Introduction

Liposarcoma, a malignant tumor derives from

mesodermal tissues, represents ~20% of all sarcomas. Paratesticular

liposarcoma (PLS) is a rare condition. To the best of our

knowledge, about 200 cases of PLS have been reported to date

(1). Giant PLS is more rare with

only a few cases having been reported (2–6). Due to

the rarity of the disease, there is no standardized guideline as

regards its incidence, diagnosis, recurrence and treatment

(7,8). In this study, we present a case of a

giant dedifferentiated PLS of the right testis with magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) measuring 7.8×5.8×10.4 cm and focus on the

discussion about the clinical characteristics, diagnosis and

treatment of this disease. Due to the giant size of this PLS, we

report this case for the characteristics, diagnosis and treatment

of the similar cases. The study was supported by the Ethics

Committee of Peking University Shenzhen Hospital (Shenzhen, China)

and written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the

publication of the case details.

Case report

In July 2017, a 51-year-old man, with a complaint of

swelling of the right scrotum for 2 months, was admitted to the

Department of Urology of our hospital. He presented with a painless

and slow-growing fixed mass in the right scrotum without

conspicuous promoting or alleviating factors. There are no other

signs or symptoms. A rigid mass in the right scrotum, about 8 cm in

maximum diameter, was the only positive finding of physical

examinations. There are no specific abnormalities in the laboratory

and imaging examinations (hemogram, urinalysis, stool routine, ESR,

β-human chorionic gonadotropin, a-fetoprotein, mycobacterium

tuberculosis antibody Ig-G, liver and kidney function tests and

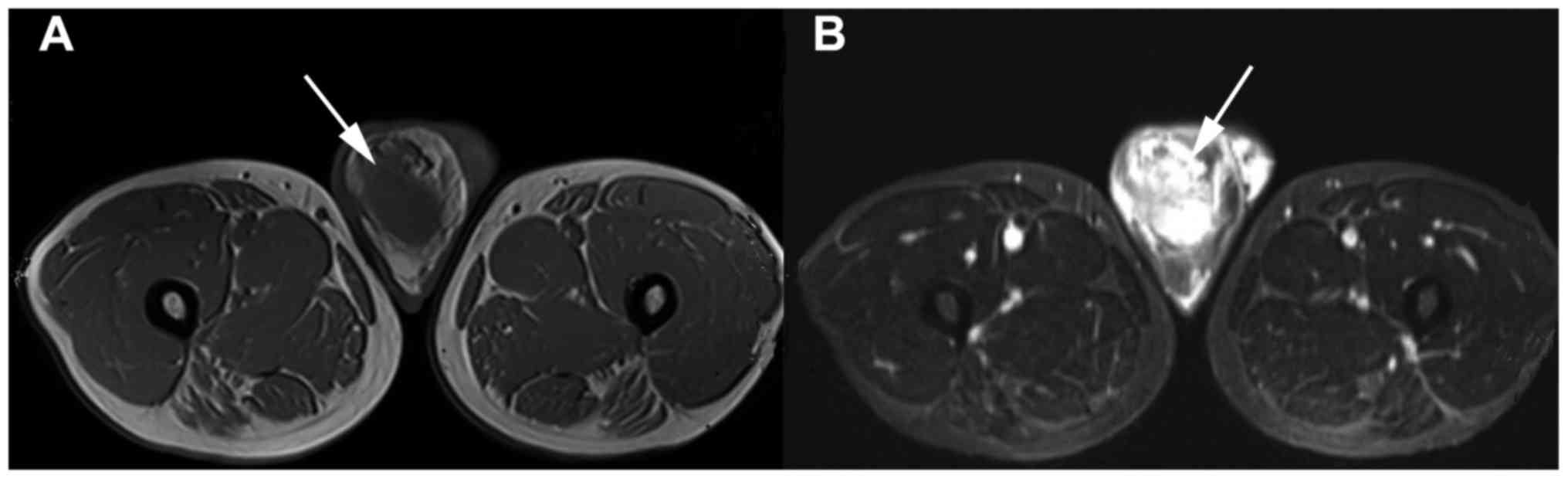

chest X-ray). However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

demonstrated a 7.8×5.8×10.4 cmnonhomogeneous space-occupying lesion

of the right testis (Fig. 1), which

was considered as spermatocytoma at first.

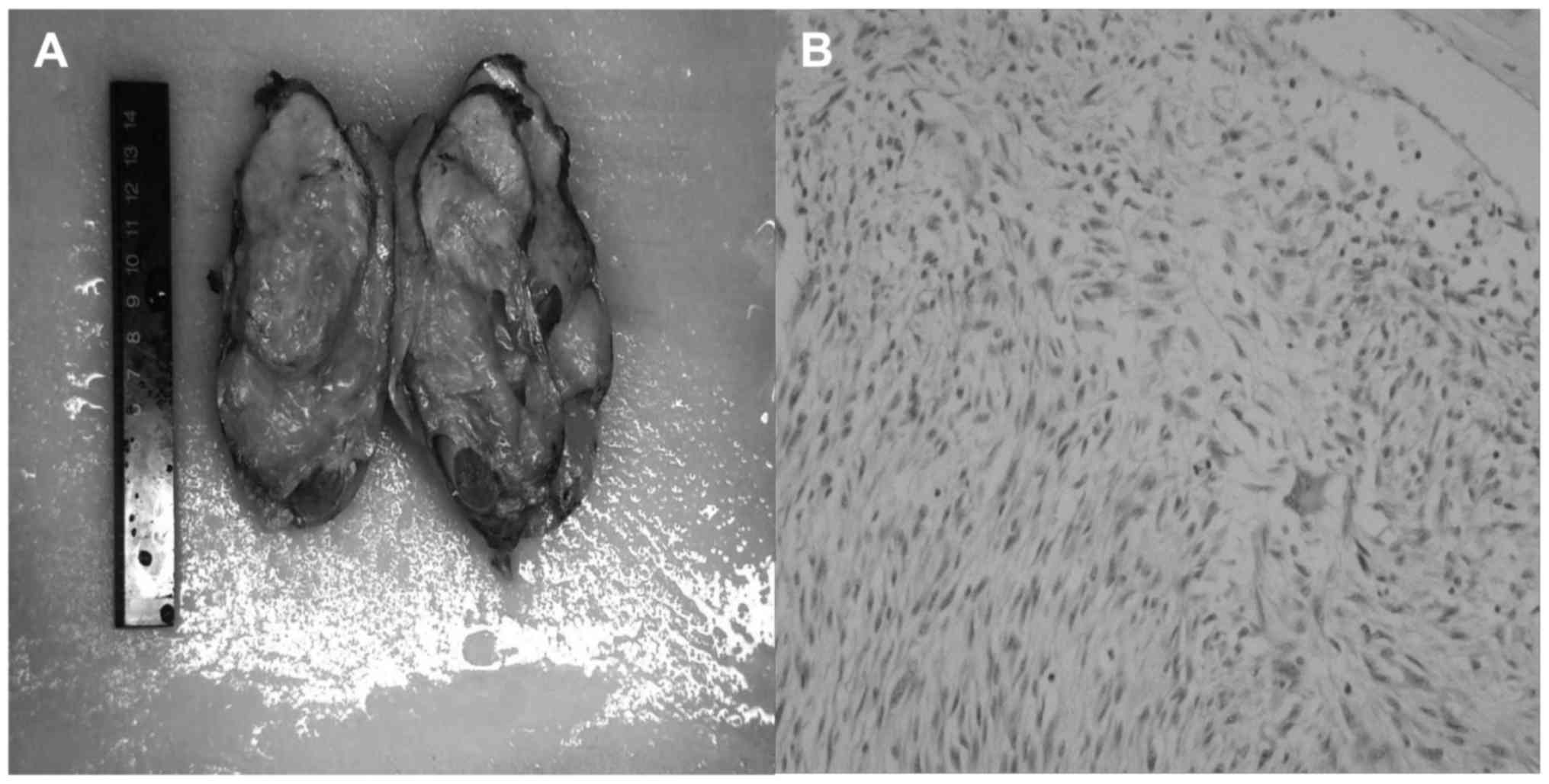

Following the doctors' recommendation, the patient

underwent a radical resection of the tumor combined with a right

orchiectomy. An enlarged rigid testicle measuring 13×8×6 cm was

removed out of the right scrotum. There is no evident inflammatory

adhesion to the surrounding organs. On gross pathological

examination, the resected specimen was an enlarged mass with a cut

surface having yellowish lipoma-like texture. Final

histopathological examination confirmed that it was a giant

dedifferentiated liposarcoma (Fig.

2). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that CD34(−); SMA(+);

S-100(−)(most of cells); ALK(−) and supported this diagnosis. At

5-month follow-up, there is no evidence of local recurrence or

distant metastasis.

Discussion

Liposarcoma, soft-tissue malignancy derived

embryologically from mesodermal tissue, was first reported by

Lesauvage in 1845 (9). They usually

exist in the lower extremities and retroperitoneum (10,11).

There are four histological subtypes in liposarcoma, which include

well differentiated, dedifferentiated, myxoid and pleomorphic

(12). PLS are rare neoplasm which

compose approximately 12% of all liposarcomas and they originate in

spermatic cord mostly followed by testicular tunics and epididymis

(13). When the diameter of

testicular tumor reaches more than 10 cm, such size will be called

‘giant’ (5). As far as we know, 200

or so cases of PLS have been reported up to date (14), and giant PLS are more rare with only

a few cases having been reported (2–6). The

incidence of PLS has a regional difference with the highest

incidence being in Japan (7). The

tumor attacked adult patients aged 50 to 60 years more frequently

(15), though it occurred in

patients with a range of 16 to 90 years of age on the basis of the

current literature (16,17). PLS mostly present as a painless,

slow-growing inguinal or inguinoscrotal mass and sometimes combine

with a sensation of heaviness (9,14,16) and

the occurrence of wrong diagnosis like scrotal lipoma, inguinal

hernia and epididymitis before surgical intervention attribute to

this clinical presentation (12,15).

Most PLS are primary, but some can be metastasis from liposarcoma

at other sites, such as thigh or the fatty tissue surrounding the

testicle (18,19). Because of the insufficient number of

literature on patients with PLS, no reliable standardized diagnosis

and treatment guidelines have been made (14).

Ultrasonography (US), Computerized Tomography (CT)

and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are documented in the

diagnosis of PLS (20,21). On US examination, PLS are identified

as solid, heterogeneous solid, hypoechoic lesions, sometimes

accompanied by colliquation if there is necrosis. However, US

cannot always distinguish PLS from lipomas if the tumor is small or

it is a well-differentiated PLS with homogenous fatty pattern,

which makes PLS similar to lipoma (10,14,22).

Compared to subcutaneous fatty tissue, CT usually demonstrates the

tumor area with lower density. It may be helpful to establish tumor

location, tissue characteristics, staging and follow-up (8,16,23).

MRI, the golden standard in staging soft tissue tumors, not only

provides clear information on the tumor foci but also characterizes

and delineates the degree of local tumor extension (9,14,20).

Diagnosis of PLS mainly depends on histopathology,

immunohistochemistry and cytomorphological features. A Critical

histopathological analysis of dedifferentiated liposarcomas

revealed that CD34 was negative in 9/11 cases; negative rate of

s-100 was 92% (23/25); MDM2 was diffusely positive in

well-differentiated areas and focally in dedifferentiated areas in

the tumor with homologous dedifferentiation; SMA was positive in

2/8 tumors (24). Andrei et

al proved that MDM2 and CDK4 were significative markers for

confirming the diagnosis of well-differentiated liposarcoma

(23). Histologically,

differentiated sarcoma can be subdivided into five main subtype:

Resembling pleomorphic malignant fibrous histiocytoma,

fibrosarcoma, rhabdmyofibrosarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma and

hemangiopericytoma (25,26). A total of 76% of dedifferentiated

liposarcomas was high-grade (24).

Multimodality therapy was suggested by many

researchers (27–29). There is a general consensus that

radical orchiectomy with wide local excision and high ligation of

the spermatic cord are the current standard treatment strategies

due to frequent recurrence that associated with incomplete excision

(7–9,20).

Because the clinical presentation of PLS is similar to scrotal

lipoma or groin hernia, Immediate radical procedure should be

performed to avoid the high risk of local recurrence and

involvement of worsening prognosis, when a suspicious PLS is

diagnosed. It is important to prohibit spillage of malignant cells

and acquire a more safe edge during the operation. A clinical

research showed that the 3-year local-recurrence-free survival was

100% for negative margins compared with 29% for positive margins

(30). Retroperitoneal lymph node

dissection is not recommended except for metastasis (7). It has been reported that occult local

residual lesions were found at least a third of patients after

operation (1), thus not only in

dedifferentiated PLS, considered with a high rate of recurrence and

metastasis, but also in other subtypes of PLS, adjuvant radiation

is quite needed (9,14,31).

Cerda et al (32)reported

that five patients with spermatic cord sarcoma given adjuvant

radiotherapy with a total dose of 54 Gy/27 or 30 fractions were

found no recurrence in median 18 months of follow-up (range 6–28

months). However, whether radiotherapy should be used as

postoperative routine therapy remains to be discussed because

recurrent tumor after radiotherapy may be more aggressive (10). Some suggested that radiotherapy

should be used for local control (8,10,14,30).

There are no large studies with respect to the results of

chemotherapy. A meta-analysis of 14 randomized clinical trials

discovered that the improvement of recurrence and recurrence-free

survival were attributed to chemotherapy (14,33).

Some studies reported that we should attach importance to

chemotherapy for high grade LPS (1).

Research report on prognosis of PLS is quite limited

until now. A recent study local-recurrence-free survival was 76% at

3 years and 67% at 5 years (30).

Another study about PLS revealed the 5-year survival rate was 75%

and recurrence rate was 50–70% of all cases (14). Prognosis and overall survival rate

vary in accordance with some risk factors, which include tumor

grade, size, depth of invasion and histopathological classification

(most important). The dedifferentiated types have a worse

prognosis, but local recurrence rate will be smaller (14,34).

In conclusion, PLS represent a rarity of the tumor,

characterized with slow growth, which are often misdiagnosed

preoperatively. US, CT and MRI can redound to diagnose and

differential diagnose, but the final diagnosis of PLS depends on

histopathology and immunohistochemistry. When diagnosed or highly

suspected preoperatively, radical orchiectomy with wide local

excision and high ligation is the best treatment strategy and

multimodality therapy is suggested. Long-term follow-up is

recommended due to the risk of local recurrence and distant

metastasis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 8110122), Science and

Technology Development Fund Project of Shenzhen (nos.

JCYJ20150403091443329 and JCYJ20170307111334308), the fund of

‘San-ming’ Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (no. SZSM201612066) and

the fund of Guangdong Key Medical Subject.

References

|

1

|

Chiodini S, Luciani LG, Cai T, Molinari A,

Morelli L, Cantaloni C, Barbareschi M and Malossini G: Unusual case

of locally advanced and metastatic paratesticular liposarcoma: A

case report and review of the literature. Arch Ital Urol Androl.

87:87–89. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Sopena-Sutil R, Silan F, Butron-Vila MT,

Guerrero-Ramos F, Lagaron-Comba E and Passas-Martinez J:

Multidisciplinary approach to giant paratesticular liposarcoma. Can

Urol Assoc J. 10:E316–E319. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fernandez F and Garcia HA: Giant

dedifferenciated liposarcoma of the spermatic cord. Arch Esp Urol.

62:751–755. 2009.(In Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cariati A, Brignole E, Tonelli E and

Filippi M: Giant paratesticular undifferentiated liposarcoma that

developed in a long-standing inguinal hernia. Eur J Surg.

168:511–512. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kin T, Kitsukawa S, Shishido T, Maeda Y,

Izutani T, Yonese J and Fukui I: Two cases of giant testicular

tumor with widespread extension to the spermatic cord: Usefulness

of upfront chemotherapy. Hinyokika Kiyo. 45:191–194. 1999.(In

Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Martin C, Olivier CM, Rengifo D, Hernandez

Lao A, Ondina LM and Carballido J: Giant liposarcoma of the

spermatic cord. Actas Urol Esp. 17:361–365. 1993.(In Spanish).

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li F, Tian R, Yin C, Dai X, Wang H, Xu N

and Guo K: Liposarcoma of the spermatic cord mimicking a left

inguinal hernia: A case report and literature review. World J Surg

Oncol. 11:182013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Alyousef H, Osman EM and Gomha MA:

Paratesticular liposarcoma: A case report and review of the

literature. Case Rep Urol. 2013:8062892013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Vukmirović F, Zejnilović N and Ivović J:

Liposarcoma of the paratesticular tissue and spermatic cord: A case

report. Vojnosanit Pregl. 70:693–696. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Raza M, Vinay HG, Ali M and Siddesh G:

Bilateral paratesticular liposarcoma-a rare case report. J Surg

Tech Case Rep. 6:15–17. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Vinayagam K, Hosamath V, Honnappa S and

Rau AR: Paratesticular liposarcoma-masquerading as a testicular

tumour. J Clin Diagn Res. 8:165–166. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

García Morúa A, Lozano Salinas JF, Valdés

Sepúlveda F, Zapata H and Gómez Guerra LS: Liposarcoma of the

espermatic cord: Our experience and review of the literature. Actas

Urol Esp. 33:811–815. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Noguchi H, Naomoto Y, Haisa M, Yamatsuji

T, Shigemitsu K, Uetsuka H, Hamasaki S and Tanaka N:

Retroperitoneal liposarcoma presenting a indirect inguinal hernia.

Acta Med Okayama. 55:51–54. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Schoonjans C, Servaes D and Bronckaers M:

Liposarcoma scroti: A rare paratesticular tumor. Acta Chir Belg.

116:122–125. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fitzgerald S and Maclennan GT:

Paratesticular liposarcoma. J Urol. 181:331–332. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gabriele R, Ferrara G, Tarallo MR,

Giordano A, De Gori A, Izzo L and Conte M: Recurrence of

paratesticular liposarcoma: A case report and review of the

literature. World J Surg Oncol. 12:2762014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bostwick DG: Spermatic cord and testicular

adnexa. 1997.

|

|

18

|

Fahsi O, Kallat A, Ouazize H, Dergamoun H,

Sayegh HE, Iken A, Benslimane L and Nouini Y: Metastatic

paratesticular liposarcoma. Pan Afr Med J. 27:1012017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Thinyu S and Muttarak M: Role of

ultrasonography in diagnosis of scrotal disorders: A review of 110

cases. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 5:e22009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Pergel A, Yucel AF, Aydin I, Sahin DA,

Gucer H and Kocakusak A: Paratesticular liposarcoma: A radiologic

pathologic correlation. J Clin Imaging Sci. 1:572011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yoshino T, Yoneda K and Shirane T: First

report of liposarcoma of the spermatic cord after radical

prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 29:677–680.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Montgomery E and Fisher C: Paratesticular

liposarcoma: A clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 27:40–47.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pănuş A, Meşină C, Pleşea IE, Drăgoescu

PO, Turcitu N, Maria C and Tomescu PI: Paratesticular liposarcoma

of the spermatic cord: A case report and review of the literature.

Rom J Morphol Embryol. 56:1153–1157. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rekhi B, Navale P and Jambhekar NA:

Critical histopathological analysis of 25 dedifferentiated

liposarcomas, including uncommon variants, reviewed at a Tertiary

Cancer Referral Center. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 55:294–302.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

McCormick D, Mentzel T, Beham A and

Fletcher CD: Dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Clinicopathologic

analysis of 32 cases suggesting a better prognostic subgroup among

pleomorphic sarcomas. Am J Sur Pathol. 18:1213–1223. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Coindre JM, Pedeutour F and Aurias A:

Well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas. Virchows

Arch. 456:167–179. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Brennan MF, Casper ES, Harrison LB, Shiu

MH, Gaynor J and Hajdu SI: The role of multimodality therapy in

soft-tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg. 214:328–338. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kanso C, Roussel H, Zerbib M, Flam T,

Debré B and Vieillefond A: Spermatic cord sarcoma in adults:

Diagnosis and management. Prog Urol. 21:53–58. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sherman KL, Wayne JD, Chung J, Agulnik M,

Attar S, Hayes JP, Laskin WB, Peabody TD, Bentrem DJ, Pollock RE

and Bilimoria KY: Assessment of multimodality therapy use for

extremity sarcoma in the United States. J Surg Oncol. 109:395–404.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Khandekar MJ, Raut CP, Hornick JL, Wang Q,

Alexander BM and Baldini EH: Paratesticular liposarcoma: Unusual

patterns of recurrence and importance of margins. Ann Surg Oncol.

20:2148–2155. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Song CH, Chai FY, Saukani MF, Singh H and

Jiffre D: Management and prevention of recurrent paratesticular

liposarcoma. Malays J Med Sci. 20:95–97. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cerda T, Martin É, Truc G, Créhange G and

Maingon P: Safety and efficacy of intensity-modulated radiotherapy

in the management of spermatic cord sarcoma. Cancer Radiother.

21:16–20. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gago Juan A, Luján Galán M, Bustamante

Alarma S, Fernández Lobato R, Zárate Rodríguez E, Martín Osés E and

Berenguer Sánchez A: A paratesticular myxoid liposarcoma as a

simulator of a hernial process. A case report. Arch Esp Urol.

50:921–923. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Stranne J, Hugosson J and Lodding P:

Post-radical retropubic prostatectomy inguinal hernia: An analysis

of risk factors with special reference to preoperative inguinal

hernia morbidity and pelvic lymph node dissection. J Urol.

176:2072–2076. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|