Introduction

Glycosylation of proteins is the most important

posttranslational modification in eukaryotes. Changes in

glycosylation patterns are known to occur during cancer formation

and progression (1–3). These changes influence cellular

functions including cell adhesion and cell immunogenicity (4,5), and

facilitate the generation of remote metastases (1). These effects predominantly occur from

changes in gene expression levels of glycosyltransferases (GTs),

which are often regulated by oncogenes (6,7).

Hence, conclusive studies using cancer cell lines and primary

tumours (4) have suggested that

the gene expression patterns of glycosyltransferases may serve as a

prognostic marker in patients with cancer (8,9).

Circulating tumour cells (CTCs) are cells that

dissociate from primary epithelial tumours, circulate through blood

stream and lymphatic vessels and are the predominant cause of

remote metastasis (10–12). All these abilities can reportedly

be regulated by glycosylation and therefore establish a strong

association to altered glycosylation (13). It is hypothesized that CTCs show

different glycosyltransferase (GT) gene expression levels not only

in comparison to normal epithelial cells, but also in comparison to

surrounding blood cells. This hypothesis therefore suggests that

CTCs may be detected and analyzed by quantitative polymerase chain

reaction and in a further step might also open roads towards

characterizing CTCs by GT gene expression levels.

The present study first analyzed the gene expression

levels of six GT genes including: N-acetylgalactosaminyl

transferase 6 (GALNT6), N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase V

(MGAT5B), ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 1 (ST3GAL1),

fucosyl transferase 3 (FUT3), ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyl

transferase 3 (ST3GAL3) and ST6 (α-N-acetyl-neuraminyl-2,3-β-galac

tosyl-1,3)-N-acetylgalactosaminide α-2,6-sialyltransferase 1

(ST6GALNac1) in blood samples of healthy donors that had been

inoculated with different numbers of breast cancer cells.

The studied genes were selected due to the following

associations with breast cancer: GALNT6 is involved in the

fibronectin pathway and is responsible for breast tumour

development and progression (14);

MGAT5B has been reported to function in cell motility and

metastasis formation (1,5); ST3GAL1 was found to be increasingly

expressed in primary breast carcinoma cells and may be correlated

to histological grade (15); FUT3

is an effector of metastasis in hormone receptor dependent breast

cancers (16); ST3GAL3 is known to

be correlated with tumour size and number of affected lymph nodes

(9); and ST6GALNac1 is associated

with ductal carcinomas and patients with an elevated expression of

ST6GALNac1 have a better prognosis for survival (17).

After establishing a model system, the three best

performing genes in the primary blood samples of 20 patients with

adjuvant breast cancer were compared to 20 healthy donors. The

differences in expression levels of the two groups were analysed

and correlated to GT gene expression levels with tumour

characteristics.

Materials and methods

Blood samples

All patients enrolled in the present study provided

a written informed consent and the research was performed in

compliance with the Helsinki Declaration (ethical vote 148-12). A

total of 20 ml blood was obtained from 20 patients with adjuvant

breast cancer and from healthy donors in EDTA-tubes to prevent

early coagulation. As a standard, all samples, from adjuvant breast

cancer patients as well as from healthy donors with or without

inoculation, were treated in the same manner including the

subsequent reverse transcription and quantitative PCR reactions.

The blood samples were subjected to density gradient centrifugation

(400 × g, 30 min); the buffy-coat solutions were discarded and the

harvested cell pellets were washed twice with phosphate-buffered

saline (Biochrom GmBH, Berlin, Germany) and centrifugation (250 ×

g, 10 min). After discarding surplus supernatant, the cell pellets

were air-dried and stored at −80°C until further use.

Cell lines

Cama-1 (HTB-21; mammary gland adenocarcinoma), MCF-7

(57136; mammary gland adenocarcinoma) and ZR-75-1 (CRL-1500; ductal

carcinoma) breast cancer cell lines were obtained from the American

Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and sub-cultured

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After a detachment

step with trypsin (Biochrom GmBH), the cells were counted with a

hematocytometer and added to the blood samples in predefined

numbers (10 cells/ml blood, 100 cells/ml blood, 1,000 cells/ml

blood).

RNA extraction

Blood cell pellets were thawed and dissolved in 1 ml

TRIzol® (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Darmstadt,

Germany). For innoculation experiments, the breast cancer cells

were subsequently added following TRIzol treatment, in order to

prevent immunologic effects. Subsequently, 0.2 ml chloroform (Merck

Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was added and the suspension was

vigorously mixed before centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at

4°C. The clear liquid phase was aspired and 1 ml isopropanol (Merck

Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was added. The solution was stored

overnight at −20°C to precipitate the RNA. On the following day,

the solution was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the

supernatant was carefully removed and the RNA pellet was washed

twice with 75% ethanol (Merck Millipore) by centrifugation at

12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The RNA-pellet was dried, resolved in

20 μl DEPC-treated water and stored at −20°C until further

use. To control the RNA quantity and quality, the concentration was

measured using a Nano-photometer (Implen GmbH, Munich, Germany) and

denaturing formaldehyde gel electrophoresis was performed.

Reverse transcription

Reverse transcription was performed using

SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis Super Mix (Invitrogen Life

Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A

total of 4 μg RNA was used for a single reverse

transcription reaction.

Quantitative PCR

For quantitative PCR, TaqMan® Fast

Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies,

Foster City, CA, USA) was used. For each gene, a reaction mix

consisting of 10 μl Master Mix, 7 μl H2O

and 1 μl TaqMan Primer (GALNT6: Hs_00200529_m1, MGAT5B:

Hs_01586300_m1, ST3GAL1: Hs_00161688_m1, FUT3: Hs_00356857_m1,

ST3GAL3: Hs_00544033_m1, ST6GALNac1: Hs_00300842_m1) was prepared

and added to 2 μl cDNA in a 96-well plate (Micro

Amp® Fast Optical 96-Well Reaction Plate with Barcode;

Applied Biosystems Life Technologies), which was then sealed with

an adhesive cover and analysed in a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR machine

(Applied Biosystems Life Technologies). Each gene was analysed as

quadruplicate. The PCR cycles were run as follows: initial

denaturation (95°C for 20 s), followed by 40 cycles with

denaturation (3 s at 95°C) and primer extension (30 s at 60°C). The

fluorescence for each gene was displayed by the SDS 1.3.1 software

(Applied Biosystems Life Technologies).

Evaluation

The SDS software performed an automatic calculation

of CT-, ΔCT-, ΔΔCT- and relative quantification (RQ) values

(18). The resulting files were

exported to Microsoft® Excel™(Microsoft Corporation,

Redmond, WA, USA) and graphs were generated. Statistical

evaluations were performed by using SPSS version 21.0

(International Business Machines Corporation, Ehningen, Germany).

For patient samples and negative control samples, the average RQ

value of all 20 samples was calculated including the “not

detected”-samples, using “0” as replacement character.

Results

RQ-values of glycosyltransferase genes in

blood inoculation experiments

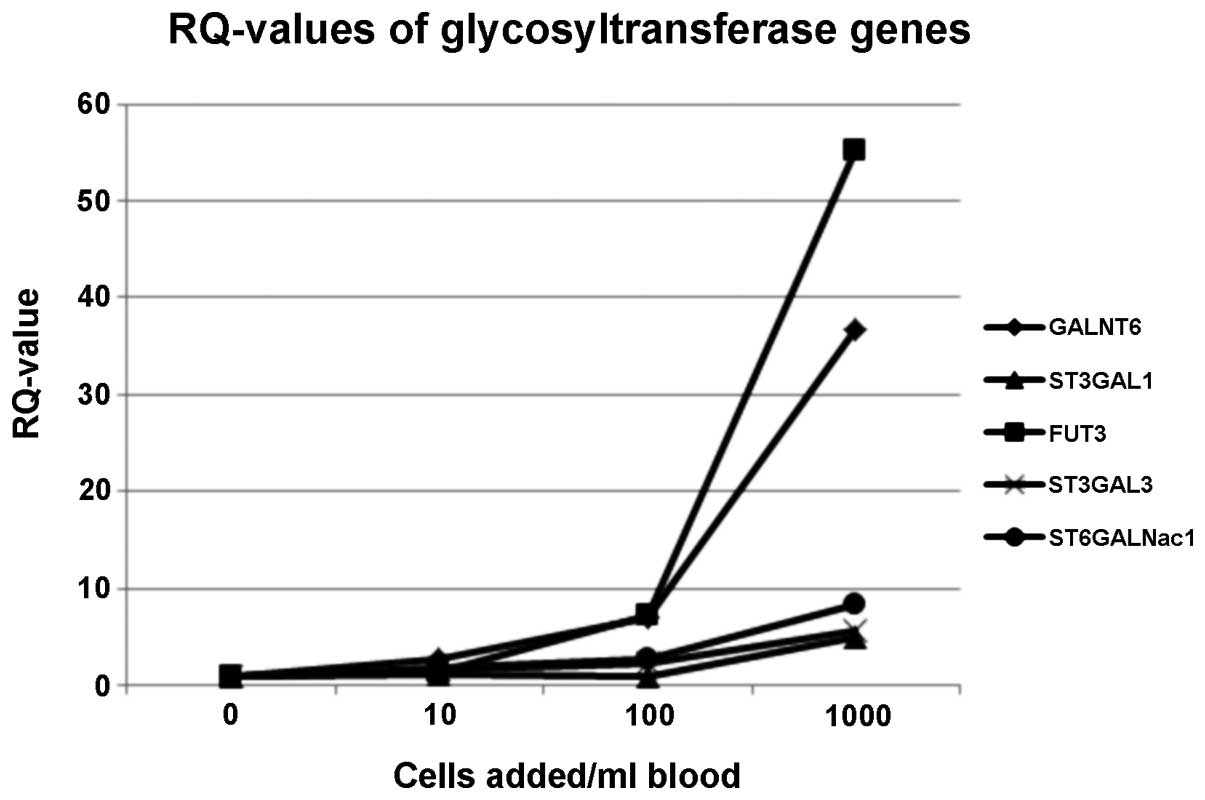

The RQ curves showed that 5/6 analysed GT genes

could be used for CTC-detection. Only one gene (MGAT5B) was

expressed at low levels such that it was not detected by

quantitative PCR. FUT3 and GALNT6 exhibited the highest RQ-values,

which indicated that they maybe suitable genes for CTC detection

from blood samples. Gene expression levels of ST3GAL3 and

ST6GALNac1 also increased from the 10-cells/ml blood sample on, but

underperformed in the logarithmic model system. The only gene for

which the RQ-values markedly increased from the 100-cells/ml blood

on was ST3GAL1 (Fig. 1).

Statistical evaluation of inoculation

experiments

Increases in gene expression were analysed

statistically for each gene and every concentration of added breast

cancer cells. ΔCt-values were used for analysis. In a two-tailed

T-test, the ΔCt-values of the reference sample without addition of

tumour cells were compared to the samples where 10, 100 and 1,000

breast cancer cells had been added. The results of these statistics

are shown in Table I. Regarding

the statistical evaluation, the best gene for CTC-detection, with

significantly different ΔCt-values from the 10-cell level on is

GALNT6 (P=0.0023). Accordingly, GALNT6 P-values for the 100- and

1000- cell samples were significantly different from the reference

sample and revealed the highest P-values of all examined genes

(P=1.3×10−5 and P=3.8×10−7, respectively).

ST3GAL3 and ST6GALNac1 exhibited borderline significantly different

ΔCt-values at the 10-cell level (P=0.0051 and P=0.0097), and the

values for the 100- and 1,000 cell samples for these two genes were

significantly different from the reference sample

(P=4.9×10−5 and 1.3×10−6 for ST3GAL3 and

0.0039 and 1×10−4 for ST6GALNac1). The ΔCt-values of

FUT3 showed a significant difference to the 0-cell sample from the

100-cell level (P=0.027 and P=0.0018 for 1000 cells added to the

blood sample), whereas the 10-cell sample showed no difference to

the sample without addition of tumour cells (P=0.553). ST3GAL1 was

only significantly different in ΔCt-value for the 1000-cell sample

(P=0.0013). The other two values did not reach significance

(P=0.5918 for 10 breast cancer cells added and P=0.684 for 100

breast cancer cells).

| Table IStatistical comparison of ΔCt values

of glycosyltransferase genes between samples without addition of

breast cancer cells and samples containing 10, 100, or 1,000 tumour

cells. |

Table I

Statistical comparison of ΔCt values

of glycosyltransferase genes between samples without addition of

breast cancer cells and samples containing 10, 100, or 1,000 tumour

cells.

| Δ Ct comparison | P-value

|

|---|

| GALNT6 | MGAT5B | ST3GAL1 | FUT3 | ST3GAL3 | ST6GALNac1 |

|---|

| 0 vs. 10 cells | 0.0023 | nd | 0.5918 | 0.553 | 0.0051 | 0.097 |

| 0 vs. 100 cells |

1.3×10−5 | nd | 0.684 | 0.027 |

4.9×10−5 | 0.0039 |

| 0 vs. 1,000

cells |

3.8×10−7 | nd | 0.0013 | 0.0018 |

1.3×10−6 |

1.0×10−4 |

RQ-values of adjuvant breast cancer

patient samples vs. negative control samples

After establishing the model system, GALNT6, FUT3

and ST3GAL3 were selected to be analysed in the patient samples.

FUT3 expression was detected in five of the patients and seven of

the negative control samples, GALNT6 in 12 and 14 samples,

respectively, and ST3GAL3 was detectable in almost all patients

(n=19) and negative control (n=17) samples, by quantitative PCR.

Average RQ-values for each gene were calculated for the adjuvant

breast cancer patients as well as for the negative control group.

For the three genes analysed, the average RQ-values were higher

overall in the negative control sample group as compared with the

patient sample group. The highest average RQ-value divergence was

observed in FUT3 (Fig. 2).

Association of RQ-values with tumour

characteristics

The RQ-values of gene expression of the adjuvant

breast cancer samples were correlated to their tumour

characteristics. It was identified that in two patients (No. 6 and

15) all three gene expression values were upregulated (RQ-values

>1). In two further patients (No. 7 and 11), FUT3 and ST3GAL3

were upregulated in comparison to a healthy control sample

(Table II). However, significant

correlations of changes in gene expressions to age at primary

diagnosis, histological subtype, tumour size, nodal state, grading

or hormone- and Her-2 receptors, could not be generated from this

dataset.

| Table IIAssociation of relative quantification

(RQ)-values with patient/tumour characteristics. |

Table II

Association of relative quantification

(RQ)-values with patient/tumour characteristics.

| Patient number | Age (years) | Histological

subtype | Tumour size (mm) | Nodal stage | Grading | ER % | PR % | Her2 | FUT3 | GALNT6 | ST3GAL3 |

|---|

| 1 | 58 | Inv. duct. | 1b (11) | 1a | 2 | 100 | 50 | pos | n.d. | n.d. | 0.025 |

| 2 | 71 | Inv. duct. /

DCIS | 2 (27) | 1 | 2 | pos | pos | neg | n.d. | n.d. | 0.129 |

| 3 | 50 | Inv. duct. | 1c (12) | 0 | 3 | 90 | 100 | neg | n.d. | n.d. | 4.185 |

| 4 | 52 | Inv. duct. | 1c (18) | 0 | 2 | 90 | 30 | neg | n.d. | n.d. | 2.828 |

| 5 | 42 | Inv. duct. | 3 (58) | 0 | 3 | 75 | 0 | neg | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 6 | 48 | Inv. duct. | 1c (11) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | pos | 14.893 | 1.416 | 5.023 |

| 7 | 42 | Inv. duct. /

DCIS | 1 (1) | 1 | 2 | 90 | 1 | neg | 3.829 | 0.905 | 4.327 |

| 8 | 38 | Inv. duct. | 1b (8) | 0 | 2 | 100 | 30 | neg | n.d. | n.d. | 0.137 |

| 9 | 73 | Inv. duct. | 1c (12) | 1a | 2 | 90 | 90 | neg | n.d. | n.d. | 0.041 |

| 10 | 62 | Inv. lob. /

LIN | 2 (38) | 0 | 2 | 90 | 80 | neg | n.d. | n.d. | 0.037 |

| 11 | 69 | Inv. lob. | 1b (9) | 0 | 2 | 90 | 5 | neg | 1.271 | 0.210 | 1.365 |

| 12 | 56 | Inv. duct. | 1a (4) | 0 | 1 | 81 | 5 | neg | n.d. | 0.018 | 0.164 |

| 13 | 60 | Inv. lob. /

DCIS | 2 (40) | 1a | 2 | 90 | 30 | pos | n.d. | 0.043 | 0.093 |

| 14 | 54 | Inv. duct. /

DCIS | 1a (10) | 0 | 2 | 80 | 5 | pos | 1.481 | 0.052 | 0.168 |

| 15 | 58 | Inv. duct. | 1c (10) | 0 | 2 | 10 | 1 | neg | 5.538 | 1.194 | 4.785 |

| 16 | 73 | Inv. duct. | 2 (25) | 0 | 2 | 80 | 80 | neg | n.d. | 0.110 | 0.108 |

| 17 | 54 | Inv. duct. | 1c (13) | 0 | 1 | 100 | 100 | neg | n.d. | 0.213 | 1.863 |

| 18 | 51 | Inv. duct. /

lob. | 1c (19) | 1a | 2 | 90 | 90 | neg | n.d. | 0.101 | 0.082 |

| 19 | 33 | Inv. duct. | 2 (30) | 0 | 2 | 99 | 99 | pos | n.d. | 0.110 | 0.100 |

| 20 | 74 | Inv. duct. | 1c (25) | 0 | 2 | 99 | 99 | pos | n.d. | 0.470 | 0.499 |

Discussion

Altered glycosylation of membrane bound proteins is

a predominant feature of tumour cells that is necessary for cell

adhesion and detachment processes and facilitates immune escape of

malignant cells. Quantitative PCR-based techniques are already in

use for solid tumour profiling and are considered to be objective,

robust and cost-effective molecular techniques that could be used

in routine cancer diagnostics (19). The present study used a

Quantitative PCR assay for the detection of CTCs from peripheral

blood. This approach is advantageous for the patient, avoiding

painful and sometimes unsatisfactory procedures for biopsies or

bone marrow aspirations for analysis.

Glycosyl transferases are a new group of marker

genes for CTC-detection from blood samples of patients with breast

cancer. In the model system presented, increases in gene expression

of different glycosyl transferases were identified through

Quantitative PCR, with increasing numbers of breast cancer cells

that had been added to the blood sample of a healthy donor.

The inoculation of blood with breast cancer cells

identified FUT3 as the most suitable gene for CTC-detection.

Further statistical evaluation revealed that GALNT6 could be

another valuable marker to detect CTCs, since as few as 10 breast

cancer cells per ml blood sample were detectable with statistical

significance when compared to the reference sample.

In contrast, in the patient situation, the detection

of glycosyltransferase gene expression appears to be more

difficult. In some of the patient samples, expressions for the

selected genes were not detectable at all. In other cases, the

average gene values of the three most promising markers were

markedly higher in the 20 negative control samples, as compared to

the 20 adjuvant breast cancer samples. It may therefore be

concluded that results from the inoculation experiments should be

regarded with caution. The model system situation does not

necessarily allow conclusions to be drawn in a clinical

setting.

To overcome these limitations, a greater patient

collective should be analysed by quantitative PCR in order to

minimize statistical shortcomings due to low patient numbers.

Simultaneously, patient samples could be purified by the

CellSearch™ system, which is the only Food and Drug

Administration-approved method for CTC-detection from blood

samples. The benefit is that especially in the metastatic setting,

cleaner cell populations could be analysed and subsequently

compared to results of whole blood analysis. Since it is known that

the incidence for CTCs is much higher in metastatic patients, we

suspect that the establishment of a detection assay based on

quantitative PCR with GT markers could be much easier. However,

blood samples of metastatic breast cancer patients are more

difficult to obtain and thereby sample numbers are limited. Another

obstacle is, that a simultaneous CellSearch™ analysis to

quantitative PCR is relatively expensive. Importantly,

hematopoietic cells display at least a background expression of

glycosyltransferases, which emphasizes the role and importance of

adequate negative controls of healthy patients.

It could be of major importance to take into account

that multiple different subsets of breast cancers exist. In that

regard, it may be required to establish standards for each subset

(such as hormone-receptor positive, HER2neu overexpression, claudin

low, basal, luminal etc.) to balance out the possibility of

differential patterns of expression. A prior association between

different gradings cannot be ruled out.

Glycosyltransferases may not be the ideal marker

genes for quantitative PCR-based detection of CTCs from blood

samples of breast cancer patients. This may be due to environmental

influence, which can change rapidly according to different handling

techniques. Also, precise and careful handling of the primary

patient-derived blood samples is critical. Moreover, the monitoring

of gene expression of glycosyltransferases cannot be directly

associated to aberrant glycosylation and unfolding, as the temporal

order of events may differ. However, encouraging results in the

present study, especially in the presented model system, suggest

that a few select glycosyltransferases could be of use in certain

defined situations.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by a grant of the

Heuer-Stiftung Für Medizinische Forschung (grant no. 0012013). The

authors thank T. Thormeyer for help with statistical

evaluations.

References

|

1

|

Dennis JW, Granovsky M and Warren CE:

Glycoprotein glycosylation and cancer progression. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1473:21–34. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hakomori S: Aberrant glycosylation in

tumors and tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens. Adv Cancer Res.

52:257–331. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Varki A, Cummings R and Esko J:

Glycosylation Changes in Cancer. Essentials of Glycobiology. Varki

A: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1999

|

|

4

|

Cazet A, Julien S, Bobowski M, Burchell J

and Delannoy P: Tumour-associated carbohydrate antigens in breast

cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 12:2042010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Demetriou M, Nabi IR, Coppolino M, Dedhar

S and Dennis JW: Reduced contact-inhibition and substratum adhesion

in epithelial cells expressing GlcNAc-transferase V. J Cell Biol.

130:383–392. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Buckhaults P, Chen L, Fregien N and Pierce

M: Transcriptional regulation of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V

by the src oncogene. J Biol Chem. 272:19575–19581. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Le Marer N, Laudet V, Svensson EC, et al:

The c-Ha-ras oncogene induces increased expression of

beta-galactoside alpha-2, 6-sial-yltransferase in rat fibroblast

(FR3T3) cells. Glycobiology. 2:49–56. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hebbar M, Krzewinski-Recchi MA, Hornez L,

et al: Prognostic value of tumoral sialyltransferase expression and

circulating E-selectin concentrations in node-negative breast

cancer patients. Int J Biol Markers. 18:116–122. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Recchi MA, Hebbar M, Hornez L,

Harduin-Lepers A, Peyrat JP and Delannoy P: Multiplex reverse

transcription polymerase chain reaction assessment of

sialyltransferase expression in human breast cancer. Cancer Res.

58:4066–4070. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pantel K and Brakenhoff RH: Dissecting the

metastatic cascade. Nat Rev Cancer. 4:448–456. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ring A, Smith IE and Dowsett M:

Circulating tumour cells in breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 5:79–88.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Smerage JB and Hayes DF: The measurement

and therapeutic implications of circulating tumour cells in breast

cancer. Br J Cancer. 94:8–12. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lange T, Samatov TR, Tonevitsky AG and

Schumacher U: Importance of altered glycoprotein-bound N- and

O-glycans for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and adhesion of

cancer cells. Carbohydr Res. 389:39–45. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Park JH, Katagiri T, Chung S, Kijima K and

Nakamura Y: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 6

disrupts mammary acinar morphogenesis through O-glycosylation of

fibronectin. Neoplasia. 13:320–326. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fan TC, Li WD, Chang CH, et al: Role of

ST3Gal1 sialyltransferase in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res.

71:23052011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Julien S, Ivetic A, Grigoriadis A, et al:

Selectin ligand sialyl-Lewis x antigen drives metastasis of

hormone-dependent breast cancers. Cancer Res. 71:7683–7693. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Patani N, Jiang W and Mokbel K: Prognostic

utility of glycosyltransferase expression in breast cancer. Cancer

Genomics Proteomics. 5:333–340. 2008.

|

|

18

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bernard PS and Wittwer CT: Real-time PCR

technology for cancer diagnostics. Clin Chem. 48:1178–1185.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|