Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a major health issue and over

50,000 US residents alone are expected to die from this disease

this year (1). A crucial defect in

the vast majority of colorectal tumors is the overexpression of the

oncoprotein β-catenin. This is primarily due to the loss of the

tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), which normally

directs the intracellular destruction of β-catenin, or activating

mutations in β-catenin itself (2).

Unfortunately, knowledge on the devastating impact of these genetic

mutations has not yet translated into improved therapy.

Aside from genetic mutations, epigenetic changes are

an underlying cause of tumorigenesis. Most prominently, such

epigenetic changes involve the methylation of DNA on cytosine

residues and the modification of histones by acetylation and

methylation (3,4). In contrast to DNA methylation and

histone acetylation, the methylation of histones was only recently

validated as a major epigenetic mechanism. Methylation occurs on

lysine and arginine residues at multiple sites on histones and the

tight regulation of the histone methylation status is absolutely

required for normal cell physiology and safeguards against aberrant

cell growth. Thus, enzymes affecting histone methylation play

seminal roles in cellular homeostasis and, accordingly,

dysregulation of both histone methyltransferases as well as the

opposing demethylases is thought to be capable of inducing cancer

(5,6). However, the roles of the enzymes

determining histone methylation in colorectal tumors are largely

unexplored.

The family of human Jumonji C domain containing

proteins comprises 30 members, many of which have been shown to

function as histone demethylases (7). These include the four related

lysine-specific demethylase 4 (KDM4) proteins, KDM4A-D (8). They can demethylate histone H3 on

lysines 9 and 36 as well as histone H1.4 on lysine 26 (9–15).

Notably, KDM4A, B and C are overexpressed in human breast tumors

and promote proliferation of breast tumor cells, in part due to

their ability to function as cofactors of estrogen receptor α

(16–21). Likewise, all four KDM4 proteins

were shown to coactivate the androgen receptor and may thereby

contribute to prostate tumor formation (22–24).

Despite these examples of overlapping function, KDM4 proteins can

also behave differently from each other (8). For instance, KDM4B seems to be less

catalytically active (9,12) and is the only KDM4 protein that is

robustly overexpressed under hypoxia (25,26).

Here, we explored the role of KDM4B in colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Lentivirus mediated KDM4B downregulation

with shRNA

To generate an inducible miRshRNA entry vector,

annealed oligonucleotides KDM4B-shRNA sense

(5′-AGCGAGCGCTGACACTGTATTCTTATTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAATAAGAATACAGTGTCAGCGC-3′)

and KDM4B-shRNA antisense

(5′-GGCAGGCGCTGACACTGTATTCTTATTACATCTGTGGCTTCACTAATAAGAATACAGTGTCAGCGCT-3′)

were cloned into pEN_TTRmiRc2 (Addgene). To transfer sequences into

the lentiviral destination vector, the miRshKDM4B entry vector was

incubated together with pSLIK Hygro (Addgene) and Clonase 2

(Invitrogen) per company instructions. The resulting miRshKDM4B

lentiviral expression vector was cotransfected along with packaging

plasmids pMD2.G (Addgene), pMDL/RRE g/p (Addgene) and pRSV-Rev

(Addgene) into 293T cells. Cells were seeded at ∼60% confluence and

DNA was delivered using the polyethylenimine transfection method

overnight. Polyethylenimine to DNA ratio was 3:1. Forty-eight and

72 h post-transfection, supernatant was harvested and filtered

through a 0.45-μm membrane. Cleared viral supernatant was

concentrated using poly(ethylene glycol)-8000 and used to infect

HT-29 cells (27).

Cell proliferation assay

HT-29 cells that inducibly expressed shRNA targeting

KDM4B were seeded into 96-wells and grown in DMEM medium plus 10%

fetal calf serum. One day thereafter, the cell number was

determined for the first time and defined as number of cells at day

0. Then, cells were mock treated or with 500 ng/ml doxycycline and

cell numbers measured at the indicated days thereafter with the

TACS (Trevigen) MTT

(3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) kit

(28). Averages with standard

errors of triplicate experiments were determined.

Clonogenic assay

Cells were seeded at 5,000 cells per well.

Thereafter, cells were mock treated or with 500 ng/ml doxycycline

and grown in DMEM medium plus 10% fetal calf serum. Media without

and with doxycycline were replenished every four days for twelve

days. The cells were then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min and

stained with 1% crystal violet blue for 30 min. After rinsing with

distilled water, cells were photographed.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were grown in a

humidified atmosphere in 10% CO2 at 37°C (29). Cells were seeded into 6-cm dishes

that were coated with poly-L-lysine 12–24 h before transfection

(30). Cells were then transiently

transfected by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method

(31) and lysed 36 h after

transfection with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF,

0.25 mM Na3VO4, 0.5% Igepal CA-630, 10

μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml

pepstatin A, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.2 mM DTT. Immunoprecipitation was

performed with anti-Flag M2 or anti-Myc 9E10 monoclonal antibodies

as described (32). Coprecipitated

proteins were detected by western blotting employing enhanced

chemiluminescence (33).

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)

pull-downs

GST fusion proteins were produced in Escherichia

coli and purified as previously described (34). Cell extract containing Myc-tagged

β-catenin protein was prepared from transiently transfected 293T

cells (35). This extract was then

incubated for 3 h at 4°C with GST fusion proteins bound to

glutathione agarose beads utilizing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 50 mM

NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% Tween-20, 0.5 mM PMSF as a binding buffer.

After three washes in the same buffer, any bound Myc-tagged

β-catenin was revealed by western blotting employing anti-Myc 9E10

monoclonal antibodies.

Reporter gene assay

HT-29 cells inducibly expressing KDM4B shRNA were

infected with pBARLS lentivirus (kind gift from Dr Randall Moon)

that encodes 12 TCF4 binding elements upstream of luciferase cDNA.

Equal numbers of cells were then split into two groups of

triplicates and treated without and with 500 ng/ml doxycycline for

72 h. Then, cells were lysed as described before (36) and luciferase activities derived

from pBARLS were measured in a Berthold LB9507 luminometer

(37).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated employing TRIzol (Invitrogen) and

utilized in the Access RT-PCR kit (Promega) as described before

(38). Oligonucleotides used were

5′-GTGACCGCGACTTTTCAAAGC-3′ and 5′-CGTTGCTGGACTG GATTATCAG-3′ for

JUN, 5′-TGAGGAGACACCGCCCAC-3′ and 5′-CAACATCGATTTCTTCCTCATCTTC-3′

for MYC, 5′-AAGGCGGAGGAGACCTGCGCG-3′ and

5′-ATCGTGCGGGGTCATTGCGGC-3′ for Cyclin D1, and

5′-GAGCCACATCGCTCAGACACC-3′ and 5′-TGACAAGCTTCCGCTTCTCAGC-3′ for

GAPDH. Resulting PCR products were separated on agarose gels and

stained with ethidium bromide (39).

Chromatin immunoprecipitations

These were performed essentially as described before

(40) with rabbit KDM4B antibodies

either from Bethyl (A301-478A) in case of the JUN promoter or from

Novus Biologicals (NBP1-67802) in case of the Cyclin D1 promoter.

For promoter fragment amplification, nested PCR was employed using

the temperature program 98°C for 2 min; 8 cycles of 98°C for 30

sec, 65°C (−1°C per cycle) for 30 sec, 72°C for 25 sec; 18 cycles

(in the first PCR) or 15 cycles (in the second PCR) of 98°C for 30

sec, 57°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 25 sec (+ 1 sec per cycle), followed

by a final 4-min extension at 72°C (41). The iProof high fidelity DNA

polymerase (Bio-Rad) was used in the first PCR and GoTaq polymerase

with 5X Green buffer (Promega) in the second PCR. The primers for

the first PCR were: Jun-ChIP-2805-for

(5′-GGCAGCCACCGTCACTAGACAGTC-3′) and Jun-ChIP-3184-rev

(5′-GCCACACTCAGTGCAACTCTGAGC-3′), or D1-pro-for6

(5′-GTAACGTCACACGGACTACAGG-3′) and D1-pro-rev5

(5′-GCACACATTTGAAGTAGGACACC-3′). The primers for the second PCR

were: Jun-ChIP-2834-for (5′-CCAAGACGTCAGCCCACAATGCACC-3′) and

Jun-ChIP-3145-rev (5′-GCTCAACACTTATCTGCTACCAGTC-3′), or

D1-ChIP-2726-for (5′-GTTGCAAAGTCCTGGAGCCTCCAG-3′) and

D1-ChIP-2982-rev (5′-CGGTCGTTGAGGAGGTTGGCATCG-3′). The resultant

312 bp JUN promoter and 257 bp Cyclin D1 promoter fragments were

revealed by agarose gel electrophoresis (42).

Results

Overexpression of KDM4B in colorectal

tumors

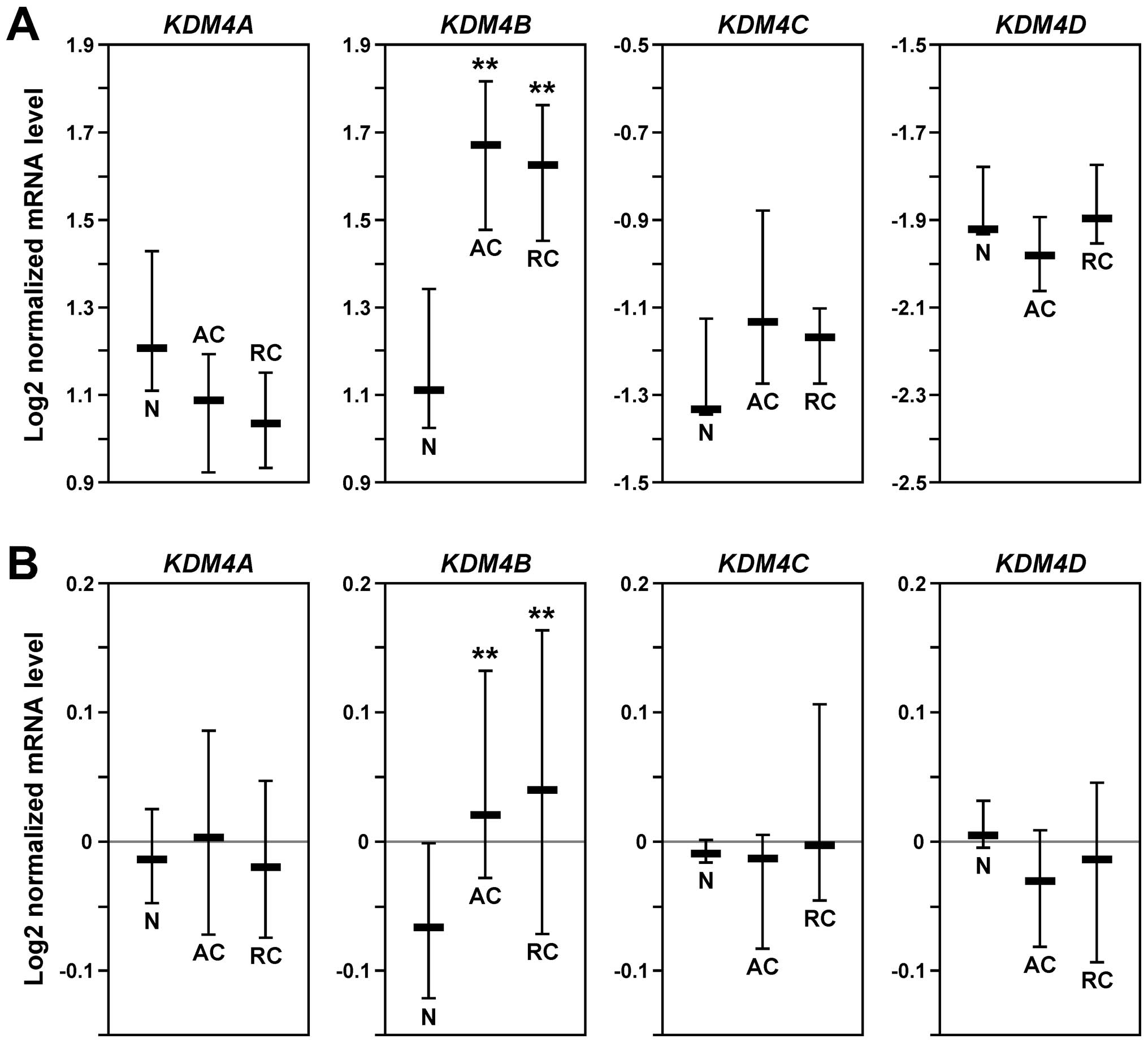

To comprehensively assess the expression pattern of

KDM4 genes in human colorectal tumors, we performed in

silico analyses comparing normal and cancer tissues with the

help of Oncomine (www.oncomine.org). In two independent

data sets (43,44), KDM4B mRNA was significantly

upregulated in both colon and rectal adenocarcinomas compared to

normal colon tissue, whereas no relevant upregulation of KDM4A,

KDM4C or KDM4D was observable (Fig.

1). These data implicate that elevated KDM4B levels, but not

overexpression of any of the other three KDM4 family members, play

a role in the development of colorectal tumors.

Growth deficit of colon cancer cells

following loss of KDM4B

To test the impact of KDM4B on cell physiology, we

infected human HT-29 colon cancer cells with lentivirus that

doxycycline-inducibly expressed KDM4B shRNA. After selection for

viral integration, these cells were treated with and without

doxycycline, which resulted in efficient downregulation of KDM4B

(Fig. 2A). Importantly,

doxycycline treatment significantly reduced HT-29 cell growth

(Fig. 2A), suggesting that KDM4B

has a pro-growth effect. We also determined the importance of KDM4B

for growing colonies from single cells, another litmus test for

oncogenic activity. When treated with doxycycline to ablate KDM4B

expression, HT-29 cells displayed a markedly reduced ability to

establish colonies (Fig. 2B).

Altogether, these results support the notion that KDM4B promotes

neoplastic growth of colon cells.

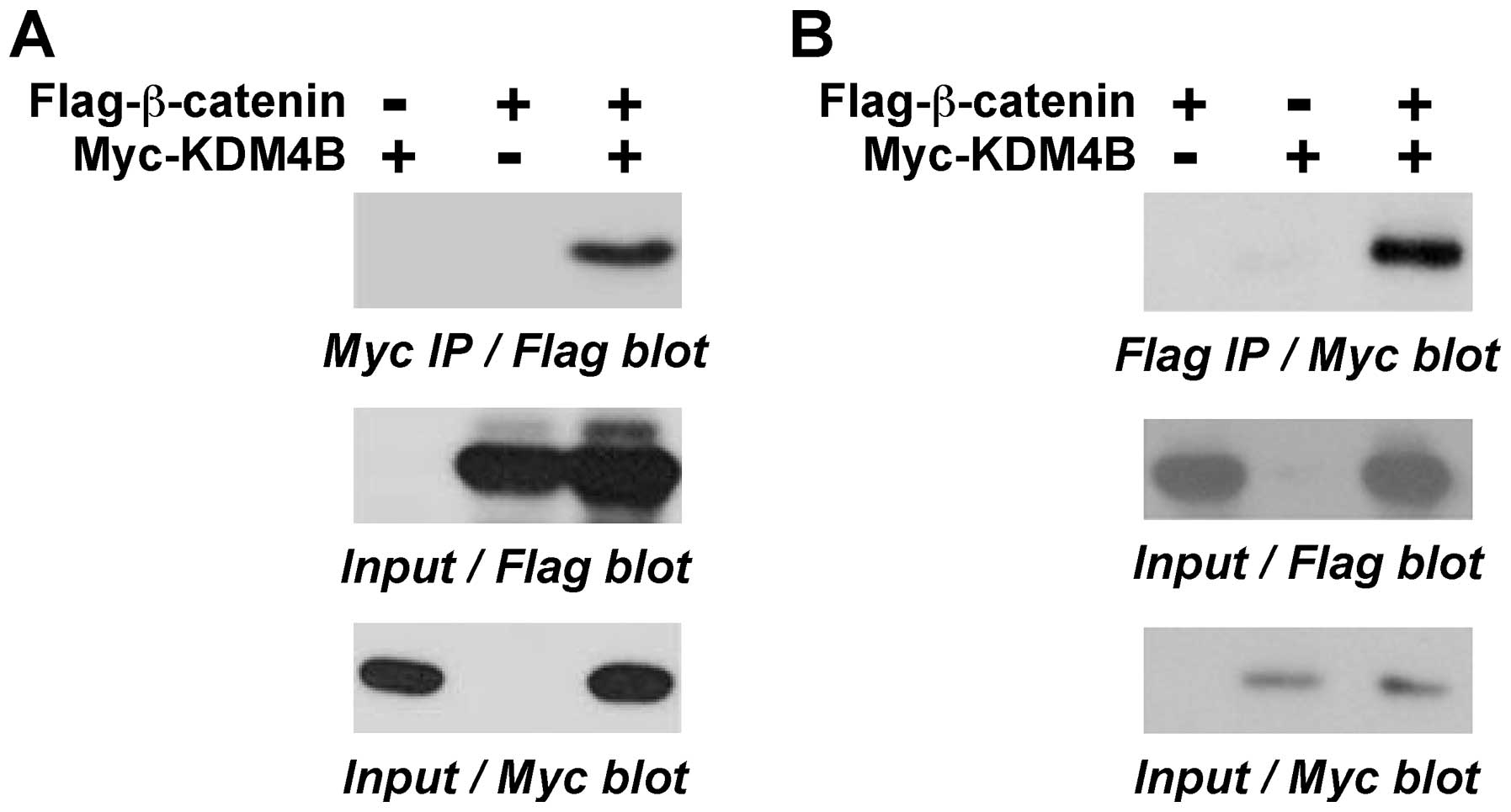

Complex formation of KDM4B with

β-catenin

Overexpression of the β-catenin oncoprotein, the

linchpin of colon tumorigenesis, is observed in >80% of sporadic

colorectal tumors (2). Like KDM4B,

β-catenin is a transcriptional cofactor (45). Therefore, we tested whether KDM4B

might interact with β-catenin. To this end, we coexpressed

Flag-tagged β-catenin with Myc-tagged KDM4B in 293T cells and

performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. We found that

β-catenin coprecipitated with KDM4B (Fig. 3A). Similarly, in a reverse order

coimmunoprecipitation experiment, KDM4B coprecipitated with

β-catenin (Fig. 3B). These data

demonstrate that KDM4B and β-catenin form complexes in

vivo.

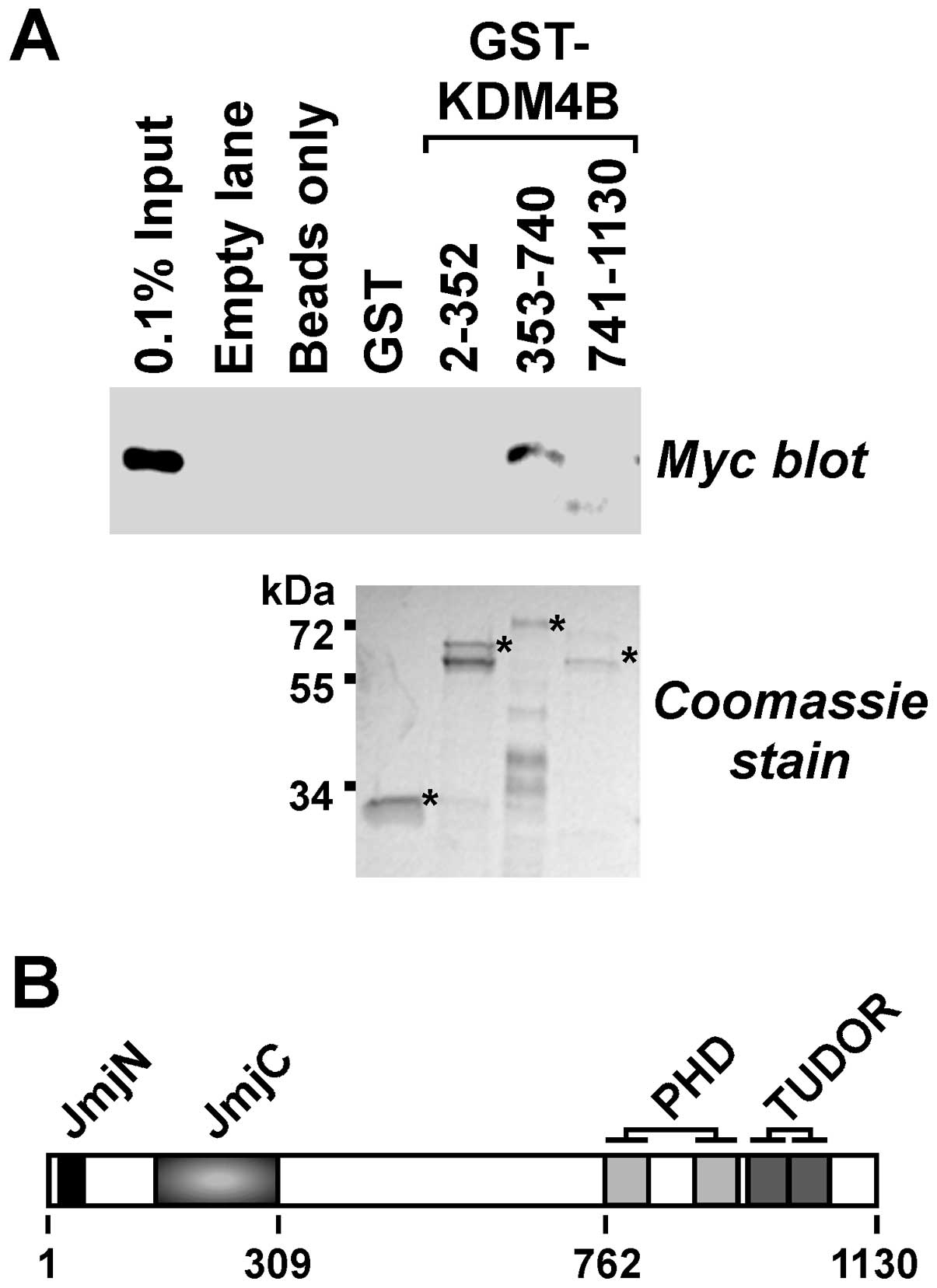

Next, we explored whether β-catenin would bind to

KDM4B in vitro and which domains of KDM4B would be involved.

To this end, we divided KDM4B into three parts and purified

respective GST fusion proteins. These were then bound to

glutathione agarose beads, which were subsequently incubated with a

cell extract containing Myc-tagged β-catenin. No binding of

β-catenin to the GST moiety itself was detectable, but it

interacted with KDM4B amino acids 353–740 (Fig. 4A). These amino acids are devoid of

any known structural motifs (Fig.

4B). In contrast, β-catenin did not appreciably bind to the

N-terminal KDM4B amino acids 2–352 encompassing the catalytic JmjC

and JmjN domains or the C-terminal amino acids 741–1130, which

contain the double PHD and TUDOR domains that are involved in

recognizing methylated histone residues (8,46).

Collectively, our data reveal that KDM4B and β-catenin interact

both in vitro and in vivo.

Coactivation of gene transcription by

KDM4B

The β-catenin protein itself does not directly bind

to DNA. Rather, it is primarily recruited to chromatin in the

intestine by the DNA-binding transcription factor TCF4 (47). Therefore, we reasoned that not only

β-catenin, but also TCF4 might form a complex with KDM4B. To test

this hypothesis, we coexpressed Flag-tagged KDM4B and Myc-tagged

TCF4 in 293T cells, immunoprecipitated with Flag antibodies and

then tested for coprecipitated TCF4 by anti-Myc western blotting.

Indeed, TCF4 coprecipitated with KDM4B (Fig. 5A), implicating that a tripartite

complex of TCF4, β-catenin and KDM4B can be formed.

To determine whether KDM4B stimulates or represses

β-catenin/TCF4-dependent transcription, we employed a TOPflash

luciferase reporter system that specifically measures

β-catenin/TCF4-dependent transcription in colon cells (48). A lentiviral vector was employed to

stably introduce the luciferase reporter gene into our HT-29 colon

cancer cells that doxycycline-inducibly expressed KDM4B shRNA. In

the absence of doxycycline, high luciferase activity was expectedly

observable (Fig. 5B). However,

upon depletion of KDM4B after doxycyline treatment, luciferase

activity was ∼3-fold reduced, indicating that KDM4B can stimulate

β-catenin/TCF4-dependent gene transcription.

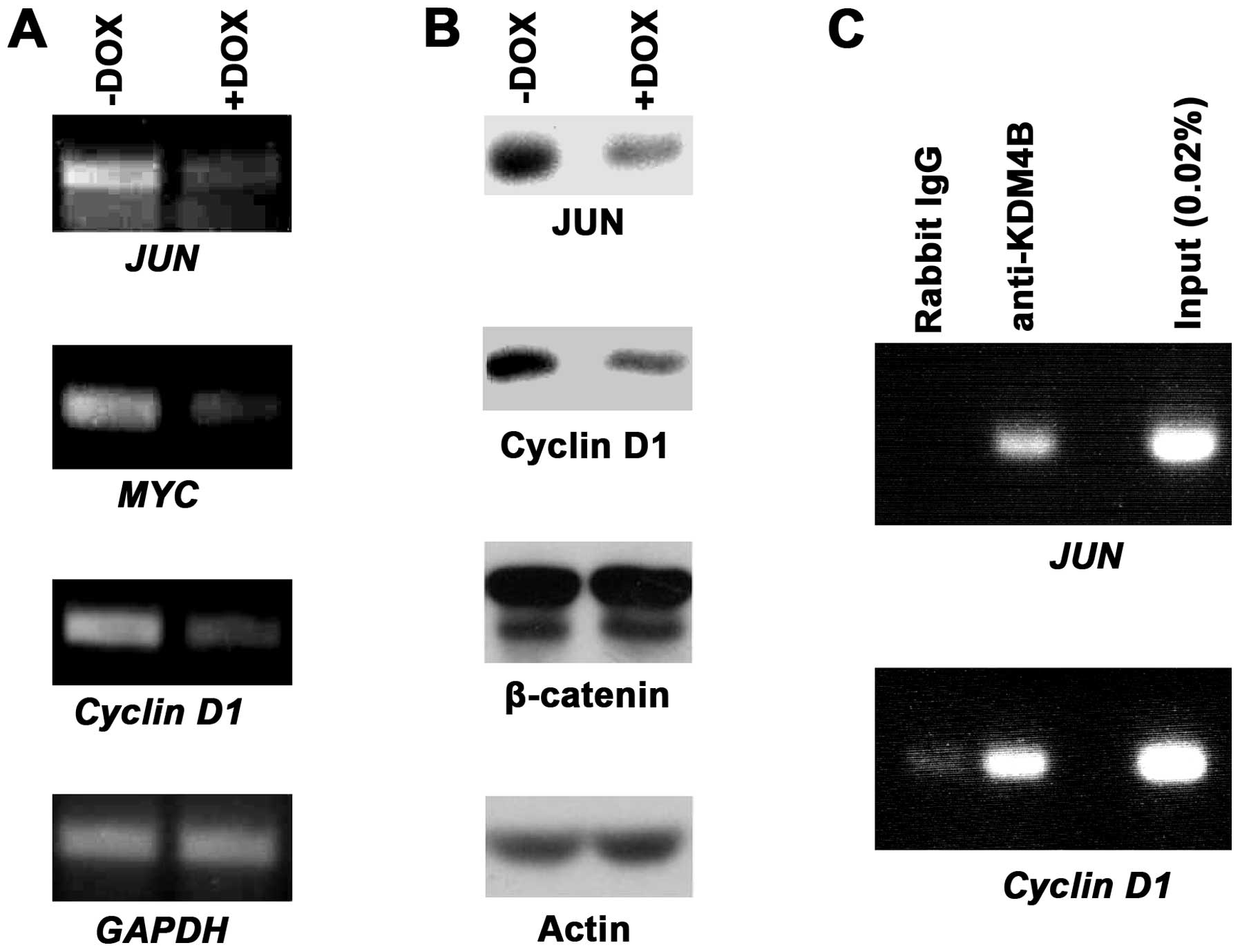

We next sought to assess how endogenous target genes

of β-catenin/TCF4 would be affected by KDM4B downregulation.

Specifically, we studied three oncogenes encoding the JUN or MYC

transcription factor or the cell cycle regulator Cyclin D1, all of

which are bona fide targets of β-catenin/TCF4 (48–51).

When utilizing our doxycycline-inducible KDM4B shRNA expressing

HT-29 cells, we observed that JUN, MYC and Cyclin D1 transcription

became reduced upon KDM4B downregulation, whereas the control GAPDH

was unaffected (Fig. 6A). In

addition, western blotting showed that this also held true at the

protein level for JUN and Cyclin D1 (Fig. 6B), whereas MYC protein expression

was below our detection level (not shown); as controls, neither

β-catenin nor actin protein levels were affected by KDM4B

downregulation (Fig. 6B).

Finally, we assessed whether KDM4B would bind to the

JUN or Cyclin D1 gene promoter. To this end, we performed chromatin

immunoprecipitation experiments. While control IgG antibodies

barely or not at all led to precipitation of promoter fragments,

KDM4B antibodies were able to robustly precipitate both JUN and

Cyclin D1 promoter fragments (Fig.

6C). This indicates that JUN and Cyclin D1 are directly

regulated by KDM4B. Altogether, our data provide evidence that

KDM4B coactivates β-catenin/TCF4-dependent gene transcription.

Discussion

The data described in this report provide novel

information. First, we discovered that the KDM4B histone

demethylase is appreciably upregulated at the mRNA level in

colorectal tumors, whereas none of the other three KDM4 family

members is. Second, we showed that growth and colony formation

ability of HT-29 colon cancer cells is stimulated by KDM4B, and

third, we revealed that KDM4B is capable of forming complexes with

β-catenin and TCF4 and can thereby enhance transcription of

oncogenes such as JUN, MYC and Cyclin D1. Altogether, these data

strongly suggest that KDM4B has oncogenic properties in colorectal

cells.

KDM4B is a histone demethylase that especially

demethylates trimethylated H3K9, H3K36 and H1.4K26 (9,12,14).

In general, both trimethylated H3K9 and H1.4K26 at a gene promoter

are associated with a transcriptionally repressed status of

chromatin (52,53), providing an explanation how KDM4B

may stimulate gene transcription by removing these repressive

marks. On the other hand, trimethylated H3K36 has a variety of

functions: it may promote transcription elongation but suppress

transcription initiation at the promoter (54). Thus, the net effect on gene

expression upon removal of H3K36 trimethylation by KDM4B is

debatable. However, since KDM4 proteins appear to more efficiently

target H3K9 than H3K36 (8), it is

likely that the effect of KDM4B on gene transcription is primarily

governed by its ability to demethylate trimethylated H3K9 (and

H1.4K26) and accordingly KDM4B overexpression should result in

enhanced transcription of target genes like JUN, MYC and Cyclin

D1.

MYC and JUN encode for DNA-binding transcription

factors and are prominent oncogenes (55,56).

They are also β-catenin target genes (48,49)

and upregulated in human colorectal tumors (57,58).

Interestingly, JUN can form complexes with β-catenin and TCF4,

which stabilizes the β-catenin/TCF4 complex and enhances β-catenin

dependent transcription (59,60).

Furthermore, a dominant-negative version of JUN was able to

suppress the tumorigenic potential of HT-29 colon cancer cells and

JUN inactivation also reduced gastrointestinal tumor formation in

the APCMin mouse model, in which inactivation of APC

leads to β-catenin overexpression (59,61).

Likewise, the cell cycle regulator Cyclin D1 is upregulated in

colorectal tumors (62) and its

ablation suppressed tumor formation in APCMin mice

(63). Thus, stimulation of JUN,

MYC and Cyclin D1 expression by KDM4B is predicted to promote

colorectal tumor formation.

Cooperation with β-catenin may not be the only

mechanism by which KDM4B contributes to the causation of colorectal

cancer. Recently, it was reported that KDM4B is involved in the

stimulation of hypoxia-inducible genes in colon cancer (64). Possibly, this may involve complex

formation of KDM4B with the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, the master

mediator of the hypoxic response, since a relative of KDM4B, the

KDM4C protein, can actually bind to hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

(65). Moreover, KDM4A is capable

of binding to the p53 tumor suppressor in colon cancer cells and

inhibit p53-dependent transcription (66), raising the possibility that also

KDM4B might do so.

Apart from transcription regulation, KDM4B is also

involved in DNA repair. Its TUDOR domains can bind to dimethylated

H4K20, which normally recruits 53BP1 to sites of DNA damage and

thereby facilitates repair. Notably, this activity of KDM4B is

independent of its enzymatic activity (67). Accordingly, KDM4B overexpression

could impair DNA repair by preventing the recruitment of 53BP1 and

thereby induce genomic instability, another mechanism by which

KDM4B could contribute to tumor formation. However, a recent report

posits that KDM4B enhances DNA repair in a manner dependent on its

enzymatic activity and thus promotes cell survival (68). This may be relevant during therapy,

when KDM4B overexpression could help cancer cells to repair the DNA

damage caused by radiotherapy and many chemotherapeutic agents.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the pro-growth

function of KDM4B in colorectal tumors and provided a mechanism by

which KDM4B may attain this through interaction with

β-catenin/TCF4. Given that β-catenin is involved in many other

types of cancer (2,45), including breast and bladder cancer

where KDM4B is also overexpressed (18,69,70),

the oncogenic functions of KDM4B may be of widespread importance.

Thus, inhibition of KDM4B enzymatic activity or preventing its

interaction with β-catenin by small molecule drugs, similar to the

inhibition of chromatin recruitment of the BRD4 epigenetic

regulator in acute myeloid leukemia (71,72),

may hold promise in cancer therapy.

References

|

1.

|

Siegel R, Naishadham D and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 63:11–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2.

|

Clevers H: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in

development and disease. Cell. 127:469–480. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Chi P, Allis CD and Wang GG: Covalent

histone modifications--miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in

human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 10:457–469. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Kulis M and Esteller M: DNA methylation

and cancer. Adv Genet. 70:27–56. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5.

|

Dawson MA and Kouzarides T: Cancer

epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 150:12–27. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Black JC, Van Rechem C and Whetstine JR:

Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and

biological impact. Mol Cell. 48:491–507. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7.

|

Kooistra SM and Helin K: Molecular

mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 13:297–311. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Berry WL and Janknecht R: KDM4/JMJD2

histone demethylases: epigenetic regulators in cancer cells. Cancer

Res. 73:2936–2942. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Whetstine JR, Nottke A, Lan F, Huarte M,

Smolikov S, Chen Z, Spooner E, Li E, Zhang G, Colaiacovo M and Shi

Y: Reversal of histone lysine trimethylation by the JMJD2 family of

histone demethylases. Cell. 125:467–481. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, Maiolica

A, Rappsilber J, Antal T, Hansen KH and Helin K: The putative

oncogene GASC1 demethylates tri- and dimethylated lysine 9 on

histone H3. Nature. 442:307–311. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Klose RJ, Yamane K, Bae Y, Zhang D,

Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wong J and Zhang Y: The

transcriptional repressor JHDM3A demethylates trimethyl histone H3

lysine 9 and lysine 36. Nature. 442:312–316. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12.

|

Fodor BD, Kubicek S, Yonezawa M,

O’Sullivan RJ, Sengupta R, Perez-Burgos L, Opravil S, Mechtler K,

Schotta G and Jenuwein T: Jmjd2b antagonizes H3K9 trimethylation at

pericentric heterochromatin in mammalian cells. Genes Dev.

20:1557–1562. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Shin S and Janknecht R: Diversity within

the JMJD2 histone demethylase family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

353:973–977. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Trojer P, Zhang J, Yonezawa M, Schmidt A,

Zheng H, Jenuwein T and Reinberg D: Dynamic histone H1 isotype 4

methylation and demethylation by histone lysine methyltransferase

G9a/KMT1C and the Jumonji domain-containing JMJD2/KDM4 proteins. J

Biol Chem. 284:8395–8405. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Weiss T, Hergeth S, Zeissler U, Izzo A,

Tropberger P, Zee BM, Dundr M, Garcia BA, Daujat S and Schneider R:

Histone H1 variant-specific lysine methylation by G9a/KMT1C and

Glp1/KMT1D. Epigenetics Chromatin. 3:72010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Liu G, Bollig-Fischer A, Kreike B, van de

Vijver MJ, Abrams J, Ethier SP and Yang ZQ: Genomic amplification

and oncogenic properties of the GASC1 histone demethylase gene in

breast cancer. Oncogene. 28:4491–4500. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Yang J, Jubb AM, Pike L, Buffa FM, Turley

H, Baban D, Leek R, Gatter KC, Ragoussis J and Harris AL: The

histone demethylase JMJD2B is regulated by estrogen receptor alpha

and hypoxia, and is a key mediator of estrogen induced growth.

Cancer Res. 70:6456–6466. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Kawazu M, Saso K, Tong KI, McQuire T, Goto

K, Son DO, Wakeham A, Miyagishi M, Mak TW and Okada H: Histone

demethylase JMJD2B functions as a co-factor of estrogen receptor in

breast cancer proliferation and mammary gland development. PLoS

One. 6:e178302011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Shi L, Sun L, Li Q, Liang J, Yu W, Yi X,

Yang X, Li Y, Han X, Zhang Y, Xuan C, Yao Z and Shang Y: Histone

demethylase JMJD2B coordinates H3K4/H3K9 methylation and promotes

hormonally responsive breast carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 108:7541–7546. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Berry WL, Shin S, Lightfoot SA and

Janknecht R: Oncogenic features of the JMJD2A histone demethylase

in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 41:1701–1706. 2012.

|

|

21.

|

Gaughan L, Stockley J, Coffey K, O’Neill

D, Jones DL, Wade M, Wright J, Moore M, Tse S, Rogerson L and

Robson CN: KDM4B is a master regulator of the estrogen receptor

signalling cascade. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:6892–6904. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22.

|

Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Greschik H,

Fodor BD, Jenuwein T, Vogler C, Schneider R, Gunther T, Buettner R,

Metzger E and Schule R: Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and

LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat Cell

Biol. 9:347–353. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23.

|

Shin S and Janknecht R: Activation of

androgen receptor by histone demethylases JMJD2A and JMJD2D.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 359:742–746. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Coffey K, Rogerson L, Ryan-Munden C,

Alkharaif D, Stockley J, Heer R, Sahadevan K, O’Neill D, Jones D,

Darby S, Staller P, Mantilla A, Gaughan L and Robson CN: The lysine

demethylase, KDM4B, is a key molecule in androgen receptor

signalling and turnover. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:4433–4446. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Pollard PJ, Loenarz C, Mole DR, McDonough

MA, Gleadle JM, Schofield CJ and Ratcliffe PJ: Regulation of

Jumonji-domain-containing histone demethylases by hypoxia-inducible

factor (HIF)-1alpha. Biochem J. 416:387–394. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Beyer S, Kristensen MM, Jensen KS,

Johansen JV and Staller P: The histone demethylases JMJD1A and

JMJD2B are transcriptional targets of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF.

J Biol Chem. 283:36542–36552. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27.

|

Kim TD, Oh S, Shin S and Janknecht R:

Regulation of tumor suppressor p53 and HCT116 cell physiology by

histone demethylase JMJD2D/KDM4D. PLoS One. 7:e346182012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28.

|

Oh S, Shin S, Lightfoot SA and Janknecht

R: 14-3-3 proteins modulate the ETS transcription factor ETV1 in

prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 73:5110–5119. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29.

|

Mooney SM, Grande JP, Salisbury JL and

Janknecht R: Sumoylation of p68 and p72 RNA helicases affects

protein stability and transactivation potential. Biochemistry.

49:1–10. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Janknecht R: Regulation of the ER81

transcription factor and its coactivators by mitogen- and

stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1). Oncogene. 22:746–755.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Dowdy SC, Mariani A and Janknecht R:

HER2/Neu- and TAK1-mediated up-regulation of the transforming

growth factor beta inhibitor Smad7 via the ETS protein ER81. J Biol

Chem. 278:44377–44384. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32.

|

Goel A and Janknecht R: Concerted

activation of ETS protein ER81 by p160 coactivators, the

acetyltransferase p300 and the receptor tyrosine kinase HER2/Neu. J

Biol Chem. 279:14909–14916. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Papoutsopoulou S and Janknecht R:

Phosphorylation of ETS transcription factor ER81 in a complex with

its coactivators CREB-binding protein and p300. Mol Cell Biol.

20:7300–7310. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Knebel J, De Haro L and Janknecht R:

Repression of transcription by TSGA/Jmjd1a, a novel interaction

partner of the ETS protein ER71. J Cell Biochem. 99:319–329. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35.

|

Wu J and Janknecht R: Regulation of the

ETS transcription factor ER81 by the 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase 1

and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 277:42669–42679. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36.

|

Rossow KL and Janknecht R: The Ewing’s

sarcoma gene product functions as a transcriptional activator.

Cancer Res. 61:2690–2695. 2001.

|

|

37.

|

Mooney SM, Goel A, D’Assoro AB, Salisbury

JL and Janknecht R: Pleiotropic effects of p300-mediated

acetylation on p68 and p72 RNA helicase. J Biol Chem.

285:30443–30452. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38.

|

Goel A and Janknecht R:

Acetylation-mediated transcriptional activation of the ETS protein

ER81 by p300, P/CAF, and HER2/Neu. Mol Cell Biol. 23:6243–6254.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39.

|

Oh S and Janknecht R: Histone demethylase

JMJD5 is essential for embryonic development. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 420:61–65. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Shin S, Oh S, An S and Janknecht R: ETS

variant 1 regulates matrix metalloproteinase-7 transcription in

LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 29:306–314. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

DiTacchio L, Bowles J, Shin S, Lim DS,

Koopman P and Janknecht R: Transcription factors ER71/ETV2 and SOX9

participate in a positive feedback loop in fetal and adult mouse

testis. J Biol Chem. 287:23657–23666. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Shin S, Kim TD, Jin F, van Deursen JM,

Dehm SM, Tindall DJ, Grande JP, Munz JM, Vasmatzis G and Janknecht

R: Induction of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and modulation

of androgen receptor by ETS variant 1/ETS-related protein 81.

Cancer Res. 69:8102–8110. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43.

|

Kaiser S, Park YK, Franklin JL, Halberg

RB, Yu M, Jessen WJ, Freudenberg J, Chen X, Haigis K, Jegga AG,

Kong S, Sakthivel B, Xu H, Reichling T, Azhar M, Boivin GP, Roberts

RB, Bissahoyo AC, Gonzales F, Bloom GC, Eschrich S, Carter SL,

Aronow JE, Kleimeyer J, Kleimeyer M, Ramaswamy V, Settle SH, Boone

B, Levy S, Graff JM, Doetschman T, Groden J, Dove WF, Threadgill

DW, Yeatman TJ, Coffey RJ Jr and Aronow BJ: Transcriptional

recapitulation and subversion of embryonic colon development by

mouse colon tumor models and human colon cancer. Genome Biol.

8:R1312007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44.

|

Kurashina K, Yamashita Y, Ueno T, Koinuma

K, Ohashi J, Horie H, Miyakura Y, Hamada T, Haruta H, Hatanaka H,

Soda M, Choi YL, Takada S, Yasuda Y, Nagai H and Mano H: Chromosome

copy number analysis in screening for prognosis-related genomic

regions in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 99:1835–1840. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45.

|

Clevers H and Nusse R: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling and disease. Cell. 149:1192–1205. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46.

|

Yap KL and Zhou MM: Keeping it in the

family: diverse histone recognition by conserved structural folds.

Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 45:488–505. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47.

|

Mosimann C, Hausmann G and Basler K:

Beta-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene

activation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10:276–286. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48.

|

He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H,

Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B and Kinzler KW:

Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science.

281:1509–1512. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49.

|

Mann B, Gelos M, Siedow A, Hanski ML,

Gratchev A, Ilyas M, Bodmer WF, Moyer MP, Riecken EO, Buhr HJ and

Hanski C: Target genes of beta-catenin-T

cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor signaling in human colorectal

carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 96:1603–1608. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50.

|

Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I,

Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R and Ben-Ze’ev A: The Cyclin D1

gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 96:5522–5527. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51.

|

Tetsu O and McCormick F: Beta-catenin

regulates expression of Cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature.

398:422–426. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52.

|

Kouzarides T: Chromatin modifications and

their function. Cell. 128:693–705. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53.

|

Daujat S, Zeissler U, Waldmann T, Happel N

and Schneider R: HP1 binds specifically to Lys26-methylated histone

H1.4, whereas simultaneous Ser27 phosphorylation blocks HP1

binding. J Biol Chem. 280:38090–38095. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54.

|

Wagner EJ and Carpenter PB: Understanding

the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 13:115–126. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55.

|

Eilers M and Eisenman RN: Myc’s broad

reach. Genes Dev. 22:2755–2766. 2008.

|

|

56.

|

Eferl R and Wagner EF: AP-1: a

double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:859–868.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57.

|

Smith DR, Myint T and Goh HS:

Over-expression of the c-myc proto-oncogene in colorectal

carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 68:407–413. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58.

|

Magrisso IJ, Richmond RE, Carter JH, Pross

CB, Gilfillen RA and Carter HW: Immunohistochemical detection of

RAS, JUN, FOS, and p53 oncoprotein expression in human colorectal

adenomas and carcinomas. Lab Invest. 69:674–681. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59.

|

Nateri AS, Spencer-Dene B and Behrens A:

Interaction of phosphorylated c-Jun with TCF4 regulates intestinal

cancer development. Nature. 437:281–285. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60.

|

Gan XQ, Wang JY, Xi Y, Wu ZL, Li YP and Li

L: Nuclear Dvl, c-Jun, beta-catenin, and TCF form a complex leading

to stabilization of beta-catenin-TCF interaction. J Cell Biol.

180:1087–1100. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61.

|

Suto R, Tominaga K, Mizuguchi H, Sasaki E,

Higuchi K, Kim S, Iwao H and Arakawa T: Dominant-negative mutant of

c-Jun gene transfer: a novel therapeutic strategy for colorectal

cancer. Gene Ther. 11:187–193. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62.

|

Bartkova J, Lukas J, Strauss M and Bartek

J: The PRAD-1/Cyclin D1 oncogene product accumulates aberrantly in

a subset of colorectal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 58:568–573. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63.

|

Hulit J, Wang C, Li Z, Albanese C, Rao M,

Di Vizio D, Shah S, Byers SW, Mahmood R, Augenlicht LH, Russell R

and Pestell RG: Cyclin D1 genetic heterozygosity regulates colonic

epithelial cell differentiation and tumor number in ApcMin mice.

Mol Cell Biol. 24:7598–7611. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64.

|

Fu L, Chen L, Yang J, Ye T, Chen Y and

Fang J: HIF-1alpha-induced histone demethylase JMJD2B contributes

to the malignant phenotype of colorectal cancer cells via an

epigenetic mechanism. Carcinogenesis. 33:1664–1673. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65.

|

Luo W, Chang R, Zhong J, Pandey A and

Semenza GL: Histone demethylase JMJD2C is a coactivator for

hypoxia-inducible factor 1 that is required for breast cancer

progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:E3367–E3376. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66.

|

Kim TD, Shin S, Berry WL, Oh S and

Janknecht R: The JMJD2A demethylase regulates apoptosis and

proliferation in colon cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 113:1368–1376.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67.

|

Mallette FA, Mattiroli F, Cui G, Young LC,

Hendzel MJ, Mer G, Sixma TK and Richard S: RNF8- and

RNF168-dependent degradation of KDM4A/JMJD2A triggers 53BP1

recruitment to DNA damage sites. EMBO J. 31:1865–1878. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68.

|

Young LC, McDonald DW and Hendzel MJ:

Kdm4b histone demethylase is a DNA damage response protein and

confers a survival advantage following gamma-irradiation. J Biol

Chem. 288:21376–21388. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69.

|

Slee RB, Steiner CM, Herbert BS, Vance GH,

Hickey RJ, Schwarz T, Christan S, Radovich M, Schneider BP,

Schindelhauer D and Grimes BR: Cancer-associated alteration of

pericentromeric heterochromatin may contribute to chromosome

instability. Oncogene. 31:3244–3253. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70.

|

Toyokawa G, Cho HS, Iwai Y, Yoshimatsu M,

Takawa M, Hayami S, Maejima K, Shimizu N, Tanaka H, Tsunoda T,

Field HI, Kelly JD, Neal DE, Ponder BA, Maehara Y, Nakamura Y and

Hamamoto R: The histone demethylase JMJD2B plays an essential role

in human carcinogenesis through positive regulation of

cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Cancer Prev Res. 4:2051–2061. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71.

|

Dawson MA, Prinjha RK, Dittmann A,

Giotopoulos G, Bantscheff M, Chan WI, Robson SC, Chung CW, Hopf C,

Savitski MM, Huthmacher C, Gudgin E, Lugo D, Beinke S, Chapman TD,

Roberts EJ, Soden PE, Auger KR, Mirguet O, Doehner K, Delwel R,

Burnett AK, Jeffrey P, Drewes G, Lee K, Huntly BJ and Kouzarides T:

Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective

treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature. 478:529–533. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72.

|

Zuber J, Shi J, Wang E, Rappaport AR,

Herrmann H, Sison EA, Magoon D, Qi J, Blatt K, Wunderlich M, Taylor

MJ, Johns C, Chicas A, Mulloy JC, Kogan SC, Brown P, Valent P,

Bradner JE, Lowe SW and Vakoc CR: RNAi screen identifies Brd4 as a

therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 478:524–528.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|