Introduction

The expression of insulin genes in pancreatic islet

cells is affected by plasma glucose or intracellular cAMP (1,2).

cAMP response element binding protein (CREBP) stimulates the

transcription of insulin genes by binding to CREs in the promoter

region (3,4). Among the CREB family members, CRE

modulator (CREM) is a unique gene that encodes either

transcriptional activators or repressors based on alternative

splicing (5). In particular,

inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) has an important role as a

dominant-negative regulator of CREB and CREM activity, and consists

of DNA binding and leucine zipper domains, while also lacking an

N-terminal transactivation domain. As a strong repressor of

cAMP-induced gene expression, the ICER acts as an endogenous

inhibitor competing with CREB on the CRE sequence, and then ICER Iγ

induces the return of cAMP signaling to the basal state (6). Of note, prolonged expression of ICER

Iγ results in the development of pathological conditions.

Previously, it was reported that the overexpression of ICER Iγ is

associated with an increased incidence of diabetes and decreased

β-cell numbers in transgenic mice (7,8).

When using constructs with a constitutively active

promoter, the unregulated expression of a target gene often

produces unexpected results. To avoid these limitations, a

conditional transgenic technique was adopted, the tetracycline

(tet)-on system. This system enables both temporal and spatial

regulation of transgene expression, and requires a responder

construct and activator construct in a single cell (9). Transcriptional activator protein

(tTA; a transactivator) consists of a modified bacterial tet

repressor (TetR) fused to three minimal activation domains of the

herpes simplex virus transcription activator (VP16). Expression of

this construct is controlled by tetracycline or its analog,

doxycycline (dox) (10). In the

presence of dox, a conformational change in tTA allows the

activator to bind to the tTA-response element (TRE) promoter of a

responder construct, and induces transcription of the target gene

and a green fluorescent protein reporter gene downstream of the TRE

promoter. The TRE promoter consists of seven repeats of a 19-bp tet

operator sequence located upstream of a minimal cytomegalovirus

(CMV) promoter in which the binding sites for endogenous mammalian

transcription factors have been eliminated (11).

In the present study, a pancreas-specific,

dox-inducible ICER Iγ expression vector was constructed, where the

CMV promoter was exchanged for the human insulin promoter in the

activator construct. Additionally, this construct contained a

unitary system combined with an activator cassette and responder

cassette. Although in vivo experiments designed to study

diabetes have been conducted in rodents and other animals (12,13),

the phenotypic hallmarks of diabetes mellitus in rodent models are

not sufficient to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying the

development of diabetes in humans. Therefore, porcine transgenic

fibroblasts were also established, that were genetically modified

to evoke type 1 diabetes mellitus-like symptoms in a porcine

model.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Chungbuk National University (Cheongju, Korea). The porcine

fibroblasts were obtained from miniature pig fetuses (Yucatan pigs;

Optifarm Solution Inc., Gyeonggi-do, Korea) on the thirtieth day of

pregnancy and the cells were routinely maintained in Dulbecco’s

Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 25 mM glucose,

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; WelGENE, Inc.,

Daejeon, South Korea), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml

streptomycin. The mouse β-cell line, MIN6 (American Type Culture

Collection, Manassas, VA, USA), was cultured in DMEM containing 25

mM glucose, supplemented with 15% FBS, 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol

(Gibco, Grand island, NY, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml

streptomycin. All cells were grown in a humidified 5%

CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Unless otherwise indicated, all

cell culture materials were obtained from Invitrogen Life

Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR

Genomic DNA from the cells was isolated with a

G-DEX™ IIc Genomic DNA Extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc.,

Seoul, South Korea). Genomic DNA (0.1 μg) was amplified in a 20-μl

PCR reaction containing 1 U i-Start Taq polymerase (iNtRON

Biotechnology, Inc.), 2 mM dNTPs (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan)

and 10 pmol of each specific primer. The details of all primers are

described in Table I. The PCR

reactions were denatured at 94°C for 30 sec, annealed at 62°C for

30 sec and extended at 72°C for 1–2 min. The PCR products were

subjected to cloning processes and/or separated on a 1% agarose

gel, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV

illumination. The image was scanned using GelDoc EQ (Bio-Rad,

Hercules, CA, USA).

| Table IPrimer sequences. |

Table I

Primer sequences.

| Primer name | Restriction

enzyme | Direction | Sequences (5′ to

3′) |

|---|

| Human insulin

promoter (−1,432) | SpeI | Forward | ACT AGT TAC CCC AGG

GGC TCA GCC CAG ATG |

| Human insulin

promoter (+1) | EcoRI | Reverse | GAA TTC GGC CAG CAG

CGC CAG CAG G |

| ICER Iγ cDNA | MluI | Forward | ACG CGT ATG GCT GTA

ACT GGA GAT GA |

| ICER Iγ cDNA | BamHI | Reverse | GGA TCC CTA ATC TGT

TTT AGG AGA GCA AAT G |

| Tet-response

cassette | Bst1107I | Forward | GTA TAC CGA GGC CCT

TTC GTC TTC AAG AAT TC |

| Tet-response

cassette | SpeI | Reverse | ACT AGT GCC GCA GAC

ATG ATA AGA TAC ATT GA |

| Confirming primer

a | | Forward | GTG CTG ACG ACC AAG

GAG AT |

| Confirming primer

a′ | | Reverse | TTT CAG AAG TGG GGG

CAT AG |

| Confirming primer

b | | Forward | GAG GAT GGA GCA GTT

TGC AT |

| Confirming primer

b′ | | Reverse | GCA TTC CAC CAC TGC

TCC CA |

| ICER Iγ | | Forward | ATG GCT GTA ACT GGA

GAT GA |

| ICER Iγ | | Reverse | CTA ATC TGT TTT AGG

AGA GCA AAT G |

| Insulin-1 | | Forward | CCC TGT TGG TGC ACT

TCC TA |

| Insulin-1 | | Reverse | CAC TTG TGG GTC CTC

CAC TT |

| Mouse β-actin | | Forward | ACA GGC ATT GTG ATG

GAC TC |

| Mouse β-actin | | Reverse | ATT TCC CTC TCA GCT

GTG GT |

Vector construction

All restriction enzymes were obtained from Takara

Bio, Inc. The human insulin promoter region (from nucleotides (nt)

−1,431 to +1 nt; +1 = the transcriptional start site) demonstrated

the highest transcriptional activity in a previous study (14) and were prepared by long-range PCR

using human genomic DNA (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA,

USA) as the template, and specific primers containing restriction

enzyme sites (SpeI at the 5′ end or EcoRI at the 3′ end). Amplified

fragments were digested with SpeI and EcoRI and replaced with the

CMV promoter of the transcriptional activator construct,

pCMV-Tet3G, purchased from Clontech Laboratories. The ICER Iγ cDNA

was prepared by PCR using genomic DNA from pig pancreas as the

template and was inserted into pTRE3G-ZsGreen1 which contains green

fluorescence protein, ZsGreen1 (Clontech Laboratories) through MluI

at the 5′ end or BamHI at the 3′ end. Using the PCR method, the

ICER Iγ-expressing tTA-response region obtained from recombinant

pTRE3G-ZsGreen1-pig ICER Iγ construct was digested with Bst1107I or

SpeI and combined with the recombinant pHINSP-Tet3G vector

controlled by the human insulin promoter.

Establishment of transgenic cell

lines

The fibroblasts were transfected with the linearized

targeting vector using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen,

Carlsbad, CA, USA). Following 24 h of transfection, the medium was

replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 250 μg/ml G-418

(Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for four weeks. The

antibiotic-resistant cells were further selected, subjected to

PCR-based genotyping and stored until required for somatic cell

nuclear transfer.

Transient transfection and dox

treatment

Transient transfection was performed using

Lipofectamine™ 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Briefly, 3×105 cells were seeded in 6-well tissue

culture plates one day prior to transfection. In total, 4 μg of the

recombinant constructs per well was transfected into the cells

under serum-free DMEM. Following incubation for 4 h, the medium was

replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin. A total of 20 h later, various concentrations

of dox were treated in transiently transfected cells for an

additional 24 h.

RNA preparation and semi-quantitative

(q)PCR

Total RNA from MIN6 cells was extracted using TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the total RNA was

determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. First-strand cDNA

was prepared by subjecting total RNA (1 μg) to reverse

transcription using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse

transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and random primers

(9-mers; Takara Bio, Inc.). To determine the optimal conditions for

logarithmic phase PCR amplification for target cDNA, aliquots of

total cDNA (1 μg) were amplified using different numbers of cycles.

The mouse β-actin gene was amplified as the internal control to

rule out the possibility of RNA degradation and to control for

variations in mRNA concentrations. A linear correlation between PCR

product band visibility and the number of amplification cycles was

observed for the target mRNA. The mouse β-actin and target genes

were quantified using 28 and 30 cycles, respectively. The PCR

reactions were denatured at 94°C for 30 sec, annealed at 58°C for

30 sec and extended at 72°C for 30 sec. The PCR products were on a

2.3% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed

under UV illumination. The image was scanned using GelDoc EQ

(Bio-Rad).

Western blot analysis

Lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH

7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium

deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM PMSF) and protease inhibitor

cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). Protein content was determined using

the Pierce BCA Micro Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA, USA). Total proteins obtained by centrifugation

(13,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C) were denatured at 95°C for 5 min. A

total of 20–50 μg of protein were size-separated by electrophoresis

on 13% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electrophoretically transferred

to a nitrocellulose membrane. Non-specific binding was blocked with

TBST (20 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween-20)

containing 5% non-fat milk for 2 h at room temperature (RT). The

membrane was probed with the following primary antibodies for 2 h

at RT: rabbit polyclonal antibody to Insulin (H-86, sc-9168),

diluted 1:1,000; rabbit polyclonal antibody to CREM (X-12, sc-440),

diluted 1:1,000 and rabbit polyclonal antibody to β-actin (N-21,

sc-130656), diluted 1:1,000. All antibodies were purchased from

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The membrane

was subsequently exposed to a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution in TBST) for 1 h at RT.

Results

Establishment of a unitary tet-on ICER Iγ

expression vector

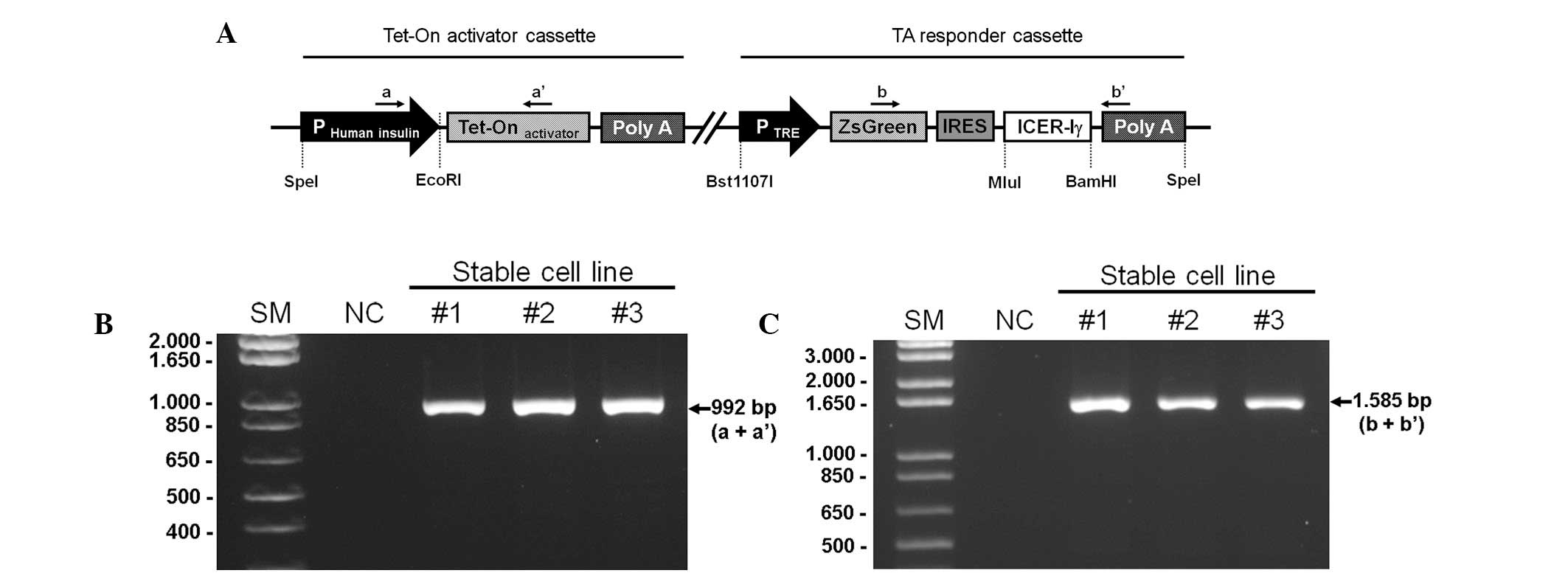

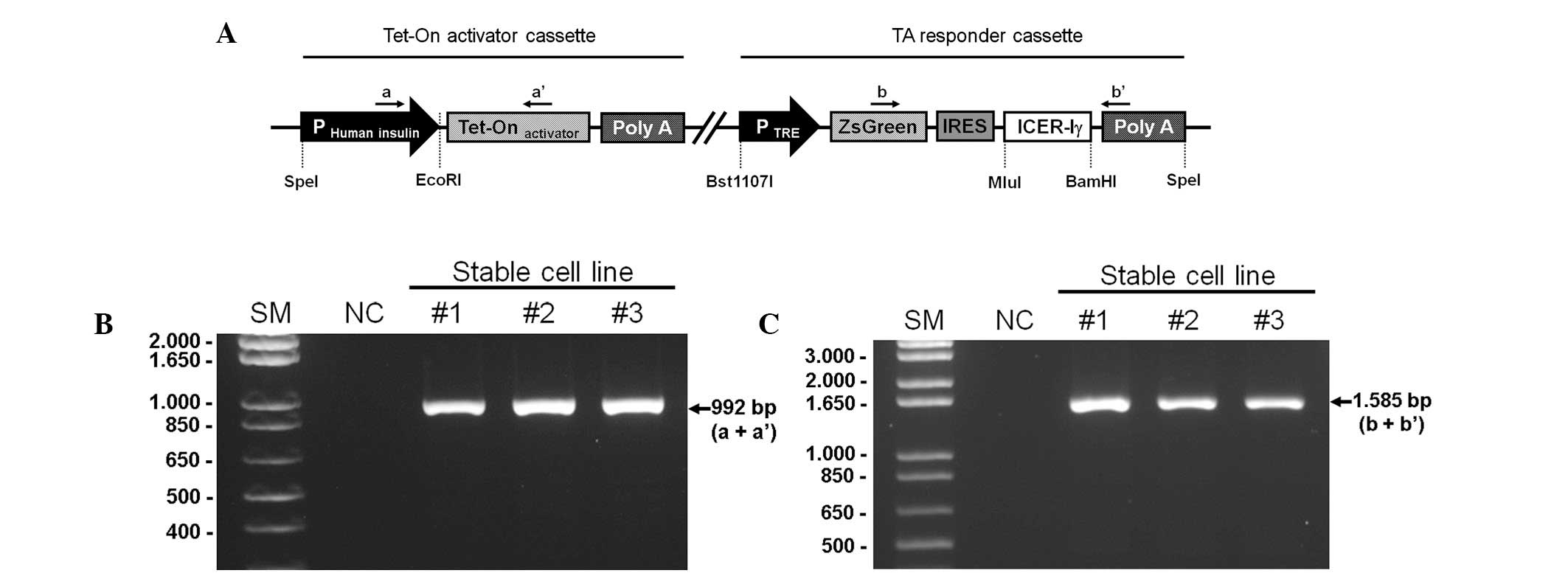

The unitary tet-on system was composed of an

activator cassette and responder cassette (Fig. 1A). The activator cassette had a tTA

under the control of the human insulin promoter (−1,432 to +1 nt)

which is associated with maximum promoter activity in mouse MIN6

β-cells line according to our previous study (14). The responder cassette contained the

porcine ICER Iγ target gene and cDNA encoding ZsGreen1 green

fluorescence protein. The expression of both genes was controlled

by a TRE promoter. tTA was specifically transcribed in pancreas

cells under the control of the human insulin promoter, underwent a

conformational change induced by the administration of dox and then

bound to the TRE promoter of the responder cassette. Finally, the

key gene downstream of the TRE promoter, ICER Iγ, was specifically

transcribed in the pancreas cells. Additionally, expression of the

green fluorescence marker, ZsGreen1, was observed.

| Figure 1Schematic structure of the targeting

vector and PCR-based confirmation of transgenic fibroblasts. (A)

The unitary tet-on system was composed of two parts in a vector; an

activator cassette and a responder cassette. The activator cassette

had tTA under the control of the human insulin promoter (−1,432 to

+1 nt). The responder cassette contained the target gene, porcine

ICER Iγ and ZsGreen1 cDNA expressing green fluorescence protein,

both which are controlled by the TRE promoter. This unitary vector

was linearized and integrated into the genomic DNA of the porcine

fibroblasts. Genomic DNA was isolated from G418-resistant

fibroblast colonies and was identified with specific primer sets

indicated by the arrows (a, a′, b, b′). (B) The PCR products with

primer a and a′ represents the chromosomal insertion of the

activator cassette. (C) Whether the same fibroblast colonies had

responder cassette was confirmed using primer b and b′. IRES,

internal ribosomal entry site; SM, size marker; NC, negative

control; ICER Iγ, inducible cyclic AMP early repressor Iγ; tTa,

tet-controlled transactivator; TRE, tTA-response element. |

Generation and characterization of

fibroblast cell lines containing the dox-inducible porcine ICER Iγ

construct

The dox-inducible porcine ICER Iγ vector was

linearized and used to transfect miniature pig fibroblasts using a

liposomal-mediated gene delivery system. The transfected

fibroblasts were selected and maintained with a medium containing

G418 (250 μg/ml) for four weeks. Chromosomal integration of the

targeting vector was confirmed by a PCR-based method using primer

sets specific for the vector (Table

I). Genomic DNA extracted from G418-resistant colonies was

amplified with primers a and a′ (product size, 992 bp; Fig. 1B) or primers b and b′ (product

size, 1,585 bp; Fig. 1C). In

total, 12 positive colonies were obtained following two rounds of

transfection (Table II).

Fibroblasts from the positive colonies may serve as a cellular

source for somatic cell nuclear transfer to generate a porcine

model that overexpresses ICER Iγ in a dox-inducible,

pancreas-specific manner.

| Table IITransfection efficiencies of the

porcine fibroblasts. |

Table II

Transfection efficiencies of the

porcine fibroblasts.

| Colony (n) |

|---|

|

|

|---|

| Transfection trials

(n) | G418 resistant | PCR positive |

|---|

| 2 | 12 | 12 |

Observation of dox-inducible fluorescence

in MIN6 cells and porcine fibroblasts

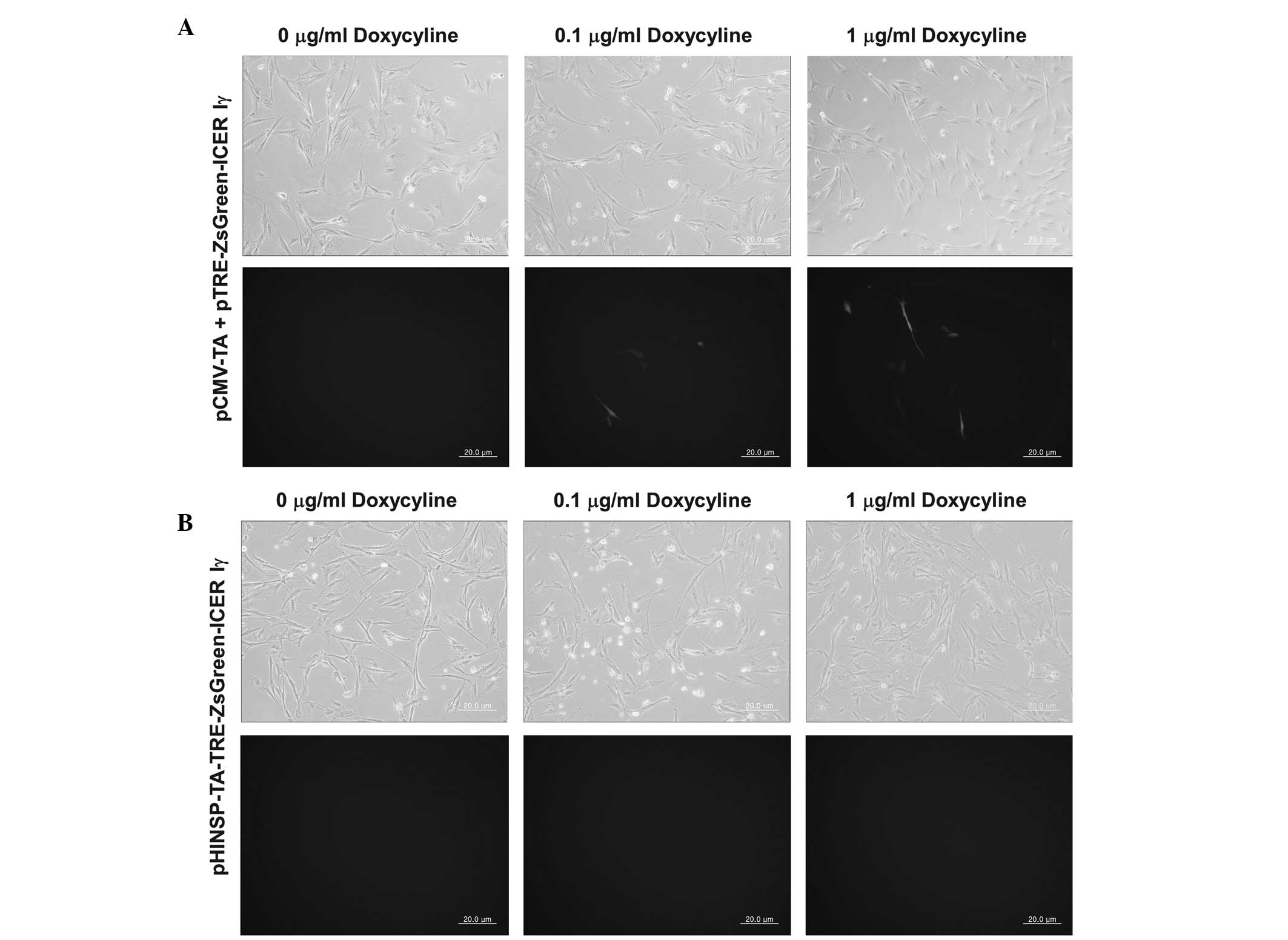

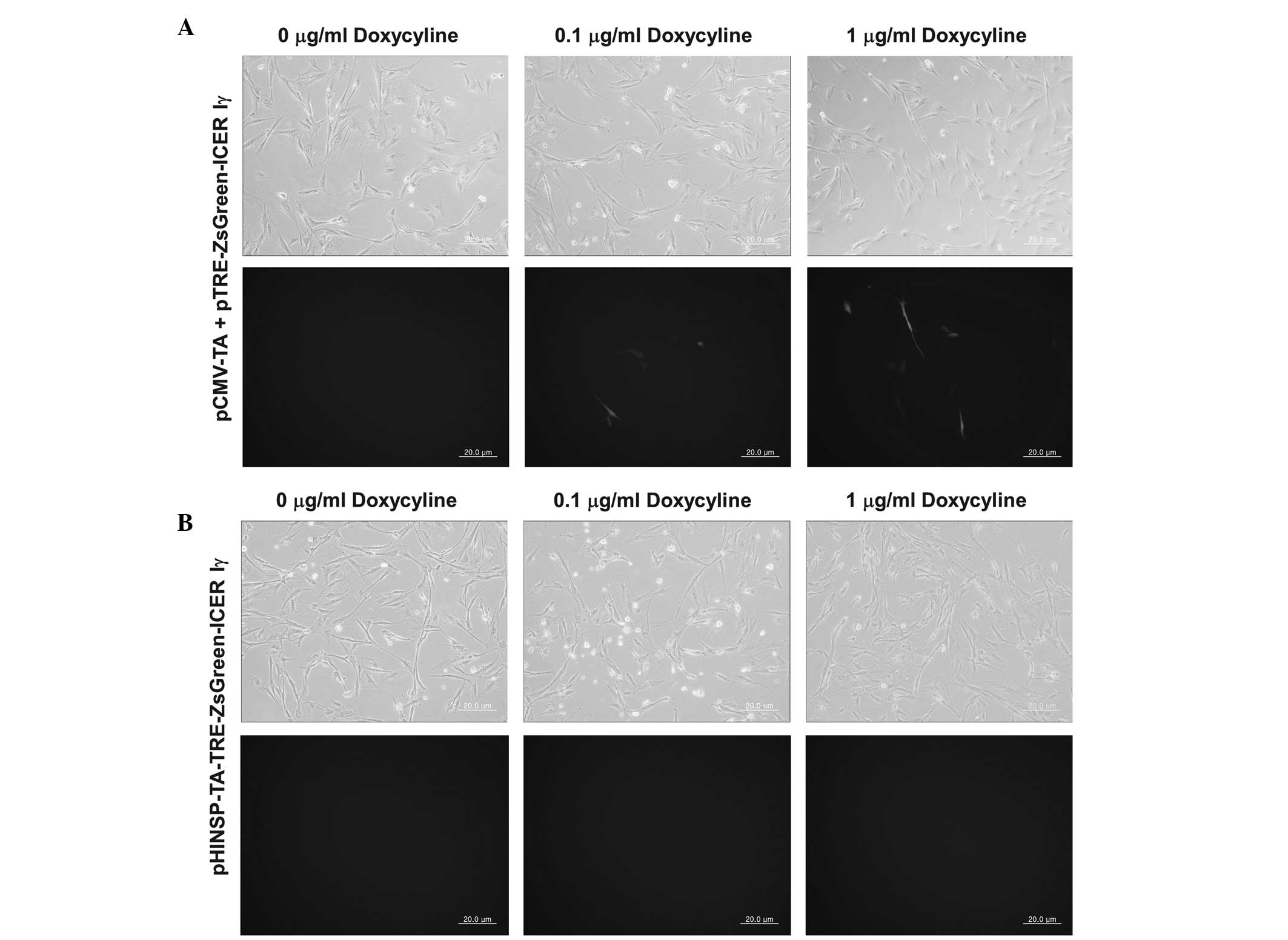

To observe tissue-specific expression, we

transiently transfected mouse pancreatic β-cells (MIN6) and porcine

non-pancreatic fibroblasts. The cells were co-transfected with

pCMV-TA and pTRE-ZsGreen1-ICER Iγ constructs as a positive control

to confirm the activity of the dox-inducible expression system. In

the MIN6 cells expressing pHINSP-TA-TRE-ZsGreen-ICER Iγ, we

observed green fluorescence indicative of dox-inducible and

pancreas-specific ICER Iγ expression (Fig. 2). In this regard, green

fluorescence was also confirmed following dox treatment in a

dose-dependent manner (0, 0.1 and 1 μg/ml). However, no

fluorescence was observed in either the untreated or dox-treated

porcine fibroblasts transiently transfected with

pHINSP-TA-TRE-ZsGreen-ICER Iγ due to the pancreas specific insulin

promoter (Fig. 3).

| Figure 2Observation of dox-inducible green

fluorescence in mouse β-cell line, MIN6, by transient transfection

of pCMV-TA with (A) pTRE-ZsGreen-ICER Iγ or (B) unitary

pHINSP-TA-TRE-ZsGreen-ICER Iγ. In the MIN6 cell line, dox-inducible

and pancreas specific expression of green fluorescence by human

insulin promoter was observed. Furthermore, the green fluorescence

demonstrated dox-dose dependent expression, as treated dox

concentration was increased to 0, 0.1 and 1 mg/ml. CMV,

cytomegalovirus promoter; TA, tet-on transcription activator;

HINSP, human insulin promoter; ICER Iγ, inducible cyclic AMP early

repressor Iγ; TRE, tTA-response element. |

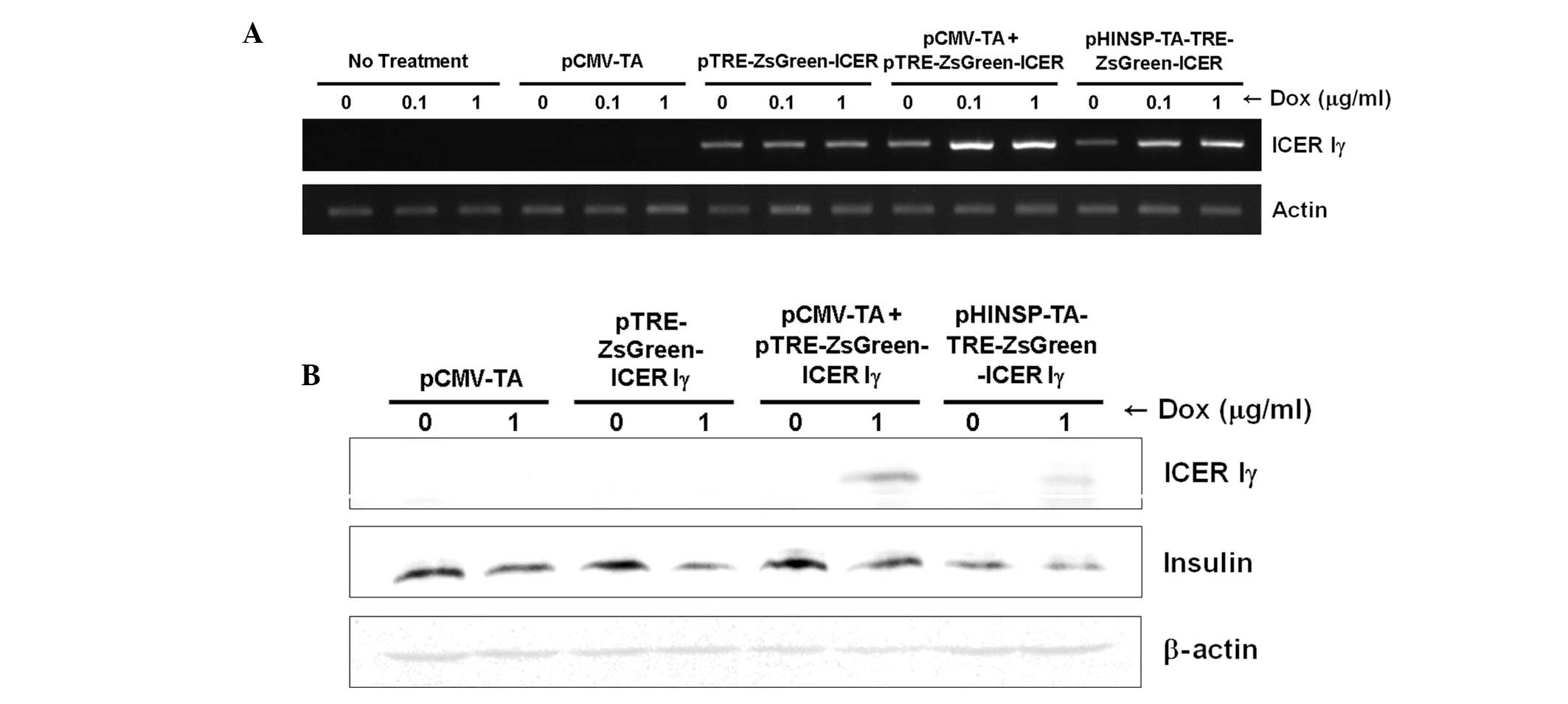

Dox-inducible porcine ICER Iγ mRNA

expression in mouse β-cells

To evaluate dox-inducible ICER Iγ expression under

the control of the human insulin promoter, reverse transcription

(RT)-PCR was performed using mRNA obtained from transiently

transfected MIN6 cells and porcine fibroblasts. Consistent to the

fluorescence microscopy findings, dox-dose dependent and pancreas

specific mRNA expression of ICER Iγ was observed in MIN6 cells

(Fig. 4A) following dox treatment

but not in porcine fibroblasts (data not presented). Additionally,

the expression levels of ICER Iγ in cells transfected with only

pCMV-TA or pTRE-ZsGreen1-ICER Iγ were unchanged regardless of the

absence or presence of dox. Although ICER Iγ expression in MIN6

cells expressing the pTRE-ZsGreen1-ICER Iγ transgene was observed,

the level was consistently low and unaffected regardless of the

presence of dox. It should be considered that unknown factors of

the transcriptional environment may regulate the gene expression of

in vitro systems through introduction of the target

gene.

Insulin production in mouse β-cells

expressing the dox-inducible porcine ICER Iγ gene

Since the ICER Iγ transgene represses insulin

production in vivo (7,8),

western blot analysis was performed to determine whether

dox-inducible expression of porcine ICER Iγ may inhibit insulin

generation. The expression of insulin was evaluated in transiently

transfecting MIN6 cells with four combinations of the constructs

(Fig. 4B). ICER Iγ protein in

cells transfected with only pCMV-TA or pTRE-ZsGreen1-ICER Iγ was

not expressed regardless of the absence or presence of dox.

Dox-inducible expression of ICER Iγ was observed in cells

co-transfected with pCMV-TA and pTRE-ZsGreen1-ICER Iγ, or

transfected with pHINSP-TA-TRE-ZsGreen1-ICER Iγ alone. By contrast,

insulin expression was decreased in the presence of dox. These

findings indicated that dox-inducible ICER Iγ expression decreases

insulin expression in mouse pancreas β-cell. Therefore, the

extensive induction of ICER Iγ expression may interfere with

insulin synthesis and promote the development of type 1 diabetes

mellitus. As a result, our dox-inducible ICER Iγ expression system

may be a useful tool for studying diabetes mellitus and

pre-diabetes in humans by controlling ICER Iγ expression levels

through dox administration.

Discussion

In rodent models, it has been reported that ICERs

have an important role in T-cell mediated downregulated expression

of interleukin (IL)-2, an essential growth factor for

auto-aggressive T-effector cells (15,16).

In pancreatic β-cells, ICER Iγ suppresses not only insulin gene

transcription but also cell replication via the reduction of cyclin

A levels (7,17). Therefore, the prolonged or

constitutive expression of ICER results in the development of

pathological conditions (7)

similar to severe cases of diabetes mellitus, because ICER Iγ

overexpression significantly blocks CRE-mediated transcription by

competing with CRE-binding activators (6,18).

Therefore, in the present study, a tissue-specific ICER Iγ vector

was constructed, whose expression was controlled by dox, and a

porcine fibroblast cell line with this construct was also

established to generate transgenic piglets.

The insulin promoter directly regulates insulin gene

transcription according to plasma glucose levels and enables

β-cells to produce insulin (19,20).

On this basis, the insulin promoter was utilized in the present

study as a β-cell-specific regulator of gene transcription. The

human insulin promoter region spanning −1,431 to +1 nt

significantly increased ICER Iγ gene expression in MIN6 cells in

the presence of high glucose levels and dox (Fig. 4A). However, induction of ICER Iγ

expression in MIN6 cells slightly downregulated insulin production

(Fig. 4B). It was hypothesized

that the activity of the porcine ICER Iγ protein would not be

maximized in mouse β-cells because the porcine ICER Iγ protein is

documented as having 92.6–94.4% identity to mouse ICERs, using a

BLAST tool. By contrast, it may be possible to reduce the

interaction between porcine ICER Iγ and mouse insulin promoter

regulatory elements.

It was reported that the relative number and

composition of principal insulin promoter regulatory elements in

different species was determined through transcription factor

binding site turnover and accretion (21–23).

In particular, CRE is a key determinant of gene expression

(24,25) and binds to the widest array of

transcription factors in the insulin promoter (26). Unlike the human insulin promoter

that contains four copies of CREs, the mouse insulin promoter only

has a single copy (23). For this

reason, the binding rate of overexpressed ICER Iγ within the mouse

insulin promoter may decrease and the repression of insulin

expression by ICER Iγ may be weaker in spite of ICER Iγ

overexpression via the human insulin promoter in mouse β-cells.

MIN6 cells were derived from a transgenic C57BL/6

mouse insulinoma expressing an insulin-promoter/T-antigen construct

and possess characteristics of pancreatic β-cells, including the

ability to secrete insulin in response to glucose (27,28).

Although the amount of insulin secreted from MIN6 cells in the

presence of a high (25 mM) glucose concentration is six-to

seven-fold greater than that observed with a low (5 mM) glucose

level, it has been noted that glucose-induced insulin secretion

from the MIN6 cells may suddenly be lost during the course of

passaging (28). This may result

in a poor response to the downregulation of glucose-mediated

insulin production via dox-inducible ICER Iγ expression.

To generate a porcine model for diabetes or

metabolic syndromes, pig fibroblast cell lines expressing

dox-inducible ICER Iγ were established. These cells should be a

useful source for somatic cell nuclear transfer procedures. Porcine

models provide various advantages for studying human metabolic

syndromes because pigs are mono-gastric omnivores and have

anatomical/physiological characteristics similar to that of humans

(29). The porcine model

established using the created cells may offer information crucial

for understanding the mechanisms underlying human diabetes

mellitus.

In the present study, the dox-inducible,

tissue-specific expression of the transcriptional repressor ICER Iγ

was observed in a mouse pancreatic β-cell line. This result was

compared with the expression of ICER Iγ observed in transiently

transfected primary porcine fibroblasts. The unitary tet-on ICER Iγ

induction system was pancreas-specific and dox-inducible. When

generating transgenic animals, these cellular traits may reduce

stillbirth rates during pregnancy and unwanted outcomes caused by

uncontrollable gene expression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the

Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (no. PJ00956301), Rural

Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

|

1

|

Leonard J, Serup P, Gonzalez G, Edlund T

and Montminy M: The LIM family transcription factor Isl-1 requires

cAMP response element binding protein to promote somatostatin

expression in pancreatic islet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

89:6247–6251. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Barnett DW, Pressel DM, Chern HT, Scharp

DW and Misler S: cAMP-enhancing agents ‘permit’ stimulus-secretion

coupling in canine pancreatic islet beta-cells. J Membr Biol.

138:113–120. 1994.

|

|

3

|

Ortmeyer HK: Insulin decreases skeletal

muscle cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) activity in normal

monkeys and increases PKA activity in insulin-resistant rhesus

monkeys. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 8:223–235. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Seino S, Takahashi H, Fujimoto W and

Shibasaki T: Roles of cAMP signalling in insulin granule

exocytosis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 11(Suppl 4): 180–188. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Foulkes NS, Borrelli E and Sassone-Corsi

P: CREM gene: use of alternative DNA-binding domains generates

multiple antagonists of cAMP-induced transcription. Cell.

64:739–749. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mioduszewska B, Jaworski J and Kaczmarek

L: Inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) in the nervous system - a

transcriptional regulator of neuronal plasticity and programmed

cell death. J Neurochem. 87:1313–1320. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Inada A, Hamamoto Y, Tsuura Y, Miyazaki J,

Toyokuni S, Ihara Y, Nagai K, Yamada Y, Bonner-Weir S and Seino Y:

Overexpression of inducible cyclic AMP early repressor inhibits

transactivation of genes and cell proliferation in pancreatic beta

cells. Mol Cell Biol. 24:2831–2841. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Inada A, Someya Y, Yamada Y, Ihara Y,

Kubota A, Ban N, Watanabe R, Tsuda K and Seino Y: The cyclic AMP

response element modulator family regulates the insulin gene

transcription by interacting with transcription factor IID. J Biol

Chem. 274:21095–21103. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gossen M and Bujard H: Tight control of

gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive

promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 89:5547–5551. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhou X, Vink M, Klaver B, Berkhout B and

Das AT: Optimization of the Tet-On system for regulated gene

expression through viral evolution. Gene Ther. 13:1382–1390. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Müller

G, Hillen W and Bujard H: Transcriptional activation by

tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 268:1766–1769. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Saudek F: Gene therapy in the treatment of

diabetes mellitus. Cas Lek Cesk. 142:523–527. 2003.(In Czech).

|

|

13

|

Driver JP, Serreze DV and Chen YG: Mouse

models for the study of autoimmune type 1 diabetes: a NOD to

similarities and differences to human disease. Semin Immunopathol.

33:67–87

|

|

14

|

Jung EM, Kim YK, Lee GS, Hyun SH, Hwang WS

and Jeung EB: Establishment of inducible cAMP early repressor

transgenic fibroblasts in a porcine model of human type 1 diabetes

mellitus. Mol Med Rep. 6:239–245

|

|

15

|

Bodor J, Fehervari Z, Diamond B and

Sakaguchi S: ICER/CREM-mediated transcriptional attenuation of IL-2

and its role in suppression by regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol.

37:884–895. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bodor J, Spetz AL, Strominger JL and

Habener JF: cAMP inducibility of transcriptional repressor ICER in

developing and mature human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

93:3536–3541. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Inada A, Weir GC and Bonner-Weir S:

Induced ICER Igamma down-regulates cyclin A expression and cell

proliferation in insulin-producing beta cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 329:925–929. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Molina CA, Foulkes NS, Lalli E and

Sassone-Corsi P: Inducibility and negative autoregulation of CREM:

an alternative promoter directs the expression of ICER, an early

response repressor. Cell. 75:875–886. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Odagiri H, Wang J and German MS: Function

of the human insulin promoter in primary cultured islet cells. J

Biol Chem. 271:1909–1915. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Burkhardt BR, Loiler SA, Anderson JA,

Kilberg MS, Crawford JM, Flotte TR, Goudy KS, Ellis TM and Atkinson

M: Glucose-responsive expression of the human insulin promoter in

HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1005:237–241. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rockman MV and Wray GA: Abundant raw

material for cis-regulatory evolution in humans. Mol Biol Evol.

19:1991–2004. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ludwig MZ and Kreitman M: Evolutionary

dynamics of the enhancer region of even-skipped in Drosophila. Mol

Biol Evol. 12:1002–1011. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hay CW and Docherty K: Comparative

analysis of insulin gene promoters: implications for diabetes

research. Diabetes. 55:3201–3213. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Daniel PB, Walker WH and Habener JF:

Cyclic AMP signaling and gene regulation. Annu Rev Nutr.

18:353–383. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Inagaki N, Maekawa T, Sudo T, Ishii S,

Seino Y and Imura H: c-Jun represses the human insulin promoter

activity that depends on multiple cAMP response elements. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 89:1045–1049. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Foulkes NS and Sassone-Corsi P:

Transcription factors coupled to the cAMP-signalling pathway.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1288:F101–F121. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ishihara H, Asano T, Tsukuda K, Katagiri

H, Inukai K, Anai M, Kikuchi M, Yazaki Y, Miyazaki JI and Oka Y:

Pancreatic beta cell line MIN6 exhibits characteristics of glucose

metabolism and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion similar to

those of normal islets. Diabetologia. 36:1139–1145. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Miyazaki J, Araki K, Yamato E, Ikegami H,

Asano T, Shibasaki Y, Oka Y and Yamamura K: Establishment of a

pancreatic beta cell line that retains glucose-inducible insulin

secretion: special reference to expression of glucose transporter

isoforms. Endocrinology. 127:126–132. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Petersen B, Carnwath JW and Niemann H: The

perspectives for porcine-to-human xenografts. Comp Immunol

Microbiol Infect Dis. 32:91–105. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|