssLW BrowneR CalaluceRB

NagleDD Von HoffIdentification of differentially expressed genes in

pancreatic cancer cells using cDNA microarrayCancer

Res6228902896200212019169

|

|

12

|

Y SoiniK KahlosU NapankangasWidespread

expression of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase in non-small

cell lung carcinomaClin Cancer Res717501757200111410516

|

|

13

|

MH YooXM XuBA CarlsonVN GladyshevDL

HatfieldThioredoxin reductase 1 deficiency reverses tumor phenotype

and tumorigenicity of lung carcinoma cellsJ Biol

Chem2811300513008200610.1074/jbc.C60001220016565519

|

|

14

|

A MukherjeeSG MartinThe thioredoxin

system: a key target in tumour and endothelial cellsBr J

Radiol81S57S68200810.1259/bjr/3418043518819999

|

|

15

|

KK RenHZ WangLP XieThe effects of oridonin

on cell growth, cell cycle, cell migration and differentiation in

melanoma cellsJ

Ethnopharmacol103176180200610.1016/j.jep.2005.07.02016169170

|

|

16

|

F GaoQ TangP YangY FangW LiY WuApoptosis

inducing and differentiation enhancement effect of oridonin on the

all-trans-retinoic acid-sensitive and -resistant acute

promyelocytic leukemia cellsInt J Lab

Hematol32e114e122201010.1111/j.1751-553X.2009.01147.x

|

|

17

|

GB ZhouH KangL WangOridonin, a diterpenoid

extracted from medicinal herbs, targets AML1-ETO fusion protein and

shows potent antitumor activity with low adverse effects on t(8;21)

leukemia in vitro and in

vivoBlood10934413450200710.1182/blood-2006-06-03225017197433

|

|

18

|

T IkezoeSS ChenXJ TongD HeberH TaguchiHP

KoefflerOridonin induces growth inhibition and apoptosis of a

variety of human cancer cellsInt J Oncol2311871193200312964003

|

|

19

|

LS MarksRS DiPaolaP NelsonPC-SPES: herbal

formulation for prostate

cancerUrology60369377200210.1016/S0090-4295(02)01913-112350462

|

|

20

|

TC HsiehEK WijeratneJY LiangAL

GunatilakaJM WuDifferential control of growth, cell cycle

progression, and expression of NF-kappaB in human breast cancer

cells MCF-7, MCF-10A, and MDA-MB-231 by ponicidin and oridonin,

diterpenoids from the chinese herb Rabdosia rubescensBiochem

Biophys Res

Commun337224231200510.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.04016176802

|

|

21

|

FH GaoXH HuW LiOridonin induces apoptosis

and senescence in colorectal cancer cells by increasing histone

hyperacetylation and regulation of p16, p21, p27 and c-mycBMC

Cancer10610201010.1186/1471-2407-10-61021054888

|

|

22

|

M PootTJ KavanaghHC KangRP HauglandPS

RabinovitchFlow cytometric analysis of cell cycle-dependent changes

in cell thiol level by combining a new laser dye with Hoechst

33342Cytometry12184187199110.1002/cyto.9901202141710962

|

|

23

|

A MachoT HirschI MarzoGlutathione

depletion is an early and calcium elevation is a late event of

thymocyte apoptosisJ Immunol1584612461919979144473

|

|

24

|

DW HedleyS ChowEvaluation of methods for

measuring cellular glutathione content using flow

cytometryCytometry15349358199410.1002/cyto.9901504118026225

|

|

25

|

MA PapiezM DybalaM Sowa-KucmaEvaluation of

oxidative status and depression-like responses in Brown Norway rats

with acute myeloid leukemiaProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol

Psychiatry33596604200910.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.02.01519268504

|

|

26

|

CA SchmittSenescence, apoptosis and

therapy - cutting the lifelines of cancerNat Rev

Cancer3286295200310.1038/nrc104412671667

|

|

27

|

P DeckerD IsenbergS MullerInhibition of

caspase-3-mediated poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) apoptotic

cleavage by human PARP autoantibodies and effect on cells

undergoing apoptosisJ Biol

Chem27590439046200010.1074/jbc.275.12.904310722754

|

|

28

|

DA GewirtzSE HoltLW ElmoreAccelerated

senescence: an emerging role in tumor cell response to chemotherapy

and radiationBiochem

Pharmacol76947957200810.1016/j.bcp.2008.06.02418657518

|

|

29

|

X DiRP ShiuIF NewshamDA GewirtzApoptosis,

autophagy, accelerated senescence and reactive oxygen in the

response of human breast tumor cells to adriamycinBiochem

Pharmacol7711391150200910.1016/j.bcp.2008.12.01619185564

|

|

30

|

KR JonesLW ElmoreC

Jackson-Cookp53-Dependent accelerated senescence induced by

ionizing radiation in breast tumour cellsInt J Radiat

Biol81445458200510.1080/0955300050016854916308915

|

|

31

|

JC BarrettLA AnnabD AlcortaG PrestonP

VojtaY YinCellular senescence and cancerCold Spring Harb Symp Quant

Biol59411418199410.1101/SQB.1994.059.01.0467587095

|

|

32

|

QA QuickDA GewirtzAn accelerated

senescence response to radiation in wild-type p53 glioblastoma

multiforme cellsJ

Neurosurg105111118200610.3171/jns.2006.105.1.11116871885

|

|

33

|

T SousaD PinhoM MoratoRole of superoxide

and hydrogen peroxide in hypertension induced by an antagonist of

adenosine receptorsEur J

Pharmacol588267276200810.1016/j.ejphar.2008.04.04418519134

|

|

34

|

YH ZhangYL WuSI TashiroS OnoderaT

IkejimaReactive oxygen species contribute to oridonin-induced

apoptosis and autophagy in human cervical carcinoma HeLa cellsActa

Pharmacol Sin3212661275201110.1038/aps.2011.9221892202

|

|

35

|

M RethHydrogen peroxide as second

messenger in lymphocyte activationNat

Immunol311291134200210.1038/ni1202-112912447370

|

|

36

|

A HolmgrenJ LuThioredoxin and thioredoxin

reductase: current research with special reference to human

diseaseBiochem Biophys Res

Commun396120124201010.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.08320494123

|