Introduction

There is evidence suggesting that myocardial

ischemia (MI) is a major risk factor of myocardial infarction,

which induces myocardial remodeling. The predominant morphological

changes of ventricular remodeling are the exhibition of an

infarction area, ventricular hypertrophy and ventricular expansion

(1,2). The mechanisms underlying ventricular

remodeling remain to be fully elucidated, however, it is generally

accepted that following myocardial injury, the molecules, cells and

mechanisms change due to altered gene expression levels and the

imbalance between cell apoptosis and proliferation, which is

important in the entire disease process (1).

It is important to develop novel treatments to

inhibit or slow the disease process to enable more time for

subsequent treatment. Traditional Chinese medicine has gained

increased attention for the treatment of various diseases. Although

the use of Chinese medicine in the treatment of ventricular

remodeling has been investigated only relatively recently, it has

been demonstrated that using traditional Chinese medicine can

affect the occurrence and development of ventricular remodeling in

a number of aspects (3). This is

also supported by previous reports suggesting that certain agents,

including statins, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and

angiotensin II receptor inhibitors, can improve ventricular

remodeling by increasing cell apoptosis and preventing cell

proliferation in smooth muscle cells in hypertensive animal models

(4,5).

Ginsenoside Rg3 (GSRg3), extracted from Panax

ginseng, is a traditional Chinese herbal medicine used widely

in clinical treatment and may significantly improve basilar artery

hypertrophic remodeling through the prevention of artery smooth

muscle cell proliferation (6). The

present study predominantly investigated how GSRg3 attenuates

MI/reperfusion (MI/R) injury and examined the main pathways

involved.

Materials and methods

Animals and drugs

The present study was performed in accordance with

the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (http://www.nicpbp.org.cn) for the Use of Laboratory

Animals and was approved by the Tongji Hospital of Tongji

University (Shanghai, China) Committee on Animal Care. A total of

30 male eight-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Experimental Animal

Center, Tongji University) weighing between 260 and 280 g were

housed in diurnal lighting conditions (12 h light/12 h dark;

22–24°C) and allowed free access to food and water for 7 days prior

to performing the investigation. GSRg3 (purity>98%; Fig. 1) was purchased from the National

Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products

(Beijing, China).

MI/R procedure in the rat hearts

The cardial MI/R surgery was performed, as described

previously (5). Briefly, the rats

were anaesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital

sodium (60 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)

and were placed on a warm board (25°C) to control the body

temperature at 37°C for surgery. The neck was opened with a ventral

midline incision and the animals were ventilated with room air

using a rodent respirator (tidal volume 8 ml/kg body weight; 60–80

breaths/min; Shanghai Alcott Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

An electrocardiogram in lead II was recorded through needle

electrodes attached to the limbs. Following the adjustment of the

respiratory rate and the tidal volume of gases, the chest was

opened by a middle thoracotomy. Following pericardiotomy, a 4-0

black silk thread (Millar, Inc., Houston, TX, USA) was passed

behind the left anterior descending coronary artery and was

occluded by a knot for 30 min to cause ischemia. Subsequently, the

knot was released and reperfusion was performed for 3 h. For the

sham control group, the black silk was placed under the left

anterior descending coronary artery without occlusion.

Hemodynamic measurements

The right common carotid artery was exposed and

cannulated with a Millar vessel (Millar, Inc.) into the left

ventricular cavity of the rat through the ascending aorta. The

heart function, including the left ventricular systolic pressure

(LVSP), heart rate (HR) and first derivative (±dp/dt) of left

ventricular pressure of the rats in each group (sham, I/R and

I/R+Rg3) were recorded and programmed using a biotic signal

collection and processing system (PowerLab; AD Instruments, New

South Wales, Australia), as described previously (6).

Determination of the serum levels of SOD,

LDH and CK

Following 3 h reperfusion, blood samples (5 ml) were

collected through the ventral aorta using a scalp vein set, and the

serum was frozen at −80°C until subsequent analysis. The activities

of LDH, CK and SOD were determined using an ELISA kit, according to

manufacturer’s instructions (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA,

USA).

Infarct size measurement

Following reperfusion, the hearts were rapidly

extracted from the rats using surgical scissors and frozen at

−20°C. The left ventricular area was sliced into six 2–3 mm-thick

slices perpendicular to the base-apex and incubated in 2%

triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; pH 7.4; Xiya Reagent, Chengdu,

China) buffer for 15 min at 37°C. The viable tissues were stained

dark red with TTC, while the infarcted portion remained

grayish-white. The area of infraction was measured using an image

analysis system [National Institutes of Health (NIH) image

software, version 1.60; NIH, Bethesda, MA, USA]

Isolation of primary neonatal rat

cardiomyocytes (NRCs) and anoxia-reoxygenation injury

Primary neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (1–3 days-old)

were purchased from the experimental Animal center of Tongji

University (Shanghai, China). Cardiac myocytes were cultured from

1–3 day-old Sprague-Dawley rats with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s

medium (DMEM; Gibco Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a

density of 5×105 for three days, as described previously

(1,2). The primary neonatal rats were

anaesthetized with sodium pentobartbital and decapitated, and then

immersed in 75% ethanol (20 ml) for 30 sec. The chest was opened

and the heart ventricles were dissected rapidly and immersed in

ice-cold Krebs-Ringer buffer containing 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM

CaCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.1 mM

MgCl2·6H2O, 0.4 mM

NaH2PO4·2H2O, 11.9 mM

NaHCO3 and 5.6 mM glucose (pH 7.4), and the ventricles

were minced into small sections using eye scissors and digested

with trypsin (0.1%; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Guangzhou,

China). The cardiomyocytes were cultured in DMEM containing 10%

newborn calf serum (NCS; Gibco Life Technologies), in a humidified

atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. The neonatal

rat cardiomyocytes (NRCs) were used and the ginsenoside-Rg3 and

solvent were preincubated with cells for 30 min prior to I/R

injury.

Simulated I/R (SI/R) was performed, as described

previously (1,2). Briefly, simulated ischemia buffer,

containing 98.5 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM

CaCl2, 40 mM sodium lactate and 20 mM HEPES (pH 6.8),

and simulated reoxygenation buffer, containing 20 mM

HCO3, 0.9 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM

CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM KCl,

129.5 mM NaCl and 5.5 mM glucose (pH 7.4), were prepared in

advance. The medium of the NRCs was replaced with 1 ml simulated

ischemia buffer, incubated in a hypoxic chamber (humidified

atmosphere 5% CO2/0% O2 balanced with

N2 at 37°C) for 3 h, and then reoxygenated in a standard

incubator for 2 h with reoxygenation buffer. The cells subjected to

control conditions were cultured with normal Tyrode solution (pH

7.4; Beijing Leagene Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) in a

humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/21% O2

balanced with N2 at 37°C for 5 h (4). The cells were divided randomly into

four groups: Control group, incubated with Tyrode solution during

the entire experimental period; SI/R group, incubated with

simulated ischemia buffer for 3 h hypoxia, followed by 2 h

re-oxygenation; Vehicle group, subjected to 0.2% (v/v) dimethyl

sulfoxide administration 30 min prior to SI/R; SI/R+GSRg3 group,

subjected to GSRg3 (10 mM) administration 30 min prior to SI/R

(5).

Cell viability

The cell viability was assessed using a Cell

Counting Assay kit-8 (CCK-8, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The NRCs (100

μl) were plated into 96-well plates at a density of

1×105 cells/well, followed by 30 min pre-incubation with

different concentrations of GSRg3 (0.1–100 μM). Following

treatment, the cells were exposed to 10 μl CCK-8 solution

for a futher 2 h and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a

microplate reader (ELx808; Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA)

(1).

Determination of apoptosis by flow

cytometry

The apoptotic rate of the NRCs was determined by

flow cytometry using annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) staining according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the NRCs were pretreated with

10 μM GSRg3 for 30 min followed by SI/R treatment. The cells

were digested with trypsin (0.25%) and were then resuspended in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% NCS. The cells were

centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 min at 4°C and then washed twice with

cold PBS. The cells were then treated with 5 μl annexin

V-FITC (1:80) and 10 μl PI (1:40) (Bioworld Technology Co.,

Ltd., Nanjing, China), and incubated in the dark at room

temperature for 15 min. Each sample was analyzed using a

Beckton-Dickinson flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes,

NJ, USA).

Western blot analysis

The NRCs were lysed in lysis buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail

(Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 30 min on ice. The

cellular proteins were collected using a cell scraper. Following

centrifugation for 15 min at 12,000 rpm, a Bicinchoninic acid

Protein Assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to

determine the protein concentrations. Equal quantities of protein

were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA,

USA). The membranes were blocked using 5% non-fat milk in

Tris-buffered saline (8 g NaCl and 6 g Tris), containing 1%

Tween-20 (TBST), for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were

then incubated with primary antibodies against eNOS (610297; IgG1;

polyclonal; 1:3,000; BD Biosciences), p-Akt (2920; mouse

monoclonal; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA,

USA), Akt (4691; rabbit monoclonal; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) Bcl-2 (2870; mouse poly-clonal; 1:10000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), Bax (2772; mouse polyclonal; 1:2,000;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and PARP (5625; rabbit monoclonal;

1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C.

Following washing three times for 5 min with TBST, the membranes

were incubated with secondary antibodies, including alkaline

phosphatase-linked anti-mouse (7056; IgG; 1:5,000; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) or horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit

antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. β-actin (7074; IgG;

1:5,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) was used as an internal

control. The protein bands were visualized using a

Chemiluminescence Electophoretic Mobility Shift Assay kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) and X-ray film (Kodak BioMax MS Film;

Kodak. Corp., Rochester, NY, USA). The band density was

statistically analyzed using Image J software (National Institutes

of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of

the mean. The statistical comparisons between groups were performed

using one-way analysis of variance. SPSS version 19.0 was used to

perform all statistical analyses (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Effect of GSRg3 on cardiac function

GSRg3 had no effect on blood glucose, cardiac

function or blood pressure normality and no significant differences

were observed between the groups at the baseline conditions.

Pretreatment with GSRg3 increased LVSP and +dp/dt max, and

decreased LVEDP and −dp/dt max following 3 h reperfusion, compared

with the MI/R group (P<0.05; Fig.

2). Treatment with GSRd markedly increased the mean heart rate

compared with the MI/R group (P<0.05; Fig. 3). The hemodynamic data demonstrated

that GSRg3 improved rat cardiac systolic and diastolic function

following MI/R.

| Figure 2GSRg3 improves rat cardiac function

following 30 min ischemia and 3 h reperfusion. Improvements were

observed in (A) LVSP, (B) LVEDP, (C) +dP/dt max and (D) −dP/dt max.

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=8;

*P<0.05, vs. sham, #P<0.05 and

##P<0.01, vs. I/R). LVSP, left ventricular systolic

pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure; ±dP/dt

max, instantaneous first derivation of left ventricle pressure;

sham, untreated; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; I/R+Rg3, I/R+Rg3

administration 3 days prior to surgery; baseline, immediately

following stabilization; I0, pre-ischemic treatment; R0, start of

reperfusion; R30, 30 min after reperfusion; R60, 60 min after

reperfusion; R180, 180 min after reperfusion. GSRg3, ginsenoside

Rg3. |

| Figure 3Changes in heart rate. Data are

expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=8;

*P<0.05, vs. sham, #P<0.05, vs. I/R).

Sham, no treatment, I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; I/R+Rg3, I/R+Rg3

treatment 3 days prior to experimental surgery; baseline,

immediately after stabilization; I0, pre-ischemic treatment; R0,

start of reperfusion; R30, 30 min after reperfusion; R60, 60 min

after reperfusion; R180, 180 min after reperfusion; GSRg3,

ginsenoside Rg3. |

GSRg3 reduced rat myocardial injury

(infarct size, necrosis, and apoptosis) post MI/R

The infacted areas and areas at risk are shown in

Fig. 4. No MI was observed in the

hearts from the sham group. Pretreatment with GSRg3 significantly

decreased the infarct size compared with the MI/R group

(P<0.05). To determine whether GSRg3 attenuated MI/R induced

cardio-myocyte necrosis, the plasma levels of CK, LDH and SOD were

measured following reperfusion. GSRg3 treatment markedly decreased

the levels of CK and LDH, and increased the levels of SOD compared

with the MI/R group (P<0.05). These data demonstrated that GSRg3

reduced myocardial necrosis following MI/R.

| Figure 4GSRg3 reduces rat myocardial injury

(infarct size, necrosis, and apoptosis) post I/R. (A) INF in rats

subjected to 30 min I, followed by 3 h R. Red-staining represents

the AAR and pale areas indicate infracted regions. INF is expressed

as a percentage of the AAR. (B) Plasma CK levels. (C) Plasma LDH

levels. (D) Plasma SOD levels. Data are expressed as the mean ±

standard error of the mean (n=6; *P<0.05, vs. I/R,

#P<0.05, vs. sham). I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; INF,

myocardial infract size; AAR, area at risk; CK, creatine kinase;

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSRg3,

ginsenoside Rg3. |

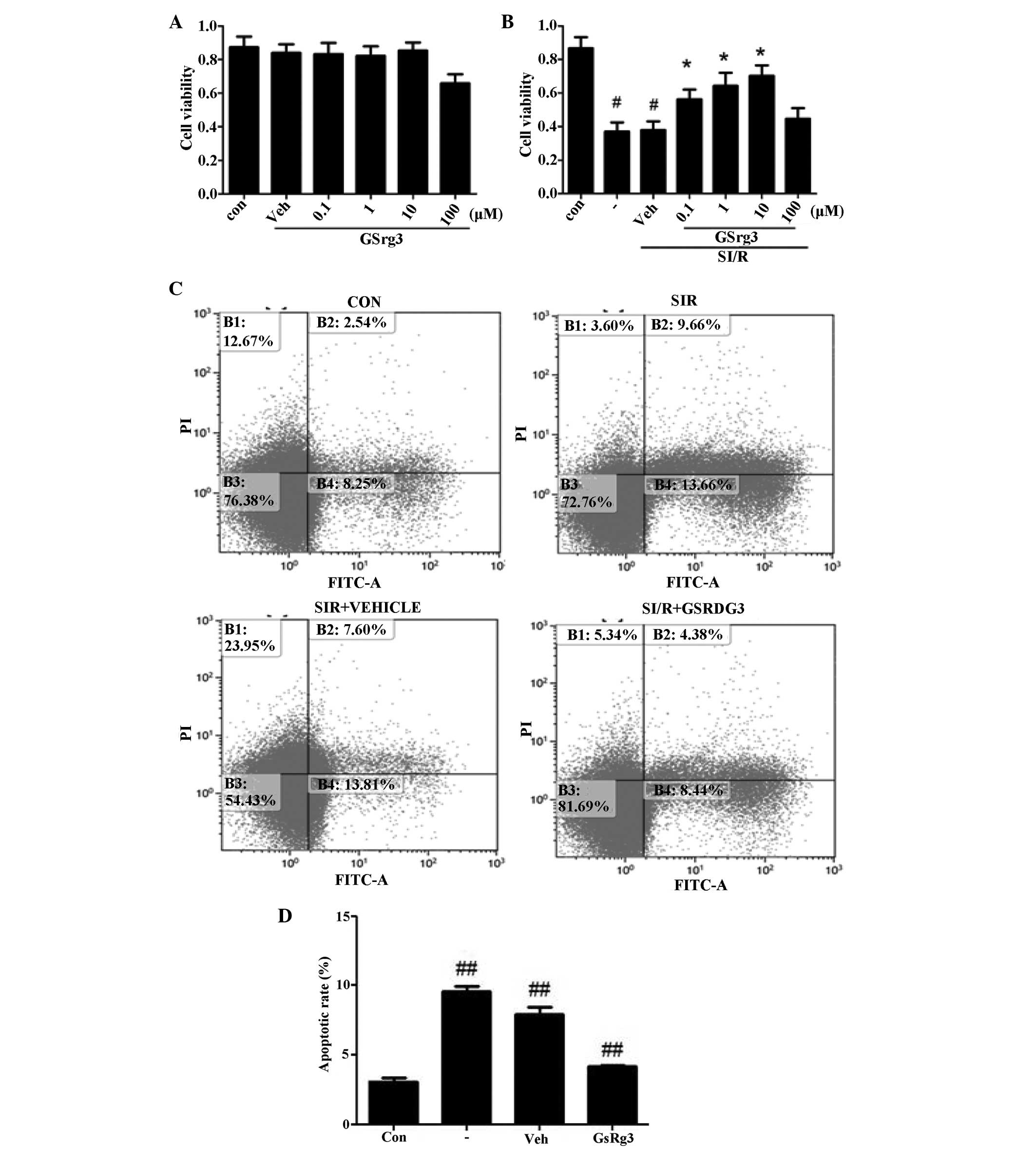

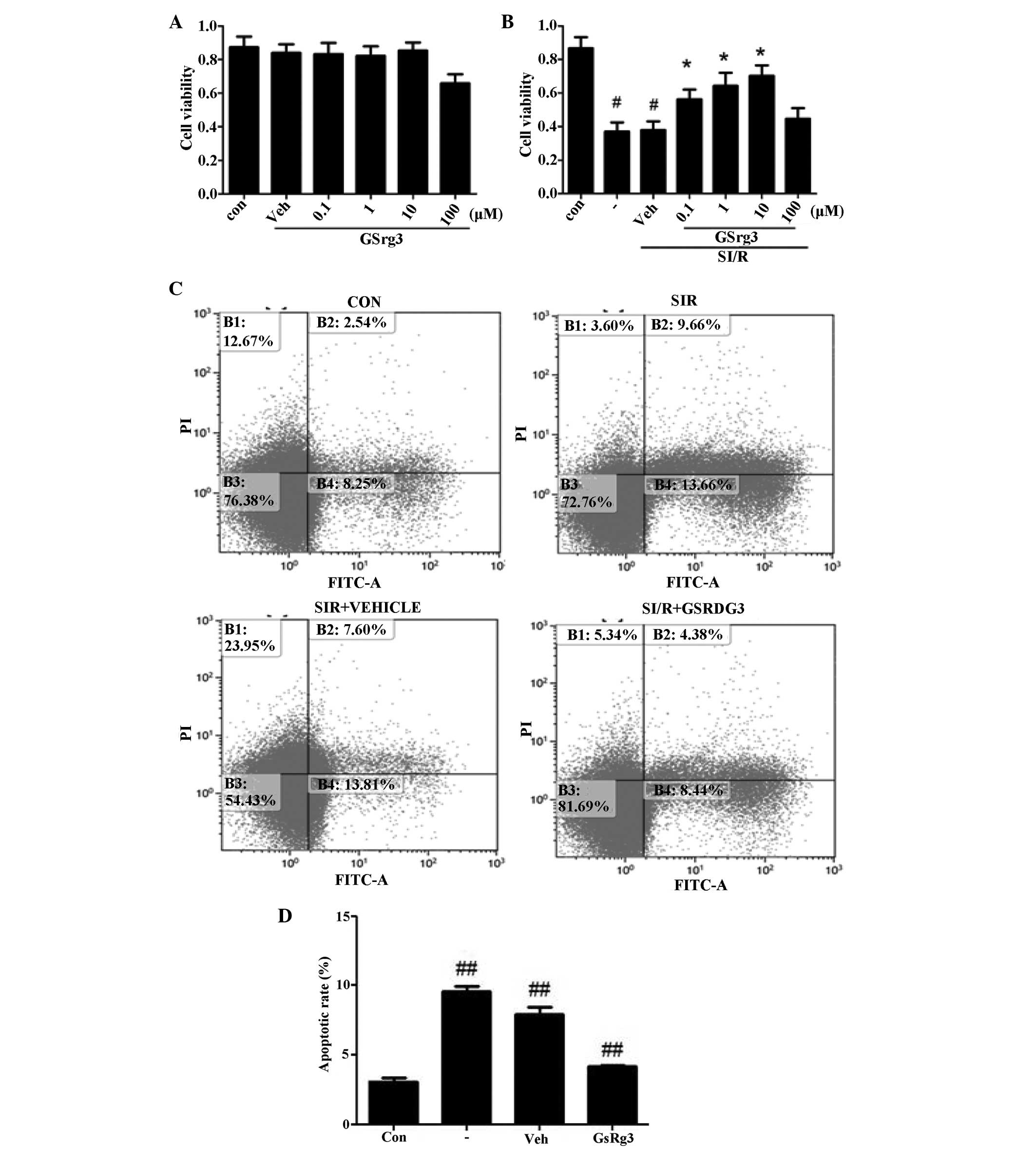

GSRg3 improves SI/R-induced in vitro cell

injury, increasing viability and decreasing apoptosis

The NRCs were treated with different concentrations

of GSRg3 (0.1–100 mM) to determine the effects of GSRg3 alone.

Treatment with these concentrations of GSRg3 for 24 h were not

cytotoxic, as demonstrated by the CCK-8 assay (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, the concentration response curves

determined cellular viability, and this was observed at dosage of

10 mM GSRg3.

| Figure 5GSRg3 improves SI/R-induced in

vitro cell injury (viability and apoptosis). (A) GSRg3

treatment alone (0.1–100 μM) for 24 h had no effect on NRC

viability, suggesting that no GSRg3-induced toxicity occurred at

concentrations up to 10 μM (n=8; *P<0.05, vs.

control). (B) Cellular viability was determined using an MTT assay

following SI/R (3 h hypoxia followed by 2 h reoxygenation). (C)

SI/R-induced apoptosis was determined by annexin V-FITC/PI flow

cytometry in control and vehicle groups. (D) GSRg3 (10 mM)

significantly reduced SI/R-induced apoptosis as determined by

annexin V-FITC/PI flow cytometry. Data are expressed as the mean ±

standard error of the mean (#P<0.05 and

##P<0.01, vs. control; *P<0.01, vs.

SI/R.) These experiments were performed in triplicate with similar

results. SI/R, simulated ischemia/reperfusion; GSRg3, ginsenoside

Rg3; NRC, neonatal rat cardiomyocyte; FITC, fluorescein

isothiocyanate; PI, propidium iodide; Con, control; Veh, vehicle

(0.2% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide treatment 30 min prior to SI/R). |

Flow cytometric analysis was perfomed to assess the

cellular apoptosis (Fig. 5C).

Annexin V/PI double staining revealed a significant increase in

apoptosis in the sham group compared with the control post-SI/R

(8.6±0.3%, vs. 3.1±0.2%; P<0.05), and treatment with 10 mM GSRg3

markedly decreased cellular apoptosis (4.6±0.1%; P<0.01;

Fig. 5D). Overall, these in

vitro results suggested that GSRg3 protected cardiomyocytes,

which was in accordance with the in vivo data.

GSRg3 modulates the expression levels of

Bcl-2 and Bax in NRCs subjected to SI/R

The present study aimed to determine whether GSRg3

inhibited the apoptosis of NRCs induced by SI/R by modulating the

Bcl-2 family proteins. SI/R treatment reduced the expression of

Bcl-2 and increased the expression of Bax, therefore,

downregulating the Bcl-2/Bax ratio (Fig. 6A). Pretreating NRCs with 10 mM

GsRg3 prior to SI/R induced the expression of Bcl-2 and inhibited

the expression of Bax, therefore, increasing the Bcl-2/Bax ratio

(Fig. 6A).

| Figure 6GSRg3 inhibits mitochondrial-mediated

apoptosis in NRCs subjected to SI/R. (A) Representative western

blot analysis demonstrating the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax

following various treatments. Densitometric analysis demonstrated

that SI/R reduced the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax, however, treatment with

GSRg3 increased the Bcl-2/Bax ratio. (B) Representative western

blot analysis of the SI/R-induced activation of caspase-3 and

caspase-9. Densitometric analysis demonstrated that 10 mM GSRg3

reduced the expression levels of cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3.

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=6;

##P<0.01, vs. control, #P<0.05 and

**P<0.01, vs. SI/R.) SI/R, simulated

ischemia/reperfusion; GSRg3, ginsenoside Rg3; NRC, neonatal rat

cardiomyocyte; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; Bax, Bcl-2 associated X

protein; Con, control; Veh, vehicle (0.2% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide

treatment 30 min prior to SI/R). |

GSRg3 decreases the activities of

caspase-3 and caspase-9 in NRCs following SI/R

The caspase family of proteins regulate cellular

apoptosis. Caspase-9 is activated by cytochrome c, which

activates caspase-3, causing cell apoptosis (4). SI/R significantly increased the

protein expression levels of cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3,

however, pretreating NRCs with 10 mM GsRg3 significantly attenuated

the expression levels of cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Fig. 6B).

GSRg3 increases the phosphorylation of

Akt and eNOS in NRCs subjected to SI/R

To further investigate the molecular mechanism

underlying GsRg3-mediated cardioprotection, western blot analysis

was performed to determine the protein expression levels of

phosphorylated (p)-Akt/Akt and p-eNOS in NRCs following SI/R. No

significant differences were observed in the expression levels of

Akt and eNOS between the treatment groups at the baseline (Fig. 7A and B). Consistent with previous

reports, pretreatment with 10 mM GSRg3 significantly increased the

expression levels of p-Akt and p-eNOS, and consequently increased

the ratios of p-Akt/Akt and p-eNOS/eNOS (P<0.01). Treatment with

the phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, LY294002, inhibited the

GSRg3-mediated phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 7B).

| Figure 7GSRg3 increases the phosphorylation of

Akt and eNOS in NRCs subjected to SI/R. Densitometric analysis

demonstrated that GSRg3 increased the ratio of (A) p-eNOS/eNOS and

(B) p-Akt/Akt, and the increasing ratio of p-Akt/Akt was

significantly inhibited by the Akt inhibitor, LY294002. Data are

expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=6;

#P<0.05 and ##P<0.05, vs. SI/R;

*P<0.01, vs. SI/R+GSRg3.) SI/R, simulated

ischemia/reperfusion; GSRg3, ginsenoside Rg3; NRC, neonatal rat

cardiomyocyte; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; Con,

control; Veh, vehicle(0.2% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide treatment 30

min prior to SI/R); p, phosphorylated. |

Discussion

The present study revealed that GSRg3 significantly

attenuated MI/R injury in the rat model, as demonstrated by the

reduced myocardial infarct size, improved rat cardiac functions,

CK/LDH levels in blood following MI/R and decreased NRC apoptosis.

The in vitro investigation revealed that treatment with

GSRg3 (10 mM) reduced the NRC apoptotic response by inhibiting the

activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 and by increasing the

phosphorylation of Akt/eNOS and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio.

As one of the most popular Chinese herbal medicines,

ginseng has been used for the treatment of diabetes, cancer and

cardiovascular diseases for thousands of years (7,8).

Over 40 ginsenosides have been isolated and identified (9). Previous studies have demonstrated

that ginsenosides exerts significant protective effects on the

cardiovascular system (9–11). MI/R injury is predominantly caused

by ardiomyocyte apoptosis (12)

and GSRg3 is able to directly depress cardiomyocytes contraction by

increasing the production of nitric oxide (NO) (13). Yang et al demonstrated that

the NO produced by eNOS has a direct impact on cardiac remodeling

(14). In addition, it has also

been suggested that GSRg1 is important in the improvement of the

cardiovascular system. In a tumor necrosis factor-α stimulated

HUVEsl culture model, GSRg1 increases the production of NO and the

mRNA expression of eNOS (15).

In vitro, GSRg1 is capable of reducing homocysteine-induced

endothelial dysfunction and free radical production in porcine

coronary arteries (16–18). Therefore, the present study aimed

to determine whether pretreatment with GSRg1 reduced myocardial

infarction following MI/R, and whether this had significant

clinical importance. A previous study suggested that GSRg1 may

induce the production of NO and regulate the acute activation of

eNOS in human aortic endothelial cells (19).

GSRg3, an important ginsenoside in the extract of

ginseng, is used in herbal medicine as a tonic and restorative

agent. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the beneficial

effects of GSRg3 remains to be elucidated. The present study

demonstrated, using an in vivo rat model, that pretreatment

with GSRg3 significantly decreased the infarct size and plasma

levels of CK/LDH. The levels of CK/LDH and oxidative stress in the

myocardium were also significantly suppressed in the GSRg3 treated

group, whereas the level of SOD was improved. In vitro, SI/R

treatment increased the expression of Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein,

decreased the expression of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein,

reduced the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and activated caspase-3 and caspase-9.

GSRg3 upregulated the phosphorylation of eNOS and increased the

expression of p-Akt.

In conclusion, GSRg3 exerted cardioprotective

effects in MI/R injury and may have a positive significance for

clinical treatment.

References

|

1

|

Terman A and Brunk UT: The effect of

Polbax extract on lipofuscin accumulation in cultured neonatal rat

cardiac myocytes. Phytother Res. 16:180–182. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chlopcíková S, Psotová J, Miketová P,

Sousek J, Lichnovský V and Simánek V: Chemoprotective effect of

plant phenolics against anthracycline-induced toxicity on rat

cardiomyocytes. Part II caffeic, chlorogenic and rosmarinic acids.

Phytother Res. 18:408–413. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Li SY, Wang XG, Ma MM, Liu Y, Du YH, et

al: Ginsenoside-Rd potentiates apoptosis induced by hydrogen

peroxide in basilar artery smooth muscle cells through the

mitochondrial pathway. Apoptosis. 17:113–120. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang Y, Li X, Wang X, Gao F, et al:

Ginsenoside Rd attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury

via Akt/GSK-3β signaling and inhibition of the

mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway. PLoS One. 8:e709562013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhu JH, Qiu YG, Wang QQ, Zhu YJ, Hu SJ,

Zheng LG, et al: Low dose cyclophosphamide rescues myocardial

function from ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Eur J Cardiothorac

Surg. 34:661–666. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li C, Gao Y, Tian J, Shen J, Xing Y, Liu

Z, et al: Sophocarpine administration preserves myocardial function

from ischemia-reperfusion in rats via NF-κB inactivation. J

Ethnopharmacol. 135:620–625. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chang YS, Seo EK, Gyllenhaal C and Block

KI: Panax ginseng: a role in cancer therapy? Integr Cancer Ther.

2:13–33. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Attele AS, Zhou, Yuan CS, et al:

Antidiabetic effects of Panax ginseng berry extract and the

identification of an effective component. Diabetes. 51:1851–1858.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shi Y, Han B, Yu X, Qu S and Sui D:

Ginsenoside Rb3 ameliorates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury

in rats. Pharm Biol. 49:900–906. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Peng L, Sun S, Xie LH, Wicks SM and Xie

JT: Ginsenoside Re: pharmacological effects on cardiovascular

system. Cardiovasc Ther. 30:e183–188. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xia R, Zhao B, Wu Y, Hou JB, Zhang L, et

al: Ginsenoside Rb1 preconditioning enhances eNOS expression and

attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats.

J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011:7679302011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ji L, Fu F, Zhang L, Liu W, Cai X, et al:

Insulin attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via

reducing oxidative/nitrative stress. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

298:871–880. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Scott GI, Colligan PB, Ren BH and Ren J:

Ginsenosides Rb1 and Re decrease cardiac contraction in adult rat

ventricular myocytes: role of nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol.

134:1159–1165. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang XP, Liu YH, Shesely EG, Bulagannawar

M, Liu F and Carretero OA: Endothelial nitric oxide gene knockout

mice: cardiac phenotypes and the effect of angiotensinconverting

enzyme inhibitor on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Hypertension. 34:24–30. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lü JP, Ma ZC, Yang J, Huang J, Wang SR and

Wang SQ: Ginsenoside Rg1-induced alterations in gene expression in

TNF-α-stimulated endothelial cells. Chin Med J (Engl). 117:871–876.

2004.

|

|

16

|

Zhou W, Chai H, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q

and Chen C: Ginsenoside Rb1 blocks homocysteine-induced endothelial

dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 41:861–868.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fu W, Conklin BS, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao

Q and Chen C: Red wine prevents homocysteine-induced endothelial

dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Surg Res. 115:82–91.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Spencer TA, Chai H, Fu W, et al: Estrogen

blocks homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine

coronary arteries (1,2). J Surg Res. 118:83–90. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yu J, Eto M, Akishita M, Kaneko A, Ouchi Y

and Okabe T: Signaling pathway of nitric oxide production induced

by ginsenoside Rb1 in human aortic endothelial cells: a possible

involvement of androgen receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

353:764–769. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|