Introduction

The neuronal system is complex, and synaptic

contacts between polarized neurons are fundamental structures

(1,2). During the polarization process,

neurons extend several neurites, the majority of which develop into

dendrites and only one of which becomes an axon (3). Neurites are tipped with motile growth

cones that receive extracellular guidance cues to reach their

targets, thus forming neural circuits (4). Growth cones maintain the mobility

predominantly due to the rich and flexible cytoskeleton, which

contains microtubules and actin (5). Bundled microtubules are distributed

predominantly in the central (C-) domain of the growth cone, while

splayed or looped microtubules are predominantly in the peripheral

(P-) domain and the transitional (T-) zone (6). Actin expresses predominantly in the

P-domain and T-zone (7). When the

growth cone is in a quiescent state, the polymerization and

depolymerization of microtubules and actin exhibit a dynamic

balance (8). If the balance is

disrupted, the development of growth cone is affected.

Collapsin response mediator proteins (CRMPs),

consisting of five cytosolic proteins (CRMP 1–5), are highly

expressed in developing and adult nervous systems (9–11).

CRMPs were originally identified as downstream of the Semaphorin-3A

(Sema3A) signaling pathway (12).

CRMP-5, as the first identified CRMP-associated protein, has the

lowest homology with other CRMP proteins (13). CRMP-5 is highly expressed in

post-mitotic neural precursors and the fasciculi of fibers in

developing brains (14). Hotta

et al (15) observed that

CRMP-5 is able to regulate filopodia dynamics and growth cone

development, negatively responding to Sema3A signaling. Yamashita

et al (16) demonstrated

that CRMP-5 regulated dendritic development and synaptic plasticity

in the cerebellar Purkinje cells. However, conversely, CRMP-5 has

been reported to inhibit neurite outgrowth (17). In addition, CRMP-5 antagonized the

promoting effect of CRMP-2 on axonal and dendritic growth through a

tubulin-based mechanism (17).

Thus, the role of CRMP-5 in neurite outgrowth remains

controversial. In addition, CRMP-5 is able to interact with other

proteins during brain development, including tyrosine kinase

Fes/Fps (18) and the

mitochondrial protein septin (19), however the functional significance

of these interactions remains unclear. The distribution of CRMP-5

in the growth cones suggests its potential role in regulating

growth cone development and neurite outgrowth (15). However, the detailed mechanisms of

CRMP-5 interaction with actin remain to be fully elucidated.

The current study aimed to determine whether CRMP-5

would interact with the actin cytoskeleton network to dynamically

regulate the distribution and remodeling of cytoskeleton, thus to

mediate growth cone development and neurite outgrowth.

Materials and methods

Animals

The experiments were conducted on 1-day-old pups of

Sprague-Dawley rats (n=8–10). Rats were purchased from the

Institute of Laboratory Animal Science of Jinan University (Jinan,

China) and were sacrificed immediately. The rats were anesthetized

with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (30 mg/kg; Maijin

Biotechnology, Hubei, China). Normally, the rats were housed in a

temperature-controlled (20–22°C) room with a 12 h light/dark cycle,

and were provided with free access to food and water. All animal

procedures were performed in strict accordance with the

recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals from the National Institutes of Health (20). The protocol was approved by the

Jinan University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

(approval no. SCXK20110029; Guangzhou, China). All efforts were

made to minimize the suffering and number of animals used.

Cell culture and transfection

Hippocampi were dissected from the postnatal rat

pups (days 0–1), and dissociated hippocampal neurons were obtained

using 0.125% trypsin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.,

Waltham, MA, USA), which were plated at a density of

1×104 cells/cm2 onto poly-D-lysine

(PDL)-coated glass coverslips. Cultures were maintained in

Neurobasal-A (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) medium

containing 2% B27 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and 0.5 mM

glutamine (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) supplement at 37°C

in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Half of the culture

media was replaced every 3 days. Calcium phosphate (Promega

Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) transfections with different

constructs were conducted on 6–7 days in vitro (DIV), and

all experiments were performed on 7–8 DIV. Human embryonic kidney

(HEK)293 cell (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA)

culture was performed as described previously (21). To determine the expression of

Flag-CRMP-5, the constructed pCMV-CRMP-5-Tag2 (pCMV-Tag2 vector was

obtained from Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) was transfected into

HEK293 cells using calcium phosphate. To verify the efficacy and

specificity of siRNAs, co-transfection of 100 pmol siRNAs or NC

together with 2 µg of the pCMV-CRMP-5-Tag2 plasmids into

HEK293 cells was performed using calcium phosphate. Following

transfection, cells were grown for 36 h prior to harvesting.

Plasmids and siRNA fragments were transfected using the ProFection

Mammalian Transfection system (Promega Corporation), performed

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Growth cone particle isolation

The methods were performed according to previous

studies (22–24). Briefly, brains were dissected from

the rats at 18 days of gestation and homogenized by a Teflon-glass

homogenizer (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) in ~8 volumes

(w/v) of 0.32 M sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)

containing 1 mM MgC12 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mM Tes-NaOH

(Sigma-Aldrich; pH 7.3), and the following protease inhibitors: 3

µM aprotinin (Calbiochem; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA,

USA), 20 mM benzamidine, 1 mM leupeptin, 1 mM pepstatin A and 0.6

mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA). The homogenate was centrifuged at 200 × g for 15

min. The low speed supernatant was loaded onto a discontinuous

sucrose density gradient consisting of three layers: 0.75, 1.0 and

2.66 M; the gradients were spun to equilibrium at 150,000 × g for

200 min in a Beckman SW 40 Ti Rotor (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea,

CA, USA). The isolated growth cone gradients were prepared as

previously described (23).

Neuronal samples subjected to immunocytochemistry were scanned by

confocal microscopy. The fraction at the load/0.75 M interface

(designated A as in the referred reference) contained the isolated

growth cones or growth cone particles (GCPs). Then 'A' fraction

samples were subjected to electron microscopy (H-7650, Hitachi,

Tokyo, Japan).

Electron microscopic procedures were performed as

preciously described (23).

Briefly, aliquots were mixed slowly with increasing amounts of

phosphate-buffered glutaraldehyde (1.5%). After 10–15 min, the

fixed material was pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 5

min at room temperature into a conical embedding capsule (Electron

Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). After further

glutaraldehyde fixation and washing with arsenate buffer, samples

were treated with osmium tetroxide, block-stained with magnesium

uranyl acetate and embedded in embedding mixture from the Low

Viscosity Embedding Media Spurr's kit (all from Electron Microscopy

Sciences). Thin sections were cut, stained and examined with the

electron microscope.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as previously

described (24). Briefly, lysates

were separated using 8, 10 and 12% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) and were then electrophoretically

transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Membranes were blocked in

Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

with 5% milk and 0.05% Tween-20 and were then probed with the

following primary antibodies at 4°C overnight: Rabbit anti-CRMP-5

(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA, cat. no.

sc-292382; 1:1,000) and mouse anti-β-actin (cat. no. A5441;

Sigma-Aldrich; 1:1,000). Subsequent to washing with TBS + 0.05%

Tween; the membranes were incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (cat no. 115-001-008) or

anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (cat no. 711-001-003; Jackson

ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA; 1:5,000)

and were then visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation assays were performed as

described previously (21,25). For immunoprecipitation of

hippocampal neurons, extracts were prepared by solubilization in

400 µl of cell lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 10 min at 4°C. Subsequent to brief sonication,

the lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min

at 4°C, the cell extract was then immunoprecipitated with 4

µg of the antibodies against CRMP-5 (1:500) or β-actin

(1:1,000), then the samples were incubated with 60 µl of

protein G plus protein A-agarose (Calbiochem; EMD Millipore) for 16

h at 4°C by continuous inversion. Immunocomplexes were pelleted at

500 × g for 5 min at 4°C and washed three times. The precipitated

immunocomplexes were boiled in Laemmli buffer and assayed using

western blot analysis with anti-CRMP-5 or mouse monoclonal

anti-β-tubulin antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich; cat. no. T5201; dilution,

1:2,000).

Immunofluorescence

Hippocampal neurons were grown on coverslips (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and were processed for immunofluorescence

according to the standard protocol described previously (24). Cells were fixed with 4% (w/v)

paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature and

permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS) for 20 min. The cells were blocked in 3% normal donkey serum

(Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc.) in TBS + 0.1% Triton

X-100 for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the rabbit

anti-CRMP-5 and mouse anti-actin antibodies at 4°C overnight. The

cells were washed 3 times for 10 min with PBS + 0.1% Tween-20, and

were incubated with the monoclonal donkey anti-rabbit IgG Dylight

549 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.; cat. no.

711-516-152; 1:1,000) or monoclonal donkey anti-mouse IgG Dylight

488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.; cat. no.

715-485-150; 1:1,000) for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequent to

three washes in lysis buffer, cells were mounted on glass slides

with Fluoro Gel II containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

(Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). For

co-localization analysis, confocal images were analyzed using

ImageJ software (version 1.48, National Institutes of Health,

Bethesda, MA, USA) with Just Another Colocalization Plugin (JACoP,

National Institutes of Health) (26). The random or codependent nature of

colocalizations were tested using Cytofluorogram and intensity

correlation analysis. All the co-localization calculations were

performed on >10 cells from at least three independent

experiments. Microscopy and image analysis were conducted using the

same optical slice thickness for every channel using a confocal

microscope (LSM 710; Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

RNA interference

A validated CRMP-5 short interfering RNA (siRNA)

(siCRMP-5) fragment and NC (scrambled sequence, negative control)

were synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China)

and validated previously (15,17,24).

Hippocampal neurons were transfected with siRNA using a calcium

phosphate protocol (27). To

transfect neurons in 24-well tissue culture plates, 100 pmol siRNA

was combined with 37 µl 2 M CaCl2 solution in

sterile, deionized water to a final volume of 300 µl and

then mixed well with 300 µl 2X

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid-buffered saline.

The mixtures were vortexed and incubated at 25°C for approximately

4 min. In each well, 30 µl mixture was added drop-wise to

the cells and allowed to incubate for an additional 25 min. The

green fluorescent protein expression plasmid (Addgene) was

co-transfected with the siRNAs to mark the transfected cells.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Significant differences were assessed with one-way analysis of

variance followed by the Bonferroni or Tamhane post hoc tests.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

CRMP-5 interacts with cytoskeleton

In order to separate GCPs from the soma, sucrose

gradient centrifugation was used. GCPs were then subjected to

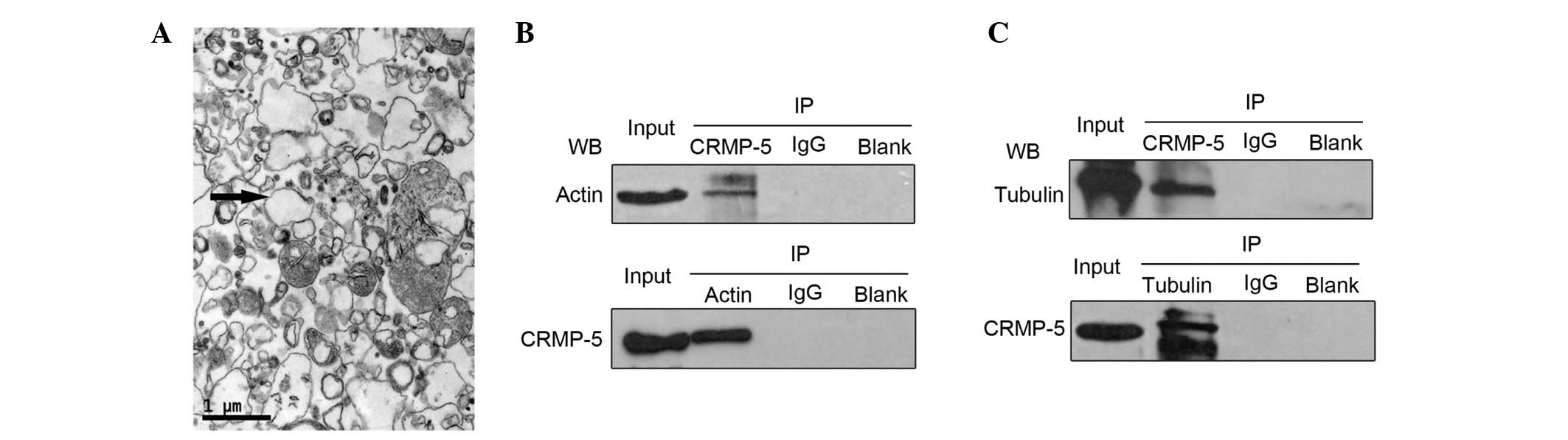

transmission electron microscopy. As presented in Fig. 1A, GCPs existed as vesicular

structures (indicated by arrows), with a uniform size (~1

µm) and loose distribution, which was consistent with

previously reported results (22).

Subsequently, co-immunoprecipitation was conducted in order to

determine whether CRMP-5 would interact with the actin and tubulin

cytoskeletons, rather than with tubulin alone as previously

reported (24). Using the CRMP-5

antibody, the actin immune-signal in the CRMP-5-precipitated

sediment from GCP lysates was detected, with no actin immune-signal

in the IgG and blank control groups (Fig. 1B, upper panel). Conversely, using

the actin antibody, a CRMP-5 signal was detected in the

actin-precipitated sediment (Fig.

1B, lower panel). Furthermore, CRMP-5 was indicated to interact

with tubulin using the CRMP-5 and tubulin antibodies (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that CRMP-5

interacts with the actin and tubulin cytoskeleton systems.

CRMP-5 colocalizes with actin in growth

cones of hippocampal neurons

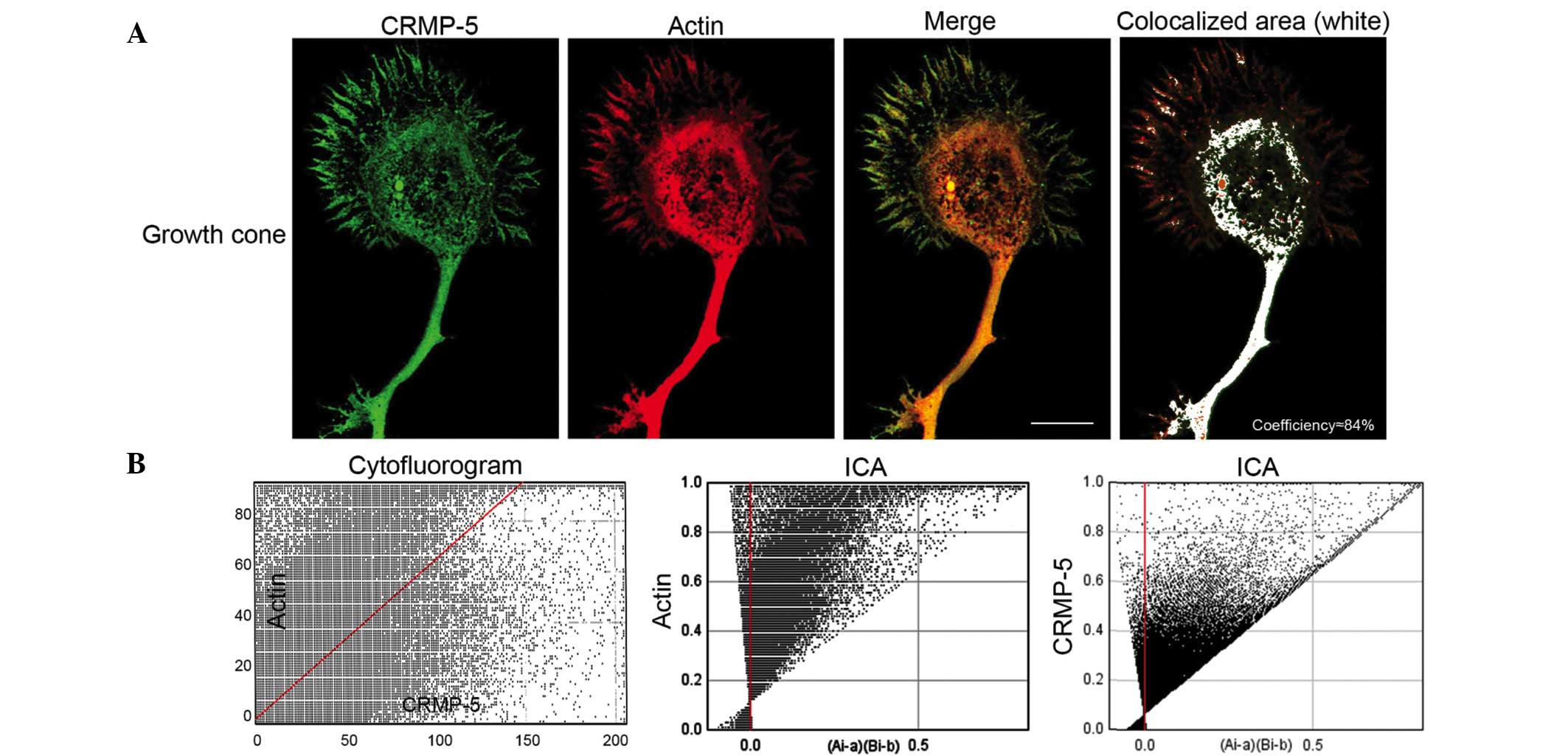

Furthermore, the distribution of actin and CRMP-5 in

growth cones of developing hippocampal neurons was investigated.

Neurons were cultured at a density of 1×104

cells/cm2 on a PDL-coated coverslip. At 3 DIV, neurons

were subjected to immunofluorescence with CRMP-5 and actin

antibodies. As presented in Fig.

2, actin was predominantly distributed in the P-domain and

T-zone, with fewer signals in the C-domain. Lamellipodia in the

P-domain exhibited a clear mesh and bundled filaments. CRMP-5 was

distributed predominantly in the C-domain and T-zone, however also

exhibited clear signals in the lamellipodia and filopodia of the

P-domain. CRMP-5 and actin were observed to exhibit colocalization

in the actin filaments in the P-domain and in the T-zone, with a

colocalization co-efficiency of 84% (Fig. 2, right panel). Using analysis with

ImageJ plus JACoP (26), a clear

cytofluorogram and ICA score between actin and CRMP-5 was obtained,

which additionally indicted colocalization of actin and CRMP-5.

These data suggest that CRMP-5 colocalizes with actin in the growth

cones of developing neurons.

CRMP-5 regulates actin dynamics and

growth cone development

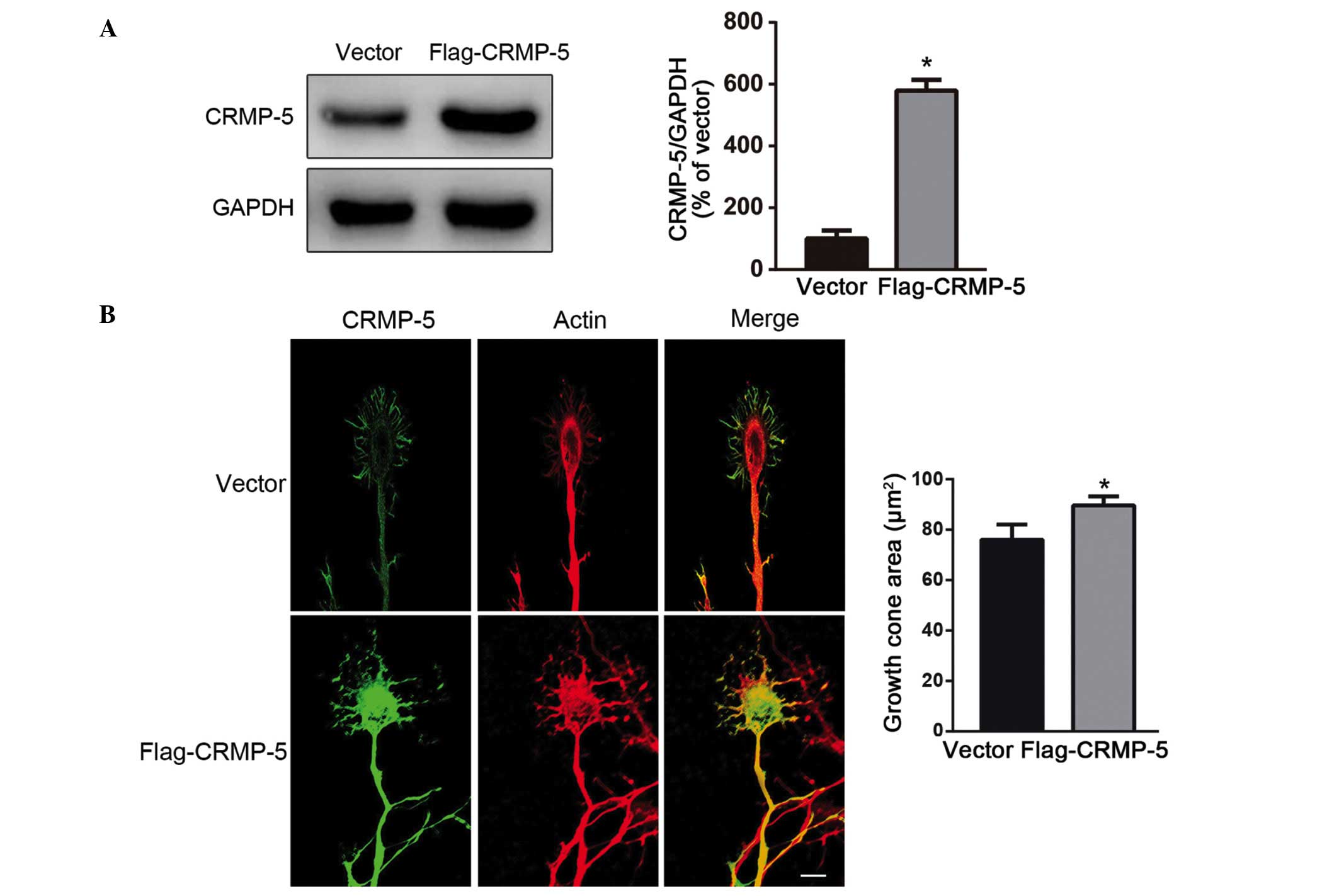

In order to determine the effect of CRMP-5 on actin

dynamics and growth cone development, a CRMP-5 expression plasmid

(pCMV-CRMP-5-Tag2) was constructed, which had been previously

reported (26). As presented in

Fig. 3A, the CRMP-5 plasmid was

successfully expressed in HEK293 cells by the detection of western

blot with the Flag antibody. The plasmid was then transfected into

hippocampal neurons. As presented in Fig. 3B, growth cones transfected with

CRMP-5 were fan-shaped, with actin predominantly distributed in the

P-domain with long actin filaments and increased branches.

Overexpression of CRMP-5 promoted growth cone development, with an

enlarged growth cone area (Fig.

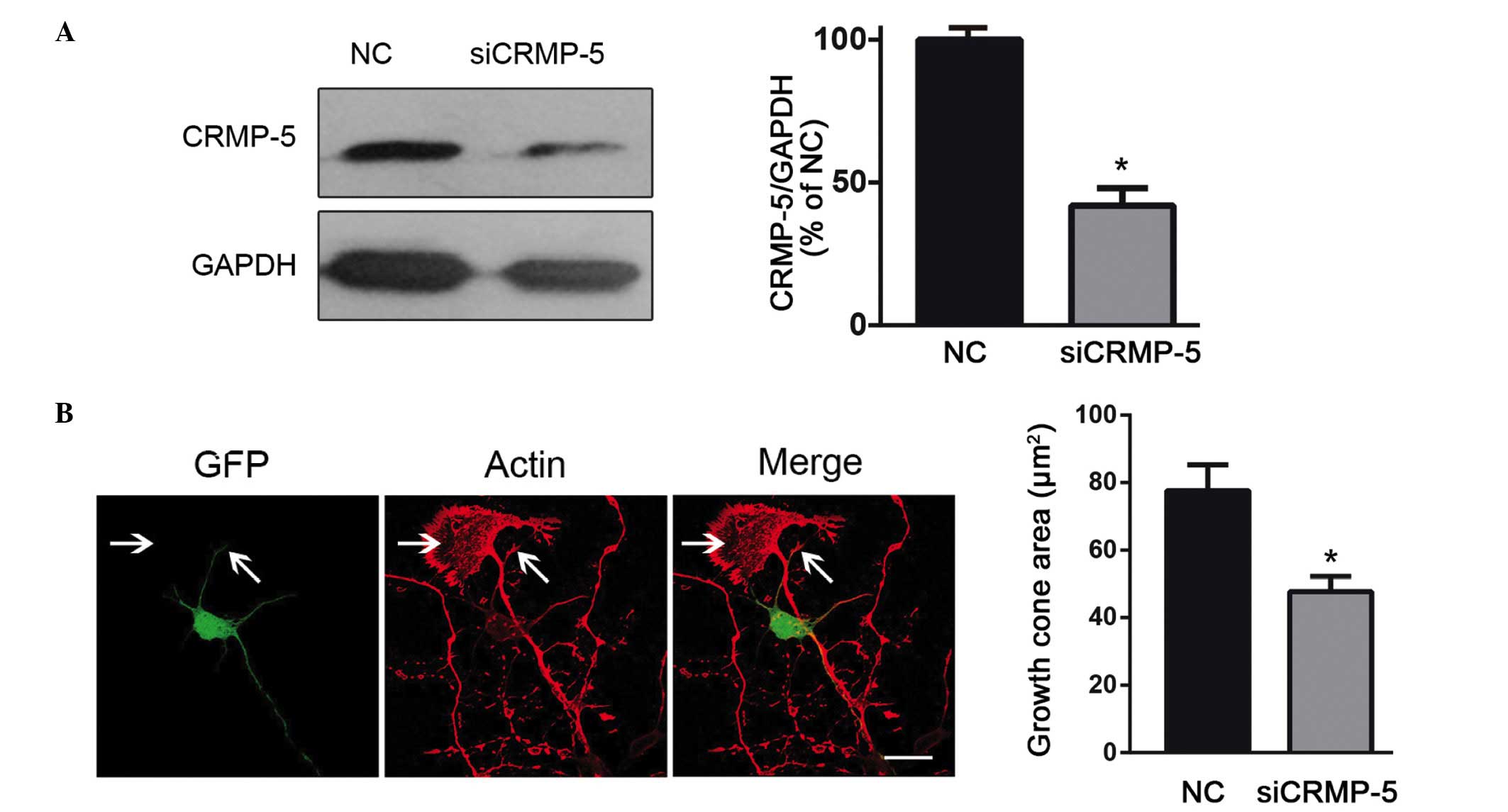

3B, right panel). The CRMP-5 siRNA experiment was then

conducted, where the siRNA efficiency was determined previously

(24) and the results are

presented in Fig. 4A. On CRMP-5

silencing, the actin filaments were observed to become fragile, and

exhibited collapsed growth cones, compared with those in

non-transfected neurons (Fig. 4B).

These data suggest that CRMP-5 regulates actin dynamics and growth

cone development.

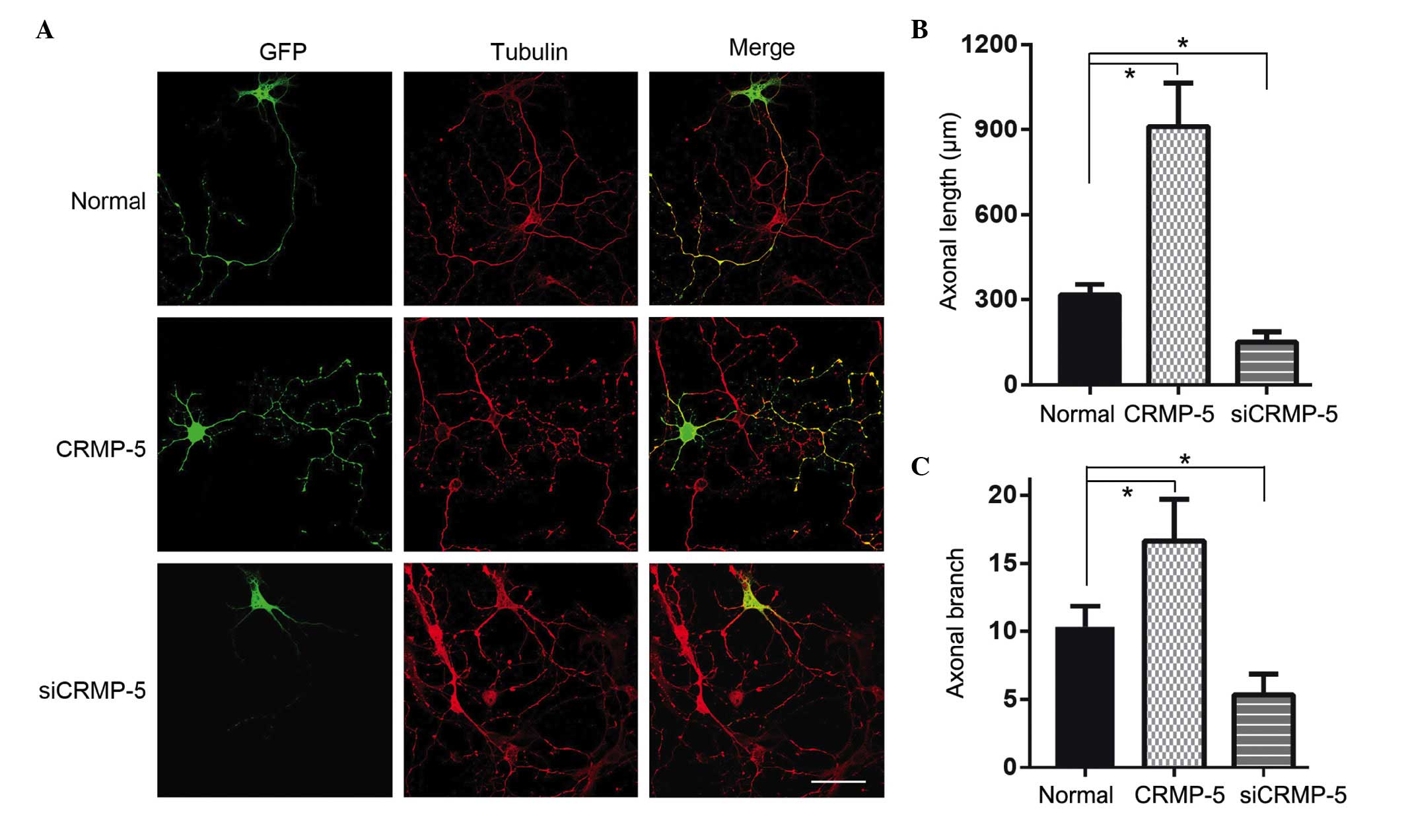

CRMP-5 regulates neurite outgrowth

It was then investigated whether CRMP-5 would

regulate neurite outgrowth. Hippocampal neurons were transfected

with the CRMP-5 overexpression plasmid or with CRMP-5 siRNA

fragments. Subsequent to transfection for 5 days, the neurons were

subjected to immunocytochemistry. As presented in Fig. 5, the CRMP-5-overexpressing neurons

were observed to have a longer neurite length and an increased

number of neurite branches than that of CRMP-5-silenced neurons,

which possessed short neurite length and few branches (Fig. 5B and C). These data suggest that

CRMP-5 regulates neurite outgrowth via modulating actin dynamics

and growth cone development.

Discussion

CRMPs are critical for growth cone development,

axonal guidance and neuronal polarity. CRMP proteins 1–5 have been

implicated to associated with tubulin (17,28).

CRMP-5, an isoform distinct from the other four CRMPs, was recently

reported to localize in the filopodia of growth cones (15), leaving the role of

CRMP-5-associated proteins in regulating growth cones to be further

elucidated. Thus, in the current study, it was identified that

CRMP-5 interacted with the actin cytoskeleton, colocalized with

actin in growth cones, regulated actin dynamics and modulated

growth cone development and neurite outgrowth.

Neurite outgrowth relies on the interaction between

the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton (29). Actin and microtubules within the

growth cone are not independent, however are associated, sensing

each other's movement (29).

Heidemann et al (30)

identified that coordinated cytoskeletal movement was important in

axon guidance. Numerous signaling transduction pathways and

proteins have been reported to be involved in this process. These

proteins include Rho family proteins (31–33),

plus-end tracking proteins (34,35),

spectraplakins (36,37) and microtubule-associated proteins

(38), particularly tau protein

(39–41). In addition, CRMPs may be the

structural mediator of actin and microtubules, CRMP-2 is able to

interact with tubulin promoting its assembly (28,42).

CRMP-4 interacts with actin and promotes neurite growth (43,44).

Previous studies have identified that CRMP-5 interacts with tubulin

in the growth cones (24). It has

additionally been identified that CRMP-2 and CRMP-4 interact to

coordinate cytoskeletal dynamics, regulating growth cone

development and axon elongation (45). Whether additional novel proteins or

members of the CRMP family, (e.g. CRMP-1 and CRMP-3) are involved

in this process remains unclear, thus requires further

investigation.

CRMP-5 is highly distributed in fetal and neonatal

rat brains and is markedly reduced in adult brains (13). In hippocampal neurons, the

spatiotemporal distribution of CRMP-5 varies at different

developmental stages; CRMP-5 is present in growth cones at stage 3

when neuronal polarity is developed, and reduces to a low level

when neurons are polarized. Thus, CRMP-5 contributes to the dynamic

regulation of neuronal polarity (17). The data of the current study are

consistent with previously reported data (15), in that CRMP-5 in the growth cone is

necessary and sufficient for growth cone development. The results

of the current study additionally suggest that CRMP-5 functions

through its interaction with the cytoskeleton. CRMP-5 has been

reported to inhibit dendritic growth in hippocampal neurons

(17). However, in cerebellar

Purkinje cells, CRMP-5 has been previously reported to promote

dendritic development and synaptic plasticity in studies using

CRMP-5−/− mice, where aberrant dendrite morphology was

observed (16,17). The different functions of CRMP-5

from these studies suggest that CRMP-5 acts to be cell-type

specific and this may be due to its efferent distribution or its

different interacting proteins. Taken together, the current study

has provided novel evidence for CRMP-5-regulated growth cone

development and neurite outgrowth.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31170941 and

31300885), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province,

China (grant nos. S2013010014191, 2014A030310024 and

2014A030313357), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of

Guangdong Province, China (grant nos. A2014382 and A2015479) and

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant

no. 21615477).

Abbreviations:

|

CRMP

|

collapsin response mediator

protein

|

|

MTs

|

microtubules

|

|

DIV

|

days in vitro

|

|

NC

|

negative control

|

|

T-zone

|

the transition zone

|

|

C-domain

|

the central domain

|

References

|

1

|

Huber AB, Kolodkin AL, Ginty DD and

Cloutier JF: Signaling at the growth cone: Ligand-receptor

complexes and the control of axon growth and guidance. Annu Rev

Neurosci. 26:509–563. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tessier-Lavigne M and Goodman CS: The

molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 274:1123–1133. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rolls MM and Jegla TJ: Neuronal polarity:

an evolutionary perspective. J Exp Biol. 218:572–580. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nieto MA: Molecular biology of axon

guidance. Neuron. 17:1039–1048. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zou Y: Does planar cell polarity signaling

steer growth cones? Curr Top Dev Biol. 101:141–160. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pak CW, Flynn KC and Bamburg JR:

Actin-binding proteins take the reins in growth cones. Nat Rev

Neurosci. 9:136–147. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Schaefer AW, Kabir N and Forscher P:

Filopodia and actin arcs guide the assembly and transport of two

populations of micro-tubules with unique dynamic parameters in

neuronal growth cones. J Cell Biol. 158:139–152. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Buck KB and Zheng JQ: Growth cone turning

induced by direct local modification of microtubule dynamics. J

Neurosci. 22:9358–9367. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Minturn JE, Fryer HJ, Geschwind DH and

Hockfield S: TOAD-64, a gene expressed early in neuronal

differentiation in the rat, is related to unc-33, a C. elegans gene

involved in axon outgrowth. J Neurosci. 15:6757–6766.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fukada M, Watakabe I, Yuasa-Kawada J,

Kawachi H, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y and Noda M: Molecular

characterization of CRMP5, a novel member of the collapsin response

mediator protein family. J Biol Chem. 275:37957–37965. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yuasa-Kawada J, Suzuki R, Kano F, Ohkawara

T, Murata M and Noda M: Axonal morphogenesis controlled by

antagonistic roles of two CRMP subtypes in microtubule

organization. Eur J Neurosci. 17:2329–2343. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Goshima Y, Nakamura F, Strittmatter P and

Strittmatter SM: Collapsin-induced growth cone collapse mediated by

an intracellular protein related to UNC-33. Nature. 376:509–514.

1995. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Inatome R, Tsujimura T, Hitomi T, Mitsui

N, Hermann P, Kuroda S, Yamamura H and Yanagi S: Identification of

CRAM, a novel unc-33 gene family protein that associates with CRMP3

and protein-tyrosine kinase(s) in the developing rat brain. J Biol

Chem. 275:27291–27302. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ricard D, Rogemond V, Charrier E, Aguera

M, Bagnard D, Belin MF, Thomasset N and Honnorat J: Isolation and

expression pattern of human Unc-33-like phosphoprotein 6/collapsin

response mediator protein 5 (Ulip6/CRMP5): Coexistence with

Ulip2/CRMP2 in Sema3a- sensitive oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci.

21:7203–7214. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hotta A, Inatome R, Yuasa-Kawada J, Qin Q,

Yamamura H and Yanagi S: Critical role of collapsin response

mediator protein-associated molecule CRAM for filopodia and growth

cone development in neurons. Molecular Biology of the Cell.

16:32–39. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Yamashita N, Mosinger B, Roy A, Miyazaki

M, Ugajin K, Nakamura F, Sasaki Y, Yamaguchi K, Kolattukudy P and

Goshima Y: CRMP5 (collapsin response mediator protein 5) regulates

dendritic development and synaptic plasticity in the cerebellar

Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 31:1773–1779. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Brot S, Rogemond V, Perrot V,

Chounlamountri N, Auger C, Honnorat J and Moradi-Améli M: CRMP5

interacts with tubulin to inhibit neurite outgrowth, thereby

modulating the function of CRMP2. J Neurosci. 30:10639–10654. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mitsui N, Inatome R, Takahashi S, Goshima

Y, Yamamura H and Yanagi S: Involvement of Fes/Fps tyrosine kinase

in sema-phorin3A signaling. EMBO J. 21:3274–3285. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

National Research Council: Guide for the

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press;

Washington DC: 1996, pp. 125

|

|

20

|

Takahashi S, Inatome R, Yamamura H and

Yanagi S: Isolation and expression of a novel mitochondrial septin

that interacts with CRMP/CRAM in the developing neurones. Genes

Cells. 8:81–93. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang J, Fan J, Tian Q, Song Z, Zhang JF

and Chen Y: Characterization of two distinct modes of endophilin in

clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Cell Signal. 24:2043–2050. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pfenninger KH, Ellis L, Johnson MP,

Friedman LB and Somlo S: Nerve growth cones isolated from fetal rat

brain: Subcellular fractionation and characterization. Cell.

35:573–584. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lohse K, Helmke SM, Wood MR, Quiroga S, de

la Houssaye BA, Miller VE, Negre-Aminou P and Pfenninger KH: Axonal

origin and purity of growth cones isolated from fetal rat brain.

Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 96:83–96. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xiao L, Liu W, Li J, Xie Y, He M, Fu J,

Jin W and Shao C: Irradiated U937 cells trigger inflammatory

bystander responses in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

through the p38 pathway. Radiat Res. 182:111–121. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tian Q, Zhang JF, Fan J, Song Z and Chen

Y: Endophilin isoforms have distinct characteristics in

interactions with N-type Ca2+ channels and dynamin I. Neurosci

Bull. 28:483–492. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bolte S and Cordelières FP: A guided tour

into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J

Microsc. 224:213–232. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tan M, Ma S, Huang Q, Hu K, Song B and Li

M: GSK-3α/β-mediated phosphorylation of CRMP-2 regulates

activity-dependent dendritic growth. J Neurochem. 125:685–697.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fukata Y, Itoh TJ, Kimura T, Ménager C,

Nishimura T, Shiromizu T, Watanabe H, Inagaki N, Iwamatsu A, Hotani

H and Kaibuchi K: CRMP-2 binds to tubulin heterodimers to promote

microtubule assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 4:583–591. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Dent EW, Gupton SL and Gertler FB: The

growth cone cytoskeleton in axon outgrowth and guidance. Cold

Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3:a0018002011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Heidemann SR, Landers JM and Hamborg MA:

Polarity orientation of axonal microtubules. J Cell Biol.

91:661–665. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ren XD, Kiosses WB and Schwartz MA:

Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion

and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 18:578–585. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Waterman-Storer CM, Worthylake RA, Liu BP,

Burridge K and Salmon ED: Microtubule growth activates Rac1 to

promote lamellipodial protrusion in fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol.

1:45–50. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Watabe-Uchida M, Govek EE and Van Aelst L:

Regulators of Rho GTPases in neuronal development. J Neurosci.

26:10633–10635. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Watanabe T, Noritake J and Kaibuchi K:

Roles of IQGAP1 in cell polarization and migration. Novartis Found

Symp. 269:92–101; discussion 101–105, 223–230. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Komarova Y, Lansbergen G, Galjart N,

Grosveld F, Borisy GG and Akhmanova A: EB1 and EB3 control CLIP

dissociation from the ends of growing microtubules. Mol Biol Cell.

16:5334–5345. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Suozzi KC, Wu X and Fuchs E:

Spectraplakins: Master orchestrators of cytoskeletal dynamics. J

Cell Biol. 197:465–475. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kodama A, Lechler T and Fuchs E:

Coordinating cytoskeletal tracks to polarize cellular movements. J

Cell Biol. 167:203–207. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cueille N, Blanc CT, Popa-Nita S, Kasas S,

Catsicas S, Dietler G and Riederer BM: Characterization of MAP1B

heavy chain interaction with actin. Brain Res Bull. 71:610–618.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

He HJ, Wang XS, Pan R, Wang DL, Liu MN and

He RQ: The proline-rich domain of tau plays a role in interactions

with actin. BMC Cell Biol. 10:812009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Correas I, Padilla R and Avila J: The

tubulin-binding sequence of brain microtubule-associated proteins,

tau and MAP-2, is also involved in actin binding. Biochem J.

269:61–64. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Henríquez JP, Cross D, Vial C and Maccioni

RB: Subpopulations of tau interact with microtubules and actin

filaments in various cell types. Cell Biochem Funct. 13:239–250.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Arimura N, Menager C, Fukata Y and

Kaibuchi K: Role of CRMP-2 in neuronal polarity. J Neurobiol.

58:34–47. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Rosslenbroich V, Dai L, Baader SL, Noegel

AA, Gieselmann V and Kappler J: Collapsin response mediator

protein-4 regulates F-actin bundling. Exp Cell Res. 310:434–444.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Quinn CC, Chen E, Kinjo TG, Kelly G, Bell

AW, Elliott RC, McPherson PS and Hockfield S: TUC-4b, a novel TUC

family variant, regulates neurite outgrowth and associates with

vesicles in the growth cone. J Neurosci. 23:2815–2823.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tan M, Cha C, Ye Y, Zhang J, Li S, Wu F,

Gong S and Guo G: CRMP4 and CRMP2 interact to coordinate

cytoskeleton dynamics, regulating growth cone development and axon

elongation. Neural Plast. 2015:9474232015.PubMed/NCBI

|