Introduction

During cancer development, cell proliferation rates

exceed blood vessel formation, leading to hypoxia in solid tumor

microenvironment, which is a hallmark of highly proliferative tumor

cells (1). Proliferating cancer

cells proliferate using ‘the Warburg effect’, which consists in

increased glucose uptake and metabolism through anaerobic

glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation (2), a process in part controlled by the

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a master regulator of cellular

energy pools (3). In addition,

AMPK is tightly linked to cancer by its ability to induce the

phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor p53, leading to DNA

synthesis inhibition (4) and cell

cycle arrest through inhibition of the mammalian target of

rapamycin (mTOR) (5).

Hypoxic exposure leads to an increase in

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), a transcription factor

essential in cell adaptation/survival (6). Whereas the HIF-1α protein is rapidly

degraded under normal (21%) oxygen conditions, hypoxia increases

HIF-1α levels and transcriptional activity, which then promotes the

expression of a number of genes necessary for cancer cell survival

(7).

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript

1 (Malat1), also named nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 2, is a

conserved long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) ubiquitously expressed

(8). High levels of Malat1 were

initially associated to the severity of lung metastasis (8), but this observation has since been

extended to many other types of tumors (9–13).

Malat1 appears to stimulate cell proliferation at the expense of

differentiation and senescence (13–15).

Malat1−/− mouse xenografts show a nearly 80% lower tumor

development in vivo (10),

possibly through modification of serine/arginine splicing factors

(16).

Genetic loss of Malat1 does not affect mouse

viability (17); however, Malat1

has been suggested to modulate angiogenesis in vivo

(18). Interestingly, hypoxia

upregulates Malat1 in vitro (18,19),

and mice directly exposed to hypoxia also show increased Malat1

expression levels in specific tissues such as proximal tubules

(19). Based on these findings, it

is thus likely that the increase in Malat1 expression is part of an

adaptive response to hypoxia. The aim of this study was thus to

mechanistically investigate the pathways that contribute to the

transcriptional stimulation in Malat1 levels in cells under

hypoxia. Our results show that AMPK, through its upstream

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK), is a

major node triggering Malat1 transcription upon hypoxia in a

HIF-1α-dependent manner.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

HeLa and HEK293T cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA,

USA). Cells were grown in DMEM containing 1 g/l glucose, 10% FBS, 2

mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Compounds

(Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, USA) were suspended in the

appropriate vehicle (DMSO or medium without FBS). A pCDNA3

expression plasmid containing the human HIF-1α cDNA was purchased

from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Oxygen conditions

Hypoxic conditions were maintained in a humidified

variable aerobic workstation (Coy Laboratory) at 37°C. To induce

hypoxia, oxygen concentrations were reduced from 21 to 1.5%, while

carbon dioxide remained at 5%. Oxygen sensor continuously monitored

and adjusted the oxygen level during experiments.

Cloning of the human Malat1 promoter

The Malat1 promoter was amplified from human genomic

DNA by PCR using primers 5′-TGTGGGAGCTTTTCAGTATTC-3′ and

5′-CTGGAATGGCCAGCCTATAA-3′, effectively resulting in a fragment

containing a sequence of 5.6 kb directly upstream of the Malat1

gene initiation site. The fragment was first subcloned in

TOPO®XL vector (Thermofisher) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions, and then cloned in

KpnI/XhoI-digested pGL3 luciferase reporter vector

(Promega). Validity of this construct was confirmed by

sequencing.

Gene reporter assays

HEK293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 80%

confluence. Six hours later, cells were transfected for 12 h with

250 ng of the reporter vector (hMALAT1_prom-pGL3 or

p(HA)HIF-1α-pCDNA3) and 50 ng of a β-galactosidase expression

vector as described previously (20). Transfected cells were FBS-starved

for 2 h before any pharmacological treatment. Luciferase activity

and β-galactosidase activity were measured as described previously

(20) using a Luminoskan™ Ascent

microplate luminometer or a Multiskan Spectrum (Thermo Scientific),

respectively. Luciferase activity levels were normalized against

β-galactosidase activity levels. The figures represent the mean

fold activation ± SEM of at least three independent gene reporter

experiments.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

Whole cell RNA extracts were prepared as recommended

by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare). DNA reverse transcription was

prepared with 0.5 μg of total RNA using qScript™ cDNA Synthesis kit

(Quanta Biosciences). Quantitative PCR were performed on a 7900HT

Applied Biosystems, using Sybr™-Green detection (Sigma-Aldrich),

normalized to a housekeeping gene. The following nucleotide pairs

were used to amplify Malat1: forward, GTAATGGAAAGTAAAGCCCTGAAC and

reverse, CCCCGGAACTTTTAAAATACCTCT.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell proteins were extracted by lysis with an

extraction buffer containing NP40 0.04%, Tween 0.02%, sodium

orthovanadate 1.5 mM and 10% protease inhibitors (Roche), and

incubated 10 min on ice. After centrifugation, the supernatant was

collected and considered as whole cell extract. Protein

concentrations were determined with DC™ Protein Assay Reagent

(Bio-Rad). Proteins (50 μg) per lane were loaded onto a 7.5%

SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and then blotted with

Trans-Blot® Turbo™ (Bio-Rad) on PVDF membranes.

Membranes were saturated in fat-free dry milk for 1 h, and then

incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in recommended

buffer at recommended dilutions (anti-HIF-1α from R&D,

anti-phospho-Thr172 AMPK and anti-AMPK total from Cell Signaling,

anti-β-actin from Millipore). Membranes were then incubated with

secondary antibodies coupled with HRP for 1 h (from Santa-Cruz for

anti-goat-HRP, from GE Healthcare for anti-mouse-HRP and

anti-rabbit-HRP). Signals were detected with ECL™ Western Blotting

Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare) on Kodak film.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three

independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed

by one or two-way ANOVA as appropriate. A value of p<0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

Hypoxia induces Malat1 expression through

AMPK

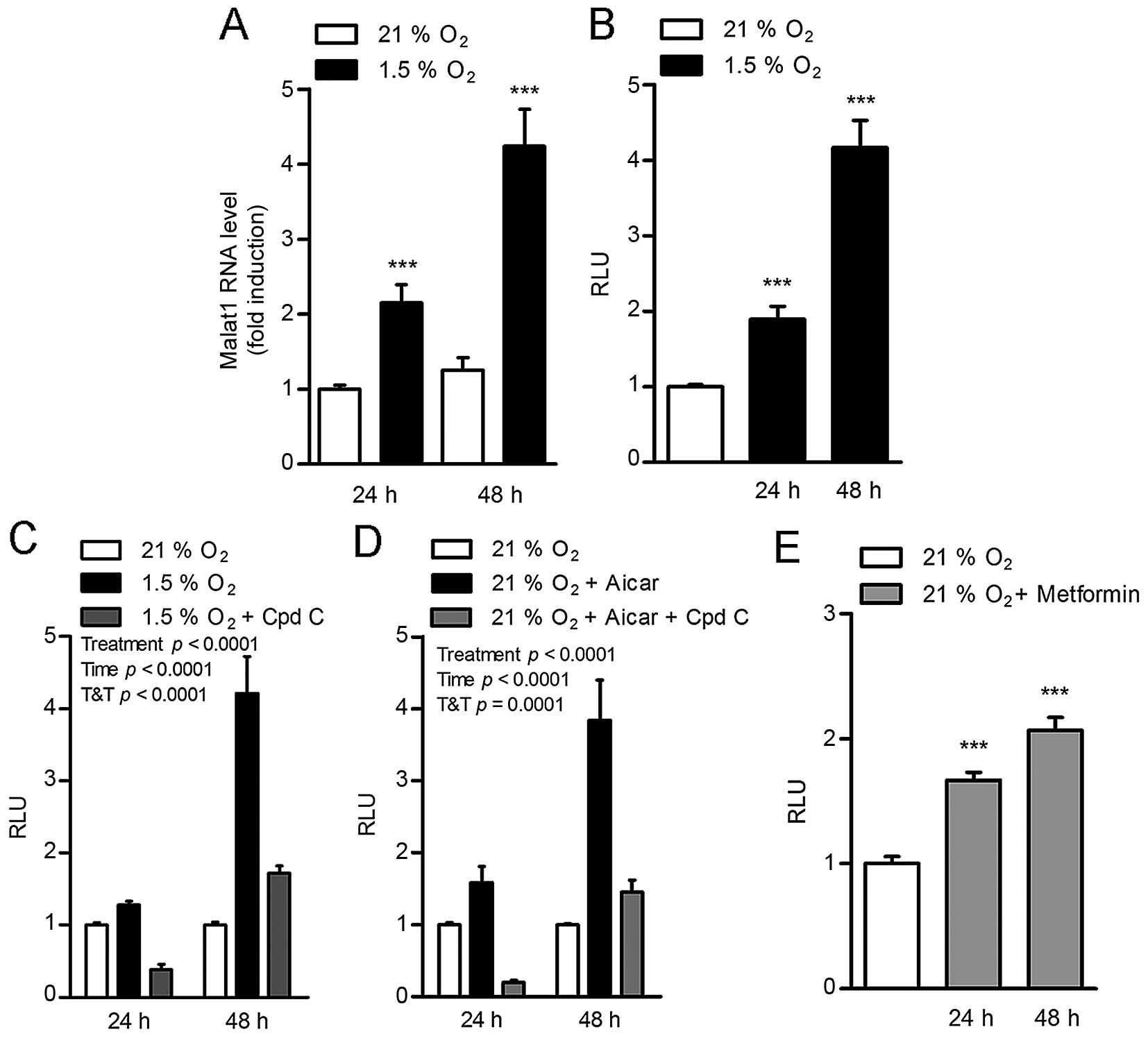

In adenocarcinoma HeLa cells, hypoxia (1.5%

O2) induced a time-dependent increase in Malat1 RNA

levels (Fig. 1A). To determine

that this effect was due to an impact on Malat1 gene transcription,

this experiment was repeated in HEK293T cells transfected with a

construct containing 5.6 kb of the human Malat1 promoter cloned

upstream of the luciferase gene. In this setting, hypoxia

stimulated Malat1 promoter transactivation to a similar

time-dependent extent, resulting in 2- and 4-fold increases after

24 and 48 h of incubation in low oxygen conditions, respectively

(Fig. 1B). This suggested a direct

impact of hypoxia on the Malat1 promoter.

Remarkably, the induction of the Malat1 promoter by

hypoxia was completely blocked by compound C (Fig. 1C), an ATP-competitive inhibitor of

AMPK (21), suggesting that AMPK

mediates the effect of 1.5% O2 conditions on Malat1

expression. Consistent with this concept, pharmacological

activation of AMPK with the 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide

ribonucleotide (AICAR) was sufficient to stimulate Malat1 promoter

transactivation in normal oxygen conditions (21% O2)

(Fig. 1D). This effect was

preventable by co-treatment with compound C (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the anti-diabetic

drug metformin, an indirect AMPK activator shown to lower

carcinogenesis (22), also induced

the activation of the Malat1 promoter, albeit to a lower extent

(Fig. 1E). Taken together, these

findings indicate that hypoxia stimulates Malat1 expression through

the activation of AMPK.

Inhibition of CaMKK blocks

hypoxia-induced Malat1 promoter transactivation

The activity of AMPK is mainly regulated by two

upstream kinases, namely the calcium-dependent kinase CaMKK and

LKB1, itself activated by EPAC (23,24).

In 21% O2 conditions, treatment of HEK293T cells with

the specific EPAC activator 8-CTP-2me-cAMP (25) did not result in the expected

increase in Malat1 promoter transactivation (Fig. 2A). In contrast, incubation with the

pharmacological CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 (26) completely prevented the induction of

the Malat1 promoter under hypoxia (Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that

hypoxia induces the CaMKK/AMPK cascade to stimulate Malat1

expression.

Hypoxia induces Malat1 via the induction

of HIF-1α

Analysis of protein extracts from cells incubated

under 21% and 1.5% O2 conditions indicated that hypoxia

induced the phosphorylation of AMPK at its Thr-172 residue within

60 min (Fig. 3A). In the same

conditions, an increase in HIF-1α was observed within 120 min under

hypoxia (Fig. 3A). This suggests

that the stimulation of HIF-1α protein levels occurs after

AMPK-activating events. Supporting this hypothesis, the

hypoxia-induced upregulation of HIF-1α levels was blocked in cells

incubated with the CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 (Fig. 3B). This further indicates that the

increase in HIF-1α levels is downstream of the CaMKK/AMPK

complex.

To investigate the possibility of a direct impact of

HIF-1α in the hypoxia-induced stimulation of Malat1 expression,

HEK293T cells containing the 5.6-kb human Malat1 promoter reporter

construct were treated with YC-1, a pharmacological inhibitor of

HIF-1α activity (27). Whereas

hypoxia increased Malat1 promoter transactivation in control cells

as expected, this effect was dose-dependently attenuated in cells

treated with YC-1 (Fig. 3C).

Consistent with this finding, transient overexpression of HIF-1α

under 21% O2 conditions was sufficient to transactivate

the Malat1 promoter (Fig. 3D).

This effect was completely abolished by co-treatment with YC-1

(Fig. 3D).

Discussion

The lncRNA Malat1 appears ubiquitously present in

cells during nonpathogenic conditions (8), however, several studies have reported

its high levels in many cancer types. Yet, the metabolic pathways

regulating its transcription in these conditions remain elusive.

This study focused on hypoxia, a powerful physiologic input in

solid tumors. This study strongly suggests that hypoxia triggers a

robust increase in Malat1 expression through the enhanced activity

of the CaMKK/AMPK/HIF-1α axis.

Although most studies on the stimulating impact of

Malat1 on cancer cell proliferation and migration have been

obtained in normoxic conditions (18), upregulation of Malat1 expression

during hypoxia has been recently observed in vitro and in

vivo (19). Our study

confirmed that hypoxia is an initial signal leading to increased

Malat1 expression level (Fig. 1).

Oxygen deprivation triggers several cellular processes required for

survival, including modulation of energy sensors such as AMPK

(3). Indeed, in hypoxic

environments, AMPK is phosphorylated (28), triggering the activation of its

downstream effector acetyl coenzyme A carboxylases 1 and 2

(ACC1/2). Such adaptive phenomenon is not observed in AMPK-null

mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) (28), highlighting the importance of AMPK

in the regulation of energy upon hypoxia. This study also found

that AMPK phosphorylation occurs early after oxygen deprivation,

and that this event is necessary for a full augmentation in Malat1

expression (Fig. 1). Thus, it is

likely that Malat1 overexpression is part of the global adaptive

response to low oxygen conditions.

The upstream mechanisms leading to hypoxia-driven

AMPK activation are unclear. In response to low energy status, AMPK

activation has been linked to phosphorylation of LKB1, a

serine/threonine kinase also associated with tumor suppression

(29). However, incubation of

cells with the LKB1 upstream kinase activator 8-CTP-2me-cAMP

suggests that LKB1 does not robustly modify Malat1 expression in

our model (Fig. 2A), which is

consistent with the absence of impact of PKA activators on the same

system (data not shown).

More recently, other studies indicated that CaMKK

may play an important role in hypoxia-induced AMPK stimulation

(30). Indeed, knockdown of LKB1

in MEFs cultured in hypoxic conditions had no impact on ACC1/2

phosphorylation, suggesting that LKB1 is not the upstream kinase

leading to AMPK activation under hypoxia (30). In contrast, knockdown of CaMKK in

the same system clearly diminished AMPK and ACC1/2 phosphorylation

status (30). This is in agreement

with the fact that hypoxia increases intracellular calcium

concentrations (31), which has

been recently shown to be regulated by the effects of

STIM1-mediated store-operated calcium entry (32). Our study is consistent with these

studies, since the specific CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 abolished the

activation of Malat1 under hypoxia (Fig. 2). The possible control of Malat1 by

STIM1 remains to be investigated.

Calcium plays major functions in the regulation of

gene expression. Notably, calcium chelation modulates HIF-1α

activity (33–35). Moreover, calcium entry rapidly

stimulates CaMKK-induced p300 phosphorylation, which stabilizes

HIF-1α (32,36). Our study also corroborates that

hypoxia-induced HIF-1α protein stabilization is under CaMKK

regulation, as it occurred after AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 3), and that cells treated with

STO-609 did not show high levels of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions

(Fig. 3). More importantly, this

study shows that Malat1 overexpression upon hypoxia is dependent of

HIF-1α, and that an increase in HIF-1α levels is sufficient to

stimulate Malat1 transcription to a similar extent as did hypoxia

(Fig. 3). Further supporting the

large contribution of HIF-1α in the increase in Malat1 in low

oxygen conditions, loss of HIF-1α activity by YC-1 treatment

completely blocked hypoxia-induced Malat1 transcription.

Interestingly, bioinformatics analysis indicated four putative

HIF-1α binding sites, corresponding to the consensus hypoxia

response element ([A/G]CGTG), within 5.6 kb of the human Malat1

promoter, at positions −2246, −1687, −1317, and −259 from the

initiation start of the Malat1 coding sequence. The relative

importance of each of these binding sites in the transactivation of

the Malat1 promoter by HIF-1α remains to be tested.

Interestingly, a recent study reported a possible

involvement of p53 as a transcriptional repressor of Malat1

expression in early stage of hematopoietic cell proliferation

(37). It is established that

oxygen deprivation modulates the levels and activity of p53, a

major transcription regulator of cellular fate under intensive

stress (38). Depending on oxygen

availability (39), it is thus

possible that p53 influenced the action of HIF-1α in this study,

since reciprocal transcriptional effects by HIF-1α and p53 have

been reported (1,40). At the molecular level, this is a

likely event as they share and compete for the nuclear cofactor

p300 (41).

In conclusion, this study was conducted to

understand the mechanisms regulating Malat1 expression levels upon

hypoxia, an important characteristic of cancer tissues. This study

indicates that the enhanced transcription of the Malat1 gene upon

low oxygen conditions is under the control of HIF-1α, itself

regulated by the activation of the CaMKK/AMPK complex, a master

regulator of cellular energy. Our results also support and extend

published literature that calcium influx is an early signal in the

adaptive response to hypoxic stress. Finally, since Malat1 induces

angiogenesis in cancer (18,42),

it would be of interest to determine its role in physiological

processes in which increased tissue mass is associated with high

demand for oxygen and energy substrates, such as exercise-induced

myogenesis, or cold-induced brown adipose tissue hyperplasia.

References

|

1

|

Harris AL: Hypoxia - a key regulatory

factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2:38–47. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson

CB: Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of

cell proliferation. Science. 324:1029–1033. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hardie DG and Carling D: The AMP-activated

protein kinase - fuel gauge of the mammalian cell? Eur J Biochem.

246:259–273. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Imamura K, Ogura T, Kishimoto A, Kaminishi

M and Esumi H: Cell cycle regulation via p53 phosphorylation by a

5′-AMP activated protein kinase activator,

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-D-ribofuranoside, in a human

hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

287:562–567. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Inoki K, Zhu T and Guan KL: TSC2 mediates

cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell.

115:577–590. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Maxwell PH, Dachs GU, Gleadle JM, Nicholls

LG, Harris AL, Stratford IJ, Hankinson O, Pugh CW and Ratcliffe PJ:

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 modulates gene expression in solid

tumors and influences both angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 94:8104–8109. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Salceda S and Caro J: Hypoxia-inducible

factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) protein is rapidly degraded by the

ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions. Its

stabilization by hypoxia depends on redox-induced changes. J Biol

Chem. 272:22642–22647. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Böing S,

Metzger R, Schneider PM, Tidow N, Brandt B, Buerger H, Bulk E, et

al: MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin beta4 predict

metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer.

Oncogene. 22:8031–8041. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lin R, Maeda S, Liu C, Karin M and

Edgington TS: A large noncoding RNA is a marker for murine

hepatocellular carcinomas and a spectrum of human carcinomas.

Oncogene. 26:851–858. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Eissmann M, Hsu

J, Kim Y, Hung G, Revenko A, Arun G, Stentrup M, Gross M, et al:

The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis

phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 73:1180–1189. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lai MC, Yang Z, Zhou L, Zhu QQ, Xie HY,

Zhang F, Wu LM, Chen LM and Zheng SS: Long non-coding RNA MALAT-1

overexpression predicts tumor recurrence of hepatocellular

carcinoma after liver transplantation. Med Oncol. 29:1810–1816.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Xu C, Yang M, Tian J, Wang X and Li Z:

MALAT-1: A long non-coding RNA and its important 3′ end functional

motif in colorectal cancer metastasis. Int J Oncol. 39:169–175.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ying L, Chen Q, Wang Y, Zhou Z, Huang Y

and Qiu F: Upregulated MALAT-1 contributes to bladder cancer cell

migration by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol

Biosyst. 8:2289–2294. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tano K, Mizuno R, Okada T, Rakwal R,

Shibato J, Masuo Y, Ijiri K and Akimitsu N: MALAT-1 enhances cell

motility of lung adenocarcinoma cells by influencing the expression

of motility-related genes. FEBS Lett. 584:4575–4580. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tripathi V, Shen Z, Chakraborty A, Giri S,

Freier SM, Wu X, Zhang Y, Gorospe M, Prasanth SG, Lal A, et al:

Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 controls cell cycle progression by

regulating the expression of oncogenic transcription factor B-MYB.

PLoS Genet. 9:e10033682013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tripathi V, Ellis JD, Shen Z, Song DY, Pan

Q, Watt AT, Freier SM, Bennett CF, Sharma A, Bubulya PA, et al: The

nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative

splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol

Cell. 39:925–938. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Eissmann M, Gutschner T, Hämmerle M,

Günther S, Caudron-Herger M, Gross M, Schirmacher P, Rippe K, Braun

T, Zörnig M, et al: Loss of the abundant nuclear non-coding RNA

MALAT1 is compatible with life and development. RNA Biol.

9:1076–1087. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Michalik KM, You X, Manavski Y,

Doddaballapur A, Zörnig M, Braun T, John D, Ponomareva Y, Chen W,

Uchida S, et al: Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates endothelial

cell function and vessel growth. Circ Res. 114:1389–1397. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lelli A, Nolan KA, Santambrogio S,

Gonçalves AF, Schönenberger MJ, Guinot A, Frew IJ, Marti HH,

Hoogewijs D and Wenger RH: Induction of long non coding RNA MALAT1

in hypoxic mice. Hypoxia (Auckl). 2015:45–52. 2015.

|

|

20

|

Miard S, Dombrowski L, Carter S, Boivin L

and Picard F: Aging alters PPARgamma in rodent and human adipose

tissue by modulating the balance in steroid receptor coactivator-1.

Aging Cell. 8:449–459. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X,

Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, et al: Role of

AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J

Clin Invest. 108:1167–1174. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM,

Alessi DR and Morris AD: Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in

diabetic patients. BMJ. 330:1304–1305. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fu D, Wakabayashi Y, Lippincott-Schwartz J

and Arias IM: Bile acid stimulates hepatocyte polarization through

a cAMP-Epac-MEK-LKB1-AMPK pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:1403–1408. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lo B, Strasser G, Sagolla M, Austin CD,

Junttila M and Mellman I: Lkb1 regulates organogenesis and early

oncogenesis along AMPK-dependent and -independent pathways. J Cell

Biol. 199:1117–1130. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Enserink JM, Christensen AE, de Rooij J,

van Triest M, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Døskeland SO, Blank JL and

Bos JL: A novel Epac-specific cAMP analogue demonstrates

independent regulation of Rap1 and ERK. Nat Cell Biol. 4:901–906.

2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tokumitsu H, Inuzuka H, Ishikawa Y, Ikeda

M, Saji I and Kobayashi R: STO-609, a specific inhibitor of the

Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem.

277:15813–15818. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yeo EJ, Chun YS, Cho YS, Kim J, Lee JC,

Kim MS and Park JW: YC-1: A potential anticancer drug targeting

hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 95:516–525. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Laderoute KR, Amin K, Calaoagan JM, Knapp

M, Le T, Orduna J, Foretz M and Viollet B: 5′-AMP-activated protein

kinase (AMPK) is induced by low-oxygen and glucose deprivation

conditions found in solid-tumor microenvironments. Mol Cell Biol.

26:5336–5347. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley

RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA and Cantley LC: The tumor suppressor

LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates

apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

101:3329–3335. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mungai PT, Waypa GB, Jairaman A, Prakriya

M, Dokic D, Ball MK and Schumacker PT: Hypoxia triggers AMPK

activation through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of

calcium release-activated calcium channels. Mol Cell Biol.

31:3531–3545. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Arnould T, Michiels C, Alexandre I and

Remacle J: Effect of hypoxia upon intracellular calcium

concentration of human endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol.

152:215–221. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li Y, Guo B, Xie Q, Ye D, Zhang D, Zhu Y,

Chen H and Zhu B: STIM1 mediates hypoxia-driven

hepatocarcinogenesis via interaction with HIF-1. Cell Rep.

12:388–395. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mottet D, Michel G, Renard P, Ninane N,

Raes M and Michiels C: ERK and calcium in activation of HIF-1. Ann

NY Acad Sci. 973:448–453. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mottet D, Michel G, Renard P, Ninane N,

Raes M and Michiels C: Role of ERK and calcium in the

hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1. J Cell Physiol. 194:30–44.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Petrat F, Doege

K, Trinidad B, Freitag P, Metzen E, de Groot H and Fandrey J:

Chelation of cellular calcium modulates hypoxia-inducible gene

expression through activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J

Biol Chem. 279:44976–44986. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hui AS, Bauer AL, Striet JB, Schnell PO

and Czyzyk-Krzeska MF: Calcium signaling stimulates translation of

HIF-alpha during hypoxia. FASEB J. 20:466–475. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ma XY, Wang JH, Wang JL, Ma CX, Wang XC

and Liu FS: Malat1 as an evolutionarily conserved lncRNA, plays a

positive role in regulating proliferation and maintaining

undifferentiated status of early-stage hematopoietic cells. BMC

Genomics. 16:6762015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Koumenis C, Alarcon R, Hammond E, Sutphin

P, Hoffman W, Murphy M, Derr J, Taya Y, Lowe SW, Kastan M, et al:

Regulation of p53 by hypoxia: Dissociation of transcriptional

repression and apoptosis from p53-dependent transactivation. Mol

Cell Biol. 21:1297–1310. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhou CH, Zhang XP, Liu F and Wang W:

Modeling the interplay between the HIF-1 and p53 pathways in

hypoxia. Sci Rep. 5:138342015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sermeus A and Michiels C: Reciprocal

influence of the p53 and the hypoxic pathways. Cell Death Dis.

2:e1642011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schmid T, Zhou J, Köhl R and Brüne B: p300

relieves p53-evoked transcriptional repression of hypoxia-inducible

factor-1 (HIF-1). Biochem J. 380:289–295. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Tee AE, Liu B, Song R, Li J, Pasquier E,

Cheung BB, Jiang C, Marshall GM, Haber M, Norris MD, et al: The

long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes tumor-driven angiogenesis by

up-regulating pro-angiogenic gene expression. Oncotarget.

7:8663–8675. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|