Introduction

Myocardial ischemic injury is a common pathological

process in patients suffering from cardiac conditions, including

atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, acute myocardial

infarction and cardiac transplantation (1). However, the treatment costs for these

diseases are high; therefore, it is important to investigate

low-cost therapies that impede ischemia-induced myocardial

injury.

The mechanisms underlying ischemia-induced cell

damage are complicated and remain elusive. Increasing evidence

suggested that oxidative stress is important in myocardial ischemic

injury (2). Oxidative stress is

characterized by marked increases in the production of reactive

oxygen species (ROS), including the superoxide anion

(O2•−) and the hydroxyl radical (·OH), as

well as non-radical molecules, including hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) and singlet oxygen

(1O2) (3,4).

Environmental stress factors, including ultraviolet rays, heat

exposure, as well as ischemia and/or hypoxia, are major causes of

oxidative stress, which may damage proteins, lipids and DNA, and

eventually result in cellular death or the development of cancer

(5,6). Under normal conditions, intracellular

ROS levels are controlled by balancing ROS generation with ROS

elimination. Once the balance is disrupted, for instance, through

increased ROS generation and/or reduced elimination, ROS may

aggregate and oxidative stress arises. Eliminating excessive ROS

and enhancing endogenous antioxidation ability have been applied

clinically (7), and in myocardial

ischemic injury, oxidant scavengers, antioxidant extracts, vitamin

E and vitamin C have all demonstrated to have a potential

therapeutic value (8). However,

water-soluble vitamin C has a low transmembrane diffusion ability

and it is difficult to accumulate vitamin C up to an effective

level to eliminate ROS (9).

Conversely, the lipid-soluble vitamin E is difficult to dissolve in

the cytoplasm in order to neutralize ROS (10). These shortcomings have limited the

wide clinical use of the two vitamins. Therefore, a small

antioxidant with water- and lipid-solubility is expected to have

greater application value.

Hydrogen (H2) gas is an inexpensive

medical gas generated by electrolysis of water. Similar to other

gaseous molecules, including nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide

(CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S), H2 gas has

been demonstrated to exhibit numerous important cytoprotective

effects in the nervous, cardiovascular and digestive systems

(11–14). Unlike vitamin C and vitamin E,

H2 gas dissolves in water and lipids. In addition, the

simple molecular structure and small molecular weight render

H2 gas a good antioxidant candidate in cells. A number

of studies have suggested that H2 gas may selectively

scavenge ·OH free radicals (15,16).

Therefore, H2 gas may have broad clinical applications

in the future. However, in cardiomyocytes, it has not been reported

whether H2 gas protects against ischemia-induced injury

in vitro, which was the focus of the present study.

Abundant evidence indicated that enhancement of

endogenous antioxidation activity exerts cardioprotective effects.

For instance, upregulation of superoxide dismutase (SOD) or heme

oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia and/or

reperfusion-induced damage (17–19).

Notably, in addition to scavenging ·OH free radicals, H2

gas protection has been associated with induction of HO-1

controlled by NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) in rat lung

transplant-induced injury and paraquat-induced oxidative damage in

plants (20,21). H2 gas protection of

cardiomyocytes may therefore be associated with scavenging ·OH free

radicals and upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

H9c2 cardiomyoblasts (H9c2 cells), originating from

rat heart ventricular tissue, have widely served as an in

vitro model for cardiac muscle in virtue of their morphological

features and biochemical properties (22). In the present study, H9c2 cells

were subjected to serum and glucose deprivation (SGD) or exposed to

hypoxia provoked by a chemical hypoxia-mimicking agent, cobalt

chloride (CoCl2), to establish an

ischemia/hypoxia-induced myocardial injury model. H2

gas-rich medium was applied to investigate the cytoprotection,

antioxidation and activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway as

well as the involvement of scavenging ·OH free radicals and

upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in the

cardioprotection by H2 gas.

Materials and methods

Materials

CoCl2 and protoporphyrin IX zinc (II)

(ZnPP IX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Brusatol (BR), an inhibitor of Nrf2, was provided by BOC Sciences

(Shirley, NY, USA). A cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased

from Dojindo Laboratories (Kyushu, Japan). Specific monoclonal

primary antibodies against rat HO-1 and Nrf2 proteins were obtained

from EPITOMICS of Abcam Company (Burlingame, CA, USA). High glucose

and glucose-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and fetal

bovine serum (FBS) were supplied by Gibco-BRL (Grand Island, NY,

USA). A bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit was purchased

from Kangchen Bio-tech Inc. (Shanghai, China). An enhanced

chemiluminescence (ECL) kit was obtained from Applygen Technologies

Inc. (Beijing, China). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

kit for detection of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) was

provided by Abnova Corporation (Taipei, Taiwan).

Cell culture

H9c2 cells were supplied by the Cell Bank at the

Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences

(Shanghai, China). The cells were maintained in high glucose DMEM

supplemented with 15% FBS at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5%

CO2 and 95% air. The cells were passaged approximately

every two days after digestion with 0.2% trypsin.

Hypoxia or ischemia treatment

CoCl2, a chemical hypoxia inducer, was

co-incubated with H9c2 cells to induce hypoxia. An ischemia-induced

myocardial injury model generated through SGD was prepared in

vitro in the cell medium. The cell viability was used to

indicate the extent of hypoxic or ischemic injury in the H9c2

cells.

Preparation of H2 gas-rich

medium

Pure H2 gas (99.999% purity) was produced

via electrolysis of water with a M177021 H2 gas

generator, supplied by Beijing Midwest Yuanda Technology Co., Ltd.

(Beijing, China; 23). H2 gas-rich medium was prepared

freshly prior to saturating the medium with the generated

H2 gas for at least 30 min.

Determination of cell viability

Cell viability was analyzed by a CCK-8 assay

following the manufacturer’s instructions. H9c2 cells were plated

in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells/well. When the cells

were grown to ~70% confluence, the indicated treatments were

administered. At the end of the treatment, the CCK-8 solution (10

μl) at 1:10 dilution with FBS-free DMEM high glucose medium (100

μl) was added to each well followed by a further 3 h incubation at

37°C. Absorbance (A) was measured at 450 nm with a microplate

reader produced by Molecular Devices, LLC (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The

mean A was used to calculate the percentage of cell viability

according to the following equation: Percentage of viable cells =

(A treatment group − A Blank group)/(A Control group-A Blank group)

× 100%. Experiments were performed six times (24).

Western blot analysis of protein

expression

H9c2 cells were plated in 60-mm diameter petri

dishes. Following the indicated treatments, the cells were

harvested and total proteins or nuclear proteins were extracted and

quantified with the BCA kit and used to measure HO-1 or Nrf2

expression levels, respectively. Subsequent to denaturation by

heating at 100°C for 5 min, equal quantities of proteins of the

indicated groups were loaded and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. The

proteins in the gel were then transferred to a polyvinylidene

fluoride membrane. Following blocking with 5% fat-free milk in

Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T), the membranes were

incubated with rat monoclonal primary antibodies against HO-1 or

Nrf2 overnight with gentle agitation at 4°C. β-actin and Lamin B

served as loading controls. Subsequent to three washes with TBS-T,

the membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for

1 h. The membranes were washed again and developed with an ECL

system. The membranes were then exposed to X-ray films (Kodac

Company, Beijing, China). The integrated optical density of the

protein bands was calculated by Image J 1.47 Software (National

Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Competitive ELISA for measurement of

8-OHdG

Intracellular ·OH free radicals cause oxidative

damage to DNA to form 8-OHdG. Therefore, by measuring 8-OHdG levels

in the cells, ·OH free radical content may be analyzed indirectly.

H9c2 cells were plated in six-well plates and treated as indicated.

At the end of the treatment, the cells were harvested and lysed.

8-OHdG levels in the lysate were determined according to the

manufacturer’s instructions (Abnova Corporation). The experiment

was performed at least six times with similar outcomes.

Gene knockdown

Small interfering RNA (Si-RNA) against rat Nrf2 mRNA

(GenBank accession no. AF037350; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) was synthesized

by GenePharma Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The Si-RNA of Nrf2

(Si-Nrf2) and random non-coding RNA (Si-NC) were transfected into

H9c2 cells using Lipofectamine 2000, according to the

manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Life Technologies,

Carlsbad, CA, USA). Si-Nrf2 and Si-NC (20 nmol/l) were incubated

with the cells for 6 h followed by further incubation for 24 h in

order to transfect the cells.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0 software

(SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and the results are expressed as the

mean ± standard deviation. The significance of intergroup

differences was evaluated by one-way analyses of variance.

Differences were considered to be significant if the two-sided

probability (P) was <0.05.

Results

H2 gas-rich medium does not

affect chemical hypoxia-induced myocardial injury

Hypoxemia can be imitated in vitro by

chemical hypoxia or SGD treatment. H2 gas protection in

chemical hypoxia-induced myocardial injury was firstly assessed by

treatment of H9c2 cells with CoCl2 in H2

gas-rich medium. As shown in Fig.

1A, treatment of H9c2 cells with increasing concentrations of

CoCl2 significantly reduced cell viability at

concentrations of 400–1,000 μM. In order to observe H2

gas effectiveness, the cell culture medium was saturated with

H2 gas generated by electrolysis of water. No difference

in cell viability between the cells cultivated in H2

gas-rich medium and those cultivated in H2 gas-free

medium was identified under the conditions of CoCl2

exposure or rest (Fig. 1B). This

result indicated that H2 gas treatment did not influence

chemical hypoxia-induced myocardial injury.

H2 gas-rich medium alleviates

SGD-induced cell injury

SGD treatment acts as another in vitro

hypoxemia model by withdrawing FBS and glucose to mimic acute

infarction-induced myocardial injury in vivo. When the cells

were exposed to SGD for different time periods followed by further

culture for 30 h, the cell viability of H9c2 cells was

significantly reduced (P<0.01; Fig.

2A). Following exposure to SGD for 6–18 h, the H9c2 cells were

cultured in H2 gas-rich medium for 30 h. The findings

demonstrated that, compared with H2 gas-free culture,

H2 gas-rich culture significantly increased the

viability of the cells subjected to SGD for 6 or 12 h (P<0.05),

but not 18 h. The results suggested that when the cell injury

induced by SGD was not severe, H2 gas was able to

promote cell survival.

| Figure 2Effects of H2 gas on

SGD-induced injury in H9c2 cells. Following the indicated

treatments, cell viability was measured with a cell counting kit-8

assay. (A) H9c2 cells were exposed to SGD between 6 and 30 h,

followed by a further 30 h in normal culture. (B) H9c2 cells were

exposed to SGD for 6, 12 or 18 h, respectively, in the absence

(H2-Free) or presence (H2-Rich) of

H2 gas treatment. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation, n=6. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, compared with the control group.

§P<0.05, compared with the SGD group. SGD, serum and

glucose deprivation. |

H2 gas-rich medium prevents

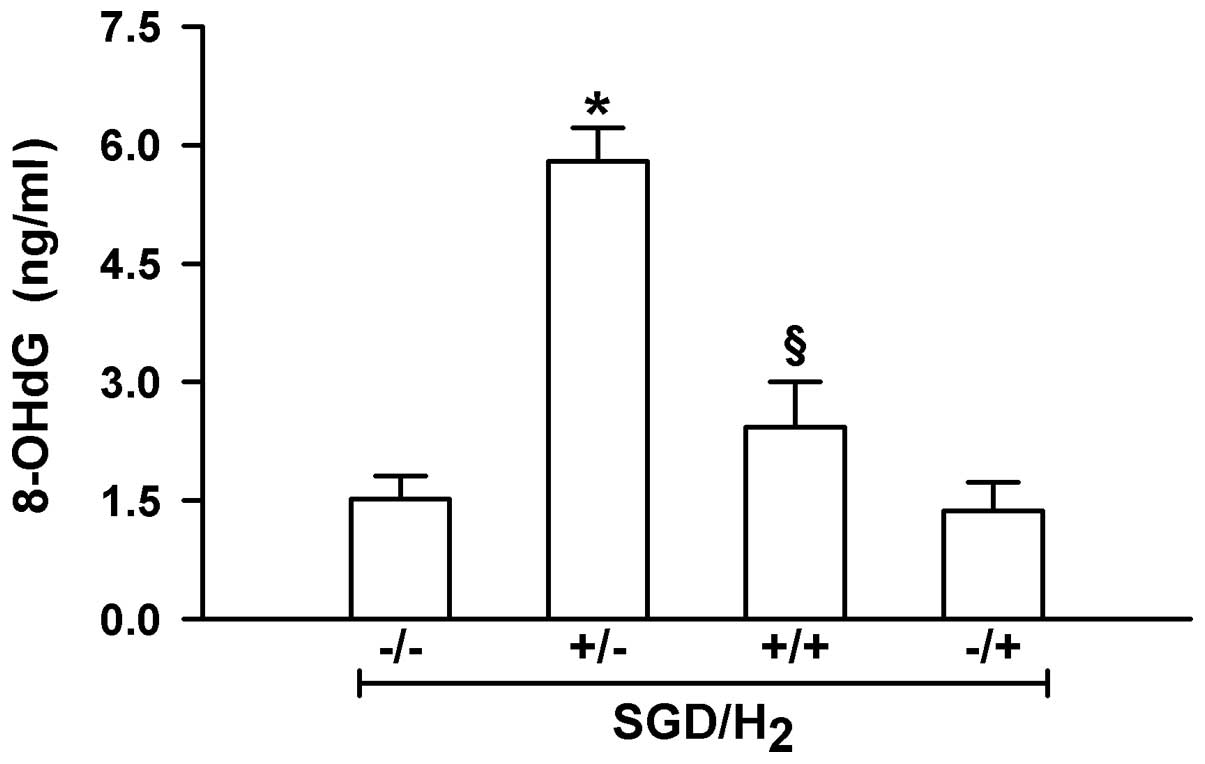

SGD-induced ·OH free radical generation

One mechanism underlying H2 protection is

ROS scavenging, particularly of ·OH free radicals. To investigate

whether H2 gas-mediated myocardial protection was

associated with scavenging ·OH free radicals, the ·OH levels in

H9c2 cells were measured using ELISA. As shown in Fig. 3, exposure of the cells to SGD

significantly enhanced intracellular ·OH levels (P<0.01).

However, this effectiveness was significantly inhibited by

incubation in H2 gas-rich medium (P<0.01). This

indicated that the elimination of ·OH free radicals may be an

important mechanism of myocardial protection by H2

gas.

Adaptive HO-1 induction contributes to

H2 gas inhibition of SGD-induced injury in H9c2

cells

HO-1 is endogenously produced, functioning as an

antioxidation enzyme. In order to examine the role of HO-1 in

SGD-induced myocardial injury, experiments to detect HO-1 levels

were performed. The data in Fig. 4

show that exposure of H9c2 cells to SGD significantly upregulated

HO-1 levels when compared with the cells under normal conditions

(P<0.01). When the HO-1 inhibitor ZnPP IX was administered,

SGD-induced cellular injury was found to be significantly

aggravated (P<0.05; Fig. 5).

These results suggested that HO-1 was beneficial in SGD-induced

injury in H9c2 cells.

Upregulation of HO-1 is involved in

H2 gas-induced myocardial protection

H2 gas-induced protection is not only

associated with simple elimination of ·OH free radicals, but also

with induction of endogenous genes, for instance, HO-1 (20,21).

To clarify whether HO-1 is involved in H2 gas-induced

myocardial protection, experiments were conducted to observe the

effect of H2 gas on SGD-triggered HO-1 upregulation and

the effect of HO-1 inhibition on H2 gas-induced

protection of H9c2 cells. The data in Fig. 4 reveal that exogenously applied

H2 gas significantly enhanced the upregulation elicited

by SGD in H9c2 cells (P<0.05). Notably, inhibition of HO-1 with

10 μM ZnPP IX significantly reduced the H2 gas-induced

increase in cellular viability following SGD treatment (P<0.05;

Fig. 6). The results suggested

that HO-1 at least partially mediated the protection from ischemia

provided by H2 gas in H9c2 cells.

H2 gas facilitates

nuclear Nrf2 expression induced by SGD in H9c2 cells.

Nrf2 is a transcription factor responsible for HO-1

expression. To address the role of Nrf2 in H2

gas-induced myocardial protection, the effect of H2

gas-rich medium on the changes of Nrf2 levels induced by SGD was

investigated. As shown in Fig. 7,

the SGD challenge resulted in a significant increase in nuclear

Nrf2 expression levels, indicating its activation under SGD

conditions in H9c2 cells (P<0.05). Notably, H2 gas

application following SGD exposure induced a significant increase

in nuclear Nrf2 expression levels (P<0.05). Inhibition of Nrf2

with 10 μM BR significantly reduced myocardial protection by

H2 gas (P<0.05, Fig.

8).

In addition, genetic silencing of Nrf2 by RNAi

(Si-Nrf2) also significantly inhibited H2 gas-elicited

HO-1 induction (P<0.05, Fig. 9)

and myocardial protective action (P<0.05, Fig. 8). These results indicated that the

H2 gas protection from SGD-induced injury in H9c2 cells

was at least in part mediated through the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling

pathway.

Discussion

The results of the present study suggested that

H2 gas exhibited myocardial protection against

ischemia-induced injury in H9c2 cells in vitro through

elimination of ·OH free radicals and activation of the Nrf2/HO-1

signaling pathway. These findings provide further evidence of

H2 gas protection and deepen the understanding of the

molecular mechanisms involved.

H2 gas is a gas with novel medical

application, in addition to NO, CO and H2S, whose

cytoprotective effects have gradually gained attention (15). The cytoprotective effect of

H2 gas has been investigated in the nervous,

cardiovascular and digestive systems (11–14).

In the present study, myocardial protection by H2 gas

was investigated in two distinct models: Chemical hypoxia-induced

injury and SGD-induced injury in H9c2 cells. Treatment with

chemical hypoxia-mimicking agent CoCl2, at 400–1,000 μM

for 24 h, reduced cell viability in a concentration-dependent

manner, although no effect of H2 gas on

CoCl2-induced injury was observed. The effect of

H2 gas on SGD-induced injury was then analyzed. Notably,

H2 gas exerted marked myocardial protection, since its

application impeded SGD-induced injury in H9c2 cells. These

findings were in accordance with a study by Sun et al

(29) on cardiac

ischemia/reperfusion injury in a rat model. However, the findings

of the present study also indicated that although CoCl2

(25,26) and SGD (27) are frequently used in

hypoxia/ischemia in vitro models, they may possess markedly

different underlying injury mechanisms. In addition, as

H2 gas is a water- and lipid-soluble and simple

molecule, H2 gas may exhibit a greater clinical

antioxidative value than the water-soluble vitamin C and

lipid-soluble vitamin E.

Oxidative stress is critical in myocardial ischemic

damage through overproduction of ROS (2). ROS in mammals include

O2•−, H2O2 and ·OH.

O2•−, H2O2 ROS are

eliminated by corresponding enzymes. For example,

O2•− may be catalyzed into O2 and

H2O2 via dismutation (28), and H2O2, one

of the most powerful oxidizers, may be converted into

H2O by catalase or guaiacol peroxidase, but may also be

converted into ·OH. Although ·OH free radicals are toxic to cells,

enzymes responsible for ·OH elimination remain to be identified.

Therefore, it is important for antioxidants to eliminate ·OH free

radicals and/or inhibit the production of ·OH. In the present

study, exposure of H9c2 cells to SGD was found to significantly

increase intracellular ·OH free radical levels as identified

through assessment of 8-OHdG. The ·OH levels after SGD stimulation

were significantly reduced during cell cultivation in H2

gas-rich medium, in concurrence with previous reports (15,16,29).

Increasing evidence suggested that the

cytoprotective effect of H2 gas is not only associated

with simple elimination of ·OH free radicals, but also with

numerous signaling molecules (20,21).

A study on plants demonstrated that pretreatment with H2

gas enhanced the salt tolerance of arabidopsis through zinc-finger

transcription factor ZAT10/12 (30). Additionally, the HO-1 signaling

pathway has been observed to be involved in H2 gas

protection against paraquat-induced oxidative injury (21). In animals, Cai et al

(31) revealed that H2

gas treatment alleviated tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced rat

osteoblast inflammatory injury via upregulation of SOD activity.

Furthermore, evidence has indicated that HO-1 induction mediated

H2 gas mitigation of rat lung injury resulting from

transplantation (20). In the

present study, SGD exposure was found to markedly increase HO-1

expression. The mechanism of HO-1 in SGD-induced myocardial insult

was further elucidated using a selective HO-1 inhibitor, ZnPP IX.

Since the data indicated that the addition of ZnPP IX markedly

aggravated the SGD-induced insult, HO-1 may exhibit a protective

action against ischemia, a hypothesis which is supported by the

results of a study by Hwa et al (32). Notably, exogenously applied

H2 gas was found to result in a further increase in HO-1

expression; application of ZnPP IX partially abolished this

H2 gas-triggered myocardial protection. Therefore,

H2 gas protection may be partially mediated by HO-1

induction. One study suggested that inhalation of H2 gas

combined with CO, a product of HO-1, enhanced its therapeutic

efficacy in ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial injury

(33). These findings, alongside

those of the present study, support the hypothesis that the

mechanisms underlying H2 gas-induced myocardial

protection are not limited to the elimination of the ·OH free

radical and may also include upregulation of protective genes.

Nrf2 belongs to the NF-E2 superfamily of nuclear

basic leucine zipper transcription factors. Under conditions of

oxidative stress or pharmacological stimuli, Nrf2, as an adaptive

response, regulates phase II gene expression of numerous enzymes

that serve to detoxify pro-oxidative stressors (34). In the promoter region of certain

genes, such as HO-1 and SOD, Nrf2 binds to the cis-acting

regulatory element or enhancer sequence and induces gene expression

(35). In the present study, SGD

exposure markedly induced nuclear Nrf2 expression, which was

further enhanced by H2 gas administration. When the

action of Nrf2 was inhibited by BR, H2 gas-induced

myocardial protection was significantly attenuated. Studies have

indicated that BR may inhibit the Nrf2 signaling pathway (36,37).

In addition, genetic silencing of Nrf2 may also impede

H2-induced HO-1 expression and increases in cell

viability. These data suggested that the activation of Nrf2 is

involved in H2 gas protection and HO-1 induction. One

study observed that another medical gas, H2S, protected

cardiomyocytes against ischemia-induced injury by activation of the

Nrf2 signaling pathway (38).

Nrf2-mediated myocardial protection has also been reported

regarding a number of other compounds (39,40).

For instance, in the nervous system, curcumin protected rat brains

against focal ischemia via upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling

pathway (41). Therefore, the

upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway is considered to be

a general antioxidative mechanism of numerous drugs and compounds,

and this signaling pathway may represent a novel molecular target

of drug design.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that

H2 gas application not only directly scavenged ·OH free

radicals but also enhanced the expression of proteins of the

Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in SGD-stimulated H9c2 cells. These

findings provided basic information for the development of novel

treatments of ischemic myocardial injury with H2

gas.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Science & Technology

Planning Project of Guangdong Province in China (no.

2012A030400033).

References

|

1

|

Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, et al:

Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury

through AMPK- and COX-2-dependent mechanisms. Nat Med.

11:1096–1103. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Yang XY, Zhao N, Liu YY, et al: Inhibition

of NADPH oxidase mediates protective effect of cardiotonic pills

against rat heart ischemia/reperfusion injury. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2013:7280202013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Dickinson BC and Chang CJ: Chemistry and

biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress

responses. Nat Chem Biol. 7:504–511. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Devasagayam TP, Tilak JC, Boloor KK, Sane

KS, Ghaskadbi SS and Lele RD: Free radicals and antioxidants in

human health: current status and future prospects. J Assoc

Physicians India. 52:794–804. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Balliet RM,

Rivadeneira DB, et al: Oxidative stress in cancer associated

fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for

understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic

instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 9:3256–3276. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ryter SW, Kim HP, Hoetzel A, et al:

Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 9:49–89. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jha P, Flather M, Lonn E, Farkouh M and

Yusuf S: The antioxidant vitamins and cardiovascular disease. A

critical review of epidemiologic and clinical trial data. Ann

Intern Med. 123:860–872. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hamilton KL: Antioxidants and

cardioprotection. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 39:1544–1553. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Padayatty SJ, Katz A, Wang Y, et al:

Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease

prevention. J Am Coll Nutr. 22:18–35. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ingold KU, Webb AC, Witter D, Burton GW,

Metcalfe TA and Muller DP: Vitamin E remains the major

lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human plasma even in

individuals suffering severe vitamin E deficiency. Arch Biochem

Biophys. 259:224–225. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang C, Li J, Liu Q, et al: Hydrogen-rich

saline reduces oxidative stress and inflammation by inhibit of JNK

and NF-κB activation in a rat model of amyloid-beta-induced

Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 491:127–132. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zheng X, Mao Y, Cai J, et al:

Hydrogen-rich saline protects against intestinal

ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Free Radic Res. 43:478–484.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu Q, Shen WF, Sun HY, et al:

Hydrogen-rich saline protects against liver injury in rats with

obstructive jaundice. Liver Int. 30:958–968. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yu P, Wang Z, Sun X, et al: Hydrogen-rich

medium protects human skin fibroblasts from high glucose or

mannitol induced oxidative damage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

409:350–355. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ohsawa I, Ishikawa M, Takahashi K, et al:

Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing

cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med. 13:688–694. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Fukuda K, Asoh S, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto Y,

Ohsawa I and Ohta S: Inhalation of hydrogen gas suppresses hepatic

injury caused by ischemia/reperfusion through reducing oxidative

stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 361:670–674. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ambrosio G, Becker LC, Hutchins GM,

Weisman HF and Weisfeldt ML: Reduction in experimental infarct size

by recombinant human superoxide dismutase: insights into the

pathophysiology of reperfusion injury. Circulation. 74:1424–1433.

1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang X, Xiao Z, Yao J, Zhao G, Fa X and

Niu J: Participation of protein kinase C in the activation of Nrf2

signaling by ischemic preconditioning in the isolated rabbit heart.

Mol Cell Biochem. 372:169–179. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hui Y, Zhao Y, Ma N, et al: M3-mAChR

stimulation exerts anti-apoptotic effect via activating the

HIF-1α/HO-1/VEGF signaling pathway in H9c2 rat ventricular cells. J

Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 60:474–482. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kawamura T, Wakabayashi N, Shigemura N, et

al: Hydrogen gas reduces hyperoxic lung injury via the Nrf2 pathway

in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 304:L646–L656. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jin Q, Zhu K, Cui W, Xie Y, Han B and Shen

W: Hydrogen gas acts as a novel bioactive molecule in enhancing

plant tolerance to paraquat-induced oxidative stress via the

modulation of heme oxygenase-1 signalling system. Plant Cell

Environ. 36:956–969. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Branco AF, Pereira SL, Moreira AC, Holy J,

Sardão VA and Oliveira PJ: Isoproterenol cytotoxicity is dependent

on the differentiation state of the cardiomyoblast H9c2 cell line.

Cardiovasc Toxicol. 11:191–203. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Huang G, Zhou J, Zhan W, et al: The

neuroprotective effects of intraperitoneal injection of hydrogen in

rabbits with cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 84:690–695. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yang C, Yang Z, Zhang M, et al: Hydrogen

sulfide protects against chemical hypoxia-induced cytotoxicity and

inflammation in HaCaT cells through inhibition of ROS/NF-κB/COX-2

pathway. PLoS One. 6:e219712011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen SL, Yang CT, Yang ZL, et al: Hydrogen

sulphide protects H9c2 cells against chemical hypoxia-induced

injury. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 37:316–321. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yang Z, Yang C, Xiao L, et al: Novel

insights into the role of HSP90 in cytoprotection of H2S against

chemical hypoxia-induced injury in H9c2 cardiac myocytes. Int J Mol

Med. 28:397–403. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yao LL, Wang YG, Cai WJ, Yao T and Zhu YC:

Survivin mediates the anti-apoptotic effect of delta-opioid

receptor stimulation in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Sci. 120:895–907.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Elchuri S, Oberley TD, Qi W, et al:

CuZnSOD deficiency leads to persistent and widespread oxidative

damage and hepatocarcinogenesis later in life. Oncogene.

24:367–380. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sun Q, Kang Z, Cai J, et al: Hydrogen-rich

saline protects myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury in

rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 234:1212–1219. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xie Y, Mao Y, Lai D, Zhang W and Shen W:

H2 enhances arabidopsis salt tolerance by manipulating

ZAT10/12-mediated antioxidant defence and controlling sodium

exclusion. PLoS One. 7:e498002012.

|

|

31

|

Cai WW, Zhang MH, Yu YS and Cai JH:

Treatment with hydrogen molecule alleviates TNFα-induced cell

injury in osteoblast. Mol Cell Biochem. 373:1–9. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hwa JS, Jin YC, Lee YS, et al:

2-methoxycinnamaldehyde from Cinnamomum cassia reduces rat

myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury in vivo due to HO-1

induction. J Ethnopharmacol. 139:605–615. 2012.

|

|

33

|

Nakao A, Kaczorowski DJ, Wang Y, et al:

Amelioration of rat cardiac cold ischemia/reperfusion injury with

inhaled hydrogen or carbon monoxide, or both. J Heart Lung

Transplant. 29:544–553. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Fisher CD, Augustine LM, Maher JM, et al:

Induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes by garlic and allyl sulfide

compounds via activation of constitutive androstane receptor and

nuclear factor E2-related factor 2. Drug Metab Dispos. 35:995–1000.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kang KW, Lee SJ and Kim SG: Molecular

mechanism of nrf2 activation by oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 7:1664–1673. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Bauer AK, Hill T III and Alexander CM: The

involvement of NRF2 in lung cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2013:7464322013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ren D, Villeneuve NF, Jiang T, et al:

Brusatol enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by inhibiting the

Nrf2-mediated defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

108:1433–1438. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, et al:

Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling.

Circ Res. 105:365–374. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Deng C, Sun Z, Tong G, et al: α-Lipoic

acid reduces infarct size and preserves cardiac function in rat

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through activation of

PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. PLoS One. 8:e583712013.

|

|

40

|

Cui G, Shan L, Hung M, et al: A novel

Danshensu derivative confers cardioprotection via PI3K/Akt and Nrf2

pathways. Int J Cardiol. 168:1349–1359. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yang C, Zhang X, Fan H and Liu Y: Curcumin

upregulates transcription factor Nrf2, HO-1 expression and protects

rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 1282:133–141. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|